Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 782

November 6, 2018

Avoiding Miscommunication in a Digital World

Nick Morgan, a communications expert and speaking coach, says that while email, texting, and Slack might seem like they make communication easier, they actually make things less efficient. When we are bombarded with too many messages a day, he argues, humans are likely to fill in the gaps with negative information or assume the worst about the intent of a coworker’s email. He offers up a few tips and tricks for how we can bring the benefits of face-to-face communication back into the digital workplace. Morgan is the author of the book, Can You Hear Me?: How to Connect with People in a Virtual World.

Ego Is the Enemy of Good Leadership

Francesco Carta fotografo/Getty Images

Francesco Carta fotografo/Getty ImagesOn his first day as CEO of the Carlsberg Group, a global brewery and beverage company, Cees ‘t Hart was given a key card by his assistant. The card locked out all the other floors for the elevator so that he could go directly to his corner office on the 20th floor. And with its picture windows, his office offered a stunning view of Copenhagen. These were the perks of his new position, ones that spoke to his power and importance within the company.

Cees spent the next two months acclimating to his new responsibilities. But during those two months, he noticed that he saw very few people throughout the day. Since the elevator didn’t stop at other floors and only a select group of executives worked on the 20th floor, he rarely interacted with other Carlsberg employees. Cees decided to switch from his corner office on the 20th floor to an empty desk in an open-floor plan on a lower floor.

When asked about the changes, Cees explained, “If I don’t meet people, I won’t get to know what they think. And if I don’t have a finger on the pulse of the organization, I can’t lead effectively.”

Further Reading

The Mind of the Leader

Leadership & Managing People Book

Harvard Business Review

30.00

Add to Cart

Save

Share

This story is a good example of how one leader actively worked to avoid the risk of insularity that comes with holding senior positions. And this risk is a real problem for senior leaders. In short, the higher leaders rise in the ranks, the more they are at risk of getting an inflated ego. And the bigger their ego grows, the more they are at risk of ending up in an insulated bubble, losing touch with their colleagues, the culture, and ultimately their clients. Let’s analyze this dynamic step by step.

As we rise in the ranks, we acquire more power. And with that, people are more likely to want to please us by listening more attentively, agreeing more, and laughing at our jokes. All of these tickle the ego. And when the ego is tickled, it grows. David Owen, the former British Foreign Secretary and a neurologist, and Jonathan Davidson, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, call this the “hubris syndrome,” which they define as a “disorder of the possession of power, particularly power which has been associated with overwhelming success, held for a period of years.”

An unchecked ego can warp our perspective or twist our values. In the words of Jennifer Woo, CEO and chair of The Lane Crawford Joyce Group, Asia’s largest luxury retailer, “Managing our ego’s craving for fortune, fame, and influence is the prime responsibility of any leader.” When we’re caught in the grip of the ego’s craving for more power, we lose control. Ego makes us susceptible to manipulation; it narrows our field of vision; and it corrupts our behavior, often causing us to act against our values.

Our ego is like a target we carry with us. And like any target, the bigger it is, the more vulnerable it is to being hit. In this way, an inflated ego makes it easier for others to take advantage of us. Because our ego craves positive attention, it can make us susceptible to manipulation. It makes us predictable. When people know this, they can play to our ego. When we’re a victim of our own need to be seen as great, we end up being led into making decisions that may be detrimental to ourselves, our people, and our organization.

An inflated ego also corrupts our behavior. When we believe we’re the sole architects of our success, we tend to be ruder, more selfish, and more likely to interrupt others. This is especially true in the face of setbacks and criticism. In this way, an inflated ego prevents us from learning from our mistakes and creates a defensive wall that makes it difficult to appreciate the rich lessons we glean from failure.

Finally, an inflated ego narrows our vision. The ego always looks for information that confirms what it wants to believe. Basically, a big ego makes us have a strong confirmation bias. Because of this, we lose perspective and end up in a leadership bubble where we only see and hear what we want to. As a result, we lose touch with the people we lead, the culture we are a part of, and ultimately our clients and stakeholders.

Breaking free of an overly protective or inflated ego and avoiding the leadership bubble is an important and challenging job. It requires selflessness, reflection, and courage. Here are a few tips that will help you:

Consider the perks and privileges you are being offered in your role. Some of them enable you to do your job effectively. That’s great. But some of them are simply perks to promote your status and power and ultimately ego. Consider which of your privileges you can let go of. It could be the reserved parking spot or, like in Cees ‘t Hart’s case, a special pass for the elevator.

Support, develop, and work with people who won’t feed your ego. Hire smart people with the confidence to speak up.

Humility and gratitude are cornerstones of selflessness. Make a habit of taking a moment at the end of each day to reflect on all the people that were part of making you successful on that day. This helps you develop a natural sense of humility, by seeing how you are not the only cause of your success. And end the reflection by actively sending a message of gratitude to those people.

The inflated ego that comes with success — the bigger salary, the nicer office, the easy laughs — often makes us feel as if we’ve found the eternal answer to being a leader. But the reality is, we haven’t. Leadership is about people, and people change every day. If we believe we’ve found the universal key to leading people, we’ve just lost it. If we let our ego determine what we see, what we hear, and what we believe, we’ve let our past success damage our future success.

U.S. Health Plans Can Save Billions by Helping Patients Navigate the System

Shana Novak/Getty Images

Shana Novak/Getty ImagesMost people at one time or another have struggled to navigate the complexities of the U.S. health care system. Many have received unpleasant surprises, such as a medical bill they expected to be covered by their health insurance or an unexpectedly expensive bill for a simple service. This type of confusion results in a lot of administrative work, including avoidable calls to customer service centers or time spent helping people find lower-cost options for services. It is costing employers and health plans billions of dollars each year.

Recognizing this exorbitant cost, Accenture developed a literacy index to evaluate how well consumers can obtain, understand, and navigate information and services. We used this index to assess how health care literacy affected the performance of nine consumer experience touchpoints. We then calculated the correlating impact to administrative costs. From this, we identified strategies in which health plans could save themselves billions of dollars — by simplifying the “user experience” of a system that was not designed with the preferences of the consumer in mind.

Our analysis found the health care system is so complex that more than half (52%) of consumers are unable to navigate it on their own, triggering avoidable customer service calls and more costly care. Consumers with low health system literacy are three times more likely to contact customer service. Our estimates found health insurers and employers spend $26 more on administration fees for every consumer with low health system literacy. This translates into a total cost of $4.82 billion, which would be even higher if accounting for medical cost.

