Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 796

October 5, 2018

3 Common Mistakes That Can Derail Your Team’s Predictive Analytics Efforts

Scott Barbour/Getty Images

Scott Barbour/Getty ImagesWith today’s high demand for data scientists and the high salaries that they command, it’s often not practical for companies to keep them on staff. Instead, many organizations work to ramp up their existing staff’s analytics skills, including predictive analytics. But organizations need to proceed with caution. Predictive analytics is especially easy to get wrong. Here are the first three “don’ts” your team needs to learn, and their corresponding remedies.

1) Don’t Fall for Buzzwords — Clarify Your Objective

You know the Joe Jackson song, “You Can’t Get What You Want (Till You Know What You Want)”? Turn it on and let it be your mantra. As fashionable as it is, “data science” is not a business objective or a learning objective in and of itself. This buzzword means nothing more specific than “some clever use of data.” It doesn’t necessarily refer to any particular technology, method, or value proposition. Rather, it alludes to a culture — one of smart people doing creative things to find value in their data. It’s important for everyone to keep this top of mind when learning to work with data.

Under the wide umbrella of data science sits predictive analytics, which delivers the most actionable win you can get from data. In a nutshell, predictive analytics is technology that learns from experience (data) to predict the future behavior of individuals in order to drive better decisions. Prediction is the Holy Grail for more effectively executing mass scale operations in marketing, financial risk, fraud detection, and beyond. Predictive analytics empowers your organization to optimize these functions by flagging who’s most likely to click, buy, lie, die, commit fraud, quit their job, or cancel their subscription — and, beyond predicting people, by also foretelling the most likely outcomes for individual corporate clients and financial instruments. These predictions directly inform the action to take with each individual, e.g., by marketing to those most likely to buy and auditing those most likely to commit fraud.

Insight Center

Scaling Your Team’s Data Skills

Sponsored by Splunk

Help your employees be more data-savvy.

In their application to these business functions, predictive analytics and machine learning (ML) are synonyms (in other arenas, machine learning also extends to tasks such as facial recognition that aren’t usually called predictive analytics). Machine learning is key to prediction. The accumulation of patterns or formulas ML derives (learns) from the data — known as a predictive model — serves to consider a unique situation and put odds on the outcome. For example, the model could take as input everything currently known about an individual customer and produce as output the probability that that individual will cancel their subscription.

When you begin to deploy predictive analytics with your team, you’re embarking upon a new kind of value proposition, and so it requires a new kind of leadership process. You’ll need some team members to become “machine learning leaders” or “predictive analytics managers” — which signify much more specific skill sets than the catch-all “data scientist,” a title that’s guilty of vagueries and overhype (but, do allow them that title if they like, as long as you’re on the same page).

2) Don’t Lead with Software Selection — Team Skills Come First

In 2011, Thomas Davenport was kind enough to keynote at the conference I founded, Predictive Analytics World. “It’s not about the math — it’s about the people!” he absolutely bellowed at our captivated audience, more loudly than I’d ever heard since high school, when teachers had to get control of a classroom of teens.

Tom’s startling tone struck just the right note (a high D flat, to be exact). Analytics vendors will tell you their software is The Solution. But the solution to what? The problem at hand is to optimize your large-scale operations. And the solution is a new way of business that integrates machine learning. So, a machine learning tool only serves a small part of what must be a holistic organizational process.

Rather than following a vendor’s lead, prepare your staff to manage machine learning integration as an enterprise endeavor, and then allow your staff to determine a more informed choice of analytics software during a later stage of the project.

3) Don’t Leap to the Number Crunching — Strategically Plan the Deployment

The most common mistake that derails predictive analytics projects is to jump into the machine learning before establishing a path to operational deployment. Predictive analytics isn’t a technology you simply buy and plug in. It’s an organizational paradigm that must bridge the quant/business culture gap by way of a collaborative process guided jointly by strategic, operational, and analytical stakeholders.

Each predictive analytics project follows a relatively standard, established series of steps that begins first with establishing how it will be deployed by your business and then works backwards to see what you need to predict and what data you need to predict it, as follows:

Establish the business objective — how the predictive model will be integrated in order to actively make a positive impact on existing operations, such as by more effectively targeting customer retention marketing campaigns.

Define a specific prediction objective to serve the business objective, for which you must have buy-in from business stakeholders — such as marketing staff, who must be willing to change their targeting accordingly. Here’s an example: “Which current customers with a tenure of at least one year and who have purchased more than $500 to date will cancel within three months and not rejoin for another three months thereafter?” In practice, business tactics and pragmatic constraints will often mean the prediction objective must be even more specifically defined than that.

Prepare the training data that machine learning will operate on. This can be a significant bottleneck, generally expected to require 80% of the project’s hands-on workload. It’s a database-programming task, by which your existing data in its current form is rejiggered for the needs of machine learning software.

Apply machine learning to generate the predictive model. This is the “rocket science” part, but it isn’t the most time-intensive. It’s the stage where the choice of analytics tool counts — but, initially, software options may be tried out and compared with free evaluation licenses before then making a decision about which one to buy (or which free open source tool to use).

Deploy the model. Integrate its predictions into existing operations. For example, target a retention campaign to the top 5% of customers for whom an affirmative answer to the “will the customer cancel” question defined in (ii) is most probable.

There are two things you should know about these steps before selecting training options for your predictive analytics leaders. First, these five steps involve extensive backtracking and iteration. For example, only by executing step (iii) might it become clear there isn’t sufficient data for the prediction objective established in step (ii), in which case it must be revisited and modified.

Second, at least for your first pilot projects, you’ll need to bring in an external machine learning consultant for key parts of the process. Normally, your staff shouldn’t endeavor to immediately become autonomous hands-on practitioners of the core machine learning, i.e., step (iv). While it’s important for project leaders to learn the fundamental principles behind how the technology works — in order to understand both its data requirements and the meaning of the predictive probabilities it outputs — a quantitative expert with prior predictive analytics projects in his or her portfolio should step in for step (iv), and also help guide steps (ii) and (iii). This can be a relatively light engagement that keeps the overall project cost-effective, since you’ll still internally execute the most time-intensive steps.

Good luck, and happy predicting.

Rethinking How Medicaid Patients Receive Care

Hero Images/Getty Images

Hero Images/Getty ImagesIn 2015, CareMore embarked on a journey to transform care delivery in Medicaid with the aim of leveraging its 20-year history in providing comprehensive care for seniors under Medicare. To many at the time, we were fools.

Critics outside of CareMore issued an ugly forecast: Our resource-intensive approach to care would never survive on Medicaid’s meager reimbursement levels. Great physicians would never choose to treat Medicaid patients. Medicaid’s ever-shifting eligibility requirements would disrupt any efforts to treat patients for years at a time. And, if we somehow overcame those hurdles, the patients themselves were too barricaded by socioeconomic barriers or structural inequalities to respond to anyone’s well-intentioned efforts to treat them.

There were internal doubts as well. CareMore’s longtime focus had been providing patient-centered, managed care to seniors in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Virginia under Medicare Advantage. Many of the organization’s veterans saw our Medicaid ambitions as an unwise detour into treacherous territory. How would we deliver care to a population overburdened with severe mental illness, food insecurity (the lack of consistent access to enough food to lead an active, healthy life) and early-onset chronic diseases — and do so in locations as disparate as Tennessee and Iowa?

Insight Center

The Future of Health Care

Sponsored by Medtronic

Creating better outcomes at reduced cost.

