Francis Pryor's Blog, page 18

December 19, 2013

The First Road Atlas and a Real Life Detective Story

I have to confess I have never been a very club-able person. If I’m asked to join any organisation I tend to shy away. And why? I guess it’s because I’ve found that organised groups tend to ask more than they give, so you end up serving them, rather than the other way around. That’s fine if the group concerned is a charity, but often it isn’t. And hence my reluctance to get involved. But I have discovered one or two notable exceptions to this rule, and one of them is my crowdfunded publisher, Unbound.

Each book that Unbound publishes will involve different costs and expenses. Put simply, some are longer than others and will contain more pictures and maps, which soon add to the overall sum that’s needed to be funded by subscribers. Books like my crime/thriller The Lifers Club have no pictures and are therefore quite cheap to produce, and that’s why we reached our target in five months (A QUICK PERSONAL PLUG: but don’t worry, you can still subscribe and get your name printed in the book for Christmas!). Incidentally, all my subscribers will receive their copies in early May.

While I was in the middle stages of my subscription campaign I received a lot of help and advice from other Unbound authors, like Adrian Teal. And that’s what I’m doing now, and no you cynic, not for myself, but for another Unbound author, Alan Ereira, as his book is facing a huge subscription target. And why? Because it’s got a lot of very, very intriguing things to say, and being non-fiction, it will be packed with maps and illustrations.

Alan is a distinguished maker of films for television and has already done a small documentary series on the project with Terry Jones (another Unbound author) for BBC Wales. So, much of the research has been done already, and the story has, as they say in the media, ‘legs’. Put another way it’s real and not at all flaky, which might seem odd when I describe what it’s all about. And I’m not alone in this view, the distinguished historian Professor Ronald Hutton, of Bristol University, agrees with me. So what is it all about?

The Nine Lives of John Ogilby is about the turbulent, pioneering and creative world of late 17th Century Britain. As Adam Nicolson’s superb recent television series so clearly demonstrated, this was when the modern world took shape: science began to replace dogma and superstition and the English Civil War had just given rise to the world’s first constitutional monarch, Charles II. If I could be transported back to any time other than the later Neolithic or Bronze Age, it would be then, the turbulent decades around the Restoration of 1660.

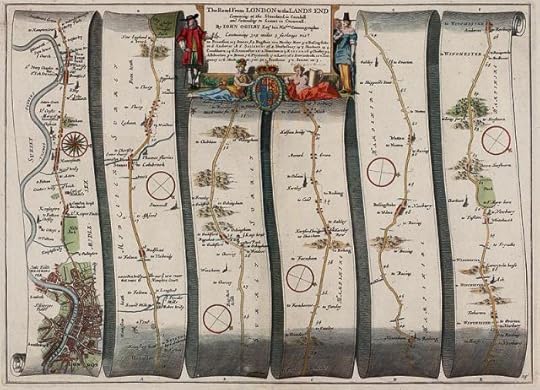

It was a time of astonishingly high achievers. We all know about the likes of Newton and Wren, but were you aware that the world’s first road atlas, the forerunner of those books that used to be found in the glove compartment of every car in Britain, was written and published in 1675? Do you have fond memories of those days when people still knew how to read maps, before the dreaded Sat Nav effectively removed all knowledge and appreciation of the places and landscapes we were driving through? Well, if you do still look back on those times warmly, as I do, then spare a thought for poor John Ogilby who started it all, when in his 70s he helped survey 20,000 miles of routes, as he wrote and published his great work, Britannia; it’s a masterwork, where for the very first time roads are treated as entities in their own right.

This example reminds me of those sections at the back of most road atlases where motorways are mapped-out to reveal the complexity of their junctions and intersections.

This map, taken from John Ogilby’s Britannia (1675) shows part of the road from London to Lands End in Cornwall.

To be frank, I’d subscribe to The Nine Lives of John Ogilby if it was just about the road atlas. But there is another story lurking just below the surface, and again, this seems to be fact, not fiction. I don’t want to give away the fascinating story that Alan told me last week, but in the 17th century things were not always quite as they seemed. The complacency that became such a part of fashionable circles in the later 18th and 19th Centuries had not set in. Even a genius like Newton, who understood more about the universe than any man alive, was still able to maintain an active interest in something as seemingly barmy, to us today, as alchemy. The arrival of the modern world was so recent that its grip on people’s consciousness was still far from complete. In fact that’s one of the aspects of this project that fascinates me. In a strange way it was rather like our own time, where people of my generation (and I was born in the closing months of the last war, in January 1945), and even younger, are having trouble adapting to, and coping with, the new digital environment. I reckon, rather like the new world that followed on the Glorious Revolution of 1688, it’ll take another three or four generations before the changes become fully embedded within society as a whole. And that’s one of the things I like about good history or archaeology: it makes you look with new eyes on your own life and times.

The title page illustration from John Ogilby’s Britannia (1675).

