Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 42

June 4, 2014

Inside Brunel's great iron ship - SS Great Britain

The 'great' may have been quietly dropped out of beleaguered Britain (will it exist at all after the Scottish referendum?) but Brunel's iron ship, the biggest ship ever built at the time, the first to be powered by both sail and steam, is still Great in every sense of the word. I haven't seen it since they finished the restoration, so was eager to see the ship with all six masts erected and the interior re-constructed. The SS Great Britain was launched in 1843 and finally scuttled in the Falklands in 1937 - in service for almost a hundred years. Money was raised to bring it back to Bristol in 1970 and return it to the dock where it had been built.

Bristol dock is the place to see tall ships. The ship below is the Kaskelot, between television appearances.

First glimpse of the SS Great Britain is the gilded stern with gallery windows and gilding like the old 17th century sailing ships.

They've very carefully restored only sections of the ship - leaving the hull below the waterline in the same condition it was in when the ship was a hulk rescued from the Falkland Islands. The iron plates have been 'conserved' leaving the holes visible.

The original wooden rudder is on show.

Up on deck, the length of the ship is amazing!

She was very impressive under sail (and steam) as this 19th century painting shows. I would have loved to have been sailing on her then!

She was very roomy below decks too, though even the First Class cabins were very small. Only the First Class toffs could stretch their legs on the promenade deck, or eat in the plush dining room.

First class cupboard - whoops - Cabin!There was a massive kitchen with several huge ovens for bread, cakes and roasts. The crates of cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, ducks and geese on deck were destined to end up here.

First class cupboard - whoops - Cabin!There was a massive kitchen with several huge ovens for bread, cakes and roasts. The crates of cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, ducks and geese on deck were destined to end up here.

There was even a fully equipped doctor's surgery, complete with leeches.

It was a fantastic experience - unlike some tourist trips - and worth every penny. If you want to know what it was like to be a passenger on board one of those ocean going sailing ships this is brilliant. You can explore all the different decks to your heart's content and even climb the rigging up to the crow's nest. That'll be me - next time!

Bristol dock is the place to see tall ships. The ship below is the Kaskelot, between television appearances.

First glimpse of the SS Great Britain is the gilded stern with gallery windows and gilding like the old 17th century sailing ships.

They've very carefully restored only sections of the ship - leaving the hull below the waterline in the same condition it was in when the ship was a hulk rescued from the Falkland Islands. The iron plates have been 'conserved' leaving the holes visible.

The original wooden rudder is on show.

Up on deck, the length of the ship is amazing!

She was very impressive under sail (and steam) as this 19th century painting shows. I would have loved to have been sailing on her then!

She was very roomy below decks too, though even the First Class cabins were very small. Only the First Class toffs could stretch their legs on the promenade deck, or eat in the plush dining room.

First class cupboard - whoops - Cabin!There was a massive kitchen with several huge ovens for bread, cakes and roasts. The crates of cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, ducks and geese on deck were destined to end up here.

First class cupboard - whoops - Cabin!There was a massive kitchen with several huge ovens for bread, cakes and roasts. The crates of cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, ducks and geese on deck were destined to end up here.

There was even a fully equipped doctor's surgery, complete with leeches.

It was a fantastic experience - unlike some tourist trips - and worth every penny. If you want to know what it was like to be a passenger on board one of those ocean going sailing ships this is brilliant. You can explore all the different decks to your heart's content and even climb the rigging up to the crow's nest. That'll be me - next time!

Published on June 04, 2014 02:20

June 1, 2014

Norman Nicholson, love, music and geology

Black Combe with sunshine and cloudIt's been a brutal week, and I've driven more than 500 miles for events connected with Norman Nicholson's Centenary - another interview for a BBC documentary, library talks (including one where nobody braved the torrential rain to listen!), workshops and finally, yesterday, a day in Millom with the Norman Nicholson Society discussing Norman's early love affair with a Russian Jewish emigree in the sanatorium - mostly conducted by letter from their respective beds.

Black Combe with sunshine and cloudIt's been a brutal week, and I've driven more than 500 miles for events connected with Norman Nicholson's Centenary - another interview for a BBC documentary, library talks (including one where nobody braved the torrential rain to listen!), workshops and finally, yesterday, a day in Millom with the Norman Nicholson Society discussing Norman's early love affair with a Russian Jewish emigree in the sanatorium - mostly conducted by letter from their respective beds. Norman at 19, his father Joe, and ?Sylvia Lubelsky

Norman at 19, his father Joe, and ?Sylvia Lubelsky

Norman was fascinated by, and very knowledgeable about, Geology and his poetry is littered with references to the bedrock we all stand on and take very much for granted. Professor Brian Whalley took us on a walk round the streets of Millom to look at some of the oldest rocks on earth, embedded in the stone walls around the town.

Amazing what we walk past and never look at. There's Skiddaw Slate, several different kinds of sandstone, volcanic granite and limestone, from the ancient to relatively modern (2 or 3 hundred million years anyway!) in one wall alone, arranged in a style that's unique to this area.

And in some of them you can see the waves of those ancient seas still etched in the stone.

The sun shone and there were lovely views of the fells. The day ended with the first performance of a newly commissioned piece of music, composed by award-winning young composer Harry Whalley - a setting for strings of Norman's poem 'Seven Rocks'. St George's Church, with its memorial stained glass window, had the perfect acoustic for the Gildas Trio who came up from Manchester for the performance. Unforgettable!

The Gildas Trio - part of the Gildas Quartet

The Gildas Trio - part of the Gildas Quartet Norman Nicholson's Memorial Window by Christine Boyce

Norman Nicholson's Memorial Window by Christine BoyceThis morning I'm about to get on a train for Bristol and Weston-super-Mare. Another suitcase, another train .......

Published on June 01, 2014 01:56

May 29, 2014

A Journey from Fact to Fiction - interviewed by Jane Davis

I've not been blogging this week due to a full schedule of events connected with the Norman Nicholson centenary, but today you can find me on Jane Davis blog - 'Meet the Author' talking about moving from writing biography to fiction and the complications of a writer's life! Jane is the winner of the Daily Mail First Novel Award and a very fine writer herself.

Jane found this wonderful quote about writing from Khaled Hosseini. 'A Thievish Undertaking'.

You can find the link here

Jane found this wonderful quote about writing from Khaled Hosseini. 'A Thievish Undertaking'.

You can find the link here

Published on May 29, 2014 08:13

May 23, 2014

Signposts in the Sea

Well, I’ve really lost the plot. I’m having a crazy week running round trying to do a thousand things before I leave for England on Saturday. I have lists and post-it notes everywhere. There are three, very different, book talks to write and a workshop to plan, the house to clean, a pile of ironing, garden to sort out and the fridge to fill for Himself (who will otherwise live on Tuscan sausages and fried eggs while I’m away). Then there are the two guest blogs I promised to write and the emails piling up in the mail box . . .

But I did play truant to have coffee with a friend yesterday and a walk along the beach. The weather has suddenly got warmer and the ‘bagnos’ are opening up. The beaches are no longer a wide, wild expanse of sand, but lined with coloured umbrellas, and they’re bulldozed clean every evening. The amount of rubbish the sea brings in is horrifying - a long tidemark of plastic and pieces of wood, fragments of fishing net - but mostly plastic.

