Francis Pryor's Blog, page 24

December 29, 2012

Hazel Nuts: Britain’s first farmed food? Part 3

In this experiment I was not so much concerned with yield, as with storage. Having grown hazels for nearly twenty years, I do not need to be convinced of their productivity and to some extent estimates of ancient yield are pointless: everything would depend on the number, cultivation, location, selection and pruning of bushes; but having said that, I can see no reason whatever why they could not have been a major staple – maybe even comparable with cereals, especially in the early Neolithic, when woodland cover was still extensive. To give an example of possible yield, a fully grown cob nut (i.e. Corylus maxima), some two metres away from the young hybrid bush we used for this experiment, yielded a crop of some 2,860 gm. when harvested in early September 2009. By this time, however, grey squirrels had started to move in, and it didn’t prove possible to reach the very highest branches. So the bush’s actual yield would probably have been rather higher – perhaps up to 3,500 gm.

Three trays of nuts from a single cobnut bush, harvested in September 2009. Together these nuts weighed 2,860 grams. Please note that the central tray is resting on the rim of the large ceramic bowl – despite appearances, the nuts don’t fill it!

The nuts that formed the basis of this experiment were harvested on September 21st, 2006. The husks (the leafy protection that encased the nut shells) were then removed and the nuts were counted (458) and weighed (1580 gm.). The following day and thereafter at roughly monthly intervals until September 2007, when the supply gave out, samples of 100 gm. were weighed-out and counted (with shells still on). The final sample weighed 80 gm. Empty and rotten nuts were recorded and rejected. The kernels were then weighed. Finally the nuts were assessed for palatability taste and texture, the latter using a scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). It should be noted that the term ‘poor’ in this instance means weak or slight, rather than actively unpleasant. In an attempt to replicate prehistoric storage conditions, the nuts were kept in a net sack in an unheated barn. They were not separated into 100 gm. batches until the day they were to be weighed and tasted.

The results showed a small, but steady decline in kernel weight over the experimental period. Rather to our surprise, however, there was only a very small increase in the number of rotten and empty nuts in the latter part of the period. Taste and palatability improved after two or three months storage and was still good after a full year in the barn. Indeed the first new nuts of 2007 were found to be slightly inferior in taste and palatability to those of the previous season. Subjectively, we gained the impression that by September the taste of the old season nuts was just starting to deteriorate with greater rapidity. The results do demonstrate clearly, however, that provided they are kept airy and dry, hazel nuts can be stored for at least a year, without any pre-treatment, such as heating. During this time too they retained their taste and, to judge by the consistency of their weight, their oil content as well. Given this, we can see no practical reason why prehistoric nuts were charred, unless, of course cracked shells, rotten and old-season nuts were used as fuel. Alternatively, of course, they could have been heated in the fire and then cracked open and eaten, possibly with a pinch of salt or dipped into sea water – a process that can improve the taste especially in the early part of the season.

I’m writing this three days after Christmas. During the Festive Season tradition has, as always, been very evident, most of it, I’m afraid’ is merely Victorian, but some, like Carols, rather older. Indeed, the idea of mid-winter rebirth and renewal is a key part of Neolithic monument-building, at places like Stonehenge. But as I munch on one of our Festive hazel nuts that escaped the squirrels, I wonder whether my actions might not have their roots very much earlier, back in the Mesolithic of almost 9000 BC, at places like Star Carr? By this stage of the winter, as our Table shows, the stored nuts were starting to reach their peak of taste and texture. Mesolithic families had far more sense than to stuff themselves with dry, tasteless turkey meat, but I wonder whether roasted nuts wouldn’t have gone rather well with a haunch of venison or some pine-smoked salmon? As I said, some Christmas traditions may well have roots that extend back a very, very, long time indeed. Have a Happy New Year!

The sample of nuts at the time of harvest (large heap). The rotten nuts (small heap) were collected out of interest, but were not included in any of the statistics. Some had probably been knocked off the bush weeks ago; others had been gnawed by wood mice.

A close-up of the nuts at the time of harvest. As time passed the stored nuts lost some of their surface lustre. From this view it’s evident that the bush is a cobnut hybrid, but not an extreme one. These nuts would be rejected by most commercial growers, as too small.

The first sample of shelled nuts.

December 27, 2012

Hazel Nuts: Britain’s first farmed food? Part 2

My interest in hazel nuts began on my first dig, back in 1963 when I was a volunteer excavator on an Iron Age hillfort in Bedfordshire, about half an hour’s drive from my parents’ house. I’d just passed my driving test and was keen to be independent, albeit in my father’s car. The next dig I went on, the following summer was a mere fifteen minutes from home and by now I’d acquired a battered Austin A40 which I drove far too fast. It was always breaking down. But again, the site, an Iron Age settlement beside the Icknield Way that survived, like so many others , into Roman times, produced hazel nut shells in profusion. They intrigued me far more than any other finds, simply because I could still see them growing on bushes around the edges of the woods near our house. In my experience most archaeologists find different links, different pathways, that fire their imagination and lead them directly to the past. Often they’re the main reason they decide to join the profession. For some it’s pottery; for others, flints or even animal bones; but for me it was those little nuts. So I owe a lifetime of great pleasure and satisfaction to them. These three blog posts are my way of saying thank you to the genus Corylus.

There were hazel nuts on my first big professional dig, at the huge gravel quarry at Mucking, near Thurrock overlooking the Thames estuary in Essex. But nobody seemed to get excited about them; everyone seemed far more interested in tiny grain impressions on pottery. Then I repeatedly found nuts on my own excavations at Fengate, in Peterborough and also at the Neolithic causewayed enclosure at Etton, just north of Peterborough. At Etton the nuts had been placed within small pits that had carefully been filled-in as part of religious offerings. They appeared to have been part of feasts that also involved pork.

In 1976 I read a paper by the great archaeological theorist, David Clarke.1 It was all about Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and the food they ate and in it he speculated that hazel nuts were far more important than anyone had realised. Unfortunately, he couldn’t produce any statistics from Britain – which was a shame. But it was an excellent paper, nonetheless, and it set me thinking. As some might have gathered from my previous post, when my mind starts working it can be a very slow process – and I’m not even slightly ashamed of that. I like things to turn over, as it were, on the back burner. And that was what was happening in this instance.

