Rick Harsch's Blog, page 7

March 24, 2016

Incident in Dodge City (Kansas)

It was my first day in an armed class, but I was calm, you might say dead-eyed, looking out at my 22 kids, their 44 66 eyes. Nothing need change. Good morning class, that’s how I usually began. I smiled broadly. ‘Good morning class.’ I said. It’s just that easy. ‘So, please open your text books to page’—click…click…clickclickclick…’please set your text books aside, as we are going to something a little different today. Heck, why open an English text book when you all already speak English? No, instead today we’re going to have a little fun. How many of you speak any Spanish?’ click…a deafening chorus of clicks…’Me neither, nor should I, nor should you…’ What was I thinking…but wait, there was a hand slowly rising, as if, as if…’Yes, Carlos.’

Testimony of —————————, professor of English, Dodge City Technical College, September 19, 2016.

March 21, 2016

Insect Arms, My First Two Critics, parts I and II

2.99 at http://www.amazon.com/dp/B01D3Y2LLK

the appearance of death to a hindu woman….2.99 at amazon.com

INSECT ARMS: My First Critics

After events unfolded during the 1990 in India that inspired the novel The Appearance of Death to a Hindu Woman, I found myself adrift in the United States, seeking work to support my writing. I became a taxi driver, a job that did not allow space and time for writing. Seeking a solution, I found that friend was willing to support me with $3,ooo so that I could go to Mexico, where I would settle on the coast north of Merida and get down to writing my novel. In the mean time, a different friend told me about the bizarre phenomenon of writing workshops, places attached to universities where writers could go to learn how to write. Naturally I balked at the thought, hearing him out while trying to get the attention of the bartender…but eventually he got through to me that the elite writing school, the Iowa Writers Workshop, was just four hours away from where we were and that if I went there with financial aid I would have two years to earn a master’s degree in fine arts, or, as I thought of it, two years to write my India novel. Weighing the two options, I decided I would indeed apply to writing schools, and I did so, to five of them, including the University of Southern Mississippi, which is where I wanted to go, entirely in consideration of the climate. And the did accept me, but with limited financial aid. So I couldn’t afford it. As it turned out, it was the Iowa workshop that offered me enough money to live and write for two years, an odd bit of luck I did not recognize at the time. I had sent them 100 pages of a novel called Taxi Cabaret, the Adventures of a Fat Nihilist, and apparently it attracted much attention. The university contacted me as I was driving the cab, and when I put the caporegime of the workshop on hold—something I later found out one generally dare not do—and she understood I was in a taxi as we spoke and she found it exhillarating in the way royalty quaintly does a peasant juggling five cats, good for a few minutes amusement.

I quit the taxi driving as soon as I could afford to and began intensive reading in preparation to writing the novel. I had written paragraphs here and there that are still in the novel, but had been unable to sustain the writing, just to think it through. As a consequence a guide to the unwritten book was laid like railroad track in my subconscious, awaiting the preparatory work of deepening the necessary knowledge if Indian myth and philosophy.

I arrived in Iowa City, to live on Iowa Avenue, to attend the State of Iowa’s university and its Iowa Writers Workshop—I arrived as a rube. I never thought of myself as a rube, being suburban raised, but I had an old-fashioned view of literature, how it was written, what it was, where I fit in its schemata. And I expected great things of the workshop; not of the actual teaching/learning, rather assuming that I would meet terrific writers and spend two years among them, all of us inspiring each other toward greater writings. I had no idea what the process was really like.

To a degree, my highest expectations were met in that more than a few people were indeed excellent writers and generous artistic souls. Not that it matters, but they were in the minority. The majority fit in many ways between those folk and the two I will describe, my first two critics of the India novel, which I first submitted about thirty pages of, though it was after I had already learned that a workshop was a seminar held in a garden of pettiness, jealousy, and itinerant spite.

These two were quite remarkable:

I think I referred to the guy as the bloat-headed midget with insect arms. [Homonculus!That’s what it was–ever since I wrote that I had this feeling something wasn’t quite right, yes, the bloatheaded homunculus with insect arms! what a relief!]His real name was J.C. Luxton. He was indeed short, had a pretty big head, and with his elbows drilled into their pivots on the table his arms from the elbow down (up, actually) seemed all he had to swivel about; so yes, the short arms may well have been an optical illusion. None of this would have disturbed me enough to bundle it into some laughs had he not been such a shit. His outstanding characteristic as a seminar conversant was the inability to reform his persona in the face of overwhelming evidence that the jokes he was laughing had been but partially uttered and were not funny to anyone else, so that he was a self-alienating little arm-waver whom others treated politely by, as with ephemeroptera, allowing him to go about his privacy in our presence as long as he desired. More painful was the fate of his mate, another shorty, Amy Charles, who was equally condescending, though less comic a presence, sitting like dark contagion in her seat, who when speaking rapidly dimmed to a hushed tone that only once lured ears closer, for the success of such manipulation must be earned by interesting content and those at the table were instead quickly trained when she opened her mouth to lean further back, stretch their legs, and make noises no one actually heard that were yet louder than her commanding, emptied auditorium voice.

