Francis Pryor's Blog, page 12

October 10, 2015

Sharing a Taxi with a Dead Ape

Most authors like to write and talk about the people, events and things that influenced or still affect their writing. Being somewhat vain, most of us choose to discuss aspects of life which made our work better, or which gave it its special atmosphere, or colour. Inevitably, we steer a bit clear of those personal tensions which may have embittered us, or given our writing a sour edge. But I don’t want to discuss such fundamental influences here. It involved me accompanying a dead ape, in Toronto, in high summer, in a taxi …

This short tale will also be about the circumstances that gave rise to the creation of one of the key scenes in my crime/thriller, The Lifers’ Club. As you will discover, sometimes the reality behind fiction can be stranger than anything your imagination can create. So our story starts in a low-key fashion, as most things did in those email-free, text-less days of 1969, with a phone call:

‘Hi,’ short pause: ‘Are you Francis?’

The voice was Canadian, as one might expect in Toronto, and although I was still relatively new to the country I knew better than to make a smart-arse reply. I had just enjoyed a good breakfast and was feeling relaxed. Soon my wife and I planned to walk downtown to one of the then fashionable ‘underground’ markets where one could buy tie-dyed t-shirts, expensive hookah pipes, water-beds and spicy food. The Vietnam War was at its height and Toronto had a huge population of US draft-dodgers. We had some good friends in that community. But I soon realised that our trip downtown was not to be.

‘Yes, I am,’ I replied.

‘My name is Englebert Humperdinck, and I’m a Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology. I was given your name by Doug. He said you were the kind of guy who wouldn’t mind doing something unusual.’

I should mention here that he was called neither Humperdinck nor Englebert, in fact I can’t even remember his voice, but I did hear that my name had been mentioned by my boss, the Chief Archaeologist of The Royal Ontario Museum, the late Doug Tushingham. I had just joined Doug’s department, the Office of the Chief Archaeologist, as a lowly technician and was keen to climb the ladder towards a full academic, or curatorial job. So if Doug had said ‘fly’ I would have flapped by arms.

The man on the phone went on to explain that he had just been told by a contact at Toronto Zoo, that when they had done the final inspection, late last night, they had discovered a female orangutan had died, probably of a heart-attack. They had taken her to the mortuary, where she was ready for collection. He then went on to explain that he had a few practical problems: they were short of staff; it was a weekend and Monday was a Public Holiday. To make matters worse, the Zoo’s chiller had broken-down and it was going to be yet another baking hot day in August. For a brief moment I couldn’t think why on earth he was telling me all this and then I suddenly realised: Vertebrate Palaeontology wanted her bones for their reference collections. He had been reading my mind:

‘You’ve gotta understand, Francis, she’s rare and we need her bones for our Reference Collection.’

I was about to reply along the lines of ‘Yes, orangutans don’t grow on trees,’ but thankfully thought better of it. He then arranged to meet me at his Department’s Biological Cleansing Facility, where he wanted me to deliver the ape and gave me the entire contents of the Facility’s Petty Cash box. His final words were succinct:

‘So I don’t care how you do it. Just get her here by Tuesday. And have a couple beers on us, when you’ve done.’

I watched as he strode out of the small courtyard, then I headed into the street. A few minutes earlier we had collected the Petty Cash box from the secretary’s office, where a calendar above her desk showed a tasteful picture of An Ape a Month. By some strange coincidence, August was Orangutan Month and we were treated to a close-up of an orange-haired female cradling an infant. It was very touching. Of course I knew a little bit about the Great Apes from my physical anthropology courses at Cambridge, but their bones gave me no idea they could be so charming. That calendar also taught me that the name orangutan derives from two Malay words meaning ‘person’ and ‘forest’. As I headed out in search of a taxi, I had visions of nimble, youthful orangutans swinging nimbly from branch to branch, like so many playful red squirrels.

There was only one yellow cab in the taxi-rank. The driver, who was in his later middle-age and enormously fat, was leaning back in his seat, snoozing. The windows were wide open and a newspaper lay across the steering-wheel. I coughed to gain his attention. He woke-up, shook his head and said in a North American voice, but with a strong hint of London’s East End:

‘Sorry, mate. Dozed-off in this ‘eat.’

He immediately recognised me as English and then mentioned that he grew up in Bethnal Green and had come to Canada after the war. The important stuff over, he asked me where I wanted to go. I explained my mission, fully expecting him to refuse, as it was more than a little outrageous. By rights, of course, I should have hired a small van, but life was too short and I hadn’t bothered to get a Canadian driving licence, as we didn’t yet own a car. Little did I then realise what a big mistake that short-sighted decision was to prove. He paused when I’d finished explaining.

‘Blimey, mate, got to hand it to you for cheek. Collect a dead ape, you’re saying?’

‘Yes,’ I replied, trying to sound as reassuring as I could, ‘She only died last night. So there won’t be any smell…’

He gave me a look which said that he’d seen and smelled things far more unpleasant in the War. Then he took a deep breath.

‘Money?’

I produced the wadge of notes I’d been given from the Petty Cash box.

His eyes grew round. At last he smiled.

‘OK,’ he said, ‘But not on this.’ He reached up and switched off the meter. ‘A hundred bucks?’

That was a big sum in those days. Quickly I leafed through the notes. I could just do it.

‘OK,’ I replied.

‘And in advance.’

This was said with what he hoped was a disarming smile. I felt neither charmed nor won-over, but I had no alternative. So I paid-up. Desperate times call for desperate measures.

***

Toronto’s world-renowned Zoo sits on the edge of the great city, which sprawls along the northern shores of Lake Ontario. As we drove away from the lake along Yonge (pronounced ‘Young’) Street, the city’s principal thoroughfare, one could occasionally catch glimpses of gleaming water through the shimmering damp heat-haze of high summer. In Britain we think of Canada as cold, but in actual fact Toronto is 500 miles south of London and their summers are a great deal warmer – and steamier – than ours. I hadn’t been this far from the city centre before, and the taller buildings of the downtown banking area looked magnificent – a miniature New York set on the edge of what seemed like an inland Atlantic Ocean.

I think I must have drifted off – it had been a frantic and rather tense-making morning – when I was rudely awoken by a sharp tap on the window. It was a uniformed security guard. I read him the details of the man we were to meet at the Mortuary. He went back into his booth and I could see him pick up a phone. The he reappeared and gave the driver instructions. By now I was feeling so relieved: we were nearly there. Soon it would all be over. But little did I know.

We followed his instructions and when we got there, the Zoo’s Mortuary turned out to be a surprisingly unimpressive building. Admittedly it was on a weekend, but there were no scurrying vet-nurses in green head-to-toe overalls, as one might expect today. Instead there was a bell, which the driver managed to push – I had never seen such a long, fat arm – without leaving the cab. Then we waited. And waited. In the distance we could hear unusual shrieks and catcalls which sounded more like a school for the kids of hyper-active comedians than a zoo. Or maybe I’m being unfair. But it was odd, disarming and a little creepy, given where we were parked. After what seemed like an eternity, during which time my driver successfully ignored all my attempts at small-talk to lighten the mood, a door to the left of the one we were waiting by, opened, and a man in ordinary workman’s overalls beckoned us over. Slowly we drove the few yards to meet him. Just around the corner of the building was a pair of double-doors, which were then opened from the inside. We drew-up alongside them.

I don’t make a habit of visiting mortuaries, but like everyone else, I do have certain expectations. I wasn’t anticipating somewhere evil at all, but I had hoped for a slight element of fear, regret or sadness; a cool-to-cold atmosphere; sympathetic, if silent, staff and everywhere the powerful aroma of disinfectants.

