Preston Lewis's Blog, page 5

January 20, 2018

Writing Insights

Like many folks, I’ve been a fan of Peanuts for as long as I can remember because of the wonderful characters and the understated philosophical insights into life that Charles Schulz provided on a daily basis for half a century.

There’s an old adage in writing that it is harder to write short than long, best stated by Mark Twain in correspondence to  a friend when he said he would’ve written a short letter, but he didn’t have the time. Good writing in short packages is the biggest challenge of all, yet Schulz did it on a daily basis for 50 years. Not only that, he also illustrated and captioned each panel he did for the newspapers.

a friend when he said he would’ve written a short letter, but he didn’t have the time. Good writing in short packages is the biggest challenge of all, yet Schulz did it on a daily basis for 50 years. Not only that, he also illustrated and captioned each panel he did for the newspapers.

Last year I decided I would secure the 25 volumes in The Complete Peanuts and read about Charlie Brown from the beginning, since Charlie and I were born the same year. I’ve aged since then while Charlie never did, though he certainly matured over the years. I knew that Schulz wanted to call the comic strip Li’l Folks, but I didn’t realize until reading this collection that the name was changed by the syndicate as homage to the Peanut Gallery, where kids sat for The Howdy Dowdy Show, my favorite TV production as a child. Thus, Peanuts referred to the little folks, though Schulz never really liked the title.

I have just started volume 19, covering the years 1987-88, and have enjoyed this chance to meet all the characters from the beginning and to re-live the trends and issues I grew up with as reflected in the comic strip.

My favorite character, of course, is Snoopy, the Walter Mutty of the canine world and an aspiring writer. His travails at the typewriter and the hilarious rejection letters provide a genuine window into the life of a writer. Snoopy remains the greatest writer in comic strip history, adapting to the publishing trends of the time. For instance, when Lucy tells him that he needed to do a political thriller, he writes “It was a dark and stormy night,” then pauses before typing “Suddenly, a vote rang out!”

My favorite character, of course, is Snoopy, the Walter Mutty of the canine world and an aspiring writer. His travails at the typewriter and the hilarious rejection letters provide a genuine window into the life of a writer. Snoopy remains the greatest writer in comic strip history, adapting to the publishing trends of the time. For instance, when Lucy tells him that he needed to do a political thriller, he writes “It was a dark and stormy night,” then pauses before typing “Suddenly, a vote rang out!”

Other characters, such as Sally, also give great writing insight as well. For instance, in the Sept. 25, 1984, strip, Sally tells her big brother “Our homework assignment is to describe a sunset.” She thinks for a moment, then writes, “The Sun went down as red as a banana.” She turns to Charlie Brown and then says, “Makes you appreciate the beauty of the written word, doesn’t it?”

During its peak, Peanuts ran in 2,600 papers in 75 countries and in 21 languages. In all, Schulz illustrated almost  18,000 strips over his 50 years of doing Peanuts and took but one vacation, a five-week break to celebrate his 75th birthday. He not only wrote short, but he also wrote well on a daily basis with great insight into life. Fortunately, “Classic Peanuts” still runs in many newspapers and a variety of animated specials still keep the lovable loser Charlie Brown and all his friends in our hearts and minds.

18,000 strips over his 50 years of doing Peanuts and took but one vacation, a five-week break to celebrate his 75th birthday. He not only wrote short, but he also wrote well on a daily basis with great insight into life. Fortunately, “Classic Peanuts” still runs in many newspapers and a variety of animated specials still keep the lovable loser Charlie Brown and all his friends in our hearts and minds.

For those that want to re-live the Peanuts experience and to enjoy its humorous insights into writing, I recommend The Complete Peanuts.

January 8, 2018

Thumbs Up for Bluster’s

Last year ended with a flurry of great Web reviews for Bluster’s Last Stand. What is most gratifying is that whatever flaws the reviewers found, they all liked my protagonist, H.H. Lomax.

The Lone Star Literary Life website started its review this way: “Reading nineteenth-century Old West memoirs can be a fast way to fall asleep — unless they have been written in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by San Angelo novelist Preston Lewis, a Spur Award winner and former president of the Western Writers of America. Bluster’s Last Stand is the frequently hilarious fourth book in Lewis’s Memoirs of H. H. Lomax series. In this new entry, Lomax survives the Battle of Adobe Walls, gets into a deadly feud with General George Armstrong Custer (whom he derides as ‘General Bluster’), and later lands an unusual job in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Along the way, he also works as a bouncer and guard in a Waco bordello and prospects for gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota.”