Last time we were down here, someone had been very creative with the rubbish, erecting an ‘installation’ that had a very direct message. It's all made from objects found on the beach.

The Mediterranean is not in good health. A week ago we had an evening walk onto the ‘pontile’ and, when we reached the end of the pier and looked out to the horizon we realised that there were pale blue shapes in the water below us, like scattered flowers, floating in shoals as far as the eye could see and being washed ashore with every wave. We walked back and then down onto the beach to take a look. It was mussel shells, piling up on the sand in drifts that stretched for kilometers. Unfortunately I didn’t have my camera with me to record it. What killed the mussels - millions of them? We still have no idea, and no one else seemed very concerned. The beach cleaning forces are relentless in summer. By morning every last mussel shell had been cleared away.

But the message is clear - we can’t go on treating the planet like this. The signs are there for everyone to see.

But I did play truant to have coffee with a friend yesterday and a walk along the beach. The weather has suddenly got warmer and the ‘bagnos’ are opening up. The beaches are no longer a wide, wild expanse of sand, but lined with coloured umbrellas, and they’re bulldozed clean every evening. The amount of rubbish the sea brings in is horrifying - a long tidemark of plastic and pieces of wood, fragments of fishing net - but mostly plastic.

Last time we were down here, someone had been very creative with the rubbish, erecting an ‘installation’ that had a very direct message. It's all made from objects found on the beach.

The Mediterranean is not in good health. A week ago we had an evening walk onto the ‘pontile’ and, when we reached the end of the pier and looked out to the horizon we realised that there were pale blue shapes in the water below us, like scattered flowers, floating in shoals as far as the eye could see and being washed ashore with every wave. We walked back and then down onto the beach to take a look. It was mussel shells, piling up on the sand in drifts that stretched for kilometers. Unfortunately I didn’t have my camera with me to record it. What killed the mussels - millions of them? We still have no idea, and no one else seemed very concerned. The beach cleaning forces are relentless in summer. By morning every last mussel shell had been cleared away.

But the message is clear - we can’t go on treating the planet like this. The signs are there for everyone to see.

Published on May 23, 2014 00:40

May 19, 2014

Tuesday Poem: Kirsti Whalen - Brave Like

It's almost Tuesday and I'm going a little crazy trying to get things finished before going back to the UK at the end of the week as well as preparing for the 3 talks and the workshop I've got booked for next week. So I apologise for not being able to put up a Tuesday poem of my own. But I'd like to share the wonderful poem on the Tuesday Poem hub by young NZ award winning poet Kirsti Whalen - fantastic word music and you have to read all of it to really appreciate how good it is. It begins:

Kirsti Whalen: Brave Likean excerpt

Gaffer toe inside lake water. Not cold in there. Is not. Like. Imagined. Run, he say. Little eel snap snapping at your toes. Water like mud and thick too. Shallow but. Out. Out, Love Little. Out for it. Little run, Little One. Little One, his name for me.

But we are West. Rules snap snapping. This the other side. East of home and West of an older one. Western Springs. Springs cut with digger and. Birds. Brought here, I think. Nested in. They’re big anyway. Those eels. Those. Churning. Bolstered by old bread languid in mud water. They. Cut slip slither grease like under he nail. Don’t.

Not running.

Angry. I think he is. And it is only yet the flash of a green morning. Jetlag made early us. I. Reckless Little. Loves me. Loves me. Cover concern with sticking plaster disinterest. Cover sweaty water echo with black swan long neck saunter.

Who gives a shit, say he. ...............

To Read the rest of it please click here to access the Tuesday Poem hub. There are lots of good things in the sidebar too.

Kirsti Whalen

Kirsti Whalen

Kirsti Whalen: Brave Likean excerpt

Gaffer toe inside lake water. Not cold in there. Is not. Like. Imagined. Run, he say. Little eel snap snapping at your toes. Water like mud and thick too. Shallow but. Out. Out, Love Little. Out for it. Little run, Little One. Little One, his name for me.

But we are West. Rules snap snapping. This the other side. East of home and West of an older one. Western Springs. Springs cut with digger and. Birds. Brought here, I think. Nested in. They’re big anyway. Those eels. Those. Churning. Bolstered by old bread languid in mud water. They. Cut slip slither grease like under he nail. Don’t.

Not running.

Angry. I think he is. And it is only yet the flash of a green morning. Jetlag made early us. I. Reckless Little. Loves me. Loves me. Cover concern with sticking plaster disinterest. Cover sweaty water echo with black swan long neck saunter.

Who gives a shit, say he. ...............

To Read the rest of it please click here to access the Tuesday Poem hub. There are lots of good things in the sidebar too.

Kirsti Whalen

Kirsti Whalen

Published on May 19, 2014 12:47

May 17, 2014

Chasing the Rose: A book about gardens and stories

Chasing the Rose: An Adventure in Venetian Country

Andrea di Robilant

Rosa Moyesii - one of the original wild species roses from ChinaI love roses, particular the old varieties with names that suggest a long history - who was Madame Albert Carriere? Does Paul’s Himalayan Musk really come from northern India? And I love the Chinese species roses like Rosa Moyesii imported by travellers hundreds of years ago – and the Persian roses mentioned in the Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Rosa Moyesii - one of the original wild species roses from ChinaI love roses, particular the old varieties with names that suggest a long history - who was Madame Albert Carriere? Does Paul’s Himalayan Musk really come from northern India? And I love the Chinese species roses like Rosa Moyesii imported by travellers hundreds of years ago – and the Persian roses mentioned in the Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Rosa Omar Khayyam

Rosa Omar Khayyam

‘Look to the blowing Rose about us--"Lo, Laughing," she says, "into the world I blow, At once the silken tassel of my Purse Tear, and its Treasure on the Garden throw." ‘

So you can see why I was immediately intrigued by this novel-length Kindle single , currently only £1.49.

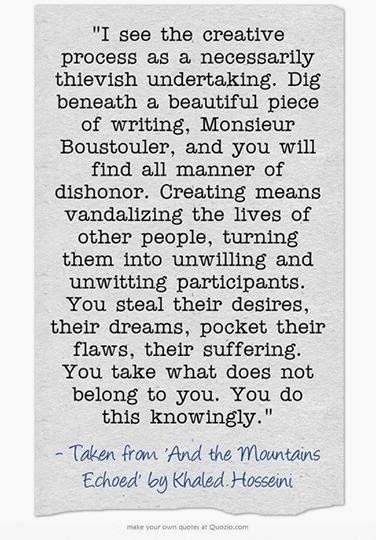

Andrea di Robilant had an ancestor, Alvise Mocenigo, who lived at the end of the 18th century and who had a wife called Lucia who became a friend of Empress Josephine after Napoleon had divorced her. Lucia caught Josephine’s obsession with roses - the rarer the better - and carried many of them back from Paris to the family estate at Alvisipoli in the hills between Trieste and Slovenia in what used to be the Venetian Republic. Apparently Andrea has also written the history of his lively ancestor in 'Lucia: A Venetian Life in the time of Napoleon'. It's not on Kindle, so I've had to buy that in paperback. When will publishers ever learn that one book might lead to another?

