Francis Pryor's Blog, page 16

July 29, 2014

Sorry About the Silence

It has been a long time since I sat down at this keyboard and up-dated my blog, but I’m afraid events got the better of me. After all these years, I’ve discovered that I am indeed human and bits of me can sometimes cease to function. In that respect I’m rather like my old (1964) International B414 tractor which didn’t operate in the early summer because a family of wrens had decided to take up residence, and raise a small family, inside the lift-arms of the muck-bucket. They didn’t move out until well into June, by which time the grass in the orchard was up to my waist.

Lambing went well and finished in mid-April; and for a month thereafter we concentrated on feeding the lactating ewes and looking after the lambs. Quite early in May I had a consultation with the dermatology specialist in Kings Lynn Hospital, who suggested I should start the course of skin treatment I discussed in my last blog post. I applied the first cream on May 14th and by the end of the month it was starting to feel very uncomfortable. At this point I will show a selfie of my face that I took yesterday:

I think you’ll agree I’m looking very much better. The pain has gone entirely as has the dryness and flakiness. I don’t need to apply aloe vera and moisturiser, but I do – just to be safe. And you’ll never find me outside without my trusty Canadian Tilley Hat and a layer of factor 50+ sun-block. I finished the course of cream on June 28th and I have to concede, it made me feel pretty grim. It took another three weeks to feel better, but after a fortnight progress was quite rapid – helped by rose-hip oil pressed on me by kind neighbours and my new friend-for-life, pure, unscented aloe vera gel.

On July 1st we sheared our much-reduced flock of about 50 sheep and were delighted to welcome a new shearer, Kaylee Campbell (all the way from sunny Norfolk) who did a fabulous job and treated the animals with enormous care and consideration. It was a treat to watch Kaylee, who must weigh around half my weight, handle 60 kilo ewes as if they were made from Styrofoam. Admittedly she did need some assistance when it came to the largest rams (90 kilos?), but then so did most of our previous shearers. When it comes to rams, shearing doesn’t always follow the textbook. It must be fun to watch.

Meanwhile, throughout June I was carefully reading and correcting the first and second proofs of my Penguin book, HOME: A Time Traveller’s Tales from British Prehistory, which will be published on October 3rd. I also managed to pull a muscle in my back, probably because I was so unfit thanks to the face cream and enforced periods of inactivity indoors – frankly it hurt to rub-in sun-block, so I couldn’t venture outside. So I read many of the proofs at an improvised ‘desk’ of piled-up cardboard boxes. That way, I could at least stand and read – which was much more comfortable.

Between batches of proofs, we managed to snatch a 5-day break at the Vivat Trust’s wonderful little Church Brow Cottage at Kirby Lonsdale, Lancashire. I feature it in The Making of the British Landscape (pp. 502-3). Vivat have done a wonderful job there: the garden is kempt, but rambling and the place has a splendid authentic Regency feel to it. And even the supermarket in Kirby is superb – why don’t we have a branch of the wonderful Booths in south Lincolnshire?

I returned to more proofs and captions, then on July 15th our neighbour, Charles, cut the hay. It was blazing hot weather and the forecast outlook was good. On July 17th he turned it, then rowed it up ready for baling on July 18th. I took this picture as Charles was setting-up the tedder:

The baler was meant to arrive around noon on the 18th, but couldn’t, because at 11.00 AM a solitary cloud meandered in from off the North Sea, presumably bored and desperate for a leak, spotted our hay and relieved itself. Then it thundered and rained over the weekend. It dried out on Sunday afternoon; the dry spell continued and Charles was able to bale on the following Tuesday. Then more picture proofs arrived. At the end of that week I went up to London, feeling a bit stiff after driving my International for 8 hours the previous day, shifting bales, and signed copies of the Lifers’ Club at Unbound’s office tower (two rooms, actually) in Dean Street, Soho. While I was there I Tweeted this picture:

And Twitter now tells me that people (or their pet cats, in the case of my friend Mark Allen) are receiving their copies. I hope they arrive in time to be read in bars or on beaches during the summer holidays – I also hope the book keeps folk awake, just a bit…

And to add to the mix, I’ve been writing Alan Cadbury’s second murder/mystery, also set in the Fens, but this time in the peatlands around Ely. It’s turning out to be a rather different sort of book and although I’ve planned it in some detail, it’s changing quite a lot, as I write. The characters have taken over and I’m doing my best to record what they’re doing. It’s strange to be playing catch-up with your own creations.

Anyhow, I thought I’d close with a moody sunset view, taken from our bedroom window:

Sometimes a picture just works – one can get it spot-on. Although as I look at it, I don’t recognise my own hand in it. I can’t help wondering: was it me, or Alan Cadbury who pressed that shutter?

