Francis Pryor's Blog, page 23

February 2, 2013

Throw Off Your Winter Blues – It’s Glowing Willow Time!

This afternoon I was cutting back the jungle our front garden has become, after a summer where gardening was often impossible. I had my chainsaw on the go, chopping down dozens of five-year-old hawthorn seedlings that had colonised the Virginia rose hedge that runs along our drive. I’d been doing this for about half an hour and my back was starting to play up, as the seedlings had to be cut-off very close to the ground and that’s hard work, if you don’t want to catch the chain on the ground – which almost instantly blunts it. Anyhow, I straightened up and looked towards the north-east, where clouds from off the Wash were starting to look a bit threatening, when I could hardly believe my eyes. The willows, which look very spectacular with their bright orange bark at this time of year, were side-lit by the low February sun and the result – well judge for yourselves. I don’t think even Piccadilly Circus at midnight looks half so bright. We planted the trees from cuttings I nicked from a botanic garden (naughty me) thirty years ago. The willow is a garden variety of the native (I think) white willow, Salix alba, var. Kermesina.

If you do decide to get one, bear in mind they like it very wet and grow unbelievably fast and big. It’s not a tree for small gardens, unless kept ruthlessly cut-back. But if you can grow it, do, as it’s well worth it. An added bonus, if you grow them near water, are flocks of long-tailed tits – gorgeous little birds who make an enchanting chattering sound and have lovely delicate pink undersides. They’ve become a permanent feature of our garden, I’m delighted to say.

January 31, 2013

Time Team Series 20, My Fourth Episode: Coniston Copper Mines

The film to be shown this coming Sunday (February 3rd) at 4.20 (yes, that’s 1620 hours) was filmed high in the Cumbrian Fells, within the shadow of the Old Man of Coniston. We actually did the filming in the last week of July and it was that rarest of rare things last summer: a dry week – except for our small corner of Cumbria, where there was an isolated and stubborn area of low pressure, which meant it rained almost continuously. I’d get back to the hotel in Coniston in the evenings and speak to Maisie, who was busy supervising contractors making our hay. She was complaining about heat and dust, while I was frozen and drenched. Funny old place, England. Still, there are compensations: it was a record crop of hay and the quality was quite good. The sheep are munching it contentedly, as I write.

Looking down on Levers Water reservoir, with one of the Tudor period miners’ huts being excavated in the foreground.

Laying aside the weather, the site was very good. We were over a thousand feet up, overlooking a small reservoir known as Levers Water. The area had been mined for copper on and off, since the Middle Ages, but we were after evidence for the first intensive modern mines, which were dug and worked, not by the British, but by Germans. We tend to think that all early industry was led and developed by us Brits, but I’m afraid much of that is simply propaganda, because when it came to mining in the early 1500s, nobody could touch the Germans, who had the skills, the experienced workforce and viable companies, able to travel. In 1563 Daniel Hechestetter Senior, a master miner was approached by the Crown to operate new mines in the Coniston area, under the auspices of the newly established ‘Company of the Mines Royal’. That’s the basic history. Anyhow the mines prospered until the mid-17th century when cheaper Swedish copper began to take the upper hand. They then revived, massively, in the 19th century and it was these later workings that made our task so much harder. Almost everything we thought at first to be Elizabethan turned out to be Victorian. It was very frustrating. Then, by Day 3, we began to get the hang of things and made some remarkable discoveries – which you’ll have to watch the film to discover.

Good dateable finds were very hard to come by, as it would seem the early German miners tended to use leather or wooden domestic utensils – either that, or they were very, very tidy and rarely broke any glass or crockery. But on Day 3, good old Phil came down on a doorway threshold, roughly fashioned from oak. Anyhow, we sampled it for radiocarbon dating and got the result just before Christmas: 1490, plus or minus a bit. If we assume the wood was from a mature tree, then that’s pretty much spot-on. So the stone huts we were digging high above Levers Water do seem to have been genuinely Tudor – and probably German, too. It’s great when things pan out like that…

The Tudor miners’ hut was entirely filled with 19th century mine waste. This is a view from the outside, looking down onto the clay subsoil.

Inside the hut, we found a low hearth or fireplace let into one wall. This was probably used to melt small quantities of copper to test, or assay, its quality.

Further down the valley towards the town of Coniston, far below, was a second level of horizontal mine shafts. Some of these were Tudor. One (maybe early 18th century) can be seen immediately to the left of the falls, in the very centre of the picture.

Close to the stream, below the falls of the previous picture, the ground levelled out and here we found a high quality cobbled floor that almost certainly went with a dressing mill. This was where ore was further sorted and broken down into smaller pieces, to be taken down the valley to the main smelting furnaces, nearer Coniston.

