Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 30

June 11, 2015

Leaving Haida Gwaii

I've been staying in a Bear Hunting Lodge - except that it's under new management who are rather more bear friendly. So it's not surprising that I bumped into a bear on an evening walk. I took my picnic supper about an hour's walk up the coast, to the mouth of the Tlell river, and ate it sitting on a piece of driftwood in the dunes facing the sea. As I turned around the spit to walk back along the river, I saw something move up the river bank into the trees which grow right down to the edge and thought it was a deer - there are a lot of them here and they're quite tame. Then I saw the tracks, coming from the dunes to the river, and realised that it was a bear. He had probably been sitting in the dunes munching the wild strawberries that grow there while I was eating my supper! My only regret is that I didn't get a good look at him - still can't say that I've seen a bear.

The location of the lodge (called Haida House) is a small hamlet called Tlell - halfway down the east coast of Graham Island, where the Tlell river goes into the sea. Tlell is quite remote - midway between Masset and Skidegate on the Yellowhead Highway (the only highway). It's a beautiful place, and the staff are mainly Haida. Allison, who serves us breakfast, brought her Haida ceremonial regalia in to show us.This consists of a woven spruce root hat and a button blanket. These have evolved from animal skin robes and are now traditionally black and red, decorated with buttons of mother of pearl or abalone.

Allison is Eagle clan, so her blanket has an eagle appliqued on the back.

Now is the sad part - because I have to leave and drive north to Masset where I'm catching a plane to Vancouver and then another to England. It's so beautiful and so peaceful I'm really going to miss it. I think I'm going to leave part of myself here - like scraps of wool on a barbed wire fence.

The location of the lodge (called Haida House) is a small hamlet called Tlell - halfway down the east coast of Graham Island, where the Tlell river goes into the sea. Tlell is quite remote - midway between Masset and Skidegate on the Yellowhead Highway (the only highway). It's a beautiful place, and the staff are mainly Haida. Allison, who serves us breakfast, brought her Haida ceremonial regalia in to show us.This consists of a woven spruce root hat and a button blanket. These have evolved from animal skin robes and are now traditionally black and red, decorated with buttons of mother of pearl or abalone.

Allison is Eagle clan, so her blanket has an eagle appliqued on the back.

Now is the sad part - because I have to leave and drive north to Masset where I'm catching a plane to Vancouver and then another to England. It's so beautiful and so peaceful I'm really going to miss it. I think I'm going to leave part of myself here - like scraps of wool on a barbed wire fence.

Published on June 11, 2015 23:25

June 9, 2015

The lost villages - and people - of Haida Gwaii

The Haida refer to it as 'The Great Dying'; an epidemic of small pox, brought by the Europeans, that in 1862 wiped out whole communities, particularly on the southern islands of the Gwaii. One of my goals in coming here was to try to get to some of these abandoned villages. The southern part of Haida Gwaii is now a nature reserve and, apart from a small airstrip and village at the top of Moresby Island, is not inhabited at all. I drove down the east coast of the northern island to the township of Skidegate and immediately started asking how I could get into the south. The BandB I was staying in said that they were taking a group by boat the following day and would I like to join them? Would I! The weather wasn't good, but it would have taken a small army to keep me from going!

We went out in a Zodiac, all kitted out in waterproofs and flotation jackets, with a Haida crew, for a ride that was about 2 hours or more south in the turbulent waters of Hecate Strait, heading for Skedans - whose Haida name is K'aanu. So many people died here at one time that there was no one left to bury the dead and no one else dared approach the island in case of infection. Even today, visitors to the island come across bones on the forest floor that have to be reverently covered over.

These villages are heritage sites and you can't go unaccompanied. There are watchmen at every location - young people who volunteer for 2 week shifts, without any kind of mod cons, in a hut, to guard their history. At Skedans it was two girls. They said they weren't afraid of the bears or the storms, but had found the 'powerful energy' of the place very hard to get used to.

The Watch Hut with its radio mastOne of the Haida men who had come on the boat was the son of a hereditary chief of the clan and he told us his childhood memories and how his father had often brought him back there on camping trips, showing him the old places and telling him the stories of his clan. He was able to tell us what each of the House Poles meant and who had lived in the various houses, now collapsed.

The Watch Hut with its radio mastOne of the Haida men who had come on the boat was the son of a hereditary chief of the clan and he told us his childhood memories and how his father had often brought him back there on camping trips, showing him the old places and telling him the stories of his clan. He was able to tell us what each of the House Poles meant and who had lived in the various houses, now collapsed.

All that remains of one of the biggest houses which was called 'Sound of the Clouds Rowing Across the Sky'The poles are all precarious and rotting now - the thought is that in 20 years none of them will be there, so I am very privileged to have seen them at all. The air was full of the sound of woodpeckers drilling the wood.

All that remains of one of the biggest houses which was called 'Sound of the Clouds Rowing Across the Sky'The poles are all precarious and rotting now - the thought is that in 20 years none of them will be there, so I am very privileged to have seen them at all. The air was full of the sound of woodpeckers drilling the wood.

Toppling slowlyJags told us that when he came with his father they often found caves where families had hidden their possessions, packed in cedar wood boxes, still intact, and once they had found a shaman's carved staff wedged in between rocks in the roof. All these objects are now in the museum.

Toppling slowlyJags told us that when he came with his father they often found caves where families had hidden their possessions, packed in cedar wood boxes, still intact, and once they had found a shaman's carved staff wedged in between rocks in the roof. All these objects are now in the museum.

You can just make out the carving underneath the mossThe Haida survivors grouped together in smaller and smaller communities until only two main groups were left, at Masset and Skidegate on the north island. By 1900 a population of almost 30,000 had been reduced to around 500.

You can just make out the carving underneath the mossThe Haida survivors grouped together in smaller and smaller communities until only two main groups were left, at Masset and Skidegate on the north island. By 1900 a population of almost 30,000 had been reduced to around 500.

On the beach at K'aanuIt was an exceptionally beautiful and lonely place. I found it very moving, just to be there. The return journey was more challenging - against a flood tide with a strong southerly wind in opposition. Arrived back in port wind-blown, wet, but strangely happy.

On the beach at K'aanuIt was an exceptionally beautiful and lonely place. I found it very moving, just to be there. The return journey was more challenging - against a flood tide with a strong southerly wind in opposition. Arrived back in port wind-blown, wet, but strangely happy.

We went out in a Zodiac, all kitted out in waterproofs and flotation jackets, with a Haida crew, for a ride that was about 2 hours or more south in the turbulent waters of Hecate Strait, heading for Skedans - whose Haida name is K'aanu. So many people died here at one time that there was no one left to bury the dead and no one else dared approach the island in case of infection. Even today, visitors to the island come across bones on the forest floor that have to be reverently covered over.

These villages are heritage sites and you can't go unaccompanied. There are watchmen at every location - young people who volunteer for 2 week shifts, without any kind of mod cons, in a hut, to guard their history. At Skedans it was two girls. They said they weren't afraid of the bears or the storms, but had found the 'powerful energy' of the place very hard to get used to.

The Watch Hut with its radio mastOne of the Haida men who had come on the boat was the son of a hereditary chief of the clan and he told us his childhood memories and how his father had often brought him back there on camping trips, showing him the old places and telling him the stories of his clan. He was able to tell us what each of the House Poles meant and who had lived in the various houses, now collapsed.

The Watch Hut with its radio mastOne of the Haida men who had come on the boat was the son of a hereditary chief of the clan and he told us his childhood memories and how his father had often brought him back there on camping trips, showing him the old places and telling him the stories of his clan. He was able to tell us what each of the House Poles meant and who had lived in the various houses, now collapsed. All that remains of one of the biggest houses which was called 'Sound of the Clouds Rowing Across the Sky'The poles are all precarious and rotting now - the thought is that in 20 years none of them will be there, so I am very privileged to have seen them at all. The air was full of the sound of woodpeckers drilling the wood.

All that remains of one of the biggest houses which was called 'Sound of the Clouds Rowing Across the Sky'The poles are all precarious and rotting now - the thought is that in 20 years none of them will be there, so I am very privileged to have seen them at all. The air was full of the sound of woodpeckers drilling the wood. Toppling slowlyJags told us that when he came with his father they often found caves where families had hidden their possessions, packed in cedar wood boxes, still intact, and once they had found a shaman's carved staff wedged in between rocks in the roof. All these objects are now in the museum.

