Jim Shooter's Blog, page 13

August 17, 2011

Writer Editors – Part 5

"I'll Never Doubt You Again."

One afternoon toward the end of April, 1980, I got a call from Marvel President Jim Galton. He said that Roy Thomas had asked for a meeting with him to discuss renewing his contract with Marvel.

Roy had written a letter dated April 10 (I have the original) to Galton informing him that he had not been able to work out a new contract with me and that he was leaving Marvel. That prompted the call I got from Galton immediately thereafter. He said, among other things, that he thought I'd told him Roy and I had worked out a deal. What happened? What went wrong? How could I lose Roy?

Do you know how important to Marvel Roy must have been for Galton to even know who he was? Galton, the same man who once asked me who Gene Colan was. Galton, who didn't know who John Byrne was. Or John Buscema. Or anyone else, except Chris Claremont, who had an uncanny (←heh) knack for running into Galton on the elevator and introduced himself.

But Galton knew Roy, the man who had gotten us the Star Wars license among many other things.

In fact, Roy and I had worked out a new contract. On April 1, he sent me a letter that starts:

"Dear Jim,

I'm returning the copies of the contracts you sent me. I will sign them if each of the following changes is made:"

The changes were few and entirely reasonable. No problem. We made them immediately.

I also reassured him regarding his concern that the staff editor who would henceforth be responsible for overseeing the editorial work on his books would not be summarily "overruling" him, that if any disagreements came up, no action would be taken without his consent. If no agreement could be reached, he had outs.

I thought the contract would work well. It brought the logistics in house. No more "branch office" coordination problems, exacerbated by the fact that Roy lived on the West Coast. Central fire control.

Roy would still have in his hands every meaningful, creative part of editing. And was going to be paid better. But I was going to have someone responsible on hand to head off calamities, prevent problems and eliminate the falling-between-the-coasts glitches. By "calamities" I'm speaking mostly of schedule calamities.

It was fine by me for Roy to keep his editor credit. It wasn't about "demoting" Roy, it was about engineering a system that would work—that would give Marvel full advantage of his super powers with fewer problems.

But Roy had reneged. He changed his mind.

I explained all that to Galton. I suspect he thought, as many people still think to this day, that it was my fault. That I bungled it, or let it drift away from business into ego-rassling or personalities.

One thing about Galton, he was proper about business things. Roy went over my head, and normally, Galton wouldn't tolerate that. He would have refused the meeting. But, A) Roy was that important, B) he had already quit, so one could argue that this was a new negotiation, and C) Galton's way of observing proper protocol was by inviting me to the meeting.

So, the next morning, Galton and I were sitting in his office upstairs waiting for Roy to arrive. Galton asked and I explained my position and some of the contentions we'd encountered. Galton had become more adamant than I was about the no-writer-editor thing by this point. As I said, he'd never liked the idea and had hardened against it. However, since Roy had asked for the meeting Galton was confident that a deal could be made. I took that as an instruction to be as reasonable, businesslike, dispassionate and ego-free as possible and make a deal!

Roy arrived. As he entered Galton's office, he seemed taken aback that I was there. I guess he expected that going over my head was going to keep me out of it, but like I said, that wasn't Galton's style.

Roy expressed his interest in continuing to work with Marvel. Galton said he was pleased and hoped we could make that happen. And, again, in keeping with protocol, Galton turned the conversation over to me. I, too, said that we sincerely wanted Roy to stay with Marvel and wanted to work things out. I laid out the terms we proposed. Nothing different than what had been offered before, really, but I tried to reassure Roy that he and I could work together.

Roy agreed to everything. He even seemed comfortable and content with having a staff editor overseeing things.

Galton looked at me as if I must be crazy. It was a look that said, "This is the most reasonable man on Earth. Why couldn't you work out a deal?"

Galton said it seemed that Roy and I agreed on everything. Why didn't the two of us go downstairs and sign the contract?

Roy said that there was just one thing…he'd already signed an exclusive contract with DC Comics, but it had an exception that allowed him to keep writing Conan, so what he wanted now was a contract with Marvel to do the Conan books.

Galton looked at Roy as if he must be crazy. It was a look that said, "Suddenly I understand the problem."

Being 'exclusive' at DC but working part-time for us…. What message does that send? We're the losers in the Roy Thomas sweepstakes but he's so wonderful and we're so desperate that we need to cling to any shred of him we can get?

Annoyed big time, Galton told him that we weren't interested, that Roy had wasted our time and basically, to get out of his office.

Once Roy had been chased away, Galton told me, and this is a quote, "I'll never doubt you again."