January 27, 2013

Media Luvvies Are So Sad

I can’t believe it. Yesterday evening I attended the party to celebrate the end of Time Team and its twenty years of broadcasting history. And I make no apologies – it has been a wonderful success. As an archaeologist, if I’d mentioned in the local pub 21 years ago that I excavated prehistoric remains in England, people would have looked at me oddly: surely you should be doing that in Greece or Egypt? We don’t have such things here in England.

Then along came twenty years of Time Team.

Today, if I walk into a pub, and announce what I do for a living, the people at the bar ask me if I do geophys, or excavate. It never occurs to them to suggest I ought to be in Greece or Egypt. And that change in popular perception is entirely down to Time Team. So isn’t it truly pathetic that the channel that supported us for 20 years decided to push today’s Time Team back by an hour? Today’s programme wasn’t one of mine, so I’m not personally upset, but thanks to the brain-dead, imagination-deprived luvvies who now control so much of the media: I missed it. And so, I suspect, did hundreds of thousands of other loyal fans. WHAT A SHODDY WAY TO TREAT SUCH AN EPOCH-MAKING SERIES! I don’t know who you are in Channel 4‘s Presentation Department, but you should be ashamed of yourselves. Am I wrong, but do I detect a feeling that intelligent programmes shouldn’t be treated in this cavalier fashion, that art exists for its own sake and has a right to be treated seriously – as something worthwile and to be proud of? I don’t know how to create a Twitter or FaceBook storm (as I’m an old fart), but surely somebody needs to draw this to public attention. So tweet it, or shout it. But please do something!

Many thank x

P.S. I have just noticed that the programme is currently scheduled to be repeated tonight (28th January) at 1900 on 4seven, and again on 1st February at 0240 on Channel 4.

January 23, 2013

Grow Your Own: Part 3, Chitting Seed Potatoes

Outside the snow has been lying on the garden for at least a week. So yesterday I took the four-wheel-drive into the local town to buy seed potatoes. In the past I’ve bought them through catalogues, but these rarely guarantee delivery dates and I have received them as late as March, with long, pale shoots that snagged against the net bags and snapped off. That year my crop was late – and light. So now I buy them from a shop I can trust. I always go for Scottish seed, which is reliably disease-free, although this year the tubers themselves are quite small – which doubtless reflects the terrible, wet summer of 2012. The main reason I like to buy my seed potatoes this early in the year is that they’ve not yet had time to develop any growing shoots, a process known to gardeners as chitting. The young chits sprout from the potato’s eyes, or growing points and they do this as a response to growing day length and warmth. But they mustn’t, under any circumstances be frosted. The idea is to encourage the growth of tight, small, dark green (the look almost black) shoots and this is best achieved with plenty of light, but while they must never be frosted, they must also be kept cool – ideally below normal room temperature. So I put them on a sunny shelf in the porch. They will stay there throughout the rest of January, all February and most of March. If the weather isn’t too grim I like to plant my spuds before the end of March, but early April will do, if the long term forecast looks wet or frosty. Potatoes don’t like being planted in very cold soil.

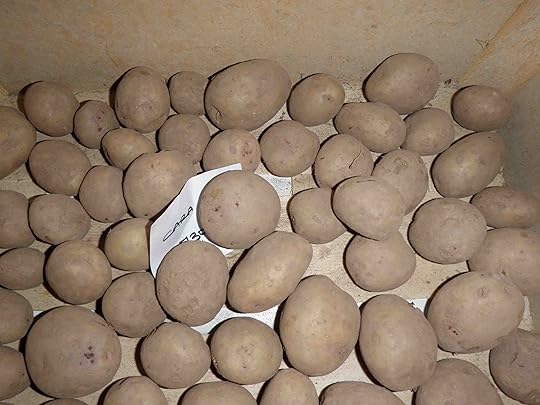

My 2013 Scottish seed potatoes: First and Second Earlies and Early Maincrop.

Seed potatoes are usually sold in net bags and one of the reasons I like to buy mine quite early is that the young chits easily snap off and catch on the bag’s netting, unless you’re very, very careful. Incidentally, I looked ‘chits’ and ‘chitting’ up in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary and the words derive from the Middle English chithe, meaning a shoot, sprout, seed or mote (in the eye). So there. Anyhow, buy your seed potatoes this time of year, and the chits won’t have developed. I then empty each bag into an old-fashioned wooden seed-tray, or an orange box (you can normally persuade farm shops or greengrocers to let you have them – but I very much doubt if supermarkets would oblige). Then make sure that you don’t mix-up the varieties and clearly label each box. I normally use two labels, as in the past I’ve had them removed by mice, or worse, blown away when I’m actually planting. That can be very frustrating. Check the seed carefully and chuck out any that look even slightly dodgy. Then spread them evenly across the bottom of the box or tray so that they all get plenty of light. Finally stack them, if you have to, so that they get plenty of light and air. As you can see from the close-up picture, the seed potatoes have no chits. They’ll be looking very different in late March.

The seed potatoes laid-out in wooden boxes and trays for chitting.