Insight Center

The Future of Health Care

Sponsored by Medtronic

Creating better outcomes at reduced cost.

We found that consumers with low literacy struggle to make informed decisions about everything from the health plan types they choose and the premiums they pay to the doctors they see and the procedures they have done. It is worth noting this issue has nothing to do with education level: Roughly half (48%) of low-literacy consumers are college educated and nearly all (97%) have at least a high school diploma.

Difficulty in making informed decisions impacts consumers’ ability to get the medical care they need. This is especially detrimental for the one in four (26%) consumers who have both low understanding and the highest need for health care interventions, such as individuals who are facing chronic or serious conditions. While our study assessed the impact of low literacy on administrative expenses, two decades of research has documented the impact of literacy on the overall health economy — some estimate the cost to add up to as much as $238 billion, or 17%, of all U.S. health expenditures.

Education has a role to play in reducing costs for health insurers, but it alone will not eliminate the problem. To ease their cost burden, health plans should instead aim to simplify the user experience. Our research points to a few strategies that health plans can implement a new model of consumer service and engagement. This can be achieved by harnessing digital channels to make the user experience easier, incentivizing progress driven by other stakeholders in the system, and shifting the complexity burden off consumers.

Harness digital channels to improve user experience. While systemic complexity won’t be eliminated in the short term, health plans can approach service differently to make navigating the health care system feel simpler and easier. Amazon and other digital retailers have done just that. Consumers can select one-click options to get their delivery within a specific timeframe, but are oblivious to the operational complexity that goes on behind the scenes to make it happen. In today’s increasingly technological world, consumers expect this type of simplicity and digital access across all industries that they interact with.

One example of a company in the health industry that is seeking to simplify the process is Oscar Health, a New York City-based insurance company serving six states and 250,000 members. While widely known for using digital, telemedicine, and concierge service to augment care, Oscar Health has also tackled operational complexity across core insurance functions, like claims processing, providing its 240,000 members with cost estimates for select medical services.

Incorporating intelligent technologies such as artificial intelligence to customer service initiatives can also help with delivering easy-to-follow programs and relevant products.

Incentivize progress. Another solution to cut through complexity is incentivizing health providers and consumers to work together in navigating health insurance options.

We know that providers influence where consumers go for health services. A recent NBER study found that, when choosing between low- and high-cost care settings, referring physicians had far more influence over where consumers sought care than cost did. Employer plans — such as those offered by startup Centivo — are bucking this trend by incentivizing physicians and patients to work together to lower the cost of care.

Other programs focus on educating consumers on how to choose affordable care settings on their own. Programs provided by Vitals, for example, offer consumers cash-back rewards when they select a lower-cost service or procedure such as an MRI or mammogram. Incentives such as these are more likely to drive consumers to change their behaviors, and in the process will educate them about how to make better and cost-efficient care choices.

Shift the complexity burden off consumers. Health plans also need to deploy new product concepts that take us closer to the goal of simplification and orchestrate service options to reach low literacy consumers on their terms.

For example, organizations can offer simple, per-visit copayments instead of complex deductible and coinsurance plans. That is what Minneapolis-based startup Bind Benefits is doing by offering employers on-demand plan options with no deductibles. The idea is to offer simple, straightforward pricing rather than complex plan structures so consumers can easily engage and know the price of their services at the time of consumption.

Ultimately, the only way to eliminate systemic complexity in health care is by actually making health care simpler. Rather than forcing consumers to battle the complexities, the health care system must design user experiences to align seamlessly with the needs, behaviors, and preferences of the people it serves.

Competing in the Huge Digital Economies of China and India

Jeff Greenberg/Getty Images

Jeff Greenberg/Getty ImagesThe global digital economy crossed an important milestone recently: the number of internet users in two countries — China, with just over 800 million users, and India, with 500 million users – surpassed the aggregate number of internet users across 37 OECD countries combined. In both countries, users spend more time on the internet than the worldwide average of 5.9 hours per day. They also have room to grow; China has just under 60% of its population online, while India, with one of the lowest rates of internet penetration in the world, has under 25% of its population online.

While it’s tempting to group China and India together as a block of emerging digital markets, they offer several important distinctions, especially for international entities and countries looking to invest. In our Digital Evolution Index (DEI), we place them in the “digital south” which means the full deployment and adoption of online systems is still in development. Our DEI research classifies both China and India as “Break Out” countries, which means they are experiencing strong digital growth. China has 783 million smartphone users and, as reported by the Cyberspace Administration of China, had 469 million registered on a mobile payment platform in January 2017. It is also the world’s largest market for e-commerce. And India is on track to become the youngest country in the world by 2020 and its digital economy is expected to balloon from $413 billion today to $1 trillion dollars by 2025.

Both China and India present barriers to entry for foreign players. The most obvious distinction between the two markets is that China is mostly closed to international players because of state restrictions, while India is, technically, open for business. Top U.S. companies are investing heavily in India — as are Chinese companies, such as Alibaba and Tencent. However, India presents barriers that are less visible. Consider two examples:

Languages: Language poses a high barrier to entry or growth for any company. Less than 100 million out of India’s 700 million literate population can read or write English. There are 32 different languages with a million-plus speakers each across India, whereas in China, Mandarin is understood by the majority. In India, 90% of the country’s registered publications do not have a website because of language barriers and 95% of video consumption is in local languages. It is essential to crack at least five Indian languages to truly break into this market.

Protectionist policies: While China’s protectionist policies are transparent, India’s protectionist agenda is in the form of regulations and red tape. For example, a recently proposed Indian government policy on e-commerce and a similar order from the country’s central bank seeks to prohibit data on Indian e-commerce consumers from being stored outside India. Many international players view this as favoring homegrown digital companies and a case of India borrowing from China’s playbook, that mandates local storage of Chinese user data considered “sensitive”.

The few international players active in China have scaled the entry barriers through adaptive (and sometimes risky, complex, or controversial) strategies, while others that have been blocked – e.g. Google and Facebook – keep experimenting with ways to comply with the state restrictions and invite fresh controversies. In parallel, companies will need to tailor their approaches to fully crack India, but in different ways. Building on our example above, in response to the language barrier, Google has invested in its Translate app and in its AI-enabled multi-local language publishing platform while Amazon plans to launch in multiple local languages in India. Even for these giants, there is a long way to go.