Writers and other artists are often asked to spread their emotions to the pubic, perhaps to atomize them into a consumptive mist that settles into the lungs of the needy. When a work is very personal, autobiographical, the question is often asked, dog tongues dripping drops of droop: how hard was it for you, etc. The answer is: please go look elsewhere for torment. When I was writing about a rather important personal period in my life, my India love and loss, I was working on a novel, not suffering a loss. The worst was over. And I suppose had the worst been all that bad I wouldn’t have been able to work on the novel. All this by way of saying that I was not the least sensitive about the material of the novel, much to the chagrin of the feckless sadists of the workshop.

J.C. and Amy were feckless sadists. How the process worked was copies of our writings were piled up in an office, where class-mates (colleagues! Fellow artists!) would pick them up so they could read and mark them before class, where the author was by rule to sit quietly as the class and at some points an officially stamped writer was to speak of the work before them. Our writer of note, was Marilynne Robinson, and she was in a terrible mood to judge by that semester—during which of approximately 30 review sessions, two student writers per week, she spoke positively three times. She did not speak positively of my first public efforts. Yet that part of the experience was not difficult or even memorable, but for one point she made, which was that we need to be very careful with our words, for at one point in the hallucinogenic flow of my words I had written something that upon a bit of reflection made no sense. She was right; so I remembered that. The rest was abstruse or vague, something like a spell of moderately poor weather is to a busy worker.

The fun part, then, was after the seminar, when we had a pile of our own work that had been marked by 14 other ‘writers’ to take home and sift through. I remember that one of the first things that Luxton wrote was ‘Yoy! Dialogue!’ That, because my excerpt went eight pages without. Already you can see what a demented, nasty little turd he was. The first book to my left that I noticed just now is Middlemarch—seven or eight pages before dialogue. Yoy. The Idiot: I don’t even have to look, dialogue on the second or third page. Green Henry (a Swiss masterwork, less known that one would wish): about fifteen pages. Yoy! and again Yoy! The rest of his remarks escape me but for those that were echoed by the woman he would soon couple with, Amy Charles. She ws more pompous, more condescending, more unconsciously hilarious, than her slightly taller friend: big words. I used big words. Latinate words. She wrote a short essay on my piece, at the end of it, about writers who, and this part was the key to the hilarity of the whole, fall in love with Edgar Allen Poe and thus with big words. I was 34 years old at the time. I recall that Catch-22 had a lot of words I was unfamiliar with in it when I first read it. I suppose Ulysses had a few. Cortazar perhaps. I don’t really know. Catch-22, for some reason, is the only one I recall recalling used ‘big words’ which I defined as those I did not know the meaning of.

So recently I went through The Appearance of Death to a Hindu Woman, preparing it for e-printing. I hadn’t read it for at least 16 years. I was eager to see what those words were. I knew it had to be somewhere near the beginning of the book. And as it turned out I could not find it. The only words I would guess might give a reader trouble were Indian words—the book may or may not require a glossary if it is ever printed. But Latinate words? Yes, we all use them all the time. Big words? I’ll look again, but I would expect that most of my friends know most of the words in the book, and for every one of those they don’t know, they do know one that I do not know. By now, J.C. Luxton probably has a ruler tattooed to his forearm, for I find it unlikely he has changed, and by now he’ll need proof that a word is too long. And I won’t apologize for that last sentence, which had five words too long in it. As for Amy…I made her cry one day. I’m not proud of that fond memory. It was the second year, by which time my novel had been crowned a success by Marilynne Robinson and James Alan McPherson, while she was rooting about for something better than she was capable and had confirmed her place in literature already as one who would never make it, who had not the calling, who had not even the verve to fake it. She saw me out walking and asked me something about my writing that seemed to invite comment on her comments over the past year and few months. I simply told her that her comments were among the least valuable I had ever received, the least helpful, the most misguided and perhaps spiteful. And genuine tears leapt from somewhere behind into her eyes.