If the story of the world’s first road atlas wasn’t enough of itself, Alan has also discovered that Britannia contains some extraordinary clues about a much broader political conspiracy. For a start, the roads Ogilby selected for detailed analysis aren’t the obvious choices – everything that radiates out from London. There’s a big bias too in favour of Wales and the west country. There are also some intriguing hints in the illustration on the title page: why the all-absorbing interest in the sea in the background? And who are those figures on the roof – and the statutes in the niches? If one didn’t know what the book was about, I have to say I’d even wonder whether the scene was of a landscape in Britain at all… Or is my imagination getting carried away?

As I write, Alan Ereira’s project is 28% subscribed, but he already has some very generous subscriptions to his credit. I think it’s such a fascinating story that once word gets out, the names will start rolling in – and I’m proud to say that mine is up there with them. So please, join me if you can and give Alan and John Ogilby a Merry Christmas. And remember, the more you subscribe, the quicker it’ll be published. And if you happen to be a rich banker at a loss what to do with your New Year bonus, the paltry sum of £2,500 will buy you a weekend in Wales on the road to Aberystwyth, with the author, tramping ‘the most beautiful road in Britain’ and one that Ogilby mapped in extraordinary detail all those centuries ago. And how much healthier that would be than quaffing Champagne in industrial quantities at some trendy City bar! Myself, I settled for the hardback at £20.00, but then I always was a tight bugger. Anyhow, this is where you go to subscribe:

http://unbound.co.uk/books/the-nine-lives-of-john-ogilby

December 12, 2013

My offering for the archaeology blogging festival.

For many years I used to be a member of the Society for American Archaeology, largely because I found its journal, American Antiquity a constant source of ideas and enlightenment. Eventually my groaning bookshelves couldn’t cope any longer, so reluctantly I dropped my subscription. The SAA was founded in 1934, a year before its British equivalent, The Prehistoric Society, and today has an astonishing 7,000 members. Its Annual Meeting is a huge event, more like a road show than a learned society convention, and when I worked in Canada in the 1970s I managed to go to a couple of them, one of which was in Toronto, the home of The Royal Ontario Museum, where I worked as an Assistant Curator. In 2014 it will be held in Austin Texas on April 23-27 (check it out at saa.org). In 2014 the Annual Meeting will also involve a Blogging Festival and I have been asked by the festival organiser to submit a short piece, based around the theme the Good, the Bad and the Ugly in archaeological blogging. Anyhow, for better or for worse, this is what I wrote.

Spaghetti Blogging

Francis Pryor

Rule One: avoid clever titles, unless they’re funny. Rule Two: stick to the point. Rule Three: eschew obfuscation (avoid lack of clarity). Rule Four: don’t patronise with obvious explanations. Rule Five: don’t lay down the law. Follow these rules and you’ll be a good blogger; ignore them and you’ll become a Professor before you’re thirty.

Now I want to have a brief rant. Academic archaeological writing is ponderous, wordy and inelegant. It flows with all the suppleness of a disintegrating iceberg. Style doesn’t seem to matter anymore. It’s as if the writer expects his or her readers to experience pain rather than pleasure while they are acquiring new knowledge. Now I don’t expect archaeologists to compose mellifluous prose à la Jane Austen or F. Scott Fitzgerald, but please, at least make a small effort: try to avoid constant repetition of the same words. And do you always have to be quite so laboriously Politically Correct? I am well aware of the difference between gender and sex, but do I have to have it shoved down my throat (so to speak) every time I open an article, note or paper on anything that touches on human inter-relationships? I wouldn’t mind if it wasn’t for the fact that these papers are so dreadfully written; they’re also invariably humourless. The trouble is, the content gets forgotten or ignored because its delivery is so flawed.

The trouble is, too, that bad writing so often conceals woolly thinking, or half thought-through ideas – which are, by definition, impossible to express clearly. I’m absolutely convinced that much of the career-enhancing theoretical rubbish that was written in the ‘80s and 90s about top-down hierarchical societies, led by Big Men, who exchanged Symbols of Power, was only made possible through high-flown, verbose academic language. That, and mutual back-scratching on a huge scale. Had these concepts been described in plain English we would all have seen through them. As it was, I kept my head down and scraped away with my trowel, hoping to find the palace of the Big Man who built the local equivalent of Stonehenge. But of course it never happened, because neither he nor his swanky home had ever existed. It was all academic clap-trap.

I dearly wish there had been some blogs around in those days, because I am convinced they would have burst the bubble much, much earlier. The trouble was that academics only spoke to other academics. I can remember trying to persuade colleagues that Bronze Age fields with entrances at the corners had been laid-out with livestock (usually sheep or cattle) in mind. Any working farmer would recognise the pattern immediately; indeed, medieval market places were invariably arranged with corner entrances. Despite this, my suggestion was usually greeted with rather patronising, non-committal smiles, as if to say: who does he think he is? Sadly a recent conference on ancient farming did not feature a single farmer. Just academics.