Both China and India have governments deeply engaged in orchestrating the digital economy and in citizens’ data. It is well-known that China’s government has ambitious objectives for the country’s digital future. According to China scholar Adam Segal’s analysis, the Chinese President Xi Jinping “aims to build an ‘impregnable’ cyber-defense system, give itself a greater voice in Internet governance, foster more world-class companies, and lead the globe in advanced technologies.” Among its other ambitions, a July 2017 State Council document aims to position China as the world’s AI leader by 2025.

In the context of this agenda, the Chinese government is assembling a comprehensive database on its own citizens with help from Chinese technology companies that routinely synchronize with the government. The data will establish a social credit system expected to be both mandatory by 2020. Every Chinese citizen’s “social credit score”, drawing upon public and private data sources can determine what services – from no-deposit apartment rentals to booking airline tickets to dating to government services — are accessible to the citizen. The private sector, companies such as Alibaba – e.g. Sesame Credit, run by the Ant Financial, an Alibaba affiliate. — and Tencent, through its popular messaging platform, WeChat, have become enormous repositories of user data, with which they can better design and target new services, discern key user attributes, such as credit-worthiness, and train algorithms. They also help the government with necessary data and algorithms. This public-private collaboration not only helps serve the state objectives of citizen surveillance and preserve social order, but also produces user data that improves China’s AI capabilities.

Meanwhile, India’s government also has ambitious objectives for the country’s digital economy. Relative to its Chinese counterparts, India’s authorities have been focused on the fundamentals — on low-cost access to digital tools and on creating an open and inter-operable infrastructure. The country has embarked on a broad Digital India initiative that encompasses everything from broadband “highways” to e-governance to digital literacy. There are also plans to establish 100 “smart cities” across India in collaboration with public agencies and private companies.

Like China, India, too, has a citizens’ database. The aspirations for such a database were to establish a universally accepted form of identification to promote inclusive access to a variety of services in a country where many are excluded because of a lack of key documentation. As the core visionary behind this initiative, technology pioneer and Infosys co-founder, Nandan Nilekani, writes, the essential idea was to “empower users with the technical and legal tools required to take back control of their data.”

Nilekani led the initiative that produced such a system, Aadhaar, which has enrolled 1.2 billion citizens. Aadhaar has become the foundation for an “India stack”, the world’s largest API that allows any enterprise, private or public, to build services and linking them to each individual’s unique identity.

While each country has chosen a different path, both markets are being shaped by governments defining a framework and working with the private sector to populate it. Of course, state-organized citizen databases raise plenty of concerns. China’s social credit system raises worries about “Orwellian” mass surveillance. In addition, the growing use of facial recognition technologies across China adds to worries about privacy and government over-reach.

In India, Aadhaar had increasingly become mandatory for privately offered services, such as mobile communications, banking and airline bookings as well as government programs, triggering concerns from consumer privacy and advocacy groups. The Aadhaar database itself has not proven to be secure and there were worries about both commercial abuse of data and government surveillance of citizens. As in China, India has also entertained proposals to add facial recognition to the database. The mandatory aspect of Aadhaar was re-visited after being legally challenged and the country’s Supreme Court has ruled that while the ID system is constitutionally valid and is required as proof-of-identity for government programs, it cannot be mandated for private services, making it harder for companies to authenticate their customers.

Companies looking to enter either of these markets will need to be prepared to navigate a digital landscape being actively shaped by the government. They will also have to contend with some difficult privacy issues; in China the rules of play on these issues are clearer, while in India the rules can change with political turnover, as well as the outcomes of legal challenges and citizen advocacy.

Both China and India are key contributors to the world’s growing middle class. Currently, China is ahead on the major economic metrics: to add as much to its GDP as China will in 2018, India would need to grow by 40%. But there are other measures that suggest that India might have a chance to narrow the gap. India’s middle class (defined as $11 – $110 a day in 2011 purchasing power parity terms) is expected to exceed that of China’s by 2030, according to the OECD and Brookings. Simultaneously, India’s high growth rate of 7.7% in the first quarter of 2018, continues to maintain its position as the world’s fastest-growing large economy. Some India-enthusiasts argue that its demographic advantage and democratic political system will prove beneficial over the long-term in catching-up with state-controlled China.

China is ranked 36th and India 53rd out of the 60 countries ranked by our DEI. In light of the potential narrowing of the broader economic gaps, it makes sense to ask if the gap between the digital economies of the two countries might narrow. How long will it take for India to get to China’s current level of digital evolution? What key drivers might help accelerate the journey? Could India plausibly narrow the gap? These questions are important for companies that would rather pursue opportunities in India, rather than contend with the high barriers in China, but are concerned about how far behind India is relative to China.

Using our DEI model, there are three possible catch-up scenarios:

First, if India were to pick up China’s momentum, it would reach China’s current level of digital evolution by 2029.

Second, if India could achieve 3% growth annually across several drivers, it could achieve China’s current level of digital momentum by 2022; these drivers are: physical infrastructure, government facilitation of the ICT sector, digital access, use of digital money and payments, national investment in R&D, gender digital inclusion, digital footprint of business, mobile internet gap.

Third, if India could accomplish the following combination of growth rates, it could reach China’s current state of digital evolution by 2024.

18% annual growth in Gender Digital Inclusion

3% annual growth in Physical Infrastructure

3% annual growth in national investment in R&D

1% growth in Digital Access Availability

This analysis suggests that narrowing the digital gap is within India’s reach. If international technology players and investors were to consider where they might intervene in India’s digital economy and provide leverage to the country’s policy objectives, they can participate in India’s digital economy while helping it accelerate and narrow the gap with China, a perennial economic rival. If this happens, India’s economy could even catch up to China’s. It is important for businesses, innovators, and policymakers to be aware of this potential for convergence between the two great powers of the digital south just as much as they see the differences in order to make wise strategic choices for approaching the two most essential digital markets in the world.

Transforming Customer Experiences: Driving Performance and Profitability in the Service Sector - SPONSOR CONTENT FROM HBS EXECUTIVE EDUCATION

The service sector is a large and growing part of our economy. But a lot of service businesses are managed according to old ideas imported from more traditional industries, says Ryan Buell, UPS Foundation Associate Professor of Service Management at Harvard Business School (HBS).

In today’s rapidly changing service sector, a new set of frameworks is required to build a robust and competitive service business, says Buell.

“Service jobs have a reputation for not being great jobs—and in many cases, I think it’s a well-earned reputation. But it shouldn’t be that way,” says Buell. “Service is the business of people helping people, and when employees lack the capability, motivation, and license to perform, there’s no hope they’ll deliver excellent service to customers.”