June 5, 2014

Sunburnt Skin Isn’t Sexy

My father was fair-haired, one of my sisters is blonde and we’re all descended from Vikings – or that is what Oxford Professor Bryan Sykes’ laboratory discovered when they analysed the mitochondrial DNA in my blood. So I blame Eric Bloodaxe the Skullsplitter, or a similar friendly Dane for my reddish blonde colouring. And red-blonde skin (sometimes called auburn) is what burns the worst, or so I’ve been told. Having said that, I’ve known from when I was a small child that I burn in the sun. True, ultimately I will tan, but that process requires me first to go bright red and then to peel . After that I do start to tan. And of course my hair rapidly goes white blonde after a few weeks of summer sunshine. And yes, I suppose I did look slightly more attractive to the opposite sex when I was fit, young, tanned and blonde, but even so I was never a Robert Redford, nor a Steve McQueen. In retrospect I shouldn’t have bothered, but then the minds of young men in their teens and twenties, on those rare occasions when they are not rendered completely useless by the over-secretion of testosterone, don’t have time to think such sensible thoughts. Or at least mine didn’t.

Then when I became a full-time field archaeologist I wore cut-down jean shorts, boots and not much else. And that was every year, from April/May to the end of October. Meanwhile, of course my skin was being attacked by the increasingly strong rays of the sun, which, I gather, are even more harmful now that the ozone layer has been depleted. I rarely wore a hat, as it made my very long hair go all sweaty. And sunscreen didn’t become available until the 1990s, but when it did it was so scented you ended up smelling like a whore’s boudoir.

I started to be conscious that I’d damaged my skin quite badly in the late 1990s, when people in general became more aware of sun-damage. But by then it was too late. I’ve already had a malignant melanoma removed from my left shoulder. Mercifully it was quite small (6mm across) and shallow (less than 1mm), but it had to be removed under anaesthetic and it gave me one hell of a scare. The next ordeal I’ve had to face (quite literally) is a 28-day course of a viciously strong ointment called Efudix 5% fluorouracil cream, which I apply to my face every morning, after my first daily session of writing Alan Cadbury’s second adventure for Unbound. Then I have to stop doing anything for a bit, while the cream digs into my skin and set about killing all the pre-cancerous and sun-damaged cells on my face. I won’t say it’s painful, just very, very unpleasant. And it makes my face look like something at Madame Tussaud’s waxwork horror gallery.

So I’m writing this to warn younger archaeologists, farmers and gardeners, especially those of you who are blessed with fair skin, to wear good, strong sunscreen (at least S.P.F. 30) on your faces. You’ll still tan, but more slowly. I’d also strongly recommend a wide brimmed hat, although I’m well aware that swinging a mattock is difficult in a hat. So put one on when you pause to gather breath. The thing is, when people think of sunburn, they imagine their backs and shoulders. But in actual fact it’s your face that’s most at risk.

And I really DO mean it. No matter what your age, but most especially if you’re young, PLEASE heed my warning. You must act now and with luck you won’t have to face the many unexpected horrors of long-term skin-damage, of which the worse, of course is the dreaded C word: cancer. So if you’re young and fair, PLEASE, PLEASE COVER-UP!!! The sun isn’t something to mess with. So out with the hat, and on with the sunscreen: I promise, you’ll never regret it. I’d hate to think that in a few decades’ time you’ll have to put powerful creams on your face that will make you look like this (isn’t it sad, this is only my second selfie; the first featured two china eggs – and is actually a lot more sexy!):

This is not sunburn, this is the treatment for a lifetime of sun exposure.

May 17, 2014

Truth, Archaeology and Fiction (2)

As time passes I find I am more and more interested in what we mean by the terms Truth and Fiction. Indeed, the more I think about it, the more convinced I have become that analysis won’t help me come to grips with the problem. In fact I’m becoming fairly (but only fairly) certain that our modern, western obsession with what I might call the ‘scientific’ approach has its own limitations, too. I think as a culture we place too much emphasis on analytical thought: on observation, hypothesis and test – the three classic steps of science. As an archaeologist I am, of course, thoroughly steeped in this tradition and it affects not just my professional work, but my attitude to life in general. When I was a student at Cambridge in the mid-1960s, archaeology was starting to shake-off an earlier tradition of historical- or narrative-based thought and replace it with something more overtly ‘scientific’. My sympathies still generally lie with the reformers, because the new approaches did inspire hugely improved excavation techniques and an ability to think more originally and to come up with new interpretations which were less hindered by rigid conventions. But there was a cost to this progress.

Today students and academics in archaeology still have to accept what is essentially an analytical climate of thought, or ‘paradigm’ to give it its jargon name. As a consequence, the brightest students tend also to be the most analytical – no surprises there – but often they lack those other, more intuitive, skills which make for a good researcher. In my experience most team leaders and innovators have good degrees, but not brilliant ones. The brilliant people tend to become quite narrow specialists, which a cynic might suggest means they are not brilliant at all. Except that they are, and have starred first class degrees to prove it. The problem lies at the university, where analysis is God. I think you have something similar going on in the field of English Literature, where the great analysts and critics, one thinks here of people like F.R. Leavis, couldn’t write a good novel, even if they wanted to. Similarly, most musicologists are uninspired as composers. Of course there are notable exceptions (one thinks of the Dept of English at the University of East Anglia), but as a general rule, analysis remains at the heart of the western academic tradition. And of course there are good historical reasons for this, going back to the Enlightenment and even earlier, to the Renaissance, and the struggle of people like Galileo with the anti-analytical self-interest of an all-powerful Church. Given the choice between Pope and Professor, I’d opt for Prof. every time.