Andrea di Robilant had an ancestor, Alvise Mocenigo, who lived at the end of the 18th century and who had a wife called Lucia who became a friend of Empress Josephine after Napoleon had divorced her. Lucia caught Josephine’s obsession with roses - the rarer the better - and carried many of them back from Paris to the family estate at Alvisipoli in the hills between Trieste and Slovenia in what used to be the Venetian Republic. Apparently Andrea has also written the history of his lively ancestor in 'Lucia: A Venetian Life in the time of Napoleon'. It's not on Kindle, so I've had to buy that in paperback. When will publishers ever learn that one book might lead to another?

Old Italian roses don't come more beautiful than 'Tuscany Superb'The Moceniga family estate has long since dissolved into ruin, but on a nostalgic visit to the village of Alvisipoli, Andrea is taken into the gardens - now returned to wilderness - and shown a shrub rose covered in silvery pink flowers. It smells of peaches and raspberries.

Old Italian roses don't come more beautiful than 'Tuscany Superb'The Moceniga family estate has long since dissolved into ruin, but on a nostalgic visit to the village of Alvisipoli, Andrea is taken into the gardens - now returned to wilderness - and shown a shrub rose covered in silvery pink flowers. It smells of peaches and raspberries.

Rosa Moceniga - Photo copyright http://www.cadellerose.blogspot.com

Rosa Moceniga - Photo copyright http://www.cadellerose.blogspot.com

There was a moment of recognition for Andrea. ‘Although I did not know much about roses, everything about it, the delicate color, the sweet fragrance, the way it carried itself - suggested this was an old rose of some importance that had been growing wild in these woods for a very long time’.

Locally it’s known as Rosa Moceniga, but no one knows it’s true name. Andrea plants a cutting in his garden and thinks nothing more of it until one day, researching family history in the Venetian archives, he finds the diaries of Lucia Mocenigo, written while she was in Paris and in the grip of her passion for roses - what was called ‘rosemanie’, an affliction that gave rise to a worldwide rose smuggling operation and a lot of rose snobbery - rivaling ‘tulip fever’ in Holland.

David Austin is one of those trying to preserve the old roses and breed new hybrids.It’s the beginning of a long journey for Andrea, as he becomes obsessed with finding a name for the rose that is the only remnant of Lucia’s love affair with the species. It takes him to France, Slovenia and Umbria, where he meets some of the characters who collect roses. This includes Eleanor and Valentino (a retired Italian bus driver and his green-fingered wife) who - although both old and without money - maintain a rose garden that has become famous for its beauty and the number of forgotten species that bloom there. Eleanor even has an ‘orphan’ section’ for roses whose names have been lost, and it’s there that Andrea finds another Rosa Moceniga.

David Austin is one of those trying to preserve the old roses and breed new hybrids.It’s the beginning of a long journey for Andrea, as he becomes obsessed with finding a name for the rose that is the only remnant of Lucia’s love affair with the species. It takes him to France, Slovenia and Umbria, where he meets some of the characters who collect roses. This includes Eleanor and Valentino (a retired Italian bus driver and his green-fingered wife) who - although both old and without money - maintain a rose garden that has become famous for its beauty and the number of forgotten species that bloom there. Eleanor even has an ‘orphan’ section’ for roses whose names have been lost, and it’s there that Andrea finds another Rosa Moceniga.

One of the old 'moss' roses.A great deal about the history of the rose in Europe has been lost. Altogether only two or three plants on a Parisian list of roses imported from China as the ancestors of modern roses, can still be identified by their original names. We know only a handful of species. Why are names so important? After all, ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet’, as Shakespeare put it - so he already knew about the business of naming roses. All the plant’s history is in its name - where it came from, the family it belongs to, the person who first cultivated it in Europe. Without a name it has no identity and no story. And that is the situation with the temporarily christened Rosa Moceniga. I was happy to find that, at the end of Andrea’s journey, he is successful in naming his rose and making sure that his colourful ancestor Lucia Moceniga is also remembered.

One of the old 'moss' roses.A great deal about the history of the rose in Europe has been lost. Altogether only two or three plants on a Parisian list of roses imported from China as the ancestors of modern roses, can still be identified by their original names. We know only a handful of species. Why are names so important? After all, ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet’, as Shakespeare put it - so he already knew about the business of naming roses. All the plant’s history is in its name - where it came from, the family it belongs to, the person who first cultivated it in Europe. Without a name it has no identity and no story. And that is the situation with the temporarily christened Rosa Moceniga. I was happy to find that, at the end of Andrea’s journey, he is successful in naming his rose and making sure that his colourful ancestor Lucia Moceniga is also remembered.

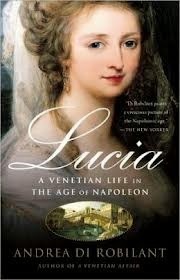

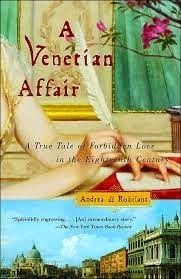

Paul's Himalayan Musk - 4 stories high,in full, spectacular bloom at The MillI found this book absolutely fascinating and heartily recommend it to readers who are interested in travel, gardening, roses - and particularly stories! Now I'm off to find out more about Lucia and the Empress Josephine, but also intrigued by

'A Venetian Affair'

, Andrea de Robilant's account of an affair by another of his ancestors with a beautiful English girl. It's written from letters discovered by his father in their house in Venice and fortunately it is on Kindle.

Paul's Himalayan Musk - 4 stories high,in full, spectacular bloom at The MillI found this book absolutely fascinating and heartily recommend it to readers who are interested in travel, gardening, roses - and particularly stories! Now I'm off to find out more about Lucia and the Empress Josephine, but also intrigued by

'A Venetian Affair'

, Andrea de Robilant's account of an affair by another of his ancestors with a beautiful English girl. It's written from letters discovered by his father in their house in Venice and fortunately it is on Kindle.

Rosa Moyesii - one of the original wild species roses from ChinaI love roses, particular the old varieties with names that suggest a long history - who was Madame Albert Carriere? Does Paul’s Himalayan Musk really come from northern India? And I love the Chinese species roses like Rosa Moyesii imported by travellers hundreds of years ago – and the Persian roses mentioned in the Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Rosa Moyesii - one of the original wild species roses from ChinaI love roses, particular the old varieties with names that suggest a long history - who was Madame Albert Carriere? Does Paul’s Himalayan Musk really come from northern India? And I love the Chinese species roses like Rosa Moyesii imported by travellers hundreds of years ago – and the Persian roses mentioned in the Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam. Rosa Omar Khayyam

Rosa Omar Khayyam‘Look to the blowing Rose about us--"Lo, Laughing," she says, "into the world I blow, At once the silken tassel of my Purse Tear, and its Treasure on the Garden throw." ‘

So you can see why I was immediately intrigued by this novel-length Kindle single , currently only £1.49.