Nearly twenty years later, we bought two fields in the south Lincolnshire Fens, where in 1994 we built a house and established a small sheep farm, garden, woods and orchard. The woods included about 400 hazel bushes which were inter-planted with oak standards to draw them up and help produce good long, straight rods and poles. These hazels were meant to be coppiced, to provide the garden with pea sticks and bean poles and, more importantly, to give Flag Fen a reliable supply of coppice rods to use in hurdles, fences and wattle-and-daub walls. Sadly the entire project is now being threatened by Muntjac deer – damn them.

While the woodland hazel bushes and oak trees were establishing themselves, Maisie and I decided we’d also like some hazel nuts to eat. So we planted a double row of cobnuts in what we rather grandly refer to as the Nut Walk. Beneath it, the ground is covered by snowdrops, aconites and squills and, though I say so myself, looks gorgeous in springtime. When we planted the Nut Walk, in the late 1990s money was tight, so we could only afford three or four ‘proper’ (i.e. grafted) cobnut bushes. Cobnuts belong to a different species of the genus Corylus: C. maxima. Anyhow, I planted the rest of the Nut Walk with seedling plants that I found close by the bought-in nuts, hoping they’d be good fruiters. But the chances are that they’re far from ‘pure’ cobnut, as hazel is wind-pollinated and the wood with its hundreds of wild (i.e. avellana) hazels, is just a short distance away. And I was right, because, yes, the seedlings I planted are very productive, but the nuts they produce aren’t anything like as huge as the ‘pure’ cobnuts. But I don’t really care: it’s the taste that counts and they’re delicious.

I planted the final bush of the Walk back (I think) in 1999 and by now I would imagine the blood-line of the hazels was more avellana than maxima – which by luck was actually what I wanted. But do bear in mind that the figures for nut production produced here may be a little (5-10%?) generous. Although, having said that, I can see no earthly reason why Neolithic or even Mesolithic growers would not have selected for size and taste – they weren’t stupid. Which brings me onto another important point (and not a Digression).

I’d selected seedlings I could see growing around my bushes. But nobody thinks Mesolithic people could have done that, because seeing a small plant manifestly growing out of a semi-rotten nut, is something only a farmer could do. To lift and transplant that seedling, the Mesolithic person would be crossing the revered academic line between food-gatherers and food-producers. And that line may only be crossed by fully qualified, authentic Neolithic farmers. Of course this is absolute bollox. By the same token we were told until very recently that Mesolithic people didn’t coppice willow and hazel to produce long, straight rods and poles. I think that belief was a spin-off of the food producer/gatherer business. Well, we now know they did – and right back to early post glacial times. The thing is, they weren’t stupid. They used their eyes and observed what was going on around them. If a tree was struck by lightning or broke in half in a gale, then long, straight shoots grew at the place where the trunk snapped off. It didn’t take an Einstein to realise that if you did the breaking yourself, then the next summer you could help yourself to rods and withies for house roofs, baskets and fish traps.

Even now you can read in the best archaeological books that hazel nuts are commonly found because people coppiced hazel to use around the house and farm. But I’m afraid that’s plain wrong – and far too simple. So let’s start with that final nut bush I planted back in 1999. I started to do an experiment involving hazel nuts after we’d been enjoying their produce for about five years – in any quantity. In those days, too, our woodland was still too remote from other trees and grey squirrels had yet to traverse the vast open stretches of bare, arable land that surrounds our farm. So we had nuts in abundance. Then, in 2008, the squirrels arrived and for the last four years they’ve stolen our entire crop. But I’ve got plans to defeat them, that involve the spraying of a fine sulphur mist that coats the leaves and makes them unpalatable to browsing animals. Wall anyhow, it’s worth a try. Frankly, anything’s worth a try.

By September 2006 when I started the experiment, the last nut bush was now seven years old, and as you can see from the photo, it was about ten feet high. I had never coppiced it, because I was growing it for nuts. Coppicing makes the bush grow fast and straight. It also discourages flowering and nut formation, as the plant thinks its survival is being threatened by fire, or a man with an axe, rather than dryness or some natural hazard – so it puts all its survival efforts into growing. Then when the few flower buds do start to form, in late autumn, they’re all high up in the branches – and very hard to spot, or pick. I also photographed a coppiced hazel of about the same age deep in the wood, for comparison.

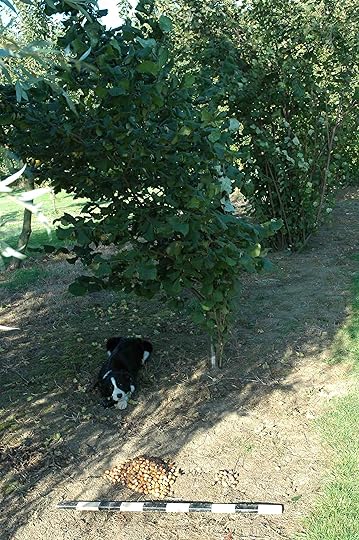

Twink is lying next to the nut bush we planted in 1999. It has never been cut to the ground (coppiced) and the photo was taken on September 21st (the autumn equinox!). In the foreground are two heaps of the nuts we harvested from the bush on the day the picture was taken. The small heap (to the right) are rotten nuts found on the ground. They were discarded and are not part of the subsequent experiment into storage.

A slightly older coppiced hazel bush growing in ash woodland. Note the long, straight growth of the hazel rods. Like all coppiced hazels this produced very few nuts – mostly high on the tallest branches.

3. Close-up of nuts lying on the ground. A few have been opened by wood mice. This is nothing to the damage caused by grey squirrels.