P.S. And he didn't, in any significant way. During the JLA/Avengers mess, for instance.

Then why did I walk out of that room feeling like I'd lost?

NEXT: Years Later

One afternoon toward the end of April, 1980, I got a call from Marvel President Jim Galton. He said that Roy Thomas had asked for a meeting with him to discuss renewing his contract with Marvel.

Roy had written a letter dated April 10 (I have the original) to Galton informing him that he had not been able to work out a new contract with me and that he was leaving Marvel. That prompted the call I got from Galton immediately thereafter. He said, among other things, that he thought I'd told him Roy and I had worked out a deal. What happened? What went wrong? How could I lose Roy?

Do you know how important to Marvel Roy must have been for Galton to even know who he was? Galton, the same man who once asked me who Gene Colan was. Galton, who didn't know who John Byrne was. Or John Buscema. Or anyone else, except Chris Claremont, who had an uncanny (←heh) knack for running into Galton on the elevator and introduced himself.

But Galton knew Roy, the man who had gotten us the Star Wars license among many other things.

In fact, Roy and I had worked out a new contract. On April 1, he sent me a letter that starts:

"Dear Jim,

I'm returning the copies of the contracts you sent me. I will sign them if each of the following changes is made:"

The changes were few and entirely reasonable. No problem. We made them immediately.

I also reassured him regarding his concern that the staff editor who would henceforth be responsible for overseeing the editorial work on his books would not be summarily "overruling" him, that if any disagreements came up, no action would be taken without his consent. If no agreement could be reached, he had outs.

I thought the contract would work well. It brought the logistics in house. No more "branch office" coordination problems, exacerbated by the fact that Roy lived on the West Coast. Central fire control.

Roy would still have in his hands every meaningful, creative part of editing. And was going to be paid better. But I was going to have someone responsible on hand to head off calamities, prevent problems and eliminate the falling-between-the-coasts glitches. By "calamities" I'm speaking mostly of schedule calamities.

It was fine by me for Roy to keep his editor credit. It wasn't about "demoting" Roy, it was about engineering a system that would work—that would give Marvel full advantage of his super powers with fewer problems.

But Roy had reneged. He changed his mind.

I explained all that to Galton. I suspect he thought, as many people still think to this day, that it was my fault. That I bungled it, or let it drift away from business into ego-rassling or personalities.

One thing about Galton, he was proper about business things. Roy went over my head, and normally, Galton wouldn't tolerate that. He would have refused the meeting. But, A) Roy was that important, B) he had already quit, so one could argue that this was a new negotiation, and C) Galton's way of observing proper protocol was by inviting me to the meeting.

So, the next morning, Galton and I were sitting in his office upstairs waiting for Roy to arrive. Galton asked and I explained my position and some of the contentions we'd encountered. Galton had become more adamant than I was about the no-writer-editor thing by this point. As I said, he'd never liked the idea and had hardened against it. However, since Roy had asked for the meeting Galton was confident that a deal could be made. I took that as an instruction to be as reasonable, businesslike, dispassionate and ego-free as possible and make a deal!

Roy arrived. As he entered Galton's office, he seemed taken aback that I was there. I guess he expected that going over my head was going to keep me out of it, but like I said, that wasn't Galton's style.

Roy expressed his interest in continuing to work with Marvel. Galton said he was pleased and hoped we could make that happen. And, again, in keeping with protocol, Galton turned the conversation over to me. I, too, said that we sincerely wanted Roy to stay with Marvel and wanted to work things out. I laid out the terms we proposed. Nothing different than what had been offered before, really, but I tried to reassure Roy that he and I could work together.

Roy agreed to everything. He even seemed comfortable and content with having a staff editor overseeing things.

Galton looked at me as if I must be crazy. It was a look that said, "This is the most reasonable man on Earth. Why couldn't you work out a deal?"

Galton said it seemed that Roy and I agreed on everything. Why didn't the two of us go downstairs and sign the contract?

Roy said that there was just one thing…he'd already signed an exclusive contract with DC Comics, but it had an exception that allowed him to keep writing Conan, so what he wanted now was a contract with Marvel to do the Conan books.

Galton looked at Roy as if he must be crazy. It was a look that said, "Suddenly I understand the problem."

Being 'exclusive' at DC but working part-time for us…. What message does that send? We're the losers in the Roy Thomas sweepstakes but he's so wonderful and we're so desperate that we need to cling to any shred of him we can get?

Annoyed big time, Galton told him that we weren't interested, that Roy had wasted our time and basically, to get out of his office.

