Sarah McCarry's Blog, page 11

March 25, 2013

Trigger Warning

When I interview writers for my blog I often look up reviews of their books; a little bit research, a little bit procrastination. Even the work I like to do I like to put off. I am, in fact, putting off work right now. But it's nice to see, often, the kinds of questions other people are thinking about. Erica Lorraine Scheidt's book Uses for Boys is a book that is painful to read in places; its narrator, Anna, has sex in order to find out who she is and what her value is in relation to other people. The adults in her world do not take care of her or look out for her. She is sexually assaulted on a school bus; she is raped at a party; she has sex that is loving and not loving with people she does and does not care about. She is, you know, human. When I looked up the book before I interviewed Erica, I was not surprised to see that many, many reviews took issue not with the writing or the story or the structure, but with the main character's sexuality; but even I was startled by the vitriol of many of them, the insistence that a story about a girl who fucks cannot be a story with any value at all. That a girl who fucks cannot have any value at all. I read them all, one after the other, and I could feel them in my stomach, gathering weight. "Anna is probably not a likable character. This is because of her choices and because they don't make a lot of sense." "Bad things happen to Anna and Anna does bad things in turn. Do you think Anna feels bad for any of it? No, she doesn't." "Anna sort of made these decisions herself spur of the moment not taking into consideration, the repercussions after, so you can see why I had no sympathy for her."

Today is grey and cold and, unseasonably, snowing, and I am sadder than I ought to be about various things of no consequence. I have had some version of this piece sitting on my desktop for months. I hover the mouse over the "publish" button and then I move it away again. I wanted to tell you about something else instead, like how last night I told my friend over the phone that you can never admit in public that you find Infinite Jest boring, because people just think you are too stupid to get it, and then this afternoon on the train I saw a man who looked exactly like David Foster Wallace, and it seemed like a sign, but of what I don't know. I don't want to write about rape anymore. But here we are.

"My biggest misunderstanding was in that the blame seemed to be placed more on the boys and less on Anna making poor decisions and her mother’s inability to lovingly care for her daughter." "I kept expecting her to eventually make better choices or at least learn from her mistakes. But hello, who gets raped and doesn't even realize I mean not fully."

I was mercifully unaware of what had happened in Steubenville until relatively recently, when, in a tire store of all places, the story came on the news while I was waiting with a friend for his car tires to get changed. Without warning, the YouTube video was on the television screen. I went into the bathroom and threw up. When I came out of the bathroom the story was still on and so I went into the bathroom again and locked myself in the stall and cried--this is what I do, I guess, go into bathroom stalls and cry--and the image of that girl's body, swinging between two boys, their faces blurred, is one that I can still see, even now, three months later. The knowledge of not just what was done, but of how many people watched.

"I also wasn't a fan of how Anna's promiscuity started. Anna had a choice from the moment she was on the bus to make very different decisions than she did."

Slutty, unlikable, passive, drunk, poor decisions, doesn't make a lot of sense, dirty, has too much sex, has sex, is probably thinking about sex, poor, brown, wrong body, wrong gender, at the wrong party, didn't say the right kind of no, couldn't say no, didn't know how to try. What are we talking about, here? A book? A girl? A human body? One another? Me? It gets harder and harder to tell.

"Here's the part that really made me wanna smack the girl. Anna goes out to a party, gets drunk, and this post-high school guy spends the night pinching and twisting at her nipples. She doesn't want him to, but hey, it seems to be a normal occurrence for her, so the most she does is flick him off for doing it. So it's no wonder the guy finds her drunk @ss later to rape her. He pins her down and covers her mouth, and when he's done, casually asks her not to say anything to anyone. 'Okay,' is her reaction."

There is more than one way to survive.

"I didn't like her at ALL. I kinda want to punch her in the face. I don't really want to go slut-shaming and all that. But seriously."

If language wounds so well there is hope in the thought that it can also bring us together, mark us out as warriors, as kin. That we can build bridges out of our scars.

"I'm sorry, but this girl truly is a slut with major mental issues, with no one to blame but herself."

I want to write the thing that will make it all make sense because I don't fucking want to write about this anymore. I don't fucking want to think about it anymore. Do you understand? Walking through the park a few nights ago, not that late. I have an old, bad back injury; every now and then, the muscles seize up, and I walk with a noticeable limp. Past a group of men. The algebra you do: how many of them there are factored by do they mean me harm times how fast can I run. "Why's she walking like that?" one of them said to the others. "Sweetheart, you hurt? You want me to help you?" My heart stopped. I'm sure he meant well. In the wild, a wounded animal is often left to die. Last night watching an old episode of Buffy. Some cheesy biker demons rampage across the town. They corner all of Buffy's most annoying friends. "Some of us have anatomical peculiarities," sneers a demon to Buffy's witchy bestie. "They tend to tear up little girls." Well, I tell you what. Picturing that really fucked me up for a while.

"I honestly and truly believe that Anna had something wrong with her."

I chose not to link directly to any of the reviews; I have no interest in summoning the short-lived internet vengeance machine. They're real. You can find them for yourself, if citations are important to you. I will tell you that every single one of them quoted here, except for one, was written by a woman.

"Had the author just given me that last scene where she proved that Anna was going to become something better than she was, I could've give this novel at least three stars. Now... I hate even giving it one. It disturbs me that much that this girl slutted around, got high, got drunk, and didn't change anything about herself moving forward."

I didn't change anything about myself, moving forward. "Okay" was my reaction, too. This body, this heart, the same old fucking stories. I still drink too much sometimes and sometimes I don't. I went to a lot of the wrong parties. I tattoo my own history on my skin but I'm starting to forget it anyway. Am I becoming something better than what I was? Should I be?

I don't know. You tell me.