In the 1960s and ‘70s Processualists taught us that archaeology was a science and that therefore photographs must be dull, colourless and ‘objective’, and all with over-prominent scales. Anything that attempted to convey mood, atmosphere or landscape was completely out. And didn’t those dreary photos that defaced so many excavation reports, send you to sleep? Oh, and while I’m on the subject, why do writers of academic archaeology feel it essential to dispense with all punctuation

I only joined the blogging community at the start of 2012 and I have to confess I find it addictive. I used to keep a diary, but that has now been taken-over by the blog. And why do I like it? For a start, I’m one of those people who has to write. I know that sounds pretentious, but it’s a fact, nonetheless. Given that relatively harmless addiction, it’s good to have a readily available outlet and one, too, that uses the photos I generate all the time – and again, photography’s another minor addiction, although I will never be half as good as Bill Bevan, at Sheffield University, whose pictures in Walk into Prehistory (Frances Lincoln, London, 2011) are simply breath-taking. My blog may not be great Art or Thought and it won’t bring me academic advancement (and anyhow, I’m too old and past it, for that), but I hope it’ll bring archaeology to a wider audience, because I also write about some of the other things in my life, like the sheep, the garden, the crime books and of course, the occasional intemperate rant. And a useful tip: my brother-in-law checks my scripts and filters out words like ‘slimeburgers’ in case litigious commercial caterers decide to prosecute (which I gather they do at the drop of a hat). For what it’s worth, too, I also Tweet (@pryorfrancis) to help build-up my blog’s followers.

So I see my blog as a way of uniting life and archaeology. I try to write in plain English and I’m delighted to see that other bloggers are doing the same. I also try to use good photos, and again, other bloggers take good artistic pictures, too. OK, so far our efforts are still at the individual level, but does that matter? I think not. Indeed, if anything, it’s a strength, as corporate blogs can be a yawn. If the internet has anything to teach, it is that that movements can build and grow from the bottom-up. You don’t need to go viral to have a huge and long-lasting effect. If enough people start to blog about archaeology and then gradually broaden their scope, maybe our subject will become less theory-obsessed and more relevant to modern life. Why do so many archaeologists choose to ignore sources of information and inspiration that are born of people’s experience of ordinary life? If they blogged they’d soon realise the error of their ways.

I see the current small, but growing, community of archaeological bloggers as so many militant moles who are mining away at the foundations of those loathsome ivory towers that were erected in the ‘50s and 60s to keep our fascinating subject above and beyond the aspirations of ordinary people. Who knows, but with luck we’ll soon bring them crashing to the ground.

November 30, 2013

HOORAY!!! At Long Last we are Going to have Prehistory on the National Curriculum!!!

Now admittedly it isn’t until next year and it’s for primary not secondary school children (and one might legitimately suppose the subject might be better understood by slightly older children), but – and it is a whopping BUT – the people who administer the National Curriculum have actually done something original and positive. And I know it has taken an eternity, but even so, let’s not grumble. Instead, let’s rejoice. And can I make a plea to any professional prehistorians who might be reading this (and especially if you are lucky enough to have children at primary school yourselves), have a word with the teachers at your local school and offer them any help or advice you can. Remember, things that we take for granted, like a handful of waste flakes or some scraps of animal bone from off the site spoil heap, could fire a child’s imagination. We’ve absolutely got to make the most of this new opportunity. We mustn’t let it pass by.

Anyhow, I’ve been trying to help in my own small way, too, and wrote the following piece for a splendid educational blog http://schoolsprehistory.wordpress.com. The direct link to my piece is:

This is what I wrote:

Why Prehistory Matters for Kids

We all need a sense of perspective if our lives are ever to make any sense. When I was very young I adored dinosaurs and made models of them. By the time I was a teenager that sense of the distant past began to expand, but I could find very little that filled the huge gap – a mere 100 million years, or so – between the Jurassic and our own time, because history began, with a respectful clunk, in 5th century BC Greece. There may have been a mention of the Mycenaeans there somewhere, but certainly there was nothing about Britain, which may as well not have existed. It wasn’t until my university ‘gap’ year that I realised just how advanced British Neolithic culture actually was – and what we know now has truly transformed things, to such an extent, that I would have no hesitation in saying that Britain from about 4000 BC was effectively civilised. Indeed, I would see the birth of modern Britain at around 1500 BC, mid-way through the Bronze Age. By that time the British Isles were cleared of most forest cover; there were field systems and settlements and these were linked together with a national road network, plus a host of local lanes and trackways. There would have been regular crossings of the Channel and North Sea and people living along the Atlantic coastal approaches were in constant touch with communities further north, in Orkney, Shetland and Scandinavia, not to mention the Atlantic shores of France, Spain and Portugal. By the Iron Age Britain had developed its own artistic style, known as Celtic Art, which has a liveliness and robust vigour that still speaks to us, 2300 years later. Indeed, I have heard it said that Celtic Art was Britain’s only original contribution to world art (but that’s a bit hard on the likes of Turner, Constable and Moore). Yet until now this rich story has been ignored by schools and educationalists.