Neolithic and Mesolithic people would have cut their coppiced hazel from plants growing in open woodland, where they’d have had enough light to grow healthily, but still had to struggle upwards to get more. Their fruiting bushes would have grown – or been transplanted to the very edges of the wood, or clearing. Here they didn’t need to strain upwards in search of sunlight which was abundant. But the ground would also have been quite well drained by all the larger trees behind them – so again, lush growth was made harder (hazels love wetter ground). The reduced growth favoured flower production, and being on the edges of the trees there would be plenty of air-borne pollen from the many coppiced bushes, in the heart of the wood. So I’m in absolutely no doubt that the coppiced hazels were not the ones that yielded the seemingly abundant supplies of nuts. As I said, it was more complex than that, and I’m in little doubt either that this sort of sophisticated resource management was taking place from earliest Mesolithic times – to judge from the quantities of nuts being produced at sites like Star Carr (8500 BC).2 In my view they must have effectively farmed the nuts, and if that upsets some of my academic colleagues, all I can say is, I’m sorry.

Now the nut bush I decided to conduct the experiment on, was still far from fully grown, but even so, it produced a large quantity of nuts (see photo). We picked them on September 21st, as soon as they began to fall in any numbers. That meant they’d be fully ripened. Rather to my surprise very few of the nuts we picked-up from the ground were rotten – which came as something of a surprise (the rotten nuts are the small heap in the photo). Now, it’s worth bearing in mind that the nuts from this small bush were more than enough to keep two keen nut-eaters content over winter. Of course, we don’t depend on nuts as a staple, but a few dozen well-tended bushes would provide a large family with an abundant supply of winter protein in even the leanest of years. I still can’t understand why this important source of nutrition has been overlooked by so many people, despite the late great David Clarke’s reminder.

In the next post I’ll describe the results of the year-long experiment into how well those nuts stored. I think you’ll find the results quite startling.

1 Clarke, D.L. 1976 ‘Mesolithic Europe: the economic basis.’ In G. de G. Sieveking, I.H. Longworth and K.E. Wilson (eds.), Problems in Economic and Social Archaeology, pp. 449-81 (Duckworth, London).

2 Conneller, C., Milner, N., Taylor, B. and Taylor, M. (2012) ‘Substantial settlement in the European Early Mesolithic: new research at Star Carr’, Antiquity, Vol. 86, pp. 1004-1020

December 26, 2012

Preliminary Musings: Hazel Nuts: Britain’s first farmed food?

Prehistory and archaeology are subjects where traditions die hard and where orthodoxies can rule the roost for generations. It must be great to prick balloons, but having said that, I don’t think I’m a great believer in acting the iconoclast: in smashing revered images like my spiritual antecedents in Oliver Cromwell’s East Anglia. I don’t think I’d have been in the church, scraping the painted faces of saints on those wonderful rood screens in Norfolk, but I might just have been fetching cups of tea for the chaps with the knives. I think it’s because I like to under-mine, then step back and watch the edifice topple – if it’s going to. Although in my experience it often stands there stubbornly; doesn’t even wobble – and when that happens it’s best to creep off quietly, and wait until the fuss dies down.

I suspect that many academic orthodoxies – sacred cows, call them what you will – come into existence when people with little practical experience of the world are confronted by aspects of the past that they regard as complex and difficult, but which are no such thing, as they’d soon realise if they spent any time out in the wider world beyond the library and laboratory. For example, I can remember reading as a student, that trees could have been felled in the past by ‘ring-barking’ – i.e. by removing the bark in a ring right around the trunk. In theory this stops the sap rising and prevents the upper parts of the tree from receiving water and nutrients from the soil. So, in theory, the tree then dies. On paper, it works, but I can’t say I was ever that convinced. But I suppose it sort of made sense, until a few years later, when I found some sheep that had broken into a young orchard and had completely ring-barked several trees. I think it’s the sweet taste of the sap beneath the bark that they were after.

I can remember walking through the orchard over subsequent weeks and yes, I concede, a few branches did die, many leaves shrivelled and fell off Anyhow, before summer had ended all those trees had recovered – and the bark grew back. With older forest trees, the main trunk might die (and I deliberately emphasise the word ‘might’), but soon the living stump would send up a mass of sturdy shoots and before too long you’d have a perfectly coppiced ‘stool’, which would be something far harder to fell and remove than a simple standing tree, or standard, to give it its technical name. You still read in text-books that Europe’s forests were felled in such ways and I’m now quite certain that much of the literature on the clearance of Britain’s forest cover (such as it was), is plain wrong. And Maisie (who is far more knowledgeable on the subject than me) is currently writing a paper on that very subject.

And there are all sorts of other myths, like the setting of hedges. One of these days I plan to write an article on how hedges can come out of birds’ bottoms. Indeed, I mentioned this topic in some of my first blogs of 2012, but never got round to writing about it. Maybe that’s one for 2013. Right now, it’s nuts that are worrying me. And again, I plan to write a ‘proper’ paper on them one day, but to date haven’t found the time, or indeed, the inclination to go through all the hassle of getting a manuscript all tarted-up: ready for an academic journal and peer review. So I’ll do it far less formally, right here.

The thing is, I’ve other irons in the fire. I’m currently heavily involved writing a book for Penguin. So it’s out of bed at 5.30 every morning and downstairs to my laptop, but this time I’ll avoid putting tea-cosies on my head before returning to our bedroom. The new book was commissioned over two years ago, after the publication of The Making of the British Landscape and the very favourable reception that labour-of-love received. My then editor at Allen Lane (the publishing house behind the Penguin imprint) wanted something on the development of domestic, or family, life and it happened to be a subject that appealed to me. And for various reasons we were quite hard up (self-employment is like that!) and the advance money would be very welcome. So I said yes. Yes, please, even. Then Time Team asked me to be archaeological director on six episodes (which involves quite a lot of preliminary development work), and before I knew it I’d missed the deadline of May 2012. Now there was a time (when I was a callow youth) when I would try to bullshit publishers, but no longer. No, in my experience, it pays to be completely honest with them: cards on table.

Last December I persuaded my nice Editor to give me lunch in London and over plates of Italian food I came clean and explained that writing wasn’t going too well and that I’d probably fail to meet the May deadline. I blamed filming for television, but in my heart-of-hearts I knew there was more to it than that. So I suppose I wasn’t entirely, that’s to say one-hundred per cent, honest. But not far off it. And all of what I did say was completely true.