Close-up of Cara, the early maincrop variety I’ll be growing this season.

Now to varieties. There are five basic groups of potatoes: First Earlies, Second Earlies, Early Maincrop and Salad Potatoes. The first earlies include varieties such as Home Guard, Foremost and the one I’m growing this year, Ulster Prince. First Earlies, as their name suggests, are ready first and should be planted first (although I tend to plant everything thing at once, as that fits in with my other work on the farm). With luck you should be digging your first earlies in late May or June. But they don’t store very well and some people think that by July and August they’re starting to lose flavour. I don’t altogether agree. Second earlies come a bit later and are a superb potato if your soil is heavy, like mine. Heavy soils encourage slugs, which normally get very active after August, by which time your earlies and second earlies should have been lifted. But in very wet years (like 2012) they can succumb to blight and don’t store too well. Again, early maincrop varieties are ready before the autumn and are less heavily attacked by slugs. Maincrop varieties are best on chalky or sandy soils and they store longest – and ought to yield the heaviest crop, too. I grow Kestrel, a superb tasting, second early, and Cara, a pink-skinned maincrop developed from the old variety Desiree. Cara and Desiree are quite blight resistant and don’t seem to be too badly attacked by slugs. More important, they taste delicious and bake well (baked potatoes are a winter staple in our household). Salad potatoes in my experience are more trouble than they’re worth. The two commonest varieties are La Ratte and Pink Fir Apple. They eat well, even if they’re hard to peel when mature, as they’re very long and thin. But the main trouble is they also produce dozens of tiny tubers, which you can never recover when you’re doing the lifting. Those tiny tubers producers plants for years afterwards and will cause all sorts of problems with your crop rotation regime. So I steer clear of them; but other people swear by them. It’s up to you.

I always try to lift my potatoes in early August, even if the green tops (the haulm) haven’t died-off. If you lift them as early as this, let the lifted spuds dry-off for a couple of days somewhere sheltered, and that way they’ll develop tough skins; but don’t leave them in bright light for more than that, or they’ll start to turn green. Then bag them in light-proof paper sacks, somewhere cool and frost-free. I normally go through my stored potatoes and pull out any rotten ones in early December, before bringing them indoors, out of the way of harsh winter frosts. When they’re a bit warmer any rot will spread fast – so be ruthless. This year I threw about ten per cent out and it was well worth it, as I haven’t found a rotten spud since.

Some people say you shouldn’t bother to grow staples like potatoes and cabbages, but I strongly disagree. After all, what do you eat most of? So are they worth all the effort? You bet! Once you’ve got accustomed to proper garden potatoes, even the best bought organic spuds taste of very little – and as for the usual supermarket stuff, frankly I wouldn’t feed them to pigs. But then, I’m biased, because I also love a good joint of pork.

January 18, 2013

DIY Garden Decoration: Wirework

Maisie and I share one huge advantage over the bulk of middle class humanity: we don’t have good taste. Snobby friends from London are constantly having to avert their eyes as they walk around our garden: here’s a painted concrete gecko, there a hare – a real one? Sometimes, but we have one in concrete too, who stares up the trunk of a birch tree, at what I know not. Then there’s our shed-cum-summerhouse which we refer to as the tea hut – in reverential reference to the many leaky, drafty excavation tea huts we’ve both inhabited over the years. None of this is in Good Taste. The same goes for Maisie’s border planting, where pastel hues are often forsaken in her quest for something unusual. In our garden we don’t do tasteful ‘white borders’ or ‘yellow walks’. Yuck!

Similarly our garden decoration doesn’t yet feature coy, but big-bosomed bathing Grecian nymphs – the sort of thing that would set you back five hundred quid at an expensive garden centre. Although one day I’ll get one, and paint her livid gloss pink (with scarlet nipples), just so I could enjoy my smart London friends’ horrified embarrassment. No, on second thoughts, that’s just moved up my gardening agenda from ‘might do’ to ‘must have’.

So, being usually broke, we decided some time ago to do most of our garden decoration ourselves. Maisie even went on a course that taught her how to weave willow. The trouble is, willow rots after a few months, so she adapted her new-found skills to wire. And here are two of her latest creations. First, a cockerel, actually one of three, that was positioned on the top of nine-foot high fence post tripods. It looked fantastic when I snapped it on a recent morning, after heavy overnight hoar frost. The same frost did wonders to her two spiders’ webs, which serve as climbing frames for clematis under the pergola. I love those webs dearly and not just because our smart friends look at each other knowingly and raise their eyebrows just the tiniest, weaniest bit. But I always notice, and they simply can’t imagine the pleasure they’ve just given me.

Now where did I put that shiny gloss pink paint…

January 17, 2013

Time Team Series 20, episode 3, Henham Hall, Suffolk: a place with Latitude

Some readers of this blog may have been to the Latitude music festival, which is held every summer in the park of Henham Hall, near Southwold, just back from the Suffolk coast. I haven’t been to the festival myself, but I gather it’s one for connoisseurs – rather like the landscape in which it happens. Today it looks like a fairly standard 18th century landscaped country park, but in fact its history is far more interesting – and ancient – as this Sunday’s programme (Channel 4, January 20th, 5.25 pm) makes clear. It was a splendid and very enjoyable shoot (see Time Team Series 20. My Third Episode), and this was largely down to our genial and very welcoming host Hektor Rous – a member of the family that bought the estate, in 1545. I think most of the younger women on the shoot lost their hearts to him. Anyhow, I can’t discuss what we found, other than say there was lots of it – and most of it made sense. But here I want to consider some broader themes raised by the film.

Now I’ve long been fascinated by the destruction of so many great British country houses in the 20th century. I can sort of understand why medieval halls were torn down in the 18th century – they would have been seen as hopelessly old-fashioned by the new children of the Enlightenment. And when all is said and done it’s a toss-up whether I’d prefer a new Georgian or Queen Anne house to a medieval hall. On the whole I’d probably opt for the former – at which point all my medievalist friends will hiss ‘Bloody Philistine!’ into their gins-and-tonics. But the destruction that took place in the second half of the 20th century was extraordinary – largely because it was destruction for its own sake: in almost every instance nothing was built to replace what had been destroyed. The great W.G. Hoskins fulminated about it in the final chapter of his famous book, The Making of the English Landscape. But much of the seemingly wanton destruction was also motivated by some deeply felt social score-settling, for which I have much sympathy. The fact is, that before the last war, the English aristocracy and upper classes were unbelievably snobbish and elitist, and this made many people who hadn’t enjoyed their many advantages, very angry indeed. And to be quite frank, coming from a public school background myself, it has taken me the best part of a lifetime to realise just how profound their resentment must have been. Incidentally, for the benefit of non-British readers, the English so-called ‘public’ schools are anything but that: they’re incredibly expensive and highly elitist. Annoyingly, they’re also, generally speaking, very good as schools; usually far better than anything the state can provide.

So I do not think it’s good enough merely to sweep all this justifiable rage under the carpet with the patronising excuse that the people concerned had ‘chips on their shoulders’. Yes, they did – but they also had justification for their feelings of resentment, which comes across very well, I always think, in the wartime chapters of Brideshead Revisited (the book, not the TV films, which didn’t handle the underlying themes very well). As an archaeologist I tend to get annoyed, sometimes bloody furious, when I see wanton destruction of ancient buildings and other features in the landscape. Usually this rage is justified, because the people who are doing, or did, the demolition are motivated by the need to make money for themselves and their share-holders (see, for example, what I have to say about the wonderful ancient town of Kings Lynn, in The Making of the British Landscape). But sometimes one has to look a bit deeper below the surface. And of course it doesn’t help when the new building is actually rather better, or more original, than the one it replaced. For example, which would you rather: the old or the new St. Paul’s Cathedral? You could argue, of course, that what distinguishes Wren’s St. Paul’s from the cheap-and-nasty concrete buildings that replaced much of medieval Kings Lynn was the motive behind their construction. If so, then much of the post-war demolition of so many of Britain’s great country houses was understandable, if not always forgivable. In The Making of the British Landscape (Chapter 14), I tend to be more forgiving than censorious – and I’m fully aware that many people don’t share this view. But I still stand by it.

A recent book, which approaches the topic from the opposing, what I might term the ‘angry’ standpoint (and is none the worse for that), has used old photographs to illustrate the extent of the losses we suffered in post- and inter-war years. It is John Martin Robinson’s, Felling the Ancient Oaks: How England Lost its Great Country Estates (Aurum Press, London, 2011). I suppose the sub-title (with the words ‘Some of’ notably absent) states the author’s position, and although I found the tone of constant anger at times rather grating, it did give the book fire and energy that are so often lacking in lavish publications of this sort. I suspect it might melt many suburban coffee tables. Martin draws attention to the large number of buildings and estates that were torn down or sold-up in the inter-war years, when many families who had made their fortunes in Victorian and Edwardian times failed to adapt to the new, harsher economic realities that followed the Great War. I know I’ve mentioned it before, but if you want to visit one of the houses that was partially demolished then, try a visit to Witley Court next summer. The people at English Heritage are doing a superb job on the gardens.

We tend to forget just how good many Edwardian country houses and gardens could be, and for Christmas I bought Maisie a copy of Clive Aslet’s The Edwardian Country House: A Social and Architectural History (Frances Lincoln Publishers). It’s a superb book and it went down very well as a present. In fact I want to read it myself, when she’s finished. The illustrations are to die for, and the text is lively and informative. It’s far more than a coffee table book – and make one realise that e-books will never be able to completely replace the real thing. Now I wonder if I’ve just floated a hostage to fortune…

Meanwhile, back at Henham Hall Park, we were treated to no less than two separate episodes of demolition, both of which we had to investigate. And both of which had left standing traces in the modern landscape. The medieval hall survived quite well below ground and there was a single standing wall which surrounded the kitchen garden behind the house. Then the later house, built in the 1790s and demolished in 1953, has also bequeathed us a single standing wall, and the rest seem to have survived, below the turf. Even in damp seasons, like 2012, the course of its demolished walls can be seen as parch-marks in the grass.

Our first trench investigated the old hall. Notice the wall behind Tim Taylor (in the hat). This surrounded the original vegetable garden and was modified and re-modified through time. It took our buildings specialist several hours of close study to work out its entire sequence.

The splendid 18th century stable block. Very often it’s the stables that out-live the actual houses, as here at Henham

A standing wall – all that remains of the latest house built in the 1790s and designed by James Wyatt, it was demolished in 1953. Note the pale marks in the ground where buried walls show through the parched turf.

Places like Henham always have a few surprises up their tree-lined sleeves, and this time it was an ancient cork oak. The last one I’d seen had been as a teenager, when I spent a sweltering springtime near Seville. Sadly the future of those wonderful, and wildlife friendly, Spanish plantations is now in doubt, as corks have mostly been replaced by plastic stoppers and screw-tops – both horribly reliable and convenient. But one at least survives at Henham. Visit it, if you can, when you go to Latitude this year (July 18-21, 2013).

A cork oak in the park at Henham

Close up of the cork bark

January 13, 2013

Christmas Comes But Once a Year (and when it does, it’s late…)

Strange as it may seem, our lives don’t stop just because one of us is about to appear on millions of people’s television screens, prancing about in the rain somewhere in south Wales. No, sheep have to be fed and cake has to be eaten. Now I cannot pretend to be a traditionalist in the strict meaning of the term, but certain customs linger on in our lives, largely, I suspect, because we can’t be bothered do away with them. So they hang around, like an elderly dog or cat, not asking much and happy to receive the occasional pat on the head or scrap of turkey. And of course we’ve all been through the Festive Season, which still retains more than its fair share of rather creaky traditions, one of which is the ritual of starting the Christmas cake on Stir Up Sunday. The day gets its rather strange name from the Collect ordained in the Book of Common Prayer for the Twentieth Sunday after Trinity, which falls, I think, sometime in December (Trinity Sunday last year was on May 26th, so you can work it out for yourselves – then get a life). And it goes like this:

‘Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people; that they, plenteously bringing forth the fruit of good works, may of thee be plenteously rewarded.’

Wonderful stuff. And why has ‘plenteous’ slipped out of current use? It’s a splendid, sonorous word. All in all, I love the language of the Book of Common Prayer. The trouble is, it reminds me too strongly, still, of ghastly hours at school attending interminable services, when I’d much rather have been outside, in the sunshine. God, how I loathed chapel on Sunday. But I digress.

Stir Up Sunday was the traditional day you started to make your Christmas cake, subsequently you’d mix it again and add yet more rum and brandy. Then, in most households it would appear at teatime on Christmas Day, bedecked in tinsel and gleaming icing, to loud applause from everyone under thirteen. Teenagers would look bored (but stuff their faces when nobody was looking).

Anyhow, as we’ve grown older, we’ve both admitted that we don’t like marzipan, and that icing sugar is very, very fattening. So about ten years ago, Maisie started to dress our Christmas cakes with crystallized fruit. It’s quite a long job to do well, as each piece has to be glued down and then lightly glazed with syrup, so the job kept getting postponed until the next festival of our year, which is my birthday (January 13th). So that’s when we have our Christmas cake.

Maisie’s skills as a cake decorator have come a long way since one of her earlier efforts (2006) where the fruit are arranged in stiff rows, rather like the opposing armies at the start of the Battle of Waterloo. Now (2012) she is far more adventurous, with neatly cut and pasted flowers, that resemble a gastronomic mosaic more than a mere cake. I think we’re approaching High Art here. Mark my words, after this tour de force, Grayson Perry will start decorating cakes next…

So I’ll be munching that cake as my alter ego bustles around on the telly. But I know the film well already, so I’ll have the sound turned down and the Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain will be singing Teenage Dirt Bag. And then a glass of Cava (on special offer at our local Co-Op last week), followed by haggis, sprouts and bashed neaps. Merry Christmas!

The strictly regimented cake of January 2006

This year’s more stylistically assured offering

January 11, 2013

Time Team: The 20th Series, Second Episode: Rural Cardiff

Whaat? Rural Cardiff??? Yes, that’s what I said. And I’ll repeat: Rural Cardiff. We filmed last April and of course it rained. And rained. We’d just finished lambing, so I wasn’t particularly looking forward to what I’d been told would be an inner city shoot. OK, the site was an Iron Age hillfort, but it was positioned right on the edge of large housing estates and was, they said, one hundred per cent urban. Then I got there, and to be honest, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

We’d driven from the station through mile after mile of houses, under-passes, over-passes, roundabouts and all the signs of city life that I seem to spend most of my time trying to escape. Then we turned off the main road into a vast post-war housing estate, and to be honest our mud-spattered Land-Rover Defender looked a bit out of place. We turned into smaller streets, all lined with houses; past a couple of schools, then through a wooden field gate and onto a dirt road, down which flowed a small stream – it was raining hard by now. The driver engaged four-wheel-drive and we ground our way slowly along the narrow track. Eventually we got to the top of the steep hill where there was a fine ruined medieval church and an over-grown bramble hedge. It was extraordinary. As I said, I couldn’t believe my eyes. As we slowly stopped on a small strip of rough grass by the side of the track, the rain lifted. I even thought I caught a glimpse of the sun behind scudding clouds. Having been travelling for many hours by now, my old bones creaked a bit as I lowered myself to the ground from the back seats of the Defender. Mike Todd, the Time Team lead cameraman passed by with a cheery grin. Then I heard it: birdsong. And then some more. And some more: it was all around me. I almost expected strains of Ralph Vaughan Williams to waft lazily on the spring air from somewhere in the little church. It could not have been more idyllic.

In all my years with Time Team I have never seen such a stark contrast between town and country. We’d been told that parts of the nearby city – with the good old Fen name of Ely (island of eels) – were quite deprived and that we could expect trouble. But no. The stories were all wildly inaccurate. Yes, there was poverty – you’ll find that anywhere in Britain after the Bankers’ Bubble – but I detected no unpleasantness at all. Quite the opposite, in fact. People were plainly hugely proud of their hillfort in its gorgeous rural landscape, and they were over the moon that we were going to reveal a few of its secrets. Lots of people climbed the hill to visit the dig and I was constantly having to answer often quite difficult, and certainly well-informed, questions about the people who built and occupied the site. It made a great change to come across a community where Time Team was actually more about archaeology than its stars – the likes of Phil and Tony. And for what it’s worth, I think Phil and Tony appreciated that, too.

I also understand that the Time Team project will be the first part of what is intended to be a longer, more sustained, project to investigate the site. This will be organised in collaboration with Cardiff University and the local community. I wish them all the very best of luck. And I learned something myself on that dig. I had always known that people in Britain – and elsewhere – were proud of their origins and where they grew up, but I hadn’t been aware before just how specific that could be. Thinking about it in the train, on the way back home, I remember looking at the stately form of Peterborough’s massive Norman Cathedral – and having warm thoughts. Ely Cathedral – the Ship of the Fens – has the same effect, as do some of the buildings of Cambridge and that tiny Civil War chapel in Guyhirn, that I described in the last chapter of The Making of the British Landscape. For me, these buildings represent stability and the enduring value of the culture I grew up in. It’s very non-specific: I don’t believe in God, yet church buildings feature heavily in my memories. But in Ely, Cardiff I detected something else.

The view of Ely (foreground) and Cardiff from the ramparts of Caerau hillfort. One of the outer ramparts can just be see on the left.

The hillfort at Caerau dominates the surrounding housing estates and urban landscape, just as Arthur’s Seat dominates Edinburgh. I love Ian Rankin’s Rebus books, but to be honest I sometimes felt that the detective’s feelings towards the physical townscape of his native Edinburgh were, if anything, slightly exaggerated. But after my short stay in Cardiff, I must concede I was wrong. I think it must be the effect of large numbers of people living close by each other, but something had developed in the community that verged on reverence for that massive hill and its Iron Age fortifications. And the more I thought about it, the more I realised how right they were: how much better it is to revere and show respect for something of such enduring fascination and mystery. So very much better than the narrow sectarian beliefs that are tearing apart societies in the Middle East, north Africa and until very recently, Northern Ireland. So can archaeology and a sense of place one day play a role in healing such deep divisions? My experience of that particular community in Cardiff, suggests it might.

I don’t want to give away what we discovered, because if I say much at all it will spoil the film. But the hillfort was very well preserved and the geophys team surveyed all of the interior, which is richly scattered with houses, settlement and farm buildings. There’s also a surprisingly substantial Roman component to the site, too. The defences, the ramparts to give them their correct name, were cloaked in woodland, and I don’t think I have ever seen such a profusion of wild flowers: dog’s mercury, primroses, anemones, hedge garlic, bluebells – it was like walking through a nature reserve. No wonder the people of Ely were proud of their hillfort at Caerau; because it’s got everything: stunning archaeology, good finds preservation, wonderful woodland and wild flowers to die for. And all of this within comfortable walking distance of the capital of Wales. You couldn’t ask for more.

The hillfort’s defences were hidden deep in woodland. Phil is looking up towards the largest, inner rampart. Note the covering of wild flowers at his feet.

It was a very wet dig and the heavy soil at Caerau was very unforgiving. Here the team are finishing work on a small Iron Age ditch that sub-divided the hillfort’s interior.