Toppling slowlyJags told us that when he came with his father they often found caves where families had hidden their possessions, packed in cedar wood boxes, still intact, and once they had found a shaman's carved staff wedged in between rocks in the roof. All these objects are now in the museum.  You can just make out the carving underneath the mossThe Haida survivors grouped together in smaller and smaller communities until only two main groups were left, at Masset and Skidegate on the north island. By 1900 a population of almost 30,000 had been reduced to around 500.

You can just make out the carving underneath the mossThe Haida survivors grouped together in smaller and smaller communities until only two main groups were left, at Masset and Skidegate on the north island. By 1900 a population of almost 30,000 had been reduced to around 500. On the beach at K'aanuIt was an exceptionally beautiful and lonely place. I found it very moving, just to be there. The return journey was more challenging - against a flood tide with a strong southerly wind in opposition. Arrived back in port wind-blown, wet, but strangely happy.

On the beach at K'aanuIt was an exceptionally beautiful and lonely place. I found it very moving, just to be there. The return journey was more challenging - against a flood tide with a strong southerly wind in opposition. Arrived back in port wind-blown, wet, but strangely happy.

Published on June 09, 2015 23:09

June 6, 2015

On the Edge of the World

So, after driving for twenty odd kilometers on a dirt road and then walking some, I'm finally standing on The Edge of the World. And this is what it looks like:

That's the Pacific ocean in front of me - the largest mass of water on the planet, and somewhere to the north of the picture is Alaska and the North Pole. It doesn't get much wilder than this.

I'm on North Beach looking towards Rose Spit - the most northerly point of Haida Gwaii - the place where Raven discovered human beings hiding in a giant clam shell and tempted them out because he was bored and wanted something to play with. Things have never been the same since!

Raven perching on the clam shell: Bill ReidIt's a very long walk up North Beach to Rose Spit, and you can really only do it when the tide is low - 24 kilometers each way. I was lucky enough to get a lift with one of the clam-diggers on the beach - a Haida fisherman called Randy driving a beat-up old pickup truck.

Raven perching on the clam shell: Bill ReidIt's a very long walk up North Beach to Rose Spit, and you can really only do it when the tide is low - 24 kilometers each way. I was lucky enough to get a lift with one of the clam-diggers on the beach - a Haida fisherman called Randy driving a beat-up old pickup truck.

Randy, driving down North Beach to beat the tide.I bounced around with the razor clams in the back.

Randy, driving down North Beach to beat the tide.I bounced around with the razor clams in the back.

He took me as far as he could go, driving on the beach with the tide coming in, and said I had about an hour to walk further up before he'd have to take me back. It was wild and beautiful and I did a bit of beach combing before going back to the truck.

a crab arranging itself for the photograph

a crab arranging itself for the photograph

A deer's hoofprint in the sandRandy was wearing a silver whale pendant as the mark of his clan group.

A deer's hoofprint in the sandRandy was wearing a silver whale pendant as the mark of his clan group.

'I was born and raised here,' he said, making a gesture with his hand. 'This is my place.'

It was said simply, but it felt very powerful. I wondered what it must feel like to belong somewhere in that way. To look at a landscape and know that your ancestors have been there for ten thousand years, that all your stories are grounded in it, that everything you see has a meaning, explicitly for you. We're such itinerants in Europe; most of us have no idea what that kind of rootedness feels like.

It was difficult to leave the beach - the most truly wild place I've found since I arrived here. Randy dropped me two or three kilometers from the road out and accelerated off to beat the tide and get his clams to market before they closed.

That's the Pacific ocean in front of me - the largest mass of water on the planet, and somewhere to the north of the picture is Alaska and the North Pole. It doesn't get much wilder than this.

I'm on North Beach looking towards Rose Spit - the most northerly point of Haida Gwaii - the place where Raven discovered human beings hiding in a giant clam shell and tempted them out because he was bored and wanted something to play with. Things have never been the same since!

Raven perching on the clam shell: Bill ReidIt's a very long walk up North Beach to Rose Spit, and you can really only do it when the tide is low - 24 kilometers each way. I was lucky enough to get a lift with one of the clam-diggers on the beach - a Haida fisherman called Randy driving a beat-up old pickup truck.

Raven perching on the clam shell: Bill ReidIt's a very long walk up North Beach to Rose Spit, and you can really only do it when the tide is low - 24 kilometers each way. I was lucky enough to get a lift with one of the clam-diggers on the beach - a Haida fisherman called Randy driving a beat-up old pickup truck. Randy, driving down North Beach to beat the tide.I bounced around with the razor clams in the back.

Randy, driving down North Beach to beat the tide.I bounced around with the razor clams in the back.

He took me as far as he could go, driving on the beach with the tide coming in, and said I had about an hour to walk further up before he'd have to take me back. It was wild and beautiful and I did a bit of beach combing before going back to the truck.

a crab arranging itself for the photograph

a crab arranging itself for the photograph A deer's hoofprint in the sandRandy was wearing a silver whale pendant as the mark of his clan group.

A deer's hoofprint in the sandRandy was wearing a silver whale pendant as the mark of his clan group. 'I was born and raised here,' he said, making a gesture with his hand. 'This is my place.'

It was said simply, but it felt very powerful. I wondered what it must feel like to belong somewhere in that way. To look at a landscape and know that your ancestors have been there for ten thousand years, that all your stories are grounded in it, that everything you see has a meaning, explicitly for you. We're such itinerants in Europe; most of us have no idea what that kind of rootedness feels like.

It was difficult to leave the beach - the most truly wild place I've found since I arrived here. Randy dropped me two or three kilometers from the road out and accelerated off to beat the tide and get his clams to market before they closed.

Published on June 06, 2015 15:30

June 5, 2015

The Totems of Old Massett

Well, apart from sleeping in Margaret Atwood's bed and having my breakfast cooked for me, what I've really come to see here are the remnants of Haida culture at the northern end of the northernmost island. The Haida seem to have been one of the most successful First Nation people in preserving their traditions, though it was touch and go - not long ago there were only 5 native Haida speakers left alive. But Haida artists in particular have kept the artistic traditions going and are handing the skills down to younger generations. One of them is

Jim Hart, one of Canada's

most distinguished artists, a descendant of the wonderful Haida sculptor Charles Edenshaw, and also a hereditary Haida chief. Jim's son danced a traditional Haida dance at the opening of the Emily Carr exhibition in London last year. Jim is currently carving a new project, with his apprentices, here in Masset. I couldn't photograph the work in progress, but I can let you see the massive cedar trunk waiting its turn on the banks of Masset inlet, underneath Jim's Eagle totem. The tree really is huge - almost as wide as I'm tall.

Once, the whole of the shore was lined with totems in Masset, house poles and mortuary poles fronting the Haida longhouses.

Now there are fewer, scattered through the village, but gradually creeping back.

Painted Haida house and pole

Painted Haida house and pole

Totem on the street - you can see the hooked beak of the eagle near the bottom.

Totem on the street - you can see the hooked beak of the eagle near the bottom.

There are ravens and eagles everywhere in Masset - so it's easy to see how the two main clan divisions of the Haida became established. Ravens are easy to photograph - the eagles are more difficult because they're usually high in the sky or roosting on the tops of trees. If you're Haida you're either Raven or Eagle and traditionally you can't marry someone from your own clan. Raven at Masset InletOne of my tasks here has been to consult the Council of the Haida Nation for permission to write about them and reference their stories and myths. Unlike other cultures, stories in Haida Gwaii are owned by particular families and handed down from generation to generation - I suppose it's a form of copyright. So I need permission to quote certain stories, and as a matter of respect, I need permission to publish photographs of their artefacts. The local head of the council here - a woman - was very kind and businesslike and will put my request in front of the cultural committee.

Raven at Masset InletOne of my tasks here has been to consult the Council of the Haida Nation for permission to write about them and reference their stories and myths. Unlike other cultures, stories in Haida Gwaii are owned by particular families and handed down from generation to generation - I suppose it's a form of copyright. So I need permission to quote certain stories, and as a matter of respect, I need permission to publish photographs of their artefacts. The local head of the council here - a woman - was very kind and businesslike and will put my request in front of the cultural committee.