Anyhow, I’ve written it many times in print, but I’m no good at assembling text-books. I can’t survey the available literature, analyse the various trends, then come to a balanced consensus about what’s happening. I’m a lousy critic. I think it’s because I’m too partisan: I always take sides and follow causes. So although I’m hopeless when it comes to distilling a ‘balanced consensus’, I do think I’m quite good when it comes to telling stories, and following plots or arguments. And that was what was lacking with my new book for Penguin: there was no polemic; no argument – no plot. It was all description and (dare I say it?) lifeless description, at that. The words on the pages sat there, like fat diners in a greasy spoon. They didn’t leap off the paper with a life of their own – which is something I look for in a book. Like with good mustard or horseradish sauce, there should be a hint of fire, even of danger, on the page. But sadly it wasn’t there. So I put it all to one side, as lambing was rapidly approaching and I knew I’d soon have plenty to occupy my time. But that doesn’t mean I let my mind turn off. That simply didn’t happen: somewhere in my sub-conscious a part of me was going over, and over, and over again, what I’d been trying to say – because by now I was fairly convinced there was more than just description behind what I’d just written. There was an idea there, but it lay hidden behind prolonged paragraphs of wordy description.

I made another attempt to return to the manuscript after lambing, in the early summer, when I had a few weeks off from filming. But again, the words weren’t flowing, like they normally do. So I decided that some serious thought was needed. Somehow I had to define, to release, that idea from the back of my mind.

Now I don’t know about you, but I find it’s hopeless to confront oneself directly. It never works. You can’t give yourself a good talking-to and come up with a new guiding principle for life. These things only happen when the time’s ripe for them. More to the point, I find they can be encouraged when one knows one’s sub-conscious is already on the job. Then it’s usually best to deliberately turn away and think about something else entirely. A Zen trick, I’m told. Which is what I did. Every morning I’d get up bright and early, and work on a fictional story I’d actually begun about a year previously, which (surprise, surprise) was all about an archaeologist who was trying to release something from the back of his mind. I did it purely and simply as a mental exercise and as a bit of fun, but it worked in two ways. First, it helped me realise what it was that I wanted my Penguin book to be about; and second, it took me the best part of another year to discover that the story had the makings of a book, too. But more about that shortly.

So what is the Penguin book about? I don’t want to give too much away at this stage, but essentially it’s about the way ordinary people have changed Britain (and indeed other countries). It is painted with a very broad chronological brush and most of the action takes place in prehistory, starting with the earliest re-settlement of Britain in the early Mesolithic period, at, or shortly after, 9000 BC. Incidentally, the rapid rise in post-glacial temperatures took place around 9600 BC. I address many issues and themes, but one of the things that has always fascinated me has been the extent to which Mesolithic hunter-gatherers managed (in effect ‘farmed’) their available resources. We now have accumulating evidence that they controlled the environment where their prey gathered, to make hunting more straightforward, but I also wondered to what extent they manipulated the plants that were major sources of gathered, and stored, food. And of these, one of the most important has to be the common hazel nut, the seeds of the native woodland shrub Corylus avellana. It must have been a major source of protein. Indeed, it’s almost impossible to open a report of an excavation at a Mesolithic, Neolithic or Bronze Age settlement site, without finding reference to quantities of burnt hazel nut shells. So they must have been important, but why were they burning them? As a student I’d been assured that this was part of the process of getting them ready for storage. So far as I’ve been able to make out, this was yet another example of a widely accepted ‘factoid’. But why burn them? As a boy I’d walked through the woods near our Hertfordshire home and had picked pocketfuls of hazel nuts, which I’d store in a shoe box in my secret den in a long-abandoned farm building. And they kept fine. Stayed fresh for weeks and weeks – and without any burning or heat treatment at all. So what was going on?

I pored over the literature, but could find very little of practical use, so decided there was nothing for it, but to do a small experiment myself. So that’s what I’ll be discussing in my next post – only this time I promise to get to the point rather quicker, and once there, I’ll stick to it. Meanwhile, blame Christmas. And so to my New Year’s Resolution: Make Digressions a Dream in Twenty Thirteen… Not exactly Wordsworth, but it’s the thought that counts.

December 21, 2012

Grow Your Own: Part 2, Digging

The world of vegetable gardening is, as they say in the press ‘sharply divided’ into two schools of thought: to dig, or not to dig. I’m a life-long digger and am not about to change, unless, that is, I hurt my back; only then will I forsake my trusty spade and fork. Now I’m not about to slag them off, because they do have soil science on their side, but non-diggers, too, take great pains to prepare their beds for the forthcoming growing season. So now, and the months of later autumn are when you want to clear away any perennial weeds such as couch grass (sometimes known as twitch), bind-weed, creeping thistles, creeping stinging nettles, ground elder and brambles. As I said in my last Grow Your Own, I’m personally not averse to using glyphosate (RoundUp), but only to beat these persistent problem weeds – and if your garden is afflicted by Mare’s Tail and Japanese Knotweed, then even glyphosate will have a struggle. If you have either of them, I’d go on-line and seek specialist advice, from people like the Royal Horticultural Society.

You want to get the digging done by the onset of the hardest air frosts, usually in early and mid-January. If you’re just starting a veg garden it might well pay you to borrow a Rotavator-style tiller and rough up the whole of your patch and then cover it with three to four inches of manure or compost, having first removed as many couch grass and creeping thistle runners and roots, as you can spot. You’ll soon get to learn how to identify bindweed and other roots. But whenever you see them, pull them out and put them on the bonfire. Never compost them! Having done that, let the worms and wet weather incorporate your spread of manure or compost into the soil over winter. If needs be, you can work it in with a fork, by hand. At least that way, you can start planting in all of your three or four zones, come springtime (I discussed crop-rotation in the previous Grow Your Own). Then start ‘proper’ digging, and in one zone only, next year.