March 19, 2013

Why Don't You Buy Some Things

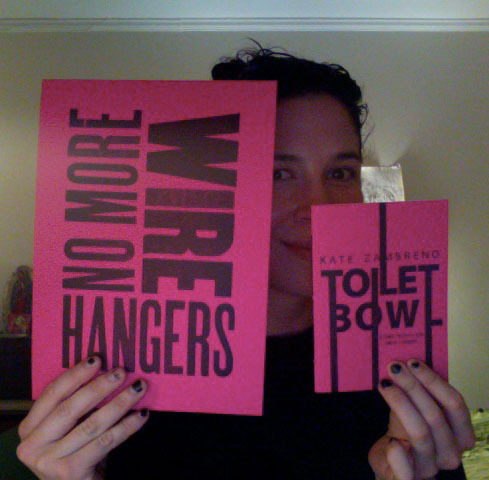

Here is Kate Zambreno's chapbook, all finished, and ready for you to order it, and here is also the limited-edition letterpress poster that comes with the special edition, which you may order as well. I am displaying these items for you whilst garbed in the Sisters of Mercy shirt I just scored off ebay for thirty dollars, which came to me direct from the basement of a friendly goth and reeked so badly of cigarettes that I have spent today attempting to fumigate it with a variety of hippie oils, biodegradable detergents, and Nag Champa, with the unfortunate result that now it just smells like someone died at a Grateful Dead concert. You see that I am wearing it anyway! So if you run into me, and I am wearing this shirt, you might be advised to keep your distance. I am relating this anecdote in case you had said to yourself recently, "I wonder if Sarah McCarry never posts anymore because she has turned into an adult." Another thing I had a hand in making is this book, which you can preorder, if you are so inclined, from the very very wonderful people at Word bookstore in Brooklyn, and it will come to you in July, signed by me, wherever you are in the world. I remain very fond of all of you.

March 4, 2013

A Conversation with Kat Howard

Kat Howard's short fiction has been performed on NPR as part of Selected Shorts. She has recently been published in the anthology Oz Reimagined, edited by John Joseph Adams and Douglas Cohen, and in Apex and Subterranean magazines. A recovering academic, she now lives and writes in the Twin Cities. And in a rather startling coincidence, she and I found out recently that we both went to the same high school outside of Seattle. The world is both fantastical and tiny. You can read her short fiction online at Subterranean, Apex, and Lightspeed, among other places.