Andrea di Robilant had an ancestor, Alvise Mocenigo, who lived at the end of the 18th century and who had a wife called Lucia who became a friend of Empress Josephine after Napoleon had divorced her. Lucia caught Josephine’s obsession with roses - the rarer the better - and carried many of them back from Paris to the family estate at Alvisipoli in the hills between Trieste and Slovenia in what used to be the Venetian Republic. Apparently Andrea has also written the history of his lively ancestor in 'Lucia: A Venetian Life in the time of Napoleon'. It's not on Kindle, so I've had to buy that in paperback. When will publishers ever learn that one book might lead to another?

Andrea di Robilant had an ancestor, Alvise Mocenigo, who lived at the end of the 18th century and who had a wife called Lucia who became a friend of Empress Josephine after Napoleon had divorced her. Lucia caught Josephine’s obsession with roses - the rarer the better - and carried many of them back from Paris to the family estate at Alvisipoli in the hills between Trieste and Slovenia in what used to be the Venetian Republic. Apparently Andrea has also written the history of his lively ancestor in 'Lucia: A Venetian Life in the time of Napoleon'. It's not on Kindle, so I've had to buy that in paperback. When will publishers ever learn that one book might lead to another? Old Italian roses don't come more beautiful than 'Tuscany Superb'The Moceniga family estate has long since dissolved into ruin, but on a nostalgic visit to the village of Alvisipoli, Andrea is taken into the gardens - now returned to wilderness - and shown a shrub rose covered in silvery pink flowers. It smells of peaches and raspberries.

Old Italian roses don't come more beautiful than 'Tuscany Superb'The Moceniga family estate has long since dissolved into ruin, but on a nostalgic visit to the village of Alvisipoli, Andrea is taken into the gardens - now returned to wilderness - and shown a shrub rose covered in silvery pink flowers. It smells of peaches and raspberries. Rosa Moceniga - Photo copyright http://www.cadellerose.blogspot.com

Rosa Moceniga - Photo copyright http://www.cadellerose.blogspot.comThere was a moment of recognition for Andrea. ‘Although I did not know much about roses, everything about it, the delicate color, the sweet fragrance, the way it carried itself - suggested this was an old rose of some importance that had been growing wild in these woods for a very long time’.

Locally it’s known as Rosa Moceniga, but no one knows it’s true name. Andrea plants a cutting in his garden and thinks nothing more of it until one day, researching family history in the Venetian archives, he finds the diaries of Lucia Mocenigo, written while she was in Paris and in the grip of her passion for roses - what was called ‘rosemanie’, an affliction that gave rise to a worldwide rose smuggling operation and a lot of rose snobbery - rivaling ‘tulip fever’ in Holland.

David Austin is one of those trying to preserve the old roses and breed new hybrids.It’s the beginning of a long journey for Andrea, as he becomes obsessed with finding a name for the rose that is the only remnant of Lucia’s love affair with the species. It takes him to France, Slovenia and Umbria, where he meets some of the characters who collect roses. This includes Eleanor and Valentino (a retired Italian bus driver and his green-fingered wife) who - although both old and without money - maintain a rose garden that has become famous for its beauty and the number of forgotten species that bloom there. Eleanor even has an ‘orphan’ section’ for roses whose names have been lost, and it’s there that Andrea finds another Rosa Moceniga.

David Austin is one of those trying to preserve the old roses and breed new hybrids.It’s the beginning of a long journey for Andrea, as he becomes obsessed with finding a name for the rose that is the only remnant of Lucia’s love affair with the species. It takes him to France, Slovenia and Umbria, where he meets some of the characters who collect roses. This includes Eleanor and Valentino (a retired Italian bus driver and his green-fingered wife) who - although both old and without money - maintain a rose garden that has become famous for its beauty and the number of forgotten species that bloom there. Eleanor even has an ‘orphan’ section’ for roses whose names have been lost, and it’s there that Andrea finds another Rosa Moceniga. One of the old 'moss' roses.A great deal about the history of the rose in Europe has been lost. Altogether only two or three plants on a Parisian list of roses imported from China as the ancestors of modern roses, can still be identified by their original names. We know only a handful of species. Why are names so important? After all, ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet’, as Shakespeare put it - so he already knew about the business of naming roses. All the plant’s history is in its name - where it came from, the family it belongs to, the person who first cultivated it in Europe. Without a name it has no identity and no story. And that is the situation with the temporarily christened Rosa Moceniga. I was happy to find that, at the end of Andrea’s journey, he is successful in naming his rose and making sure that his colourful ancestor Lucia Moceniga is also remembered.

One of the old 'moss' roses.A great deal about the history of the rose in Europe has been lost. Altogether only two or three plants on a Parisian list of roses imported from China as the ancestors of modern roses, can still be identified by their original names. We know only a handful of species. Why are names so important? After all, ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet’, as Shakespeare put it - so he already knew about the business of naming roses. All the plant’s history is in its name - where it came from, the family it belongs to, the person who first cultivated it in Europe. Without a name it has no identity and no story. And that is the situation with the temporarily christened Rosa Moceniga. I was happy to find that, at the end of Andrea’s journey, he is successful in naming his rose and making sure that his colourful ancestor Lucia Moceniga is also remembered.

Paul's Himalayan Musk - 4 stories high,in full, spectacular bloom at The MillI found this book absolutely fascinating and heartily recommend it to readers who are interested in travel, gardening, roses - and particularly stories! Now I'm off to find out more about Lucia and the Empress Josephine, but also intrigued by

'A Venetian Affair'

, Andrea de Robilant's account of an affair by another of his ancestors with a beautiful English girl. It's written from letters discovered by his father in their house in Venice and fortunately it is on Kindle.

Paul's Himalayan Musk - 4 stories high,in full, spectacular bloom at The MillI found this book absolutely fascinating and heartily recommend it to readers who are interested in travel, gardening, roses - and particularly stories! Now I'm off to find out more about Lucia and the Empress Josephine, but also intrigued by

'A Venetian Affair'

, Andrea de Robilant's account of an affair by another of his ancestors with a beautiful English girl. It's written from letters discovered by his father in their house in Venice and fortunately it is on Kindle.

Published on May 17, 2014 03:31

May 14, 2014

John Masefield and Big Boats for Oligarchs

I’ve been enthralled by the sea and boats ever since my mother used to recite John Masefield’s Sea Fever poem to me as a child. Taught by her, I can still recite it from memory

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking,

Where we’re living at the moment, within spitting distance of the Mediterranean, boats are a big part of the economy. Viareggio makes a very good living out of building and servicing the yachts of multi-billionaires. Every winter these floating palaces are moth-balled here in giant sheds, shrouded in plastic wrapping like chrysali, only to emerge in the spring, cleaned and made ready for the odd week when their owners might want them. You can see two of the big sheds in the background below.

The marinas and the boat yards - the 'cantiere navali' are a mass of masts and rigging and the white domes of sophisticated satellite navigation. Spot the oligarch-mobiles in the middle of this one.

The size of some of these ‘yachts’ defies belief - they’re the size of ocean going schooners with 40 metre high masts, electronically powered rigging (no shinning up the mast head here!) and twin screws for powerful propulsion when you’re bored with the novelty of sail.

This one is the size of four large buses end to end.

This one is the size of four large buses end to end.

Beautiful lines

Beautiful lines

40 metre rigging - computer operatedBut they are elegant and beautiful, with slender, classical lines and a grace in the water that would make you weep. These are the boats the oligarchs own. We’ve heard the stories of the parties, the drunken trips out to the islands, the £68,000 champagne bills at the end.