Transforming Customer Experiences

Transforming Customer Experiences draws upon the latest research and insights to equip senior managers with a new toolkit for leading and managing a professional services firm or a customer service or sales team. As a participant in this program, you will work alongside some of HBS’s most renowned service management thought leaders. You will learn innovative methods for designing exceptional service offerings, creating a distinct and sustainable service model, and effectively managing employees and customers.

Learn more.

[image error]

Buell is faculty chair of the HBS Executive Education course Transforming Customer Experiences, which explores how service leaders can create distinctive and sustainable service organizations that “turn customers into raving fans and employees into dedicated stewards of the mission.”

The program is distinctive in developing a holistic curriculum that speaks to the challenges faced by modern service organizations, Buell says. Participants in the program learn the fundamentals of transforming customer experiences through cases from and interactive lectures by HBS faculty members.

For instance, one case, developed by Buell, focuses on the way IDEO uses human-centered design thinking as a systematic methodology to help create new products and services. The case explores this process through the example of Cineplanet, a leading movie cinema chain in Peru. The company hired IDEO to help them determine how to better align their operating model with the needs of their customers. “This case study may change the way you think about thinking,” says Buell.

The HBS program also includes workshops and one-on-one coaching sessions with faculty who are experts in their fields to help participants discover gaps in the design and execution of the service businesses they lead so they leave with road maps for how to transform and revitalize those businesses.

“Our goal each day is for participants to walk away with practical ideas that can be put to work in their own organizations to make an immediate impact on performance—for employees, customers, and owners alike,” says Buell.

Peer-to-peer learning is also a key part of the program, which assembles a learning community of exceptional service leaders from all around the world.

“My colleagues and I will certainly bring ideas to the table, but just as importantly, we’ll work to set the conditions for participants to leverage and benefit from each other’s experiences,” says Buell.

“At any given point, there will be someone in the room who has faced a challenge similar to another person’s. Getting those people to have a conversation about how they solved the challenge is incredibly valuable, and it doesn’t necessarily happen by itself. We’re very intentional about fostering those interactions.”

The program features workshops on service design and service execution, and those workshops are particularly valuable for companies that send cross-functional teams to the program—that is, when they send multiple people who understand the organization from different angles, says Buell. In this context and setting, teams have an opportunity to deeply understand and diagnose challenges that their organization faces, but they also leverage their cross-functional expertise to identify opportunities to improve their business. Also, having a shared experience allows teams to go back to their organization with a common language and a common set of tools and frameworks for addressing business challenges.

To learn more about Transforming Customer Experiences at Harvard Business School Executive Education, taught by Ryan Buell and other renowned faculty, visit the program website.

If Your Employees Aren’t Speaking Up, Blame Company Culture

PM Images/Getty Images

PM Images/Getty ImagesCompanies benefit when employees speak up. When employees feel comfortable candidly voicing their opinions, suggestions, or concerns, organizations become better at handling threats as well as opportunities.

But employees often remain silent with their opinions, concerns or ideas. There are generally two viewpoints on why: One is the personality perspective, which suggests that these employees inherently lack the disposition to stand up and speak out about critical issues, that they might be too introverted or shy to effectively articulate their views to the team. This perspective gives rise to solutions such as hiring employees who have proactive dispositions and are more inclined to speak truth to power.

By contrast, the situational perspective argues that employees fail to speak up because they feel their work environment is not conducive for it. They might fear suffering significant social costs by challenging their bosses. This perspective leads to solutions focused on how managers can create the right social norms that encourage employees to voice concerns without fear of sanctions.

These two perspectives aren’t mutually exclusive, but we wanted to test which one matters more: If personality is the primary predictor of speaking up, situational factors shouldn’t matter as much. This means that employees who are inherently disposed to speak up will be the ones who more frequently do so. By contrast, if the situation or environment is the primary driver of speaking up, then employee personality should be less important – employees would speak up, irrespective of their underlying dispositions, when the work environment encourages speaking up, and they would stay silent when the environment doesn’t.

In our research we collected survey data from a manufacturing plant in Malaysia in 2014. We surveyed 291 employees and their supervisors (from 35 teams overall). We asked employees how likely they were inherently disposed to seeking out opportunities in their environment (also known in psychology as their approach orientation); this was how we assessed whether employees had a personality inclined toward speaking up. We also asked them whether speaking up is expected as part of their everyday work, and whether it is encouraged and rewarded or punished; this was how we assessed the situational norms associated with their work environment. Each employee rated their approach orientation, as well as the expectations in their job, using validated measures. For each employee in the team, we asked their supervisor to rate the frequency of speaking up.

The firm was responsible for manufacturing and sales of soaps, detergents, and other home cleaning products, and employees often encountered situations where there was compelling need to speak up about issues around current work operations. For instance, employees could suggest novel approaches to stacking raw materials, improving equipment layouts, or enhancing coordination during shift changes. They could also call out problems such as faulty safety gear or violations of standard operating procedures on the shop floor.

When we analyzed the data, we found that both personality and environment had a significant effect on employee’s tendency to speak up with ideas or concerns. Employees with a high approach orientation, who tend to seek opportunities and take more risks, spoke up more often with ideas than those with a lower approach orientation. And employees who believed they were expected to suggest ideas spoke up more than those who didn’t feel it was part of their job.

But we found that strong environmental norms could override the influence of personality on employees’ willingness to speak up at work. Even if someone had a low approach orientation, they spoke up when they thought it was strongly expected of them at work. And if someone had a high approach orientation, they’d be less likely to speak up with concerns when they thought it was discouraged or punished. Our data supported the situational perspective better than the personality perspective.

This finding suggests that if you want employees to speak up, the work environment and the team’s social norms matter. Even people who are most inclined to raise ideas and suggestions may not do so if they fear being put down or penalized. On the flip side, encouraging and rewarding speaking up can help more people do so, even if their personality makes them more risk-averse.

We also found that the environment could influence how employees spoke up. Employees voiced their opinions in two different ways—by identifying areas for improvement at work, and by diagnosing potential threats to the organization and calling out undesirable behaviors that might compromise safety or operations. We found that when norms at work encouraged detection of potential threats or problems, employees spoke out more on issues such as safety violations or breaches of established work practices. But when such norms encouraged improvements and innovation, employees more often spoke up with novel ideas for redesigning work processes that promoted innovation on the shop floor.

