Preston Lewis's Blog, page 9

April 3, 2015

Liberty Valance

As a young boy I remember seeing a lot of John Wayne movies in the 1960s, but one I don’t recall is The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I do remember the identically named Gene Pitney song, though it was not actually used in the picture. If I did see the movie, it probably didn’t strike me at the time as it was filmed in black and white and didn’t have the grand Technicolor landscapes that were such an integral part of the westerns I recall.

Lee Marvin, Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne

But now that I’ve had the opportunity to watch it multiple times on TCM, I consider it one of the best western movies ever made because of its stark black-and-white portrayal of good versus evil and, at the same time, its nuanced view of myth and reality in the Old West as articulated by newspaper editor Maxwell Scott’s line, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

With screen giants John Wayne as rancher Tom Doniphon, Jimmy Stewart as newly arrived eastern lawyer Ransom Stoddard and Lee Marvin as the delicious villain Liberty Valance, the film was loaded with star power, but the character actors were equally delightful. They included Andy Devine as the atypical portly and nervous town marshal, Strother Martin as Valance’s delightfully obsequious sidekick, and Edmond O’Brien as Dutton Peabody, the pompous and tipsy editor of the Shinbone Star.

One of my favorite move exchanges ever, again because of its juxtaposition of myth and reality, is journalist Peabody’s protest against his nomination to a political post.

Peabody (O’Brien): Good people of Shinbone, I, I’m your conscience; I’m the small voice that thunders in the night; I’m your watchdog, who howls against the wolves. I, I’m your father confessor! I, I’m … what else am I?

Doniphon (Wayne): Town drunk?

In many ways, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is an elegy to the passing of the Old West, the conflict between the past as represented by both Doniphon and Valance and the future as represented by Stoddard, whose gunfight with Valance wins him the girl, Vera Miles in this case, and ultimately earns him a seat in the U.S. Senate. One of John Wayne’s most powerful acting scenes, ranking right up there with some of his scenes in The Searchers, comes when he explains what really happened the night Liberty Valance died. All was not as it seemed that night, and reputations were made and lost as a result.

Directed by John Ford, The Many Who Shot Liberty Valance is considered by some critics as one of the first revisionist westerns because it upended the traditional cliché of the mano-a-mano showdown. If it is indeed a revisionist western, it is one with more heart and less bile than in most revisionist westerns.

The film was added to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2007 because of its cultural significance. It’s worth seeing again.

March 25, 2015

A New Acquaintance

One of the things I enjoy about history is getting to meet such interesting people. In researching Civil War journalism for a talk as part of Angelo State University’s Civil War Lecture Series this week, I first met Peter Wellington Alexander. I was drawn to him because modern historians have called him the Confederacy’s Ernie Pyle, one of my early writing influences.

Peter W. Alexander

Alexander wrote primarily for the ironically named Savannah Republican during the Civil War. A University of Georgia graduate with a degree in English, he became one of the most literate and respected of all Civil War reporters. He strove for the truth and was committed to improving the plight of the common soldier, thus earning him the Ernie Pyle sobriquet.

His newspaper dispatches stand the test of time, providing evocative detail of life and death on the battlefield and reflecting the ever changing fortunes of the Confederacy he covered. After the battle of First Bull Run, Alexander sent a telegram to his newspaper: “Glory to God in the highest!” he began, then dictated his story with the lead “A great battle has been fought and victory won!”

At Antietam after the bloodiest day in American history, Alexander wrote “There is a smell of death in the air, and the laboring surgeons are literally covered from head to foot with the blood of the sufferers.”

After Antietam he wrote of the soldiers’ dire straits, initiating a campaign of public contributions to assist the boys in gray. “The Army has not had a mouthful of bread for four days, and no food of any kind except a little green corn picked up in the roadside for 36 hours. Many of them also are barefooted. I have seen scores of them today marching over the flinty turnpike with torn and blistered feet. They bear these hardships without murmuring. … Men may fight with clubs, with bows, with stones, with their hands, but they cannot fight and march without shoes.”