Nonetheless, CareMore’s leaders decided to move ahead and launched a Medicaid care-delivery program in Memphis and Des Moines, serving 8,000 to 10,000 patients in each market. We described our early progress in this 2015 HBR article. Now, as we begin to scale our care-delivery model to multiple new geographies, we’d like to share what more we’ve learned from our experiences in the two initial markets — lessons we think are applicable to other populations as well.

Comprehensive, relationship-based primary care. Relatively few of Medicaid’s 67 million beneficiaries have a primary care doctor. Many distrust the American medical profession, but many of those who would entrust a doctor with their care can’t afford one or face logistical or geographic barriers to finding one.

Consequently, we knew that in order to serve the Medicaid population well, we needed to create convenient and completely free access to comprehensive care, staffed by clinicians who empathized deeply with our patients’ needs and who had the resources to address fundamental barriers to health.

The first step was finding caregivers dedicated to ministering to the underserved. Some of our earliest hires had lacked the true compassion needed to earn the trust of patients. Not only did this small complement of clinicians alienate patients, but they also drove away our best hires: those who had joined CareMore so they could pour their heart and soul into patient care.

So, we made radical team changes and started again with a new set of employee-screening techniques. Chief among them were behavioral-interview methods to uncover candidates’ intrinsic motivations and biases. Asking simple questions, like “tell me about a time where you helped someone change his or her approach to health,” we found, could compel candidates to share stories of guiding patients to life-changing decisions or, conversely, reveal a candidate’s contempt for individuals struggling with addiction. We also invested significant leadership time in performing final interviews for all roles — from medical assistants to physician leaders — to ensure that each team member would strengthen the team’s dedication. We now speak of finding team members who were “CareMore before they joined CareMore” — in other words, people have already demonstrated our philosophy of care in their professional journeys.

Using this approach to build each new Medicaid team, we then armed the primary care team with the operating structure, data, and incentives needed to create engagement with our patients wherever they are, enveloping them with compassion and the latest in evidence-based care.

Our primary care clinicians operate in multidisciplinary teams. Each team is assigned a group of patients near its clinic for direct oversight, to identify new problems they are facing, and trigger interventions by the right team members. For example, during a clinical huddle, a pharmacist may identify the potential for a medication complication and trigger CareMore’s mobile team to visit the patient’s home that day to review the medications being taken. CareMore teams also organize transportation for patients to medical appointments and offer same-day visits, extended hours, and online video consultations to create multiple, convenient access points for patients.

We also equip the teams with data-rich dashboards that monitor their patients’ engagement, satisfaction, and, of course, health metrics, while also tracking broader population-level trends in clinical outcomes and avoidable — and often unnecessary or harmful — procedures and hospitalizations. These dashboards combine data from health plan partners, such as claims data and approvals for hospitalizations, with electronic-medical-record data, and provide a comprehensive, real-time view of key metrics in quality, cost, and experience. As a result, these dashboards enable CareMore clinical teams to dynamically adjust their outreach and clinical priorities, shifting attention to where they can provide the most benefits to patients.

Last, in order to align our employees’ performance with our patients’ health, up to 35% of staff compensation is based on their ability to achieve engagement, satisfaction, and clinical outcome goals. Put simply, they’re rewarded for doing well by our patients.

Collaborative behavioral health. As many as 25% to 30% of adults on Medicaid suffer from serious mental-illness and substance-abuse disorders. We have found that behavioral-health issues, even when identified, are frequently misdiagnosed and mismanaged by a shifting cast of clinicians in inpatient and outpatient settings. To better serve our patients, we wove our behavioral health team’s expertise into everything we do.

Our psychiatric and therapy teams directly care for patients with more severe conditions and provide high-acuity care such as long-acting injectable antipsychotics. However, they spend equal time consulting with the primary care team on their patients’ behavioral health issues, ensuring that we find the right diagnoses and treatment options for the entire patient population.

In addition to our frontline caregivers, we add a critically-important layer of clinicians known as care management specialists, who support patients through transitions from hospitals back to their home. They visit patients with behavioral-health needs during inpatient and residential psychiatric care episodes, connecting them with the primary care team, specialists, and other resources after discharge so they are effectively engaged in continuous care. These specialists also longitudinally track patients with high-risk medical conditions such as heart failure or diabetes.

As a result of our collaborative behavioral-health model, over 75% of patients who saw CareMore’s behavioral health team in Iowa in 2017 also saw our primary care team. And in Tennessee, we reduced behavioral-health-related readmissions for our Memphis population from 40% in 2016 to 13% in 2017 and 2018.

Community and patient engagement focused on social needs. Placing clinics in convenient locations for patients isn’t enough; care delivery organizations also need to go further in meeting Medicaid patients where they live, work, and access other services. Accordingly, CareMore deploys specialists known as community health workers — often experienced social workers who act as the worried family member for high-risk patients. These specialists are trusted members of a community who have a deep understanding of the local context — be it historical, social, economic, or health-related — and how we can break through barriers that are often unseen by other health care providers.

The team reaches out to patients by phone and in person, finding them at home and alternative sites such as jails and shelters. On average, our community health workers will try to reach a high-risk patient seven times before successfully engaging them in a conversation about their health care. In each engagement, community health workers strive to understand a patient’s beliefs and social context. By forming this relationship first, community health workers can then identify concerns around housing, food, or finances that patients are sometimes too uncomfortable to convey and help them overcome that stigma to access the social and clinical services they need.

Through repeated outreach conversations in Memphis, for example, our community health team identified a patient’s primary barrier to breaking a toxic cycle of repeated hospitalizations. The obstacle: a custody battle for her child in which the woman’s behavioral health had become an issue for the court. The community health worker helped her obtain legal support, and her CareMore primary care physician submitted a letter to the court attesting to the improvement in the patient’s behavioral-health condition. The mother won custody of her child, reunited her family, and we saw her hospitalizations and unnecessary utilization plummet to zero.

Removing silos between inpatient care and the community. For many patients on Medicaid, a hospitalization is an isolating and risky interlude that threatens to undermine a tenuous balance among work, family obligations, and financial resources while imposing new health concerns and treatment plans. To ensure a return to health, CareMore actively manages patients during hospitalizations and in the crucial hours and days following their discharge. We do this by staffing clinicians who wear the CareMore title of “extensivists”: physicians who care for patients not only during hospital episodes but also through the entire post-hospitalization period, in rehabilitation facilities and the home, until the patient is ready to return to primary care.

In some geographical areas, we have so few hospitalized patients that it makes little economic sense to employ extensivists. In these instances, CareMore’s care management team meets patients during hospitalizations in person on a regular basis to form relationships and coordinate care during the post-hospitalization period.

Because of our approach to connecting hospitalizations to follow-up care and oversight, CareMore’s Tennessee extensivists were the best-performing clinicians at Methodist University’s main Memphis hospital site in 2017 as measured by observed versus expected hospital length of stay and readmission rates. The upshot: Our extensivist model helped patients get home faster and come back to the hospital less often.

Similarly, our care management team meets 80% of hospitalized patients in Des Moines in person on a weekly basis. As a result of this engagement, three-quarters of those patients follow up in our care center within a week after discharge.