Insect Arms, My First Two Critics

the appearance of death to a hindu woman….2.99 at amazon.com

INSECT ARMS: My First Critics

After events unfolded during the 1990 in India that inspired the novel The Appearance of Death to a Hindu Woman, I found myself adrift in the United States, seeking work to support my writing. I became a taxi driver, a job that did not allow space and time for writing. Seeking a solution, I found that friend was willing to support me with $3,ooo so that I could go to Mexico, where I would settle on the coast north of Merida and get down to writing my novel. In the mean time, a different friend told me about the bizarre phenomenon of writing workshops, places attached to universities where writers could go to learn how to write. Naturally I balked at the thought, hearing him out while trying to get the attention of the bartender…but eventually he got through to me that the elite writing school, the Iowa Writers Workshop, was just four hours away from where we were and that if I went there with financial aid I would have two years to earn a master’s degree in fine arts, or, as I thought of it, two years to write my India novel. Weighing the two options, I decided I would indeed apply to writing schools, and I did so, to five of them, including the University of Southern Mississippi, which is where I wanted to go, entirely in consideration of the climate. And the did accept me, but with limited financial aid. So I couldn’t afford it. As it turned out, it was the Iowa workshop that offered me enough money to live and write for two years, an odd bit of luck I did not recognize at the time. I had sent them 100 pages of a novel called Taxi Cabaret, the Adventures of a Fat Nihilist, and apparently it attracted much attention. The university contacted me as I was driving the cab, and when I put the caporegime of the workshop on hold—something I later found out one generally dare not do—and she understood I was in a taxi as we spoke and she found it exhillarating in the way royalty quaintly does a peasant juggling five cats, good for a few minutes amusement.

I quit the taxi driving as soon as I could afford to and began intensive reading in preparation to writing the novel. I had written paragraphs here and there that are still in the novel, but had been unable to sustain the writing, just to think it through. As a consequence a guide to the unwritten book was laid like railroad track in my subconscious, awaiting the preparatory work of deepening the necessary knowledge if Indian myth and philosophy.

I arrived in Iowa City, to live on Iowa Avenue, to attend the State of Iowa’s university and its Iowa Writers Workshop—I arrived as a rube. I never thought of myself as a rube, being suburban raised, but I had an old-fashioned view of literature, how it was written, what it was, where I fit in its schemata. And I expected great things of the workshop; not of the actual teaching/learning, rather assuming that I would meet terrific writers and spend two years among them, all of us inspiring each other toward greater writings. I had no idea what the process was really like.

To a degree, my highest expectations were met in that more than a few people were indeed excellent writers and generous artistic souls. Not that it matters, but they were in the minority. The majority fit in many ways between those folk and the two I will describe, my first two critics of the India novel, which I first submitted about thirty pages of, though it was after I had already learned that a workshop was a seminar held in a garden of pettiness, jealousy, and itinerant spite.

These two were quite remarkable:

I think I referred to the guy as the bloat-headed midget with insect arms. His real name was J.C. Luxton. He was indeed short, had a pretty big head, and with his elbows drilled into their pivots on the table his arms from the elbow down (up, actually) seemed all he had to swivel about; so yes, the short arms may well have been an optical illusion. None of this would have disturbed me enough to bundle it into some laughs had he not been such a shit. His outstanding characteristic as a seminar conversant was the inability to reform his persona in the face of overwhelming evidence that the jokes he was laughing had been but partially uttered and were not funny to anyone else, so that he was a self-alienating little arm-waver whom others treated politely by, as with ephemeroptera, allowing him to go about his privacy in our presence as long as he desired. More painful was the fate of his mate, another shorty, Amy Charles, who was equally condescending, though less comic a presence, sitting like dark contagion in her seat, who when speaking rapidly dimmed to a hushed tone that only once lured ears closer, for the success of such manipulation must be earned by interesting content and those at the table were instead quickly trained when she opened her mouth to lean further back, stretch their legs, and make noises no one actually heard that were yet louder than her commanding, emptied auditorium voice.

March 18, 2016

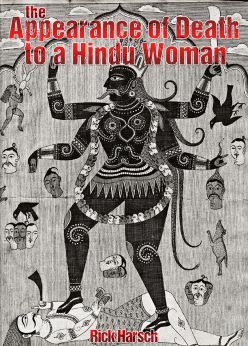

The APPEARANCE OF DEATH TO A HINDU WOMAN is published

2.99 USD

That link should take you to the page where this novel that has been waiting over 20 years for publication is now available.