When I was a student I soon realised that I wasn’t clever in an analytical way. I still can’t do Sudoku or crosswords, but on the other hand I found statistics relatively easy to grasp (largely I think, thanks to a wonderful book by M.J. Moroney: Facts from Figures), but only when I had a good, well-defined reason to employ the knowledge, which happened to be the spatial distribution of objects found in our excavations. At university the emphasis seemed to be on analysis for its own sake, which struck me then, and now, as pointless. So I did other things. I was active on the then rapidly developing rock music scene; I rowed to keep fit; I drank lots of beer to counteract the training; and I read. And how I read: everything from Tolstoy to Henry Miller, via Dorothy Sayers, Conan Doyle, Tom and Virginia Woolf. The thing is, I knew in my heart-of-hearts that I wasn’t much good at analysis and that even if I worked twenty-five hours a day the best I’d manage might be a rather lack-lustre 2/1. So I decided to do a little bit more than the bare minimum and get a workmanlike 2/2 – which is what happened. And I’ve never regretted making that decision. What I didn’t appreciate back then was, that by avoiding the approved, but very limited, academic menu that was then on offer, I was giving myself a real education, as opposed to an over-specialised training.

So the books I began writing later in life, starting with Seahenge back in 2001, were only made possible by the fact that I hadn’t allowed the creative side of my brain to be strangled by academia. Indeed, Seahenge sort of wrote itself. It just poured out. In fact I spent more time editing and cutting it back, than actually putting words on paper. As time passed I learnt how to tame the creative beast and keep her more firmly under control (I’m convinced my muse is a female, because she doesn’t approve of me drinking when I’m at the keyboard). But everything I wrote was motivated by an urge to reveal to myself and my readers what it might have felt like to have been alive in a particular time in the past.

Now I freely concede, my impression of those feelings is based on my past analyses of data from excavations, but it isn’t as simple as that: at the end of the fieldwork stage in a dig, you do more than merely manipulate data. Writing a good and original final report is a creative process, as I think the very best examples illustrate (and I’m thinking here of people like Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Grahame Clark, Brian Hope-Taylor, Geoff Wainwright, Mike Parker Pearson and Richard Bradley). These reports represent some of the best combinations of analysis and creative imagination you’ll find in any humanity – but it’s only the analysis and techniques of excavation that ever get credited and I think it’s time we redressed that imbalance; what about the imagination that went into the conception and planning of the project, the composition of the specialists and the creative side of the report-writing? Why don’t universities treat this side of archaeology with greater respect, as I consider it every bit as important as mere analysis? In this debate I tend to be more concerned with the emotion than the analytical truth, which doesn’t make me a fantasist, either. Indeed, fiction can be truthful, as any reader of Tristram Shandy will know.

Which brings me back to the fiction/non-fiction/truth business. To be honest I see The Lifers’ Club as a natural successor to my latest non-fiction book, Home and its predecessor, The Making of the British Landscape. In all three books, I had to inhabit worlds and landscapes that were unfamiliar to me. If anything, Lifers’ Club needed less imagination, because it was all around me, all the time. It was almost like writing a diary, or, come to that, a blog. Now I concede that the style of writing is rather different from my other books, and very different from my academic reports, but the imagination and the mind-set behind them all was essentially the same. And I refuse to admit that the short-sentence, rather snappy style of the thriller is somehow easier to do than the more verbose style of the heavy-duty academic report (like my English Heritage volumes on Etton and Flag Fen). Far from it, in fact: academic writing can be very easy to do, simply because one can relapse into meaningless jargon, when the truth is proving difficult to nail-down. But flannel and bullshit stands out a mile in a tightly-edited crime novel, which requires more personal involvement, less posing – and none of the dreaded gravitas (a synonym for bloated pomposity). It also involves a huge amount of mental discipline and total immersion. Indeed, there were times when I was writing Lifers that I became quite convinced I was reporting things that had actually happened. Real life and fiction became confused. Characters in the book got mentioned casually over the breakfast table, as if they were there, beside us, spooning out the marmalade. Sometimes these little incidents could be quite upsetting, creepy even…

Anyhow, I’ve just learned that the ebook version is now published. Trouble is, I’m not sure I’ve got the courage to read it. Maybe later. Some day. And if you Tweet (@pryorfrancis), do let me know what you think of it.