This suggests that work norms can not only encourage all employees to speak up but also focus their voice on specific issues confronting the organization. Managers working in contexts where innovation is important would do well to create an environment that specifically encourages employees to come up with ideas that can offer new opportunities for success. On the other hand, managers working in contexts where reliability is critical would do well to specifically create an environment where employees are focused on forecasting and speaking up about potential threats that can hinder or disrupt work operations.

Though we find convincing evidence in favor of the situational perspective for why employees do or don’t speak up, our study has its limitations. For instance, it was conducted in East Asia, where people ascribe to cultural value of collectivism and social norms might play a stronger role than in the more individualist West. Despite this caveat, our research suggests that if you want your employees to be more vocal and contribute ideas and opinions, you should actively encourage this behavior and reward those who do it.

9 Out of 10 People Are Willing to Earn Less Money to Do More-Meaningful Work

bulentgultek/Getty Images

bulentgultek/Getty ImagesIn his introduction to Working, the landmark 1974 oral history of work, Studs Terkel positioned meaning as an equal counterpart to financial compensation in motivating the American worker. “[Work] is about a search…for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor,” he wrote. Among those “happy few” he met who truly enjoyed their labors, Terkel noted a common attribute: They had “a meaning to their work over and beyond the reward of the paycheck.”

More than forty years later, myriad studies have substantiated the claim that American workers expect something deeper than a paycheck in return for their labors. Current compensation levels show only a marginal relationship with job satisfaction. By contrast, since 2005, the importance of meaningfulness in driving job selection has grown steadily. “Meaning is the new money, an HBR article argued in 2011. Why, then, haven’t more organizations taken concrete actions to focus their cultures on the creation of meaning?

To date, business leaders have lacked two key pieces of information they need in order to act on the finding that meaning drives productivity. First, any business case hinges on the ability to translate meaning, as an abstraction, into dollars. Just how much is meaningful work actually worth? How much of an investment in this area is justified by the promised returns? And second: How can organizations actually go about fostering meaning?

You and Your Team Series

Making Work More Meaningful

You’re Never Done Finding Purpose at Work

Dan Pontefract

The Research We’ve Ignored About Happiness at Work

André Spicer and Carl Cederström

What to Do When Your Heart Isn’t in Your Work Anymore

Andy Molinsky

We set out to answer these questions at BetterUp this past year, as a follow-up to our study on loneliness at work. Our Meaning and Purpose at Work report, released today, surveyed the experience of workplace meaning among 2,285 American professionals, across 26 industries and a range of pay levels, company sizes, and demographics. The height of the price tag that workers place on meaning surprised us all.

The Dollars (and Sense) of Meaningful Work

Our first goal was to understand how widely held the belief is that meaningful work is of monetary value. More than 9 out of 10 employees, we found, are willing to trade a percentage of their lifetime earnings for greater meaning at work. Across age and salary groups, workers want meaningful work badly enough that they’re willing to pay for it.

The trillion dollar question, then, was just how much is meaning worth to the individual employee? If you could find a job that offered you consistent meaning, how much of your current salary would you be willing to forego to do it? We asked this of our 2,000+ respondents. On average, our pool of American workers said they’d be willing to forego 23% of their entire future lifetime earnings in order to have a job that was always meaningful. The magnitude of this number supports one of the findings from Shawn’s recent study on the Conference for Women. In a survey of attendees, he found that nearly 80% of the respondents would rather have a boss who cared about them finding meaning and success in work than receive a 20% pay increase. To put this figure in perspective, consider that Americans spend about 21% of their incomes on housing. Given that people are willing to spend more on meaningful work than on putting a roof over their heads, the 21st century list of essentials might be due for an update: “food, clothing, shelter — and meaningful work.”

A second related question is: How much is meaning worth to the organization? Employees with very meaningful work, we found, spend one additional hour per week working, and take two fewer days of paid leave per year. In terms of sheer quantity of work hours, organizations will see more work time put in by employees who find greater meaning in that work. More importantly, though, employees who find work meaningful experience significantly greater job satisfaction, which is known to correlate with increased productivity. Based on established job satisfaction-to-productivity ratios, we estimate that highly meaningful work will generate an additional $9,078 per worker, per year.

Additional organizational value comes in the form of retained talent. We learned that employees who find work highly meaningful are 69% less likely to plan on quitting their jobs within the next 6 months, and have job tenures that are 7.4 months longer on average than employees who find work lacking in meaning. Translating that into bottom line results, we estimate that enterprise companies save an average of $6.43 million in annual turnover-related costs for every 10,000 workers, when all employees feel their work is highly meaningful.

A Challenge and an Opportunity

Despite the bidirectional benefits of meaningful work, companies are falling short in providing it. Our study found that people today find their work only about half as meaningful as it could be. We also found that only 1 in 20 respondents rated their current jobs as providing the most meaningful work they could imagine having.

This gap presents both a challenge and an opportunity for employers. Top talent can demand what they want, including meaning, and will jump ship if they don’t get it. Employers must respond or lose talent and productivity. Building greater meaning in the workplace is no longer a nice-to-have, it’s an imperative.

Among the recommendations we offer in our report are these critical three:

Bolster Social Support Networks that Create Shared Meaning.

Employees who experience strong workplace social support find greater meaning at work. Employees who reported the highest levels of workplace social support also scored 47% higher on measures of workplace meaning than did employees who ranked their workplaces as having a culture of poor social support. The sense of collective, shared purpose that emerges in the strongest company cultures adds an even greater boost to workplace meaning. For employees who experience both social support and a sense of shared purpose, average turnover risk reduces by 24%, and the likelihood of getting a raise jumps by 30%, compared to employees who experience social support, but without an accompanying sense of shared purpose.

Simple tactics can amplify social connection and shared purpose. Explicitly sharing experiences of meaningful work is an important form of social support. Organizations can encourage managers to talk with their direct reports about what aspects of work they find meaningful, and get managers to share their perspectives with employees, too. Managers can also build in time during team meetings to clearly articulate the connection between current projects and the company’s overall purpose. Employees can more easily see how their work is meaningful when team project goals tie into a company’s larger vision.

Adopting these habits may require some coaching of managers, as well as incentivizing these activities, but they can go a long way toward building collective purpose in and across teams.

As Shawn’s book Big Potential demonstrates, social support is also a key predictor of overall happiness and success at work. His recent study of a women’s networking conference demonstrated that such support outside the workplace drives key professional outcomes, such as promotions.