But this place more resembled the delivery bay of a small engineering works in one of the new industrial suburbs that were then springing up around most of the cities of the western world. In the background I could hear a radio, tuned-in to CHUM-FM, a popular local acid rock station, and two men were sitting at a table drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes, surrounded by fuse boxes and the usual paraphernalia of a workshop. I began to doubt whether we had been shown the right place at all. It wasn’t remotely like a mortuary, although come to think of it, there was a strong smell of disinfectant. Rather hesitantly I gave one of the two men the piece of paper with the reference number I had been given at the Museum. He glanced down at it. Then took a sip from his coffee. A puff on his cigarette. All the time in the world. I could feel my palms starting to sweat – and it wasn’t just the heat.

‘You from the Museum?’

This was asked in a Scottish Canadian voice.

‘Yes, I’ve, I’ve come to collect…’ I couldn’t think of the right word, ‘to collect a specimen. It’s for the Department of Vertebrate Palaeontology.’

In my experience long words could often open closed doors. But not today. He said nothing.

There was a further long pause while he finished his coffee. Eventually he looked up:

‘You’ll have to give me a hand.’

I glanced at the other man who was reading the sports pages of the newspaper. He studiously ignored me and remained sitting at the table.

We walked across to the double doors and my taciturn companion looked right and left. Then he turned to me:

‘Where’s the truck?’

‘There isn’t one.’

For an instant a look of incredulity flashed across his otherwise inscrutable face. But sadly it didn’t set me thinking.

‘So it’s the cab?’

I nodded.

‘That’s right.’

I detected a faint exhalation and a slight upwards glance. By now I realised he was acting oddly. He didn’t think it was going to work. But I was still quietly confident. For a moment I could see orangutans swinging nimbly through the trees. Everything was going to be fine. Of course it was.

We went back into the building, where the second man was still reading his newspaper, but this time we crossed to the opposite corner and entered a smaller pair of more hospital-like double doors, which swung shut behind us. He turned on the lights to reveal a featureless corridor with another pair of swing-doors at the end. Just in front of the far set of doors was a stainless-steel, heavy-duty trolley, whose blankets concealed something the size of a small cow. Maybe a young moose or an antelope, I speculated as I walked past. For a moment I waited in front of the second double-doors, for my companion to open them. Then I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned round, suddenly with a feeling of cold foreboding. As I watched, he pulled the blanket off the trolley to reveal a vast expanse of dark brown skin and orange hair. I was stunned. Far from swinging through the trees, this female could have uprooted them.

***

As a sheep-farmer I’ve long been aware that animals have a certain dignity in death. OK, the Church may say that they don’t have souls, but then it’s not unusual to hear rubbish from a pulpit. And if anyone had a soul, this poor dead orangutan had one. Her dark eyes, which were wide open, if somewhat clouded, seemed to look at one in a strangely disengaged fashion. It was as if she was observing me: she was now the anthropologist and I was the ape. I hadn’t appreciated until then how high an ape’s eyes were set in the skull and there was – or did I imagine it? – a distinct change between the hair on her head and the rest of her body. Like many middle-aged and elderly humans today, she was generously proportioned, but there was nothing unfit about her. Her muscles were massive and had plainly been used. I don’t think she’d have looked odd pushing a vast supermarket trolley in some simian Sainsbury’s. And I’m absolutely certain she would never have worn tight leggings and horizontal stripes. But she was vast. Could we fit her in the taxi? And if not, what on earth was I to do?

The two of us pushed the trolley out onto the forecourt and up to the taxi. The driver had the window down. He lowered his newspaper – still on the same sports’ page – and stubbed out his cigarette. But did he open the door? Did he, Hell!

We pulled off the blanket and as we did so, I glanced across at the driver, who showed no emotion whatsoever. We could have revealed a trolley-load of spark-plugs and spanners for all he was concerned. Eventually he offered advice:

‘It’s a big’un. You’ll have to lift out the back seat. Then stick it in the trunk.’

How that ‘it’ irritated me! I also remember thinking he’d been in Canada long enough to say ‘trunk’ for ‘boot’. But he didn’t offer to help us. I thought for one awful moment that my only practical assistant was going to return to his companion at the table. But he decided against it. In hindsight, I think he was beginning to enjoy himself.

Together we removed the rear seat and squeezed it into the boot. Then, rather ingeniously, by partially lowering the shelf of the trolley, which was secured by butterfly-bolts, we slid the dead ape into the cab, which tilted quite dramatically at the impact. At that, the driver must have turned on the ignition, because an internal alarm sounded. He poked his head out of the window and announced:

‘Uneven load. The cab won’t start unless you shift it.’

That ‘it’ again. I was beginning to get annoyed.

But the driver didn’t care. He was reading the damn newspaper.

After much straining we managed to man-handle the poor creature across to the cab’s nearside. When we had wedged her upright, I shut the door. Sitting so very low down in the vehicle, her huge head was at the same height as a human’s. Standing on the outside looking in, I found it spookily strange. To make matters worse, she was staring out of the window. This made my companion smile. I could see he had the Scots’ dry sense of humour, but I suddenly became very aware that her vast and unearthly gaze would terrify any passing pedestrians, especially when we drove through the crowded streets downtown. So I went round to the other side, reached in, and gently angled her head towards the front. Somehow that looked a little less odd.

The driver didn’t want her to or roll over, as that would set-off the Uneven Load alarm again. And in those days cabs weren’t fitted with seat-belts. So I sat next to her on a pile of collapsed cardboard boxes that we had to fish out of the garbage skip. For some reason they smelled strongly of garlic, which I didn’t object to (a) because I’m very partial to it and (b) because all the manipulation had caused our dead companion to release the preliminary gasses of putrefaction – which were neither pleasant, nor unexpected, given the heat and humidity of the day.

I slipped the helpful Zoo assistant enough money for a few beers and we set off back to the Museum. And then something very odd happened. The driver suddenly started to act like a cabby: all cheerful questions and banter about local politics, beer and the Toronto Maple Leafs. I fully expected him to say something chirpily sexist to our dead companion. But strangely, he didn’t. I’ve never been much good at small talk, but in this instance it helped keep my mind off the problems at hand – which were about to get critical.

We came off the fast freeways that skirt the metropolitan area and joined Yonge Street, which in its uptown stretches is dual-carriageway. As we bowled along I found I was thinking about that rather strange name: Yonge. I’d just learnt from a friend in the Department of Canadiana that Sir George Yonge was an expert in Roman Roads and was a friend of John Graves Simcoe, the first colonial administrator of Ontario, who named the street after him in the 1790s. Anything to keep my mind off the dead ape beside me – and the increasingly dreadful smell. I’d always been led to believe that after a few minutes your nose gets used to powerful odours, and they vanish. But that hadn’t happened to me. Not even slightly.

By now, the buildings we were passing by were becoming older, larger and closer together. There were more people on the sidewalks. But still the happy cabby continued the brainless chatter. I’d completely given up trying to respond. It was pointless: he was on a looped tape. At the mid-town junction of Yonge Street and St. Clair Avenue, we paused briefly to allow a tram, complete with ringing bell, to pass in front of us. Then we headed down the hill, presumably the Ice Age shoreline, towards the lake, the Museum and downtown. At this point the burble from the front started to break-up and fade. He’d remembered something. I could see him glance at his watch. Then rapidly he reached across and switched on the radio. He’d nearly missed it: the big game. Toronto Maple Leafs, I think. Or were they ice hockey? Doesn’t matter.