May 13, 2014

Car, Bank, Mirror

Maybe I’m working too hard on my second Alan Cadbury book, or maybe I’m just going a bit weird in my old age, but today I fully intended to write the second part of my last blog post. Either that, or an instructive, yet quietly informative, item on spring flowering shrubs. But no I’m offering my patient readers this strangely pointless non-story – and there aren’t even any pictures…

We’re in something of a tailspin in the Pryor household right now: Maisie has very soon to return to her excavation and make careful observations on prehistoric woodworking, whereas I still have a small farm to run and am about to get involved with the launch of The Lifers’ Club and the proof-reading of Home, my latest book for Penguin. So we both tend to make lots of Do Lists, which we promptly mislay – but the value of those lists lies in their writing more than their reading (or so I tell myself). Anyhow, early this morning, while making my first cup of tea, I caught sight of Maisie’s Do List for our planned trip this afternoon to Spalding. There were three items:

Car

Bank

Mirror

I won’t bore you with the details of each, but the car was about a new license, the bank was about depositing a cheque and the mirror was a new shaving mirror I need, as I have soon got to apply some powerful cream to the sun-damage on my face – and being a beardie, I don’t possess one. Then, as I wandered my way from the kitchen back to my office to resume the chapter-by-chapter outline of AC2 (the second Alan Cadbury book), I found my mind was reciting Car, Bank, Mirror over and over again, shortly to be followed by Paper, Rock, Scissors. Suddenly I realised I had stumbled upon a new word game that families could use on those up-coming, interminable car journeys to the seaside. We all know the rules: paper beats stone because it can wrap it, stone beats scissors etc., etc. So this is how you play Car, Bank, Mirror. It’s so easy:

Car beats mirror (there’d be very few mirrors if cars didn’t exist)

Bank beats car (you can’t buy a car without help from the bank)

Mirror beats bank (bankers see no reflection when they look into a mirror)

Good eh?

May 3, 2014

Truth, Archaeology and Fiction (1)

From time to time over the years I have found myself working on two books – and it’s never much fun, so I have tried to avoid it. The trouble is that the human brain, or at least my own version of it, lacks the flexibility to switch between widely differing topics. So I would try to arrange the work into separate batches: say a week on The Making of the British Landscape edit, followed by a fortnight writing The Birth of Modern Britain. That way I could usually arrange for a weekend away from either book, to allow my mind to re-focus. Then, just over two years ago, and while we were planning and then filming the final (20th) series of Time Team, I had the idea of writing a book of fiction. By then I had signed the contract for my latest Penguin non-fiction book, Home, which is essentially a personal exploration of British prehistory, based around ancient and modern British home life. This has not been an easy theme to work on and I have had to rewrite it at least twice. You might suppose that a reminiscence is fairly straightforward, except that my perceptions, even in my 70th year (when my life and thoughts should have settled down) kept changing. And the task wasn’t made any easier by the subject matter, because I had decided to take the story of home life right back to the end of the last Ice Age, over ten thousand years ago and that meant straying into the Mesolithic – a period dominated by the obsessive study of flints and by ever more minute changes in the climate and environment. It’s a period that archaeologists of later prehistory, such as myself, who are interested in the lives of people, have tended to avoid. Nerdish categorisation scares me witless.

Then I discovered that things are changing in the world of Mesolithic archaeology. True, most specialists in the period seem to know little about later periods, but there are some notable exceptions and word is beginning to spread that there is more to the past than those tiny pieces of flint. This process has been speeded-up by the recent discovery of early post-Glacial houses dating back to the 8th and 9th millennia BC – which are about the same size and general shape as buildings of later prehistory. This has meant that we are having massively to revise our ideas about hunter-gatherer societies and their supposedly shifting semi-nomadic lifestyle. So my reminiscence has also been an exploration, which, to make matters even more complex, I have extended into my own life, and home-building, in the 20th and 21st century, AD.

I knew that the first version of what was later to be called Home wasn’t working. It lacked a central argument and theme. So I put it to one side and immersed myself in the Mesolithic period. At the end of that, I realised that the theme I was seeking lay all around me. It was the story of my own life and the way I was living; it was about why everyday family life is so important. I also began to question modern perceptions of home – as somewhere people can be packed away in order to keep them quiet. In reality home and family life can be a radical and creative experience. It was, after all, where the great ideas that shaped all societies were formed and developed. It’s the basic relationship, the fundamental building block of every human community. It was then, too, that I realised how hopelessly unbalanced modern British society has become, with a distant ruling elite in London – far from the world the rest of us inhabit. It put me rather in mind of the degeneracy of the patrician classes in ancient Rome, as described by the great Edward Gibbon in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

While these seditious thoughts were rampaging through my newly radicalised septuagenarian imagination, Westminster politics revealed itself in its true colours, as politicians of all Parties made concerted and blatant attempts to scare the Scots from voting for independence. I’m not Scottish myself, and I wouldn’t presume to influence my many friends north of the border, but after that disgraceful display of concerted moral blackmail, I know where I’d put my saltire on the ballot paper. So if Scotland does go independent, maybe we timid English will find encouragement to demand a bit of regional autonomy for ourselves? Let’s face it: apart from a theocracy, almost anything would be better than the current system.