So this is about ‘proper’ digging of the zone into which you will be planting potatoes and (much later) tomatoes. These plants are, of course, related (look at the flowers), natives of America, and are prone to blight and other long-term pests, including potato cyst eel-worm. So they must never be grown on the same patch of land two years running. But now to digging and let’s start with the organic material you are to dig in. You can often buy horse manure for about 50p a bag, as the horse owners are keen to get rid of it (and for some reason rarely seem to be gardeners – I think it’s something to do with having more money than sense. Whoops, a digression…). But remember, even horse manure needs to be well rotted: if it smells strongly of horse, rather than manure, it’s a sign that it’s still too fresh. By adding un-rotted manure to your land you will, in effect, be removing nitrates from your garden. So the rotting-down process effectively depletes the soil – which is why it should happen in the heap or bin.

The muck heap, showing well-rotted (two year-old) manure.

Compost should take a full year to be really well rotted-down, although some experts can do it much faster. The trick is to keep the heap or bin well aerated. I turn my muck heap over, using the front bucket of my aged tractor, but I’ve also done it by hand. The muck or compost should be crumbly and not too fibrous. It’s also a healthy sign if there are lots of small red worms in it. My chickens seem to peck away all the slugs and slug eggs, which is an advantage of keeping a few free-range birds around the place. Muck and compost heaps also attract the types of insects that swallows like and one of the pleasures of summer is to stand near the muck heap and watch while these most elegant of all birds swoop and twirl just a few feet above the ground. I could watch them for hours – especially the young birds who get passed tasty morsels, while still on the wing, by their parents and older siblings.

A general view of the patch to be dug, with brassicas front, right, heaps of manure and a small area already dug-over (foreground, by path)

I pile the well-rotted muck in long heaps on the ground to be dug. This helps drain it in a wet year, like this one. Then I dig it in with a spade or a heavy-duty garden fork. I’ve also taken to using a stainless steel spade, which sheds my heavy clay soil rather better than my old spades did. Make sure that the muck or compost goes well into the ground, then turn the spadeful of soil on top of it. Finally break up that clod of soil with a couple of chops – but don’t attempt to reduce it to crumbs, as that’s the job of the frost. If you reduce the soil to a fine tilth at this stage of the year, it’s likely to form a hard crust or ‘pan’ by springtime. So leave it rough and nature will do the rest. Finally, two words of caution: don’t work on, in driving rain or very wet conditions, as your feet will (a) regret it and (b) will puddle the ground surface and do long-term, structural damage to the soil. What you also don’t want to do is bury large lumps of frozen soil, which will take an eternity to unfreeze, come the spring. It’s a matter of common sense. Oh, and one absolutely final thing: don’t add any fertilizer to the ground at this stage. That can come later. At this time of year you should be more concerned with soil condition, than fertility – that’s for spring and summer.

Close-up of the dug-over area, showing the size of clods. My soil is now in quite good condition and naturally breaks down to clods this size. Fifteen years ago it was more stiff and clay-like, and turned over in large lumps, which had to be chopped-up with a spade.

This Time it’s Pink

Yesterday Twink was taking me for my morning walk through the woods when we came across this tasteful day-glow pink balloon, in the now familiar S-shape. No maker’s label and a bit weather-beaten. I honestly can’t be bothered to blog about each new balloon and if I did I’d lose all my followers, but I’ve included this one, just to show the problem continues – and nobody seems to think it matters. I forwarded my last post to the National Farmers’ Union (and we’ve been full members for over twenty years), but they didn’t even acknowledge receipt. Maybe if I’d been a barley baron complaining about Ramblers tramping through his grain plains they’d have deigned to reply…

But there are more weighty matters on the agenda – like the U.S. Fiscal Cliff. The more I think of it, the more I regard the Republicans as little short of barmy. Brain dead. Frankly, I’m lost for words that educated people in a sophisticated modern nation can be quite so stupid…

December 17, 2012

Bloody Balloons!

This morning dawned glorious. The sun rose above the black poplars as I cracked the top off my breakfast boiled egg – rather unusually two of our Cuckoo Marans are still laying this late in the year. Then, I washed-up and replete, and full of the joys of an English winter’s morning, I went for a stroll in the garden. All was well with the world. But then I saw something out of the corner of my eye, something glittery and red that clashed with the now rather fading berries of a Cockspur bush on the edge of the wood. I walked towards it, knowing full well what I’d find: yet another bloody helium balloon. This one was shaped like a vast letter ‘S’. I don’t know who or what that letter signifies, but as far as I’m concerned, Siegfried, Simon, Sharon or Samantha, you can fry in Hell. And I hope the turkey turns to slithery tripe in your mouth, as you tuck into your Christmas Dinner.

A distant view of the red balloon high in a tree

The red balloon at the top of a field maple tree

The red, S-shaped balloon

So what on earth is going on? Presumably they’re being released from Peterborough, Leicester or Birmingham, the big cities up-wind of the northern Fens. We’ve been finding one or two of these balloons every week since (I’d guess) August. Recently they’ve grown a bit larger – like that garish letter S. God knows how I’ll ever get it out of the field maple: the ground’s far too soft for a ladder, so I suppose I’ll just have to leave it there, looking ever-more faded, tattered and ghastly. But why is it that people in towns can dispatch aerial litter out into the country and not have to pay a fine? In fact it’s perfectly legal. I think these new larger helium balloons will probably claim the lives of several lambs next year, unless the government bans them. But what are the chances of that? This weak, ineffectual government (and that’s saying something after the last bunch of spineless nonentities!) will probably do what they did with ash die-back disease: commission a risk assessment and then sit on their hands. As a friend of mine once said: what a bunch of tossers; they couldn’t run a bath…

Anyhow, I took the photos you can see here, then accompanied my sheepdog Twink on her morning walk along the big drainage dyke that runs along the other side of the wood. And what should I see there? You’ve guessed it: yet another balloon. This time it was silver and shaped a bit like the letter ‘G’, although it had been in the dyke a few days, so was a rather tatty. But again, it was big – well over a metre long. This time it had a label that proclaimed proudly that it was made by Amscan International Ltd., of Milton Keynes, under the brand name Anagram. Well, damn you Amscan: why don’t you come here and clear up your bloody rubbish? I didn’t ask you to dump it on my land. And would you like me to send you a few dead lambs next March?

