Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 801

September 21, 2018

Innovation Should Be a Top Priority for Boards. So Why Isn’t It?

Jason Jaroslav Cook Creative/Getty Images

Jason Jaroslav Cook Creative/Getty ImagesCorporate directors and executives alike recognize that today’s pace of change continues to accelerate and that firms need to innovate to stay ahead. But are boards doing enough to support innovation, as they should? We conducted a survey of over 5,000 board members from around the world to find out.

We found that, overall, innovation does not rank as a top strategic challenge for the majority of boards. Although directors in certain industries are more aware of the threat of disruption, the widespread lack of board-level engagement in innovation processes could be a major blind spot and a potential liability.

Setting Priorities

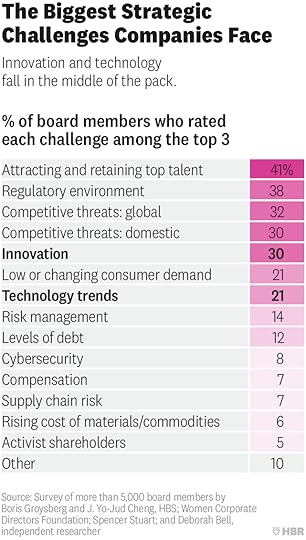

We found that concerns about innovation fall behind other issues for most directors. Fewer than one-third (30%) of respondents to our survey see innovation as one of the top three challenges their company faces in achieving its strategic objectives, and just 21% think that technology trends are a major strategic challenge. Innovation ranks fifth, after more-conventional concerns such as attracting and retaining top talent and the regulatory environment.

Boards’ abilities to foster innovation clearly fall short when compared with their other activities. When we asked directors about the effectiveness of their board’s processes for supporting innovation, 42% rated their processes as above average or excellent. In contrast, 70% of respondents think their boards have effective processes for staying current on the company; 69% for compliance; 66% for financial planning; and 55% for risk management — although we should note that managing risks is a crucial consideration when pursuing innovation. Still, it’s telling that board members rate their boards better on risk management than on innovation.

When we examined responses by industry, we found that directors in the health care and IT and telecom industries were most likely to consider innovation a top strategic challenge for their firms. These firms also had higher-rated processes for innovation. This isn’t all that surprising given the level of innovation activity in these sectors, but directors operating in similarly disrupted sectors should take note. Only 13% of directors in the energy and utilities industry consider innovation to be a major strategic challenge, but the swift growth of renewable energy companies and such developments as the use of drones for monitoring oil and gas production suggest that no industry is impervious to the forces of innovation.

We also found that a focus on innovation tends to go hand in hand with longer-term time horizons. Companies that are organized around creating and enhancing value over the long term were more likely to have boards that prioritize innovation, as compared with companies that are primarily focused on achieving short-term results. Laying the foundation for innovation requires a forward-looking mindset throughout the firm and the board.

The effectiveness of board processes for supporting innovation is also positively correlated with overall board performance. In other words, the boards with strong innovation processes tend to be the ones that are performing well on all fronts.

Director Recruitment and Skills

In light of boards’ lackluster performance on innovation, are they proactively taking steps to address their weaknesses? Recruiting directors with technological expertise is one avenue through which boards can boost their innovative capabilities. When we asked directors which three areas of expertise they prioritized when filling their most recent open board seat, just 13% highlighted tech expertise. Instead, boards typically looked for expertise in their firms’ industry (51%), strategy (34%), and financials (30%).

Again, we found differences among industries. Just over one-fifth (22%) of boards operating in the IT and telecom industry sought tech expertise when filling their most recent board seat, higher than in any other industry. We also observed that boards of larger companies were more likely to seek new directors with technological expertise. When we drilled down, we found that boards with more members and boards that were more effective overall were also more likely to prioritize tech expertise, suggesting that boards might need to meet a certain size and performance threshold before they start branching into skills such as technology. In the words of one director, there is an “imbalance between the need to focus on governance and compliance, while the importance of innovation and disruptive influences are noted but less focused on.”

When we asked directors what they found most challenging in their role as a director, one-third (33%) reported that they struggled with keeping on top of new technologies. This proportion was similar for men (34%) and women (31%), but was much higher for older directors (39%) than for younger directors (27%). Fostering diversity in demographics is one pathway boards can use to ensure that a wide range of viewpoints and areas of expertise is represented.

How Boards Can Foster Innovation

To address the knowledge gaps and get up to speed on new initiatives within the firm, directors suggest organizing site visits and tours, participating in innovation sessions and workshops within the firm, and “doing their homework” on industry trends.

Directors should also take stock of how time is spent at board meetings and reallocate discussion time as needed. As one director noted, “We spend a lot of time on operational strategy — growth, acquisitions, etc. — [and] not much on risk, people, innovation.” Periodic reviews of board agendas can help to carve out and protect time for discussions around innovation.

Boards also need to have honest and thorough discussions about the board’s weaknesses and needs when formulating criteria for new directors. Some might even want to consider increasing their membership to ensure that they have the skills they need as a team and that they represent a wide enough array of perspectives.

About the Research

This survey was conducted through a partnership between Boris Groysberg and Yo-Jud Cheng from Harvard Business School; WomenCorporateDirectors Foundation, led by Susan Stautberg; Spencer Stuart, led by Julie Hembrock Daum; and independent researcher Deborah Bell.

Over 5,000 board members of companies headquartered in more than 60 countries responded to the survey between October 2015 and June 2016. Most responses (80%) were received between October and December 2015. Between January and June 2016, we worked with Harvard Business School’s Global Research Centers to increase the response rate outside of the United States. Additional responses from this second survey wave were predominantly concentrated in the Middle East, Asia, and Western Europe.