We were both raised Catholic, and we both ended up writing stories of complicated girls wandering dark paths through the fantastical. Are those two things connected at all for you? How did the mythology of the church affect the mythology of your fiction?So, I'm going to answer the second half first, because that's a lot clearer for me. First, I'm so glad you used the word "mythology." I feel like the Christian mythos gets segregated from the other large mythic cycles in a way that can be really poisonous, and that prevents people from engaging with it as Story. Like, I have so many issues with Milton, but I would love to see someone take on a project like Paradise Lost, and I fear that wouldn't happen because of the idea that Christian mythology is so extra-special that we can't touch it in fiction. Which is ridiculous.Sorry. Back on point.I grew up on the stories of the saints, and honestly, those things can be batshit. Saint Christopher, who is invoked against werewolves, and has the head of a dog! Christina the Astonishing, who likes to pop in and out of people's ovens for fun! I mean, if you want to write speculative fiction at all, read Jacob Voragine's The Golden Legend, which is a collection of saints' lives. It will set you right up.But behind the sort of delightful oddity (and sometimes wonder, sheer, actual numinous wonder) of the saints' lives, there was also the serious problem of the treatment of women in them. If you were a woman, you became a saint by being a virgin, or a martyr, and you were quite often martyred in preservation of virginity. Being a Catholic girl who becomes a saint is worse than being the girl who has sex in the horror movie and then dies first--if you decide you don't want to have sex, you'll be horribly martyred, and then spend eternity being depicted holding your severed breasts on a plate. Ungood.So for me, one of the big things that is (to the extent that a person can know this about her own fiction) a part of my writing, is that tension between the desire for the numinous, and dealing with that institutionalized dark path, the one that says men can be saints for thinking deeply about faith, and for fighting for it, but you, well, you're a virgin, or you're dead, and often both. I feel like Joan of Arc haunts a lot of the women that I write, and I'm happy to have her do so.But at the same time as I say, yes, Christian mythology is a mythos that should be open for writers to work in, it's often not the one I'm interested in working directly with in my writing. I mean, if I'm going to send a girl to Hell, I'm not going to send her to the Christian Hell, I'm going to send her to Hades, and tell her not to look back when she leaves.Which I think is a preoccupation we both share, so I am very interested to hear your take on this.I'm very partial to Hades myself, as you know. And for me, too, those mythologies are what most intrigue me as a writer: Persephone, Eurydice, Medea. The lives of the lady saints are not especially appealing narratives for me; I want the women who are stabbing their husbands in the bathtub and sleeping with their stepsons and turning their romantic rivals into cows.But Catholic mythology specifically is so delicious to me--there is obviously a history of real-life horror and genocide and Inquisition, which I do not mean at all to overlook, but there's also centuries of, as you said, batshit political intrigue and puppet kings and competing popes and corruption and thrilling scandal. And what is really a belief in magic, a very pagan sort of magic, and fascination with ritual. I'm reading Victoria Nelson's book Gothicka right now, which is a fabulous study of permutations of the Gothic, and she points out that even in very Protestant America, if you want an exorcism or the removal of a displeasing vampire, you don't call a Methodist, you call a Catholic priest. (She quotes Elizabeth Kostova: "The hospitable plain Protestant chapels that dotted the university... didn't look qualified to wrestle with the undead.")So if anything, growing up Catholic raised me to believe in magic, which I am sure was not the intent of my Sunday school teachers. What about you? How did you get from the Christian hell to the much older one? Gothicka looks kind of amazing. [It is. --ed.] I must add that to my reading list.Your comment about growing up Catholic raising you to believe in magic, but that not being the intent of your Sunday school teachers really struck a chord with me, because it is the ritual, and the magic, and the strangeness of the Church where I find myself most comfortable (I wrote my dissertation on the writings of women mystics). For me, anyway, that magic, that sense of this is an extranormal thing, is the attraction of a belief in a life outside of the mundane. At the same time, I feel that it's a thing the Church has always struggled with addressing, the people whose spirituality involves extraordinary expressions, ecstasies and voices, the medieval people who would run from church to church, so as to witness the consecration over and over again, much to the grumpiness of the local hierarchy. I don't go to mass often anymore (see: the current real-life horror going on in the organized Church), but when I do go, I look for a place where I can maximize my exposure to the formal rituals that invest the event with that feeling of, well, magic. I want to feel that I am participating in an event that is ancient, that has a couple of thousand years of meaning built into it.The switch from the sort of literary fascination with a Christian mythos to a broader one came about pretty early for me. It was, of course, the fault of books. One of which was The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. I read it for the first time when I was seven, and even then, I got the whole, "Aslan is Jesus" thing. Being Catholic, I didn't really see the problem with that then. But what I did see was that Narnia had a ton of other cool things in - nymphs and dryads and dragons and all of that. I've always been a person who wants to Know Things, so I turned from Narnia to fairy tales and Greek mythology, and I never looked back.Some of it was, even from a very young age, it seemed to me like there was more space in those other, older stories. As you know, Catholics don't interpret the Bible literally, but still, Hell is Hell. And for a much of my youth, Heaven seemed like it pretty much had to be something like Church turned up to 11, which I knew I was supposed to think was awesome, but honestly sounded kind of boring. Whereas Hades, or the Elysian Fields, or Annwn, well, those places had room in them. You could go and Have Adventures. You could go and come back. Those stories had cracks, had interstices, had places where I could imagine things.There was also space to disagree with the older, and non-Christian stories. It took me quite some time to be able to look at the Christian mythos and say, oh, hey, this thing here, it's a problem. Let's talk about why that's a problem, and maybe address it. Whereas it was a lot easier to say, oh, man, that Zeus. He should really maybe ask a lady before attempting swan-shaped congress. And for me at least, when I'm engaging with those older stories in my writing, a lot of the times I am engaging with them because of the problems, because of the raw edges, because I disagree with the story as it has been told.Especially considering the women you named above (Medea!), I am wondering if this is a similar thing for you.Oh my god, my poor Sunday-school teacher, he was just some nice hapless volunteer dad, and here I was pointing to the Old Testament at the age of six, saying, you know, "So this passage here where Lot offers his daughters up to the townspeople, can you clarify what exact transaction is occurring here?"Anyway, for me there is more space for retelling in the older stories. The female saints, to me, are largely very passive--I know lots of other women disagree with this, and see the saints' narratives as ones of resistance and strength, but those elements just aren't there for me. (Like you said, boobs on a plate and virgin forever: super not appealing.) But "evil witch" or "lady who bakes her husband's children into a pie and feeds them to him," I could rewrite those stories all day. I love female characters who are terrifying and amoral and sinister and straight-up evil, whatever that says about me.I guess for me growing up Catholic was just a straight route to the pagan. I still have a lot of reverence for the symbolism; when I was in Europe, I went in literally every cathedral I passed, and a lot of them were so beautiful they made me cry. But that wild mystery isn't there for me in the church (or the Church). You and I both write in the tradition of the fantastical--what made you go there, instead of more mundane (for lack of a better word) retellings of traditional feminine narratives?Part of my attraction to the fantastical is that those were the stories I grew up loving. I mean, there were about two years where I wanted desperately to be cool, and I thought that maybe if I read Sweet Valley High and Babysitters Club, I would be. It didn't work. Though it was in a SVH book where I first read Edna St. Vincent Millay, so there's that. But I never recognized myself in those stories - there was no place in them for someone like I was, or at least, someone like I saw myself.Whereas I could see myself in Meg Murray, in Madeleine L'Engle's books. I wanted to be a girl version of Bran (because he had the coolest Dad and the best dog) in Susan Cooper's Dark is Rising books like nothing else. Those stories, the stories of the fantastic, were my stories, and once I turned back to them (it was Jane Yolen's Briar Rose that rescued me) I pretty much never looked back. The fantastic was what I steeped myself in.But also, I love the possibility for metaphor in the fantastic. Like, if I want to talk about how high school is hell, if I'm working in the fantastic, I don't have to spend the time building up all these layered references that maybe a reader will get, and maybe they won't. I can just set the building on a Hellmouth (hello, Buffy) and start from there. I get to start my story at a different place, and have a different sort of conversation with a reader that way.There is also the question of, as you put it, the elements available in the narrative. I've always been very interested in women's stories. And at least at this point in my writing, the tropes of the feminine that I'm most interested in engaging with and subverting are the tropes of the fantastic.Oh, totally. I teethed on the Dragonlance books--which are sort of wonderfully terrible, but even in those books there are more options for ladies than just "babe." (I mean, you can be "babe magician," "babe warrior elf," "babe dragonlord," etc.) And Patricia C. Wrede (who in retrospect is totally feminist), Madeleine L'Engle, Pamela Dean, Jane Yolen, Ursula K. LeGuin, Elizabeth Hand, Mercedes Lackey... it wasn't a conscious thing at all, when I was a kid, but I grew up reading so many women writers who were using the fantastic in really political ways (or even just writing interesting female characters, which I didn't find nearly as often in the more conventional fiction I was reading). And then I discovered writers like Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany, who were using speculative fiction to talk about race as well. And, too, there's just a sense of possibility in speculative fiction--there are no limits to the world you can make up, other than the limits of your own capacity to imagine. I think at its best there's such a great willingness to take risks in speculative fiction, to really push the limits of what a story can do or talk about. And sometimes it's just really, really fun. I mean, I remember reading Interview with the Vampire in eighth grade, and thinking, THIS IS EXACTLY WHAT ADULTHOOD MUST BE LIKE I CANNOT WAIT.Which did not turn out to be true, unfortunately.For me, that sense of possibility in speculative fiction is also the thing that engages me as a writer. And, to bring the conversation sort of back around to where we began, it's also the thing that engages me as a person of faith. I wrote my dissertation on the writings of medieval women mystics, but I dedicated my dissertation to Madeleine L'Engle, because it was through her presentation of the idea of tessering that I understood the writing of the 14th c. mystic, Julian of Norwich. And in my head, it made complete sense to view a medieval mystic through the lens of a 20th century science fiction writer. Part of the sense of possibility that speculative fiction has for me, is that way of engaging with the numinous, of the impossible, of the things out there that are bigger than I am. Reading speculative fiction expands my capacity for belief, and I don't just mean belief in the sense of faith, but in the sense of everything. In what we as humans are capable of. For me, it is that possibility that is most worth believing in.Right--and for me, coming out of the same background, I ended up in a different place spiritually (like, The Land of the Hippie Witch), but a very similar place in terms of aesthetics and what I'm drawn to and the kinds of stories I want to tell. All those different mythologies I grew up with complemented each other in rich and very rewarding ways. I love your suggestion that story can expand our sense of faith. And, of course, hippie witchery.February 11, 2013

Guillotine 2013

GUILLOTINE 2013 is pretty much the most exciting thing ever, what can I say. I am beyond thrilled to be publishing these unbelievably amazing writers, all of whom are going to light your ass on fire and send you out into the streets bellowing REVOLUTION RIGHT NOW MOTHERFUCKERS, I promise, plus if I do say so myself these books are so PRETTY. You can preorder the next chapbook in the series, Kate Zambreno's Apoplexia, Toxic Shock, & Toilet Bowl: Some notes on why I write this very minute, plus a special BONUS EDITION with a fancy LETTERPRESS POSTER.

KATE ZAMBRENO :: APOPLEXIA, TOXIC SHOCK, & TOILET BOWL: SOME NOTES ON WHY I WRITEchapbook. $6. 16pp. 4.25”x6.25”. hand-bound. spring 2013.

“A girl is a gun. A woman is a bomb”: An essay on writing, madness, rage, and being female, from a relentlessly provocative and brilliant thinker.