I believe passionately that we’ll only avoid making profound mistakes, with many decades of unfortunate consequences, if we can learn from the past. That’s what I meant when I began this piece with that phrase about ‘a sense of perspective’. In the short-term world of politics, where, we are told a week is a long time, history and the appreciation of historical events, can provide guidance for decision-making, but only if the politicians concerned want to learn. I well remember the despair of many colleagues working on archaeological projects in the Middle East, when Bush and Blair confidently announced their disastrous campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan. We will have to come to terms with the ill-will of the Arab world over the next century, let alone weeks. As mistakes went, that was a big one. But archaeology and prehistory deal with processes rather than events. So the perspectives we bring are longer-term. Maybe the children at primary school who are about to be taught prehistory will be less self-centred and arrogant. And with luck those that eventually become our leaders will have a better sense of their own limitations. With luck…

November 20, 2013

Tidy and Oh So DULL!

I hate, loathe and detest unnecessary tidiness. Fine, be tidy in your workplace, or in the kitchen, where you need to know where certain key things are kept, but why is it that we English have to extend our tidiness to most other aspects of our lives? I can remember as a child being driven to London and looking at the suburban gardens as we passed them by. In early summer the daffodils that had been flowering a few weeks earlier, now had their leaves looped-up in neat little knots. At the time, I was just starting to get interested in gardening and I remember asking my father why people knotted-up their daffodil leaves. ‘They think it’s tidier’, came the reply. Then as an afterthought: ‘And of course you can cut closer to them with a mower.’ And of course he was right. I took another look: and each knotted-up daff protruded through an aggressively short lawn, whereas in our garden the daffs were planted in natural drifts where the grass was allowed to grow long and wasn’t cut back until later July, when the daff leaves had all died-back.

But this obsession with tidiness in our gardens can be terribly bad for wildlife. Hedges don’t need to be cut two or three times a year, not, that is, if you want to keep any nesting birds. I also don’t like to cut too many perennials’ seed heads off in the late summer or autumn, unless, that is, the seedlings can be very invasive (with us, Iris siberica is a real pest). We will tolerate a few Aster seedlings in the spring if it means that the sparrows and other finches have a good source of winter food. So our garden isn’t obsessively neat and tidy. I try to cut the lawn weekly during the peak of the growing season, but that’s a matter of self-preservation – miss a cut in June or July and the grass gets too long to cut without a scythe or a tractor. I also try to keep the lawn edges trimmed, if only because flower beds look much better if they’ve got a good, sharp edge; but even so, the edge-shears only come out three or at most four times a season. To be quite frank we’re not great ones for aggressively dead-heading anything, as we both like the look of seed heads, especially the nice fluffy ones you often get on clematis.

I like to leave seed heads in place until the spring. Here it’s an aster.

Meanwhile, back to the current year. As readers of this blog in Britain will know, it has been an extraordinarily warm autumn. We had our first ground frosts last week, no less. Normally by now – and we’re starting the run-up to Christmas – we’d have had several air frosts. Yesterday evening we ate the last courgettes! And in late November! I ask you.

We’re currently also enjoying the last of the autumn leaf colour and of course the flowering heads of tall grasses, such as pampas and molinia. The bright bark of the dogwoods is starting to be evident – an early sign of winter. And we’ve also been lighting fires for the past week. By way of contrast, last year we lit the first fire in mid-September. In the evening we’re regularly visited by a pair of buzzards who like to terrorise the pigeons and crows in the wood, where I’ve also been hearing the barks of Muntjac deer – so we have to keep the gates into the vegetable garden locked, as I’ve no intention of losing all our winter sprouts and cabbages to them, as happened two years ago.

Pampas grass growing in a shrubbery – this time it’s Pampas Gold Band.

The pair of giant (and very unfashionable at present) Sunningdale Silver pampas grasses out in the meadow. I cut them back quite hard in February with a powerful hedge-trimmer.

Very late autumn colour. A Miscanthus grass behind Verbena bonariensis, unusually still in flower, thanks to the warm autumn.

And on the subject of vegetables, I’ve moved the four sacks of potatoes that I had stored in the cool of the barn into the back door porch, together with net sacks of onions and shallots. There’s also a concealed heavy-duty tractor battery hidden in the picture if you can spot it (batteries, old tractors and night-time frosts don’t mix). The canvas bag is a free advertisement for our local animal food and garden supplier in Holbeach. And very good they are too!