My driver was obviously a big football fan and the sound of the radio in the background wouldn’t normally have intruded – in fact I’d have welcomed it, as it did signal an end to the chatter. Unfortunately, however, along with the chatter seemed to go his concentration. His mind plainly wasn’t on the job at hand. Up until just south of the second major mid-town junction at Yonge and Dundas his driving had been smooth. He had seemed to be aware that he was carrying a huge and unstable deadweight; so he made allowances: no swerving, no rapid braking, nor acceleration. Then that bloody game began in earnest.

I was also becoming aware that two other factors were about to compound my problems. The first was geographical. We were now on the fringes of the late 19th Century city. From here on, Yonge Street was two-way, albeit with two lanes in each direction, and there were traffic lights at roughly every other block. The second was chronological. It was August, and the blanket of anonymous darkness was still several hours away. We could be clearly seen from the sidewalks. To make matters even worse, it was now early Saturday evening and people were heading out for the pubs, restaurants and night-clubs of downtown. It was only too apparent that many young men had already enjoyed several beers, doubtless in the knowledge that tomorrow was ‘dry’: pubs closed and churches opened in the quest to reap the Sunday dollar. I must add that today onetime prim and proper ‘Tory Toronto’ is very different – in fact it’s the gay-scene capital of the Eastern Seaboard. But not in 1969: in those days you made the most of your Saturday nights.

By now we were in the heart of downtown, but at least traffic was moving. Once or twice, when we had to slow down, I think I might have spotted the odd nudge or pointing finger, as people on the sidewalk caught glimpses of our cargo. But they probably thought we were heading out for a fancy-dress party. Then I noticed the driver’s head twitch: the quarterback was making a break. The crowd roared. He threw a thirty yard pass. Wild cheering from the crowd – and the driver. A few seconds later: touchdown! The stadium went wild, The driver punched the ceiling with both hands and the cab lurched across into the fast lane. But the lights were red. So we squealed to a standstill. The ape had collapsed forward, over the front passenger seat. And there was something slightly unpleasant drooling from her mouth.

Why is it that when you want a car of deaf-blind pensioners to draw-up in the nearside lane, you get a bus-load of eager students? Because that’s what appeared alongside us, just as I was pulling the poor ape back from over the front passenger seat. And as we had discovered back at the zoo, her head lolled naturally towards the window, where the bus-full of students were treated to a clear view of her huge face, cloudy eyes and drooling mouth. I’m pretty sure it was too much for them, because for a brief instant I thought we had got away with it – as there was silence. But it was very short-lived. Suddenly all hell broke loose. It was a hot day, the bus windows were open and you could have heard the screams right across Lake Ontario in Rochester, New York State. In those days most cars didn’t have air-conditioning, so everyone’s windows were open. After a few second I glanced in the mirror: several cars back, people were opening their doors. And getting out. Horns were blaring and the screams were getting worse and worse. But my driver was blissfully unaware. One or two people had started to head towards us from the sidewalks And they were looking menacing. Things were beginning to turn nasty. Then, mercifully, the lights changed. I held my breath – but we didn’t budge. The driver’s brain was still with the Maple Leafs in that bloody stadium.

In desperation, I politely nudged his shoulder – again, desperate times call for desperate measure – and thank God: it worked. He drove away, as if nothing had happened. No roaring engine; no squealing tyres. But we had escaped. Out of the back window I could see the pandemonium we had left behind us. All vehicles had stopped. Pedestrians were everywhere. A few people looked and pointed in our direction, but no cars followed. It had been a close-run thing.

I sat back and closed my eyes. My body had relaxed, but my mind was still in a whirl. Then I found myself wondering how many future students would know anything about the colourful post-mortem history of the bones they were handling in the Reference Collection? To them, they’d just be yet more dry, white specimens, this time of the female orangutan, Pongo abelii. I smiled at the memory of her name as I looked down at the collapsed and festering bulk of my vast companion. Poor Pongo. At least she was about to find a certain odourless immortality in the Museum. And me, how did I feel about it all? To be quite honest I was completely knackered. Forgive the weak pun, but I couldn’t have given a monkey’s.

October 9, 2015

Archaeology Podcast Network

My recent crowdfunding campaign has produced some interesting spin-offs, including this trans-Atlantic podcast in which I am interviewed by two colleagues in the United States. It was great fun to do – and I think that comes across quite well. Click and enjoy!

October 4, 2015

Reaching New Readers

As part of the final run-in for The Way, The Truth and The Dead, I’ve done two guest blog posts about crowdfunding (and, yes, “crowdfunding” is now generally preferred to the more correct, if clumsier “crowd-funding”). Both have been aimed at an archaeological audience, as both the host blogs are quite specific about their targeted readers. Both my pieces approached the topic from a personal, historical perspective. The first stressed the potential of crowdfunding, whereas this, the second, is more general. It’s about seeing the past as an essential component of the present – and, by implication, the future. If we archaeologists have a problem, it’s that we’re too reluctant to throw aside our discipline’s self-imposed blinkers: sometimes over-focus can destroy the imagination. And that worries me increasingly. But see what you think. As before, click on the link.

Reaching New Readers

Sometime in the winter of 1990, I think it was after Christmas, I went to London for a meeting with the Commissioning Editor of the Publisher B.T. Batsford who had formed a partnership with English Heritage to launch a joint series of archaeology books. To my surprise they wanted me to write one about Flag Fen, our waterlogged Bronze Age site, on the Fen-edge of eastern Peterborough, which we had discovered nine years previously. Since then we had opened our excavations to the public and were currently welcoming over 20,000 paying visitors a year. And we tried to do the job properly. Glancing through an old leaflet from this time, I note that we were sponsored by some large corporations and were registered with the English Tourist Board as ‘A Quality Assured Visitor Attraction’, no less. But it was very hard work. Most members of the team worked six-day weeks and for about a decade we very rarely had a weekend off. That fact alone gave one’s life an interesting rhythm, which I still look back on with some nostalgia.

I find it hard to believe now, but I was very surprised by the new commission…

September 26, 2015

Crowdfunding: freedom, frustration or fantasy?

Originally posted on Doug's Archaeology:

Originally posted on Doug's Archaeology:

Crowdfunding in archaeology is something I am interested in and have blogged about a couple of times (see Tracing Finds: A Case Study in Crowdfunding Archaeology, Are Crowdfunding Platforms Worth it?, Fairy Godmothers Do Exist- Crowdfunding Archaeology, You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger! The Money of Crowdfunding Archaeology and Heritage, Crowdfunding Archaeology- a view from the trenches, Crowdfunding Archaeology some Data, Finally!). I have also interviewed the DigVentures Crew for the CRM podcast. I was lucky enough to have Francis Pryor volunteer to discuss some of his experiences with crowdfunding publications. Francis is currently in the process of crowdfunding a book- The Way, The Truth and The Dead. and he is 81% towards his goal- hint, hint, nudge, nudge. Without further delay Francis’ thoughts and experiences with crowdfunding:

Crowd-funding: freedom, frustration or fantasy?

It’s funny I should be writing a post on crowd-funding…

View original 2,274 more words

September 3, 2015

Time for the Final Push

My second Alan Cadbury mystery, The Way, The Truth and The Dead is now 73% funded and it’s time to launch the final push. MANY thanks to everyone who has subscribed: you’re all stars! And if it’s not too much trouble, can I ask you to forward this blog post to your friends – who knows, it may whet their appetites? And any web-based support (FaceBook, Twitter etc.) would be much appreciated. I’m determined to have this book funded before winter sets in. Of course if you haven’t yet subscribed, it’ll cost you £10 for the ebook or £24 for the hardback (incl. post and packing). There are also more expensive options ranging from a signed copy (£50) to an intimate evening with Alan Cadbury (ha-ha). Click here and a have a debit or credit card handy.

When authors publish extracts they are often taken from early on in the book, as I did previously, but this time I thought I’d find something further on, when the plot was starting to darken – and thicken. At the same time I wanted to dispel the common myth that archaeology is just about digging and finding things. It isn’t: most of a professional archaeologist’s time is spent on the phone, filling-in grant application forms, talking to specialists or writing reports. This extract, which starts a new Chapter, is based on many such conversations I’ve had with specialists. And like one or two I’ve had, it takes place early in the morning and Alan has a slight hang-over. Sounds familiar? Now read on…

Alan’s dream began to disintegrate. Bleating sheep were scattering as the scarlet fire-engine, all bells and sirens at full blast, hurtled towards them. He knew he was about to die. Horribly. He was gripped by panic; then slowly his brain woke up. It was the phone. The bloody phone. Last night he’d been too tired to turn it off. He reached out and picked it up.

His sleepy eyes wouldn’t focus on the screen.

‘Hello?’

He hoped it wouldn’t be from a call centre in India. He didn’t want to be rude to some student trying to earn a living.

‘Alan,’ the voice was half-familiar, ‘It’s Alan, here.’

Alan? Alan? For an instant his woolly brain thought he was going mad. Then sanity returned: it must be Dr. Alan Scott, the soil micromorphologist in Cambridge. Earlier in the week he’d watched while Dr. Scott hammered sample tins into the still fresh face of the trench section, directly over Grave 2. Alan (Cadbury) thought these in situ samples might throw light on when the grave had been dug, relative, that is, to the start of the later Roman alluvial episodes. In other words, he wasn‘t expecting the equivalent of a radiocarbon date, but it could provide them with a reliable approximate picture. Both Alans had long been great believers in the power of soil micromorphology.

It had taken Dr. Scott several days to prepare and grind-down the thin sections before he was able to examine them under the high powered microscope. But he was clearly delighted with the results.

‘I finished last night, but thought you wouldn’t welcome a call so late, as I know you’ve been quite busy these evenings.’

‘Yes, it’s been a bit frantic.’

‘And last night’s was good. We had it on in the Lab. The students cheered when the skull appeared. And that Tricia has won-over the blokes, big-time. You’d better watch it Alan, or she’ll up-stage you, unless you’re careful.’

‘I hope she does. I think she wants a career in TV, which is more than I do. But the samples?’

Small talk. He hated it.

‘Oh yes, the samples. Well, for once I think we took them from the right place and the sequence doesn’t seem to have been disturbed too much by post-depositional effects.’

‘Ah, that’s good. So not a lot of drying-out?’

‘No. So I think we’re deep enough down to be able to say some useful things.’

‘Like?’

Alan’s sleepy mind had now fully woken-up. He wanted Dr. Scott to get to the point.

‘There’s a clear cut-line in the lower part of the alluvium’

‘Yes, when we were digging we could see a very faint change in colour, which lined-up well with the edge of Grave 2. Is that what you spotted in thin-section?’

‘It is, I’m certain of that. And the other thing that’s very clear are the separate episodes of flooding, which form a series of quite distinct varves, about half a millimetre thick.

This was music to Alan’s ears. He’d first learned about varves when studying the history of archaeology at Leicester. They were first identified in Scandinavian glacial lake-beds in the 19th Century. But soil scientist Alan hadn’t finished:

‘I couldn’t spot any obvious standstill or weathering horizons, so I must assume the flooding was a regular annual event. And you say the pottery dates the start of alluviation to the later third century?’

‘That’s right. Sometime shortly before AD 300.’

‘Well, in that case the grave-cut was made some 15 centimetres, say three centuries of flooding episodes, later. I’d guess sometime between AD 600 and 650 – certainly no later.’

‘And presumably flooding continued?’

‘Well, no. There’s a standstill horizon almost immediately after the cutting of the graves.’

‘Any idea how long that was?’

Dr. Scott took a deep breath.

‘That’s difficult to say. Maybe two or three centuries? Then flooding recommenced, but worse than before. This time the varves are at least twice as thick.’

‘Does that sound to you like they’d introduced flood-control measures? Maybe a cemetery wall, or improved local drainage?’

‘I’d go for the drainage,’ Dr Scott replied, ‘Walls tend to collapse, whereas drains were maintained.’

‘Yes,’ Alan was thinking aloud, ‘That certainly fits with the archaeological evidence. And we know the early monastic communities were keen to drain. It gave the Brothers something useful to do.’

That wasn’t quite fair, but what the hell. Alan felt elated. That call was just what he had wanted to hear.

Behind the scenes on a ‘live’ TV excavation.

August 27, 2015

We’re Opening the Garden in 2016!

When you open your garden to the public it’s important to do it right, especially nowadays when people can be so litigious. So you must have all the appropriate insurances etc. in place. We open for charity and so we’re doing it through the National Gardens Scheme (NGS) – a wonderful organisation that raises money for charities, mostly to do with welfare and medicine (eg MacMillan Cancer Support). The NGS’s roots lie in the birth of ‘civilian’ (i.e. District) nursing, which began in 1859, and the NGS was set up in 1927 as a fund-raising idea. Volunteers were asked to charge ‘a shilling a head’ for admission to their gardens and four years later, in 1931, the up-market magazine Country Life produced for them a catalogue of open gardens, which was (and still is) known as The Yellow Book, because of its bright cover. And the idea soon caught on.

The NGS makes opening easier for people like us, by providing experience and practical advice, plus a package of posters and useful signs to the Car Park etc., and of course insurances. The Scheme is organised by county. So last week our garden was inspected by one of the Lincolnshire team whose job was to check that their high standards of horticultural proficiency were met; she also kept an eye out for potential health and safety problems, such as revolving knives, loose paving and flesh-eating toads. I’m glad to say that our garden passed this test. So we’ll be advertised in The Yellow Book for 2016. We haven’t fixed the precise date yet, but it’ll probably be a Sunday in later September.

We have actually opened the garden for the NGS on two occasions previously, in June 1999 and 2000. In those days we weren’t quite so busy and had the energy to cope with lambing in March, plus hay-making in June/July. June is the month when almost any garden is at its best and it’s the month when most of The Yellow Book gardens are open. ‘The July gap’ is infamous in gardening circles, as the first flush of roses has finished and the perennials and shrubs of high summer haven’t come into their own yet. July’s quieter, but then there’s another flourish of openings in August. Although our garden is at its most colourful in June – and Maisie’s collection of old roses is superb – many varieties have a second flowering in later September, which is when Asters come into bloom and grasses put up their showy seed-heads. There’s also a hint of colour in birches, yellow alder and field maples. The weather, too tends to be more predictable and less wet than June or August. Our last opening, on June 18th, 2000, was ruined by torrential rain, which actually left part of the main border under water! I think we managed to welcome about a dozen visitors that year.

After the debacle of 2000 we decided to put garden opening on hold and this coincided with Maisie doing a lot more commercial work with prehistoric wood (these were the years of rapid expansion prior to the bankers’ bubble of 2007/8), while I was writing books (Britain BC, Britain AD, Britain in the Middle Ages, and The Making of the British Landscape) and, of course, doing three mini-series of my own, plus dozens of Time Teams for Channel 4. But in the past three years things have calmed down, and although 2000 was a minor disaster, we did benefit from the business of opening to the public: it gave purpose, direction and discipline to our work in the garden. And we also got to know a number of new friends, some of whom had opened their gardens for the NGS, too. And of course the Open Day itself is rather like a big party and it’s great when old friends muck-in and help at the pay desk and in the tea room (or barn!). I remember our first opening, in 1999, put me very much in mind of one of our Open Days at our big excavations in Peterborough in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, with a full car park, plenty of adrenalin during the event, followed by lashings of food and drink around the barbeque.

If possible we like to have a few plants to sell to our visitors, especially if they’ve enjoyed them in the garden. For example, we use Euphorbia myrsinites, the blue or myrtle spurge, along the fringes of our better-drained beds in the front garden. This was where the builders (on our suggestion) tipped all their broken cement fragments, smashed tiles and bricks, not to mention lots of sand and gravel – and consequently it’s the only part of the garden that’s at all well-drained. And those are precisely the conditions favoured by myrtle spurge. So yesterday before we were hit by the forecast thunderstorms I nipped out and potted up seedlings that had sprouted around the edges of the gravel pull-in leading to our back door. I found 23 and potted them up – and with luck I should get a few more later in the autumn. What do you reckon: £2 a small pot and £3 for a larger one? That’ll appear very cheap next year.

Potted-up seedlings of Euphorbia myrsinites, the blue or myrtle spurge. When they go on sale on our Open Day in September 2016 (note: not 2015!) they’ll be twice the size.

Then a couple of days ago the rain started and I began to have doubts about the whole Opening idea. Maisie was away at the University in York, poring over ancient timbers. So I was alone with my anxiety. Just to reassure myself, I ran upstairs and took a picture of the garden; then I down-loaded it onto my main computer and peered at it critically on the large screen. Was the garden up to standard? Was it? I was far from certain. In an introspective, gloomy frame of mind I Tweeted it – and was astonished by the kind responses it received. Anyhow, you can judge for yourself, below. So I’m feeling a bit calmer now. And many thanks to my Twitter friends for those warm words. Tonight I’ll go to the Peterborough Beer Festival with a very old gardening friend whose palate, like mine, is unrivalled. To drown my sorrows? No, I no longer have any!

The view of our garden from an upstairs window, in late August, 2015.

July 29, 2015

Our North Wales Break, Part 2: Gardens (or Size Isn’t Everything)

A good holiday should make you think. I’ve never really been very set on the idea of using your holiday to ‘escape’ – but from what? From your normal daily life? If the answer to that is yes, then I’d suggest you should be looking for a more permanent answer. I also don’t take a holiday to see places and visit cultures that are completely different from the people and places I’m familiar with in my daily life. I did that when I was younger. These days I’m more interested in seeing things that are just a bit different. I suppose it’s all about subtlety. Put another way, on holiday I hope to discover new ways of looking at, and thinking about, life in general. To my mind, a good holiday should enrich your appreciation of the way you live for the rest of the year. It should give you new ideas and add a much-needed dash of enthusiasm when familiar surroundings and the tasks of the day seem a little tired, and a bit ordinary. This can work at two levels: at the general and the particular. So in this post I’m going to be thinking about some of the gardens we visited and how they might affect the way we manage our own garden at home. And I plan to do this mainly through pictures rather than words. Cue the first picture:

The double herbaceous border at Arley Hall, Cheshire.

The double herbaceous border at Arley Hall, Cheshire, is one of the glories of the British country house garden. It is also one of the earliest, appearing on a garden plan of 1846. We had long planned to visit, but sadly Cheshire is a pig to reach from south Lincolnshire, especially when the roads are as crowded as they are these days. But it was well worth the effort. A team of about half-a-dozen gardeners refresh the borders every winter and make hazel frames for the taller plants, which are soon covered-up in the spring. It’s an extraordinary task to have to do every year, but it does allow for subtle changes and improvements. Certainly the borders at Arley had a life of their own and did not feel at all over-designed and somehow institutionalised, as do some of the borders in country house gardens run by big national institutions.

One side of our own mixed (shrubs and herbaceous perennials) double border.

As we drove home I couldn’t help wondering whether our own herbaceous borders would look very drab when set alongside Arley. But when I got home and strolled round the garden the next day, I was quite encouraged by what I saw – and smelled. Although the scale of the two gardens was so very different the borders worked in their own, different ways. The Arley borders were more formal and far deeper than ours, but not being burdened by so much distinguished history, we allowed ourselves the luxury of mixing-in roses and other shrubs, such as Philadelphus which provided both height and scent. More to the point, a sprinkling of grasses and shrubs does cut down hugely on the dividing-up and splitting of herbaceous perennials in late autumn and winter. We’re also lucky, given our heavy fen silts, to be able to grow the Day Lily, Hemerocallis, and these don’t need constant division to rejuvenate. They really make the small border come alive in the late spring, right through to high summer.

Our small mixed border, with the Hemerocallis ‘Hornby Castle’.

The gardens at Bodnant, near Colwyn Bay, Conwy, are extraordinarily beautiful and varied. Laid out by the same family (plus a remarkable dynasty of gardeners) since 1874, the gardens exploit the dramatic rise-and-fall of the natural landscape, while at the same time including some remarkable set-pieces, such as rose terraces, pergolas and the wonderful use of both still and flowing water. It’s also a plantsman’s garden and contains a huge variety of unusual trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants. Although we were there for a full day, we didn’t manage to see half the garden. Instead, we concentrated on the more formal areas closer to the house.

I don’t think any garden feature I have ever encountered has made such a big impression on me as the rose terraces and pergolas at Bodnant. The scent filled my head and the soft colours were warm and comforting. They never jarred nor clashed. Many of the roses were bred by David Austin whose new varieties known as English Roses have re-introduced scented flowers, with softer, more pastel colours. The flowers themselves stand-up to rain far better than old varieties which were often washed-out after a short shower. We grow several of his English varieties.

The ultimate in formal gardening: the lower rose terrace at Bodnant Gardens, Conwy.

I often think the way gardens handle water is a good indication of their quality and Bodnant scored highly here. I particularly liked the formal-yet-informal Lily Pond with the house, itself no architectural jewel, sitting pleasingly in the background. It was impossible not to feel relaxed here.

The Lily Pond, with the Lily Terrace and Bodnant Hall in the background.

I know it’s ridiculous to compare our amateur, run-on-a-shoestring garden with places like Bodnant and Arley, but any gardener worth his or her salt cannot visit another garden without drawing some inspiration for their own garden. And our visit to these two great gardens confirmed our belief that even a low-budget rural garden must have elements of formality to give it cohesion. With us it’s all about clipped hedges and a few garden structures, most of which are fairly home-made from stuff you can get at garden centres. I like to make shelters and suchlike from posts and trellis. On the whole I try to steer-clear of things that are ready-made. One exception is a superb wirework four-way dome, which was given to us by my brother Felix as a house-warming present some twenty years ago. Felix’s dome now sits in the small cottage-style front garden which we are at last trying to knock into shape. The trouble is, the soil was puddled and damaged when the house was being built, back in ’95, and we’re always having to remove broken roof tiles, bits of concrete and rubble. But I think at last we’ve got the ground into better heart. Anyhow, last winter Maisie had the idea of incorporating the wirework dome into a more formal central path, part gravel and part stepping-stones, which led up to a small urn. Here’s a view of that path taken from the gate that leads through to the Pond Garden (our pond is just a puddle compared with Bodnant!). But I’ll return to Felix’s dome shortly.

Formality Fen-style: the path through our front garden.

In my last blog post I featured the extraordinary Victorian pseudo-castle at Penrhyn, but I didn’t say that it’s surrounded by a remarkable garden of quite considerable charm – and well worth a visit. A particularly successful feature was a Fuchsia arch walk. Now arch walks are something of a speciality in British gardens and most often feature Laburnum (as at Arley, for instance) or sometimes Wisteria. But at Penrhyn they use Fuchsias. Admittedly their Fuchsia arches are a quarter the size of the giant Laburnum walk at Arley, but then the flowering season is very much longer (all summer and most of autumn). And besides, garden features don’t have to be big to be beautiful. Setting is important for such features and the Penrhyn arches were set alongside a superb bog garden which is currently being restored. I do hope the restoration (which slightly ominously will feature children’s dipping platforms) does not tame or suburbanise it too much. I loved the massive and very wild-looking Gunneras.

The Fuchsia arch walk at Penrhyn Castle, Bangor.

Sadly our ground is too wet for Laburnum, but we can grow Fuchsia very well and being quite close to The Wash we are spared the harshest winter frosts, unlike many other gardens in eastern England our Fuchsias are rarely cut to the ground. So last year Maisie started weaving Fuchsia stems into the wirework of Felix’s dome and rather to our surprise the effect worked and the Fuchsias looked very good alongside the Clematis texensis ‘Princess Diana’. Sustaining interest from summer into autumn is always a problem, so we plan to make greater use of trained Fuchsias in the future.

Hardy Fuchsias trained up a wirework arch dome in our front garden.

And finally… No holiday would ever be complete without a surprise, and ours came when we visited the National Trust property at Plas-yn-Rhiw on the southern shores of the Lleyn Peninsula. This charming Georgian (and earlier) farmhouse sits in a sheltered spot on the hillside overlooking the bay of Porth Neigwl, or Hell’s Mouth, which aptly describes the weather here in the stormy times of the year. In the last century Plas-yn-Rhiw was owned by three remarkable sisters of the Keating family, who restored the house which has become something of a time capsule of the ’50s and ‘60s. The sisters loved art and archaeology and I spotted two woodcuts by my great-aunt, Gwen Raverat (best known for her book Period Piece), and an excavation report on Coygan Camp by an old friend, Geoff Wainwright, published in 1967. I’m not sure he’ll be over-pleased to discover that he has become something of a museum piece. The youngest sister, Honora Keating, who owned Geoff’s book, also wrote an erudite, but very readable and fully illustrated account of the house and garden in 1957, which quite rightly has been reprinted ten times – the last in 2011, by the National Trust who still sell copies at a very reasonable £2.00. It’s worth ten times that.

The sisters also created a stunning garden. I hesitate to use the word, but it was a very feminine creation: intimate, warm and modest, but all done with superb panache and a profound understanding of plants. I’ve always loved it when gardeners ‘borrow’ views of the surrounding countryside and incorporate them into the garden. The landscaped park was frequently borrowed at Arley, for example. But at Plas-yn-Rhiw the view across a small terrace garden out across Hell’s Mouth was literally breath-taking. It proved that good gardening is indeed about art and inspiration; it is not just a craft. I will never forget that scene.

The view from the gardens at Plas-yn-Rhiw, on the southern Lleyn Peninsula, towards the coast at Porth Neigwl, or Hell’s Mouth.

July 25, 2015

Our North Wales Break, Part 1: Buildings (and sheep)

Maisie and I have decided that we’re not great ones for long holidays. We prefer to take three or four day breaks instead, and this year we decided to visit north Wales. Maisie was keen to see the well-known garden at Bodnant, while I wanted to photograph Caernarfon Castle (Gwynedd), with its famous striped masonry. And after having kept Lleyn sheep for over twenty years we both wanted to see these wonderful animals munching grass on their home turf, the Lleyn Peninsula.

The break was a great success. It rained a bit, but not as much as we feared (statistically Wales has vastly more rainfall than the Fens), and the sun shone. Our cottage, the gateway lodge of the ancestral home of the Armstrong-Jones family, and now a fine country house hotel, Plas Dinas, near Caernarfon, was very reasonably priced and extremely comfortable and well-appointed, as they say in the leaflets. Although it was close to a road, the traffic noise was minimal. We certainly plan to go back there in the future when we’ll give the fine dining at the main hotel, down the long wooded drive, a taste. Sadly, this time we were far too busy. And we’d also brought lots of fresh vegetables we’d grown ourselves. I’ll say a few words about the great gardens we visited in my next blog post; right now I’ll concentrate on buildings.

One of the pleasures of visiting great gardens is discovering unusual antiquities, sometimes concealed within them, often as picturesque ruins. But at Arley Hall in Cheshire, just across the English border, the surprise wasn’t concealed: it was right there at the main entrance. In fact it was a popular venue for weddings. So was it a church, a chapel, a temple even? No, it was none of these things. It was a seven-bay timber-framed cruck barn, built around 1470. The so-called crucks were huge curved vertical supports which stretched from just above the floor to the apex of the roof in a vast soaring curve. I never visit a cruck barn without feeling elated – and Arley’s was no exception – it must be a great place to get married.

The great cruck barn at Arley Hall, Cheshire.

The next building was the first one we visited in Wales: our cottage, the Gatekeeper’s Lodge at Plas Dinas on the southern approaches to Caernarfon. It wasn’t particularly spectacular, but I do like Arts and Crafts houses. Unlike so many modern houses, they’re always laid-out unpredictably, often with staircases where you’d least expect them. And this one was no exception. I don’t know what date it was built, but I’d guess it was quite late, but undoubtedly pre-1914. As we drove around we couldn’t help noticing that many of the rural buildings in that part of Wales were Victorian or Edwardian and they date to the period when monied and not-so-rich people wanted to live amidst spectacular scenery, but I’ll have more to say on this shortly.

The Gatekeepers Lodge, Plas Dinas, near Caernarfon.

The big attractions in this part of Wales have to be the great castles at Conwy and Caernarfon, built by King Edward I in the 1280s – a staggeringly long time ago. Both buildings were meant to be symbols of English power and both dominated walled towns which were in effect English boroughs. I discuss Conwy, especially the walled town, at some length in The Making of The British Landscape. Both castles were designed by Edward’s master mason – today we’d call him an architect – James of St. George, who was actually a Frenchman from Savoy and learnt his trade building castles in his homeland in the 1260s. Both Conwy and Caernarfon are now World Heritage Sites. Caernarfon is famous for its polygonal towers (most towers and turrets of the time were round) and the striped masonry of its walls was certainly intended to impress. Historians have suggested the stripes echoed the walls of Constantinople, or alternatively Roman towns in Britain. I honestly don’t think it matters which, because it’s still abundantly clear that Caernarfon was intended to impress and over-awe. It’s a symbol of power – if ever there was one.

Caernarfon Castle, from across the port and River Seiont.

If you want a complete contrast with Caernarfon, then Penrhyn Castle, near Bangor, is the place to choose. At first glance it’s a massive, grey gloomy Norman structure. It positively glowers at you as you approach it. But relax: it’s entirely fake. Yes, there was an early tower (keep) on the site, but it was almost completely smothered by the huge Victorian ‘castle’ designed by Thomas Hopper in the 1820s and ‘30s. Both Caernarfon and Penrhyn were designed to impress; the former does so with grace and elegance, the latter with brooding menace that owes much to the then popular fashion for Gothick horror. And I don’t think it helps that the man and the family with the vast fortune that paid Hopper, acquired their wealth from slave-run sugar plantations in Jamaica. That fact alone somehow makes the building even darker.

Penrhyn Castle, Bangor. An early Victorian reconstruction.

The buildings of north Wales are very varied, which is one of the reasons they make for an excellent holiday. Sometimes an itinerary of churches alone can become rather wearisome, leading to extended lunches and sleepy afternoons. On a visit to Conwy we strayed into the town, away from the massive walls, to see the superb Elizabethan townhouse of Plas Mawr (in English: Great Hall). This is a hidden jewel. Simon Jenkins in his superb book, Wales: Churches, Houses, Castles describes it as ‘…the most splendid town mansion of the Tudor period remaining in Britain.’ Built in 1576, and enlarged shortly thereafter by a family of prosperous Welsh merchants, this wonderful house (I shall resist the temptation to describe it as a monument to mercantile munificence) was not rebuilt and enlarged in the 18th and 19th centuries – the fate of so many Tudor town and country houses in England – so its interiors, including superb plasterwork, remain remarkably intact.

The Tudor merchant’s house, Plas Mawr, Conwy.

But we did manage to visit at least one church (sadly, as happens these days, some were locked) and it was most remarkable, being essentially all of one period (Perpendicular – 15th Century), although it was actually founded very much earlier, in the 7th Century. Pilgrims would make their way from Caernarfon to Bardsey Abbey on its small island off the western tip of the Lleyn Peninsula, as part of a pilgrimage route along the north coast that became hugely popular In the later Middle Ages. The church of St. Beuno, at Clynnog Fawr (where the eponymous saint’s bones are buried) was the starting and assembly point for the pilgrimage, which still takes place from time to time to this day. But what makes this church remarkable, is its range of medieval and later church furniture including a fine screen, chests and a remarkable device for catching dogs. I doubt the RSPCA would approve of it.

And finally, those wonderful Lleyn sheep, which were all around us, although very often I could detect that many lambs had been crossed with a Charollais ram. It’s an excellent cross and produces a fine lamb with well-built hind quarters. But these sheep I photographed on the edge of marshy ground near Llangian, were all, I think, pure-bred Lleyns. And they looked in very good order indeed. Let’s hope lamb prices pick up later in the year!

July 7, 2015

Goodbye To All That

Somehow the title of Robert Graves’ 1929 autobiographical masterpiece seems strangely relevant. Does it express regret, or inevitability – or a bit of each? I suspect the latter. And that’s how I feel, too, when it comes to the demise of Time Team and the sad death of Mick Aston. In fact, the two events seem inextricably bound together in my mind, although I don’t believe they were actually connected in reality. Put another way, Mick’s demise did not signal the end of the series, because I’m convinced it was going to fold whatever the production company or we, the participants, did. I think it’s fairly plain now that Time Team was a product of a different, pre-internet, age when television was still king and when there was far more money to spend on the production of programmes. But I don’t want to sound like an old fart: I’m not suggesting that lower budgets necessarily mean poorer quality. Quite the reverse, in fact: less cash can often stimulate new ideas and fresh approaches. It’ll be interesting to see what the future holds. Personally I’m quite optimistic: if nothing else, Time Team has produced a large number of independent performers, directors and producers who now understand, or even better, are fully qualified in archaeology. These are the people who will take the story forward. And I wish them all the very best.

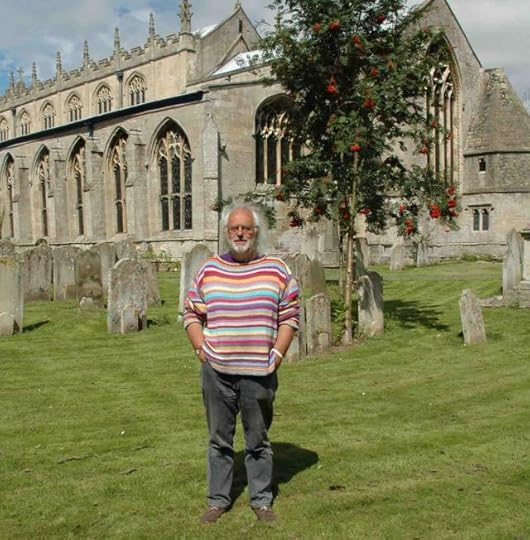

I’d known Mick for at least thirty years, but only got really friendly with him when we started making Time Teams together, from about 1995. And there’s nothing like the tension and concentration required during filming to draw people closer together. It would be an exaggeration to say it’s like being under fire, but I’m sure you know what I mean. Anyhow, I suggested the first Time Team documentary, Seahenge, and I got to know Mick very well indeed as we squatted on the leeward side of those Norfolk sand dunes, while the cameras filmed another sequence down on the windy beach. I think it was then that Mick discovered that I wasn’t just a prehistorian: that I shared with him an interest in landscape history and old buildings. Indeed, he was to give me much sound advice while I was writing two of my post-Roman books, Britain AD (2004) and Britain in the Middle Ages (2006). Over the years we would often visit churches together and in 2007 he very kindly agreed to launch the fund-raising campaign to repair the roof of our magnificent local church at Long Sutton, in Lincolnshire – which in retrospect was rather odd, as we were both convinced atheists! Mick was a modest man and he disliked being a TV celeb. My wife Maisie had agreed to take his photo, but he wouldn’t wear his trade-mark striped jumper until the very last minute, as he dreaded being recognised. So we have two pictures of him standing in front of Long Sutton Church: our ‘private’ one as a friend (in a plain top) and a ‘branded’ (stripey sweater) one for the church fund-raising campaign. I’m sorry, but we’re keeping the private one to ourselves.

I started thinking about writing The Lifers’ Club while we were filming the penultimate Time Team Series, 19, in 2011 (it was broadcast in 2012). By then, Channel 4 wanted to make some quite drastic changes to the format in a vain attempt to stop the decline in viewer numbers that was happening right across television. I don’t think the insertion of younger presenters worked, even though the two individuals themselves did very well. And I know Mick wasn’t at all happy with the changes, either. He agreed to be archaeological director for six of the twelve episodes, while I did most of the others, but we stayed in close touch. I always regarded Time Team as Mick’s baby and I wasn’t about to do anything he wasn’t happy with. I also think it helped that we had different fields of expertise: I was Pre-Roman, he was Post. In the early series, Time Teams rarely ventured into prehistory, but when they did, it was often with my help. But throughout, Mick and I continued to share a common interest in landscape history, which often came together when we made films about the early industrial era, the building of the railways, and suchlike.

My fondest memories of Mick are from Series 18, the last of the ‘normal’ Time Teams. The episode concerned was filmed on the edge of Dartmoor, at Tottiford, in Devon. We had rooms next door to each other in the hotel and shared a large balcony. I didn’t know it when we began filming, but this was the 200th Time Team, which was why Mick was the Archaeological Director and I was the on-screen expert. I need hardly add that we had discussed the dig strategy well in advance and were in complete agreement on what had to be done. The site chosen was remarkable: a nearly-dry reservoir, which held a miniature prehistoric ‘ritual landscape’, complete with a double stone row and a stone circle. A low mound revealed an intact Mesolithic settlement, which may well have been the original focus of the site – some three or four thousand years previously. Mick had a very expressive face which was rarely still. In this picture, taken beside a collapsed stone of the circle, he is having a vigorous discussion with me about whether that collapse was deliberate (as I thought) or accidental (as he maintained). You can almost hear him shouting at me in frustration!

During the afternoon tea-break on Day 3 (I think) Mick cut the special cake and we all had a slice. Unfortunately my camera lens got spattered with mud just before the ceremonial slicing, so I couldn’t capture the moment. But the cake was delicious.

I first had the idea of setting my second Alan Cadbury mystery on a television shoot shortly after it was announced that Time Team would fold. Maybe I realised that it was the end of an era, but I also knew it was something I had to do. There was so much that was good and honest about Time Team. Of course it had its short-comings – nothing is ever perfect – but it was driven by a sense of wonder at what people had achieved in the past. It was also about hope for the future, about balance, perspective and humour in a world that seems increasingly focussed on the ephemeral and the extreme. And that’s why I had to dedicate The Way, The Truth and The Dead to Mick’s memory. I think it would have made him smile and I hope it will provide a little background to the better-known legacy, of his many books and television films. The dedication of the second Alan Cadbury mystery includes my favourite picture of Mick, which I took on our balcony at the Tottiford hotel. You’ll never guess, but five minutes later we adjourned to the bar. Ah, happy days!

Both The Lifers’ Club and its follow-up, The Way. The Truth and The Dead are published by Unbound, Britains first (and best!) crowd-funding publisher. The Lifers’ Club is already available (in print and ebook), but The Way, The Truth and The Dead is still open to subscribers. Everyone who subscribes has their name included in a list at the back of the book and in all its future editions. So if you’d like to join dozens of Time Team members and production staff, not to mention a crowd of famous archaeologists and TV personalities, click on this link. Have a credit/debit card handy and it won’t cost you a fortune (£10 for the ebook and £24 for the hardback incl. p&p). And one other favour: can I ask you to forward this to any friend who might enjoy it? We’re SO nearly published (over 60% and rising). Thanks a million!

June 19, 2015

Beds as Pictures

Before you jump to the wrong conclusion: no, this won’t be a blog post about Tracy Emin’s early work. In fact it won’t be about any of her work, because the beds are garden beds, but this time I want to think about them as elements of composition. And if that sounds a little bit pompous and posey, I’m sorry, but gardening is ultimately about creating impressions and sensations – and in that respect it’s an Art, with a capital ‘A’. Indeed I’d go further: traditionally artists have worked in two, or if they’re sculptors, three dimensions. But gardeners have also to deal with the added complexities of scent and weather. Time, too, is another dimension that often gets overlooked: part of the genius of men like Capability Brown and Humphrey Repton was the way they could foresee the way their created landscapes would appear in a hundred years’ time. I’ll never forget seeing an avenue of saplings – they were limes I think – that had been planted at Wimpole Hall, outside Cambridge, to replace elms killed by Dutch Elm Disease. They looked puny and frankly ridiculous, as those trademark clumps of trees must once have done, that today grace the middle distance, often beyond a picturesque lake, complete with bridge, in so many Brown and Repton country house parks. It’s no wonder that Repton gave clients his famous Red Books. I think I’d have needed something similar if I’d just spent a fortune on what must have looked like a devastated scene.

Now much as we’d like to work on a big scale, ours is a much smaller problem, albeit massive by modern urban standards: our wood, orchard, hay meadow and garden together probably occupy about 15 acres, at the very most. But now I want to examine the basic unit for most practical gardeners: the flower bed. Some are formal, others informal or informal-verging-on-the-chaotic. Some include ground cover; some have clear ‘islands’ of particular plants or flowers, while in others the plants blend or even fight among themselves. And then of course there are the trees and shrubs that rise above or beyond the beds. These are essential, as they give the bed its distinctive light, shade and shelter. They also determine the sort of plants that can be used around them: the shed needles (leaves) of pines, for example, tend to acidify the soil. And that’s another reason why we tend not to be very tidy gardeners: we don’t religiously sweep everything up, because sometimes it’s good to have acid patches if you want to grow lime-hating bulbs, for example. Tidy gardens are also very unfriendly to wildlife, so we tend not to cut our border perennials back in the autumn. We’d rather the birds had their seed-heads to keep them going over winter – even if that does mean a few more seedlings to weed-out the following spring. Remember: a ‘weed’ is just a plant in the wrong place.

So for this blog post, I took my camera around the garden with bed composition in mind – and came up with a few thoughts.

I suppose the most rigidly formal beds in our garden are in my vegetable garden (I say ‘my’ because I mostly work there; Maisie’s bed is the long border, where she can usually be found bent double over a geranium or three). I took this photo shortly after hoeing-off the late spring weeds. Note the high hornbeam hedge, which protects the garden against north-easterly winds. As this garden produces food, I don’t use weed-killers, or indeed slug pellets which kill the hedgehogs that feed on the slugs. There’s not much to say about it, other than the onions are doing well. I’m aware the micro-mesh ‘fleece’ isn’t very slightly, but then it prevents cabbage white butterflies from laying their eggs on next season’s brassicas. So that’s too bad. And anyhow, I think there’s a big difference between business-like and ugly. Some contrived mixed flower and veg gardens are neither one thing nor the other. I want my veg garden to produce good, tasty food. And lots of it. So yes, it is formal and quite disciplined, but that makes it easier for me to water, feed, weed and harvest.

This is a view along one of the paths in our rose garden. Now our rose garden is what you might call a ‘mixed’ rose garden. Yes, there are roses, but we both firmly believe that roses look rather sterile on their own, so we like to plant around them. They also don’t flower all year. So in this view the roses have yet to come into flower and the stage is taken-over by the wet-loving Iris pallida Dalmatica. The small splash of red at the end of the walk are oriental poppies. The tree on the left is an unusual cut-leaved form of the native British alder, Alnus glutinosa (which we bought at the superb Scottish botanic garden at Dawyck – a name that finds its way into my crime thriller, The Lifers’ Club). But note the space between the plants. Here I think the bare soil, although a pain to keep weed-free, is making a statement. It enhances the irises and adds to the formality of the set-piece.

This path, which bounds the rose garden to the north-east, continues the somewhat formal theme of the first picture, but we’re now moving into less formal territory. Yes, the beds and path have straight, cut edges, but the planting is becoming less regimented: seedlings, for example, are not always weeded-out. Here the tree-cover is provided by the Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) and in the distance is a hornbeam hedge (our land is too wet for beech). The areas of bare earth between plants are smaller, and most will get grown-over as the summer advances. This bed features narcissi, followed by hemerocallis, and (for later in the year) fuchsias. The white flowered shrub is Viburnum opulus compactum. And that’s another thing about effective bed-management: this should change with the seasons. I always get rather fed-up when I visit great country gardens and discover that a particular garden is, say, for late springtime hyacinths – only. For my money, that’s a cop-out.

Not all beds can be carefully structured. Sometimes the location, in this case it’s very damp and shady, is challenging; in other cases a bed might still be in its infancy. In this particular instance, both apply. The bed is close to our small summer house, the Tea Shed (which I described in an earlier blog post), which sits on the edge of the wood, not far from the meadow. As a result, weed seeds blow in constantly. So we needed a rapidly spreading ground-cover. We happened to have a few plants of the pinkish-red flowering strawberry, Fragaria chiloensis, whose small fruits are rare, but not unpleasant if dropped into a glass of white wine. It flowers from spring right through to later autumn, so is excellent value, but it hadn’t spread much where we had it, which was too dry. So I took a chance and moved half a dozen plants to the new bed. That was in the autumn of 2012. By the same time next year the bed was a quarter covered. By the end of 2014 only ten percent remained bare earth. And as you can see, now we have total cover – which is convenient if we happen to be enjoying a glass of something cool and refreshing in the Tea Shed.

But there is a time and a place for contrast. We both dislike over-controlled gardens – you know, the sort of places where they knot the daffodil leaves tidily, as soon as they’ve finished flowering. Maisie has a wonderful eye for colour and we’re constantly looking for new effects. Self-seeded plants can form wonderfully unexpected associations – again something one rather misses in so many of the large country house gardens run by the great national bodies (I shall mention no names), where everything has to be planned. And of course spontaneity – and yes, horticultural humour – suffer. Anyhow, this picture shows the path to our back door. It’s a scene of barely controlled anarchy. An overgrown box hedge is being clipped by our neighbour into a Loch Ness monster, with ears. The second asparagus bed forms a backdrop to the planting, which at this time of year consists of oriental and opium poppies, plus various geraniums. I’m delighted to say that while horticultural snobs might turn up their noses, this bed is very popular with drivers delivering things to the farm. I love it, too, because no two years are ever the same.

Francis Pryor's Blog

- Francis Pryor's profile

- 141 followers