KATE ZAMBRENO is the author of the critical memoir Heroines, published by Semiotext(e) in November 2012. She is also the author of the novels Green Girl and O Fallen Angel. Her anti-memoir, Book of Mutter, will be published by Counterpath Press in March 2014.

SHIPS IN MARCH 2013 // PREORDER HERE

SPECIAL EDITION: A copy of Apoplexia, Toxic Shock, & Toilet Bowl: Some notes on why I write & a letterpress broadside of NO MORE WIRE HANGERS. PREORDER HERE

And coming up:

MIMI THI NGUYEN & GOLNAR NIKPOUR :: PUNK: A CONVERSATIONchapbook. $10. 32 pp. 4.25” x 6.25”. hand-bound. summer 2013.

Punk is an unwieldy object of study--because of fictions that circulate as truth, absences in archives and the questionable subject of recovery, and the passage of “minor” details into fields of knowledge. A conversation about the politics of methodology, and historiography, of subculture.

MIMI THI NGUYEN is an Associate Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies and Asian American Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and the author of The Gift of Freedom. She has made zines since 1991, including Slander and the compilation zine Race Riot. Nguyen is a former Punk Planet columnist and a Maximumrocknroll shitworker; she is also a frequent collaborator with Daniela Capistrano for the POC Zine Project.

GOLNAR NIKPOUR served as co-coordinator of Maximum Rocknroll between 2004 and 2007. She is also a founding editor of Blta’arof, a magazine featuring art, literature, historiography, and cultural critique related to Iran and its diaspora. She was born in Tehran, Iran, and lives in New York City.

EVE KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK :: CENSORSHIP & HOMOPHOBIAchapbook. $10. 32 pp. 4.25” x 6.25”. hand-bound. winter 2013.

“It is speech and visibility that legitimate us. It is speech and visibility that give us any political power that we have”: A richly personal and incisive unpublished 1990 essay on free speech, homophobia, and violence that is as relevant now as it was the year it was written.

EVE KOSOFKY SEDGWICK (1950–2009) is widely regarded as one of the originators of queer theory. A poet, artist, literary critic, and teacher, her books include the groundbreaking Epistemology of the Closet, Between Men, and Tendencies.

January 25, 2013

A Conversation with Erica Lorraine Scheidt

Uses for Boys

240pp. St. Martin's. 9781250007117

I came across Erica Lorraine Scheidt's Uses for Boys by chance recently, and what a happy chance it was: it's been a long time since I was so moved by a book. Its narrator, Anna, is left increasingly alone as her mother pursues a string of men; Anna soon realizes she can fill the empty space of her mother's absence with boys of her own. Her new friend, Toy, pulls her into a world where both girls invent the kinds of selves they want to be, but Toy has secrets even Anna doesn't know. When Anna meets Sam, a boy whose joyful and caring family is the kind Anna didn't even know existed, she begins to understand that love--as Francesca Lia Block says--is a dangerous angel indeed, and that trusting other people can be one of the scariest things of all. Scheidt can pack acres of meaning into a single, spare sentence, but even more compelling than the beauty of her prose is Anna herself: vulnerable, resilient, resourceful, and so real. Uses for Boys is the kind of book that that shifts the tint of the world around you long after you've turned the last page.

One of the many things that Uses for Boys does beautifully is explore the ways in which sex can be both empowering and damaging for teenage girls--often at the same time. There are so many moments in this book that just killed me, they're so perfectly framed. You've said that you "started out thinking [you were] going to write about all the reasons a teenage girl has sex" and that the book went somewhere completely different, as books are wont to do--can you talk about that shift a bit?

I did. I wanted to write about a girl who makes all of the mistakes you can make after becoming sexually active and how your experiences might be good and affirming and surprising or they might be confusing or disappointing and some are regrettable or awful and how it's a mix and it's new and you have all these desires and worries, all tangled up.

And maybe, in some ways, I did. But as I wrote about Anna, she became so much more than a string of her experiences with boys. She wanted to know where she belonged and her mom played a huge role in architecting that question, but then didn't help answer it. And then, for a long time in writing this story, I was most interested in Toy. Because having a best friend means that you do belong somewhere.

It’s funny how you end up with the book you end up with. I was asking questions that only writing the whole book could answer.

It's interesting to to see the book described as "dark"--to me, it's incredibly hopeful. Anna is such a strong and complex character--there was no point where I doubted whether or not she was going to be okay. There also seems to be some pushback in terms of Anna's sexuality, and it is exhausting to me (as both a writer and a human being) to see that the idea that some girls do work through loss or loneliness or pain or any number of things through sex is still this completely horrifying idea--like, god forbid we recognize that teenage girls have sex, period, let alone promiscuous or complicated or sometimes troubling sex. Were you surprised to see those reactions?

I so appreciate that. I see her story as hopeful, too.

That some see the book as dark, unrelentingly dark, was a surprise. I think Anna has some terrible experiences--nobody even comments on the street harassment, which to me is one of the really dark moments in the book--but I don't see her story, the way that she tries and reaches and keeps moving forward, as dark.

And sex, I don't know. I guess I expected some of that. Sex is just like that. Sex is physical and messy and intimate and complicated and talking about it makes us uncomfortable.

Right; I think one of the things the books also deals with is how hard it is to figure out your own sexuality as a teenage girl when the world around you is so unsafe. Anna's mom is such a heartbreaking character, too, as someone who's never learned any of the lessons that Anna is already figuring out. Did you know all along that Anna's mom would be so dependent on men, or did she evolve as the book evolved?

Exactly. That's what's dark--when a kind of sexual interest is imposed on us, whether we're participating or not.

[As for Anna's mom,] I don't know, Sarah. So much changed in the drafts and redrafts. I always knew the adults in Anna's life would not be there for her. One of my earliest notes about the book, from 2007, reads: "Anna takes on a kind of mock-adulthood with her own apartment, her own friends and her own love affairs."

So probably. Probably I knew that Anna's mom would be looking for a husband or boyfriend to change her circumstance. I was very influenced by Ang Lee's film (based on the book by Rick Moody), The Ice Storm. The adults in The Ice Storm have no idea how their actions and obsessions affect their children. It's so starkly portrayed. I think that's what I was going for with Anna's mom, that kind of willful blindess.

I LOVED The Ice Storm. Yeah, you can't hate Anna's mom, as much as you want to, as a reader--she's so lost and so oblivious.

You've talked a little bit elsewhere about your own path to being a working writer, which was a bit circuitous, yes? Would you describe yourself as someone who does things the hard way? How do you think that affected you as a writer?

Right? That film is perfect.