April 21, 2014

Reasons to be Cheerful

I think it was a couple of years ago and we were both feeling fed-up. Lousy weather. Weeds everywhere in the garden. Nobody replying to emails. Savings shrinking. Car starting to make expensive-sounding noises. None were things that would be causes of real emotional pain, but their cumulative effect was very depressing. It was then that we hit on the idea of Reasons to be Cheerful. We had just been given, for Christmas, I think, one of those glazed ceramic write-on pads designed to be used with felt-tip pens. So far it had barely been used, then one of us – and I honestly can’t remember if it was me or Maisie – had the idea. It came more or less fully formed.

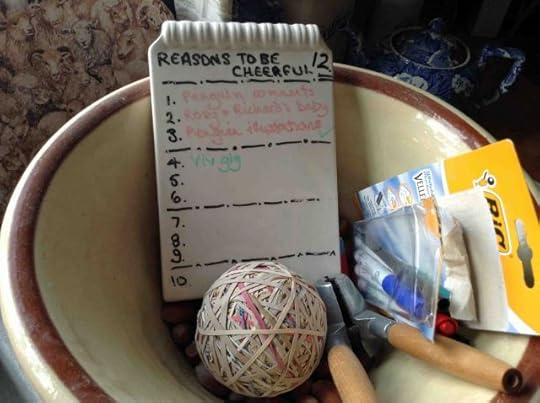

When you’re feeling down, all you seem able to think about are other reasons to be gloomy, and what you need to be able to do is break that vicious circle of doom feeding gloom and despondency. So we decided we’d flag up those small reasons to be cheerful that so often get overlooked when life in general is a bit grim. Maisie produced the write-on pad and drew-up the outline of our Reasons to be Cheerful score-card. I can’t remember how the first one went, but from the recent past we found three reasons to be cheerful that we’d just forgotten about in the then climate of persistent pessimism. I don’t know what they were, but they were good enough. We decided that three Reasons to be Cheerful earned us a bottle of fizz (usually Cava or Prosecco). It didn’t have to be drunk then and there, but that first one certainly was. Really (and I mean very exceptionally) important Reasons, such as the impending publication of The Lifers’ Club, earn a bottle on their own. Then came the touch of genius (which I have to allow was Maisie’s): after three bottles of Cava (i.e. at the completion of each page of the notepad) you earn a bonus bottle! Free!!

The photo shows our current score-card. We’re now on page 12 and have just drunk a bottle in celebration of our niece’s pregnancy, plus the acceptance (on two separate occasions) of various things for my upcoming Penguin book (current title: Home: A Time Traveller’s Tales from Britain’s Prehistory), which will appear in early October, if all goes according to plan. The wonderful Viv Stanshall gig was the first reason of the next batch of three. And so it goes.

I know it sounds a bit petty and silly, but our Reasons to be Cheerful help us celebrate the little things in life that have gone well. They’re not Reasons to be Complacent, nor indeed Reasons to be Insanely Jolly. Just Cheerful. And that’s good enough for us… Cheers!

April 15, 2014

Lambing, 2014

Every year is different. Some years are marked by tough, resilient bags that imprison the lamb when it is born and can quickly suffocate it, unless the ewe or one of us clears the membrane from around its nose. Other years have featured lots of multiples, shortages of milk or copper deficiency – which in turn causes lambs to stagger. You can do something about some of these, but this season was the year of the BIG single. We keep detailed records of each ewe’s lambing record and usually they start out with a year or two of singles, then twins, then triplets and even, in some cases, quads. But it’s very unusual to slip back the other way: to have twins followed by a single. But not this year. And it would seem we’re by no means unique. Our feed rep tells me that the orders placed with the manufacturers of lambs’ ear tags are well down, and all his customers are moaning about difficult births because of huge single lambs.

We started in mid-March and got off to quite a slow start. Whenever that happens we check what the weather was like 21 weeks previously, when the rams were mating (tupping is the phrase we use) the ewes. In the past we have found that ewes and rams fail to get together and have fun if it’s pouring with rain. Can’t say I blame them. It would put me off my stroke. And lo and behold, it was very wet when we put the rams in. A week later it came dry and 21 weeks later the lambing rate picked up rapidly. Then again it was wet in November for a few days, and again things slowed down in late March. Finally it went dry and there was a little surge in the last week of lambing, including, appropriately enough, a big single (to a very small ewe) on the last day.

One of the reasons I like lambing, despite the sleepless nights and aching back, is the sheer sensoriness (for want of a better word) of it all: the smells, the warm steam off a new-born lamb on a cold morning, the sound of ewes chewing the cud and the sight of chickens picking their way through a crowd of sheep. And in the background the soothing tones of Classic FM providing background music for both sheep and their farmers. In an increasingly remote, hands-off, digital world we all need to get our hands dirty sometimes. I don’t plan to give up before I’m 80 – unless, of course, the government introduces some damn-fool regulation that makes farming for anything other than pure profit impossible (which Westminster and Brussels between them are perfectly capable of doing). Anyhow, this lambing I’ve tried to make the first two pictures a bit atmospheric: a very (20 seconds?) new –born lamb, being licked dry by its mother and a group of unlambed ewes contentedly chewing the cud in the barn on a sunny morning in early springtime.