The dry store in our back-door porch with paper sacks of potatoes, orange bags of onions and shallots in yellow and green bags, plus a few that need eating-up in a plastic saucer. Ignore the two plastic bottles of sheep wormer on their way out to the secure store in the barn…

So do I dread the coming of winter, as seems so common these days? No, I don’t. I like the long evenings and the crackle of logs in the grate. And it’s a good excuse to have a nice malt whisky while reading a good book. Lately I’ve been deep into M.R. Hall’s wonderful complex novels about the Severn Vale Coroner, Jennie Cooper. Like Ian Rankin and P.D. James he demonstrates effortlessly that genre books can also be literature. So far I’ve read two of the series The Coroner (no. 1) and The Disappeared (no. 2) and I’m currently half-way through The Redeemed (no. 3), which I’m reading in Kindle on my brand new Mini iPad. It has taken me about 6 weeks to learn how to drive it, but at last I’m slowly getting the hang of it (are my fingers unusually fat, or do other people have the same problems?). These days I only rarely swear at it, and threaten to hurl it onto the muck heap. But no, it’s the solution to our jammed-full book-case problems. And it’s also rather good fun. I even took a peek at Mylie Cyrus, as there has been so much fuss about her (and I quite fancied a cheap thrill). But I was horribly disappointed. Is it just me, or is she totally artificial and about as sexy as the big yellow plastic duck that takes up most of our bathroom?

October 19, 2013

Early Autumn – concupiscence and clichés

I suppose it’s inevitable, as more and more of the population moves indoors and experiences reality through digital media, that everything we take for granted now, will eventually become labelled and branded. So autumn is increasingly becoming the season of Colour. It’s an aspect of modern life I detest, but after repeated iteration who can be bothered even to growl under their breath when they hear the latest disaster served up to them as the ‘BBC News’. ‘No,’ I used to shout at the radio when the branding in question first happened, ‘The tsunami that has just hit Japan is news, pure and simple.’ The fact that it has been packaged and edited by the BBC does not give them control or copyright over the content, the news items themselves: that terrible tsunami was an act of nature and could never have been created by even the most powerful, over-paid executive at Broadcasting House. It was an act of God, if, that is, you believe in Him, or Her.

In fact, come to think of it, the branding of God and His subsequent commoditisation through the doctrine of Original Sin was the first great marketing triumph. The idea was based on the Bible, but was first proposed in a fully thought-out version by St Augustine of Hippo (354-430). It was soon taken up by the Pope, who, with his bishops and clergy, became the sales force who told their congregations that because of their Original Sin (which, of course, they could do nothing about), if they wanted to be given the chance of going to Heaven they would have to buy-in to their brand, the Church, lock, stock and barrel: they must follow its rules and, if necessary, they could start to buy their way into Heaven, through Indulgences and the funding of priests and chapels. It was a brilliant wheeze! And if the people didn’t co-operate, the future would be bleak, not to mention fiery. It was a lethally clever idea which tapped into people’s innate feelings of guilt. Everyone was guilty for the simple reason that Adam had rebelled against God in the Garden of Eden, because he was moved by his desire for Eve, which perfectly natural feeling was described by one of my favourite words in the English language: concupiscence. And haven’t we all felt a touch concupiscent at times? Now how on earth have I got to concupiscence, when I set out to describe my garden in the early autumn? Oh dear, I fear I have been seduced not so much by desire, as by digression. Yes, I have digressed, and woefully so. Mea culpa.

Now where was I? Ah, yes, I had started talking about autumn colour, or rather Autumn Colour, as we so often read it in the gardening press. Certainly autumn hues can be very striking, but there is far more to the season than colour alone, and besides, the truly vivid leaf tones don’t really start to happen until there have been at least a couple of sharp night frosts – and as I write, there haven’t yet been any. Personally, I savour other aspects of autumn too. I love the transformation when borders are cleared-out and when hedges are cut (although we always try to leave a few flowers to form seeds, to feed finches over the cold months of winter). So I took some pictures from upstairs, first showing how the garden is suddenly pulled together by the freshly trimmed hedges.

That first picture, which can be compared with that at the masthead of this blog (taken in November, as I recall), also shows in the foreground the small white flowers of the wonderfully scented sweet autumn clematis (C. maximowicziana ), a native of Japan, but now a major invasive pest in several States of the U.S. Our plant was severely cut-back by the frosts of the last two winters, but is recovering well now. I’m glad to say it doesn’t seem to produce seedlings in eastern England. The second picture shows quite well how the hornbeam hedges are now starting to give a feeling of ‘rooms’ towards the centre of the garden.

My last photo is also from upstairs and it shows some early autumn colour and textural contrasts: the scarlet berries of the firethorn, Pyracantha ‘Orange Glow’ (foreground), a fine variegated ivy (Hedera canariensis variegata) on the wall, a golden honeysuckle (Lonicera nitida) hedge and, behind them all, the reddening leaves and berries of the native Fenland Guelder Rose (Viburnum opulus, var. compactum).

October 12, 2013

CADS and Unbounders

Oh dear these clever titles are becoming addictive. For those younger than sixty, the title of this post is a clever/terrible (delete as applicable) pun on the Edwardian London Gentlemen’s Club-land saying: ‘I say, old chap you’re behaving like a cad and a bounder…’ It should be declared in a bored voice by a chinless wonder in a dinner jacket (Tuxedo in the US), holding a glass of port and looking down his aquiline nose at an ‘oik’ (or ‘pleb’ in Tory-speak) who has just pinched (in the sense of stolen, rather than having applied firm pressure to a fold of buttock, or skin) his girlfriend. My favourite dictionary, Webster’s New World, defines ‘cad’ as: ‘man or boy whose behaviour is not gentlemanly’ and ‘bounder’ as: ‘[Chiefly Brit. Colloq.] a man whose behaviour is ungentlemanly; cad.’ So they’re essentially synonyms. Somehow Webster always manages to de-pomposify, to coin a phrase, us Brits. But by now I’m beginning to regret having tried to be so clever.