Once Roy had been chased away, Galton told me, and this is a quote, "I'll never doubt you again."

P.S. And he didn't, in any significant way. During the JLA/Avengers mess, for instance.

Then why did I walk out of that room feeling like I'd lost?

NEXT: Years Later

Published on August 17, 2011 08:58

August 16, 2011

Writer/Editors – Part 4

Roy

The tale of the contract negotiations with Roy is too long to tell in blow-by-blow detail. I'll tell you a bit of what I understand to be his side and a little of mine.

I think we both sincerely believed in the validity of our positions. I think each of us handled things badly at some points. I don't think there ever was any malice on Roy's side and there was none on mine, though Roy apparently felt otherwise sometimes.

Yesterday, I showed you a stack of contracts and drafts of same and a file full of letters from Roy. The contracts are what they are, no shocking revelations there.

The letters break down into four categories, basically:

Business stuff – regarding vouchers, contracts, schedules, policy matters and the like; also his side of any debates or controversies.

Ideas for new books, including some suggestions for other people, like Jack Kirby. Lots of ideas.

His plans for upcoming issues of each series he was working on. He was the only writer/editor to offer that courtesy. The only writer, for that matter.

Complaints about mistakes.

There were lots of the latter.

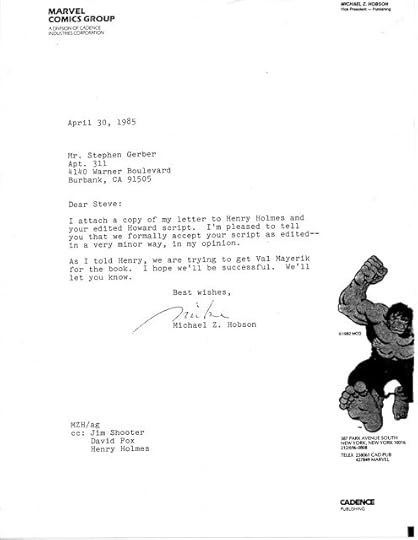

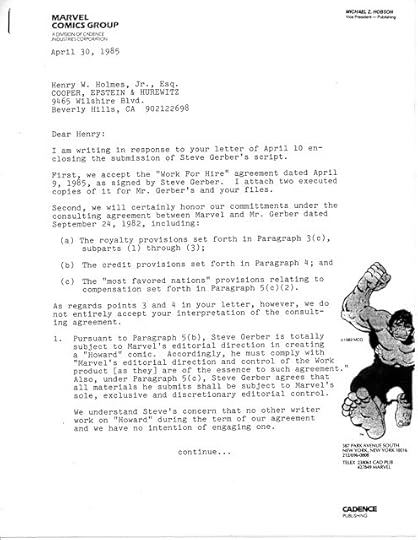

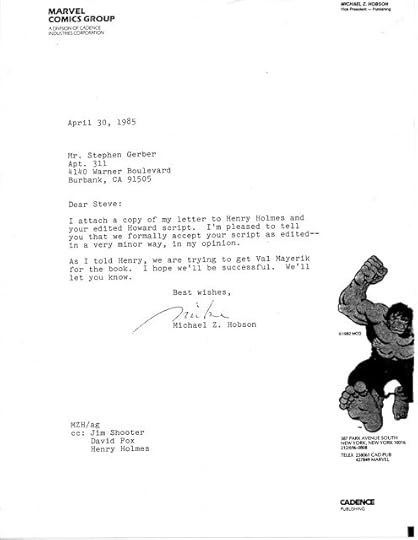

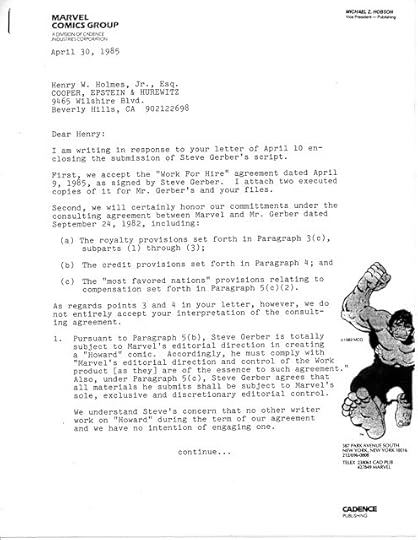

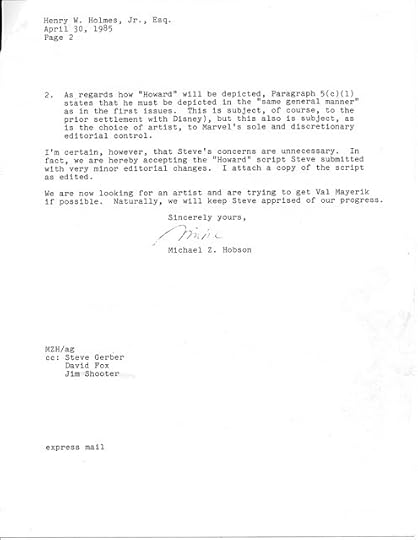

Roy's letters aren't simply business documents (as were Mike Hobson's letters regarding the Gerber script posted here a while ago). They're business related, but written person to person—one coworker to another, with informality appropriate to addressing someone you know. They weren't written for public display, and I will respect that. I will quote a passage here and there.

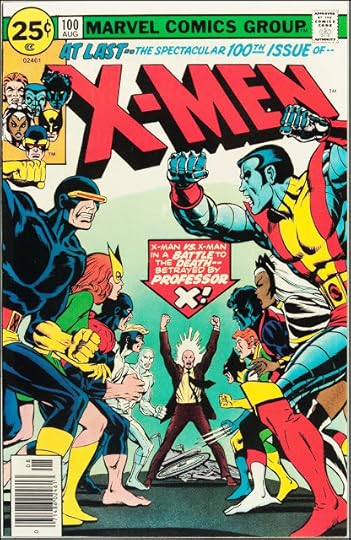

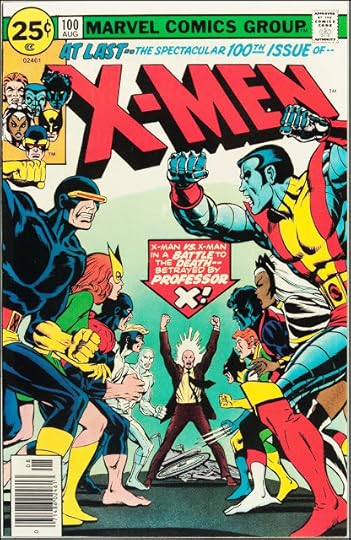

Here's a cover Roy complained about: "For what must be the hundredth time…the cover copy was screwed up…"

"For what must be the hundredth time…the cover copy was screwed up…"