My final three pictures (at the end of this post) are of that wonderful day when we release the first batch of ewes and lambs onto the new, lush spring pasture. In the past I would open the doors and feed them their concentrated feed out in the field, but a few years ago a lamb had its leg broken in the rush, so I now feed them in the small barn and then let them find their own, hesitant way out onto the grass. It’s much slower, and gentler, as the photos show: first a couple of lambs at the door, trying to work out what the new world out there is all about. Then a ewe barges past them. Finally everyone has to head out. It’s my favourite moment.

We lambed about three weeks later than in previous years, largely because we had to wait for doses of the Schmallenberg Disease vaccine which had to be administered a month before tupping. That may have been the excuse, but in actual fact it worked very much better, all round: we were able to turn the ewes and young lambs out onto wonderful rich grazing and all are doing well in the fabulous mid-spring sunshine. It has been so much less stressful than earlier in the year. All in all, a huge success. I even managed to plant out my potatoes during one of the quieter spells. And now I must stop this and return to the vegetable garden to sow a quick catch-crop of early green peas (Douce de Provence this year). Roll on May!

March 26, 2014

Why Archaeologists Make Good Detectives

As most of my readers will know by now, I’ve written a crime/thriller (The Lifers’ Club) with an archaeologist (Alan Cadbury) as the detective. Then as soon as lambing is finished, I’ll resume work on the second book in the series, which for the time being I’m simply calling AC2. I’d always known that the way archaeologists work and think would make them good sleuths, but just two days ago a real life mystery was solved, not as it happens by Alan Cadbury, but by my wife, Maisie Taylor. This time the subject wasn’t crime, but a wonderful garden ornament, which for years we simply called the jardinière – as that is what it resembled. For those of you unfamiliar with the word, my Shorter Oxford Dictionary traces its origins to French (1841) and defines it as: ‘An ornamental stand or receptacle for plants, flowers, etc.’ Or to put it in even plainer English: a tub.

Our jardinière is made-up of eight tapering panels of unusually red, unglazed earthenware, which I have assembled as best I can (which isn’t very well). Sadly my reconstruction doesn’t bear very close inspection, largely because some of the panels are broken and it wasn’t very easy to repair them invisibly, although Maisie did a very good job forty years ago, using a mix of Araldite and brick dust; the point is, the mends must all be strong enough to resist frost and allow the object to be used in the garden again. There are four ornamental and four plain panels, which I imagine were meant to be distributed alternately, but sadly I couldn’t get that to work, so I’ve re-assembled it with most of the decorated panels facing forwards, towards the lawn. I’m well aware it’s not perfect, but our garden isn’t a museum. Anyhow, here’s a picture of the jardinière as it now is, planted with a few bulbs surrounding a young Cornus alternifolia argentea shrub. It forms the focus of a small border and though I say so myself, it looks very good there, especially in summer (when this photo wasn’t taken).

The story of how Maisie came to be the proud owner of the jardinière is interesting of itself and here are her notes to me describing how it happened (the title, I’m afraid is mine, with apologies to Swift; my comments are in square brackets):

The Tale of a Tub

1977 – travelled [by train] to the Institute of Archaeology several times a week [Maisie was a student there, commuting to London from Huntingdon]. Became on nodding terms with a number of people as the same group tended to share a compartment, because all needed to work on the journey.

One winter evening the train stopped in the middle of nowhere, and the lights went out [sudden power cuts were a regular feature of the time, brought about by strikes]. Began chatting. Turned out the other people were two barristers, a man who did something analytical with computers, a man who wrote history books, a brain surgeon and me. One thing we all had in common was we were all doing-up old houses. The others had Georgian/Regency farmhouses; I had a little Edwardian cottage next to the railway.

After an hour or so the lights come on and train continued – back to normal.

The following year, the man who knew about computers said he had dug something up in his garden, and as he knew I was an archaeologist, and lived in a turn of the century cottage, I might be interested. So he invited me to have a look.

It turned out to be an Arts and Crafts jardinière in fragments. The same date as my cottage. He liked it, but thought it out of place in the ‘Georgian’ garden he was creating around his beautiful Georgian house. So he offered it to me, and I accepted.

I planted it, although someone once suggested it might be a decorative well-head.

Meanwhile, Back to the Plot…

To be honest, we thought no more about it; then a few years ago I decided to attempt a slightly better re-assembly, as the whole thing was starting to fall apart, largely thanks to the efforts of rats and mice who were seeking somewhere dry for the winter. The rebuild took me a whole weekend, and we had plenty of time to examine the original workmanship more closely – and it became clear to us, that it was a piece of exceptional quality. It also had several clear stamps which looked Arts and Crafts – the lettering was a give-away; we could make out certain words, something like: ‘wheel within … a wheel’; Maisie even made rubbings of them, but then something else cropped up and we both found ourselves doing other things, and precious little time to relax with a large Victorian flower pot.