Do I do things the hard way? Probably. When I was younger, It was very important to me to be seen as alternative, so when everyone went one way, I obstinately set off in the other. It's not bad, but it doesn't always serve you, you know?

And I studied at a place where being an outsider was highly valued. I was at Naropa at a time when all these amazing folks were there, like Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs and Marianne Faithfull and Jim Carroll and Diane DiPrima. But after college, I had a hard time. I had no idea how much of writing was just keeping your butt in the chair.

And, I gotta say, I do. I write the hard way. I lean into the question of what I'm writing, instead of knowing where I'm going. I try and try and try to outline, but that never works. What fascinates me about a story is what I don't know. Circuitous, actually, might be an apt description.

January 7, 2013

Some Books I Have Been Reading Lately

I am in Seattle for about five minutes, thinking about absolutely nothing other than the next Dabob oyster I am going to stuff in my face and the next FOUR DOLLAR OLD OVERHOLT WELL (!!!!!!) I am going to pour down my throat and completing Sue Grafton's entire catalog (seriously, how is Kinsey Millhone so awesome? Those books never get old), but I did do a lot of other reading in the last few months, I swear. (Why is everyone in Seattle trying to fucking say hello to me all the time, do I look friendly, no I certainly do not.) (I desperately miss vegetables that are not shrinkwrapped in plastic but not quite enough to move back here but man, those are some fine fine vegetables they got at the Ballard Farmer's Market.) Do yourself a favor and go out and read all of these at once, why don't you.

Natalie DiazWhen My Brother Was An Aztec

124pp. Copper Canyon. 9781556593833Oh my GOD, Natalie DIAZ, oh my GOD. This book is so fucking good, so perfect, like mumble-to-yourself-on-the-train good, like every poem is a complete world that guts you good, like, I can't even. Imagine me turning around in circles and waving my arms. I know that's not an actual book review or whatever but it seems sort of insulting to act as though I am smart enough to say anything worthwhile about this book. Just go read it and then thank me later. You keep your eye on Natalie Diaz, y'all, because she is going to be hells famous. You can read a great interview with her here.

Dirty Weekend

OP.Imagine if TGWTDT was a. actually feminist b. actually funny c. actually written by an actual lady and not some sleazy creeper jonesing for a Lara Croft of his very own OH WAIT, SOMEBODY WROTE THIS BOOK ALREADY, in 1991 no less. I cannot even tell you how fucking funny and dark and brilliant Dirty Weekend is or how satisfying it is to read As A Lady. "This is the story of Bella, who woke up one morning and realized she'd had enough," and holy shit, has she. Hat tip to Elizabeth Hand, who recommended this (how had I never read it before?!). It is out of print, I think, but you can track it down on The Behemoth To Which I Will Not Link, or find it in your local used bookstore, hint hint.Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi

Fra Keeler

128pp. Dorothy. 9780984469345 Fra Keeler takes place more or less entirely in the labyrinthine corridors of its nameless narrator's mind, and it's a delicious, intensely paranoid thriller that ranges wildly between dark humor and total claustrophobia. I kept thinking of HP Lovecraft's hyperparanoid, whacked-out narrators (though there are no sea-stinky aliens in Oloomi's compact, restrained, and elegant book). You can read an excerpt here.Cory Taylor

Me and Mr. Booker

216pp. Tin House. 9781935639367Tin House has been knocking it out of the park lately (I also loved, loved, loved Alexis Smith's brilliant, gorgeous Glaciers, Véronique Olmi's devastating Beside the Sea, and Leni Zumas's very dark, very sharp The Listeners), and Me and Mr. Booker is the latest in this line of gems. The story of Martha, a wisecracking and deeply jaded 16-year-old in small-town Australia who takes up an affair with the very much older, very married, and very alcoholic Mr. Booker out of a wild desire to be anywhere other than where she is, Me and Mr. Booker is a perfect balance of relentlessly funny and deeply sad. Martha is a fabulous and immensely engaging narrator, and Cory Taylor effortlessly pulls off the neat and nearly impossible trick of making the reader understand what she sees in Mr. Booker even as we see right through him. Suzanne Scanlon

Promising Young Women

160pp. Dorothy. 9780984469352Like Fra Keeler , Promising Young Women is from Danielle Dutton's exceptional small press Dorothy, A Publishing Project --and like Fra Keeler, it's brilliant. Promising Young Women is a series of loosely interconnected stories sort-of-narrated by "Lizzie," a young woman repeatedly institutionalized for depression; but Lizzie shifts throughout the book as much as the narrative itself does, resulting in a dreamlike, polyphonic pastiche. Scanlon brilliantly undermines the narrative of "girls with problems," even as she reconstructs it. You can read an excerpt here. (And Danielle Dutton clearly has such impeccable taste I cannot wait to spend the next couple of months gleefully devouring Dorothy's backlist.)Cornelia Read

A Field of Darkness

336pp. Grand Central. 9780446699495I fortuitously stumbled across Cornelia Read's debut during my neverending search for Crack-Like But Intelligent Books That Are Sort Of Like The Secret History, and finished it last night at three in the morning, chewing on my fingers in a frenzy of anxiety. Cornelia Read has packed in all my favorite things: a smartassed and scrappy lady narrator, Sketchy Rich People, compulsively readable plotting--even larger social commentary, worked in with a subtle point. And apparently the sequel includes Sketchy Rich People AND Creepy Boarding School? COUNT ME IN.

December 29, 2012

Happy New Year

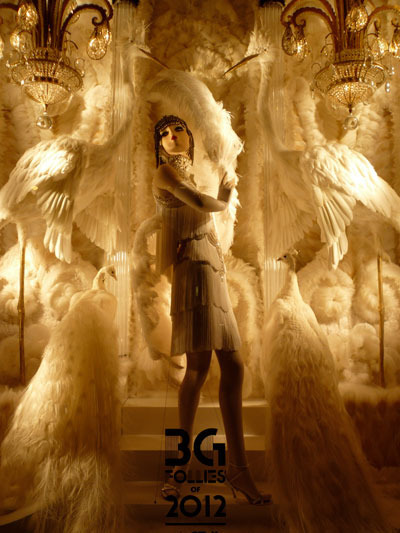

Every December I take the train up to Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Seventh and go look at the Bergdorf Goodman holiday windows.

It's weird up there and there is nowhere in the world that can remind you of how much money you don't have like Fifth Avenue and the bushes outside the Plaza Hotel are teeming with rats and the sidewalk outside Bergdorf Goodman reeks of horse shit from the carriages in Central Park, and that's New York for you. I felt very rock and roll when I left my house that morning in my falling-apart Cult shirt and tight black pants and beat-to-shit boots but in the mirror of Bergdorf Goodman I just looked poor. But that's okay. I am home now and I feel rock and roll again.