While indigenous culture here is doing better than in many other places I've visited, there is still a lot of poverty and inequality. There are two villages - Masset (which is largely European) and Old Masset (which is largely Haida). Masset appears to be thriving, but Old Masset is a mixture of extreme poverty - abandoned cars and neglected buildings among the houses of the more prosperous Haida. One of the run-down houses on the waterfront.

One of the run-down houses on the waterfront.

The old museum, now abandoned. There are no shops that I could find - the big supermarkets are in Masset, and - though I looked for somewhere that might sell Haida artwork or carvings, I didn't see any, though I know there are some in Masset. Perhaps tourists don't usually go to Old Masset. That was definitely my impression.

The old museum, now abandoned. There are no shops that I could find - the big supermarkets are in Masset, and - though I looked for somewhere that might sell Haida artwork or carvings, I didn't see any, though I know there are some in Masset. Perhaps tourists don't usually go to Old Masset. That was definitely my impression.

Tomorrow I'm going out to explore the forests and the beaches, hoping that the weather, which has become overcast and rather gloomy, will improve a little. But I really shouldn't be wishing for the sun - they're desperate for rain here, having had dry sunny weather and high temperatures for almost a month - unheard of! No one here questions climate change and the Haida, like other First Nation people in Canada are at the forefront of environmental action. There are NoEnbridge signs in front gardens signalling opposition to the trans Canada pipeline that is supposed to transport oil from the Alberta tar sands to a tanker port on the coast too near Haida Gwaii for safety. In the Masset coffee shop there's a poster warning of the Fukishima radiation turning up on the beaches here - as a Haida saying has it 'Everything is connected' - what we do in one part of the world affects everyone else.

Once, the whole of the shore was lined with totems in Masset, house poles and mortuary poles fronting the Haida longhouses.

Now there are fewer, scattered through the village, but gradually creeping back.

Painted Haida house and pole

Painted Haida house and pole Totem on the street - you can see the hooked beak of the eagle near the bottom.

Totem on the street - you can see the hooked beak of the eagle near the bottom.

There are ravens and eagles everywhere in Masset - so it's easy to see how the two main clan divisions of the Haida became established. Ravens are easy to photograph - the eagles are more difficult because they're usually high in the sky or roosting on the tops of trees. If you're Haida you're either Raven or Eagle and traditionally you can't marry someone from your own clan.

Raven at Masset InletOne of my tasks here has been to consult the Council of the Haida Nation for permission to write about them and reference their stories and myths. Unlike other cultures, stories in Haida Gwaii are owned by particular families and handed down from generation to generation - I suppose it's a form of copyright. So I need permission to quote certain stories, and as a matter of respect, I need permission to publish photographs of their artefacts. The local head of the council here - a woman - was very kind and businesslike and will put my request in front of the cultural committee.

Raven at Masset InletOne of my tasks here has been to consult the Council of the Haida Nation for permission to write about them and reference their stories and myths. Unlike other cultures, stories in Haida Gwaii are owned by particular families and handed down from generation to generation - I suppose it's a form of copyright. So I need permission to quote certain stories, and as a matter of respect, I need permission to publish photographs of their artefacts. The local head of the council here - a woman - was very kind and businesslike and will put my request in front of the cultural committee. While indigenous culture here is doing better than in many other places I've visited, there is still a lot of poverty and inequality. There are two villages - Masset (which is largely European) and Old Masset (which is largely Haida). Masset appears to be thriving, but Old Masset is a mixture of extreme poverty - abandoned cars and neglected buildings among the houses of the more prosperous Haida.

One of the run-down houses on the waterfront.

One of the run-down houses on the waterfront. The old museum, now abandoned. There are no shops that I could find - the big supermarkets are in Masset, and - though I looked for somewhere that might sell Haida artwork or carvings, I didn't see any, though I know there are some in Masset. Perhaps tourists don't usually go to Old Masset. That was definitely my impression.

The old museum, now abandoned. There are no shops that I could find - the big supermarkets are in Masset, and - though I looked for somewhere that might sell Haida artwork or carvings, I didn't see any, though I know there are some in Masset. Perhaps tourists don't usually go to Old Masset. That was definitely my impression. Tomorrow I'm going out to explore the forests and the beaches, hoping that the weather, which has become overcast and rather gloomy, will improve a little. But I really shouldn't be wishing for the sun - they're desperate for rain here, having had dry sunny weather and high temperatures for almost a month - unheard of! No one here questions climate change and the Haida, like other First Nation people in Canada are at the forefront of environmental action. There are NoEnbridge signs in front gardens signalling opposition to the trans Canada pipeline that is supposed to transport oil from the Alberta tar sands to a tanker port on the coast too near Haida Gwaii for safety. In the Masset coffee shop there's a poster warning of the Fukishima radiation turning up on the beaches here - as a Haida saying has it 'Everything is connected' - what we do in one part of the world affects everyone else.

Published on June 05, 2015 15:30

June 3, 2015

In Margaret Atwood's Bedroom

So here I am, in Masset, Haida Gwaii, in Margaret Atwood's bedroom. I'm staying at the famous Copper Beech, where Margaret stayed when she was writing a book and, due to a wonderful coincidence, I've been given her bedroom, which is called 'The Retreat'. It's more like a ship's cabin than a room.

I was supposed to be in one of the others (they're all wonderful in their own way) but then the man who'd booked The Room arrived and he was too tall for the bed, so I offered to swap my Queen size for his Economy and here I am. It's small but perfectly formed and I have the view to die for between my toes at the end of the bed. The only problem is that I'm now expected to write something worthy of the room, which probably means that I won't write a word!

I was supposed to be in one of the others (they're all wonderful in their own way) but then the man who'd booked The Room arrived and he was too tall for the bed, so I offered to swap my Queen size for his Economy and here I am. It's small but perfectly formed and I have the view to die for between my toes at the end of the bed. The only problem is that I'm now expected to write something worthy of the room, which probably means that I won't write a word!

Boats moored in Masset Inlet at the bottom of my bed. Copper Beech is owned by Canadian poet

Susan Musgrave

and is one of the most interesting and quirky guest houses I've ever stayed in. It's like staying in the curiosity shop of some exotic bazaar. My bedroom has the most beautiful peacock silk embroidered curtains balanced on a bamboo pole (heaven forbid I should ever have to close them!), there's a bedside light made out of a bamboo teapot, a ceiling light made from a wheel, puppets dangling from antlers, a copper bowl full of stones, bones and feathers, and the walls are decorated with paintings and hangings by Haida artists. Raven is here in all his incarnations. All the rooms of the house are crowded with wonderful things. This is the sitting room, complete with African penis gourd and The Last Supper arranged in a sardine can.

Boats moored in Masset Inlet at the bottom of my bed. Copper Beech is owned by Canadian poet

Susan Musgrave

and is one of the most interesting and quirky guest houses I've ever stayed in. It's like staying in the curiosity shop of some exotic bazaar. My bedroom has the most beautiful peacock silk embroidered curtains balanced on a bamboo pole (heaven forbid I should ever have to close them!), there's a bedside light made out of a bamboo teapot, a ceiling light made from a wheel, puppets dangling from antlers, a copper bowl full of stones, bones and feathers, and the walls are decorated with paintings and hangings by Haida artists. Raven is here in all his incarnations. All the rooms of the house are crowded with wonderful things. This is the sitting room, complete with African penis gourd and The Last Supper arranged in a sardine can.

Copper Beech has a long history - it was originally owned by an island eccentric and was at one point a 1$ flop-house. Then the previous owner ran it as a B&B which was famous for impromptu dinners and excellent company as well as the outrageous decor. David Philips, something of a performance artist, played host to 'lost souls, hippies and celebrities like the Trudeaus'. Apparently if you stayed here you never knew quite what might happen, and you were just as likely to fall through the furniture as into it. Susan has changed the beds and the sofas in the interests of comfort, but the rest has been kept just as it was. This is the Haida carved chest in the sitting room, used as a coffee table.