The stamp of the Compton Pottery, Guildford. The motto reads: “THEIR WORK WAS AS IT WERE A WHEEL IN THE MIDDLE OF A WHEEL”

Then a couple of weeks ago Maisie came across the distinctive wheel-like stamp when reading a reference to the Compton Arts Guild, near Guildford, which was set up in 1899 by various artists, including the distinguished painter G.F. Watts and his wife Mary. It was Mary who founded and then became the leading light of the Compton Pottery, which remarkably survived until 1954. They used the local clay which fired to the distinctive bright pinkish-red of our jardinière. The company produced a huge variety of garden ornaments, which you can see on-line (Google ‘Compton Pottery images’) and at the Watts Gallery, Down Lane, Compton, Guildford, Surrey GU3 1DQ.

Well-heads feature among their range of items, and as I’ve already mentioned, it has been suggested several times that our jardinière is one of them. Personally, I doubt it. Well-heads, even ornamental and model ones, always have thick, vertical walls because they were built to support the well winding-gear, which could be quite heavy, especially when lifting a bucketful of water. So the walls of the well-head were always vertical and never splayed, like the relatively thin sides of our jardinière.

Anyhow, it’s a very beautiful thing and it would be nice if one could see more real crafts and hand-made material at British garden centres, which tend to be packed-full of injection-moulded coy nymphs in concrete – and as for those horrible plastic gnomes…

March 19, 2014

The Iniquity of Unpaid Labour

When I began my life in archaeology in the early 1960s, I worked for several groups of amateurs as a volunteer. I had zero experience, even less knowledge, but boundless and ill-directed enthusiasm. Looking back on those times I am not surprised that the people in charge gave me heavy jobs, like shovelling, mattocking and pushing loaded wheel-barrows. That was usually in the morning. By the afternoon my surplus energy had been burned off and I was in a fit state to be taught the delicate and subtle arts of trowelling. At that stage in my life I had yet to start higher education, and I viewed the digs that I went on as part of that process. Put another way, I don’t think I was being exploited in any way at all; it was a genuine two-way process: the excavation made use of my youthful strength and I learned specialised skills and discipline, in return. It was also a relatively brief process that lasted for my pre-university ‘gap’ year. After just one year at university I was able to get paid ‘volunteer’ jobs followed, quite quickly, by assistant and supervisor roles.

I began directing excavations in 1971. Our digs were professional so-called ‘rescue’ excavations, which took place ahead of factory development on land that was soon to become part of Peterborough New Town. The people who did the hard work of excavations were still termed volunteers, but by now they were paid – although very little. I used to work as a paid volunteer on various mainly Ministry of Works sites when I was a student and I managed to pay off most of my debts and college bar bills that way. As professional rescue (now known as contract) archaeology became increasingly important in the later 20th and early 21st Century, amateur archaeology carved-out its own niche. Sometimes these were cheerful community-run, self-funded affairs, but they could also be highly rigorous research projects whose standards were at least as high as the very best in the contract world. The point I am trying to make is that in archaeology, the worlds of professional and amateur have acquired quite distinct and separate identities. Normally I am in favour of breaking down such artificial barriers, but for reasons that will shortly become clear, I am no longer quite so sure.

Over the past ten or so years I have been observing how members of the next generation set about finding work. Mine is a middle class family. Some of my relatives are well-off, others are less so, but most of their children have had problems gaining employment if, that is, they decided not to get a job in the worlds of farming, finance, commerce, law and industry. I won’t say that the youngsters who decided to follow those careers paths have been without their problems, but I don’t think they were exploited in quite the same way. And of course they were soon reasonably well paid. The people who have had a hard time were those who decided to work in the theatre and film/television, in social work, in charities, amenity gardening (as opposed to commercial horticulture) and the arts. And yet the sad thing is, these were all subjects in which Britain traditionally played a leading, pioneering role. They are also fields that have become professional and employ large numbers of people. But sadly a significant proportion of that supposed employment is nothing of the sort. Now I fully concede that from an economist or politician’s viewpoint you cannot have arts unless you also have people who are prepared to buy the created work; but today I think the scales have tipped too far in one direction. I also suspect that future critics might well judge that some of the films, plays and artworks produced themselves reflect that bias: to my eyes they are often either dumbed-down and over-populist, or elite and very metropolitan. What has happened to subtlety and charm?

Whenever I speak to people at the start of their working lives, one of the commonest complaints I hear is about their exploitation in the dreaded internships. Now I cannot speak from personal experience, but I have to say, these sound like little more than schemes to acquire not cheap, but free labour. Maybe I’m wrong: maybe there are good, non-exploitative internships, but it’s hard to avoid the other conclusion. What I abhor is the way that it has somehow become quite OK to exploit amateurs within a professional organisation. To my mind that idea stinks. It is moreover profoundly corrupting and is doing more to widen the have/have not divide and the distance between the Westminster political elite and the rest of the country than almost anything else.