In this case the CADS of the title refers to an excellent, if irregular, magazine about Crime And Detective Stories. CADS is written for rather obsessive readers of such stories by other readers (who seem even more obsessed) and by the authors of the stories themselves.1 One of the things I immediately took to was the warning at the head of certain articles that they gave away the plot of certain books. How often have I read reviews that did just that to books and films: ‘look out for the unexpected twist at the end’. Well it’s no longer unexpected, fat-head! You’ve just wrecked the book for most readers. CADS is peppered with reviews of new and older books and wonderful profiles of authors and obscure aspects of crime fiction. I bet you didn’t know that James Turner (1909-1975) wrote twelve novels featuring his detective Rampion Savage, with fabulous titles like The Stone Dormitory or The Frontiers of Death. Oh dear, suddenly The Lifers’ Club, my own venture into the genre, suddenly sounds very tame. Anyhow, the reason I’m writing this blog post is to tell a waiting world that I’ve done a piece for CADS: ‘My Journey into Crime: Explanations and Excavations’. It’s about what motivated me to start writing fiction and then how I came to get involved with Unbound, the unconventional crowdfunding publisher. Although I say so myself, it reads rather well and I make quite a good case for subscribing, because the list will remain open for a few more weeks. So there’s still time to see your name attached to a work of fiction that will soon became a classic. Just imagine, if every time you opened The Hound of the Baskervilles, there it would be, your name, for all the world to see and admire…

So if you’re seeking immortality, I would strongly suggest you IMMEDIATELY subscribe to The Lifers’ Club, because it’s certainly a lot cheaper than cryogenics. Take your credit card for a visit to:

http://unbound.co.uk/books/the-lifers-club

And then spend money like water. You know it makes sense – and Christmas is only just around the corner.

1 You can obtain a copy if you contact the Editor, Geoff Bradley at Geoffcads@aol.com

October 8, 2013

Mind the Gap!

I do apologise for the month-long gap since my last blog post – and also for the terrible title of this one, which will, I’m afraid, be a bit of a catch-up and hotchpotch. But so what, we do hotchpotches rather well in Britain – in fact we’re being governed by one at the moment: coalition, hotchpotch – what’s the difference? But I digress…

First, I must explain the main reason for the gap, has been the book I’ve been writing for Penguin over the past two to three years. I finished the first draft towards the end of August, then set it aside for a about three weeks, while I immersed myself in the start of the script-editing phase of Lifers’ Club. Essentially that was all about catching inconsistencies and cranking-up the drama at the start of the book; we might even have laid a few false trails, too (but that would be telling, so I’m saying nothing). Next week I’ll resume work on the script-editing, with the aim of completing it by the end of October. That way, we’ll still be on track to have the book printed for our lovely subscribers (who may now bask in the glory of having helped give birth to Alan Cadbury), in early May. That gave me most of September and early October to revise the first draft of the Penguin book, which I finished yesterday at 11.35 am. Sadly, Monday is our booze-free day, so I had to settle for tomato juice (in which we are currently swimming); I’ll crack open a bottle of Cava soon – or when my liver feels ready to receive it. The deadline for delivering the Penguin book is October 31st and I plan to re-read the manuscript one more time before then, to see if I can spot anything that seems grossly wrong, or out of place. Thereafter, I’ll be in the hands of my capable commissioning editor, Thomas Penn, incidentally, a very good author in his own right: his beautifully-written biography of Henry VII, the first of the Tudors, Winter King is a superb study of political cunning and ruthlessness – quite makes our current political leaders seem a bit weedy and wet. But I digress (again).

About a week ago my work on the Penguin book was rudely interrupted by a phone call from our neighbour Obie, who had just returned from taking his horse for its morning exercise along the small medieval droveway that runs outside our farm. He reported that during the night fly-tippers had set fire to a load of rubbish and builder’s rubble in one of our gateways. I went up there and pulled a piece of paper with a local address from out of the embers and then I called the fly-tipping people at the local District Council. They have agreed to clear-up the mess and they reckon they might be able to nail the culprit with that piece of paper and the fact that some of the rubble included fresh, and very unusual, paving material. Meanwhile, of course, I can’t use the gateway and the gate has been badly damaged by the flames. Who says there is such a thing as a victimless crime? Fly-tipping disfigures the countryside terribly, so I do hope these people get caught.

The delights of rural Britain: fly-tipping in one of our field gateways.