He was so beloved by the soldiers that when he was rumored to be reassigned to his newspaper’s office, soldiers in one Georgia regiment volunteered to give a dollar a man out of their $13 a month pay to keep him at the front.

Alexander was at the Battle of Gettysburg, providing the best Southern account of the pivotal battle. Alexander is distinctive in that his initial reports of the Pennsylvania encounter questioned Gen. Lee’s decisions and tactics on both the second and third days of the battle. His were the first such printed criticisms of Lee, whose actions at Gettysburg are still debated to this day.

After the war, Alexander remained in journalism but devoted much of his free time to collecting Civil War papers and accounts for posterity. His correspondence and documents make up major resources at both Columbia University and the University of Arkansas. I am attracted to his story because of both his journalistic excellence and commitment to preserving history.

March 18, 2015

Lomax Is Back

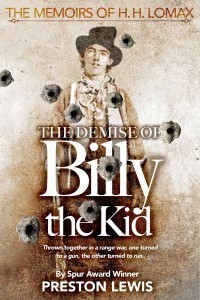

Working Cover

For an author, seeing one of your books return to print is like running into an old friend that you haven’t seen for years. So, I am excited to see the return of The Memoirs of H.H. Lomax, starting this summer. I wrote three books in this series in the mid-1990s, and the first of those, The Demise of Billy the Kid, is on schedule for re-publication this summer. I just got the initial look at the new cover for Demise and am well pleased.

Back in the early 1990s, I was approached by Bantam and Book Creations Inc. to develop an offbeat character that just happened to create a mess wherever he went in the Old West. Thus, was born H.H. Lomax, my favorite character of all those I have created over the years. Lomax was distinctive enough to actually get a mention in the Wall Street Journal when he first appeared on the publishing scene.

In line with the publisher’s request to put him in the middle of things, Lomax wound up being tailed by Billy the Kid the night the outlaw died. Lomax rode with Jesse James on his first bank robbery and actually knocked the picture askew that Jesse was straightening the day he was shot in the back. And, after Lomax became the first person in literary history to have a tooth pulled by the notorious frontier dentist Doc Holliday, he—not Doc—actually fired the first shot at the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

Implausible? Not according to Lomax, who recounts his adventures in his own cynical voice in his memoirs. I am in the process of researching the Battle of Little Bighorn so Lomax’s adventures can continue after the first three books in the series are reprinted. All I can say is watch out General Custer!

So, welcome back Lomax! The new book cover marks your return and a continuation of your offbeat western adventures.

March 16, 2015

Games Writers Play

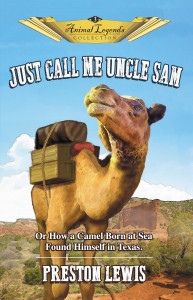

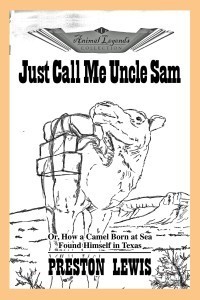

I’ve now received an electronic version of the finished cover of my next juvenile book, Just Call Me Uncle Sam. That’s when I finally feel like I’ve actually published a book, even though it won’t be available for awhile.

This’ll be book No. 27 published under my name and various pseudonyms. I’ve written four others that remain unpublished, though I actually got paid for two of those. Two publishers (Doubleday and HarperCollins) signed and paid me for books, then decided they were dropping their western or historical lines before my books were published. Shows you my impact on publishing!

This’ll be book No. 27 published under my name and various pseudonyms. I’ve written four others that remain unpublished, though I actually got paid for two of those. Two publishers (Doubleday and HarperCollins) signed and paid me for books, then decided they were dropping their western or historical lines before my books were published. Shows you my impact on publishing!

So far Just Call Me Uncle Sam has gotten rave reviews from the sole person other than me and the editors to read it, our oldest granddaughter Hannah, who got tired of waiting for it to appear in print. So, for Christmas I gave her a spiral bound copy of the manuscript. She loved it, especially the lines she, her sister Miriam and her cousins Cora and Carys gave me to include in the book!

During a summer visit to San Angelo, I asked each of the girls to come up with a line that a horse might say to a camel, since The Grands were really into horses. The two oldest, Hannah and Cora, came up with “Why do you have a mountain on your back?” and “Why do you have such big feet?” Pretty good lines, don’t you think? At three- and two-years-old, respectively, the younger two came up with more challenging lines. Miriam offered “No, no, no” and Carys presented “Hay, hay, hay” or was it “Hey, hey, hey”?

Anyway, I named four fillies—Hannah Horse, Miriam Horse, Cora Colt and Carys Colt—in the book for The Grands and managed to work their lines into the narrative. It’s the type of things writers do to amuse themselves and to bring a smile to their granddaughters’ faces.

March 12, 2015

Writing Influences: Mark Twain

Christmas Gift 1960

For Christmas in 1960, my Aunt Ella Mae and Uncle Joe Whitworth gave me a copy of Huckleberry Finn. To my recollection that was my first exposure to Mark Twain, the last of the three writers I would say influenced my writing ambitions as a youth.

Since I didn’t have a large personal library then, I read that copy of Huckleberry Finn multiple times before I went off to college. Additionally, I visited the school and public libraries to check out other of Twain’s works, including Tom Sawyer, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Life on the Mississippi and Roughing It.

My aunt and uncle were not literary people and of all the books they could have given me that Christmas I have always wondered why my aunt gave me what is considered by many to be the greatest American novel ever written. Maybe it was because the title character spent a lot of time on the Mississippi River. My parents, the Whitworths and my brother and I as kids spent a lot of leisure time fishing on the Llano and later Pecos rivers. Whatever the reason for selecting that book, it gave me a juvenile appreciation of Mark Twain as a storyteller.

After high school and college I gained a more sophisticated appreciation of Twain as an American humorist and novelist from a few biographies and critical essays I read. What I enjoyed most about Twain was his timeless insight into the foibles and fallibilities of humanity. His observations about the human condition in the 19th Century still ring true in the 21st Century.

My favorite Mark Twain quote is: “Get your facts first, and then you can distort ’em as much as you please.” That observation seems to accurately represent the state of American politics and national journalism today.

I purchased a magnet with that quotation at the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut, a couple years ago when we visited New England. I keep the magnet on our refrigerator as a reminder of the house tour where I stood in the actual room where Twain wrote Huckleberry Finn.

What I enjoy about Twain is that his works can be read on multiple levels. Further, his words and his observations remain timeless, such as “Against the assault of laughter nothing can stand.” Or how about his observation on health and fitness, “The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d druther not.”

Mark Twain, you’ve gotta love him, his literature and, most of all, his perpetual insight.

March 7, 2015

Cover Art

When painters or sculptors finish their artistic endeavors, they have something to display. When writers finish a project, they have a stack of typewritten pages, nothing they can frame for the wall or display on a coffee table.

When painters or sculptors finish their artistic endeavors, they have something to display. When writers finish a project, they have a stack of typewritten pages, nothing they can frame for the wall or display on a coffee table.

That’s why it is always nice for a writer to see what the publisher is planning for the cover art for a completed manuscript. The cover art is confirmation that all the work you did months earlier will finally bear fruit.

I just received the rough for my next young adult novel, Just Call Me Uncle Sam. The book covers the adventures of a camel born at sea on his way to Texas as part of a pre-Civil War experiment to see if camels were a good fit for the Army in the American Southwest.

Just Call Me Uncle Sam will be out later this spring from Wild Horse Press.

March 5, 2015

Writing Influences: Ernie Pyle

Probably the most influential writer in my life was Ernie Pyle, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and war correspondent for Scripps-Howard. Of course, he died at the end of World War II before my birth, but I could find his collected works of WWII newspaper columns in the Pease Elementary library when I was in grade school.

Ernie Pyle’s Typewriter

I recall reading Here Is Your War and Brave Men, but I don’t remember if the grade school library had Ernie Pyle in England and Last Chapter. After I left college, I found copies of all four in used bookstores and purchased them for my personal library, reading or re-reading each one.

Until I read Pyle, I never realized you could make a living by writing. That realization started me on the road to a journalism education, beginning my career with four Texas newspapers before moving into higher education communications. Pyle was a fine writer, as are many others who have worked in newspapers, but he had an uncommon empathy for the common man in his reporting.

That compassion, rendered into ink on newsprint, made him a favorite of both those fighting the war and those back home starved for details of their loved ones overseas. He wrote with such humility that reading him was like hearing from a lifelong friend with news of common acquaintances.

Pyle is best remembered for his Pulitzer Prize-winning column on the death of Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas, in the mountains of Italy. “Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules,” he wrote, then reported how each man from Waskow’s unit offered his respect, including one who silently held the dead captain’s hand for five minutes before gently straightening the deceased’s shirt collar and walking away and back into the war.

Another poignant account is of his stroll along Omaha Beach the day after the Longest Day. “It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore. Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever.” He then described “the awful waste and destruction of war” by simply noting the debris on the beach. Pyle died like many of the men he covered, killed by machine gun fire on the Okinawan island of Ie Shima on April 18, 1945.

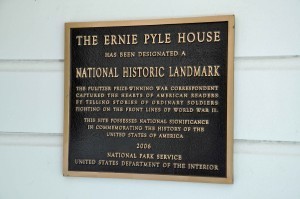

National Honor

I have been fortunate to visit both his home, which is now a National Historic Landmark that serves as a branch of the Albuquerque Public Library, and his grave in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at the Punchbowl in Honolulu. I own his four WWII books as well as Home Country, a collection of the Depression-era stories he wrote about Americans during hard times. By the penciled prices on the inside of each cover, I know I paid only $6.95 for all five books. Their value to me as examples of good writing, often under deadline and length constraints, has greatly exceeded their cost.

February 27, 2015

Writing Influences: J. Frank Dobie

Writing is a solitary occupation, just you and the blank screen or, before word processors, the blank page. Some would say reading is solitary as well, but I would disagree because you get to meet such interesting people, either the authors themselves or their subjects, through the printed or electronic pages they produce.

Consequently, most writers have an authors’ tree, much like a family tree, of individuals who have influenced or nurtured their writing careers by example, if nothing else, across decades or even centuries. For me, there were three such writing influences. The first was J. Frank Dobie, an American folklorist and writer, who taught English for many years at the University of Texas. He is credited by many for saving the Texas Longhorn as a breed.

While I can’t confirm that with certainty, what I can say is his book The Longhorns was one of the most memorable I ever read. Growing up in West Texas, I was always close to the state’s ranching heritage, but it was The Longhorns that fleshed out that history and fired my love of the Old West. I remember checking The Longhorns out of the library at Pease Elementary and devouring it. He saved the lore of the cowboy and the cattle drive for posterity.

Though many have written about the cowboy era, no one else has done it as well nor with the same authority and authenticity as Dobie. He was a born storyteller, who respected the work of the common laborer, which was basically what the cowboy was in the frontier era. Dobie preserved their stories and legends so that schoolboys like me could ride with the cowboys of old without ever leaving our bedrooms. My interest in writing about the Old West sprang from reading all the Dobie books I could check out of the elementary school library, including The Mustangs and Coronado’s Children, a collection of tales about lost mines and treasures of the West.

Later, I read his stories in True West, and one of my proudest writing moments was following in his footsteps and having some of my articles published in True West as well, including one, “Bluster’s Last Stand,” which won a Spur Award. The Longhorns marked my first exposure to Old Blue, Charles Goodnight’s famous lead steer, which I later wrote about in my young adult novel They Call Me Old Blue.

For his writing and folklorist career, President Lyndon Johnson in the fall of 1964 awarded Dobie the Medal of Freedom. Four days later on September 18, Dobie died. Though his voice was stilled a half century ago, his words live on and to this day hold an honored place on my bookshelves.