I had long suspected that the situation was bad, but my eyes were only opened to the extent of the problem by a superb blog post by Alice Smith who has experienced internship many, many times. She writes from the bitterest experience and her words are given added strength by the fact that she has recently emerged on the other side and now has a paid job in the professional theatre world. And please don’t make the mistake of thinking that Alice is a star-struck wannabe actor. No, her interest lies behind-the-scenes, on the administrative and managerial side. She loves theatres and how they work. That’s what motivates her. It’s an absolutely gripping read, and not too long, either. And you must be made of stone if it doesn’t affect you. Take it from me: you MUST have a look:

http://alicelsmith.wordpress.com/2014/02/20/fringe-theatre-playground-of-the-privileged/

And if like me you Tweet, please tell others about it. And now I must get back to the lambing pens. Why can’t humans be as straightforward as other animals?

March 7, 2014

Norfolk Biffins (or Beefings)

I must confess I find the sort of apples one buys in supermarkets rather boring. Yes, they look nice and they are generally sweet and crunchy, but isn’t life about more than sweetness and crunch? What about flavour and texture? What about contrast and subtlety? There are times I worry about the dumbing-down of British palates, eroded by the incessant onslaught of marketeers’ blandness. Yes, I agree 100%: by all means ban the smoking of cigarettes in cars with children; but I’d also make it a hanging offence to eat fast-food in front of impressionable youngsters. And people who give their babies chocolate deserve to be slowly… But I digress.

Now where was I? Ah yes, I was going to write about Biffins. ‘Oh no,’ I hear a groan, ‘Not Biffins: everyone knows about Biffins.’ Well for that tiny minority who don’t, a few words of explanation might be appropriate. To sum up. If you went into any bakery in Norfolk in the 19th (I nearly said ‘last’) Century you would probably encounter trays of Biffins. And soon they had become very popular in London and elsewhere. Essentially, Biffins or Beefings were oven-dried apples, but of a particular variety (the Norfolk Beefing), which can still be found in select nurseries today.

According to Wikepedia, the oldest recorded reference to Norfolk Biffins is 1807. We planted our tree about five years ago and this autumn it gave us two apples. In Victorian times, bakers would put their beefing apples into their bread ovens as they were cooling down after the main baking session, to make use of any residual heat. We used the warming oven of the Aga (which runs at just below boiling temperature). The bakers would weigh their apples down with trays and suchlike, so give them their distinctive flattened shape, but this takes a certain amount of practice to get right; and of course too much weight would split the skins – and the biffin then rapidly dries out completely – to a leather-like consistency. So I pressed our two apples at the end of the process, when we reckoned the skins would be good and tough.

We grow about 15 types of old apples in our small orchard and we know from experience that many traditional ‘keeping’ varieties (such as the 18th Century (1708) Ribston Pippin, which we’re currently eating), develop sweetness and complexity through time. The textbooks suggest the best months to eat various varieties, but in our experience this will vary hugely from one year to another. Frankly, nothing can beat a few exploratory nibbles. Too often we’ve left the starting of a box of apples until the ‘correct’ time, only to find them over-ripe and woolly in texture.

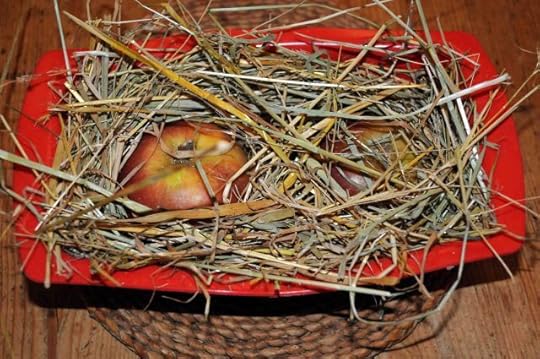

So first give the apples time to develop some taste and texture (we conducted our little experiment in early December). Then pack them tightly in fresh, dry hay (which you can buy bagged in pet and animal feed shops) in a dish or bowl. When you think they’re ready, press them carefully, while they’re still warm and flexible. Ideally they should be less than an inch thick, although I think ours turned out very slightly fatter. Or you can just place the bowl in the oven and check at hourly intervals. Failing that, you can do what we did: put them in the warming oven over-night, and hope for the best in the morning.

You can find recipes for cooking Biffins on the internet, but if you’ve gone to the trouble of making your own, I’d strongly suggest you eat them plain, without ice cream or custard. Frankly, they’re absolutely delicious. Incredibly complex with a wonderful lingering, aromatic aftertaste. Personally, I don’t mind eating tough skins, but some delicate modern mouths might find them a bit much. And I’d also leave the core (mindful of the fact that ripe apple pips are quite toxic if chewed). Oh yes, and a glass of port enjoyed with the Biffin is superb!

Incidentally, I wonder what Charles Dickens would have written about modern supermarket food?

Our two Norfolk Beefing apples before oven-drying

The apples wrapped in hay, ready to go into the oven

Wrinkly Biffins ready to be pressed

The finished, pressed Biffin

A bitten Biffin

Francis Pryor's Blog

- Francis Pryor's profile

- 141 followers