So when I was not talking to officials from the District Council, or staring at a screen, I was picking those plum tomatoes I described at length in the last blog post, if you can remember that far back. The crop is gargantuan and I’m giving all my friends and acquaintances bags of them, as I’d hate to throw any away. The main picture shows what are currently ripening on our sitting room floor, but there are more (maybe twice as many) out in the greenhouse, and another large batch are still on the vine, waiting to be picked next weekend, if the frosts hold off. I think next year I’ll do half as many plants. Last night I dreamt about making a rich red tomato wine…

Those Italian plum tomatoes ripening on our sitting-room floor.

Close-up of ripe tomatoes.

It has been a wonderful early autumn so far and tomatoes aside, we’ve both been very active in the garden. There’s been a huge and very tender crop of runner beans and our Borlotti and Cannellini beans, which we keep for drying, are superb – and that despite planting them quite late, because of the cold, wet, early summer. Every other day, too, Maisie picks a large bunch of sweet peas, which make the kitchen smell of summer. Gorgeous, especially first thing in the morning. I also like decorative fruits and berries, if that is, the grey squirrels allow them to survive. On the Poop Deck near the house we keep various exotic plants, including an unusual example of Dianella nigra (the New Zealand flax lily), which we bought from a friend locally and which I’ve pictured here for its wonderful dusty blue fruits, which catch the dew first thing in the morning. Now a word of warning: these plants can be tender and are best moved inside over winter, but don’t put them in the toddler’s bedroom, as they are probably deadly poisonous!

The berries of Dianella nigra on a dewy morning.

I must confess that most of my late summer and autumnal archaeology took place inside my head, but I did manage to find time to visit a wonderful excavation of a Victorian romantic hermitage hidden away in a wilderness alongside the stream at Belton House, near Grantham. The dig was being run by Rachael Hall, an old friend who is now a senior archaeologist with the National Trust. We visited the dig on Families Day and the site was alive (I nearly said crawling with) with young children and toddlers, none of whom fell into any of the trenches – although I’m not sure whether that was more down to their vigilant parents than the kids themselves. Not only did they find the lower walls of the hermitage, but the gravel path that led from an ornamental bridge over the stream, whose footings were being exposed on the bank. But there was a lovely friendly atmosphere when we visited – and this surely is what archaeology should be all about.

The garden excavation at Belton House, near Grantham.

September 9, 2013

Italian plum tomatoes – the best for cooking

I know I’ve said it before, still, it’ll bear repeating, that as I grow older I find I enjoy my food more and more. But it’s not about clever cheffy sauces and fancy restaurant-style cuisine. I leave that to you city dwellers, where real food is hard to come by. No, I like cooking (or more to the point, Maisie’s cooking), not cuisine, and I passionately care about good, fresh, healthy ingredients. If you’re working with supermarket broccoli you can dress it up with anything you care to mention, but it’ll still taste of green water. But having allowed myself that little tirade, I should add that there are exceptions to my ‘fresh’ rule, such as home-made jams, pickles and preserves. We also do a range of dried things, mostly beans (Cannellini and Borlotti) and occasionally fungi, but our three big freezers are the way we deal with those gluts that are a part of vegetable-gardening. So this year we’ve frozen bags of (blanched) green peas and broad beans and these are infinitely better than the peas from Mr. Birds Beak and other commercial freezers.

The other veg we freeze in bulk are tomatoes, which we simply place in bags when very ripe (slightly under-ripe and they thaw-out to an unappetising pinkish colour). We grow standard round red tomatoes, Gardener’s Delight, for salads and another maincrop variety (which changes from year to year) for early cookers. These are grown under glass and start cropping in late June/early July. Meanwhile out in the vegetable garden, I grow a row (12 plants) of San Marzano, Italian plum tomatoes. Last year it was so wet and cold that the entire crop succumbed to blight. But that’s the only year in the past four decades that that’s happened. And this year promises a bumper yield.

Plum tomatoes get their name from their shape, and they grow on bushes where you don’t pinch-out the side-shoots that appear at the base of the leaf stalks. This results in dense green bushes. In Italy the heat of the sun and the dryness of autumn naturally causes the leaves to shrink and the tomatoes to ripen, but in England that doesn’t happen: the leaves and young shoots stay green and lush, so the large fruits produced early in the year (and lying deep within the bush), don’t ripen, and worse, they rot – and the rot spreads. So I’ve taken to doing nature’s job for her. I remove all leaves and shoots along one side of the row, and lift the tomatoes off the ground, using canes and metal cloche-arches. It’s a long job (took 3 days this year), but it’s well worth it. On the other side of the row I remove most of the leaves and shoots and do my best to raise the lower fruit off the ground, using empty plastic flower pots. I also chuck away any rotten fruit, but I accept that this side will be far less productive than the other; having said that, the leaves that I’ve left do provide the plant with the energy it needs to enlarge smaller tomatoes.

Plum tomatoes are particularly good for cooking because they are not over-juicy and you don’t need to reduce (i.e. boil) sauces too much – a process that inevitably removes subtlety of flavour. If all goes well and the autumn remains fine, we’ll be handing jars of home-made ketchup to our friends at Christmas. And the flavour! Makes all the work seem worthwhile.