The label carried instructions that the balloon is not to be released out-of-doors as it might cause electric ‘power outages’. Yes, and lamb life ‘outages’ too. There’s also a danger of possible ‘entanglement injury’. You bet! Especially on the edges of a flooded dyke… But who in their right mind would release a vast balloon like that indoors? It’s a crazy idea, unless you happen to live in St Paul’s Cathedral or Buckingham Palace… But I suppose the formulaic warnings on that tiny label give useless DEFRA (which currently administers our rural affairs) an excuse to say that it has taken reasonable measures to warn the public.

The dyke round the back of our land: a typical Fenland view, but note the shiny balloon in the dyke near the camera

The silver balloon as I found it

The label on the silver balloon

And then, of course, there is the matter of the gas Helium, which is very much a finite resource – and quite rapidly being depleted. So are we doing anything to conserve it? Like Hell we are! This sort of thing makes one realise just how utterly powerless ordinary people are, in a modern world that is run by an uncaring breed of professional, and mostly urban, politicians from the snug sanctuary of the Westminster Village. Come back Guy Fawkes, all is forgiven…

December 14, 2012

Jack Frost and Other Old Friends

The past four or five days have been bitterly cold, with penetrating frosts and freezing fogs. The Fens have seemed positively hostile at times. And then the sun cuts through the mists and suddenly everything, and everyone, is transformed. That’s why I love this time of year. It’s the contrasts and the delight on people’s faces when the gloom lifts…

As a gardener I love the effects that hoar frost achieves on plants like the tall Molinia grasses which are now past their prime, but when touched by Jack Frost they gain new life, like elderly pensioners dancing to a Glenn Miller record. The older folk do it so much better than youngsters, even when dressed-up in the clothes of the nineteen- forties. I suppose it’s all about having lived the life and experienced the times – it’s not something you can act or, worse, re-enact.

Now that Time Team is finished as an eater-up of my time, I’m getting heavily involved with writing, which is what I really enjoy doing. More than that: it’s what I have to do. I know that might sound a bit pretentious, but it’s a fact, nonetheless. To be honest, it’s something I’ve only recently come to accept. For me, writing’s not so much an addiction, as a necessity. Like gardening, it’s something I’ve got to do. But I wonder, is it the same with bankers? Do they have to make money? But I think I’ll stop: maybe I detect the start of a digression.

Or do I? This writing business is strange. My current book for Penguin was commissioned over two years ago and the original deadline was the end of May, this year. But before that, I was asked to take a larger part in what we now know was the to be the final series of Time Team. As followers of this blog will know, I spent most of last summer whizzing around the country filming. And it should go without saying that filming and writing don’t go well together, unless, that is, the writing is the sort of work that doesn’t require deep research and reading – which is another way of saying the dreaded word ‘fiction’. Happily, my venture into this new field didn’t have to be a solo one, as I was accompanied by my old friend Alan Cadbury, who metaphorically held my hand throughout. I think you’ll be hearing more about our joint venture very soon. But to return to the subsidiary plot (and I’m getting much better at plotting, sub- and false-plotting in my old age), from September 2012 I was able to return to the writing of serious books, and that meant my current volume for Penguin.

Now if truth be told, yes, Time Team did interrupt my researches, but the actual writing hadn’t been going too well either, which is perhaps why Alan and the fiction came as such a welcome relief. I now realise the problem was a basic one: the new book lacked a driving theme, or any polemic. It was simply an account, a description, and as such it was lifeless: like some long dead text-book. Then I had the Big Idea. I’ll have more to say about that nearer the time of publication. If I mention it now the BBC will probably screen a mini-series on it, fronted by a grinning ‘personality’. So, sadly, mum’s the word – but rest assured it’s a corker and the words are now flowing.

Part of my research is into other people’s excavations, and I’m currently reading Mike Parker Pearson’s superb book on Stonehenge and the sites and landscape around it: Stonehenge: Exploring the Greatest Stone Age Mystery (Simon and Schuster, London, 2012). It’s a cracking good read and illustrates the extraordinary power of a modern archaeological project to get back to the roots of everything. It’s wonderful – and I’ve only got as far as Chapter 5. As I laid it down last night, my eye fell on an advert for Doctor Who and I thought about time travel – and is it such a great idea, after all? The trouble is, if you actually went back in time all you’d see would be a thin time-slice, and I don’t think you’d be much further forward. But what Mike and his team have revealed is how those great monuments on Salisbury Plain actually grew and developed. He has also put forward some very convincing ideas on why they were put there in the first place. I very much doubt whether Doctor Who, or one of his lovely young assistants, could even begin to offer such enlightenment. Like so many modern celebs and other heroes, they’re smugly content to skate over the surface: seeing much, but understanding so little.

Part of my research is into other people’s excavations, and I’m currently reading Mike Parker Pearson’s superb book on Stonehenge and the sites and landscape around it: Stonehenge: Exploring the Greatest Stone Age Mystery (Simon and Schuster, London, 2012). It’s a cracking good read and illustrates the extraordinary power of a modern archaeological project to get back to the roots of everything. It’s wonderful – and I’ve only got as far as Chapter 5. As I laid it down last night, my eye fell on an advert for Doctor Who and I thought about time travel – and is it such a great idea, after all? The trouble is, if you actually went back in time all you’d see would be a thin time-slice, and I don’t think you’d be much further forward. But what Mike and his team have revealed is how those great monuments on Salisbury Plain actually grew and developed. He has also put forward some very convincing ideas on why they were put there in the first place. I very much doubt whether Doctor Who, or one of his lovely young assistants, could even begin to offer such enlightenment. Like so many modern celebs and other heroes, they’re smugly content to skate over the surface: seeing much, but understanding so little.

I made several visits to Mike Parker Pearson’s digs near Stonehenge. This photo (taken in 2007) features Mike (right) showing a group of visitors the remains of a Neolithic house at Durrington Walls. We now know that this house was part of the largest known settlement of the period in north-west Europe.

Anyhow, as I said, I’m now in full-on writing mode, so I tend to get up very early (around 5.00 or 5.30 AM) and work till 8.00. I don’t always do silly things with tea-cosies (see the post: Hunting Disguises), but I do get to see some very beautiful frosty dawns, and yesterday morning’s was a stunner, as I hope these two photos make clear.

A general view of our garden shortly after dawn with a very heavy covering of hoar frost.

The view from downstairs along the small border, still too wet from the heavy rains of late November.

I close with this thought: why do so many people try to avoid the contrasts that life has to offer? Why escape the rigours of an English winter in favour of the sameness of a Spanish one? Part of the pleasure of an English summer is the thought that the lovely pond with yellow water lilies glinting on the surface was once a sheet of ice, where moorhens once strutted their stuff, like so many traffic wardens in an empty marketplace… Now I admit, that really is a digression.

December 7, 2012

Bonny Scotland

I’ve got a very soft spot for Scotland, and it’s not just that I like the people, the whisky and Rebus. It’s also got nothing to do with Maisie’s impeccable highland credentials. She hails from Moray, not far from John O’Groats and believe it or not she is actually descended from Jan de Groot, the Dutch ferry-master (he ferried passengers between mainland Scotland and the Orkney Islands) who daily risked his life traversing the Pentland Firth – one of the roughest stretches of water anywhere in the world. Jan established a hotel (perhaps lodgings would be a better description) for his passengers, and hence the name of the little settlement that grew up around it. Anyhow, an archivist at the nearby Castle of Mey (the late Queen Mother’s private residence) unearthed this fact. When she phoned Maisie with the news, she began the conversation with:

‘And would you care for the good or the bad news first, Mrs. Pryor?’

Impeccably polite the Scots.

‘The bad…’

‘I’m afraid I have to tell you your grand-father was illegitimate.’

Maisie already knew this – and anyhow wasn’t worried.

‘And the good news?’

‘There’s not a drop of Campbell blood in your veins.’

Which meant of course that her ancestors hadn’t taken part in the bloody massacre of Glencoe , when members of the Campbell clan were invited into the Macdonald stronghold and were treated to Highland Hospitality (no guesses as to what that entailed). The two clans were traditional rivals, but by tradition too, hostilities were always suspended during such gatherings. While the party was in full swing, some Campbell soldiers drew their swords and massacred about 40 of their hosts, driving the rest out onto the freezing hillsides. It was February 7th 1692 and it had to have been pre-meditated. And the perpetrators are still reviled. To this day people called Campbell can sometimes find rural highland hotels inexplicably fully booked up – even in the depths of winter. Old memories die hard.

But there was even better news to follow, because it turns out that one of Maisie’s ancestors was Donald Macdonald who survived the massacre. So I’m planning yet another trip to the highlands where I don’t expect to pay for anything… And that’s another myth about the Scots, which I detest: in my experience they’re generosity itself. And while I’m having a bit of a rant, why O why do some of my English friends get so upset about Scottish independence? Surely it’s entirely up to the Scots? If they want to break free of the United Kingdom, then that’s their decision. And the best of luck to them. One of my acquaintances even went so far as to suggest that the British taxpayer shouldn’t have bailed out the Royal Bank of Scotland, after (the ex – hooray!!) Sir Fred Goodwin’s excesses. Really? Surely it was the culture of the post ‘Big Bang’, free-for-all City of London, that was the real miscreant here. The culture of greed simply doesn’t accord with Scotland’s traditional Calvinistic principles. And besides, as a nation, they’re too canny for such stupidity, or indeed cupidity.

But, again, I digress: this post was meant to be about the fact that my book The Birth of Modern Britain is being put forward as the Current Archaeology Book of the Year. I was amazed, because for some reason my books never do well in such contests. Maybe it’s because I don’t write for archaeologists, or for students. I aim my books at an interested lay public whose next book is likely to be a thriller, or about gardening, dress-making or cookery. Even this time, all the other books up for the award are far more specialised; I suppose in some people’s eyes specialisation equals erudition, and hence quality. I wish life were that simple. In my experience, it takes three or four times as long to write a popular book as a heavy-duty academic monograph. For a start, if you’re doing something academic or specialized, you can use the jargon; and you never have to think about the general implications of what you’re saying. To give an example, The Flag Fen Basin: Archaeology and Environment of a Fenland Landscape, which English Heritage published in 2001 took me about two years to write and edit, whereas the very much smaller (a mere 250,000 words) The Making of the British Landscape took a generous five years. And I know, too, of which I’m most proud. It’s also interesting that the landscape book had very few reviews in the archaeological press and one or two of them were nasty-verging-on-libellous, written by prehistorians who thought I had deserted The True Faith. In the outside world, however, it was very favourably received, and by people of real stature: the likes of A.N. Wilson, Adam Nicolson, Clive Aslet, Paul Johnson and Margaret Drabble and in journals ranging from The Times and Guardian to the TLS and Country Life. So why is the little world of archaeology so often out-of-step with the outside world?

I wish I knew the answer to that question, but I suspect it’s got something to do with the subject’s appeal to some people, as a flight from reality: a snug, secluded world where the issues that concern its adherents aren’t things like global warming, the Arab Spring or world recession, but controversies over pottery styles, putative Iron Age invasions and the price of eggs in a Jacobean grocery. I think the trick to change all this will somehow inject more relevance into the topic. Although, God knows how it’ll be done: maybe a nuclear-powered enema? But why, despite the petty nonentities that still clutter its literature, does archaeology stubbornly remain relevant? I think it’s because it continues to tell us important things about ourselves and our times. In the words of the slogan at the masthead of the excellent magazine History Today: History Matters. Despite what some erstwhile colleagues might say, I’ll go on writing books that I hope one day might penetrate archaeology’s resilient armour of smugness. So if you believe in what I’m trying to achieve:

Click on the button at the top right hand corner of this blog. And think subversive thoughts, as you press on your mouse. Many thanks. Digression over.

So let’s end with something Scottish. For me Robert Adam’s classical designs have a restrained charm all of their own and one of my favourites is the bridge he designed across the River Tay, at Aberfeldy (Perth and Kinross), in 1733. It’s featured in the Birth of Modern Britain as a colour plate. And I love it. After I’d taken the photo, we sat down on a bench in the park nearby and Maisie produced a home-made packed lunch and a bottle of Speyside malt whisky. Then she drove us back to our lodgings. Bliss! To be ferried home by a direct descendant of John O’Groats himself…

General Wade’s bridge at Aberfeldy, Perth and Kinross, built in 1733, as part of his scheme to improve the Highland road network. It was designed by Robert Adam. This is a more distant view than the one in The Making of Modern Britain and shows the general layout of the bridge better.