Sometimes hillforts in Wales and the West produce very little by way of finds. This was probably because Iron Age communities in these regions preferred to use vessels and containers made from wood or basketry; but not at Caerau where the pottery, such as this earlier Iron Age jar, was well-made and in very good condition.

January 4, 2013

Hints of Spring

After the wettest year in England since records began, the new year kicked off with a dry, sunny January 1st. The next day it rained, but that one day of sunshine seemed to lift everyone’s spirits. Then yesterday Maisie noticed that the barometer hanging in the hall had leapt up from ‘Change’ to ‘VERY DRY’. Just before lunch the sun poked through and I decided to take my sheepdog Twink with me for a quick walk in the wood. It’s so sad: I can’t walk among those ranks of sturdy ash trees without thinking about their impending death. I wonder when it’ll happen? I’d guess in a couple of years’ time, as the disease is already in Norfolk, our neighbouring county. So sad. But enough of that: shoulders back and think cheerful thoughts.

The wood is changing every day. Snowdrops are now growing appreciably, and in the last couple of weeks, Hellebores have come into flower. A few years ago we bought a plant of the garden variety of the native Hellebore, H. foetidus, var. Wester Flisk and every so often a seedling (probably a cross with the straight H. foetidus) springs up with the red veined leaves of Wester Flisk (which itself was a sport). Rather more common in the wood than the native Hellebore, which seems a bit reluctant to thrive in our heavy soils, is the European Hellebore, H. orientalis whose hybrids are now forming quite substantial patches. I think its flowers look almost better when they’re just about to open – although, having said that, when they do flower they look gorgeous, especially when poking through snow on a sunny February day.

Helleborus foetidus

The big surprise when Twink took me towards a pair of big oaks, was a hazel bush whose catkins had opened for the first time this morning. I’ll swear they weren’t open when Twink led me along the same route yesterday (later I discovered why she was so keen to come this way: a very dead hare).

The first hazel catkins

Then finally, we came across several patches of aconites that had just pushed their heads and leaves up through the silty muds stirred-up by the endless rain. If ever there was a sign of spring, it was those aconites. So I’m beginning to think there’s hope in sight. Let’s all pray the rain holds off for a few more days – or even weeks. It would be lovely to be able to go for a walk without wellies and squelching. Of course, I suppose I could always lay a tarmac path through the wood. Then it would be just like Wisley or Kew. But what else can they do? We really do pay a huge price for living in such a crowded island…

Aconites

January 2, 2013

Time Team: The 20th Series Starts next Sunday – And We’re Going Down with a Pang … or should that be BANG!

The first episode of the 20th, and last, Time Team series is going to be screened next Sunday, January 6th at 5.25 on Channel 4. As is the usual practice of broadcasters, they’re going to be showing the best one first – that way, you catch as many viewers as possible. As far as I was concerned last year, the film we’re all going to see next Sunday was my last episode; we filmed it in the late summer and then we all went our separate ways, some of us nursing slightly thick heads after the Wrap Party, just outside King’s Lynn. In fact, it wasn’t just my last episode, it was THE last episode. And did we go out with a bang!

If you want to see what I wrote at the time, look at the four posts I did back in August, under the heading ‘Time Team Series 20, My Sixth Episode’. But as you’ll discover shortly, they only told half the real story. Now I don’t want to give anything away, but this was a most remarkable shoot – in my mind it’s up there with the really good ones: the navvy camp at Risehill, in Yorkshire, the strange skull-duggery at Llygadwy, in south Wales and that remarkable dig behind the German lines on the 60th anniversary of D-Day. Gateholm was good, if under-realised, and at least two others from the 20th Series were up there with the great ones – including that remarkable investigation of the WW1 Machine Gun Corps training camp at Belton House, near Grantham; but it was a great shame the channel screened it so early on Remembrance Sunday afternoon/evening: everyone I’ve since spoken to managed to miss it (including myself!).

The view from the Roman fort today. In Roman times the sea would have lapped a few yards from the camera; this was where the stones used in the fort would have been unloaded. Today the coastline has moved just beyond the buildings on the horizon.

To be honest, I was rather daunted by the task that confronted us: for a start, Roman military archaeology is unbelievably complex and being a mere prehistorian, I knew it could easily be a mess-up, unless I listened carefully to what the many experts around me were saying. Fortunately, David Gurney, the County Archaeologist for Norfolk, was the main expert and he and I had worked closely together in the very early days of Flag Fen – in fact he was a part of the small team (six of us, I think) who did the initial dig there, back in 1982. A small select band, if ever there was one. So I had good advice, but I also knew that we had been given a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and we had to make something of it.