Make Every Worker a Knowledge Worker.

Our study found that knowledge workers experience greater meaning at work than others, and that such workers derive an especially strong sense of meaning from a feeling of active professional growth. Knowledge workers are also more likely to feel inspired by the vision their organizations are striving to achieve, and humbled by the opportunity to work in service to others.

Research shows that all work becomes knowledge work, when workers are given the chance to make it so. That’s good news for companies and employees. Because when workers experience work as knowledge work, work feels more meaningful.

As such, all workers can benefit from a greater emphasis on creativity in their roles. Offer employees opportunities to creatively engage in their work, share knowledge, and feel like they’re co-creating the process of how work gets done.

Often, the people “in the trenches” (retail floor clerks, assembly line workers) have valuable insights into how operations can be improved. Engaging employees by soliciting their feedback can have a huge impact on employees’ experience of meaning, and helps improve company processes. A case study of entry-level steel mill workers found that when management instituted policies to take advantage of workers’ specialized knowledge and creative operational solutions, production uptime increased by 3.5%, resulting in a $1.2M increase in annual operating profits.

Coaching and mentoring are valuable tools to help workers across all roles and levels find deeper inspiration in their work. Managers trained in coaching techniques that focus on fostering creativity and engagement can serve this role as well.

A broader principle worth highlighting here is that personal growth — the opportunity to reach for new creative heights, in this case above and beyond professional growth — fuels one’s sense of meaning at work. Work dominates our time and our mindshare, and in return we expect to find personal value from those efforts. Managers and organizations seeking to bolster meaning will need to proactively support their employees’ pursuit of personal growth and development alongside the more traditional professional development opportunities.

Support Meaning Multipliers at All Levels.

Not all people and professions find work equally meaningful. Older employees in our study, for instance, found more meaning at work than do younger workers. And parents raising children found work 12% more meaningful that those without children. People in our study in service-oriented professions, such as medicine, education and social work, experienced higher levels of workplace meaning than did administrative support and transportation workers.

Leverage employees who find higher levels of meaning to act as multipliers of meaning throughout an organization. Connect mentors in high meaning occupations, for instance, to others to share perspectives on what makes work meaningful for them. Provide more mentorship for younger workers. Less educated workers — who are more likely to work in the trenches — have valuable insights on how to improve processes. They’d be prime candidates for coaching to help them find ways to see themselves as knowledge workers contributing to company success.

Putting Meaning to Work

The old labor contract between employer and employee — the simple exchange of money for labor — has expired; perhaps it was already expired in Terkel’s day. Taking its place is a new order in which people demand meaning from work, and in return give more deeply and freely to those organizations that provide it. They don’t merely hope for work to be meaningful, they expect it — and they’re willing to pay dearly to have it.

Meaningful work only has upsides. Employees work harder and quit less, and they gravitate to supportive work cultures that help them grow. The value of meaning to both individual employees, and to organizations, stands waiting, ready to be captured by organizations prepared to act.

November 5, 2018

Sisterhood Is Scarce

From the Women at Work podcast:

Listen and subscribe to our podcast via Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | RSS

Download the

discussion guide

for this episode

Join our

online community

The glass ceiling is the classic symbol of the barrier women bump into as we go through our careers. But for women of color, that barrier is more like a concrete wall. If we’re going to reduce workplace sexism and racism, women of all ethnicities need to work together. And it will be tough to do that unless we feel more connected to each other.

We talk with professors Ella Bell Smith and Stella Nkomo about how race, gender, and class play into the different experiences and relationships white women and women of color have at work. They explain how those differences can drive women apart, drawing from stories and research insights in their book, Our Separate Ways.

Guests:

Ella L.J. Bell Smith is a professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth.

Stella M. Nkomo is a professor at the University of Pretoria, in South Africa.

Resources:

Our Separate Ways: Black and White Women and the Struggle for Professional Identity , by Ella L.J.E. Bell Smith and Stella M. Nkomo

“How Black Women Describe Navigating Race and Gender in the Workplace,” by Maura Cheeks

“Why Aren’t There More Asian Americans in Leadership Positions?” by Stefanie K. Johnson and Thomas Sy

“Asian Americans Are the Least Likely Group in the U.S. to Be Promoted to Management,” by Buck Gee and Denise Peck

Sign up for the Women at Work newsletter.

Fill out our survey about workplace experiences.

Email us here: womenatwork@hbr.org

Our theme music is Matt Hill’s “City In Motion,” provided by Audio Network.

Research: Self-Disruption Can Hurt the Companies That Need It the Most

Fuse/Getty Images

Fuse/Getty ImagesWhen innovations threaten to disrupt an industry by replacing an old business model with a new one, incumbents need to invest in that model in order to survive. That’s the conventional wisdom, and it’s given rise to popular mantra “Disrupt or Be Disrupted.”

If you’re dealing with innovations that have led to a dominant new business model in your industry, that advice is sound, as the leaders of Netflix and Blockbuster can tell you. But what if an innovation poses a threat, and you can’t yet tell whether it has genuinely transformative potential? What are the costs and benefits of self-disruption at that uncertain stage?

These are rarely studied questions. Almost all of the research available on the topic of self-disruption focuses on how well incumbents respond to innovations after the they have enabled new models to take over an industry. They might focus on how incumbents cope with the rapid obsolescence of their old capabilities, say, or with internal resistance to inevitable change. That’s valuable information, of course, but it shines no light on the problem of how to respond to potentially threatening innovation that has yet to generate a dominant new business model.

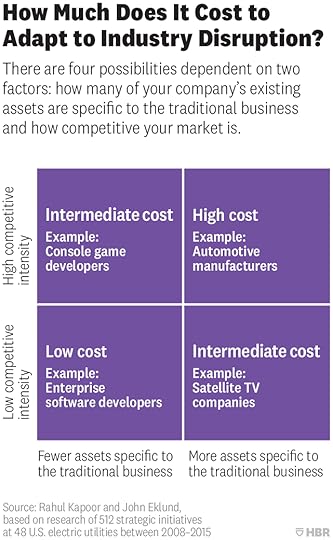

Getting at that problem isn’t easy, because the data about what works are hard to come by. A few years ago, though, we realized that a valuable set of data was available about the U.S. electric utility sector, in which the existing model for energy generation, which has prevailed for a century, may now be giving way to a new one. We studied the sector for three years and came up with some very interesting findings about the “adjustment costs” that companies incur when they disrupt themselves. We’ll soon publish our findings in full in the journal Organizational Science, but below we’ll recap the highlights of the article, in which we identify adjustment costs in a variety of situations for self-disrupters, provide a framework for how companies can identify the locus and intensity of those costs, and lay out different strategies to mitigate them.