The description of the book is as follows

The Appearance of Death to a Hindu Woman explores the spaces where love and delusion, myth and existence weave sinuously, rhapsodically, through the Indian world. An American man loses his Indian love during, significantly, the Kali Yuga, the age of decadence, when the spiritual succumbs to the profane. Attempting through yogic/tantric methods to return to his love, the man makes a pilgrimage that may or may not be real, may or may not succeed, as he journeys through Indian historic and mythological time, eliciting the great loves of Indian lore, Radha and Krishna, Rama and Sita, Kannagi and Kovalan, attempting to overcome the dark forces that would prevent their union. The prose at times adopts the techniques of Indian poetry, and ranges from realistic encounters in and with India to a dramatically poetic and surreal absorption into an India unknown and hitherto unavailable to the outsider. The narrator, by virtue of his knowledge, rises beyond the deluded novice, while by virtue of his poetic and romantic nature as pilgrim defies the distance between historian and subject, in this beautiful and romantic work that ultimately is an act of submission to the mysterious forces of love.

March 17, 2016

Coming Soon at E-mazon

March 15, 2016

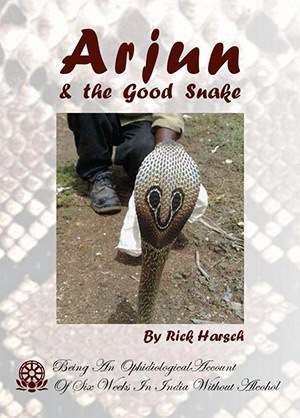

Rick Harsch publishes Arjun and the Good Snake (again and cheaper e-style)

By RayKosmick | 15.03.2016 | Books, Fortunate Finds, New Releases, Uncategorised

First of all, let me get the following out of the way: yes, I count the writer Rick Harsch among “real-life” friends (i.e., not one of those you only “talk” to via one of the antisocial networking sites), so my review of his first e-book (but hardly Rick’s first book – he has previously published a heap of those… what were they… oh, paper artefacts!) might not be entirely objective (as if any review is). The thing is, Rick’s relentlessly critical outlook but nevertheless remarkably positive opinion of my own debut novel was what I desperately needed at a time when my confidence in my scribbling ability was faltering on a daily basis, and he has also been invaluable in his efforts to help me polish my own books and get them in front of readers. This was, as far as my own previous experience had indicated, rather unusual for “old-school” writers such as Rick.

First of all, let me get the following out of the way: yes, I count the writer Rick Harsch among “real-life” friends (i.e., not one of those you only “talk” to via one of the antisocial networking sites), so my review of his first e-book (but hardly Rick’s first book – he has previously published a heap of those… what were they… oh, paper artefacts!) might not be entirely objective (as if any review is). The thing is, Rick’s relentlessly critical outlook but nevertheless remarkably positive opinion of my own debut novel was what I desperately needed at a time when my confidence in my scribbling ability was faltering on a daily basis, and he has also been invaluable in his efforts to help me polish my own books and get them in front of readers. This was, as far as my own previous experience had indicated, rather unusual for “old-school” writers such as Rick.

As it happens, Harsch is not (yet?) a member of the modern, agreeable, happy-go-lucky gang of “indie authors”: he hails from the “olden” days when the stereotypical image of writers was still – with good reason, I suppose – that of obstinate, loopy, unsociable, disgruntled old geezers who most likely hate all other writers, but especially any who might materialise in their vicinity. After all, Rick was, once upon a time, on his way to becoming quite renowned for his traditionally-published and widely acclaimed “Driftless Trilogy” (The Driftless Zone, Billy Verite, and The Sleep of Aborigines), which has also been translated into French and made its way into the curriculum of the somewhat obscure University of Tasmania (as Rick defines it in Snake, “the intellectual center of the only block of land to exterminate allits aboriginals“). However – rather unsurprisingly, if you know what an onerous conundrum of uncalled-for incidents tends to surround Rick most of the time – due to an extremely unfortunate sequence of events, including but not limited to the vastly premature death of his Hollywood agent, a bitter though hilarious (to an external observer) dispute with his subsequent literary agent, the bankruptcy of his French publisher and other similarly torturous circumstances, Rick Harsch’s tenacious infiltration of the world literary canon has been on a rather involuntary and undeserved hiatus of late. The infamous downward spiral of the traditional publishing industry that has got out of control after the advent of e-readers has only further complicated Rick’s theretofore cunning world-domination scheme.

In light of all of the above (as well as because I practically forced him to), Rick has recently decided to join the indie author tribe. Arjun and the Good Snake is the first book of his to be re-released as an e-book, hopefully in a series of others that should follow. I’ve had the honour of formatting it for e-readers, and it should look good – I certainly hope so, and if it doesn’t, feel free to complain to me and hold me personally responsible, and I mean that! This I did most happily, for Snake has been, to date, my favourite book of Rick’s (with the possible exception of an upcoming “paper” one, which is still in the works); though I, unfortunately, haven’t yet had the pleasure of reading the Driftless Trilogy, because it is, sadly, out of print. (Rick is currently looking at the possibility of resurrecting it, but the fact that he doesn’t have the manuscripts in the electronic form will make this “project” difficult and, above all, long-winded.)

Reading Arjun and the Good Snake for the first time a few years back was the perfect way of getting to know Rick better, along with all of his numerous remarkable qualities as well as considerable faults. As he puts it himself in the introduction to Snake, “No character, especially that of the author, is safe” (from assassination, I guess). The (sort of) journal supposedly focuses on the six weeks in India (without alcohol, woe was Rick!) that the author spent on a quest to track down a cobra and hopefully also a Russell’s viper, the ophidian preference of his son. However, the “diary” is interspersed with the author’s intimate musings and ruminations: on his own failings, particularly the harrowing alcohol addiction (paradoxically, simultaneously soul-sucking and soul-giving, as anyone who has ever struggled with their share of problems with alcoholism will surely know); on his family, especially his relationship with his wife Sasikala and son Arjun; on India and all her unknowable depths; on philosophical, existentialist, even suicidal enigmas; as well as on the various goings-on back at the Slovenian coast, where the author had emigrated from the United States, primarily, as far as I know, to escape oppressive idiocy… Only to witness, to his dismay, the quickening of rabid, unhinged capitalism in a former socialist country, with all the savagery that has entailed.

Arjun and the Good Snake is not an “easy” book. If you’re an ardent believer in the magnificent contemporary Western world and appreciate the constant pursuit of instant gratification, ravenous consumption as well as instantaneous excretion – then this might not be a book for you. However, if you’re willing to put a bit of effort in a literary work rather than just be “entertained” by it, you’ll doubtlessly unearth and come to appreciate many a touching contemplative passage such as, for example, the following:

“We arrived to the sea – and this is where if I were ever to commit suicide, the time would be as appropriate as it would get, a wretched man standing apart from the alienated cluster representing all he’s got, unable to enjoy himself alone, alienated even from a circumstance too familiar to generate true despair; the waves relentlessly formed and reformed with their concealed force, spent themselves falsely, the sea sucking in with greed: There is much to be learned standing with pants rolled above the knees and feet planted on damp sand as the lace of water passes ankle high, and then the sand around the feet is stripped away with a surprising, even sinister, force that badly wants to take me under, too…“

March 12, 2016

Streets of Old Izola: Smrekarjeva

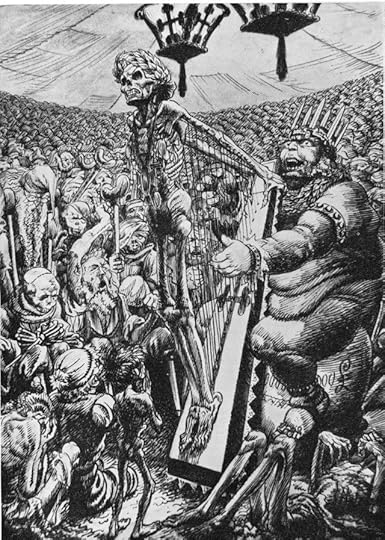

Hinko Smrekar’s Ode to the World War, or Harp of Death

On the other hand, artists were celebrated by Slovenes – dead artists even so to this day. Before Slovenia began using the euro, their currency was the tolar, which included a religious author (he wrote the first two books printed in Slovene and looked a great deal like Vincent Price), a natural historian and author, two painters, an architect, a composer, a poet, and a writer of fiction. That’s a lot of money, leaving out only a mathematician, who was worth fifty tolars. Hinko Smrekar was a poor and unlucky artist born in 1883 in Ljubljana, where he was also shot dead, in 1942 by the occupying Germans. His work is quite varied, largely because he had difficulty earning money for his artworks, so he illustrated books, and was even the first Slovene to decorate tarok cards (tarok is a popular card game with regional variations that may or may not be a corruption of bridge combined with tarot created by drunken Hungarian soldiers on an orgiastic night in a Romanian gypsy town). The image above is Mars, one of many of the world’s gods of war, ‘On his head he has a crown of knives; he is sitting on a bag of money and is singing and playing to crippled human figures. A skeleton (war hero), bearing a laurel wreath, has climbed onto the crosspiece of the harp (coffin): “He is depicted, playing – on the instrument of human passion = a starved skeleton, wrapped in the desire for glory, which is getting an echo from the coffin. The skeleton is decorated with pendants of various awards from holy and secular authorities. A great mass of people are gathered around the monstrous instrument – they are literally crammed in like matchsticks, human money worshippers who are staring, devotedly bowing, sighing from starvation, all engrossed and following the money monster’s every move. They are staring at it with feverish greed in a nervous throb, staring and staring into the sinister cauldron of voices from the coffin and its cadaverously hollow echoes.” (Elko Justin, “Hinko Smrekar in his pictures”, Tovarish, 1948, no. 41) [from Damir Globočnik, writing in: http://www.livesjournal.eu/library/lives6/damgl6/reflection6.htm]

This is a man who deserved a great street and indeed got one.

Smrekar seen from Kristan Sq. Arches and recesses by day

For some time, Smrekarjeva, Hinko Smrekar Street, was my favorite in Izola, and for the simplest of reasons: for the first few years of living in Izola I had no regular place to visit within the old town beyond Ljubljana Street, Manzioli Square, and the beach, which I usually reached by walking along the shore. When I did venture further in, it was usually at night while walking the dogs, random walks in darker lanes, some of surprising length, like Hinko’s street. And I never knew precisely where I was and so never knew where I would emerge, and though the possibility were decidedly undramatic, such as Manzioli Square and Kristan Square, each of these had several streets entering them, and I never recognized where I was before actually entering into the square. As for Smrekar’s Street in particular, there was also the combinaton of the curving street and the irregularity of the buildings that at night made me feel I was negotiating a cubist painting, the buildings closing and opening at the eaves, sudden open spaces revealing ultimately closed spaces or lanes that took me into entirely lost zones. One left turn is still Smrekar Street, opens onto By The Doors Street, yet turn out in its continuation to remain Smrekar Street. One wrong turn and you may be stuck at night in Courtyard Street, seeking in vain that slice between buildings that is the shortcut to Koper Street, yet in the dark of night seems to shift from one corner to another, more elusive as one’s panic rises. Worse, the connection to Courtyard is a two or three meter stretch of street with no name, no entrances, an indefinable space where all I have ever seen is a garbage wagon and various large pieces of refuse piled around it.

Growing sinister as the sun slides toward the horizon

Growing sinister as the sun slides toward the horizon

Innocent by day

The middle length of Smrekar

Down Alma Vivode, a concrete onion dome.

A stylish lintel

Behold

The requisite ornamentation of days gone by: on the left un-retouched, on the right recently painted. Note the free mixture of stlyes, even to the point of faux columns.

A final stretch of Smrekar Smrekar ends where the van is parked

March 1, 2016

Letters from Uzbekistan: Mysterious Miss Uzbekistan is Donald Trump’s Daughter

According to my source in the Uzbeki tourism agency, the mysterious Miss Uzbekistan from 2013 is Donald Trump’s daughter by his Slovene wife, Melania Trump. Arslan Levantinov has insisted he has proof that he cannot trust to send by post and will only turn over to me, and only me, in person. From his short note: ‘Look at the photo and tell me how old you think she is.?

Below is the story until yesterday’s communique from Mr. Levantinov:

Miss Uzbekistan is 18 and plays the piano. But no one in her homeland has heard of her

RAKHIMA GANIEVA, the 18-year-old representing Uzbekistan at the 2013 Miss World pageant in Indonesia has all the right credentials. She’s beautiful, sporty, plays the piano and describes herself as “cheerful and serious at the same time”.

There’s only one problem: no one in Uzbekistan has ever heard of her, says The Times.

The central Asian republic is better known for its exports of gold, uranium and natural gas, than beauty queens. Indeed, officials in Tashkent, the capital, say the country has never staged a Miss Uzbekistan contest.

A spokesman for the Taskent modelling agency where Ganieva trained “briefly” as a 15-year-old told Eurasianet.org that she “never passed through any special selection process in Uzbekistan”.

“If there had been a process to choose a young lady for this competition, I can assure you that a much more beautiful model would have been chosen,” he added. “I’m sorry that Ganieva is choosing to build a career on lies.”

So, who is Ganieva? Her biography on the official Miss World website reveals that she’s “very exited and happy” to be representing Uzbekistan at the 63rd Miss World contest. She adds that she’s handy with a tennis racket, likes to study history and loves weighty Russian authors including Chekhov, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

February 23, 2016

Letters from Uzbekistan: Sex Tourism

From the blog of M. Gautham Machaiah

From the blog of M. Gautham MachaiahSex tourism: Is Tashkent going the Thailand way?

Note: The Government of Uzbekistan has now imposed curbs on prostitution. With this, lets hope Tashkent becomes a family destination, as it deserves to be [note: this, which is not true, was the work of Mr. Arslan Levantinov. RH]

M. Gautham Machaiah

“Sir, do you want a girl?” This is what the cab driver is most likely to ask you in Tashkent, rather than, “Where do you want to go?”

Welcome to the Thailand of Central Asia.

Though it might be difficult to replace Thailand as the sex capital of the world, Tashkent with its booming underground prostitution industry, is set to give Pattaya and Bangkok a run for their money.

Tashkent, which is now the capital of Uzbekistan after the disintegration of Soviet Union, is one of the most beautiful cities in the world with its immaculate tree lined streets, wide walkways, large parks, historic monuments, imposing buildings, 8-D theatres, ballet shows, snow capped mountains, excellent public transport system, pristine rivers and pollution free environment. But these hold no interest to the average sex-hungry traveller.

The stage was set the moment we landed at the Tashkent airport, with prying eyes virtually stripping every passing woman. This being the first day, we were treated to a gala dinner and belly dance, where our Indian group mates were at their obnoxious best. After some failed attempts to grope the girls, the guys wanted some ‘action’ which the tour operators readily organised elsewhere.

The second day was a shocker. After a hurried sightseeing trip of the City, our tour operator pompously took over the guide’s microphone in the coach and announced two interesting options for the evening. One was the Villa, the other being lap dance.

Now, what’s a Villa? Listen to what our illustrious operator had to say: “A Villa is like a farm house on the outskirts of Tashkent. It has a massage parlour and sauna, a dance floor and two-three bedrooms. You can have a massage, dance with the girls, have some Vodka and then take the girl of your choice to the bedroom. That is not all. After you have had your share of fun, you can even swap your girl with others.”

And then, what about lap dance? “It is a strip tease where the girls will dance completely naked. They will grind on your lap and you are free to fondle them to your heart’s content,” the operator volunteered.

Exciting options indeed!

We then adjourned for lunch so that a considered view could be taken on which of these options to choose from. But even one hour after the lunch, there was no sign of the operators. A little bit of probing revealed that they were busy collecting the advance from those who had chosen their options. After some heckling by me, everybody was herded into the coach to continue the tour in which most were not interested.

“We have come here to see the place, not to drink, dance and womanise,” I protested, but the tour operator shamelessly responded, “That is what people come to Tashkent for. There is nothing to see here.” That was when I realised Tashkent was being sold as a sex destination and the operators were doubling up as touts and pimps. Obviously, a cut from the Villa and strip tease goes to them.

The operator then went on to proudly announce that in the next few days he would fly in a 180- strong contingent from India on an exclusive sex package. “We have factored in all costs ranging from Villas, lap dance and night clubs. There will be no sightseeing, only fun.” While a trip to Tashkent costs less than Rs 50,000, the Gujarati team had shelled out over Rs 1 lakh each,” the operator boasted.

The second half of the City tour ended sooner than it began. While we decided to call it a day, most others made their way to the Villas.

The next day on, we decided to break away from the group and explore the City on our own, but that too did not really solve our problem. Every taxi driver we hired was only interested in making a fast buck by selling to us what seemed to be the most easily available ware – young women.

One night when we were returning to the hotel after dinner, the only question the Hindi speaking cabbie asked us was, “Do you want girls?” We politely declined first and then firmly when he persisted. Instead, we asked him to take us to a pharmacy as my friend was suffering from a headache. The driver was so upset by our refusal that he drove straight to the hotel and declared, “There are no pharmacies in the City.”

February 21, 2016

Montefiore’s “The Court of the Red Tsar”

If Cheney would be Stalin, who would be Beria? Ok, so Cheney would be Stalin and Beria. Or let Wolfowitz be Stalin. Bolton as Molotov? Close enough. Obama? Let’s say Bulganin. This regime unleashed a terror the likes of which have only been seen in previous regimes with different Stalin/Berias. Only they did it outside their own country. What is remarkable in the case of Stalin is that he did it to his own people (and to a lesser extent those in his sphere of control to the west). Is it justifiable to compare this ‘Monster’ to our monsters? I think so. Our comparisons are effective and sometimes necessary, particularly when we begin to make the mistake of looking at politics in terms of good versus evil. Stalin and gang’s crude and massively murderous rapid industrialization is certainly ugly to read about, but what was it if not a compression of the Industrialization that took place in England, which certainly exceeded Stalin’s efforts in terms of vicitms, coming as it did along with colonial rapine and the complete gutting of India, where the British orchestrated famines as bad as that in the Ukraine in the early 30s.

Simon Sebag Montefiore’s The Court of the Red Tsar has little new to say in broad terms about Stalin and his crew, because Stalin has been written about repeatedly, from the early and percipient biography by the all but forgotten Isaac Deutscher to the perhaps definitive biographer Robert Service. But Montefiore has more information at his disposal than any writer has yet had and he made the decision to write a rather gossipy book that reads like a South American novel of a despot. Even his language is that of a novelist at times, freely using the word dwarf, mostly to describe the sadistic (the book is filled with sadists, but it has to be said here anyway) shorty Yezhov, who headed the inquisitions after Yagoda and before Beria. So the book is highly entertaining, more so than any other biography of Stalin, giving specific inside story after inside story, quote after quote, so that a bland statement like ‘Stalin was merciless even in his closest circles, ordering the executions of…’ is given horrific life by closely acquainting the reader with these people, what they said, and how they subsequently suffered: there are many accounts of specific tortures (One thing I learned was that I have been wrong all these years to believe that a paranoid Stalin was quite practical about offing his enemies, simply sending them to the Lubyanka to be shot; given the extraordinary numbers of political murders [millions] this had to be to some extent true, but he often requested various tortures be applied and in many personal cases took an interest in the reactions of the victims.)

Since so little of the general story was new to me, I didn’t begin marking the book until late, around page 500 or so. Here are some of these bits:

Stalin: ‘Leave them in peace. We can always shoot them later.’

‘The film star Zoya Fyodorovna was picked up by these Chekists at a time when she was still breastfeeding her baby. Taken to a party where there were no other guests, she was joined by Beria whom she begged to let her go as her breasts were painful. »Beria was furious.« The officer who was taking her home mistakenly handed her a bouquet at the door. When Beria saw, he shouted: »It’s a wreath not a bouquet. May they rot on your grave!« She was arrested afterwards.

‘The film actress Tatiana Okunevskaya was even less lucky: at the end of the war, Beria invited her to perform for the Politburo. Instead they went to a dacha. Beria plied her with drink, »virtually pouring the wine into my lap. He ate greedily, tearing at the food with his hands, chattering away.« Then »he undresses, rolls around, eyes ogling, an ugly, shapeless toad. »’Scream or not, doesn’t matter’,« he said. »’Think and behave accordingly.’« Beria softened her up by promising to releaase her beloved father and grandfather from prison and then raped her. He knew very well that both had already been executed. She too was arrested soon afterwards and sentenced to solitary confinement. Felling trees in the Siberian taiga, she was saved, like so many others, by the kindness of ordinary people.’

Like I say, the book fleshes out novelistically what we for the most part already new. One of the most astonishing things we knew was how Stalin refused to accept the fact that Germany was going to attack his country and refused to make any efforts to prepare, in fact did the opposite so as not to offend Hitler, who might take troop movements and such as a provocation. This book does not bore on the topic, for instance Montefiore finds a quote from Stalin who is told less than a week before Operation Barbarossa that a spy in the Luftwaffe confirms the impending attack, and Stalin replies ‘Tell the »source« in the Staff of the German Air Force to fuck his mother!«

Other matters of particular interest to me are Churchill’s calling his agreement to divide post-war Europe into states controlled by East and West, using percentages (Greece 90% west, 10% East…) a ‘naughty document’; And, moreso, I was pleased that an anecdote I have been telling for years regarding attempted assassinations of Tito was factual. Some letters were found on Stalin’s Kremlin desk, apparently the contents unknown to any but Stalin. In my old version there were three, two from Lenin, one from Tito. In this version there were five, but only three could be recalled by witnesses. One was indeed from Lenin, scolding Stalin for speaking ill of Krupskaya, one from Bukharin asking why he needed to die, and the third was from Tito that read ‘Stop sending assassins to muder me…If this doesn’t stop, I will send a man to Moscow and there’ll be no need to send any more.’

Finally, grading this book. The effort, the travels, the inexhaustible reading and travelling the author undertook…this alone suggests five of five stars. The writing itself, weaving the personal and the enormous historic without jarring the reader, managing to tell readers what they quite likely already know without boring them, that too suggests five of five stars. And, more difficult than anything probably, telling much the same personal tales of victims, endless victims close to Stalin, their stories not significantly different from all the others for the most part, without either appealing to the basest instincts of the reader (I, for one, could have used more specifics) or boring us—that deserves a five as well.