40 metre rigging - computer operatedBut they are elegant and beautiful, with slender, classical lines and a grace in the water that would make you weep. These are the boats the oligarchs own. We’ve heard the stories of the parties, the drunken trips out to the islands, the £68,000 champagne bills at the end.

A photo doesn't convey the scale of these monstersA Saturday in May is the perfect time to wander round the marinas and take a look at the boats being prepared for the summer season.

A photo doesn't convey the scale of these monstersA Saturday in May is the perfect time to wander round the marinas and take a look at the boats being prepared for the summer season.

There are gin palaces for hire.

More modest boats owned by ordinary people.

And monsters for charter if you fancy being an oligarch for a day or so.

Viareggio is very cosmopolitan. In the Bar Under the Sea (Il Bar Sotto il Mare) on the quayside, listening to a Johnny Cash tribute band, we met Australians, English and Germans. Boat builders and engineers and crew, but no Oligarchs. Much more fun.

Jazz under the sea!

Jazz under the sea!

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking,

Where we’re living at the moment, within spitting distance of the Mediterranean, boats are a big part of the economy. Viareggio makes a very good living out of building and servicing the yachts of multi-billionaires. Every winter these floating palaces are moth-balled here in giant sheds, shrouded in plastic wrapping like chrysali, only to emerge in the spring, cleaned and made ready for the odd week when their owners might want them. You can see two of the big sheds in the background below.

The marinas and the boat yards - the 'cantiere navali' are a mass of masts and rigging and the white domes of sophisticated satellite navigation. Spot the oligarch-mobiles in the middle of this one.

The size of some of these ‘yachts’ defies belief - they’re the size of ocean going schooners with 40 metre high masts, electronically powered rigging (no shinning up the mast head here!) and twin screws for powerful propulsion when you’re bored with the novelty of sail.

This one is the size of four large buses end to end.

This one is the size of four large buses end to end.

Beautiful lines

Beautiful lines

40 metre rigging - computer operatedBut they are elegant and beautiful, with slender, classical lines and a grace in the water that would make you weep. These are the boats the oligarchs own. We’ve heard the stories of the parties, the drunken trips out to the islands, the £68,000 champagne bills at the end.

40 metre rigging - computer operatedBut they are elegant and beautiful, with slender, classical lines and a grace in the water that would make you weep. These are the boats the oligarchs own. We’ve heard the stories of the parties, the drunken trips out to the islands, the £68,000 champagne bills at the end. A photo doesn't convey the scale of these monstersA Saturday in May is the perfect time to wander round the marinas and take a look at the boats being prepared for the summer season.

A photo doesn't convey the scale of these monstersA Saturday in May is the perfect time to wander round the marinas and take a look at the boats being prepared for the summer season.There are gin palaces for hire.

More modest boats owned by ordinary people.

And monsters for charter if you fancy being an oligarch for a day or so.

Viareggio is very cosmopolitan. In the Bar Under the Sea (Il Bar Sotto il Mare) on the quayside, listening to a Johnny Cash tribute band, we met Australians, English and Germans. Boat builders and engineers and crew, but no Oligarchs. Much more fun.

Jazz under the sea!

Jazz under the sea!

Published on May 14, 2014 13:56

May 10, 2014

The Centauress - Writing about sensitive issues

This is re-blogged from my monthly slot at Authors Electric.

(Warning: this post contains explicit content which some people may find shocking.)

Tackling sensitive issues in a novel is difficult - yet, if we're to write about the full spectrum of human life then we are going to have to take one on at some point in our writing careers. Personally, I don't believe that the novel is the right medium to conduct a crusade - political or social. Virginia Woolf said that we should never write fiction that encouraged one to 'write a cheque' or 'join a society', but that doesn't mean that we can't address political or social issues. Dickens revealed the horrors of the Victorian underworld, and Catherine Cookson wrote about 20th century prejudices against illegitimacy, class and colour - there are dozens more examples.

I have never, in my life, ever set out to write 'about' an 'issue' in anything but a feature article or media documentary. But my latest novel, The Centauress, tackles the very difficult subject of gender identity. Every year, one in every two thousand babies is born with some kind of gender anomaly. Some of these are quite small and may not get picked up unless there are problems with fertility or they have to take chromosome tests for international athletics. There are perfectly formed girls out there with XY genes. But it’s the physical manifestations that cause the most problems and, because all foetuses start out female and the Y chromosome is only triggered by a ‘wash’ of testosterone in the womb at about 6 weeks, variations in what we consider ‘the norm’ are common.

Historically cases of ‘indeterminate gender’ were usually solved by doing a bit of surgical trimming and bringing the child up as a girl. When I was researching the birth registers in Scotland to trace Catherine Cookson’s father I found an ‘Alexander Davies’ who seemed very promising - born in the right area at the right time with the right name. But when I looked at the register, the baby had been re-registered a few weeks later as a girl ‘Alexandra’. The registrar told me that it was not unusual.

A modern ‘gender assignment’ consultant explained what he called the ‘lop and chop option’ this way - ‘It’s always been easier to dig a hole than to put up a pole’. (The casual terminology made me shudder.) The creation of female genitalia was easier than its reverse and there was a belief among doctors that children were not actually gendered until the second year of their lives, so that if they were dressed in girl’s clothes and given dolls they would grow up to be (almost) perfectly normal young women.

In the USA there were a number of cases where for various reasons (some involving circumcision) babies with damaged penises were turned into girls. A consultant called John Money made research into these children his life’s work. But his belief that physical cosmetic surgery and cultural influence could make a boy into a girl or vice versa didn’t work out. Some of his patients suffered mental health problems, refused to conform, and some even reverted to the clothes and occupations of their original gender, though they had never been told what this was. It is only in the last 20 years that more research has been done into the gendering of the mind before birth - that we are male and female and all the shades in between before we even leave the womb. Plastic surgeons these days try to fit the body to the mind. This is very new and very controversial.

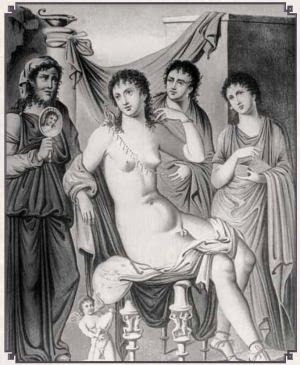

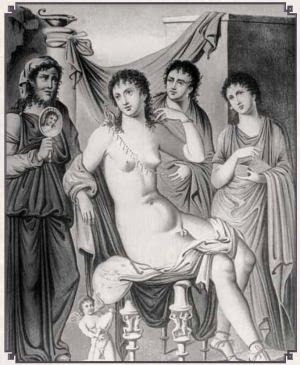

In some extreme cases, babies are born with the complete genitalia of both male and female. We call these hermaphrodites - the union of Hermes and Aphrodite. This has been well documented since written records began and there is a lot of art-work to confirm it too. Some of these drawings and paintings were in the records of ‘freak-shows’ and in 17th and 18th century erotica. But there is one beautiful marble carving (a copy of a Greek original) in the Louvre. It’s called ‘Sleeping Hermaphrodite’ and clearly shows the beautiful body of a woman with male genitalia.