The company is as varied as the house. There's a doctor and his fiancee who are walking the length of the island and have come to have their wedding rings made by a Haida jeweller. Two middle aged ladies have cycled (!!) all the way from Smithers in northern British Columbia, via Prince Rupert on the mainland, to get here. That's a journey of several hundred miles. There's a naturalist looking at the bird life and an academic from Victoria. Oh, and another writer - Katie Welch , who has written an eco-novel called The Bears.

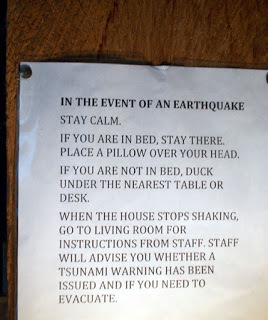

Just one note of caution - Haida Gwaii sits on the Queen Charlotte fault, which is very active. There's a notice on my bedroom wall fit to strike fear into the most valiant soul. In the event of an earthquake . . .

I was supposed to be in one of the others (they're all wonderful in their own way) but then the man who'd booked The Room arrived and he was too tall for the bed, so I offered to swap my Queen size for his Economy and here I am. It's small but perfectly formed and I have the view to die for between my toes at the end of the bed. The only problem is that I'm now expected to write something worthy of the room, which probably means that I won't write a word!

I was supposed to be in one of the others (they're all wonderful in their own way) but then the man who'd booked The Room arrived and he was too tall for the bed, so I offered to swap my Queen size for his Economy and here I am. It's small but perfectly formed and I have the view to die for between my toes at the end of the bed. The only problem is that I'm now expected to write something worthy of the room, which probably means that I won't write a word! Boats moored in Masset Inlet at the bottom of my bed. Copper Beech is owned by Canadian poet

Susan Musgrave

and is one of the most interesting and quirky guest houses I've ever stayed in. It's like staying in the curiosity shop of some exotic bazaar. My bedroom has the most beautiful peacock silk embroidered curtains balanced on a bamboo pole (heaven forbid I should ever have to close them!), there's a bedside light made out of a bamboo teapot, a ceiling light made from a wheel, puppets dangling from antlers, a copper bowl full of stones, bones and feathers, and the walls are decorated with paintings and hangings by Haida artists. Raven is here in all his incarnations. All the rooms of the house are crowded with wonderful things. This is the sitting room, complete with African penis gourd and The Last Supper arranged in a sardine can.

Boats moored in Masset Inlet at the bottom of my bed. Copper Beech is owned by Canadian poet

Susan Musgrave

and is one of the most interesting and quirky guest houses I've ever stayed in. It's like staying in the curiosity shop of some exotic bazaar. My bedroom has the most beautiful peacock silk embroidered curtains balanced on a bamboo pole (heaven forbid I should ever have to close them!), there's a bedside light made out of a bamboo teapot, a ceiling light made from a wheel, puppets dangling from antlers, a copper bowl full of stones, bones and feathers, and the walls are decorated with paintings and hangings by Haida artists. Raven is here in all his incarnations. All the rooms of the house are crowded with wonderful things. This is the sitting room, complete with African penis gourd and The Last Supper arranged in a sardine can.

Copper Beech has a long history - it was originally owned by an island eccentric and was at one point a 1$ flop-house. Then the previous owner ran it as a B&B which was famous for impromptu dinners and excellent company as well as the outrageous decor. David Philips, something of a performance artist, played host to 'lost souls, hippies and celebrities like the Trudeaus'. Apparently if you stayed here you never knew quite what might happen, and you were just as likely to fall through the furniture as into it. Susan has changed the beds and the sofas in the interests of comfort, but the rest has been kept just as it was. This is the Haida carved chest in the sitting room, used as a coffee table.

The company is as varied as the house. There's a doctor and his fiancee who are walking the length of the island and have come to have their wedding rings made by a Haida jeweller. Two middle aged ladies have cycled (!!) all the way from Smithers in northern British Columbia, via Prince Rupert on the mainland, to get here. That's a journey of several hundred miles. There's a naturalist looking at the bird life and an academic from Victoria. Oh, and another writer - Katie Welch , who has written an eco-novel called The Bears.

Just one note of caution - Haida Gwaii sits on the Queen Charlotte fault, which is very active. There's a notice on my bedroom wall fit to strike fear into the most valiant soul. In the event of an earthquake . . .

Published on June 03, 2015 15:30

June 1, 2015

Tuesday Poem: Da'Axiigang - Kathleen Jones

Da Axiigang - Charles Edenshaw

Haida sculptor

1849-1920

They couldn’t say his name

‘noise in the house-pit’

so they called him Charlie,

bought bracelets for their wives,

could not believe his skill

when he shaped bentwood, stone and silver

carving his family history

in narratives of animals and birds and fish

thought savage, but

appropriated anyway for

ethnographical

research, passed round

in after-dinner rooms with whisky and cigars

by tribal elders of colonial plunder

who couldn’t read the clicking

vowels and consonants scored

onto argillite, as smooth as mirror glass,

the totem whorls of language

they themselves had lost

but felt

the power of the telling

in the stories he spoke

with his hands.

© Kathleen Jones 2015

'Charles Edenshaw' carving a silver bracelet.Having posted last week about the way that the British tried to deprive the First Nation people of their language, and the confiscation of many of their sacred objects, regalia and other art work, I thought it might be appropriate to post this poem about one of the major artists of the Haida - a man the British renamed Charles Edenshaw. Recently there was a huge exhibition of his work in Vancouver, brought together from museums and galleries all over the world. His descendants still carry on the traditions and several are major artists themselves - Gwaii Edenshaw, Robert Davidson, to name only two.

'Charles Edenshaw' carving a silver bracelet.Having posted last week about the way that the British tried to deprive the First Nation people of their language, and the confiscation of many of their sacred objects, regalia and other art work, I thought it might be appropriate to post this poem about one of the major artists of the Haida - a man the British renamed Charles Edenshaw. Recently there was a huge exhibition of his work in Vancouver, brought together from museums and galleries all over the world. His descendants still carry on the traditions and several are major artists themselves - Gwaii Edenshaw, Robert Davidson, to name only two. The Tuesday Poets are an international group who try to post a poem every Tuesday and take it in turns to edit the main hub. If you'd like to see what the other Tuesday poets are posting, please click this link.

The Tuesday Poets are an international group who try to post a poem every Tuesday and take it in turns to edit the main hub. If you'd like to see what the other Tuesday poets are posting, please click this link.

Published on June 01, 2015 15:30

Gator Gardens - a small paradise on Cormorant Island

I'm sitting in the middle of a swamp on the top of a hill overlooking a stretch of the Inner Passage between the mainland of British Columbia and Vancouver Island.

Officially, this nature reserve is called the Ecological Park, but the locals call it 'Gator Gardens' - originally a joke, but the name stuck. There isn't an alligator for hundreds of miles, only the kronk of ravens and the hunting cries of the bald eagles overhead.

The swamp was created when the company that owned the fish cannery down in the bay below dammed the freshwater supply to service the factory. It backed up the springs at the top of the island, creating a huge boggy area and killing the big cedars that grew there. The cannery has gone long ago, but the community decided to keep the ecological disaster and turn it into a park. The result is a place of great beauty. The dead trunks are hundreds of feet high.

It's unbelievably peaceful - all I can hear is bird song - woodpeckers, ravens, herons, eagles, and other birds I can't identify.

It's unbelievably peaceful - all I can hear is bird song - woodpeckers, ravens, herons, eagles, and other birds I can't identify.

Most of the trees that still have foliage are draped in the lichen they call 'Witches Hair' here.

I've been enjoying being able to walk. The island's shoreline is very beautiful - the beaches are piled with boulder and tree trunks from the winter storms and there are stunning views across to other islands and the mainland.

I love the old buildings here.

Someone has collected three old doubledecker buses. One of them even has Morecambe as a destination - there must be someone else here who comes from Cumbria!

But at the heart of the island there is a blank space - a large stretch of newly seeded grass.

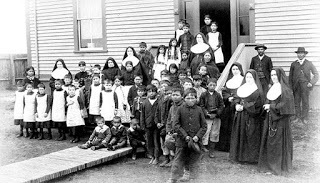

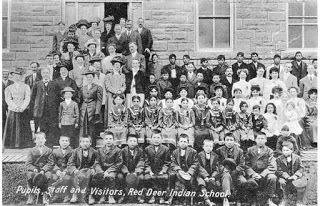

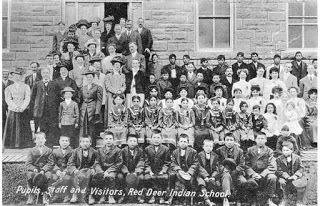

This is the site of the old St Michaels Residential School - one of the biggest of the 'schools of sorrow' - where hundreds of First Nation children were sent to be 'educated' throughout the twentieth century. This is what it looked like in recent times - a gigantic structure, dwarfing the tiny single or double storey buildings on the island.

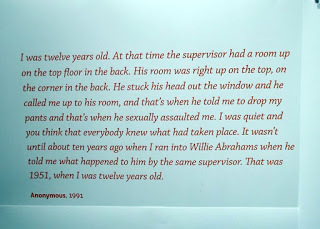

It was closed down about 20 years ago and remained empty until it was decided to give it to the Namgis first Nation People, on whose land it had been built. The Namgis performed ritual cleansing of the building and then, only a couple of months ago, it was bulldozed down and the ground cleared. The museum has first hand testimonies from children who were educated there - many of them quite harrowing accounts. In the cemetery, there's a Haida mortuary pole to commemorate all the Haida children who died in St Michaels.

It was closed down about 20 years ago and remained empty until it was decided to give it to the Namgis first Nation People, on whose land it had been built. The Namgis performed ritual cleansing of the building and then, only a couple of months ago, it was bulldozed down and the ground cleared. The museum has first hand testimonies from children who were educated there - many of them quite harrowing accounts. In the cemetery, there's a Haida mortuary pole to commemorate all the Haida children who died in St Michaels.

The view now, is one of serenity.

Tomorrow I'm leaving this paradise to make my way up to Haida Gwaii - a long, long way north. Feeling a bit nervous - it's been my dream for such a long time and it's such a long way to travel. Fingers crossed!

Officially, this nature reserve is called the Ecological Park, but the locals call it 'Gator Gardens' - originally a joke, but the name stuck. There isn't an alligator for hundreds of miles, only the kronk of ravens and the hunting cries of the bald eagles overhead.

The swamp was created when the company that owned the fish cannery down in the bay below dammed the freshwater supply to service the factory. It backed up the springs at the top of the island, creating a huge boggy area and killing the big cedars that grew there. The cannery has gone long ago, but the community decided to keep the ecological disaster and turn it into a park. The result is a place of great beauty. The dead trunks are hundreds of feet high.

It's unbelievably peaceful - all I can hear is bird song - woodpeckers, ravens, herons, eagles, and other birds I can't identify.

It's unbelievably peaceful - all I can hear is bird song - woodpeckers, ravens, herons, eagles, and other birds I can't identify.

Most of the trees that still have foliage are draped in the lichen they call 'Witches Hair' here.

I've been enjoying being able to walk. The island's shoreline is very beautiful - the beaches are piled with boulder and tree trunks from the winter storms and there are stunning views across to other islands and the mainland.

I love the old buildings here.

Someone has collected three old doubledecker buses. One of them even has Morecambe as a destination - there must be someone else here who comes from Cumbria!

But at the heart of the island there is a blank space - a large stretch of newly seeded grass.

This is the site of the old St Michaels Residential School - one of the biggest of the 'schools of sorrow' - where hundreds of First Nation children were sent to be 'educated' throughout the twentieth century. This is what it looked like in recent times - a gigantic structure, dwarfing the tiny single or double storey buildings on the island.

It was closed down about 20 years ago and remained empty until it was decided to give it to the Namgis first Nation People, on whose land it had been built. The Namgis performed ritual cleansing of the building and then, only a couple of months ago, it was bulldozed down and the ground cleared. The museum has first hand testimonies from children who were educated there - many of them quite harrowing accounts. In the cemetery, there's a Haida mortuary pole to commemorate all the Haida children who died in St Michaels.

It was closed down about 20 years ago and remained empty until it was decided to give it to the Namgis first Nation People, on whose land it had been built. The Namgis performed ritual cleansing of the building and then, only a couple of months ago, it was bulldozed down and the ground cleared. The museum has first hand testimonies from children who were educated there - many of them quite harrowing accounts. In the cemetery, there's a Haida mortuary pole to commemorate all the Haida children who died in St Michaels.

The view now, is one of serenity.

Tomorrow I'm leaving this paradise to make my way up to Haida Gwaii - a long, long way north. Feeling a bit nervous - it's been my dream for such a long time and it's such a long way to travel. Fingers crossed!

Published on June 01, 2015 05:00

May 31, 2015

The Totems of Alert Bay

I took the Greyhound north out of Victoria, for nine hours up the east coast of Vancouver Island to a little harbour called Port McNeill where I hopped onto a ferry for Cormorant Island.

The journey took me all day but I finally arrived in Alert Bay about 12 hours after I left Victoria. Cormorant Island is the home of the Namgis tribe, who are part of the Kwakwaka' wakw people, whose art work I looked at in the Museum of Anthropology while I was in Vancouver.

The journey took me all day but I finally arrived in Alert Bay about 12 hours after I left Victoria. Cormorant Island is the home of the Namgis tribe, who are part of the Kwakwaka' wakw people, whose art work I looked at in the Museum of Anthropology while I was in Vancouver.

My distant island destinationI'm staying at the Seine Boat Inn - a wooden waterfront construction with its feet in the sea.

My distant island destinationI'm staying at the Seine Boat Inn - a wooden waterfront construction with its feet in the sea.

You listen to the ocean lapping underneath the floor all night and it's very soothing - just like being on a boat. Everything's made of wood, but utterly immaculate and the beds are a glorious, sinking experience - all kept by Colin, who emigrated here from Britain when he was 17 and hasn't felt like going back since.

You can keep an eye out for Orca while you have breakfast.It's very cosmopolitan here - there are quite a few Americans, the cafe over the street is run by a couple from India, there are several Korean fishermen, Chinese store-keepers and quite a lot of Brits. But it's the First Nation residents I've come to meet. On my first evening, taking a quick walk along the shoreline to shake the journey out of my legs before I went to bed, I came across an old cemetery with fallen totems.

You can keep an eye out for Orca while you have breakfast.It's very cosmopolitan here - there are quite a few Americans, the cafe over the street is run by a couple from India, there are several Korean fishermen, Chinese store-keepers and quite a lot of Brits. But it's the First Nation residents I've come to meet. On my first evening, taking a quick walk along the shoreline to shake the journey out of my legs before I went to bed, I came across an old cemetery with fallen totems.

The following day someone explained to me that they don't maintain these memorials. They believe in a natural cycle of life, decay and death; everything has its allotted time, so when the totems fall they're allowed to rot back into the ground.

There's a museum now in Alert Bay -called U'mista, which means 'that which was given back'. The museum is built in the style of the traditional 'Big House'.

And the museum contains all the precious objects and ceremonial regalia that was taken away from the Namgis at the beginning of the twentieth century, when their ceremonies and celebrations were forbidden. Most of it went to museums, or to private collectors, and a surprising amount (given how tightly they hold on to their acquisitions) has now been returned. I was allowed to photograph the mask below, but the others are too sacred.

The most important ceremony for First Nation people was the Potlatch - a big party to celebrate a community event, but which also passed on important cultural knowledge, stories, songs, and tribal history to younger generations - often in the form of dancing with masks and robes, dancers acting out the traditional legends. It was also part of the Potlatch for the family to give away personal wealth to the guests in the form of gifts. This is how the tradition was summed up by one of the tribal elders.

"When one's heart is glad, he gives away gifts. It was given to us by our Creator, to be our way of doing things, to be our way of rejoicing, we who are Indian. The Potlatch was given to us to be our way of expressing joy!" [Grandmother Agnes Alfred, community leader, Alert Bay]

Needless to say, the colonial authorities weren't happy with this and Potlatches were banned - participants being liable to imprisonment. All the ceremonial regalia, robes and masks, dishes, banners and tribal emblems, was taken off to go to museums or to be sold to private collectors.

After I'd been to the museum - I went up to the top of the hill to see the tallest totem pole in the world and the Namgis' Big House, where they celebrate their contemporary Potlatches. The tallest totem pole proved too tall to photograph!

The Chief's house has a housepole outside with his lineage on it. Part of it is an Orca with a man on its back.

Alert Bay is a strange little place, sitting astride two communities. At the end of May it's still not summer here and many places were still closed for winter. Some also had For Sale signs outside.

A fishing boat leaving harbour earlyIt has the feeling of a place on the edge of something. There's very little money here now - the days of the 'million dollar catch' are gone and the fishing is thin, but it's either that or logging and most people divide their time between the two.

A fishing boat leaving harbour earlyIt has the feeling of a place on the edge of something. There's very little money here now - the days of the 'million dollar catch' are gone and the fishing is thin, but it's either that or logging and most people divide their time between the two.

A big fish cannery that was built along the shore has long since fallen into the sea, and there are notices all along the harbour warning not to catch mussels, clams or oysters since they're all contaminated with 'Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning'. This comes from algal blooms in the Pacific, which used to be rare, but have become more frequent.

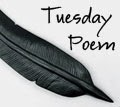

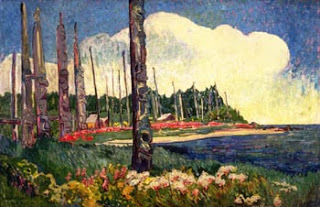

Emily Carr once came here to paint the totems that lined the bay and the painted war canoes pulled up on the shore.

Emily Carr: 'War Canoes at Alert Bay'Now there are fewer totems, but I did spot one canoe poking its nose out of a shed, being repainted for summer.

Emily Carr: 'War Canoes at Alert Bay'Now there are fewer totems, but I did spot one canoe poking its nose out of a shed, being repainted for summer.

The journey took me all day but I finally arrived in Alert Bay about 12 hours after I left Victoria. Cormorant Island is the home of the Namgis tribe, who are part of the Kwakwaka' wakw people, whose art work I looked at in the Museum of Anthropology while I was in Vancouver.

The journey took me all day but I finally arrived in Alert Bay about 12 hours after I left Victoria. Cormorant Island is the home of the Namgis tribe, who are part of the Kwakwaka' wakw people, whose art work I looked at in the Museum of Anthropology while I was in Vancouver. My distant island destinationI'm staying at the Seine Boat Inn - a wooden waterfront construction with its feet in the sea.

My distant island destinationI'm staying at the Seine Boat Inn - a wooden waterfront construction with its feet in the sea.

You listen to the ocean lapping underneath the floor all night and it's very soothing - just like being on a boat. Everything's made of wood, but utterly immaculate and the beds are a glorious, sinking experience - all kept by Colin, who emigrated here from Britain when he was 17 and hasn't felt like going back since.

You can keep an eye out for Orca while you have breakfast.It's very cosmopolitan here - there are quite a few Americans, the cafe over the street is run by a couple from India, there are several Korean fishermen, Chinese store-keepers and quite a lot of Brits. But it's the First Nation residents I've come to meet. On my first evening, taking a quick walk along the shoreline to shake the journey out of my legs before I went to bed, I came across an old cemetery with fallen totems.

You can keep an eye out for Orca while you have breakfast.It's very cosmopolitan here - there are quite a few Americans, the cafe over the street is run by a couple from India, there are several Korean fishermen, Chinese store-keepers and quite a lot of Brits. But it's the First Nation residents I've come to meet. On my first evening, taking a quick walk along the shoreline to shake the journey out of my legs before I went to bed, I came across an old cemetery with fallen totems.

The following day someone explained to me that they don't maintain these memorials. They believe in a natural cycle of life, decay and death; everything has its allotted time, so when the totems fall they're allowed to rot back into the ground.

There's a museum now in Alert Bay -called U'mista, which means 'that which was given back'. The museum is built in the style of the traditional 'Big House'.

And the museum contains all the precious objects and ceremonial regalia that was taken away from the Namgis at the beginning of the twentieth century, when their ceremonies and celebrations were forbidden. Most of it went to museums, or to private collectors, and a surprising amount (given how tightly they hold on to their acquisitions) has now been returned. I was allowed to photograph the mask below, but the others are too sacred.

The most important ceremony for First Nation people was the Potlatch - a big party to celebrate a community event, but which also passed on important cultural knowledge, stories, songs, and tribal history to younger generations - often in the form of dancing with masks and robes, dancers acting out the traditional legends. It was also part of the Potlatch for the family to give away personal wealth to the guests in the form of gifts. This is how the tradition was summed up by one of the tribal elders.

"When one's heart is glad, he gives away gifts. It was given to us by our Creator, to be our way of doing things, to be our way of rejoicing, we who are Indian. The Potlatch was given to us to be our way of expressing joy!" [Grandmother Agnes Alfred, community leader, Alert Bay]

Needless to say, the colonial authorities weren't happy with this and Potlatches were banned - participants being liable to imprisonment. All the ceremonial regalia, robes and masks, dishes, banners and tribal emblems, was taken off to go to museums or to be sold to private collectors.

After I'd been to the museum - I went up to the top of the hill to see the tallest totem pole in the world and the Namgis' Big House, where they celebrate their contemporary Potlatches. The tallest totem pole proved too tall to photograph!

The Chief's house has a housepole outside with his lineage on it. Part of it is an Orca with a man on its back.

Alert Bay is a strange little place, sitting astride two communities. At the end of May it's still not summer here and many places were still closed for winter. Some also had For Sale signs outside.

A fishing boat leaving harbour earlyIt has the feeling of a place on the edge of something. There's very little money here now - the days of the 'million dollar catch' are gone and the fishing is thin, but it's either that or logging and most people divide their time between the two.

A fishing boat leaving harbour earlyIt has the feeling of a place on the edge of something. There's very little money here now - the days of the 'million dollar catch' are gone and the fishing is thin, but it's either that or logging and most people divide their time between the two.

A big fish cannery that was built along the shore has long since fallen into the sea, and there are notices all along the harbour warning not to catch mussels, clams or oysters since they're all contaminated with 'Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning'. This comes from algal blooms in the Pacific, which used to be rare, but have become more frequent.

Emily Carr once came here to paint the totems that lined the bay and the painted war canoes pulled up on the shore.

Emily Carr: 'War Canoes at Alert Bay'Now there are fewer totems, but I did spot one canoe poking its nose out of a shed, being repainted for summer.

Emily Carr: 'War Canoes at Alert Bay'Now there are fewer totems, but I did spot one canoe poking its nose out of a shed, being repainted for summer.

Published on May 31, 2015 10:21

May 29, 2015

Emily Carr's House in Victoria

Emily Carr is one of Canada's most famous artists and her distinctive work was exhibited in England only a few months ago at the Dulwich Art Gallery, called 'Between the Forest and the Sea'. I've been fascinated by Emily ever since a friend lent me the Susan Vreeland novel '

The Forest Lover'

based on her life, so one of the things I wanted to do here was to find her home. Emily was born in a newly developing Victoria, in 1871 - the year that British Columbia was incorporated into Canada. Her parents had come from Kent, England, by way of California. Emily's father was a successful businessman who had a store, and built a substantial house on 8 acres of land hacked out of the forest. Emily made fun of his desire to recreate a little England in Canada. 'Father had buried a tremendous homesickness in this new soil and it had rooted and sprung up English'. The house still stands, as elegant as it ever was. It's now a museum dedicated to Emily.

The Carrs were an important part of the city community. The street used to be called Carr St, but is now Government St, because the Parliament building stands on the corner of it.

Emily Carr, the youngest of 5 sisters, was an unusual child. From an early age she refused to conform. She described the moment when her name was inscribed in the family bible with her baby brother's, like this: 'The covers of the Bible banged, shutting us all in.' Her early life was hemmed in by religion. She complained that her sisters were so prudish they had to wear bathing suits when they took a bath and even then, only in a darkened room!

Emily is wearing the lace collar.When she was only a young teenager Emily's mother died, probably from tuberculosis, and her father followed 2 years later, leaving Emily under the guardianship of her eldest sister. There was a great deal of friction. Mr Carr had allowed Emily to have art lessons and cherish hopes of a career in art, but now she had to fight for what she wanted, sometimes consulting the family trustee in order to persuade her sisters to let her go to San Francisco, or Paris, or London in pursuit of her studies. There were a lot of arguments in these parlours.

Emily is wearing the lace collar.When she was only a young teenager Emily's mother died, probably from tuberculosis, and her father followed 2 years later, leaving Emily under the guardianship of her eldest sister. There was a great deal of friction. Mr Carr had allowed Emily to have art lessons and cherish hopes of a career in art, but now she had to fight for what she wanted, sometimes consulting the family trustee in order to persuade her sisters to let her go to San Francisco, or Paris, or London in pursuit of her studies. There were a lot of arguments in these parlours.

The rooms have been wallpapered with the original designs chosen by the Carr family and are filled with the fussy details of 19th century colonial life. Immigrants even had their pianos shipped the thousands of miles round Cape Horn.

Emily, stifled by the life she was forced to lead in respectable Victoria, became fascinated by First Nation art. She found a couple willing to take her to the remote islands by boat and spent months camping out in order to paint the decaying totem poles, villages and other relics of the culture that was being gradually eroded. It is now a very important record of a vanished world.

But her paintings didn't sell, so Emily spent her inheritance to build a lodging house so that she could live off the rent. It still stands, just round the corner from the Carr house. She hated being a landlady.

Emily gave up painting for 15 years because she was so discouraged. But, after a chance meeting with other artists, she took up her paintbrush again and this time her work was more in tune with the public mood. After an exhibition of Canadian art at the Tate Gallery in London, in 1938, the art critic of the Manchester Guardian described her as 'a genius'.

Her health declined through the late thirties and she developed a heart condition. Advised to take life easily, she began to write and her memoirs and journals are as brilliant as her paintings. I'm currently reading her journals, published after her death in 1945, called 'Hundreds and Thousands'. She once told a would-be biographer 'No one is going to tell my hotch-potch life, but me!'

Emily's typewriter and a photograph of her as a child.She died in a nursing home, just along the street from her childhood home. It's now a guest house called the James Bay Inn.

Emily's typewriter and a photograph of her as a child.She died in a nursing home, just along the street from her childhood home. It's now a guest house called the James Bay Inn.

The Carrs were an important part of the city community. The street used to be called Carr St, but is now Government St, because the Parliament building stands on the corner of it.

Emily Carr, the youngest of 5 sisters, was an unusual child. From an early age she refused to conform. She described the moment when her name was inscribed in the family bible with her baby brother's, like this: 'The covers of the Bible banged, shutting us all in.' Her early life was hemmed in by religion. She complained that her sisters were so prudish they had to wear bathing suits when they took a bath and even then, only in a darkened room!

Emily is wearing the lace collar.When she was only a young teenager Emily's mother died, probably from tuberculosis, and her father followed 2 years later, leaving Emily under the guardianship of her eldest sister. There was a great deal of friction. Mr Carr had allowed Emily to have art lessons and cherish hopes of a career in art, but now she had to fight for what she wanted, sometimes consulting the family trustee in order to persuade her sisters to let her go to San Francisco, or Paris, or London in pursuit of her studies. There were a lot of arguments in these parlours.

Emily is wearing the lace collar.When she was only a young teenager Emily's mother died, probably from tuberculosis, and her father followed 2 years later, leaving Emily under the guardianship of her eldest sister. There was a great deal of friction. Mr Carr had allowed Emily to have art lessons and cherish hopes of a career in art, but now she had to fight for what she wanted, sometimes consulting the family trustee in order to persuade her sisters to let her go to San Francisco, or Paris, or London in pursuit of her studies. There were a lot of arguments in these parlours.

The rooms have been wallpapered with the original designs chosen by the Carr family and are filled with the fussy details of 19th century colonial life. Immigrants even had their pianos shipped the thousands of miles round Cape Horn.

Emily, stifled by the life she was forced to lead in respectable Victoria, became fascinated by First Nation art. She found a couple willing to take her to the remote islands by boat and spent months camping out in order to paint the decaying totem poles, villages and other relics of the culture that was being gradually eroded. It is now a very important record of a vanished world.

But her paintings didn't sell, so Emily spent her inheritance to build a lodging house so that she could live off the rent. It still stands, just round the corner from the Carr house. She hated being a landlady.

Emily gave up painting for 15 years because she was so discouraged. But, after a chance meeting with other artists, she took up her paintbrush again and this time her work was more in tune with the public mood. After an exhibition of Canadian art at the Tate Gallery in London, in 1938, the art critic of the Manchester Guardian described her as 'a genius'.

Her health declined through the late thirties and she developed a heart condition. Advised to take life easily, she began to write and her memoirs and journals are as brilliant as her paintings. I'm currently reading her journals, published after her death in 1945, called 'Hundreds and Thousands'. She once told a would-be biographer 'No one is going to tell my hotch-potch life, but me!'

Emily's typewriter and a photograph of her as a child.She died in a nursing home, just along the street from her childhood home. It's now a guest house called the James Bay Inn.

Emily's typewriter and a photograph of her as a child.She died in a nursing home, just along the street from her childhood home. It's now a guest house called the James Bay Inn.

Published on May 29, 2015 21:51

May 28, 2015

Victoria and the Schools of Sorrow

I stood in the middle of the British Columbia Museum and wept. I was reading the human history of the west coast lands, now known as British Columbia, and when I came to the period when the British began to 'colonise and consolidate' the land that Captain Cook and his lieutenant Vancouver had claimed, it was almost unbearable.

When they arrived the land was already inhabited; and when British Columbia was annexed as Crown Territory there were still three indigenous people to every British immigrant. Our justification was that - according to the first Commissioner for Land - the 'Indians' had no right to the land because 'they can put no value on it' and it had 'no utility for them'. The ideology was that unless you can put a price on something or turn it into profit, you have no right to have it. Because the First Nation people did not exploit or cultivate the land and because land ownership was a totally alien concept, their land rights were simply taken away to be given 'to some industrious people' eg the British invaders. What happened next has been referred to as genocide, but it was a complex process.

The exhibition I was looking at in the Museum, is called 'Living Language' and is placed at the centre of their permanent exhibition of the human history of the territory. British Columbia once had more indigenous languages than any other country. One or two of these languages have no relationship to any other language on earth - they are totally unique. And so are the concepts that these languages express. The word Put 'lt for instance, means 'everything belongs to those not yet born' - a phrase you'd think that the colonialists should have listened to. The indigenous people also believed that their language came from the land and was inextricably connected to it. It also connects with their history. One native speaker said to me, 'It is an invisible line from the heart into the past'.

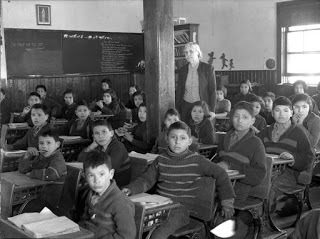

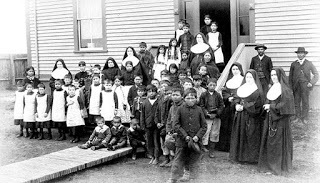

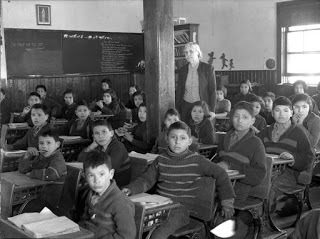

The great power of language to connect people and communities to each other and to their land is demonstrated by the great lengths that the British Colonial authorities were prepared to go to separate the indigenous people from those languages. To achieve assimilation and Europeanisation, the Canadian government worked with the churches to create and administer Residential Schools for First Nation children.

The openly avowed intention was 'to kill the Indian in the child' - but in many cases it also killed the child. The death rate was around 40%, but attendance was mandatory for all children aged 5-15. 'Indian Agents' and the Police forcibly removed children from their homes and arrested parents who resisted.

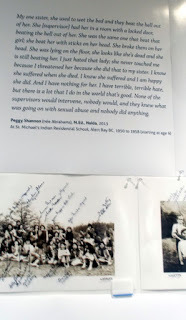

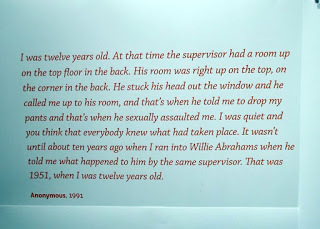

These schools were known as 'the Schools of Sorrow'. The speaking of aboriginal languages was banned, and the personal testimonies of survivors (more than 50,000 children died) makes grim reading. They were subjected to abuse; physical, sexual and psychological. They were under-clothed, under-fed, ill-treated, and subjected to excessive, often sadistic, corporal punishment. Many are now deaf or suffer eye and breathing defects because they were repeatedly hit over the head. Some lost limbs from frost-bite from being shut outside in winter as a punishment. They can now claim compensation, but no amount of money can ever compensate for what they suffered then and still suffer now.

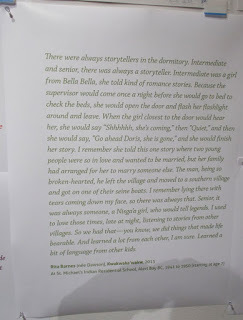

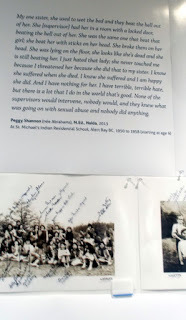

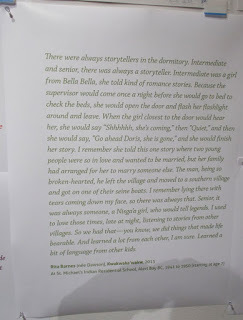

Many of the children refused to be broken. Two little boys stole a rowing boat and managed to row to another island. There's a heart-breaking exhibit of two keys made from sardine tin openers that were made by enterprising children to break into the school's locked food stores. And there was also, among all the terrible testimony, the underlining of the power of story-telling. In every dormitory there was always one child who would risk punishment to tell the traditional stories and keep them alive. 'There were always storytellers', this woman says.

Many of the children refused to be broken. Two little boys stole a rowing boat and managed to row to another island. There's a heart-breaking exhibit of two keys made from sardine tin openers that were made by enterprising children to break into the school's locked food stores. And there was also, among all the terrible testimony, the underlining of the power of story-telling. In every dormitory there was always one child who would risk punishment to tell the traditional stories and keep them alive. 'There were always storytellers', this woman says.

This is not in the distant past - the last school was closed in 1996.

Now you know why I was weeping. And I haven't told you some of the worst things because they are unbearable. That supposedly civilised people purporting to have Christian values could perpetrate such cruelty is hard to believe. But we did and must shoulder some of the moral responsibility. In 2008 the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, apologised, alongside the churches and representatives of the Police.

Unbearable testimony, but it needs to be heard. Against all the odds, the First Nation people managed to hold on to the shreds of their culture and their languages and are beginning to rebuild, through a process of what is called 'Truth and Reconciliation'. Some First Nation people have even managed to regain the land that was never legally ceded in the first place. But it's taken a long time and a lot of fighting through the courts. It's interesting that the ones who are rebuilding most successfully are those who managed to hang on to their language - a language in which their identity, their values and their culture is embedded.

Unbearable testimony, but it needs to be heard. Against all the odds, the First Nation people managed to hold on to the shreds of their culture and their languages and are beginning to rebuild, through a process of what is called 'Truth and Reconciliation'. Some First Nation people have even managed to regain the land that was never legally ceded in the first place. But it's taken a long time and a lot of fighting through the courts. It's interesting that the ones who are rebuilding most successfully are those who managed to hang on to their language - a language in which their identity, their values and their culture is embedded.

We don't deserve it, but there is considerable forgiveness and a reaching out. This is the fabulous Haida musician Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson performing a traditional Haida Peace-making song which she will be singing in a concert in Vancouver this weekend.

When they arrived the land was already inhabited; and when British Columbia was annexed as Crown Territory there were still three indigenous people to every British immigrant. Our justification was that - according to the first Commissioner for Land - the 'Indians' had no right to the land because 'they can put no value on it' and it had 'no utility for them'. The ideology was that unless you can put a price on something or turn it into profit, you have no right to have it. Because the First Nation people did not exploit or cultivate the land and because land ownership was a totally alien concept, their land rights were simply taken away to be given 'to some industrious people' eg the British invaders. What happened next has been referred to as genocide, but it was a complex process.

The exhibition I was looking at in the Museum, is called 'Living Language' and is placed at the centre of their permanent exhibition of the human history of the territory. British Columbia once had more indigenous languages than any other country. One or two of these languages have no relationship to any other language on earth - they are totally unique. And so are the concepts that these languages express. The word Put 'lt for instance, means 'everything belongs to those not yet born' - a phrase you'd think that the colonialists should have listened to. The indigenous people also believed that their language came from the land and was inextricably connected to it. It also connects with their history. One native speaker said to me, 'It is an invisible line from the heart into the past'.

The great power of language to connect people and communities to each other and to their land is demonstrated by the great lengths that the British Colonial authorities were prepared to go to separate the indigenous people from those languages. To achieve assimilation and Europeanisation, the Canadian government worked with the churches to create and administer Residential Schools for First Nation children.

The openly avowed intention was 'to kill the Indian in the child' - but in many cases it also killed the child. The death rate was around 40%, but attendance was mandatory for all children aged 5-15. 'Indian Agents' and the Police forcibly removed children from their homes and arrested parents who resisted.

These schools were known as 'the Schools of Sorrow'. The speaking of aboriginal languages was banned, and the personal testimonies of survivors (more than 50,000 children died) makes grim reading. They were subjected to abuse; physical, sexual and psychological. They were under-clothed, under-fed, ill-treated, and subjected to excessive, often sadistic, corporal punishment. Many are now deaf or suffer eye and breathing defects because they were repeatedly hit over the head. Some lost limbs from frost-bite from being shut outside in winter as a punishment. They can now claim compensation, but no amount of money can ever compensate for what they suffered then and still suffer now.

Many of the children refused to be broken. Two little boys stole a rowing boat and managed to row to another island. There's a heart-breaking exhibit of two keys made from sardine tin openers that were made by enterprising children to break into the school's locked food stores. And there was also, among all the terrible testimony, the underlining of the power of story-telling. In every dormitory there was always one child who would risk punishment to tell the traditional stories and keep them alive. 'There were always storytellers', this woman says.

Many of the children refused to be broken. Two little boys stole a rowing boat and managed to row to another island. There's a heart-breaking exhibit of two keys made from sardine tin openers that were made by enterprising children to break into the school's locked food stores. And there was also, among all the terrible testimony, the underlining of the power of story-telling. In every dormitory there was always one child who would risk punishment to tell the traditional stories and keep them alive. 'There were always storytellers', this woman says.

This is not in the distant past - the last school was closed in 1996.

Now you know why I was weeping. And I haven't told you some of the worst things because they are unbearable. That supposedly civilised people purporting to have Christian values could perpetrate such cruelty is hard to believe. But we did and must shoulder some of the moral responsibility. In 2008 the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, apologised, alongside the churches and representatives of the Police.

Unbearable testimony, but it needs to be heard. Against all the odds, the First Nation people managed to hold on to the shreds of their culture and their languages and are beginning to rebuild, through a process of what is called 'Truth and Reconciliation'. Some First Nation people have even managed to regain the land that was never legally ceded in the first place. But it's taken a long time and a lot of fighting through the courts. It's interesting that the ones who are rebuilding most successfully are those who managed to hang on to their language - a language in which their identity, their values and their culture is embedded.

Unbearable testimony, but it needs to be heard. Against all the odds, the First Nation people managed to hold on to the shreds of their culture and their languages and are beginning to rebuild, through a process of what is called 'Truth and Reconciliation'. Some First Nation people have even managed to regain the land that was never legally ceded in the first place. But it's taken a long time and a lot of fighting through the courts. It's interesting that the ones who are rebuilding most successfully are those who managed to hang on to their language - a language in which their identity, their values and their culture is embedded.We don't deserve it, but there is considerable forgiveness and a reaching out. This is the fabulous Haida musician Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson performing a traditional Haida Peace-making song which she will be singing in a concert in Vancouver this weekend.

Published on May 28, 2015 21:55