After I took pictures of the Bergdorf Goodman windows we looked up a ramen restaurant on my friend's Internet phone and a very old man came up to us and shouted "OH LOOK HERE I AM GETTING MY EMAIL FROM THE TOILET, HERE I AM WITH MY EMAIL, YOU PEOPLE ARE SO BORING," and then he tottered away.

I am posting these days late--a week late? two weeks late? I don't even remember--because it has been that kind of month, that kind of year--but pretend for me, wherever you are, that you are suspended in a moment of magic on a frozen sidewalk in New York, looking up with your mouth open a little, wishing for snow to catch on your tongue. Remembering that beauty is everywhere and especially in the most unlikely places.

Happy New Year to you, dear creatures. Here's to a hell of a 2013 for all of us.

xo

sarah

December 17, 2012

C'est Nous: A Conversation In Solidarity with the Girl

SARAH: Both of us took some serious umbrage with Emily Keeler's review of Kate Zambreno's most recent book Heroines in the Los Angeles Review of Books, and our frustrations with that piece tie rather nicely together with a lot of other conversations we've been having lately about public performances of femininity (and the Perils Thereof). I'm not even sure where to start unpacking the review, but I think one point of entry is the idea--which is certainly not limited to a single reviewer--that women's attention to, and interest in, fashion and presentation is inherently problematic, shallow, and invalidating of our intellectual capacities. That "a glittery silver toenail polish from OPI's Swiss collection" has no value as a signifier (as opposed to, I guess, a byline in the LARB). (To be clear: I haven't yet read Heroines, though I'm a fan of Zambreno's earlier novel Green Girl and her blog, Frances Farmer is My Sister.)

MEG: Clearly there's about five hundred directions in which we could take this, and I'm not sure where to start either.

As for your not having read the book yet, it seems that Keeler's criticism is about a lot of ideas beyond the text. I think this was part of our "WTF, LARB" response. It was partially a defense of Kate, whom I know we both think is brilliant and like As A Person too, but also a reaction to what we both find to be a familiar and tired critique of the ladies at large. Emily Keeler is talking a lot about women and fashion and hysteria, more so than about Kate's book. I find it interesting that she liked Green Girl( which is rife with such "shallow" obsessions like clothes, makeup, sex, etc) but disliked Heroines for these same motifs? I have a lot to say but am still trying to get to the root of what upset me so much.

Keeler writes: "What does it mean to reject the psychopathology offered by Zambreno--as a reader, as a writer, as a woman? To disinvest myself of disorder in my response to this text? To reject hysteria and mania, to refuse the glamor of the broken woman writer?"

Which is not something I entirely disagree with. It would certainly be nice--or at least more productive--to disinvest myself of disorder, to "fix" everything, per se. I don't think being a broken woman is particularly glamorous; I would like for eating disorders to not exist and I would like if we weren't fascinated by coked-out tragic starlets in the tabloids. It would be real nice if nothing about being a lady related to the aforementioned psychopathologies. But this simply isn't how it is, and to ignore (and scorn) the messy neurasthenic (and her wardrobe and makeup) doesn't make any of us better. We don’t need to refuse or reject the hysteria--but not-refusing isn’t necessarily praise, either. It just is, and it’s worth thinking about.

Keeler also reacts against the rigid gender binaries set up in Heroines ("HIM" and "HER") which is of course something I'm also down with.But I don't read anything Kate's ever written, or any l'écriture féminine for that matter, as an endorsement of those binaries as much as an indictment of that system, a testimonial to how shitty and confusing it can be living in a world that's set up like that.

SARAH: Exactly, I think that's the frustration--I'm sure there are valid critical points of contention that a reviewer could have with this book specifically, but "I don't think women should talk about shopping" isn't one of them. And it's so frustrating to still be having this conversation, which we have been having for decades now, that boils down to, you know: WEAR LIPSTICK. DON'T WEAR LIPSTICK. IT'S FINE. NOBODY IS MAKING YOU WEAR OR NOT WEAR LIPSTICK. And, shockingly, I can wear lipstick without it disabling any of my considerable critical faculties.

I do think there are places where frustration with those narratives of feminized pathology--like anorexia and bulimia and the coked-up starlet/Marnell--is productive. It is certainly a messiness that's more allowed of conventionally attractive, white women--though I don't think those women fare all that well either, when you look at the larger culture's reaction to their narratives. And sometimes I think that messiness is presented as the only way to perform femininity, or there's an assumption that all "female" experiences have to involve self-abnegation and hysteria.

But at the same time, criticizing writing by women as being too feminine is just deeply, deeply problematic. And it totally erases as well the radical potential of the feminine--I'm thinking about the ways in which women (trans/queer/of color) who have historically not been allowed to perform what we read as the feminine (or have been, and are still, physically assaulted and killed for performing what we read as the feminine) have reclaimed those performances in really radical ways. And even for someone like me, who's privileged in many, many ways, subverting that feminine, appropriating it to my own ends, engaging with it--it's not at all, for me, participating in a rigid gender binary. And it's not for anyone I know who presents as femme in any way. That's a pretty heteronormative assumption, that the only way to present as feminine involves complicity with gender binaries.

MEG: Totally. And even WITHOUT taking into account those infinite radical possibilities (that queers communicate widely through fashion is thing I could go on about for hours) --even when we're talking about boring ole pretty straight white cisladies with money--I find it very difficult to write off clothing, style, fashion, femininity, whatever.

My blog (well, used-to be blog, now it's more of a messy tumblr scrapbook) is named Good Morning Midnight after the Jean Rhys book (which I know was also influential and inspirational to Kate Z.). GMM was basically life-changing for me the first time I read it, sophomore year of college in a required-for-major modernism class. It was the first thing I'd read that made the all-too-familiar feminine mundane something utterly compelling, heartbreaking, even terrifying. A gateway into countless other writers and ideas that said: no, this is interesting and fucked up, and we don't have to not talk about it because it's silly play stuff for girls.

There's one scene in GMM which still gives me chills and which explains all of this to me. Our protagonist Sasha is wandering Paris, depressed and drunk, trying to re-invent and fix her broken life, dying her hair, buying dresses, crying in restrooms. She spends two hours in one shop searching for The Perfect Hat That Will Fix All The Things, and the shopgirl says, over and over, "All the hats nowadays are very difficult to wear." (Here's the whole passage.)