Creating Fort Knox, a.k.a. My Vegetable Garden

One morning bright and early during the winter before last, I was heading towards the barn to release the chickens, and check for eggs. Overnight there had been a sharp frost, so I decided to take the gravel path along the edge of the vegetable garden, to avoid damaging the frozen lawn. The previous evening I’d covered the sprouts, winter cabbages and broccoli with fleece to help them survive the forecast frost, but as I approached them I could see instantly something was wrong: the fleece was torn and dragged to one side and the poor brassicas beneath, looked like they’d been hit by a tractor-mounted, heavy-duty flail cutter. Plants that had once stood three to four feet high, were now little stumps. Others had been broken and trodden into the ground. In the end I think a couple of purple sprouting broccoli plants survived the onslaught. But that was all. The rest – no less than six rows – had been trashed. Dropping and hoof-prints covered the ground and the shattered remnants of plants. I showed the scene of devastation to a farming friend, who just happened to drop by, and he reckoned there’d been at least half a dozen deer there. Muntjac deer. I’d heard them barking in the wood surrounding our garden, on several nights previously, and should have done something about it earlier. More fool me.

Mindful of the Muntjac, at the start of last winter we erected a temporary defence of cattle hurdles and stock-wire around the winter brassicas. It was effective, in that it kept the deer off, but was difficult to enter and looked, frankly, bloody awful. It also meant that I planted the brassicas far too close together, and as a result, the sprout crop was tiny and the winter cabbages grew no larger than apples. So the temporary defences were only a semi-success.

Last summer, while I was away filming with Time Team, we had two wrought-iron gates made-up and installed. These were more ‘garden-esque’ and looked quite pleasing when seen from the main garden. The other gate into the veg garden was off the yard, so it was plainer, and bought from a farming supply company. I installed it with a friend. All three sets of gates, however, would have been pointless without stout wire fencing between and around them. So that’s what I’ve been doing, during all daylight hours for the past four days. And this afternoon I finished – bloodied (wire always seems to draw blood if I’m around), but unbowed – and more than a little knackered. It was hard work: all the wire had to be pegged firmly to the ground, as Muntjac have short tusks and can lift fencing, and then wriggle their way under it. They can also jump up to five feet, so they’re redoubtable opponents. They’re also quite attractive as animals, but are very small as deer – no larger than Twink, my Border Collie. According to my Collins Guide to the Mammals of Britain and Europe, Muntjac (Muntiacus reevesi) are native to eastern China and were introduced to southern Britain in the 20th century, when they were imported to adorn the parks of country houses. Then they escaped, blast them – or rather the toffee-nosed, tweedy idiots, who shipped them over here for no good reason, other than vanity.

I’ve seen as many as three does together in our wood, but I gather they’re to be found everywhere in this Fen. The only consolation is that their meat is light and very well flavoured, and as they’re classed as vermin (which they are), a friend with a rifle and a hunter’s licence does his best to keep them under control for us. That means the freezer is usually well-stocked with venison – which we butcher ourselves. So does the free supply of meat make it all worthwhile? Most decidedly not, because Muntjac don’t just damage the vegetables, but the flower garden too, and coppiced hazel stools out in the wood never regrow properly, once the Muntjac have got their teeth into them.

I didn’t want the vegetable garden to look too much like a WW2 prisoner-of-war camp, so I’ve try to conceal stock-wire within hedges. This seems to work quite well and you don’t need to have such high wire, as they find it difficult to jump through a thick hedge. The hedges also conceal the vegetables from prowling deer. But there was no hiding the back gate from the yard, so that’s had the full Fort Knox treatment. Anyhow we’ll soon see whether all that work has been worth it. Now that that’s all out of the way, I plan to dig one of the four plots in the vegetable garden which I’ll cover in a post, hopefully in the near future, as part of my Grow Your Own series, aimed at those starting out on the vegetable gardening pilgrimage – which, rest assured, never, ever ends. It’s sad if a crop fails, or isn’t as good as you hoped, but it’s absolutely infuriating if it’s there one day, looking rich, tasty, and O-so-inviting – only to vanish overnight into the guts of animals who care so little that they poo all over their food. In fact that was the worst thing: washing the few miserable shrivelled sprouts that the deer couldn’t be bothered eat. Scavenging in my own garden. The sheer indignity of it! Grrrrrr!!!

The back gate into the vegetable garden, after the full Fort Knox treatment.

December 2, 2012

Samantha: a Suggestion

Today I was working in the barn, getting things ready for the ewes coming in after Christmas. Although the tractor was making a terrible din, I had an old radio turned on in the background. My sheepdog enjoys Radio 4, especially on Sunday, because she’s a huge fan of I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue. She’s particularly fond of the Chairman, Jack Dee, for some reason. Maybe she can detect the voice of authority there. I don’t know. Anyhow, I could see she was listening with particular attention, so I turned the tractor’s noisy engine off. It was the Chairman’s introduction and it came to the point where he says something a touch risqué about the fair Samantha. This week it wasn’t that funny and both Twink and I exchanged meaningful glances. You know how it is. Then it came to me: a truly smutty-verging-on-filthy introduction to the fair Samantha. It was one of those things, it came to me in one piece, whole, and positively throbbing.

Imagine Jack Dee’s doing his introductory spiel:

‘… and on my left hand sits the delicious Samantha…

Short pause, while audience chuckles knowingly. He continues:

‘And I think she has been treated harshly in the past. People don’t give her credit. She’s far from stupid. In fact I met a bloke the other day who said she knew lots about ornithology. He said they’d been out with a bunch of chaps in the marshes last week, and he swears she could spot a shag a mile away…’

END OF JOKE

Anyhow, I’ll allow the Beeb to use it, without my usual fee.

Francis Pryor's Blog

- Francis Pryor's profile

- 141 followers