Hermaphroditism has always interested me, since I was a young child of 8 or 9 and my uncle was divorcing his wife. My aunt had run off with another woman and it came up in court (a doctor gave evidence) that this ‘other woman’ was in fact a hermaphrodite. This scandal made the papers and, as children, we got quite used to finding the Sunday papers with holes where the adults had cut out the bits we weren’t supposed to read.

Later I read ‘Herculine Barbin’ - the memoirs of a 19th century woman brought up as a girl, but told when she was a teenager that she was a man. She couldn’t cope with the gender confusion and eventually committed suicide. It’s recently been re-issued edited by Michael Foucault. Herculine Barbin 1868And then in Italy I met the sculptor Fiore de Henriquez, born a hermaphrodite in the years just after the first world war when attitudes to any kind of sexual difference were quite medieval. Fiore was quite open about her dual gender, talking about it freely - a most extraordinary woman with a huge personality - and someone I found utterly fascinating. She was the subject of a biography by my friend Jan Marsh - called ‘Art and Androgyny’ - and there's

a documentary film being made

about her life by US film maker Richard Whymark.

Herculine Barbin 1868And then in Italy I met the sculptor Fiore de Henriquez, born a hermaphrodite in the years just after the first world war when attitudes to any kind of sexual difference were quite medieval. Fiore was quite open about her dual gender, talking about it freely - a most extraordinary woman with a huge personality - and someone I found utterly fascinating. She was the subject of a biography by my friend Jan Marsh - called ‘Art and Androgyny’ - and there's

a documentary film being made

about her life by US film maker Richard Whymark.

When I wrote The Centauress , I didn’t set out to write a book about indeterminate gender. It was just that when the story formed in my head, one of the central dilemmas (and the tragedy) of the main character’s life was being born between sexes at a time when it wasn’t very well understood. As an adult woman, after the failure of her first serious love affair, Zenobia paints herself as an ambiguous Centauress - in Shakespeare’s words from King Lear, ‘Down from the waist they’re centaurs/Though women all above’. The figure of the Centauress was Zenobia’s image of the body she had been born with - neither one thing nor the other, but a merging of both.

Image of Centauress taken from Etruscan potteryIn the novel, my other main character, Alex, has to research this aspect of Zenobia’s life in order to understand why her life has been so turbulent and her relationships so chaotic. In particular, she needs to find out why Zenobia’s mother hated her so much. Their relationship had been mutually destructive, poisoned by blame and shame. Zenobia’s friend and companion, Concetta, tells Alex that ‘There is no hatred like that between a mother and daughter, because there are also such deep ties – it is a hatred that has roots that curl themselves around the heart and strangle it.’ But Zenobia’s mother had been unable to cope with the shame of giving birth to a child that was imperfect. It was a blow to her own femininity. Zenobia blames her mother for attempting to turn her into a ‘normal’ girl.

Image of Centauress taken from Etruscan potteryIn the novel, my other main character, Alex, has to research this aspect of Zenobia’s life in order to understand why her life has been so turbulent and her relationships so chaotic. In particular, she needs to find out why Zenobia’s mother hated her so much. Their relationship had been mutually destructive, poisoned by blame and shame. Zenobia’s friend and companion, Concetta, tells Alex that ‘There is no hatred like that between a mother and daughter, because there are also such deep ties – it is a hatred that has roots that curl themselves around the heart and strangle it.’ But Zenobia’s mother had been unable to cope with the shame of giving birth to a child that was imperfect. It was a blow to her own femininity. Zenobia blames her mother for attempting to turn her into a ‘normal’ girl.

I grew up at a time when feminism was attempting to tell us that men and women were basically the same and that any admission of difference was to give substance to the argument that women were inferior because they were different from men. But I never believed that. We are different - we think differently and we have different skills. This should be valued, not denied. Tennyson (not exactly a feminist) once wrote that ‘there is no equality that does not take account of difference’ - and he was right. Gender difference is only one kind of difference used to put people down.

Anne Fausto-Sterling, Professor of Women's studies and Biology at Brown University, and author of The Five Sexes, writes about the complexities of gender very intelligently, if anyone wants to know more about the subject.

This novel has allowed me to think quite a lot about the way that writers and artists, both male and female think and work. We are conditioned to think in a binary way. My character Zenobia says proudly ‘I can see both sides, because, you see, I am both sides’. I like to believe that our different perspectives illuminate the whole; male and female and every shade in between, all together making one.

The Centauress was published on the 21st April and is available from Amazon.co.ukand from Amazon.com

The Centauress was published on the 21st April and is available from Amazon.co.ukand from Amazon.com

"Bereaved biographer Alex Forbes goes to war-ravaged Croatia to research the life of celebrity artist Zenobia de Braganza and finds herself at the centre of a family conflict over a disputed inheritance. At the Kaštela Visoko Alex uncovers a mutilated photograph, stolen letters and a story of indeterminate gender, passion and betrayal. But can she believe what she is being told? In order to discover the truth about Zenobia, Alex travels to Istria, Venice, New York and London and, in working through the narrative of Zenobia’s life, Alex begins to make sense of her own and finds joy and love in a new relationship."

(Warning: this post contains explicit content which some people may find shocking.)

Tackling sensitive issues in a novel is difficult - yet, if we're to write about the full spectrum of human life then we are going to have to take one on at some point in our writing careers. Personally, I don't believe that the novel is the right medium to conduct a crusade - political or social. Virginia Woolf said that we should never write fiction that encouraged one to 'write a cheque' or 'join a society', but that doesn't mean that we can't address political or social issues. Dickens revealed the horrors of the Victorian underworld, and Catherine Cookson wrote about 20th century prejudices against illegitimacy, class and colour - there are dozens more examples.

I have never, in my life, ever set out to write 'about' an 'issue' in anything but a feature article or media documentary. But my latest novel, The Centauress, tackles the very difficult subject of gender identity. Every year, one in every two thousand babies is born with some kind of gender anomaly. Some of these are quite small and may not get picked up unless there are problems with fertility or they have to take chromosome tests for international athletics. There are perfectly formed girls out there with XY genes. But it’s the physical manifestations that cause the most problems and, because all foetuses start out female and the Y chromosome is only triggered by a ‘wash’ of testosterone in the womb at about 6 weeks, variations in what we consider ‘the norm’ are common.

Historically cases of ‘indeterminate gender’ were usually solved by doing a bit of surgical trimming and bringing the child up as a girl. When I was researching the birth registers in Scotland to trace Catherine Cookson’s father I found an ‘Alexander Davies’ who seemed very promising - born in the right area at the right time with the right name. But when I looked at the register, the baby had been re-registered a few weeks later as a girl ‘Alexandra’. The registrar told me that it was not unusual.

A modern ‘gender assignment’ consultant explained what he called the ‘lop and chop option’ this way - ‘It’s always been easier to dig a hole than to put up a pole’. (The casual terminology made me shudder.) The creation of female genitalia was easier than its reverse and there was a belief among doctors that children were not actually gendered until the second year of their lives, so that if they were dressed in girl’s clothes and given dolls they would grow up to be (almost) perfectly normal young women.