And we understand, immediately, the depth of meaning behind that one comment, "All the hats nowadays are very difficult to wear." Hats as a common metaphor for roles and lives, of course, but also as a testament to the difficulties of femininity, the impossibility of ever "getting it right," especially "nowadays." (Note that Sasha is pleased with the hat not because it draws positive attention, but because nobody stares. She looks like the right kind of woman, she passes as "normal," if only for a moment.) Sasha's paralysis and depression and plight and lack of independence and indecision are all so perfectly encapsulated by this one heartbreaking scene--this trivial experience of buying a hat. This stupid thing that is shopping.

Recording the experience of buying a hat--or of what one's wearing in a museum, or of what symbolic meaning (or just aesthetic appeal) one finds in nail polish--can be far more than little girls yammering about clothes. Even on a casual level (we needn’t always be critically engaged) sartorial language is something we all use to communicate.And hell, what makes talking about clothes necessarily more shallow than food, or the weather, or the fickle G train? I'm pretty sure you and I became friends because you linked to an outfit post I made of a sweatshirt with a sharpied-on Chanel logo (which somehow lead into email chains about Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick) and I don't feel bad or depressed that our friendship came out of that.

SARAH: I don't feel bad about it either; I feel just fine. And our friendship could have come out of any number of other points of commonality, and I have plenty of friends who have no interest in clothes whatsoever. It's not a zero-sum game. Keeler’s accusation that Zambreno "glamorizes" the "broken woman writer" also seems unfair. There's nothing glamorous about Green Girl. There's nothing glamorous about being destitute and fucked-up and knowing the only commodity you have to trade on is your physical appearance, which Jean Rhys writes about incredibly, and there is certainly nothing glamorous about her heroines.

Keeler's invocation of Madame Bovary is this weirdly apt unintentional meta-ness--I mean, Emma Bovary is a fictive flibbertigibbet constructed by a man who was fundamentally misogynist; you want to talk about the actual process of who is doing the marginalizing, of who is appropriating and sidelining women and women's desires and women's work, that's a pretty neat metaphor right there. I love Madame Bovary, it is a book that never fails to delight me, but Flaubert's critiquing femininity because he doesn't like women, not because he has anything astute to say about them. (To be fair, Flaubert doesn’t like anybody .) What he's simultaneously skewering and admitting to is Emma's romanticism, which doesn't seem to me to apply in any way to women who were writing about their own experiences of madness, poverty, survival. Subverting glamor, c'est pas toi, no bigs. But dismissing it altogether seems lazy at best.

Ultimately, my frustration with the review is that it comes off as that tired old move of pointing out how dopey all those dopey girls and their dopey clothes are, when the real intellectual work is being done over with the boys and their important thoughts about important things. "I'm not crazy, I'm not like that, I am not her kind." I don’t think Emily Keeler, or any single reviewer, or even the LARB, is the problem; the culture is the problem. But I do wish we could move past these kinds of conversations.

MEG: I also want to note that Keeler's criticism is something I'm not immune to or even not guilty of myself. I still catch myself turning up my nose at girls for doing girl shit: giggling too much or having emotional breakdowns in public or making diaries of their outfits, even though I do those things too. So there's this internalized fear, too.We're told that if you're not that kind of girl you must be smarter, better, stronger, etc.--and it's hard to break away from that. It's hard to value those trivialities of performed/required femininity because 1.) we're told we must do them to be of value to the world and 2.) we're told that they're not valuable, and that we'd be more valuable without them. And that's a hard thing to recognize.

And that’s what I try to disinvest myself of, I think. Not of the disorder, but of the shame or fear of disorder and shallowness. I want to support other women so I can support myself. I want to validate their experiences and writing, the incredible spectrum of talent and lives which that can include. I have to police myself to not be critical of women for being women--myself included. Which is part of what I like so much about Kate Z's (and a lot of other women’s) writing: I find it validating to embrace that, to examine (or enjoy or loathe) the minutiae of the lives of girls, all kinds of girls, regardless of race, class, gender, etc. I find it the opposite of depressing, and the opposite of shallow. I guess that's the sentiment I was reacting against so strongly.

There's that Virginia Woolf quote that I tweeted and that I also use everywhere as my "about me." And it amazes me that Woolf and Rhys--these modernists who show up in Heroines--were writing about these same things, and that we still haven't been able to understand or conquer this internalized fear of ourselves.

SARAH: Amen to that.

Sarah McCarry blogs at www.therejectionist.com, obviously. Meg Clark writes and lives in Brooklyn and blogs at morningmidnight.com.

December 12, 2012

The Next Big Thing

I am not the best at talking about MY BOOK, which is sort of funny, as I am quite aces at talking about MY SELF and MY DEEP THOUGHTS. But you know. Writers! Bunch of fucking weirdos! When Charles Tan invited me to participate in the Next Big Thing blog series, it seemed like a fine time to at last make some attempt to remedy my current Marketing Strategy, which consists of "Look about furtively and rapidly change subject when asked about book." Thanks so much, Charles! (Charles has got a very fabulous speculative fiction anthology which you ought to read, btw.) Next week look for posts from writer-friends Stephanie Kuehn, Shirin Dubbin, and Ibi Zoboi.

What is the working title of your next book?

All Our Pretty Songs , which is the actual official title. You can befriend it on Goodreads and here it is at Powell's.Where did the idea come from for the book?

It is a very loose and very goth retelling of the Orpheus and Eurydice story.

What genre does your book fall under?

Books by and for people who cry reading Rimbaud on the train.

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

I don't care as long as one of them is Gary Oldman circa 1992. I am sure we could find something useful for Idris Elba to do also.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

In the wild, thriving music scene of 1990s Seattle, a tough, punk-rock heroine follows her best friend and her lover into the underworld and finds more than she bargained for.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

I have an incomparably wonderful agent and editor; the book is coming out from St. Martin's Press in July 2013.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Thirty-three years.

What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

If by this do you mean "Do you, Sarah McCarry, owe an unrepayable debt to The Secret History, Tam Lin, and the entire oeuvres of Angela Carter, Elizabeth Hand, and Francesca Lia Block, with bonus style inspiration from that 1993 Perry Farrell movie Gift," the answer is "Yes."

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

The Hedi Slimane shoot of Frances Bean Cobain, the Olympic Peninsula, a youth happily misspent pounding the shit out of other teenagers in mosh pits up and down the I-5 corridor, the human impulse towards the ecstatic, and the opportunity to pepper an entire novel with way too many references to the X-Files, the Jesus and Mary Chain, and Nag Champa.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

The first page, hopefully:

JULY

Aurora and I live in a world without fathers. Hers is dead and mine was gone before I was born. Her house in the hills is full of his absence: his guitars in every room, his picture on all the walls, his flannel shirts and worn-through jeans still hanging in the closets, his platinum records on the mantle of the marble fireplace that is so big we both used to crawl inside it when we were little. He is everywhere, and so we never think about him. Aurora’s mother is a junkie and mine is a witch. When I say it like that, it sounds funny, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true.