The Lone Star Literary Life website started its review this way: “Reading nineteenth-century Old West memoirs can be a fast way to fall asleep — unless they have been written in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by San Angelo novelist Preston Lewis, a Spur Award winner and former president of the Western Writers of America. Bluster’s Last Stand is the frequently hilarious fourth book in Lewis’s Memoirs of H. H. Lomax series. In this new entry, Lomax survives the Battle of Adobe Walls, gets into a deadly feud with General George Armstrong Custer (whom he derides as ‘General Bluster’), and later lands an unusual job in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Along the way, he also works as a bouncer and guard in a Waco bordello and prospects for gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota.”

LSLL concludes “Bluster’s Last Stand is clever, absorbing Old West entertainment, a book that delights as well as informs.”

The Clueless Gent blog posed several questions: “Do you have to be an historical fiction aficionado to enjoy Bluster’s Last Stand? NOPE. Do you have to enjoy tall tales of the ‘Old West’ to find this story engaging? NOPE. Did I find this book particularly fun to read? Hell yeah!!!! Why? CHARACTERS!!!! … H.H. Lomax had an uncanny way of being in the wrong place at the wrong time (or the right place at the right time, depending on your perspective). … H.H. Lomax has quickly become one of my very favorite characters!”

The Reading by Moonlight blog by Ruthie Jones said “Bluster’s Last Stand is absolutely hilarious. Traipsing alongside H.H. Lomax, aka Leadeye Lomax, as he goes about his adventures is fun and exhilarating, to be sure. But it’s Lomax himself who provides the most entertainment, with his quick wit, ingenuity, and uncanny ability to always land on his feet. Lomax’s escapades in Bluster’s Last Stand take the reader on a wild ride from beginning to end. The writing is quite snappy, and Lomax’s attitude as he muddles through his predicaments is both pragmatic and amusing. Preston Lewis’s ability to develop a character is second to none.”

The Missusgonzo blog concluded “Even if you don’t care much for history, I think you will find this book entertaining. Lomax’s hilarity and heart of gold soften the blow of the harsh realities in this part of history, and make them interesting. Or if you want to set the humor aside, there are some provoking thoughts on morality and perception that might stir you up. I look forward to reading more about Lomax’s adventures.”

Very gratifying, these reviews. A couple reviewers, however, dinged the book for a “very few” comma and spelling errors, but in my defense I am, after all, transcribing from Lomax’s pencil-written recollections on Big Chief tablets.

December 21, 2017

Bluster’s Dozen

In researching Bluster’s Last Stand, I read close to a hundred books on Custer and the Little Bighorn in search of historical details and odd facts I could use in my novel. The nice thing about writing fiction is that you can use the accounts that serve your story best without having to confirm their authenticity. These are the volumes that were the most helpful in constructing my novel.

1) A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn – the Last Great Battle of the American West by James Donovan (Best modern synthesis of the battle with a fresh look at some previously discounted claims related to the battle.)

1) A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn – the Last Great Battle of the American West by James Donovan (Best modern synthesis of the battle with a fresh look at some previously discounted claims related to the battle.)

2) Deliverance from the Little Big Horn: Doctor Henry Porter and Custer’s  Seventh Cavalry by Joan Nabseth Stevenson (A solid account of the doctor who treated the wounded and escorted them back to Fort Abraham Lincoln on the Far West. Good detail on the aftermath of the battle.)

Seventh Cavalry by Joan Nabseth Stevenson (A solid account of the doctor who treated the wounded and escorted them back to Fort Abraham Lincoln on the Far West. Good detail on the aftermath of the battle.)

3) Custer Survivor: The End of a Myth, the Beginning of a Legend by John Koster (A credible account with supporting evidence of a possible survivor.)

4) Arikara Narrative of Custer’s Campaign and the Battle of the Little Bighorn by Orin G. Libby (The recollections of nine Arikara scouts who accompanied the campaign.)

5) Participants in the Battle of the Little Big Horn: A Biographical Dictionary of Sioux, Cheyenne and United States Military Personnel by Frederic C. Wagner III (This compilation of known details of various participants allowed me to choose actual soldiers to include as characters in the novel.)

5) Participants in the Battle of the Little Big Horn: A Biographical Dictionary of Sioux, Cheyenne and United States Military Personnel by Frederic C. Wagner III (This compilation of known details of various participants allowed me to choose actual soldiers to include as characters in the novel.)

6) I Go With Custer: The Life & Death of Reporter Mark Kellogg by Sandy  Barnard (This account examines the newspaper reporter who accompanied the fateful and fatal expedition.)

Barnard (This account examines the newspaper reporter who accompanied the fateful and fatal expedition.)

7) Custer’s Luck by Edgar I. Stewart (A solid examination of the Indian Wars and Custer’s role in them.)

8) The Battle of the Little Bighorn by Mari Sandoz (A classic account of the battle and one of the first to highlight Custer’s political ambitions as a possible influence on his decisions)

9) The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn by Nathaniel Philbrick (Another solid modern account of the battle and its participants)

10) Little Big Horn Diary: A Chronicle of the 1876 Indian War, Vol VI, Custer Trail Series, by James Willert (A day-by-day account of the Custer expedition, pulling together facts from multiple sources into a single work.)

10) Little Big Horn Diary: A Chronicle of the 1876 Indian War, Vol VI, Custer Trail Series, by James Willert (A day-by-day account of the Custer expedition, pulling together facts from multiple sources into a single work.)

11) Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America by T.J. Stiles (A Pulitzer Prize winner for history placing Custer and his travails in the context of the times and the nation.)

12) 1876 Facts About Custer And The Battle Of The Little Big Horn by Jerry Russell (A potpourri of interesting, unusual or lesser known facts about Custer and his fateful expedition.)

December 11, 2017

Lomax Is Back!

With the release of Bluster’s Last Stand by Wild Horse Press this fall, my loveable scoundrel H.H. Lomax has returned with another misadventure, this time culminating at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The story of Lomax goes back to the mid-1990s when the editor of Bantam approached me about working with Book Creations Inc. (BCI) to create a character who roamed the Old West, crossing paths with the era’s legendary figures and, basically, gumming up the works. I was to create the character, the backstory and the tales in a first-person narrative that offered a new slant, hopefully humorous, on the time-worn tales of the frontier. In other words, Lomax was to be the guy in the ointment of the Old West.

The story of Lomax goes back to the mid-1990s when the editor of Bantam approached me about working with Book Creations Inc. (BCI) to create a character who roamed the Old West, crossing paths with the era’s legendary figures and, basically, gumming up the works. I was to create the character, the backstory and the tales in a first-person narrative that offered a new slant, hopefully humorous, on the time-worn tales of the frontier. In other words, Lomax was to be the guy in the ointment of the Old West.

So, I hit upon the idea, far from original, of a set papers that had been found in an archive. Thus, The Memoirs of H.H. Lomax were born in my mind. I got permission from the director of the Southwest Collection at Texas Tech University to write a foreword saying the papers were housed there. His only provision was that he would start a file at the archive on me, documenting that H.H. Lomax was merely the product of my imagination, so that some future archivist wouldn’t be pulling her hair out trying to find the lost memoirs I had written about.

I laughed at the request, doubting there would ever be a single inquiry about Lomax, but I was proven wrong after the first three volumes came out as there was a period when the Southwest Collection was fielding two or three Lomax queries a month. Unfortunately, after the third volume in the series came out, Bantam dropped its western and frontier lines, ending the literary career of my protagonist.

However, once I retired from university work, I acquired the rights to Lomax and worked with Wild Horse Press to bring the first three volumes—The Demise of Billy the Kid, The Redemption of Jesse James and Mix-Up at the O.K. Corral—back into print.

As Lomax had taken on Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and Johnny Ringo, among others, in the first three volumes, it was time to take on another western icon. So, I settled on George Armstrong Custer with peripheral characters of Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill Hickok, who I will utilize further in the fifth Lomax book I am currently researching.

So far, reviews for Bluster’s Last Stand have been good. Lone Star Literary Life called Bluster’s “frequently hilarious” and “clever, absorbing Old West entertainment, a book that delights as well as informs.” One reader posted on my Facebook page that she had been waiting 20 years for another Lomax book, writing “Lomax gave me everything I wanted in a frontier vagabond—exaggerated humor, misadventures, and imagination. He was everything the typical western protagonist was not, and I loved every line.”

I’ll be writing more on Lomax and Bluster’s Last Stand in coming days.

December 3, 2017

A Camel Born at Sea

My latest young adult novel, Just Call Me Uncle Sam, has now been published by Wild Horse Press. This is my third juvenile novel, but the first where I had actual kids help me write it. The book is the third in my Animal Legends series which looks at our Texas heritage through the eyes of animals that helped make that history.

The books follow the concept of Robert Lawson’s Ben and Me, a classic tale of Benjamin Franklin as told by his faithful mouse assistant Amos. This book as well as the Disney animated short of the same name were childhood favorites of mine.

The books follow the concept of Robert Lawson’s Ben and Me, a classic tale of Benjamin Franklin as told by his faithful mouse assistant Amos. This book as well as the Disney animated short of the same name were childhood favorites of mine.

Just Call Me Uncle Sam is about an actual camel that was born at sea on the way to Texas as part of the U.S. Army’s experiment to see if camels could provide more efficient transport of men and supplies in the arid Southwest. Without a doubt, they could, but soldiers and civilians alike found the animals repulsive and resisted any widespread utilization of the dromedaries.

So, I imagined what it must have been like to be a camel born at sea, trying to adapt to Texas and the Army with his parents. That’s where I needed a little help from The Grands in the resolution of the story. So, while they were at Camp Mema/Gulag P-Pa three years ago, I asked them each to give me a line that they might say to a camel that was about to go swimming.

“Why do you have a mountain on your back?” Miss Hannah offered. “Camels always sink when they are too big,” Miss Cora suggested. “No, no, no!” an emphatic Miss Miriam offered, while Miss Carys echoed her by suggesting “Hey, hey, hey!” which I turned to “Hay, hay, hay!” for dramatic purposes. Mr. Jackson was a little too young to understand what I was after so I took his comment about Camp Mema—“It’s a fun place to play!”—and adapted it to the story.

Since Miss Hannah was going through her horse phase of development, I gave The Grands equine names, creating Hannah and Miriam Horse and Cora, Carys and Jackson Colt as their character names. So I’ll be able to give each of them for Christmas a book naming them and incorporating their lines in the text. These are the types of schemes authors pull to amuse themselves, their kin and their friends.

October 7, 2017

O.K. Corral

Thanks to Wild Horse Press of Fort Worth, the third of my novels in The Memoirs of H.H. Lomax series is now back in print and available from on-line retailers. This is how Mix-Up at the O.K. Corral begins:

New Trade Paperback Cover

Things might have turned out different in Tombstone if I hadn’t had a toothache and Doc Holliday hadn’t had bad breath. A lot of men died as a result, though not likely as many as needed killing. If it hadn’t been my tooth, though, it’d probably have been something much less important that started all the trouble because there were more mean folk in Arizona Territory at the time than you’d find any place else in the country short of a suffragists’ convention.

The law was crooked in Tombstone, and it didn’t matter what side of the law you were on. The politics were crooked in Tombstone, too, which made it no different from most every other place else in the country. You couldn’t even buy a town lot without some greasy son of a bitch trying to claim it for himself. Nothing was straight in Tombstone, not even the liquor. I knew that for certain because I owned a saloon there, and I’d cut my whiskey with just about anything I could, even water—which was expensive at three cents a gallon—when nothing else was available.

Running a saloon is as respectable an occupation as, say, running for political office, and you get to meet a higher class of people. That’s how I met Doc Holliday, who threatened to cut out my gizzard, and Johnny Ringo, who offered to blow a hole in me wide enough to drive an ore wagon through, and the Earp brothers, who were rightly named because I always felt like throwing up around them.

As you can see, I took an irreverent look at the events of Tombstone. Besides that, this was the first book in which I ever made a cat into a significant character. That led to a series of events and assignments that allowed me to claim to be the world’s leading authority on cats in the Old West. It’s funny how a chain of events can lead to such a claim, pretty much like how the sequence of incidents in Tombstone led my protagonist H.H. Lomax to fire the first shot in the altercation near the O.K. Corral. At least that’s what Lomax claims!

June 26, 2017

Picture Books

As a writer, I am always fascinated by the differences in techniques for various forms of entertainment media. Over my career I’ve written numerous articles, 30 published novels, two produced playscripts (performed far, far from even off Broadway), one screenplay (unproduced and unlikely to see the big screen) and even a published poem.

So, I’ve thought a lot about writing over the years but never about the techniques of doing a graphic novel, a book that uses illustrations to help convey the story. You might say it is a comic book for grownups. During a session at the Western Writers of America meeting in Kansas City last week, I had the pleasure of meeting David Morrell, who identifies himself as “the father of Rambo” and as a writer of graphic novels, including projects on Wolverine, Spider-Man and Captain America: The Chosen.

So, I’ve thought a lot about writing over the years but never about the techniques of doing a graphic novel, a book that uses illustrations to help convey the story. You might say it is a comic book for grownups. During a session at the Western Writers of America meeting in Kansas City last week, I had the pleasure of meeting David Morrell, who identifies himself as “the father of Rambo” and as a writer of graphic novels, including projects on Wolverine, Spider-Man and Captain America: The Chosen.

Morrell explained how to write and format a “script” for graphic novels. When you look at a graphic novel, you might think there’s little to write except for dialogue. But in reality, the writer must describe the visuals for each panel and then use appropriate dialogue, thoughts or sound effects for the illustrations.

Creatively, developing a graphic novel is more akin to writing a screenplay than a novel, as it requires visuals and stylized action in addition to dialogue. To use the movie analogy, the graphic novel author is the writer, director and producer, all rolled into one. In addition to the writer, graphic novels require an illustrator and a colorist to produce.

Morrell did a great job of explaining the nuances of graphic novels and the artistry behind them. He is best known as the author of First Blood, the novel on which the Rambo movie franchise was built and a novel he described as a Western in disguise. Morrell has also written several other novels set in the southwest and Last Reveille, a historical novel on “Black Jack” Pershing’s pursuit of Pancho Villa into Mexico after the Columbus, New Mexico, raid in 1916.

Morrell did a great job of explaining the nuances of graphic novels and the artistry behind them. He is best known as the author of First Blood, the novel on which the Rambo movie franchise was built and a novel he described as a Western in disguise. Morrell has also written several other novels set in the southwest and Last Reveille, a historical novel on “Black Jack” Pershing’s pursuit of Pancho Villa into Mexico after the Columbus, New Mexico, raid in 1916.

One of the great things about WWA is the interesting people you meet, such as Morrell, and the opportunity to learn from them about creative writing in its many forms.

April 8, 2017

Gentleman of Letters

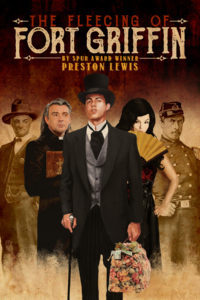

Fleecing Cover

I am proud to report that my western caper The Fleecing of Fort Griffin has received the Elmer Kelton Award for best creative work on West Texas from the West Texas Historical Association.

It is always an honor to see your work rewarded but this recognition is especially meaningful. First, it comes from an organization of people dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of West Texas, the land of my birth. The people and the land of West Texas shaped my life and my interests.

Second, it is named for Elmer Kelton, who was a mentor and friend to so many writers over the years. When I lived in Lubbock, I could claim—rightfully or wrongfully—to be the best western writer in town.

Elmer Kelton

Then I moved to San Angelo. I could no longer make that claim. Elmer called San Angelo home for most of his lifetime, and he was voted by Western Writers of America as the greatest western writer of all time.

Elmer was a wonderful writer but an even better person, a true gentleman of life and of letters. I look forward to hanging on my wall an award with his name upon it. Thanks to WTHA for bestowing this honor on me.

March 27, 2017

Old-Timer

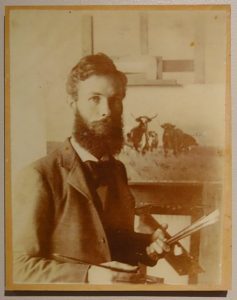

Frank Reaugh

You know you are getting old when you read a history book and realize you knew nine of the people mentioned. Encountering those names was an unexpected pleasure when I got a review copy of Rounded Up in Glory: Frank Reaugh, Texas Renaissance Man by Michael R. Grauer.

Reaugh (1860-1945), pronounced “ray,” was a Texas artist best remembered for his impressionistic pastels of Texas longhorns. Known as the “Leonardo of the Longhorn,” Reaugh was a peer of cowboy artists Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, but unlike them he was in Texas during trail-driving days and actually witnessed what he painted. He focused much more on the longhorn than the cowboy and produced hauntingly beautiful landscapes of West Texas.

An Illinois native, he came to Texas in 1876 and came to love the land, the longhorns and art, eventually earning the honorific title of “Dean of Texas Painters” for his plein air techniques and his influence on other outdoor Texas artists. His work “The Approaching Herd” is his best known piece.

The Approaching Herd by Frank Reaugh (Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum)

Reaugh is less remembered than Remington or Russell, who were much more commercial in outlook, selling their art, whereas Reaugh saw his body of work as a historical record of a time before the plains were fenced and plowed. When he died, his will stated that that he wanted his pictures to be kept together for historical reasons.

Problem was many had been split up among various institutions, including the Panhandle-Plains Museum in Canyon, the University of Texas and Texas Tech University and its Southwest Collection, where I did a lot of my early research and even served a year as interim director before I moved to Angelo State. The estate took more than two decades to settle, though some claims on ownership remain unresolved.

My Texas Tech connections mentioned in the book included former Southwest Collection Directors S. V. “Ike” Connor and R. Sylvan Dunn as well as administrators Curry Holden and Bill Parsley. The two mentioned TTU connections I got to best know were former Tech President Grover Murray and former Gov. Preston Smith, a Tech alumnus. My Western Writers of America affiliation allowed me to meet artist Tom Lea and Texas historians J. Evetts Haley and Don Worcester, who are also included in Rounded Up in Glory.

So, renewing old acquaintances in print has been an unanticipated joy in reading Rounded Up in Glory for review.

March 15, 2017

Ideas Aplenty

Probably the most frequent question I have gotten as a published author is this: Where do you get your ideas? My wife once asked me where I came up with all that stuff, though “stuff” was not her exact phraseology.

Even my daughter gave me a Father’s Day Card one year that read, “Fatherhood: the great art of making up crap on the spot.” She added, “I don’t know that I could ever find a more perfect card.”

Grandfather and Grandsons

Most writers have an active imagination and no dearth of ideas. The bigger problem for writers is culling their ideas to a manageable number. I have more book and story ideas than I have time and energy to write. The challenge is not to let new ideas overwhelm the old ones you’ve been developing.

The more intriguing question of writers, in my view, is why they chose a particular genre or writing specialty. In my case, it was family and environment that pushed me to western fiction. First, I loved to hear the stories of my Lewis aunts and uncles who grew up in the Great Depression as children of a tenant farmer. Their childhoods seemed more akin to life on the frontier than anything I was familiar with. Second, I grew up in West Texas where I was never far removed from cattle and the cowboy culture.

Pop culture also influenced me. The most popular television shows of my childhood were westerns, which drove me to the library to read more on the history and lore of the Old West. For five years, we lived on a place east of Midland that had corrals and barns and a section of pasture I could explore. The Covington place was even more exciting when Dad bought my brother and me a donkey. We could put a bridle on “Flash,” as we called him, and ride the Covington range on our western adventures.

Flash and Author

One of my favorite photos growing up was a profile of me with Flash. We don’t have many of the photos of the Covington place that show the outbuilding and corrals, but I do have one of my little brother and me with our Lewis grandfather where you can see some structures in the background. The place was cowboy heaven for me as it was all the fun my imagination could create without all the chores of ranch work.

The pivotal moment that branded a western fascination in my mind forever was when my parents during a vacation to Ruidoso made a side trip to Lincoln, where Billy the Kid roamed, fought and made his daring final escape. That excursion bridged the gap between my imagination and the West’s actual history, which is richer than the fictional West. I chose to write western fiction, however, because I didn’t have the patience and time to write history. Fiction satisfied my desire to write and to read history for background. Like Flash, it’s been a fun ride.