This year’s row of San Marzano plum tomatoes, before removal of surplus shoots and leaves.

The same row, after pruning.

Close-up of ripening plum tomatoes.

September 6, 2013

Viv Stanshall, a tyre blow-out (and a new picture of my mother)

Last Saturday would have been my mother’s one hundredth birthday, had she not died in 1980. To celebrate the occasion my elder sister organised a small family party down in Gloucestershire, where she lives. She asked us to bring any photo albums we might have, so that the younger generation of our mother’s grand- and great-grand-children might get an impression of what she looked like. So the evening before the event, Maisie was going through a couple of old albums that had lurked in the darkest recesses of a chest upstairs, when I heard a squeal. She had come across this picture I took when Viv visited the family home in Hertfordshire in, I think, 1973. Some might find his appearance unusual, even for the early seventies, but Viv’s eccentricity was never ill-considered, nor in anything but the very best of tastes. Only his idea of taste was not as other mortals: I sometimes think he could even warp the laws of physics, if he put his mind to it. And those socks are surely gravity-defying. And as for my poor mother: she never liked having her picture taken, despite the fact that as a young woman she had been exquisitely beautiful – but in a strong way. Her appearance was a statement not a blank page, like so many current, big-eyed, girly models. Or am I being hopelessly sexist? Probably, but what the Hell.

Anyhow, we loaded the album into the car and headed south-west, away from the Fens. We had barely left Peterborough behind us, when there was a sickening bang and the off-side rear wheel tyre blew-out. Maisie who was driving at the time, did well to steer us off the dual-carriageway and onto the verge. Changing the wheel was hairy, as only the lorries pulled over, cars preferred to give us frights. After about ten minutes a passing farmer drew up and parked his car further out, so that brain-dead drivers had no option but to budge-over. I’m so grateful to him: whoever you are, MANY thanks! Then I put the stupid, flimsy pretend-spare-wheel on and we limped back home, at a snail’s pace. What an anti-climax. But still, we found that picture and can share it now with everyone. Enjoy!

August 22, 2013

My Favourite Pictures (2): The Ribblehead Viaduct, North Yorkshire (1876)

On a clear sunny day the Ribblehead Viaduct can look as stunning as anything in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. I’d visited the place three times, first when doing a recce and then twice (start and finish) when we were filming that episode of Time Team where we excavated a navvy camp at Risehill, on the Settle-Carlisle Railway. It was the last major line to be built by navvy labour, between 1870-77. And as railway construction projects went, it was one of the most challenging, with bogs, hills and deep valleys to be crossed on many occasions. In fact it was so expensive to build and maintain that it has never really proved profitable.

We filmed on Risehill in 2007 and it was always raining, just like in the 1870s. In fact that was the only Time Team I can recall where we actually knocked-off early on Day 3, because of the rain. It didn’t feel like ordinary rain, because we were actually inside clouds; I can remember thinking that if I looked up, I’d probably drown. So all the pictures I took in October 2007 were grim, cloudy and threatening. But that didn’t worry me at the time, because the story I wanted to tell in The Making of the British Landscape was also rather grim: how 200 navvies and members of their families died in the navvy camps out on Blea Moor Common, and elsewhere. It’s a horrible story of privation, lack of hygiene and rampant disease. Most of the people were buried in unmarked graves in the church at Chapel-le-Dale, nearby; only the railway company wouldn’t pay for stone grave markers, so they used wood, which rapidly rotted-away in the wet climate. That still makes me furious – and was one of the reasons I decided to go with the gloomy, misty pictures.

Then my publishers decided that we couldn’t have full colour throughout, or the book would be prohibitively expensive (and in fairness to them, the manuscript we eventually agreed on was 125,000 words longer than they had originally requested!). So we had to go through all the plates that were to be reproduced in monochrome. Many were fine, but the picture of Ribblehead simply didn’t work at all. It was a symphony of soft greys, with a hint of bridge arches lurking somewhere in the middle. Having said that, the colour image works very well, I think.

The Ribblehead Viaduct on a rainy day. Note the humps and bumps left by the Blea Moor Common navvy camp, in the foreground. This is now one of a handful of legally protected (Scheduled) navvy camps in England.

Then a few weeks later, in early April, 2009, I discovered that I was to do a Radio 4 programme in the North Yorkshire Dales (I think it was an episode of Open Country, about the Settle-Carlisle railway). So I took my camera along with me, on the off-chance. Anyhow, one day God decided to take pity on me and the morning of April 5th dawned clear and cloudless and it was then that I got the sunny view of the Viaduct which appears in black-and-white on page 522 of The Making. But now you can see it, for the very first time, in full colour. And though I say so myself, it’s a pretty nice picture. Having said that (and I know I should probably keep quiet), but I still rather prefer that cloudy, moody picture. It suits the haunted soul of the place so well…

The Ribblehead Viaduct on a sunny day, also from the Blea Moor Common navvy camp. The collapsed stonework in the foreground seems to have been part of a camp building.

Francis Pryor's Blog

- Francis Pryor's profile

- 141 followers