But there was something else, too. The site in question was a Scheduled Ancient Monument, which meant that it was protected by Act of Parliament. Scheduling, as it’s known, doesn’t mean that archaeologists cannot do anything, but it does mean that whatever they do must have specific, clearly defined, aims, which must be approved by English Heritage – the site’s guardians, as set out by Parliament. So our research objectives were all about understanding the site better, in order to assure its survival into the future. Put another way, you can’t protect something if you don’t know what it is, or was. And as this is the 21st century, the various research themes, plus the detailed methods we used to achieve them, were all written down and agreed, in a document known as a Scheduled Monuments Consent form. I was the designated Archaeological Director, and at the bottom of this document was my signature. So if things went wrong, and we didn’t do what we said we’d do, I’d be the one banged up for life in the Tower of London, or Dartmoor. Worse still, my reputation would be in tatters.

Anyhow, the dig started and it went very well. But while trenches were being opened, John Gator and his merry men (and women) were carrying out an extraordinary rapid and detailed geophysical survey. By now readers will know that I’m a huge fan of John and his small team, but this time they were to excel themselves. Now again, I can’t say what it was they revealed towards the end of Day 2, but believe me it was astonishing. Mind-blowing, in fact.

Meanwhile, Phil and his group in the main trench were digging ever-deeper and finding extraordinary stuff as they worked. But apart from the initial stripping of the topsoil (which had been disturbed earlier in the last century by shallow ploughing), our Scheduled Monuments Consent agreement specifically forbade us from digging any archaeological feature with a machine. And just as well they did, or we’d have missed some extraordinary finds – but again, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait for the film to see what they were. What made these finds remarkable was that they were all Roman – and military – but were found amongst stone rubble that had once formed the core of massive stone walls. These had collapsed in the 18th and 19th centuries when the nicely-dressed masonry blocks were removed to be used in houses and farm buildings. Bear in mind that this part of Norfolk doesn’t have good building stone; so it made sense for locals to pinch the stuff brought here in the late third and fourth centuries AD, by ships employed by the Roman Army. You can still spot Roman masonry today in some older buildings round about the fort.

Phil Harding stands beside his trench on Day 2. By the end of day 3 it was over a metre deeper in places. Note the labelled wheelbarrow full of finds (and for a close-up of those finds see my earlier post: Time Team Series 20, My Sixth Episode: Afterthoughts).

Late in the afternoon of Day 2, it was suggested that the next day we should open a new trench to investigate the discoveries made by geophys. Originally a five-metre square was proposed – which I vetoed out-of-hand. I didn’t agree with what was being proposed, but then I didn’t say no, either. I suppose it was weak or indecisive of me, but in fairness to myself, I was under a huge amount of pressure to say Yes – and in my heart-of-hearts I was aware we shouldn’t. The thing is, we knew by then that the undisturbed Roman levels could only be reached by digging through over a metre of rubble. And we had one day in which to do it. By hand. So a three by five metre trench was suggested. Again, I dithered, but was aware from later conversation that evening, that I’d given the impression I’d agreed. But I hadn’t. Bloody Hell! Talk about the horns of a dilemma…

I retreated to my room early and watched something mindless on telly. That night I lay awake. I simply couldn’t sleep. I knew that at some point tomorrow morning someone would suggest that we should take a machine to the new trench, and although I hoped English Heritage wouldn’t agree, we’re all human, and those geophys results were absolutely superb…

Eventually, I drifted off to sleep, but awoke with a bang around four in the morning. While I’d been dreaming, my sub-conscious had worked out that even the smaller trench they’d proposed would involve the hand-removal of a minimum of fifteen tonnes of material. That was crazy! Even with a digger, you’d be hard pressed to do it with any care at all – and anyhow, I doubted if the big machine could work with stone rubble in such a small trench. And the sides would be bound to collapse. No, the more I thought about it, the more the idea seemed, to put it politely, misguided.

I got up early for breakfast. As usual Phil was there – like me he’s an early riser. He pleaded with me not to transfer him out of his trench, which his team were just getting to grips with. He was aware that the plan had been to put him in charge of the new, ‘star’ trench. That did it for me. I was now in no doubt what I had to do: at last, the worm had turned. Whatever else might happen that day, the new trench wasn’t going in. End of. So I delivered an ultimatum, and thank heavens, the-powers-that-be saw sense. Eventually everyone, even the proponents and supporters of the new trench, agreed that we’d made the correct decision, but I have to admit my last day ever on a Time Team excavation was (how shall I put it?) tense. To be honest, it took the edge off my appreciation and enjoyment of the excavation. Anyhow, I can confess now, that at the Wrap Party, that evening, I drank far too much.

I saw the final edit of the film a few weeks ago and sadly, I don’t think any of that behind-the-scenes tension came across; instead, everything seems as usual: loads of enthusiasm and get-up-and-go. And of course fabulous finds and archaeology. But believe me, on that particular occasion it was rather different, and you could have cut the atmosphere on the morning of Day 3 with a knife. Oh yes, come to think of it: it would have made a cracking real reality television film…

Francis Pryor's Blog

- Francis Pryor's profile

- 141 followers