The industry breakdowns were determined using eight major sectors (similar to those in the Global Industry Classification Standard system): Consumer Discretionary (e.g., apparel, automobiles, retailing, media, hotels, restaurants & leisure); Consumer Staples (e.g., food, beverage & tobacco, household and personal products); Energy & Utilities (e.g., oil, gas & consumable fuels, electric, gas and water utilities); Financial & Professional services (e.g., banking & financial services, insurance, real estate); Healthcare (e.g., pharmaceuticals, biotechnology & life sciences, health care equipment and services); Industrials (e.g., aerospace & defense, industrial conglomerates, textiles); IT & Telecommunications (e.g., internet software & services, semiconductors, wireless telecommunication services); and Materials (e.g., chemicals, metals & mining, paper & forest products).

Breakdowns on company size were based on annual revenue quartiles. Breakdowns on board size were based on the following four groups: 6 or fewer directors; 7-8 directors; 9-10 directors; and 11 or more directors. Breakdowns on overall board rating were based on two groups: boards rated as a 1 or 2 (poor or below average) out of 5; and boards rated as a 4 or 5 (above average or excellent) out of 5.

To better understand the competitive landscape, directors suggested engaging with management. They should ask such questions as, “In what areas and where will technology innovation impact our business?”; “How are you incorporating the latest customer and technology trends in your innovation strategy?”; and “How can this company devote adequate resources to innovation in its product offerings in light of debt and capital requirements?”

Finally, boards should always be checking that they have the right CEO in charge. A CEO who focuses on short-term results at the expense of creating long-term value might not be making the right decisions and investments to promote vital innovation within the firm.

People Who Graduate During Recessions Earn Less Money — but They’re Happier

adamkaz/Getty Images

adamkaz/Getty ImagesWhen the graduating classes of 2009, 2010, and 2011 hit the job market, their employment prospects were depressingly bleak. Unemployment rates were at historic highs and job openings were scarce. Nine months after graduation, only 56% of the class of 2010 had found a job. Many of those who did find work held jobs that were temporary, lacked benefits, or did not require a college degree.

These early career experiences appear to have lasting negative consequences for later career success. For instance, people who graduate in recessions earn less money than their counterparts who graduated in more-favorable economic times, even decades later. They also tend to work for smaller, less-prestigious, and lower-paying firms. Similar patterns emerge among people who reach the pinnacle of corporate life: CEOs. Recession graduates who become CEOs often run smaller, less-prestigious companies than their counterparts who started in more-prosperous economic times.

While there is little doubt that recessions have lasting negative effects on salaries and occupational prestige, they appear to have some surprisingly positive implications for other aspects of people’s working lives.

For one, people who enter the workforce in a recession tend to be happier with their jobs, compared with people who graduate in better economic times. For instance, in one paper I examined the job attitudes of 1,638 people over a 15-year period. Even though they earned less money than people who started their careers in better economic times, recession graduates were significantly happier with their jobs both early in their careers and years later. These effects could not be explained by different industry or occupational choices. Instead, recession graduates tended to think about their jobs in more-positive and ultimately satisfying ways. Rather than ruminating over unfollowed paths or wondering what might have been, they focused on what was good about their jobs and were more grateful for the jobs they held. People who began their careers in prosperous times, on the other hand, were more likely to be plagued by regret, second-guessing, and what-ifs.

Entering the workforce in a recession appears to affect not only how people think about their jobs but also how they think about themselves. One metric of self-focus is narcissism: the belief that one is special, unique, and entitled to good outcomes. This way of being can be costly at work. Narcissists tend focus on their own interests even if doing so is harmful to others. They are also particularly likely to become angry or aggressive and to steal from their employers or shareholders.

One reason that recession graduates might be less likely to develop a grandiose sense of self is that narcissism seems to be tempered by adversity and setbacks. People who begin their careers during economic downturns often have a more difficult time finding work and establishing their careers. Many are forced to move back home, work in jobs that do not require a college degree, or cobble together part-time gigs. While these challenges can make it difficult to establish independence and build a career, they also appear to hamper the development of an overinflated ego.

I tested whether graduating in a recession did in fact temper narcissism, using data from a representative sample of over 30,000 Americans. I found that people who entered adulthood during worse economic times were less narcissistic than those who came of age in more-prosperous times. Similar effects even emerged among CEOs. Company leaders who began their careers in challenging economic times were less narcissistic than CEOs who began their careers in more-prosperous times.

If entering the workforce during a recession affects people’s sense of grandiosity and entitlement, could it also affect their willingness to engage in unethical business practices? Some evidence suggests it could. Past work has shown that narcissists are more likely to behave unethically, sabotage their coworkers, and be convicted of white-collar crime. Given that recession graduates are less likely to be narcissistic, could they also be less likely to be traverse moral and ethical lines? Consistent with this idea, my colleague Aharon Mohliver and I found that CEOs who first began their careers in worse economic times were less likely to backdate their stock options, an unethical, illegal, and common practice in the late 1990s and early 2000s. So not only were recession graduates less likely to regard themselves as supremely important and deserving of outsize attention and praise, but they were also less likely to engage in behavior that enriched themselves at the expense of their organizations.

Many people who started their careers during the Great Recession still bear the scars of entering the workforce during that tumultuous and uncertain time. They may have gaps in their résumés and fewer zeros in their salaries. But these tough experiences may have helped shape them into happier, less-self-absorbed, and more-ethical employees.

September 20, 2018

Resignations

Are you looking to quit your job? In this episode of HBR’s advice podcast, Dear HBR:, cohosts Alison Beard and Dan McGinn answer your questions with the help of David Burkus, a management professor at Oral Roberts University. They talk through what to do when you want to call out a toxic employee in your resignation letter, reject a counteroffer, or resign without burning bridges.

Listen to more episodes and find out how to subscribe on the Dear HBR: page. Email your questions about your workplace dilemmas to Dan and Alison at dearhbr@hbr.org.

From Alison and Dan’s reading list for this episode:

HBR: What to Do After You Tell Your Boss You’re Leaving by Carolyn O’Hara — “Don’t sully your hard-won reputation by slacking off in your final few weeks. Go out on a high note by making sure that files and clients are transferred in a timely and organized fashion and that deadlines won’t be overlooked in your absence. And take the time to express gratitude for the opportunities you’ve had there. You may see former managers and colleagues again at other companies, especially if you remain in the same industry.”

HBR: 7 Ways People Quit Their Jobs by Anthony C. Klotz and Mark C. Bolino — “Not surprisingly, we also found that while most voluntary turnover tends to be unpleasant for managers, they are particularly frustrated and angry when employees leave in a perfunctory, avoidant, or bridge burning manner. So employees who want to leave on good terms should steer clear of these strategies.”

HBR: Setting the Record Straight: Using an Outside Offer to Get a Raise by Amy Gallo — “You also have to think about possibly damaging your relationship with people at the organization from which you got the offer if they assumed you planned on leaving your job and now you’re turning them down to stay. The hiring manager and others there likely spent time and energy interviewing you, assessing whether you’re a fit, and internally negotiating the specifics of your offer. If it’s a place you’d like to work in the future, you have to consider whether using their offer to get more from your current employee will hurt your chances to apply again later on.”

HBR: Is It Time to Quit Your Job? by Amy Gallo — “Before making a final decision, make sure you’ve assessed the downsides. Even if you’re certain you’re in the wrong job, there are risks to leaving — you may damage existing relationships, lose needed income, or blemish your resume.”

How to Help Your Team Manage Grunt Work

Brett Hemmings/Getty Images

Brett Hemmings/Getty ImagesIn So I Married an Axe Murderer, a wacky 1990’s parody, a police officer named Tony confides to his captain, “I’m having doubts about being a cop. You know, it’s not like how it is on TV. All I do all day is fill out forms and paperwork.”

Tony thought his job would be more thrilling than it has turned out to be. Tony is not alone. Every job contains some unglamorous grunt work.

I am a great proponent of the joys of work. But not every part of every job is a joy. While we all want to find a level of meaning and purpose in our work, often, some fraction of our time has to be spent doing tasks that have no intrinsic meaning and serve no deeper purpose than helping to keep the workplace trains running.

This can be especially tough for early-career professionals to accept, especially those in entry-level positions. College life is often flexible, challenging, and engaging, and after four years of that it can be hard to sit still in an office for hours at time, doing administrative tasks, without thinking, I earned a college degree for this? But it’s not just recent graduates who struggle with grunt work. Anyone of any age can think their role should only entail tasks that are exciting or fulfilling and that the drudge work is beneath them and should be someone else’s problem.

You and Your Team Series

Retention

How to Lose Your Best Employees

Whitney Johnson

To Retain New Hires, Make Sure You Meet with Them in Their First Week

Dawn Klinghoffer et al.

Why Great Employees Leave “Great Cultures”

Melissa Daimler

Whatever its source, entitlement is a career killer, a noose with which employees of any generation can — and do — hang themselves. If someone you manage is complaining to you about the amount of grunt work they have, you need to figure out a way to help them get over their frustration and see that everyone on the team has grunt work they have to do, and also learn to manage their time so that they don’t short-change higher-value activities. (For the purposes of this article, I’m assuming that as a manager, you’ve assigned these tasks fairly, and the employee in question isn’t actually burdened with too many non-promotable tasks.)

Here are a few techniques I suggest to help them shrink the amount of time they spend on grunt work, while still getting it done:

Impose constraints: If an employee is filling her days with low-level tasks that could be completed in much less time, impose a time constraint. Morning email needs to be answered by 10am. Calls need to be returned within one hour. The previous week’s data needs to be compiled and reported by Monday at 4pm.

Time management is a skill that many need help to learn, and as a manager, you may need to be the teacher. Expect some pushback — an employee is likely to say that they can’t complete X task in half the time. But push them to at least try. They may surprise themselves. And an often overlooked upside is that a ho-hum task can become a more engaging challenge when a time constraint is imposed.

Dangle the carrot: What is the more interesting work that the employee would like to be doing? What is your vision of what the employee could be doing for the firm? Have the conversation. Help the employee visualize the new opportunities that could complement their ordinary tasks. Perhaps pair the employee with a more mature worker who can mentor them in time management and also inspire with a glimpse of the different types of work the firm engages in. Adding more-appealing work to their portfolio will compel them to shrink the amount of time they spend on lower-value work.

Shake the stick: A dangled carrot is positive motivation, but consequences can be effective as well. Employees who spend hours on tasks that really are not that important are not spending their time on the right things. Establish goals for an employee’s most value-added work, and consequences if they don’t meet those goals.

Shrinking the amount of time your employee is spending on the dull tasks should help mitigate their frustration at having to do them at all. If it doesn’t, you may need to have a larger conversation about their career goals and whether they can meet them in their current role, or even at your firm.

Remind them that positivity itself is promotable. When you hire or promote someone, it’s because of the tasks you think they can do for your organization. But you also want to hire people who have a good attitude — who will pitch in and do what needs to be done. Sometimes taking care of the grunt work is just about showing that you can be a team player with a great attitude. If a manager can trust you with the boring stuff, then you can definitely be trusted with the exciting stuff. Remind your employee that sometimes, it’s not about what you’re doing but how you go about doing it.

Model the behavior. So much work is invisible. We know what we’re spending time on, but does anyone else? When an employee complains about the scut work they have to do, it’s probably because they don’t see how much scut work everyone — including their boss — has to do. Make the work on your team more transparent. Talk to the employee about how everyone — even you — has to spend a certain percentage of their time on these kinds of tasks. Make sure your team sees you occasionally taking on these tasks.