This is a story about love, but not the kind of love you think. You’ll see.

Aurora and I grew up like sisters and this is how we match: same bony, long-toed feet, same sharp elbows, same single crooked tooth (Aurora’s left canine, my right front). Same way of looking at you out of the corners of our eyes until you blush. Same taste in music: faster, harder, more. Same appetite. Same heart.

Aurora and I live like sisters but we are not alike. I am tidy and Aurora has never cleaned a mess she made in her life. Aurora sleeps until four if you let her, loves Aliens, smiles often, is the kind of girl who will break into your car to leave you a present you don’t know you want until you find it. Aurora’s mom is richer than anything you can imagine and mine is poor. Aurora is sunlight and I’m a walking scowl. Aurora’s skin is dark and mine is watery cream. She bleaches her black hair white and smokes filterless Lucky Strikes and drinks too much. She wears dresses made out of white lace and gloves with the fingers cut off, Converse with holes at the toes and old-lady satin pumps, and if you think right now of the most beautiful girl you know, Aurora next to that girl is a galaxy dwarfing an ordinary sun.

I am not beautiful at all, but I am mean. Every day I wear black jeans and the worn-out Misfits shirt that used to be Aurora’s dad’s and combat boots with steel in the toes. People keep away from my fists in the pit at shows. I cut my dark hair short and my eyes are grey like smoke when I am happy and like concrete when I am not. Every morning I get up at six and run seven miles, into the hills and back, and where Aurora’s body is model-skinny mine is solid muscle sheathed in a soft layer that all the miles in the world can’t skim away. Aurora breaks hearts and I paint pictures. We are both pretty good at what we do.

December 7, 2012

A Conversation with Leela Corman

Unterzakhn

208pp. Schocken. 9780805242591

Leela Corman 's Unterzakhn is a gorgeous, enthralling graphic novel about two immigrant sisters living in New York's Lower East Side in the early 1900s. Twins Esther and Fanya take very different paths: Fanya, the "clever" sister, goes to work for an doctor who performs abortions, while Esther takes a job in a burlesque theater and brothel. The beautifully drawn story follows the sisters' compelling journey from childhood to adulthood. Unterzakhn is packed with historical detail and vivid characters who come to life on the page thanks both to Corman's skill as a storyteller and her fantastic drawings. But it's more than just a realistic portrayal of life at the turn of the twentieth century; Esther and Fanya's struggles are utterly modern and relatable, and the world in which they live is not so different from our own in terms of the choices available to women. A little bit Luc Sante, a little bit Phoebe Gloeckner, and wholly original, Unterzakhn was one of my favorite books of this year. Leela was kind enough to answer a few questions about the book.

Can you talk a little about your research process for Unterzakhn? How did you research the book? And did you find that the story changed as you gathered information, or did you know the story you wanted to tell all along?

Everything I do is very research-driven. I did know the rough outlines of the story I wanted to tell from the start, but certain things changed as I worked. A lot of that had more to do with what got emphasized, or with clarity, rather than big changes of direction. As for research, every idea generates the need for it. So in this case, I knew where and when this family lived. Now I had to find out how they dressed, what they ate, what their living quarters looked and felt like. And then with each turn of the story, there were new things to learn. The easiest and most fun part is clothing, especially the dresses Esther gets to wear in the final chapter, when she has money. I stole outright from some famous women of the time. In the party scene she's wearing Josephine Baker's dress. In the funeral scene she's wearing Garbo's fur.

The shift in emphasis came as I grew a bit more interested in Esther than in Fanya, probably because dancing is more fun than midwifery, what can I say? But they were both important to me.

It's a bit depressing how much the limitations to women's reproductive freedom in the story resonate today. Is that something you intended? Why did you decide to have Fanya work for an abortionist?

One of the very first motivations for creating this book was to talk about the ramifications of not having any choices. They are grotesque. Fanya working for the abortionist was idea #1. Corsets and vaudeville came later. Yes, it's miserable how relevant this is. In fact, when I first had the idea for this book, it was 2003. The discourse around women's health, rape, and violence towards women in this last election cycle was shocking and so depressing. Though it got a lot of people out to the polls, I'm sure.

In the context of America, it's surprising to me that these things are still an issue. Other countries have their own issues. Look what just happened in Ireland, where a woman having a second-trimester miscarriage was denied an abortion and died in agony of sepsis. What kind of treatment is that? Those doctors should be stripped of their licenses. So that's why I chose to tell a story of what happens to women in places where they aren't allowed to make their own reproductive decisions. It's inevitable that women will die or be maimed. We just watched Mike Leigh's Vera Drake again the other night; it's the same story. It made me so angry.

I was struck by how much you subverted the reader's expectations for your characters--I thought that was very nicely done. Did you know how the story would end when you started to tell it?

Well, what were the reader's expectations? That Esther would come to a bad end and that Fanya with her education would somehow "make it"? Bad girls don't always go to hell--sometimes they end up in a penthouse, breakfasting in silk pajamas. Though I never thought of Esther as a bad girl.

I didn't know how the story would end. In fact, I had no confidence that the ending worked, until I'd finished it and sent the manuscript to my readers for review. When Jason Little, whose judgment I trust immensely, told me it was a great ending, I knew I'd done a good job. Endings are torment!

What are you working on now?

Right now, I'm hoping to get started on some adaptations of Isaac Bashevis Singer short stories, and I'm in the early stages of research on my next long graphic novel, a three-part book about entertainers in different times in history. Right now I'm researching the Black Death and music of the fourteenth century. I'm doing a one-pager for Women's Review of Books, and hoping to get some more straight illustration work soon, after years of only working on this book!

What are some books you've read lately and loved?

I can't say enough about the last couple of Love & Rockets books. What Jaime Hernandez did there is just unmatched. Arcadia by Lauren Groff remains my favorite recent novel. I also really loved Jeet Thayil's Narcopolis [As did I. --ed.] Carol Tyler's You'll Never Know, and Jack Weatherford's Ghengis Khan And The Making of the Modern World. I just started reading A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century by Barbara Tuchman [This book is SO BALLER. --ed.], and I've got Dave Lasky & Frank Young's Don't Forget This Song, a graphic biography of the Carter Family, waiting for me whenever I decide to pull myself away from plague pits and flagellants.

Sarah McCarry's Blog

- Sarah McCarry's profile

- 156 followers