In the USA there were a number of cases where for various reasons (some involving circumcision) babies with damaged penises were turned into girls. A consultant called John Money made research into these children his life’s work. But his belief that physical cosmetic surgery and cultural influence could make a boy into a girl or vice versa didn’t work out. Some of his patients suffered mental health problems, refused to conform, and some even reverted to the clothes and occupations of their original gender, though they had never been told what this was. It is only in the last 20 years that more research has been done into the gendering of the mind before birth - that we are male and female and all the shades in between before we even leave the womb. Plastic surgeons these days try to fit the body to the mind. This is very new and very controversial.

In some extreme cases, babies are born with the complete genitalia of both male and female. We call these hermaphrodites - the union of Hermes and Aphrodite. This has been well documented since written records began and there is a lot of art-work to confirm it too. Some of these drawings and paintings were in the records of ‘freak-shows’ and in 17th and 18th century erotica. But there is one beautiful marble carving (a copy of a Greek original) in the Louvre. It’s called ‘Sleeping Hermaphrodite’ and clearly shows the beautiful body of a woman with male genitalia.

Hermaphroditism has always interested me, since I was a young child of 8 or 9 and my uncle was divorcing his wife. My aunt had run off with another woman and it came up in court (a doctor gave evidence) that this ‘other woman’ was in fact a hermaphrodite. This scandal made the papers and, as children, we got quite used to finding the Sunday papers with holes where the adults had cut out the bits we weren’t supposed to read.

Later I read ‘Herculine Barbin’ - the memoirs of a 19th century woman brought up as a girl, but told when she was a teenager that she was a man. She couldn’t cope with the gender confusion and eventually committed suicide. It’s recently been re-issued edited by Michael Foucault.

Herculine Barbin 1868And then in Italy I met the sculptor Fiore de Henriquez, born a hermaphrodite in the years just after the first world war when attitudes to any kind of sexual difference were quite medieval. Fiore was quite open about her dual gender, talking about it freely - a most extraordinary woman with a huge personality - and someone I found utterly fascinating. She was the subject of a biography by my friend Jan Marsh - called ‘Art and Androgyny’ - and there's

a documentary film being made

about her life by US film maker Richard Whymark.

Herculine Barbin 1868And then in Italy I met the sculptor Fiore de Henriquez, born a hermaphrodite in the years just after the first world war when attitudes to any kind of sexual difference were quite medieval. Fiore was quite open about her dual gender, talking about it freely - a most extraordinary woman with a huge personality - and someone I found utterly fascinating. She was the subject of a biography by my friend Jan Marsh - called ‘Art and Androgyny’ - and there's

a documentary film being made

about her life by US film maker Richard Whymark.

When I wrote The Centauress , I didn’t set out to write a book about indeterminate gender. It was just that when the story formed in my head, one of the central dilemmas (and the tragedy) of the main character’s life was being born between sexes at a time when it wasn’t very well understood. As an adult woman, after the failure of her first serious love affair, Zenobia paints herself as an ambiguous Centauress - in Shakespeare’s words from King Lear, ‘Down from the waist they’re centaurs/Though women all above’. The figure of the Centauress was Zenobia’s image of the body she had been born with - neither one thing nor the other, but a merging of both.

Image of Centauress taken from Etruscan potteryIn the novel, my other main character, Alex, has to research this aspect of Zenobia’s life in order to understand why her life has been so turbulent and her relationships so chaotic. In particular, she needs to find out why Zenobia’s mother hated her so much. Their relationship had been mutually destructive, poisoned by blame and shame. Zenobia’s friend and companion, Concetta, tells Alex that ‘There is no hatred like that between a mother and daughter, because there are also such deep ties – it is a hatred that has roots that curl themselves around the heart and strangle it.’ But Zenobia’s mother had been unable to cope with the shame of giving birth to a child that was imperfect. It was a blow to her own femininity. Zenobia blames her mother for attempting to turn her into a ‘normal’ girl.

Image of Centauress taken from Etruscan potteryIn the novel, my other main character, Alex, has to research this aspect of Zenobia’s life in order to understand why her life has been so turbulent and her relationships so chaotic. In particular, she needs to find out why Zenobia’s mother hated her so much. Their relationship had been mutually destructive, poisoned by blame and shame. Zenobia’s friend and companion, Concetta, tells Alex that ‘There is no hatred like that between a mother and daughter, because there are also such deep ties – it is a hatred that has roots that curl themselves around the heart and strangle it.’ But Zenobia’s mother had been unable to cope with the shame of giving birth to a child that was imperfect. It was a blow to her own femininity. Zenobia blames her mother for attempting to turn her into a ‘normal’ girl.I grew up at a time when feminism was attempting to tell us that men and women were basically the same and that any admission of difference was to give substance to the argument that women were inferior because they were different from men. But I never believed that. We are different - we think differently and we have different skills. This should be valued, not denied. Tennyson (not exactly a feminist) once wrote that ‘there is no equality that does not take account of difference’ - and he was right. Gender difference is only one kind of difference used to put people down.

Anne Fausto-Sterling, Professor of Women's studies and Biology at Brown University, and author of The Five Sexes, writes about the complexities of gender very intelligently, if anyone wants to know more about the subject.

This novel has allowed me to think quite a lot about the way that writers and artists, both male and female think and work. We are conditioned to think in a binary way. My character Zenobia says proudly ‘I can see both sides, because, you see, I am both sides’. I like to believe that our different perspectives illuminate the whole; male and female and every shade in between, all together making one.

The Centauress was published on the 21st April and is available from Amazon.co.ukand from Amazon.com

The Centauress was published on the 21st April and is available from Amazon.co.ukand from Amazon.com"Bereaved biographer Alex Forbes goes to war-ravaged Croatia to research the life of celebrity artist Zenobia de Braganza and finds herself at the centre of a family conflict over a disputed inheritance. At the Kaštela Visoko Alex uncovers a mutilated photograph, stolen letters and a story of indeterminate gender, passion and betrayal. But can she believe what she is being told? In order to discover the truth about Zenobia, Alex travels to Istria, Venice, New York and London and, in working through the narrative of Zenobia’s life, Alex begins to make sense of her own and finds joy and love in a new relationship."

Published on May 10, 2014 06:35

May 6, 2014

Tuesday Poem: At Night in the House - Jean Sprackland

It's my turn to edit the main

Tuesday Poem blog

. If you don't know about the Tuesday Poem group, you might like to take a look - there are 28 of us from around the world and every Tuesday we try to post a poem on our own sites and take turns to edit the main hub. The idea originated in New Zealand and spread to Australia, America, Canada, the United Kingdom and Europe. We're a very diverse bunch!

My choice for the main hub today is a poem by

the UK poet Jean Sprackland -

winner of the Costa Award for poetry with her first collection 'Tilt' and nominated for all the major prizes since then. I like her poetry very much - particularly her latest collection 'Sleeping Keys'. I chose the poem At Night in the House because it gave me that shiver of recognition when I read it.

My choice for the main hub today is a poem by

the UK poet Jean Sprackland -

winner of the Costa Award for poetry with her first collection 'Tilt' and nominated for all the major prizes since then. I like her poetry very much - particularly her latest collection 'Sleeping Keys'. I chose the poem At Night in the House because it gave me that shiver of recognition when I read it.

At night in the house

a river runs through her

carrying its burdens

the golden barges the dead griefs and the quick fishes

She lies alone

wet at the mouth

and between the legs

and it runs not always placid

sometimes angry

rough as old rope

dragging its way

between the receding banks

the old wharves worn smooth

by all the moorings made there

the scrolled barges

with their forgotten cargoes

of sugar tobacco raw silk

and the illicit little night boats

tied up swiftly

while the moon was behind a cloud

the twelve slithery steps

cut into the dripping wall

When the river is running hard

she speaks only its own tongue

not the dry-docked language

of other people

and in places

the trees lean in

like conspirators

and the water is smeared

with whispers

and in places

the bank

melts into the water

roots and all

roots and all

even an unlucky heifer

risking the edge for a drink

In the night house

she is nothing but riverbanks

all she can feel is river

drawn through her

like a green rope

scouring the banks

with restlessness

hauled

towards open sea

taking its freight

of corpses

and drowned silverware.

Copyright Jean Sprackland - 'At Night in the House',

from Sleeping Keys

Jonathan Cape

With Permission

Why not click over to the Tuesday Poem blog to read my review of Sleeping Keys and find out what the other Tuesday Poets are posting?

My choice for the main hub today is a poem by

the UK poet Jean Sprackland -

winner of the Costa Award for poetry with her first collection 'Tilt' and nominated for all the major prizes since then. I like her poetry very much - particularly her latest collection 'Sleeping Keys'. I chose the poem At Night in the House because it gave me that shiver of recognition when I read it.

My choice for the main hub today is a poem by

the UK poet Jean Sprackland -

winner of the Costa Award for poetry with her first collection 'Tilt' and nominated for all the major prizes since then. I like her poetry very much - particularly her latest collection 'Sleeping Keys'. I chose the poem At Night in the House because it gave me that shiver of recognition when I read it. At night in the house

a river runs through her

carrying its burdens

the golden barges the dead griefs and the quick fishes

She lies alone

wet at the mouth

and between the legs

and it runs not always placid

sometimes angry

rough as old rope

dragging its way

between the receding banks

the old wharves worn smooth

by all the moorings made there

the scrolled barges

with their forgotten cargoes

of sugar tobacco raw silk

and the illicit little night boats

tied up swiftly

while the moon was behind a cloud

the twelve slithery steps

cut into the dripping wall

When the river is running hard

she speaks only its own tongue

not the dry-docked language

of other people

and in places

the trees lean in

like conspirators

and the water is smeared

with whispers

and in places

the bank

melts into the water

roots and all

roots and all

even an unlucky heifer

risking the edge for a drink

In the night house

she is nothing but riverbanks

all she can feel is river

drawn through her

like a green rope

scouring the banks

with restlessness

hauled

towards open sea

taking its freight

of corpses

and drowned silverware.

Copyright Jean Sprackland - 'At Night in the House',

from Sleeping Keys

Jonathan Cape

With Permission

Why not click over to the Tuesday Poem blog to read my review of Sleeping Keys and find out what the other Tuesday Poets are posting?

Published on May 06, 2014 04:37

May 4, 2014

Never refuse an adventure . . .

It's just light and my brain is still on the other side of Europe after a late arrival in Italy the night before, but the phone rings and it's an Italian friend who says - 'Such a beautiful day! Do you want to come sailing?' Do I want to? I love boats and the sea and rarely get the chance to indulge it (not being a boat owning oligarch - or even knowing one!).

The crew - none of them oligarchs . . .So the unopened suitcase got left on the bedroom floor and the bed was still unmade and the breakfast dishes unwashed. Neil swallowed the sea-sickness pills as we headed out for the boat mooring and we were soon tacking out of the La Bocca di Magra into the Mediterranean and a bit of a shock! Although it was a clear, calm day, once out of the river there was a very lively wind and a choppy sea that had us heeled over at a steep angle gazing down at the water and an almost horizontal sail. No photos - it's difficult to hold a camera when you're clinging to the wire with your feet wedged on the cabin.

The crew - none of them oligarchs . . .So the unopened suitcase got left on the bedroom floor and the bed was still unmade and the breakfast dishes unwashed. Neil swallowed the sea-sickness pills as we headed out for the boat mooring and we were soon tacking out of the La Bocca di Magra into the Mediterranean and a bit of a shock! Although it was a clear, calm day, once out of the river there was a very lively wind and a choppy sea that had us heeled over at a steep angle gazing down at the water and an almost horizontal sail. No photos - it's difficult to hold a camera when you're clinging to the wire with your feet wedged on the cabin.

This part of the Italian coast is called the Bay of the Poets - DH Lawrence and Byron both sailed it and now was not the time to remember that Shelley drowned here while sailing across! We moored in Lerici to eat our sandwiches on the dockside - just time for a quick look at the main square and then we sailed up to Porto Venere where we could turn round to catch the wind to go back the way we came.

Lerici on market dayThe wind died on the return trip and it was a very leisurely journey. I'm now absolutely knackered (as they say in Cumbria), but had a wonderful and totally unexpected day. Thank you Christian!

Lerici on market dayThe wind died on the return trip and it was a very leisurely journey. I'm now absolutely knackered (as they say in Cumbria), but had a wonderful and totally unexpected day. Thank you Christian!

The crew - none of them oligarchs . . .So the unopened suitcase got left on the bedroom floor and the bed was still unmade and the breakfast dishes unwashed. Neil swallowed the sea-sickness pills as we headed out for the boat mooring and we were soon tacking out of the La Bocca di Magra into the Mediterranean and a bit of a shock! Although it was a clear, calm day, once out of the river there was a very lively wind and a choppy sea that had us heeled over at a steep angle gazing down at the water and an almost horizontal sail. No photos - it's difficult to hold a camera when you're clinging to the wire with your feet wedged on the cabin.

The crew - none of them oligarchs . . .So the unopened suitcase got left on the bedroom floor and the bed was still unmade and the breakfast dishes unwashed. Neil swallowed the sea-sickness pills as we headed out for the boat mooring and we were soon tacking out of the La Bocca di Magra into the Mediterranean and a bit of a shock! Although it was a clear, calm day, once out of the river there was a very lively wind and a choppy sea that had us heeled over at a steep angle gazing down at the water and an almost horizontal sail. No photos - it's difficult to hold a camera when you're clinging to the wire with your feet wedged on the cabin.

This part of the Italian coast is called the Bay of the Poets - DH Lawrence and Byron both sailed it and now was not the time to remember that Shelley drowned here while sailing across! We moored in Lerici to eat our sandwiches on the dockside - just time for a quick look at the main square and then we sailed up to Porto Venere where we could turn round to catch the wind to go back the way we came.

Lerici on market dayThe wind died on the return trip and it was a very leisurely journey. I'm now absolutely knackered (as they say in Cumbria), but had a wonderful and totally unexpected day. Thank you Christian!

Lerici on market dayThe wind died on the return trip and it was a very leisurely journey. I'm now absolutely knackered (as they say in Cumbria), but had a wonderful and totally unexpected day. Thank you Christian!

Published on May 04, 2014 14:27