A rare natural experiment

In the traditional model of electricity generation, large power plants produce power at a centralized location, which operates at a considerable distance from the points of consumption. Since the mid-2000s, however, this model has been under threat from a new, decentralized model, in which electricity is generated on a much smaller scale near or at the point of use, often through a combination of rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, batteries, and the digital management of the electricity grid.

For our study, we collected data on 512 strategic initiatives, both centralized and decentralized, launched by 48 leading U.S. electric utilities during 2008-2015—a period in which the decentralized model was in its uncertain, nascent phase. We examined how each initiative impacted a company’s value through changes in its stock price, which we used as a proxy for determining the short-term costs of self-disruption. We validated our quantitative approach by reviewing several case studies of U.S. and international electric utilities.

As we studied the data, we realized that we were looking at the results of a rare natural experiment on the costs of adjustment to self-disruption. The information presented itself along two big dimensions: the power-generation assets owned by the centralized power plants (i.e., their production capacity, which obviously varied considerably) and the competitive intensity of their markets (which ranged from perfect competition to near monopoly, because of regulatory differences between states).

We looked in particular at firms with generation assets that would become redundant if the disruptive model became dominant. Firms with generation assets above the median, we found, incurred adjustment costs that were approximately $800M higher than those below the median. And firms operating in more competitive markets incurred approximately $600M higher cost of self-disruption than those in less competitive markets. These factors—the generation asset base and the external competitive environment in which they operated—are two of the main drivers of value for electric utilities. And when they’re high, we discovered, they make the adjustment costs of self-disruption high, at least in the short term.

We summarized our findings on this point in a simple but revealing two-by-two.

Quadrant 1, not surprisingly, is the danger zone. Companies here operate in highly competitive environments and have high stocks of assets that they have accumulated to support the traditional business. They’re the ones potentially most threatened by innovation—and, ironically, as the figure makes clear, they’re also the ones who pay the highest adjustment cost for disrupting themselves in response to that innovation.

What companies fall into this quadrant? Traditional automotive manufacturers certainly do. Competition in the industry is fierce, and many of these manufacturers’ key assets, such as factories, technology expertise, and distribution networks, are only useful in the traditional business, which is predicated on widespread vehicle ownership. These companies now have to contend with the rising threat to their traditional business model from autonomous vehicles and ride sharing, but, as this figure shows, the adjustment costs for pursuing these innovations will be high. The Ford Motor Company has learned this hard way in recent years.

Companies in Quadrant 4 are likely to have the lowest cost of self-disruption, because they operate in markets that are not especially competitive, and because their key assets can easily be deployed in new places and for new purposes. Think here of enterprise-software developers such as Microsoft, SAP, and Oracle, who are undergoing the disruptive change to cloud-based software service. These companies have high market share in their specific application domains, which means competition isn’t a major concern, and many of their key assets—in software development and enterprise-customer relationships, for example—can easily be adapted to fit the new model.

Companies in Quadrants 2 and 3 bear intermediate costs of self-disruption, but the locus of those costs varies between, respectively, the external competitive environment and the internal asset base.

Companies in Quadrant 2 tend to bear relatively high indirect costs, because of the greater threat of cannibalization and the greater conflict for resources in a highly competitive environment. Traditional game developers facing the emergence of mobile gaming fall into this quadrant—Electronic Arts and Nintendo, for example. Their stock of assets—intellectual property, game-development capabilities—is compatible with mobile gaming, but they operate in a highly competitive market where product life is short and consumer preferences change quickly.

Companies in Quadrant 3 tend to bear relatively high direct costs, because they need to develop new assets and lack expertise in implementing the new business. Companies in the satellite TV industry fall into this quadrant. The industry has been dominated by DirecTV (AT&T) and Dish Network, both of which have prospered without much competition by selling packages of channels at relatively high prices. Their key asset stocks are networks of satellites that very specifically serve the existing business—which is a problem now that companies such as Netflix and Amazon are threatening to disrupt the satellite model by offering low-cost video-on-demand packages via the Internet.

Companies in the same industry can fall into different quadrants, of course, depending on their asset configurations and their competitive positioning. This is the case in the retail sector, where brick-and-mortar operations are under threat from online commerce. The cost of self-disruption is high in this environment for retailers such as JC Penney and Sears, whose asset base consists of a vast array of stores that they operate in a highly competitive market. It is considerably lower, on the other hand, for luxury retailers such as Louis Vuitton and Gucci, which face much less competition and whose greatest asset is often their brand.

Costs and benefits

The framework we’ve outlined above can be very useful to leaders who are considering the costs and benefits of self-disruption.

Companies in Quadrant 4 are well positioned to embrace disruption. A case in point is Microsoft, which—drawing on many of its existing assets in software development, customer relationships, and networking technologies—has embraced a shift from on-premise software licensing to cloud-based software and infrastructure services, where it faces low competitive intensity within the enterprise market.

Companies in Quadrant 1, on the other hand, are not well positioned. They are the most threatened by disruptive innovations and have to adapt—but they have to do this in a highly competitive environment, without the benefit of leveraging their existing asset stocks. If the companies in this quadrant rush to self-disrupt during the nascent period of innovation and change, they are likely to incur significant adjustment costs, which may doom their prospects. These companies would do much better to adopt a wait-and-see approach, in which they shy away from taking on major initiatives on their own until the initial uncertainty around disruptive innovations is resolved. Alternatively, they might explore disruptive initiatives via strategic alliances with partners from outside the industry—as GM is doing with Lyft, for example, by pursuing an alliance to help manage the shift toward ride sharing and autonomous vehicles.

Companies in Quadrant 2 can benefit from dividing their assets between their existing and disruptive business models, but in doing so they have to mitigate the indirect adjustment costs that accompany such sharing of assets, and the conflicts that will arise from cannibalization and resource allocation in a highly competitive environment. Here a viable approach is to pursue self-disruption only in niche market, so as to avoid cannibalization and to leverage asset bases such as brand and pre-existing IP, which are less constrained by the traditional business. Nintendo opted for this approach when it began investing in mobile gaming, by focusing on games that are unique to smartphones.

Companies in Quadrant 3 don’t operate in as competitive an environment as those in Quadrant 2, but they incur greater adjustment costs when it comes to developing asset bases that support the new business. A viable approach here is to pursue an active M&A and alliance strategy to build new asset stocks, as Dish Network has managed to do successfully.

Our study has a number of obvious limitations. We examined data from only one industry; we used stock-price data as a proxy for long-term performance; and we were unable, because of a lack of data, to explore how firms might lower adjustment costs internally. Still, we feel our findings represent an important contribution to the strategy literature, because they help explain why some incumbents are able to adapt successfully to disruptive innovation while others are not.

Can AI Address Health Care’s Red-Tape Problem?

Westend61/Getty Images

Westend61/Getty ImagesProductivity in the United States’ health care industry is declining — and has been ever since World War II. As the cost of treating patients continues to rise, life expectancy in America is beginning to fall. But there is mounting evidence that artificial intelligence (AI) can reverse the downward spiral in productivity by automating the system’s labyrinth of labor-intensive, inefficient administrative tasks, many of which have little to do with treating patients.

Administrative and operational inefficiencies account for nearly one third of the U.S. health care system’s $3 trillion in annual costs. Labor is the industry’s single largest operating expense, with six out of every 10 people who work in health care never interacting with patients. Even those who do can spend as little as 27% of their time working directly with patients. The rest is spent in front of computers, performing administrative tasks.

Insight Center

The Future of Health Care

Sponsored by Medtronic

Creating better outcomes at reduced cost.

Using AI-powered tools capable of processing vast amounts of data and making real-time recommendations, some hospitals and insurers are discovering that they can reduce administrative hours, especially in the areas of regulatory documentation and fraudulent claims. This allows health care employees to devote more of their time to patients and focus on meeting their needs more efficiently.

To be sure, as we’ve seen with the adoption of electronic health records (EHR), the health care industry has a track record of dragging its feet when it comes to adopting new technologies — and for failing to maximize efficiency gains from new technologies. It was among the last industries to accept the need to digitize, and by and large has designed digital systems that doctors and medical staff dislike, contributing to warnings about burnout in the industry.

Adopting AI, however, doesn’t require the Herculean effort electronic health records (EHRs) did. Where EHRs required billions of dollars in investment and multi-year commitments from health systems, AI is more about targeted solutions. It involves productivity improvements made in increments by individual organizations without the prerequisite collaboration and standardization across health care players required with EHR adoption.

Indeed, AI solutions dealing with cost-cutting and reducing bureaucracy — where AI could have the biggest impact on productivity — are already producing the kind of internal gains that suggest much more is possible in health care players’ back offices. In most cases, these are experiments launched by individual hospitals or insurers.

Here, we analyze three ways AI is chipping away at mundane, administrative tasks at various health care providers and achieving new efficiencies.

Faster Hospital Bed Assignments

Quickly assigning patients to beds is critical to both the patients’ recovery and the financial health of hospitals. Large hospitals typically employ teams of 50 or more bed managers who spend the bulk of their day making calls and sending faxes to various departments vying for their share of the beds available. This job is made more complex by the unique requirements of each patient and the timing of incoming bed requests, so it’s not always a case of not enough beds but rather not enough of the right type at the right time.

Enter AI with the capability to help hospitals more accurately anticipate demand for beds and assign them more efficiently. For instance, by combining bed availability data and patient clinical data with projected future bed requests, an AI-powered control center at Johns Hopkins Hospital has been able to foresee bottlenecks and suggest corrective actions to avoid them, sometimes days in advance.

As a result, since the hospital introduced its new system two years ago, Johns Hopkins can assign beds 30% faster. This has reduced the need to keep surgery patients in recovery rooms longer than necessary by 80% and cut the wait time for beds for incoming emergency room patients by 20%. The new efficiencies also permitted Hopkins to accept 60% more transfer patients from other hospitals.

All of these improvements mean more hospital revenue. Hopkins’s success has prompted Humber River Hospital in Toronto and Tampa General Hospital in Florida to create their own AI-powered control centers as well.

Easier and Improved Documentation

Rapid collection, analysis and validation of health records is another place where AI has begun to make a difference. Health care providers typically spend nearly $39 billion every year to ensure that their electronic health records comply with about 600 federal guidelines. Hospitals assign about 60 people to this task on average, one quarter of whom are doctors and nurses.

This calculus changes when providers use an AI-powered tool developed in cooperation with electronic health record vendor Cerner Corporation. Embedded in physicians’ workflow, the AI tool created by Nuance Communications offers real-time suggestions to doctors on how to comply with federal guidelines by analyzing both patient clinical data and administrative data.

By following the AI tool’s recommendations, some health care providers have cut the time spent on documentation by up to 45% while simultaneously making their records 36% more compliant.

Automated Fraud Detection

Fraud, waste, and abuse also continues to be a consistent drain. Despite an army of claims investigators, it annually costs the industry as much as $200 billion.

While AI won’t eliminate those problems, it does help insurers better identify the claims that investigators should review — in many cases, even before they are paid — to more efficiently reduce the number of suspect claims making it through the system. For example, startup Fraudscope has already saved insurers more than $1 billion by using machine learning algorithms to identify potentially fraudulent claims and alert investigators prior to payment. Its AI system also prioritizes the claims that will yield the most savings, ensuring that time and resources are used where they will have the greatest impact.

Getting Ready for AI

When it comes to cutting health care’s administrative burden through AI, we are only beginning to scratch the surface. But the industry’s ability to amplify that impact will be constrained unless it moves to remove certain impediments.

First, healthcare organizations must simplify and standardize data and processes before AI algorithms can work with them. For example, efficiently finding available hospital beds can’t happen unless all departments define bed space in the same terms.

Second, health care providers will have to break down the barriers that usually exist between customized and conflicting information technology systems in different departments. AI can only automate the transfer of patients from operating rooms to intensive care units (ICU) if both departments’ IT systems are able to communicate with each other.

Finally, the industry’s productivity will not improve as long as too many health care personnel continue in jobs that don’t add value to the business by improving outcomes. Health care players need to begin reducing their workforces by taking advantage of the industry’s 20% attrition rate and automating tasks, rather than filling positions on autopilot.

The task of improving productivity in health care by automating administrative tasks with AI will not be completed quickly or easily. But the progress already achieved by AI solutions is encouraging enough for some to wonder whether re-investing savings from it might also ultimately cut the overall cost of health care as well as improve its quality. For an industry known for its glacial approach to change, AI offers more than a little light at the end of a long tunnel.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers