Insect Arms, My First Two Critics

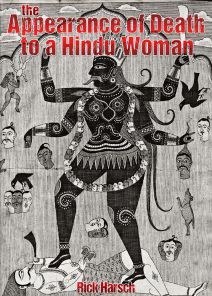

the appearance of death to a hindu woman….2.99 at amazon.com

INSECT ARMS: My First Critics

After events unfolded during the 1990 in India that inspired the novel The Appearance of Death to a Hindu Woman, I found myself adrift in the United States, seeking work to support my writing. I became a taxi driver, a job that did not allow space and time for writing. Seeking a solution, I found that friend was willing to support me with $3,ooo so that I could go to Mexico, where I would settle on the coast north of Merida and get down to writing my novel. In the mean time, a different friend told me about the bizarre phenomenon of writing workshops, places attached to universities where writers could go to learn how to write. Naturally I balked at the thought, hearing him out while trying to get the attention of the bartender…but eventually he got through to me that the elite writing school, the Iowa Writers Workshop, was just four hours away from where we were and that if I went there with financial aid I would have two years to earn a master’s degree in fine arts, or, as I thought of it, two years to write my India novel. Weighing the two options, I decided I would indeed apply to writing schools, and I did so, to five of them, including the University of Southern Mississippi, which is where I wanted to go, entirely in consideration of the climate. And the did accept me, but with limited financial aid. So I couldn’t afford it. As it turned out, it was the Iowa workshop that offered me enough money to live and write for two years, an odd bit of luck I did not recognize at the time. I had sent them 100 pages of a novel called Taxi Cabaret, the Adventures of a Fat Nihilist, and apparently it attracted much attention. The university contacted me as I was driving the cab, and when I put the caporegime of the workshop on hold—something I later found out one generally dare not do—and she understood I was in a taxi as we spoke and she found it exhillarating in the way royalty quaintly does a peasant juggling five cats, good for a few minutes amusement.

I quit the taxi driving as soon as I could afford to and began intensive reading in preparation to writing the novel. I had written paragraphs here and there that are still in the novel, but had been unable to sustain the writing, just to think it through. As a consequence a guide to the unwritten book was laid like railroad track in my subconscious, awaiting the preparatory work of deepening the necessary knowledge if Indian myth and philosophy.

I arrived in Iowa City, to live on Iowa Avenue, to attend the State of Iowa’s university and its Iowa Writers Workshop—I arrived as a rube. I never thought of myself as a rube, being suburban raised, but I had an old-fashioned view of literature, how it was written, what it was, where I fit in its schemata. And I expected great things of the workshop; not of the actual teaching/learning, rather assuming that I would meet terrific writers and spend two years among them, all of us inspiring each other toward greater writings. I had no idea what the process was really like.

To a degree, my highest expectations were met in that more than a few people were indeed excellent writers and generous artistic souls. Not that it matters, but they were in the minority. The majority fit in many ways between those folk and the two I will describe, my first two critics of the India novel, which I first submitted about thirty pages of, though it was after I had already learned that a workshop was a seminar held in a garden of pettiness, jealousy, and itinerant spite.

These two were quite remarkable:

I think I referred to the guy as the bloat-headed midget with insect arms. His real name was J.C. Luxton. He was indeed short, had a pretty big head, and with his elbows drilled into their pivots on the table his arms from the elbow down (up, actually) seemed all he had to swivel about; so yes, the short arms may well have been an optical illusion. None of this would have disturbed me enough to bundle it into some laughs had he not been such a shit. His outstanding characteristic as a seminar conversant was the inability to reform his persona in the face of overwhelming evidence that the jokes he was laughing had been but partially uttered and were not funny to anyone else, so that he was a self-alienating little arm-waver whom others treated politely by, as with ephemeroptera, allowing him to go about his privacy in our presence as long as he desired. More painful was the fate of his mate, another shorty, Amy Charles, who was equally condescending, though less comic a presence, sitting like dark contagion in her seat, who when speaking rapidly dimmed to a hushed tone that only once lured ears closer, for the success of such manipulation must be earned by interesting content and those at the table were instead quickly trained when she opened her mouth to lean further back, stretch their legs, and make noises no one actually heard that were yet louder than her commanding, emptied auditorium voice.