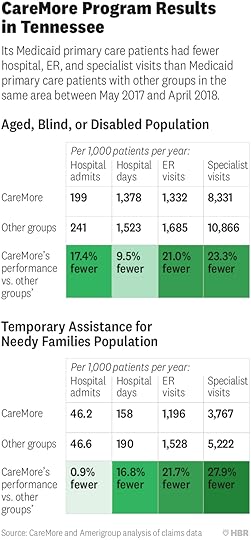

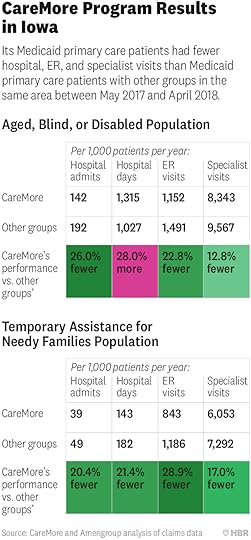

Our results. In Tennessee and Iowa, CareMore has delivered outcomes that have significantly improved care and reduced its cost. From May 2017 to April 2018, CareMore’s Medicaid patients in Tennessee experienced 10% to 17% fewer days in the hospital, 21% to 22% fewer ER visits, and 23% to 28% fewer specialist visits than other Medicaid managed care beneficiaries in the same geography, across Medicaid eligibility categories.

In Iowa, the impact has been similarly sizable for those on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) support and in the ABD cohort. These differences in avoidable utilization produced millions of dollars annually in cost of care savings for Tennessee and Iowa.

Next Steps

CareMore’s robust and durable outcomes against other primary care groups have led its leaders to aggressively scale our model to new geographies, including Washington, D.C.; Texas; and New York. This success in extending CareMore’s core principles to new populations has also led it to launch a division dedicated to designing, testing, deploying, and scaling care models and clinical innovations that radically improve population outcomes. We intend to address food insecurity through home meal delivery, bring hospital-level care into the home, and equip behavioral-health teams to provide medication-assisted treatment onsite for substance abuse.

We believe that we are proving that Medicaid managed care plans and care delivery organizations can be dramatically improved. Those improvements, in turn, can be extended to improve the cost and quality of care to other populations. The key is designing care models that cater to a population’s special needs.

The Virtual Work Skills You Need — Even If You Never Work Remotely

Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesMaintaining strong, productive relationships with clients and co-workers can be challenging when you never see the person you’re working with. Yet, it is common to have ongoing work relationships – sometimes lasting years — with people you’ve never met in person.

We often think of “virtual work” as working with someone located outside an office, or in another city or country. This type of work is on the rise: a 2017 Gallup report found 43% of American employees work remotely; in another survey, 48% of respondents reported that a majority of their virtual teamwork involved members from other cultures.

However, virtual work also encompasses how we are turning to technology to conduct business with nearby colleagues, sometimes within the same building or campus. At a large consumer-products firm where we’ve been conducting research, an HR director recounted the changes she witnessed in employees located in two buildings a few miles apart. “Ten years ago, we would regularly drive between buildings to meet each other, but today, we almost never do; meetings are conducted by videoconference and everything else is handled on e-mail and IM.”

In our interview and survey research, we find that people tend to significantly underestimate the proportion of their work that is virtual, largely because they believe virtual work occurs outside the office. But it’s important for us to recognize the true extent of virtual work, because successful virtual work demands a different set of social and interpersonal skills and behaviors than face-to-face work.

Research consistently indicates that virtual work skills – such as the ability to proactively manage media-based interactions, to establish communication norms, to build social rapport with colleagues, and to demonstrate cooperation – enhance trust within teams and increase performance. Our surveys indicate that only about 30% of companies train employees in virtual work skills, but when they do, the training is more likely to focus on software skills and company policies than on social and interpersonal skills. Our findings are similar to those of a 2006 survey of HR leaders on training of virtual teams, suggesting that while technology and virtual work itself has advanced dramatically in recent years, our preparation to work virtually has not.

Our recent review of 30 years of virtual work research shows that the most effective workers engage in a set of strategies and behaviors that we call “virtual intelligence.” Some people tend to be naturally more adept at working virtually than others; yet, everyone can increase their virtual intelligence. Two specific skill sets contributing to virtual intelligence are 1) establishing “rules of engagement” for virtual interactions, and 2) building and maintaining trust. These skill sets are relevant to all individuals who conduct virtual work, including coworkers in the same office who interact virtually.

Establishing “rules of engagement”

When working with someone face-to-face, the “rules of engagement” for your work together most likely evolve naturally, as you learn the best times of day to connect, where to hold productive meetings, and the most effective meeting format. In virtual work, however, these “rules of engagement” typically require a dedicated conversation. At a minimum, virtual colleagues should discuss the following rules around:

Communication technology. Once you know you’ll be working virtually with someone on a regular basis, initiate a short conversation about their available technology, and agree on the best means of communication (e.g., “We’ll e-mail for simple, non-urgent matters, but get on Skype when there is something complex that might require us to share screens. Texting is fine if we need to get in touch urgently, but shouldn’t be used day-to-day.”)

Best times to connect. You might ask your virtual co-worker, “What times of day are typically better to call or text? Are there particular days of the week (or month) that I should avoid?” Establishing this rule early in a virtual work relationship both establishes respect for each other’s time, and saves time, by avoiding fruitless contact attempts.

How best to share information. If you’re collaborating on documents or other electronic files, establish a process to ensure you don’t inadvertently delete updates or create conflicting versions. File-sharing services such as Dropbox can help monitor revisions to jointly-owned documents (often called “version control”), but it is still wise to establish a simple protocol to avoid lost or duplicated work.

Building and maintaining trust

Two types of trust matter in virtual work: relational trust (trust that your colleague is looking out for your best interests), and competence-based trust (trust that your colleague is both capable and reliable).

To build relational trust:

Bring a social element into the virtual work relationship. Some people do this by starting conversations with non-work-related questions, such as “How are things going where you are?” or “How was your weekend?” Avoid making questions too personal, and don’t overwhelm your colleague with extensive details of your life. Keep it simple and sincere, and the conversation will develop naturally over time.

Let your enthusiasm and personality show in your virtual communications. Keep it professional, but try adding a little of your own ‘voice’ to give your virtual colleague a sense of who you are, just as they would have in a face-to-face meeting.

To build competence-based trust:

Share your relevant background and experiences, indicating how these will help you support the current project. For example, on a new-product development project, you might say, “I’m really looking forward to contributing to the market analysis, as it focuses on a market that I researched last year on another project.”

Take initiative in completing tasks whenever possible and communicate that you’re doing so with periodic update e-mails. Doing this shows commitment to the shared task.

Respond to e-mail quickly and appropriately. We risk obviousness in making this point, but many virtual work relationships fail due to inconsistent e-mail communication. Silence works quickly to destroy trust in a virtual colleague. We recommend replying to non-urgent e-mails within one business day (sooner if it’s urgent). If you need more time, send a quick acknowledgement of the e-mail, letting your colleague know when you will reply.

As the use of technology for all types of communication has become ubiquitous, the need for virtual work skills is no longer limited to telecommuters and global teams; it now extends to those of us whose work never takes us out of the office. Making a concerted effort to develop these skills by setting up rules of engagement and establishing trust early can feel uncomfortable, especially for people new to the idea of virtual work. Most of us are used to letting these dynamics evolve naturally in face-to-face relationships, with little or no discussion. Yet, workers with higher virtual intelligence know that these skills are unlikely to develop without explicit attention, and that making a short-term investment in developing the virtual relationship will yield long-term benefits.

Research: Career Hot Streaks Can Happen at Any Age

Driendl Group/Getty Images

Driendl Group/Getty ImagesIn science, 1905 is known as the annus mirabilis, or “miracle year,” the period when Albert Einstein, at the age of 26, published several discoveries that changed physics forever. By the summer of that year he’d explained Brownian motion, discovered the photoelectric effect (for which he won a Nobel Prize), and developed the theory of special relativity; then, before the year ended, he wrote the world’s most famous equation: E = mc².

What happened for Einstein in 1905 can be described as a “hot streak,” or burst of seemingly miraculous success and impact. Our understanding of creative careers to date has suggested they’re unlikely to include hot streaks. For example, my earlier co-authored work found that a scientist’s biggest research hit occurred completely randomly in their sequence of published works: It could be, with equal likelihood, the very first work, the last, or any one in between. We called this phenomenon the “random impact rule.”

While intriguing by itself, the random impact rule raises puzzling implications: What happens after we finally produce a breakthrough? Indeed, if every work in a career is like a random lottery draw, then one’s next work after a hit may be more mediocre than spectacular, reflecting regression toward the mean.

But this is hard to believe. Most of us — including me — would like to believe that if we produced a big hit, it would help us produce more hits afterwards. After all, we know that winning begets more winning. So are we really regressing toward mediocrity after we break through? To answer these questions my student Lu Liu and I along with other collaborators studied the careers of about 30,000 scientists, artists, and film directors. We used a given work’s number of citations (as provided by the Web of Science), auction price, and IMDB rating, respectively, as measures of quality and impact. We find that across these diverse careers, the random impact rule holds firm.

In fact, it’s not just the biggest hit that occurs at random: The second-biggest and third-biggest also hit randomly. This finding paints an unpredictable view of creativity, with an outsized role of chance in individual success. If our careers are indeed like lotteries, should we just keep drawing and hope for the best?

This, thankfully, is an incomplete reading of the data, as we found upon examining the relative timing of hit works. Specifically, we asked: Given when someone produced their best work, when would their second-best work be? We find that knowing the timing of one’s best work points to when their next best works will arrive: They’re just around the corner. So, while the timing of most-successful works in a career is random, their relative timing is very predictable. In other words, creative careers are characterized by bursts of high-impact works clustered together in sequence. The result begs a key question: Why?

We found that the most compelling explanation is the existence of hot streaks: across all creative domains we studied, individuals enjoy specific periods of outsized relative impact that occur randomly in any one person’s career. Hot streaks are ubiquitous: for each domain we studied, about 90 percent of individuals had at least one hot streak.

So it wasn’t just Einstein’s miracle year of productivity, but The Lord of the Rings series for director Peter Jackson, the “drip period” for painter Jackson Pollock, or the time Vincent Van Gogh spent in South France in 1888, a year in which he produced renowned works including The Yellow House, Van Gogh’s Chair, Bedroom in Arles, The Night Café, Starry Night Over the Rhone, Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers, and others.

We also found that hot streaks usually last for short periods: For artists and film directors, it’s about five years; for scientists, four. Moreover, the timing of the hot streak is random. Hence while periods of relative success were common, there was no way to predict when these would emerge in a given career, in line with the random impact rule uncovered earlier. Unexpectedly, hot streaks were not associated with greater productivity. Thus we don’t produce more during hot streaks than we typically would, but what we create is substantially better than our remaining body of our work.

What do our findings mean for professionals and the ecosystems they inhabit? In the scientific community, for example, projected impact is critical for hiring, advancement, grant-making, and other decisions. But the same is true of most domains, including business. Our research suggests that decision-makers should consider incorporating the notion of hot streaks into their calculus, if polices are to identify and nurture individuals more likely to have lasting impact.

But perhaps the most important — and uplifting — implication is for the individual innovators out there striving to make their mark on the world. The conventional view is that an individual’s best work will likely happen in their 30s or 40s, when they have a solid base of experience, along with the energy and enthusiasm to sustain high productivity; once we pass the mid-career point, hopes for breakthroughs start to dim. Our findings indicate that the hot streak may emerge with any work you put out, resulting in a near-term cluster of relative successes. Your big break, it appears, may arrive at any time in your career.

In other words, there is hope: Each new gray hair, literal or figurative, does not by itself make us obsolete. As long as you keep putting work out into the world, one project after another, your hot streak could be just around the corner.

Bear in mind, however, that while the hot streak phenomenon seems universal in the domains we studied, we don’t yet know why it happens in a given career, or what triggers it. Indeed, the only certainty is this: The fate of your career rests largely in your own hands, because one sure way to prevent a hot streak is to stop producing altogether. While it may be true that older people are less likely to break through than their younger counterparts, we found that this is not because age and creativity are intertwined. It’s simply because we try less in later life-stages.

October 4, 2018

Remote Workers

How does working remotely complicate your career? In this episode of HBR’s advice podcast, Dear HBR:, cohosts Alison Beard and Dan McGinn answer your questions with the help of Siobhan O’Mahony, a professor at Boston University Questrom School of Business. They talk through how to advance in your job when you’re not in the building, deal with a problematic colleague you never see, and manage teams in other offices.

Listen to more episodes and find out how to subscribe on the Dear HBR: page. Email your questions about your workplace dilemmas to Dan and Alison at dearhbr@hbr.org.

From Alison and Dan’s reading list for this episode:

HBR: A Study of 1,100 Employees Found That Remote Workers Feel Shunned and Left Out by Joseph Grenny and David Maxfield — “Overall, remote employees may enjoy the freedom to live and work where they please, but working through and with others becomes more challenging. They report that workplace politics are more pervasive and difficult, and when conflicts arise they have a harder time resolving them.”

HBR: A First-Time Manager’s Guide to Leading Virtual Teams by Mark Mortensen — “First things first: don’t panic. Remember that global, virtual, distributed teams are composed of people just like any other team. The more you and your team members can keep this in mind, the better your results will be. As the manager, encourage everyone to engage in some perspective taking: think about how you would behave if your roles were reversed. This is a small way of reminding your team that collaboration isn’t magic, but it does take some effort.”

HBR: Why Remote Work Thrives in Some Companies and Fails in Others by Sean Graber — “Successful remote work is based on three core principles: communication, coordination, and culture. Broadly speaking, communication is the ability to exchange information, coordination is the ability to work toward a common goal, and culture is a shared set of customs that foster trust and engagement. In order for remote work to be successful, companies (and teams within them) must create clear processes that support each of these principles.”

HBR: How to Collaborate Effectively If Your Team Is Remote by Erica Dhawan and Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic — “Old school birthday cakes are still important for remote teams. Creating virtual spaces and rituals for celebrations and socializing can strengthen relationships and lay the foundation for future collaboration. Find ways to shorten the affinity distance. One company we worked with celebrated new talent by creating a personal emoji for each employee who had been there for six months.”

HBR: The Secrets of Great Teamwork by Martine Haas and Mark Mortensen — “Distance and diversity, as well as digital communication and changing membership, make them especially prone to the problems of ‘us versus them’ thinking and incomplete information. The solution to both is developing a shared mindset among team members—something team leaders can do by fostering a common identity and common understanding.”

What to Do If Your Team Is Too Busy to Take On New Work

STR/Stringer/Getty Images

STR/Stringer/Getty ImagesWhen a manufacturing line in a factory is running efficiently, one can see lines of robotic arms working synchronously, conveyor belts moving smoothly, and goods being produced. Unfortunately, when it comes to knowledge work, it’s much tougher to get an understanding of how much a team of people is producing.

There comes a point in every organization when if you want to keep growing, you simply have to hire more people. But it can be difficult to know when you’ve reached that point. For example, every year, during the annual business planning cycle I always notice that managers propose a larger budget. When I have asked “Why can’t we do more with our existing budget?” the answer is usually, “My team is telling me that they’re all too busy with existing initiatives and do not have capacity to take on anything new.”

Project overload is real. But as a leader, how do you know whether your team is really needs more resources, or whether they could be working more efficiently?

To answer this question, the first thing that a leader should do is to understand how their teams spend their time. A simple way to get a holistic view of this is to ask people to explain three things:

The key activities each person performs as their primary job responsibilities

The amount of time in a given week each person spends on these key activities

The types of activities that are above and beyond core job functions or special projects

Once you’ve collected this data, the next step is to focus on the areas that the team is spending the most amount of time. To find more time, leaders will need to identify opportunities to eliminate work, reduce workload, or improve productivity by working closely with their teams.

Eliminate Work: Are there tasks that the team is doing that are no longer needed?

When a business is growing fast, it is often not the first priority to really take a step back and understand if all efforts are truly being focused on driving current business priorities. For Instance, in one of my past organizations, we uncovered that team members were spending up to 40% of their time on internal projects rather than customer-facing projects.

To figure out why, we asked team members to provide the names of all their projects, the purpose of these projects, when the projects had started, and how close they were to completion. We uncovered that the top reason people were spending so much time on internal projects was that these had launched when these initiatives were a business priority. As the overall business focus changed to be more customer-focused, leaders including myself had not explicitly communicated that these internal projects should be wound down. As a result, team members continued to work on projects that were inconsistent with our current business goals.

By eliminating these lower-value internal projects, our teams were able to engage with our customers more deeply, leading to increased product adoption rates. We were also able to invest 20% of the teams’ time in projects that were aligned with our new strategy.

Reduce Workload: What can we do differently to reduce the volume of tasks being performed by the team?

A perennial management challenge is figuring out how to minimize the amount of time employees spend on low-value tasks — the repetitive, transactional tasks that have to get done, but often seem to take up an inordinate amount of time. It’s not possible to eliminate all transactional tasks, but by diving into the details of existing processes, leaders can challenge the status quo and help simplify processes that reduce these tasks.

For instance, one of our teams was responsible for launching online advertising campaigns. They’d work with our customers to understand the goals of the campaign and ensure that we had the right creative assets to launch the campaign. The team was spending a lot of time waiting for customers to respond to their emails — over 25% of their time was being spent simply following up.

As we worked to understand the process, we learned that process was comprehensive and resulted in launching error-free campaigns. However, when we dug deeper to understand why we needed so many customer approvals, the reasons were rooted in the product’s past. When this product was originally launched, customer awareness was low. To ensure that all campaigns launched correctly, the team had created a process that had all the checks and balances. Even though the product had improved significantly and customers now understood how to employ the product, we had not updated the process.

We changed the process where all customers with standard campaigns would have 48 hours to disapprove our execution proposal. By making the approvals passive for our standard campaigns, we not only eliminated tasks that our teams found tedious but we also shortened the campaign launch time by 48 hours on average. These changes allowed each team to launch more campaigns.

Improve Productivity: What can we do to complete tasks more quickly?

While process improvements can drive some productivity increases, the biggest productivity improvements are often a result of automating groups of tasks. When automation is coupled with process changes, the resulting impact can be substantial.

For instance, one of our teams was responsible for working with our customers to help them integrate with our product. It typically took five weeks to do this, which seemed like an unduly long amount of time. When we asked why, the answer surprised us. The customers would start to write their integrations and whenever they had a problem they would request a meeting. We found that not only were a lot of our customers’ questions very similar, but our customers would also schedule a call and then share the details of the problem during the call. This resulted in follow-up meetings to completely resolve the question. The team was challenged to use technology to solve this problem and they came up with an ingenious solution. They wrote a software tool that would check for all the common errors. They then changed the customer engagement model — instead of just describing the process of integration, they would leave the first conversation by giving the error checking tool to the customer. We established a new protocol, so that when customers ran into issues, they would use the tool and send the report from the tool before we scheduled the call. These simple tweaks allowed us to shave a total of 30 hours (nearly a full week) from the total integration time. Our team members were able to engage with a larger number of customers to meet our growing needs.

Most people are usually doing their best — from their perspective, they have the best interests of the business at heart. Doing more with less may sound very challenging, especially when business is growing and the bar for customer expectations is rising. To create more time in people’s schedules, managers need to engage with their teams to deeply understand daily operations. This will allow teams to scale the business and meet growing customer expectations by doing more with less. And if the three steps above aren’t working, managers may need to admit that it’s time to hire more people.

How Doctors Can Be Better Mentors

STOCK4B-RF/Getty Images

STOCK4B-RF/Getty ImagesBeing a good doctor is a lot like being a good mentor. Just as clinicians have an ethical duty to act in the best interest of their patients, mentors have a similar duty towards their mentees. In our clinical and academic lives (where we’ve treated countless patients and mentored hundreds of doctors-in-training) we strive to do both as well as we can. Along the way, we’ve found that practicing mindfulness — being patient, focused on the moment, and accepting of events as they unfold — is important.

Consider, first, how similar doctoring and mentoring can be. In both, the relationship is asymmetric: the doctor holds the power or authority, and has most of the expertise, while the patient or mentee seeks guidance and advice. The doctor has — or should have — only the patient’s or mentee’s interests and well-being in mind. And when true malpractice occurs — either by a physician or mentor — the aggrieved party has much more to lose.

Insight Center

The Future of Health Care

Sponsored by Medtronic

Creating better outcomes at reduced cost.

We have had the good fortune to have many mentees come to us for advice. And just as we have honed our clinical skills by reflecting on patient outcomes, we have evolved a similar studied approach for mentoring. In both, we have learned how to incorporate mindfulness to focus on what’s best for the mentee and his or her career. Here are the guiding principles we try to follow.

#1: Be available

People in healthcare — and especially good mentors — are busy. Many find themselves engulfed by meetings, speaking engagements, and travel. Being attentive to a mentee in the midst of these engagements is challenging but critical. We suggest the following approaches:

Appreciate that some is better than none. As schedules fill, we recommend shorter meetings over no meetings. There is great utility in a 30-minute — even 15-minute — meeting if a traditional 60-minute mentoring meeting isn’t possible. Shorter meetings will also force your mentee to get to the point and will require you to be less long-winded.

Find alternatives to the face-to-face meeting. A brief after hours call, text message, or email can help your mentee stay on track and prevent you from being the rate-limiting step in their productivity. Take advantage of video conferencing and smart phones when you are away on travel (we’ve done FaceTime with mentees from the road). And if that doesn’t work, resort to good old-fashioned email.

Be fully present. Just because you can speak with your mentee in person, by phone or by video does not mean that you are truly communicating. This also holds during routine meetings in your office. Being a mindful mentor means demonstrating to your mentee that for the next X minutes, they are all that matters. And when we find ourselves distracted during the discussion by thoughts about other tasks or the meeting we need to go to next, we silently remind ourselves: Be here, now.

#2: Know your role

Ask yourself, “What role does my mentee need me to play?” Your relationship need not only take the form of a traditional and general mentoring role involving a seasoned expert who provides guidance and wisdom to a junior person. There are other three other key archetypes to consider: coach, sponsor, and connector. The “coach” teaches the junior person how to improve in a particular skill, such as finding a job or performing a particular medical procedure. The “sponsor” helps boost mentees by promoting them for specific awards or positions, honorific societies, or other high-profile positions. Sponsors risk their own reputations when vouching for mentees — thus, they look for highly successful individuals. The “connector” serves as a master networker who pairs mentors, coaches, and sponsors with mentees. Malcolm Gladwell in The Tipping Point aptly describes connectors as multipliers that link us up with the world.

Ideal mentors are mindful about their role and how they should play it. They also anticipate what the mentee needs even before the he or she is aware of such a need. For example, a year — or more — before the junior person is going up for promotion, the mentor begins to reach out to national colleagues recommending the mentee for talks at peer institutions, thereby acting in the role of sponsor. Whether you are mentoring, coaching, sponsoring, or connecting, pausing to reflect on the job is good for both you and the person you are helping.

# 3: Try to be objective

Mindfulness is not just about being fully present. It also requires being non-judgmental and supportive. For example, we have both been disappointed by mentees who show up late for meetings; annoyed by those who over promise but under-deliver; and even sad when mentees have told us that they were hoping for a different mentor or experience.

However, rather than react reflexively, we try to distance ourselves from our emotions and instead observe them as an onlooker. We focus on remaining objective during the interaction. Just as clinicians work to prevent emotions in the moment from getting in the way of patient care, mindful mentors resist allowing emotions to influence their real-time interactions with mentees. Sometimes mentees really do repeatedly drop the ball and thoughtful course corrections don’t work; in those cases, more drastic measures may be called for. But often a mentee is late for a good reason, one they can’t control – like staying to hold a family meeting or to be at a dying patient’s bedside. Or a mentee fails to deliver because they simply have way too much on their plate — after all, there are just 24 hours in a day. Or maybe the mentee realizes that you aren’t the best match — and that’s okay. The point is, mindfully withholding immediately judgement and emotions is best for all involved.

#4: Put yourself in their shoes

In the classic leadership book The One Minute Manager, Blanchard and Spencer use a symbol — the face of a digital watch — to remind us to regularly look into the faces of the people sitting across from us and realize they are important. This is as true for mentors guiding mentees as it is for clinicians treating patients.

We have consciously worked on being fully engaged when helping others in the clinical and mentoring domains. As clinicians we do this by performing a grounding exercise before seeing a patient. Before entering the patient’s hospital room, for example, we pause to use the hand sanitizer outside each door. The twist? We use the moment to be mindful — to consider that this could be our family member’s room, and we are the onlookers rather than the doctor. Or what if we were the patient and our doctor strolled in? As we pay attention to the feel of the alcohol gel, its odor, and the cold sensation as it evaporates, we envision what will happen once we step in the room and how we should comport ourselves. This 10-second ritual before seeing a patient is our personal reminder of the duty we have to those who depend on us for their medical care — a reminder that this is someone’s mother, father, sibling, child. And it helps us focus before we see each patient, every time.

Likewise, before meetings with mentees (especially ones where difficult feedback or conversations may happen), we consciously try to put ourselves in their shoes before and during the conversation. This has made us more empathetic and compassionate in our roles as mentors. Making it as a junior physician or budding academician is hard. Established leaders lose sight of this and forget the struggles that their mentees face. By putting ourselves in the role of the mentees — and doing so purposefully several times during our interactions — we have learned to take the edge off the sometimes difficult advice we provide. When critiquing our student’s suboptimal case presentation, for example, we think to ourselves “they are doing the best they can” and provide feedback accordingly. In fact, the realization that most of us are doing the best we can given the circumstances reminds us that criticism without kindness can seem cruel to the recipient.

Being a mindful clinician or mentor is not easy. It takes time, patience, and perseverance. But it also takes practice. Start by being fully present — all in, if you will — during interactions with your mentees, as we see this practice as foundational. This first step can help unlock the others. Your patients would expect nothing else. So why should your mentees?

The Words and Phrases to Use — and to Avoid — When Talking to Customers

CSA Images/Getty Images

CSA Images/Getty ImagesThe key to any successful relationship is effective communication. In the business world, this means trying to understand what consumers and clients are saying, and responding to them in ways that reflect that understanding. For the most part, however, the way businesses have used language to persuade, satisfy, or rectify has been more art than science.

The retail world in particular abounds with catch-phrases, habits, and commonly copied templates: “Say it with a smile.” “Never say no.” “Sorry is a magic word.” “A person’s own name is the sweetest sound in any language.” But do these and other long-held tips about how to speak to customers really work?

Studying the effectiveness of the words businesses use to talk to customers is tricky, but the rise of digital communications, social media, and big data is producing massive amounts of text that researchers can analyze and interpret using sophisticated new techniques. By combining natural language processing, computational linguistics, and psychology experiments, we can now uncover the true importance of subtle variations in how customers talk to front-line employees, and how customers respond to the words chosen by those employees. This allows us to understand the ways people communicate in business settings with growing precision, and what language is most effective.

It is now clear, according to our research and that of others, that some of the time-honored truths of customer service interactions fail to hold up to scientific scrutiny. You can, for example, say “sorry” to a customer too many times. Even if you’re a member of the company’s team, it is often better to say “I” than “we.” And not every piece of communication needs to be perfect; sometimes, a few mistakes produces a better result than flawlessness.

Here is the latest on the fast-growing, insightful, and sometimes surprising new world of business language research.

Be Human…

The body of research analyzing language use among customers, and between employees and customers, suggests a personal touch is indeed crucial. This is particularly important given the growing frequency of conversations that happen via technology (the phone, email, text, or chats) rather than in-person. Here are a few tips based on the latest research:

Speak as an individual, not part of a team. While companies and employees believe they should refer to themselves as “we” when talking to customers, and actually do so in practice, our research shows this practice is less than ideal. In a series of controlled studies, company representatives who referred to themselves in the singular voice (e.g., “I”, “me”, or “my”) were perceived to be acting and feeling more on behalf of customers than those who adopted less personal plural pronouns (“we” or “our”). For instance, saying “How can I help you?” outperforms “How can we help you?”). For one company, an analysis of over a thousand email interactions with customers found that switching to first person singular pronouns could lead to a potential sales increase of over 7%.

Share the same words. People who mimic the language of the person they’re interacting with are trusted and liked more, whether this mimicry entails how they talk (pronouns like “I” or “we,” articles like “it” or “a”) or what they talk about (nouns like “car,” verbs like “drive,” adjectives like “fast”). For example, in response to a customer inquiry such as “Will my shipment arrive soon?” an agent would be better off saying “Yes, your shipment will arrive tomorrow,” rather than “Yes, it’s being delivered tomorrow.” Employees’ linguistic mimicry creates affiliation with the customer, and research in progress by Francisco Villarroel Ordenes, Dhruv Grewal, Lauren Grewal, and Panagiotis Sarantopoulos has linked mimicry to customer satisfaction. Rapport can also be created by asking employees to imagine the customer as similar to themselves (e.g., shared background, personal, or business interests), even when they may be thousands of miles apart.

First, relate. Researchers performing automated text analysis of hundreds of airline customer service transcripts found that, consistent with consumer self-reports in prior research, expressing empathy and caring through “relational” words was critical, at least in the first (opening) part of service interactions. Relational words are verbs and adverbs that demonstrate concern (e.g., please, thank you, sorry) as well as signal agreement (e.g., yes, uh huh, okay). While this finding may not seem surprising, what may be for some is that front-line employees shouldn’t necessarily offer a caring, empathetic touch over the entirety of the interaction.

… And Then Take Charge

While using words that establish a more personal rapport with customers is important out of the gate, a new trove of research suggests that the assumed importance of front-line “empathizers” may be limited. More sophisticated analysis of the language of customer interactions suggests that once they’ve shown they’re listening, front-line employees should quickly shift gears towards language that signals a more assertive, “take charge” attitude.

Move from relating to solving. The same research that examined airline check-in service transcripts found that after an initial period in which the employee demonstrates their empathy for the customer’s needs, hearing employees say “sorry” and other “relating” words had little effect on customer satisfaction. Instead, automated text analysis revealed that customers wanted employees to linguistically “take charge” of the conversation. Specifically, this research suggested a shift to “solving” verbs (e.g., get, go call, do, put, need, permit, allow, resolve) as the interaction unfolds was an important predictor of customer satisfaction. Similar results were found by Ordenes and his colleagues in their in-progress research that analyzed a major consumer product company’s online chat-based interactions with customers. Automated text analysis of these conversations found that customer satisfaction is higher when front-line employees dynamically shift from deferent words (e.g., afraid, mistake, pity) to more dominant language (e.g., must, confirm, action).

Be specific. Analysis of the language used in telephone and email customer service interactions at two major retailers found that after the introductory phase of a conversation, when agents must show they are listening, customers see employees as more helpful when they use more concrete language. For example, for a clothing retailer, “white turtleneck” is more concrete than “shirt,” and “sneakers” is more concrete than “shoes.” Lab experiments currently underway by one of us (Grant Packard) and Jonah Berger suggest that using more concrete language signals to the customer that the agent is psychologically “closer” to the customer’s personal needs. For one of the retailers, a field analysis of over 1,000 email service interactions found that moving from “average” concreteness to one standard deviation above the average (roughly speaking, at about the 68th percentile of linguistic “concreteness”) was linked to a 4% lift in customer purchases after talking to the employee.

Don’t beat around the bush. Analysis of the language used in consumer and expert product reviews — plus lab studies — suggest that subtle variations in the words used to endorse a product or action can have substantial effects. For example, people are more persuasive when they use words that explicitly endorse the product to the customer (“I suggest trying this one” or “I recommend this album”) rather than language that implicitly does so by sharing the speaker’s personal attitude (“I like this one” or “I love this album”) towards a product or service. This is because explicit endorsements signal both confidence and expertise on the part of the recommender, a perception that could be particularly important in personal selling contexts.

As more and more consumer-firm conversation moves online or to other text-based media, the importance of utilizing language properly is greater than ever. However, firms are frequently teaching their employees to use language that doesn’t stand up to scientific scrutiny. Fortunately, new research using automated text analysis and methods from linguistic psychology offer some simple, actionable, and nearly cost-free solutions to improve the speaking terms by which companies engage their customers. What’s more, advances in natural language processing and machine learning seem primed to help researchers and managers uncover even deeper insights on how words really work for businesses.

The Chairman of Nokia on Ensuring Every Employee Has a Basic Understanding of Machine Learning — Including Him

ANTTI AIMO KOIVISTO/Getty Images

ANTTI AIMO KOIVISTO/Getty ImagesI’ve long been both paranoid and optimistic about the promise and potential of artificial intelligence to disrupt — well, almost everything. Last year, I was struck by how fast machine learning was developing and I was concerned that both Nokia and I had been a little slow on the uptake. What could I do to educate myself and help the company along?

As chairman of Nokia, I was fortunate to be able to worm my way onto the calendars of several of the world’s top AI researchers. But I only understood bits and pieces of what they told me, and I became frustrated when some of my discussion partners seemed more intent on showing off their own advanced understanding of the topic than truly wanting me to get a handle on “how does it really work.”

I spent some time complaining. Then I realized that as a long-time CEO and Chairman, I had fallen into the trap of being defined by my role: I had grown accustomed to having things explained to me. Instead of trying to figure out the nuts and bolts of a seemingly complicated technology, I had gotten used to someone else doing the heavy lifting.

Why not study machine learning myself and then explain what I learned to others who were struggling with the same questions? That might help them and raise the profile of machine learning in Nokia at the same time.

Going back to school

After a quick internet search, I found Andrew Ng’s courses on Coursera, an online learning platform. Andrew turned out to be a great teacher who genuinely wants people to learn. I had a lot of fun getting reacquainted with programming after a break of nearly 20 years.

Insight Center

Scaling Your Team’s Data Skills

Sponsored by Splunk

Help your employees be more data-savvy.

Once I completed the first course on machine learning, I continued with two specialized follow-up courses on Deep Learning and another course focusing on Convolutional Neural Networks, which are most commonly applied to analyzing visual imagery. As I became more familiar with the topic, I also spent some time reading research papers and articles on machine learning architectures and algorithms not covered by Andrew’s courses. After three months and six courses, I had covered both the simple algorithms as well as many of the more complicated architectures, doing one project with each to gain a hands-on understanding.

Then I dug into the most difficult part: how to explain the essence of machine learning in the simplest possible way, but without dumbing it down. I created the presentation I wish someone had given me. (The presentation is on YouTube, where, so far, it’s been watched by nearly 45,000 people. I’ve also given it to, among others, the full Finnish cabinet, many of the commissioners of the European Union, a group of United Nations ambassadors, and 200 teenage schoolgirls to get them interested in science. Many companies have made watching my introduction to machine learning mandatory for their management.)

Thousands of Nokia employees have seen my presentation and been inspired by it. Many of our R&D folks have come to me to confess that they were a bit ashamed that their chairman was coding machine-learning systems while they had not even started. But, they said, now they were devoting their own free time to studying machine learning and were working on the first Nokia projects as well. Music to my ears.

But that was just the first step.

The Five Steps to AI Competence

I wanted to build a way to promote a wider understanding of machine learning — not just for engineers, but for everyone at Nokia. To that end, the most valuable part of my experience has been creating a template for “The Five Steps to AI Competence.” I hope leaders across all industries can learn from these steps as they seek insights about using machine learning in their businesses:

Make everyone learn their AI ABC’s. We plan to make familiarity with the fundamentals of machine learning a mandatory process, like knowing the company’s code of conduct. We’ll create an online test. Every employee will have to study that much machine learning.

The point is not just that each individual will discover that they can understand machine learning. There’s a deeper meaning: that learning is something we need to be doing throughout our lives and that we can understand some pretty complicated stuff even if we don’t believe that at first. If we can surprise our people with their ability to learn new things, that can be very positive — for them and the company.

Create a competent pool of experts. When a business leader or anyone, for that matter, comes up with an idea — “Hey, we could save a ton of money if we did this” or “We could make this product more competitive if we could teach a machine learning system to help” — we’ll have a pool of experts to evaluate the idea and decide, “Yes, we can do it” or “Let’s try it and see” or “No way.” This could be an in-house competence center or it could even be outsourced to a third-party AI company.

These data scientists would parachute into a business unit’s generic R&D team to show them how to do what’s necessary. With every project, they’ll leave behind people who now have hands-on experience and are more knowledgeable about machine learning. They’ll spread their learning and at the same time, when they return to the centralized competence center, they can share their experience about what works on the ground.

By the way, it’s important to centralize because in today’s tight talent market, it’s much easier to recruit top talent in machine learning if they know they will be working with similarly talented colleagues.

Pair robust IT systems and data strategy. We’ll need to build IT systems that can combine any subset of data the company has access to with any other subset to amass the exact data necessary to implement a particular machine-learning system. (This may be complicated by different countries’ privacy legislation.) Setting up a data lake is pure IT work. The strategy half of the equation involves anticipating and forecasting our future data needs. In three or five years, there will be aspects of our business in which our competitiveness will be largely defined by the machine learning systems we will put in place. We’ll need to look forward to understand and acquire the data we’ll need at that time to train the systems which will be critical to our competitiveness.

Implement machine learning internally. There are numerous jobs that can be done better and faster if you augment the people working on those tasks with machine learning. For that, we’ll need to change people’s behavior so that they look at everything around them as an opportunity to automate.

Integrate machine learning into products and services. We must constantly analyze ways to leverage machine-learning to improve competitiveness with our customers.

Because these five steps are all equally important parts of the AI future, they must be implemented simultaneously. While we start teaching our employees the basics of machine learning, we can start building the IT infrastructure, searching for talent and, in partnership with our existing IT teams, work to add machine-learning competencies into our products and services. By raising the level of all the different elements of our machine-learning abilities at once, each element can connect with and enhance every part it touches. Instead of one part holding others back, everyone rolls forward together, sharing lessons, sparking new ideas and gathering momentum.

I often describe myself as an entrepreneur. When you have an entrepreneurial mindset, everything is your responsibility. You truly care and your actions communicate that loud and clear.

I could have just supported the Nokia CEO and management team in talking about the need to kick-start a fast catch-up in machine learning. But talk is cheap. Taking actions that people can see and are motivated to copy is better than any high-toned speech. The fact that the chairman of a global company went back to school and to learn a critical piece of technology was novel enough to get people’s attention and encourage them to act on their own.

I hope it’s just the beginning.

How to Cope with Secondhand Stress

Mike Stobe/Getty Images

Mike Stobe/Getty ImagesIt’s a well-known phenomenon: emotions are contagious. If you work with people who are happy and optimistic, you’re more likely to feel the same. The flipside is true, too; if your colleagues are constantly stressed out, you’re more likely to suffer. How do you avoid secondhand stress? Can you distance yourself from your coworkers’ emotions without ostracizing them? And should you try to improve their wellbeing?

What the Experts Say

First, the bad news: secondhand stress is nearly inescapable. “We live in a hyper-connected world, which means we are more at risk for negative social contagion than at any point in history,” says Shawn Achor, lecturer, researcher, and author of The Happiness Advantage. “Secondhand stress comes from verbal, nonverbal, and written communication, which means we can pick it up even via cellphone.” But the good news is that we are not helpless, says Susan David, a founder of the Harvard/McLean Institute of Coaching and author of Emotional Agility. “There are many specific skills you can learn, behaviors you can practice, and tiny tweaks you can make in your environment that will be helpful in dealing with secondhand stress,” she says. Here are some strategies.

Identify the source

Before you wage war on secondhand stress, you must acknowledge that some stress can be good, says David. “You don’t get to have to have a meaningful career, raise a family, lead, or make changes in an organization without some level of stress.” If certain members of your team are strained, David recommends, “trying to understand what’s really going on” rather than “stressing about their stress.” Ask them to describe what they’re experiencing. “Find out whether they’re anxious about [their workload] being more than they can cope with or whether it’s more of a nonspecific discomfort.” David says that, “When people accurately label their emotions, they’re more likely to identify the source of their stress and do something about it.”

Offer assistance

It’s understandable why talking to your overstretched, stressed-out colleague might make you feel nervous. But Achor says you can keep your own emotions in check by being empathetic. “By expressing compassion for this person’s concern and then engaging them in positive conversation — either to generate a solution to their problem or shift their focus away from it — we often positively influence them instead of solely letting them negatively affect us.” David agrees that the power to influence goes both ways. “You and everyone else are doing the best you can with who you are, what you’ve got, and the resources you’ve been given.” So, be helpful, she advises. Ask your colleague, “Is there anything I can do to help you move that project forward? Is there a conversation we should have that might lead to a more constructive outcome?”

Take breaks from certain colleagues

Achor admits that it’s not always easy to be compassionate toward your office’s Negative Nancy. If you feel the person is starting to take a toll on you, you can “take strategic retreats” and limit your contact with anxiety-inducing colleagues. “Quarantine them” from work life as much as possible “until you can strengthen yourself,” Achor says. David concurs. “If your conversations with certain colleagues tend to “center on stress or negativity about the organization,” you may need to step back temporarily. “Recognize which interactions are not helpful,” she says.

Cultivate optimism

Another strategy for coping with secondhand stress is to “surround yourself with positive people,” says Achor. Positive emotions can be just as contagious as negative ones. Make an effort to promote optimism in the ranks, too. “Most people make the mistake of trying to fix the most stressed-out, negative person in the office.” Instead, he recommends acting as a role model by exuding positivity for “the people in the middle who could be tipped positive or negative.” Doing so “tilts the social script” toward optimism and increases “the number of positive forces” in the workplace. Your goal, says David, is to “create an environment where people who are on the border” feel confident about the organization. You don’t want a situation where “one individual’s stress is the only voice in the room.”

Remember the big picture

Even if your job is manageable it can quickly become a source of anxiety “if everyone else around you is stressed” and vocal about it, according to David. “People often go on about their ‘have-to’ goals — as in ‘I have to go to this meeting.’ Or ‘I have to be on this client call,’” she says. Grousing about a large and looming to-do list is seen as a badge of honor, and the complaining often catches on. But, she says, it’s dangerous. Categorizing your workload this way “creates a prison around yourself.” She recommends turning your “have-to” goals into “want-to” goals. For instance, “‘I value collaboration, and I want to attend this meeting because it will facilitate that.’ Or, ‘I value generating a high-quality product for my client, so I want to be present on this call.’ It’s powerful realignment for individuals who are affected by secondhand stress,” she says. Think about “your career objectives” and “connect your obligations with something positive.”

Take care of yourself (and help others do the same)

One of the best ways to ward off stress — be it second- or firsthand — is to take impeccable care of your health. Eating well and getting plenty of exercise and sleep are critical to keeping stress at bay. So, too, is practicing gratitude, says Achor. “Thinking of things you are grateful for sounds trite, but it gives you a storehouse of positives to help neutralize and counterbalance any negatives you are inevitably going to experience,” says Achor. Importantly, he adds, you must share what you have learned. He says he’s often surprised by the number of leaders who tell him “that they journal positive experiences, or do yoga, or meditate, and yet they never mention it to the very people on their teams they are trying to motivate.” This is a travesty, he says. “If you have a positive habit and it works for you, tell everyone.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Show compassion to your stressed-out colleagues. Rather than getting agitated, ask how you can help.

Surround yourself with positive people to benefit from their secondhand confidence, optimism, and happiness.

Take strategic retreats from negative colleagues when necessary.

Don’t:

Try to fix the most stressed-out person your team; instead, model optimism and positivity.

Get bogged down listening to others’ moan about their stressful “have-to” lists; connect your work to your values and remember the big picture.

Be secretive about your positive habits. Take good care of yourself and share your strategies.

Case Study #1: Support your team and foster positivity within the ranks

Gloria Larson, the president of Bentley College, says that she has always been a “ridiculously optimistic” person. “For me the glass is 90% full,” she says. “But, of course, I feel stressed when things are challenging. And I’m not immune to the effects of other people’s stress, too.”

Years ago, when she was an attorney at Foley Hoag in Boston, Gloria volunteered to chair a committee in charge of building the Massachusetts Convention Center, an $800 million construction project along the waterfront. Early in the project, she held a press conference claiming that the project would be “on time and on budget.”

Then, the project ran into problems, including large cost overruns. “It was ugly, and it played out on the front pages of the Boston Globe and the Boston Herald,” says Gloria. “I looked around [at the board and the other senior leaders], and I could see that the team was stressed.”