I love the story told about Sam Pitroda, then the head of C-DOT, India’s telecommunications enterprise. C-DOT had two floors of a five-star hotel as their workspace. A repairman had been called to fix a broken doorknob on the boardroom. Repair completed, he packed up his tools and prepared to leave — both the boardroom and the mess he’d made while making the repair. Pitroda asked for a broom, invited the man to sit and proceeded to clean up the mess while he watched. A great lesson which should be taught in more workplaces — the task is not beneath the CEO; it isn’t beneath anyone else either.

Perhaps you recognize that you’re not the manager of an employee in this scenario; you are the employee. These techniques will work for you as well. Outline your own objectives and practice the discipline to achieve them. Establish time limits for accomplishing unpleasant tasks, a schedule for completing less-than-thrilling projects and reward yourself for achieving these goals. Have a negative consequence in mind if you don’t make the effort and impose the consequence if you should. Also recognize that this is an opportunity to shine. Inexperience has the advantage of fresh eyes. If some of your work is too time-consuming, try to innovate a more efficient process that hasn’t yet occurred to your boss or coworkers. When it comes to battling entitlement, good self-management is the most powerful weapon of all.

Reality TV Doesn’t Have To Be Dumb - SPONSOR CONTENT FROM QATAR FOUNDATION

Stars of Science, a reality TV “edutainment” competition for the Arab world, is set to celebrate its 10th anniversary, owing to its success as a show that rewards innovation above all else.

Within less than 20 years, the phenomenon commonly referred to as “reality TV” has fundamentally altered television viewing habits the world over. Though the genre of unscripted entertainment is as old as television itself, it was not until the early 2000s that viewers became enraptured by the sight of survivalists competing on desert islands, budding pop stars taking the stage, and business hopefuls getting fired by a future US president.

In the Arab world, reality TV is a similar cultural phenomenon, with nation-specific and regional competitions seeking to discover singing and dancing talents. But amid the array of options that offer fame as a reward for innate talent, there is a rare exception: Stars of Science, an initiative of Qatar Foundation (QF) telecast on various MENA-region TV channels annually.

The show, which employs a flagship “edutainment reality” TV format, follows the journey of nine young and aspiring innovators from around the region as they attempt to develop and create their inventions at the laboratories of Qatar Science & Technology Park, a member of QF.

“I’ve always been on the lookout for platforms that reach massive amounts of people all over the world and that inspire them to reach their potential,” says Dr. Khalid Al Ali, founder and executive chairman of Grupo Senseta and a member of the three-person jury on the show.

“We have contestants from all over the Arab world, including war-torn countries. For those who are finding it difficult to turn their dream into a reality, we offer them a way.”

At the end of a grueling 10-week season, the final four contestants compete for a share of US$600,000 in seed funding, with the winner determined by a panel of expert judges as well as viewers voting online.

“Think of us as Sherpas guiding a person who is climbing their own Everest,” says Dr. Al Ali of his and the other judges’ role. “Those who are worthy of reaching the peak usually make it to the top, and those who don’t climb back down and try again.”

“In my time on Stars of Science, I’ve observed life-changing stories. The show itself is an innovation, and it’s a self-generating resource. There’s nothing else like it out there.”

Transcending Divides

Though Stars of Science has been on air for nearly a decade, the show had to confront a new challenge last year in the form of regional geopolitics.

Following a decision made by certain Arab countries in June 2017 to cut off diplomatic relations with Qatar, the season finale of the Doha-based show was held outside the country for the first time. It was instead filmed in the Sultanate of Oman, as part of a collaboration the show had announced with the Oman Technology Fund.

That season saw Fouad Maksoud crowned the winner for his “Nano-shielding Textile Machine” innovation that uses nanotechnology to apply petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals to ordinary textiles for various purposes, such as making clothing waterproof or allowing the integration of healing medicine with apparel. As Maksoud recalls, the political tensions did not affect the participants on the show.

“All four of us in the final were in Oman to compete scientifically, for the good of humanity. We each had an innovation that could serve a large group of people,” says Maksoud. “Nobody was thinking, ‘This person is my enemy because their country is boycotting mine.’ It was completely the opposite.”

Inspiring Others

Maksoud’s words illustrate the sense of purpose Stars of Science has instilled among its alumni. They believe that innovation is something that should be nurtured and shared, and consequently the success of each innovator is considered a gift to all, not a prize achieved by a single entertainer.

“Stars of Science is doing a great job in providing something that is not senseless entertainment. It’s value-driven, wholesome, and builds toward an inspiring future,” says Omar Hamid, co-founder of LaunchGood, a crowdfunding platform focused on the Muslim community worldwide.

Hamid was the season seven runner-up of Stars of Science, with his in-development “Sanda” prayer chair that supports worshippers who need physical assistance while praying in a mosque. He says, “I consider Stars of Science to be a glimmer of hope in a region where that is often lacking. Too often in the Arab world, people idealize a vision of the past.”

“The problem with this is that if you only look backward, it becomes difficult to envision how the region can become in the future. I think Stars of Science helps to change that mindset, shifting the focus away from nostalgia and toward an inspired future.”

To learn more about other initiatives of Qatar Foundation, visit www.qf.org.qa.

Research: 83% of Executives Say They Encourage Curiosity. Just 52% of Employees Agree.

Danas Jurgelevicius/Getty Images

Danas Jurgelevicius/Getty ImagesCuriosity is experiencing a “Gold Rush” moment. Books, university classes, and research are popularizing the power of curiosity.

Not surprisingly, organizations are increasingly, explicitly looking for curious employees. Consider these job descriptions pulled from several job listing websites:

“If you have a passion and curiosity for what is possible and enjoy people, we invite you to join us on this mission” (posting for a retail sales position);

“We are counting on you to bring a genuine curiosity about how consumers search for information” (posting for a data analyst role);

“Because our world is continuously evolving, you’ll need to possess curiosity and a love of learning” (posting for a digital content writer role).

Given the importance of curiosity for organizations, our research sheds light on an astounding conundrum that most organizations face. Leaders assume—mistakenly for the most part—that their employees feel empowered to be curious. They see few barriers themselves to asking questions and assume the same is true for their employees. But employees describe a very different reality.

We surveyed more than 23,000 people, including 16,000 employees and over 1,500 C-suite leaders, to understand how they view the role of curiosity at their organizations, across industries and at various levels of leadership.

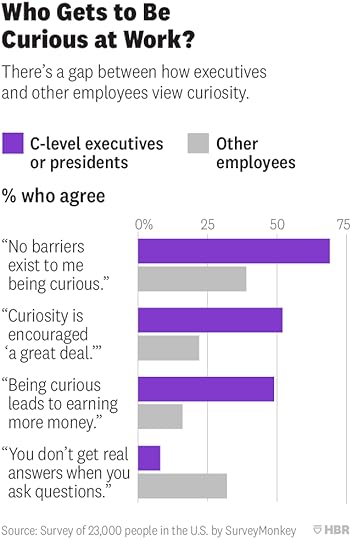

83% of C-level or president-level executives say curiosity is encouraged “a great deal” or “a good amount” at their company. Just 52% of individual contributors say the same. This gap seems to be driven in part by perceptions of the value of curiosity.

While about half (49%) of the C-level believes curiosity is rewarded by salary growth, only 16% of individual contributors agree. A staggering 81% of individual contributors are convinced curiosity makes no material difference in their compensation.

This is an enormous problem for businesses because if lower-level contributors don’t see the value of curiosity then they are less likely to act as a source of new information for the organization.

So, if curiosity is so coveted and valuable, what’s happening to individual contributors who feel their curiosity is stifled at work? What’s an employer to do? Our research shows there is hope for curiosity. In working with organizations, we’ve discovered one lynchpin for leveraging curiosity—identity.

Identity can influence curiosity in two ways:

First, an individual’s identity is not monolithic, instead it is a collection of varied interests. For example, a computer programmer may also identify as an“outdoor enthusiast,” “parent,” or “community volunteer” outside of work. Each interest carries with it a different willingness to explore, so the same person will be in a more or less of a curious mindset depending on which interest they are engaging. The “computer programmer” might have a single job to execute with little room to ask questions and be curious. In contrast, the same person’s “outdoor enthusiast” identity might have a rhythm of exploration that includes hikes to new destinations. Leaders can leverage this insight by encouraging individuals to bring their interests with them to work. After all, the word curiosity derives from the Latin “to care;” if people don’t care, they don’t ask.

Second, identity can authorize curiosity. Nobel laureates’ biographies often include moments when a teacher, a parent, or a respected leader authorized their curiosity. For example, Mae Jemison, the first African American female astronaut, noted that she was constantly curious as a child. She observed that her curiosity didn’t “lose [its] energy” in part because it was reinforced by a summer internship at Bell Laboratories: “You get this reinforcement, and that’s the kind of role that companies and corporations can play,” she said. Once curiosity becomes a part of an individual’s identity then they feel authorized to ask questions that might upset the status quo.

Our data strongly suggest that curiosity helps employees engage more deeply in their work, generate new ideas, and share those ideas with others. When feeling curious at work, 73% of individual contributors report “sharing ideas more” and “generating new ideas for their organizations.”

Successful organizations are rooted in curiosity. To generate new ideas and add value to their organizations, employees at all levels need an environment where they can be curious, seek and absorb new information, and make new connections. A disconnect between leaders’ and employees’ assumptions about the value of curiosity within an organization prevents new information from flowing into the organization. Unless leaders can see the barriers to curiosity throughout their organizations and create systems for it to flourish, they will remain in a prison of their own construction: believing themselves free to be curious and therefore believing everyone else is equally curious and unimpeded.

4 Ways Busy People Sabotage Themselves

ImageGap/Getty Images

ImageGap/Getty ImagesYou’ve left an important task undone for weeks. It’s hanging over you, causing daily anxiety. And yet instead of actually doing it, you do a hundred other tasks instead.

Or you’ve been feeling guilty about not replying to an email, even though replying would only take 10 minutes.

Or maybe the last time you needed stamps, you went to the post office to buy a single stamp because you couldn’t find the 100-pack you purchased a few months ago. You know it’s around… somewhere. But you just don’t have the time to clean your desk to find it.

These self-sabotaging patterns maintain a cycle of always having too much to do (or at least feeling like that’s the case). If you’re chronically tapped out of the immense amount of mental energy required for planning, decision making, and coping, it’s easy to get lured into these traps. Let’s unpack the problems in more detail and discuss solutions.

1. You keep ploughing away without stepping back and prioritizing.

When we’re busy and stressed, we often default to working on whatever has the most imminent deadline, even if it’s not particularly important. Stress causes our focus to narrow to the point where we’re just keeping going, like a hamster on a wheel. We respond to emails and go through the motions of getting things done, without actually stepping back and considering what’s most important to work on. You might find yourself spending several hours on a task that wasn’t that important to begin with, even though you have a mountain of other things to be doing.

The solution is to step back and work on tasks that are important but not urgent. Use the “pay yourself first” principle to do items that are on your priority list first, before you jump to responding to other people’s needs. You might not be able to follow this principle every day, but aim to follow it for several days of the week.

2. You completely overlook easy solutions for getting things done.

When we’re stressed, we don’t think of easy solutions that are staring us in the face. Again, this happens because we’re in tunnel vision mode, doing what we usually do and not thinking flexibly. Especially if you’re a perfectionist, when you’re overloaded it’s likely that you’ll find yourself overcomplicating solutions to problems. For example, lots of busy people don’t keep enough food in the house. This leads to a cycle of stopping in at the grocery store on an almost daily basis to pick up one or two things, or a restaurant habit that ends up being expensive, time consuming, fattening, or all of the above. The solution seems horribly complicated: hours of meal planning, shopping, and cooking.

To get out of the trap of overlooking easy solutions, take a step back and question your assumptions. If you tend to think in extremes, is there an option between the two extremes you could consider? (To solve my no-food conundrum, I bought a $150 freezer and now keep at least a dozen or so healthyish frozen meals in there, as well as frozen bread and other staples. I’m not Martha Stewart, but neither am I grabbing takeout for every meal.)

On a broader level, breaks in which you allow your mind to wander are the main solution to the problem of tunnel vision. Even short breaks can allow you to break out of too narrow thinking. Sometimes, a bathroom break can be enough. Try anything that allows you to get up out of your seat and walk around. This can be a reason not to outsource some errands. They give an opportunity to allow your mind to wander while you’re physically on the move, an ideal background for producing insights and epiphanies.

3. You “kick the can down the road” instead of creating better systems for solving recurring problems.

When our mental energy is tapped out, we’ll tend to keep doing something ourselves that we could delegate or outsource, because we don’t have the upfront cognitive oomph we need to engage a helper and set up a system. For example, say you could really benefit from some help cleaning your house, but finding someone trustworthy, agreeing on a schedule, and training them on how you like things done feels more taxing than you can deal with right now (or ever). And so you put it off, week after week, doing the work yourself — even though even reallocating the time spent on one cleaning session would realistically be enough to hire someone else to do it.

Remedies for recurring problems are often simple if you can step back enough to get perspective. Always forgetting to charge your phone? Keep an extra power cord at the office. Always correcting the same mistakes? Ask your team to come up with a checklist so they can catch their own errors. Travel for work a lot? Create a “master packing list” so that trying to decide what to bring doesn’t require so much mental effort. Carve out time to create and tweak these kinds of systems. You might take a personal day from work to get started, and then spend an hour once a week on it to keep up; author Gretchen Rubin calls this her once-a-week “power hour.” When you start improving your systems, it creates a virtuous cycle in which you have more energy and confidence available for doing this further. By gradually accumulating winning strategies over time, you can significantly erode your problem, bit by bit.

4. You use avoid or escape methods for coping with anxiety.

People who are overloaded will have a strong impulse to avoid or escape anxiety. Avoidance could be putting off a discussion with your boss or avoiding telling a friend you can’t make it to her wedding. Escape could be rushing into an important decision, because you want to escape needing to think about it further. This can lead to a pattern of excessively delaying some decisions and making others impulsively. Avoidance and escape can also take other forms — an extra glass of wine (or three) after work, binge-watching TV, or mindlessly scrolling through Facebook. It might even be ticking less-important things off your to-do list to avoid the urgent task that’s making you anxious.

If you want to deal constructively with situations that trigger anxiety for you, you’ll need to engineer some flexibility and space into your life so that you can work through your emotions and thoughts when your anxiety is set off. With practice, you’ll start to notice when you’re just doing something to avoid doing something else.

If you can relate to the patterns described, you’re not alone. These issues aren’t personal flaws in your character or deficits in your self-control. They’re patterns that are very relatable to many people. You may be highly conscientious and self-disciplined by nature but still struggle with these habits. If you’re in this category you’re probably particularly frustrated by your patterns and self-critical. Be compassionate with yourself and aim to chip away at your patterns rather than expecting to give your habits a complete makeover or eradicate all self-sabotaging behaviors from your life.

September 19, 2018

Why CEOs Should Share Their Long-Term Plans with Investors

Fanatic Studio/Getty Images

Fanatic Studio/Getty ImagesMany people have suggested moving away from quarterly earnings reporting as a way to reduce short-termism. But such a change would probably not change how resources are allocated or businesses operate. Rather than requiring less short-term information, we believe the key to combating short-termism is to encourage companies to share more information about their long-term plans.

When asked why companies don’t talk more about the long term, CEOs often complain about the short-term orientation of investors. Similarly, investors complain that companies don’t disclose enough long-term information for them to work with. This conundrum is finally being tackled by the Strategic Investor Initiative of CECP, a CEO-level organization where one of us works. CECP has created a framework for CEOs to present the long-term strategic plans for their companies and hosts CEO Investor Forums in which to do so. To date, 19 CEOs of S&P 500 companies — such as Becton Dickinson, AETNA, 3M, PG&E, and Unilever — have presented their plans to institutional investors representing in excess of $25 trillion in assets under management. Tomorrow, another three companies — IBM, NRG Energy, and GSK — are presenting their long-term plans. The expectations for an effective long-term plan are described in SII’s Investor Letter to CEOs. Signed by leading institutional investors, the letter describes the components of a long-term plan that enables a CEO to address enduring issues of investor interest and help plug an unmet market need for information with a long-term time horizon.

CEOs have shown leadership in presenting these long-term plans; however, to date, we have not had evidence on the capital market consequences that the presentation of a long-term plan may have. We have been asked by presenting companies, those considering presenting, and other stakeholders to demonstrate real-world impacts from delivering these plans — the “what’s in it for me?” argument for why a company should deliver a long-term plan.

Given this, CECP partnered with KKS Advisors, an advisory and research firm where one of us works and the other is cofounder, to explore the information content of these plans, create a framework analyzing the content of the reports, and examine how capital market participants respond to them. Given the limited sample we have to analyze, we consider our results preliminary. However, they provide important early evidence and can be used in the future as an anchor in analyzing even more companies, as well as the long-term effects from the presentations of these plans. We collected all company strategic plans that have been presented at the CEO Investor Forum over the past four events and analyzed the subsequent returns and trading volume to understand whether there are abnormal movements in the market on the day of the event and the three-to-five-day window following the event.

We find larger capital market reactions both for stock prices and trading volume for the three and five days after the presentation of the long-term plan, compared to the typical reactions on other days, suggesting that the long-term plans communicate new information that market participants did not have before. These data also suggest that long-term plans are not mere marketing presentations or “cheap talk.” However, we find no increased propensity for Wall Street analysts to revise their forecasts in response to a long-term plan, consistent with such analysts being primarily focused on the type of short-term financial results typically delivered through the earnings call. Despite the latter finding, larger capital market reactions for both stock prices and trading volumes during the course of the event suggests that the information presented during the event is new and value-relevant for investors — that is, they are acting on it. As such, the long-term plan can be a valuable addition to the investor relations’ tool kit to enable CEOs to effectively communicate with structurally long-term investors.

We have also analyzed the content of each of the long-term strategic plans delivered at the CEO Investor Forum according to an analytical framework based on SII’s Investor Letter to CEOs, hundreds of pieces of investor feedback, and the work of collaborative initiatives, such as FCLT’s 10 elements of a long-term strategy. We then scored the quality of disclosure based on whether there is no disclosure, generic disclosure, backward-looking metrics, or forward-looking metrics for a category. A good long-term plan provides the investor with forward-looking metrics on several issues — not a generic narrative based on backward-looking information. The categories include 22 specific issues grouped into nine distinct themes: financial performance, capital allocation, industry and mega-trends, competitive positioning, risks and opportunities, corporate governance, corporate purpose, human capital, and strategic partnerships for long-term value creation.

This framework helps us analyze the content of each long-term plan presented to date — and gives us the basis for analysis of future plans. For example, plans for Becton Dickinson and Medtronic score at the top of the distribution. They are rich, specific, and actionable. Companies seem to find it easier to disclose more forward-looking metrics on themes such as competitive positioning (long-, medium-, and short-term value drivers), trends (sources of competitive advantage), and financial performance (capital efficiency and profitability). By contrast, forward-looking metrics were rarely provided for issues underlying the corporate governance theme. In fact, 58% of companies provided no information on executive compensation and how it is linked to the long-term, and 53% of companies did not disclose anything on their board composition.

Our analysis suggests that companies disclosing more actionable information around competitive positioning, corporate purpose, and the strategic partnerships in their corporate ecosystem had significantly larger market reactions than other companies when they shared their long-term plans. This suggests that, to an extent, plan content (as captured in our framework) does correlate with the capital market reactions to these plans.

We hope that this evidence will start a much-needed discussion among more CEOs to present their own long-term strategic plans, and kick-start a significant reframing of the way companies report and investors consume and act on information. We will continue analyzing the content of these plans; build a database of long-term plan content as a resource for companies, investors, and researchers; and continue to enable leading CEOs to develop best practices in delivering long-term plans. Every publicly listed company should deliver a long-term plan as part of reorienting our capital markets toward the long term.

How to Retain and Engage Your B Players

Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

Peter Dazeley/Getty ImagesWe’ve heard for decades that we should only hire A players, and should even try to cut non-A players from our teams. But not only do the criteria for being an A player vary significantly by company, it’s unrealistic to think you can work only with A players. Further, as demonstrated by Google’s Aristotle project, a study of what makes teams effective, this preference for A players ignores the deep value that the people you may think of as B players actually provide.

As I’ve seen in companies of all sizes and industries, stars often struggle to adapt to the culture, and may not collaborate well with colleagues. B players, on the other hand, are often less concerned about their personal trajectories, and are more likely to go above and beyond in order to support customers, colleagues, and the reputation of the business. For example, when one of my clients went through a disastrous changeover from one enterprise resource planning system to another, it was someone perceived as a B player who kept all areas of the business informed as she took personal responsibility for ensuring that every transaction and customer communication was corrected.

How can you support your B players to be their best and contribute the most possible, rather than wishing they were A players? Consider these five approaches to stop underestimating your B players and help them to reach their potential.

Get to know and appreciate them as the unique individuals they are. This is the first step to drawing out their hidden strengths and skills. Learn about their personal concerns, preferences, and the way they see and go about their work. Be sure you’re not ignoring them because they’re introverts, remote workers, or don’t know how to be squeaky wheels. A senior leader I worked with had such a strong preference for extroverts that she ignored or downgraded team members who were just going about their business.

You and Your Team Series

Retention

How to Lose Your Best Employees

Whitney Johnson

To Retain New Hires, Make Sure You Meet with Them in Their First Week

Dawn Klinghoffer et al.

Why Great Employees Leave “Great Cultures”

Melissa Daimler

Meanwhile, the stars on her team got plenty of attention and resources, even though they often created drama and turmoil, rather than carrying their full share of responsibility for outcomes. Some of the team members she thought of as B players started turning over after long-term frustration. When the leader and some of her stars eventually left the company, some of the B’s came back and were able to make significant contributions because they supported the mission and understood the work processes.

Reassess job fit. Employees rarely do their best if they’re in jobs that highlight their weaknesses rather than their strengths. They may have technical experience but no interest, or they could be weak managers but strong individual contributors. One leader I know had been growing increasingly more frustrated and less effective; the pressures of satisfying the conflicting demands of different departments were too much for her. Then she took a lateral move to manage a smaller, more cohesive team focused on developing new products, and was able to focus and be inspirational again once she was freed from the pressures of managing projects in such a political environment.

Consider the possibility of bias in your assignments. Women and people of color are often overlooked for challenging or high-status assignments. They’re assumed “not to be ready,” or they’re not considered because they don’t act like commonly held but stereotyped views of “leaders.” When a midlevel leader who was trying to get more exposure and advancement for one of his team members couldn’t figure out what was holding her back in the eyes of the senior leader, I raised this possibility, and we strategized multiple ways that her boss could showcase the quality and impact of her work in upcoming meetings.

Intentionally support them to be their best. Some people are their own worst critics, or have deep-seated limiting beliefs that hold them back. When one of my clients lost a senior leader and couldn’t afford to replace her at market rates, a longtime B player near the end of his career nervously filled the gap. Although he expanded his duties and kept the team going, he emphasized to both his management and himself that he wasn’t really up to the job, and most of the executive team continued to treat him that way. It was not till after he had retired, and a new senior leader had to fill his shoes, that it became clear how much he had done on the organization’s behalf. The executive team never came to grips with how much more he could have accomplished had they provided the relevant development, support, and appreciation all along.

Give permission to take the lead. In 30 years of practice, one of the most common reasons I’ve seen people hold back is if they don’t believe they’ve been given permission to step up. (The people we think of as A’s tend not to ask for or wait for permission.) Some B players aren’t comfortable in the spotlight, but they thrive when they’re encouraged to complete a mission or to contribute for the good of the company. A midlevel leader I coach is quiet, modest, and doesn’t like to make waves. She kept waiting for her new leader to lay out a vision for the future and to provide direction about how the work should be done. I asked what she would do if she was suddenly in charge. She laid out a cogent plan, and I encouraged her to present it to the new leader and ask for permission to proceed. Now she and the senior leader are moving forward in partnership.

We can’t all be A players, and it’s unrealistic to think we’ll only ever work with A players. But that may not be the appropriate goal. Instead, try using these strategies to help employees give their best, and you’ll be ensuring that your whole team can turn in an A+ performance.

Research: The Digitization of Banks Disproportionately Hurts Women Entrepreneurs

Veronica Grech/Getty Images

Veronica Grech/Getty ImagesAs banks rush to digitize their operations, many have found that closing their local branches can help maintain a high return on an otherwise pricy transformation. European banks, for example, closed over 9,000 branches in 2016, which represents a 4.6% reduction in a single year. According to our calculations, using data from the Swedish Bankers’ Association, a full one-quarter of bank branches in Sweden have shuttered over the past four years. In the United States, the total number of bank branches has dropped by 8.2% since 2013, and shrank by more than 1,700 in 2017 alone. This rapid transformation is also occurring in Asian banks, where services are being digitalized, bank functions are being centralized, and local bank branches are closing down.

Although banks consider this digitalization to be one of the main methods to increase their competitiveness, it may disrupt the relationship between banks and their venture clients. In Sweden, for example, the portion of approved bank loans to small and medium-size enterprises has decreased by 15% over the last 10 years, and roughly 60% of all ventures in need of external financing have reported difficulties in accessing financing for their investments

Many of the effects of this rapid digital change on entrepreneurship still remain unclear. But our research finds that this ongoing transformation has clear downsides for entrepreneurs in general and women in particular. It turns out that women entrepreneurs who seek to finance their ventures using bank financing are increasingly forced to find solutions elsewhere. And compared to men, women entrepreneurs are pushed into desperate and extreme types of financing.

In the past, banks’ financing of entrepreneurs has typically been dominated by relationship-based lending, in which personal meetings between an entrepreneur and a lender were at the heart of the assessment. These meetings allowed for the exchange of important information about the business model, intangible assets, future prospects, and more. This information was seldom documented formally or expressed in writing, but it allowed for an assessment of the entrepreneur’s willingness to repay the loan; their current and previous behaviors (for example, how they’ve run past businesses or how they’ve set and achieved goals); and their experience, merits, and ambitions — pieces of information that are generally considered to be strong indicators of a venture’s future performance. Having access to this kind of information enables lending to young and small ventures, which generally lack historical financial records. The practice of relationship-based lending generally requires banks and ventures to be in close proximity to one another.

In recent years, however, digitization has led a majority of banks to turn to another model to make funding decisions: a transaction-based model. As opposed to meeting with entrepreneurs, this model is largely based on financial reporting information, credit scoring, and the quality of accessible assets as collateral. Early in our research process, we suspected that gender might matter when it comes to who is approved and who is denied based on this type of reporting. Studies show that women have lower access to capital, for example. And that even when they are approved for financing, they face more demanding credit terms compared to men. The origin of these biases has been linked to gender stereotyping, where men entrepreneurs are perceived as being more ambitious and having more entrepreneurial potential than women. Such stereotypes are automatically activated when a person’s gender is identified — even on paper — and can significantly influence perceptions about whether an entrepreneur is financeable. This can also sway decisions to approve or reject loans to women and men entrepreneurs.

In 2017, we launched a research project in order to learn more about the effects of banks’ lending model transformations. We targeted a random sample of Swedish entrepreneurs (both men and women) who were applying for bank financing. We approached a total of 605 people and had a response rate of 24%. At the core of the study, we analyzed the extent to which the entrepreneurs were forced to engage in a total of 20 different informal economic activities to handle their need for financing. They include not paying taxes or invoices on time, breaking credit agreements, the use of undocumented workers and trades in services. We combined this data with alternative and complementary secondary bank data in order to control and mitigate confounding effects of the size, type, and age of the ventures; their capital need; and the educational level of the entrepreneur and employees.

Our results show that women face increased difficulty in accessing bank financing, and specifically that women’s entrepreneurship suffers heavily from the recent transformation among banks. In short, women entrepreneurs showed more of a need to engage in informal economic activities than men.

Why? Gender provides an “implicit background identity” for a banker when assessing an entrepreneur. This identity can bias financing decisions. But if the banker meets with the entrepreneur, that identity may change. Thus, a lack of interactions between banks and entrepreneurs allows for initial stereotypes to frame bankers’ perceptions of entrepreneurs, which may be amplified when no actual social interactions occur that could change these stereotypes.

There’s an argument that the centralization of financing decisions could improve conditions for women entrepreneurs; human distance and computer algorithms may solve the problems with human interference. Our findings call this into question, however, as the women entrepreneurs in our study were often placed outside the formal economy for financing their ventures.

To begin to address this issue, banks may need to revisit their recent rapid change in decision models to strive for equal opportunities when financing entrepreneurship. Women entrepreneurs, for their part, also must be selective when choosing a bank, carefully considering the bank’s decision model and building relationships with bankers in an attempt to overcome stereotyping and gender-biased access to financing. What is clear is that we need to know more about what business opportunities are lost — as well as how and why this loss occurs — when banks adopt transaction-based lending models.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers