Preston Lewis's Blog, page 8

July 23, 2015

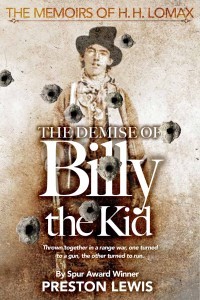

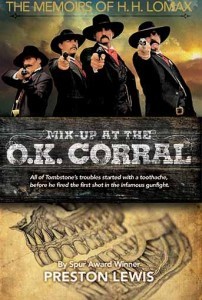

Latest Book Cover

It’s always fun to get a new book cover, even if it is for a reprint. This is the planned cover for Mix-Up at the O.K. Corral, the third volume in The Memoirs of H.H. Lomax. It’s not the typical western cover, though it has grown on me.  Compare it to the cover of The Demise of Billy the Kid, the first volume in the series, which has a more traditional look and feel.

Compare it to the cover of The Demise of Billy the Kid, the first volume in the series, which has a more traditional look and feel.

The cover of The Redemption of Jesse James, the second volume in the series, will be posted next week as it has a very unusual look to it, very atypical for a western.

July 14, 2015

Connections to the Past

One of the things I love about history is the connections you can make to the past.

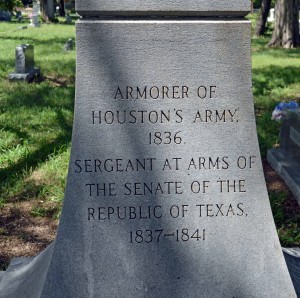

Grave of Noah T. Byars

This past week, Harriet and I made a connection all the way back to the Declaration of Texas Independence through Noah T. Byars, who is buried in Brownwood’s Greenleaf Cemetery.

A South Carolina native and subsequent Georgia resident, Byars came to Texas in 1835 and settled in Washington-on-the-Brazos, where he operated a gunsmith and blacksmith shop and became one of eight charter members of the very first Baptist church in what would later become Texas.

In 1836 when the residents of Texas declared their independence, the committee that drafted the document did so in his blacksmith shop and met with other delegates in a building he owned to adopt the declaration. Sam Houston subsequently appointed him armorer and blacksmith of the Texas army.

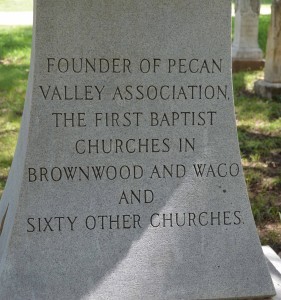

Byars’ Texas Accomplishments

After Texas became an independent nation, Byars felt the call to the ministry and was ordained as a Baptist minister on October 16, 1841. The ordination was attended by Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar as well as members of his cabinet.

Two years later Byars was named the Texas Baptist Convention’s first missionary, ministering to the sparsely settled region between the Trinity and Brazos rivers. Over the course of his ministerial career, he founded more than 60 Texas churches, including the First Baptist Church of Waco in 1851 and in 1876 the First Baptist Church of Brownwood, where he lived out his life and died in 1888.

Byars’ Baptist Accomplishments

So, what’s the connection? When Harriet and I married in 1971, we did so in Waco’s First Baptist Church, one of the earliest of the five dozen Baptist Churches he established during his career. We all have such ties to our past, if we just look for them.

July 4, 2015

Spur Begats Spur

It’s always good to see hard work pay off as it did last week for Patrick Dearen, a Sterling City native and longtime writer friend who now lives in Midland. Patrick earned a Spur Award from Western Writers of America for Best Western Traditional Novel for his book, The Big Drift, which is set in West Texas during the great blizzard, cattle drift and roundup of 1884-85.

Spur Winner Patrick Dearen

What I enjoy about writing and history are the connections you can make, and Patrick certainly made some connections during his acceptance speech when he acknowledged the influence on his career of Leigh Brackett’s historical novel Follow the Free Wind about legendary mountain man and one-time slave Jim Beckwourth.

“In 1963 Leigh Brackett won the Spur Award for best western novel,” Patrick said in his acceptance speech. “When I was 16 and discovered her amazing works and learned that she had won a Spur, I thought, ‘Wow, wouldn’t it be something to someday win the same award that she did?’ Well, it’s taken 48 years, but thanks to WWA, Melinda Esco and TCU Press, and God’s grace, I’m living that dream tonight.”

Patrick’s acceptance was touching and gracious, highlighting the influence of a talented writer whose name is largely unrecognized, but whose works in science fiction and especially on the movie screen are known to millions. Brackett you see was the original screenwriter on The Empire Strikes Back, the second installment of the original Star Wars trilogy.

Her other screenwriting credits include The Big Sleep (with William Faulkner), 1946; Rio Bravo, 1959; Hatari!, 1962; El Dorado, 1967; Rio Lobo, 1970; The Long Goodbye, 1973; and The Empire Strikes Back (with Lawrence Kasdan), 1980.

The Empire Strikes Back is generally considered the best of the Star Wars movies, though Brackett’s contribution may have been lessened by her untimely death. Shortly after she delivered the Empire screenplay, she died. Lawrence Kasdan and George Lucas worked on the screenplay after her death, though only Kasdan received a writing credit with Brackett. Some even suggest that the character Yoda was her creation.

So, the point is this: the reach of writers often extends long beyond their time on earth. Who knows? Perhaps Patrick Dearen’s work will inspire another Spur winner a half century from now.

June 30, 2015

Western Writers Hall of Fame

During the Western Writers of America convention, I had the opportunity to attend this year’s induction into the Western Writers Hall of Fame. After the 2015 ceremony, the Hall of Fame, which is housed at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, has 91 members.

Setting for Western Writers Hall of Fame Induction

Due to my association with WWA for the past third of a century, I can claim to have met or known 38 of the inductees. Two of those inductees – the late Elmer Kelton and Jeanne Williams of Portal, Arizona –were important in my writing career.

West Texas native Kelton, who is considered the greatest western writer of all time, was especially supportive of my early writing efforts and encouraged me to join WWA to begin with. His advice to me and every other writer he ever consulted was “don’t quit your day job.” It was advice he followed, working for years as editor of Livestock Weekly and writing westerns in the evenings and on weekends.

I would consider Williams as my writing mentor. She read a carbon mind you of my first historical novel, which was subsequently published as The Lady and Doc Holliday, and encouraged me to continue my writing. She said she had met a lot of writers over the years and had decided it wasn’t talent as much as persistence that led to getting published. After reading the faint carbon, she said she thought I had the talent and it was just a question of whether or not I had the persistence. She even told the kids she thought I would win multiple Spur Awards before I was done. She hosted my family on two occasions at her home in Cave Creek Canyon, where she had the most beautiful writing room I have ever seen. Her writing desk faced a picture window where she could look down the canyon and enjoy the humming birds and the changing seasons.

Both Kelton and Williams even provided cover blurbs for me when The Lady was published.

Max Evans with me

The oldest inductee to attend the induction ceremony was Max Evans, 91, of Albuquerque, N.M. He began his career as a cowboy and turned to writing at age 35. His book, The Rounders, was made into a 1960 film starring Glenn Ford and Henry Fonda. One of the great thrills of my writing career was getting a call one day at work from Evans, saying he was in Lubbock and he would like to meet me, if I had the time. I certainly did! Since then, I have gotten to know him and his wife, Pat, who is as good a story teller as Ol’ Max, as he is affectionately known.

One of the benefits of being a writer is that you get to meet other authors, whose support and encouragement help you through the tough times.

June 19, 2015

Fort Griffin Fandangle

Of all the Old West towns I’ve read about over the years, Fort Griffin, remains my favorite, but not until this year had I ever had the opportunity to attend the Fort Griffin Fandangle, produced by the citizens of nearby Albany, Texas.

Fandangle Flag Parade

We attended the opening performance of the 77th edition of the Fandangle on Thursday night and found it to be the most entertaining outdoor production we had ever attended. It was an amusing mix of music, drama, humor and history, tracing the growth and demise of the frontier community. Fort Griffin the town took its name from the military post of the same name established in 1867 on a plateau overlooking the Clear Fork of the Brazos in what is today northern Shackelford County.

The town grew as a festering scab at the foot of “Government Hill,” as the military post was called by the locals. The town took on a variety of sobriquets, ranging from “The Flat” to “Sodom of the Prairie.” Fort Griffin was where Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp first met and where the legendary lady gambler Lottie Deno plied her skills before disappearing from history. The town was the setting for my first historical novel, The Lady and Doc Holliday. What I liked about the historic town of Fort Griffin was its convergence of Comanche, military, ranching, trail driving and outlaw history.

Fandangle Thundering Herd

What I liked about the Fandangle was the homage to the region’s history, told with humor, clever lyrics and the spectacle of galloping horses, rumbling wagons and stage coaches, and more than 300 Albany citizens in colorful costumes celebrating their heritage.

Until Thursday night, I’d never had a herd of longhorns charge right at me or seen a rattlesnake drink whiskey, even if it was a mechanical serpent. The rattlesnake, which appears during a drunken cowboy’s reverie, is the most requested feature of the show, which varies from year to year.

The Fandangle Kid

This year the theme focused on frontier children and one of the joys of the performance was watching the kids from toddlers to teens singing, dancing, fighting their costumes or just looking cute at the feet of their parents. Some of the children in the play were fifth generation performers in the Fandangle, first presented in 1938.

After the military post was abandoned in 1881 and the Texas Central Railroad bypassed The Flat for Albany in December of the same year, Fort Griffin the town slowly atrophied away. Today the abandoned Masonic Lodge is the only original building still standing in the once thriving town. Up on Government Hill, the ruins of the fort remain under the care of the Texas Historical Commission, which has just opened a visitor center.

Albany, Fort Griffin and the Fandangle are all worth a visit if you ever get a chance as we certainly had an entertaining afternoon and evening immersed in the region’s history.

May 28, 2015

Texas Falling

I missed the first installment of Texas Rising as I was out of town, but picked up the second part of the History Channel’s mini-series. I must admit I was disappointed.

While I favor historical movies and westerns, this one left me perplexed because of its historical inaccuracies, which far exceed acceptable dramatic license in my view, and most especially because of its inaccurate settings. I have been to most of the sites associated with Texas war for independence and they are nothing like the desert landscapes used in Texas Rising.

While other landscapes have often substituted for Texas in Hollywood’s vision of the Lone Star State, most notably with Monument Valley in John Ford’s classic The Searchers, generally the plot or the characters helped overcome the geographic inaccuracies. Nothing I saw in the second installment allowed me to suspend disbelief long enough to enjoy the so called re-telling of the Texas story, especially in an alien landscape.

In reviewing the mini-series for Texas Monthly, Stephen Harrigan said there’s so little genuine Texas history in the production that the History Channel, which seven years ago re-branded itself simply “History,” should consider another name change to just “Channel.” Well said!

Texas Rising may be enthralling for those with little knowledge of Texas history, but it is most annoying for those of us with a little knowledge of the state’s heritage.

May 9, 2015

Writing Mentor: David McHam

One of my luckiest breaks in life was attending Baylor University when I did because I was able to get a journalism education under David McHam, who provided the foundation for my writing career and got me my first professional job in journalism.

McHam, as everyone called him at Baylor, announced this month that he is retiring from the University of Houston at the end of the spring semester. His retirement comes after 54 years of teaching Texas college journalism at Baylor, SMU, UT-Arlington and UofH. Though well deserved, his retirement is a loss to the profession.

David McHam during Baylor years

McHam taught at Baylor from 1961-74, leaving for SMU two years after I graduated. I began in journalism thinking I would go into sportswriting. When McHam found that out and got a call one Friday afternoon from the Waco News-Tribune asking if he knew anyone who could cover a game on short notice, he called this freshman and offered me the opportunity. I was excited but had two problems: 1) I’d never covered a game before; and 2) I didn’t have transportation to get to the game. He gave me a five-minute lesson on keeping a running play-by-play and compiling a stat sheet, then loaned me his pickup.

Off I went and the next morning I had my first byline in a daily newspaper. As a result of his faith in me, I worked Friday night football at the Waco paper all four years in college. When I was a senior, I was hired full-time by the News-Tribune in sports and had the opportunity to work under legendary sports writer/editor Dave Campbell.

I had always desired to write, but by the time I was a Baylor sophomore I was questioning why I had to take the required editing courses. I know, it sounds dumb in retrospect, but I was young and wanted to be a writer, not an editor. So, I went to McHam and asked if I really had to take the editing courses. He nodded and smiled. “Preston,” he said, “I think you will find that good writing is good editing.”

That’s the only verbatim quote I remember from any of my teachers over the years, probably because it was such a good mantra for writing of any kind. Today when I write, whether a book-length piece or a blog, I always go through three drafts. The first is just to get the words down. The second two drafts are to edit and polish the language. The first draft is tedium. The editing drafts are fun.

It’s not just me that thinks highly of McHam, either. He is respected by his peers, both in academic and professional journalism nationally. He was named the country’s outstanding journalism teacher by the Society of Professional Journalists in 1994 and earned a president’s award from the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communications in 2001.

So, thank you, David McHam, for your influence on me and so many other aspiring writers and journalists.

April 26, 2015

Texas Bluebonnets

Landscape is an essential part of most westerns and this weekend we traveled to the Texas Hill Country around Mason in search of Lupinus texensis, better known as the Texas Bluebonnet. Yes, who can live in Texas without going on a wildflower safari each spring?

Mason County Bluebonnets

Based on our drives through the Hill Country over the last 15 years since we moved to San Angelo, this year’s crop was only exceeded by that of 2004. We were likely a week to 10 days past this year’s prime growth, but it was still a beautiful splash of color across the meadows and hills made green by spring rains.

The Bluebonnet has been the state flower of Texas since 1901 when the 27th Texas Legislature designated the native plant as such. The Lupinus texensis is one of the state’s five native bluebonnet species, all of which were officially made state flowers by the Texas Legislature in 1971.

Legend says the Spanish priests who came to Texas loved the flower and planted it around their missions, naming it el conejo or the rabbit. It took its common English name from the resemblance of its petals to the bonnets of pioneer women, who loved the flower’s subtle spring colors in a land that was often harsh and unforgiving.

Until the 1930s, the Bluebonnet’s range was limited to certain areas of the state, but during the Great Depression the Texas Highway Department began to beautify the state’s highways by planting seeds on the right of way. In the 1960s Lady Bird Johnson’s highway beautification program furthered the reach of the legume, a family of plants that includes mesquite, peas, beans, alfalfa and peanuts, among others.

Mason County Wildflowers

Today the bluebonnets are found throughout most of Texas along major and minor highways where their soft and dark blues provide a delicate canvas that makes the vibrant colors of the Indian Paintbrush, Indian Blanket, Buttercups and others that share the roadside. To see how they appeared to the early Texas settlers, you have to leave the main thoroughfares for rural and even private roads.

To help visitors find wildflowers in their natural setting, the Mason Chamber of Commerce provides directions to three routes that help you discover Texas wildflowers in their natural environments. We took routes two and three. The results were worth it, providing a step back in time to the days when the land was as wild as the flowers. Though the land has been tamed by modernity, the flowers remain as wild as ever and their beauty only truly appreciated when you pass them at 20 rather than 70 miles an hour and take the time to walk among them with your camera.

April 13, 2015

Quanah’s Birthplace

I just returned this weekend from the annual meeting of the West Texas Historical Association, which always offers an interesting program of presentations on the region’s history. One of the most fascinating papers was by Holle Humphries on “Quanah Parker was Born Simultaneously in Both Texas and Oklahoma.”

Comanche Chief Quanah Parker

Her presentation explored the legends behind Quanah Parker’s birthplace, which has been narrowed down to three possible locations in Texas and one in Oklahoma. Each location can make a legitimate, though not definitive, claim to being the future Comanche chief’s birthplace. The uncertainty is to be expected among a nomadic people as the Comanches were until they were forced onto the reservation.

Considered the last chief of the Comanches, Quanah Parker was a transitional figure who straddled both cultures as the son of a white captive, Cynthia Ann Parker, and a Comanche chief, Peta Nocona. After surrendering his band of Quahadi Comanche to federal authorities in 1875, Quanah helped his tribe make the transition to a new life.

Even to the end of his life, he gave contradictory signals to the question of his birthplace. After Holle’s presentation, which was moderated by Bruce E. Parker, a direct descendant of Quanah, a member of the audience asked the Parker family’s position on the great chief’s actual birthplace. Moderator Parker replied that it was not as important where he was born as much as that he was born.

The modern Parker’s response was a great answer and a reminder that some questions do not have historically definitive answers and likely never will.

April 7, 2015

Aliases

Occasionally, I get asked why I’ve written under various pennames. The answer can be simple or complex, but either way it carries on a great literary tradition. Mark Twain, of course, was actually Samuel L. Clemens, Lewis Carroll was really Charles Dodgson and George Orwell was Eric Arthur Blair in reality.

Likewise, numerous women have written under pseudonyms over the years, especially when the times were unsympathetic to female authors or the women wrote in fields traditionally considered the domain of men. So, Mary Ann Evans wrote under the pen name George Eliot and other women used their initials to disguise their gender as recently and successfully as J.K. Rowling, creator of Harry Potter.

First Hardy Boys Book

If you ever read the Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew growing up, you have been entertained by multiple authors writing under a nom de plume. Franklin W. Dixon wrote the Hardy Boys mysteries starting in 1927 and Carolyn Keene penned the Nancy Drew series beginning in 1930 for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, but both Dixon and Keene were “house names” for multiple authors. The use of house names is common for firms publishing book series.

First Nancy Drew Book

I’ve worked on a couple series for various publishers and have had books published under the names Stephen Calder on the Bonanza series for Bantam and Dale Colter in The Regulator series for HarperPaperbacks. For the Bonanza series, based on the original TV show, Stephen Calder was a name Frank Roderus and I came up with in a San Angelo diner during a Western Writers of America meeting. Each of us wrote three books in the six-book series. The name Dale Colter came from Harper when I signed to do a book in that series. Both were house names, contractually belonging to the publishers.

First Will Camp Book

The personal pseudonym I owned and wrote under was Will Camp, which was the name of one of my great-great grandfathers, who was a colorful character. You will notice that each of the pseudonyms starts with the letter “C,” which was intentional. Generally, mass market paperbacks are displayed alphabetically by author on book racks. Using a pseudonym starting with an “A,” “B” or “C” generally guarantees that your books will be at eye-level on the book rack. Few pseudonyms begin with “Z,” which would put your book at ankle-level.

So for me, the use of pseudonyms was a function of two factors. First, publishers do not like competing books by the same author coming out from a rival publisher. By using a pseudonym I could work with multiple publishers and get more books released in a single year. Second, I used my name and pseudonym to differentiate the type of book I wrote. For historical novels, I used my regular name. For more traditional westerns, I used Will Camp.

Because the book industry has changed significantly over the last decade with the influx of economical self-publishing and e-books, pseudonyms are not as important or useful as they once were, unless you want to hide your true identify.