He points out that "Norse" was indicated to be as large as "Inca," for one thing. He also has issues with the coloring. The main complaint was that "as usual" it wasn't sent to him to check.

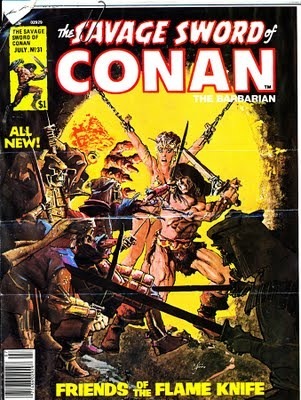

In a letter dated April 21, 1978, he encloses a printed copy of this cover:

The title on the bottom was supposed to read "FIENDS of the FLAME KNIFE," not "Friends." Roy again mentions that "only sporadic" covers arrive for him to check, and that a half dozen errors in cover copy have crept by in a period of a few months.

The title on the bottom was supposed to read "FIENDS of the FLAME KNIFE," not "Friends." Roy again mentions that "only sporadic" covers arrive for him to check, and that a half dozen errors in cover copy have crept by in a period of a few months.

There are more letters specifically about cover problems, but you get the drift.

More letters citing missing text pages, including one for an issue in which the story contains a footnote referring readers to the text page that isn't there.

There's a note about dropped letter columns including a few angry words about the bookkeeping department. Seems that when a letters page Roy delivered was, for some reason, no fault of his, left out, the bookkeeping people deducted his payment for it from his next check! P.S., in the same letter, Roy points out that the bookkeeping department consistently misspelled its own name for years ("bookeeping").

There are many more letters regarding many mistakes in many issues. Art "corrections" that change things from right to wrong. Missing or unaccountably changed copy. Everything imaginable.

The Grand No-Prize goes to Savage Sword of Conan #38. First, the proofs were sent to Roy too late, by regular mail and to the wrong address. Mistakes in the book include, but are not limited to:

A map on page four that shouldn't be there, and is, in fact, taken from a copyrighted source.

An instruction in the page description being printed as if it were actual copy: "INTRODUCTORY BOX," page 56.

Missing halftones.

Design nightmares, poor layouts.

Misspelled names.

And more, but the corker is this one….

Commas drawn in by hand in a typeset text piece. Talk about amateurish….

If anyone out there thinks I'm citing these things to belittle them or make them seem petty, you are so wrong. I don't see things like the above as insignificant. NO PROFESSIONAL PUBLISHING HOUSE SHOULD ALLOW CRAP LIKE THAT TO MAKE IT INTO PRINT! It is pathetic. It is unacceptable. Things like that drive me crazy. Roy may be fussbudget #1, but I'm first runner up, and neither of us is Miss Congeniality to the incompetent nitwits who screw up.

It just ruins your work. You don't need extra copies of issues that have idiocies like that in them, because you're certainly not going to give any away as samples.

P.S. The examples cited above are only some of the ones Roy wrote letters about, and the ones he wrote letters about were only a small portion of the grand total. I can absolutely assure you that Roy had a telephone and wasn't afraid to use it.

The above was our, Marvel's fault, or, if you wish, my fault, going with the buck-stops-here theory.

I tried to help the situation by assigning a staff assistant editor to be Roy's on-site agent, to look after his books and follow up for him. I picked Ralph Macchio. That didn't work out so well. See "Friends of the Flame Knife," above. I tried Mark Gruenwald. Strike two.

So, Roy had legitimate issues with the quality of Marvel's editorial and art production effort. So did I.

Anyway….

You're probably wondering, what were my issues with him? Or, more accurately, with his being a writer/editor.

Lateness. Roy was chronically late delivering his work. Roy's problems keeping on schedule caused major headaches. Not all of the art production and proofreading/corrections failures were caused by the lateness of his books, but it certainly didn't help. I will add that Roy was obligated to deliver over 100 pages of script a month, in addition to all the text pages, cover designs, cover copy, line-ups and miscellaneous work; in addition also to the administrative tasks that were part of his arrangement—things like inventory reports and dealing with artists. That's a tremendous amount of work. He was merely late. Anyone else except Stan in his prime would have keeled over dead in a month.

Occasional lapses in judgment with regard to content. The only one of significance I can recall in the comics was the "whipping scene" in Savage Sword #41, for which we drew some heat. Of greater concern to me were a few discussions about his personal life in text features that I thought were inappropriate.

Using other writers. Apparently, Roy thought it was okay to do so. I saw nothing in his agreements that said so, and Marvel was paying for him, not someone who wasn't nearly as good as him, whether or not he tried to fix up what they wrote. In one letter, Roy admitted that one such writer's story was "…almost unintelligible as a plotline."

Huge workload or not, the quality of the work Roy did personally was never, ever an issue. His stories were solid and his writing was top shelf. I had nothing but admiration for his creativity and skill.

Making a poor choice once in a blue moon considering the vast number of issues Roy produced is evidence of humanity, not incompetence or lack of discernment.

Farming out work to other writers…? I don't know….

Other problems inherent generally in the writer/editor concept, I think, include:

Coordinating the in-house work with theirs.

Coordinating between or among writer/editors, writers and editors.

Accountability and responsibility issues.

Gaps in process management.

Practical matters.

In Roy's case, I had no real concern about the quality of the writing. As has been said here many times, if you can get a guy who doesn't need any creative handholding, who can write and gets it right, that's ideal. That's Roy. But you still have to make the words and pictures into a book.

Discussions with Roy about what would happen when his contract came up in 1980 started in more than a casual way right after Stan notified the writer/editors that I was empowered to act in his stead, which was in mid-May, 1978. Roy responded swiftly, saying that regardless of Stan's letter, he intended to proceed as always, "…with full power over the books on which I work," and would not tolerate interference.

He continued to go directly to Stan about things occasionally. I know because Stan simply passed his correspondence on to me and came to me with whatever.

Things got contentious between Roy and me a few times.

Roy spoke with a New York Times reporter, a friend of Rick Marschall's, who was doing a hatchet job on me after I fired his buddy. I took Roy's remarks to be negative and inappropriate.

Later, I removed Roy from Thor because he was terminally late. I couldn't reach him to tell him so I sent a telegram.

The telegram arrived at 10 PM his time. He called me angrily at 1:30 AM my time, at home. Nice.

I, idiotically, talked about that incident to the Comic Buyer's Guide. (See "Making a poor choice…evidence of humanity…" above.) Roy was upset.

Blah, blah, blah….

Somehow throughout, we kept making comics. He kept doing good work, kept sending in plans and ideas. I did everything I could for him.

Slowly, I improved the editorial and art production crews. We got rid of the weakest links, editors Rick Marschall, as mentioned above, eventually, smart-but-too-inexperienced Lynn Graeme, production manager Lenny Grow and others. We brought in good people: editors Louise Jones (later Simonson), Larry Hama, Archie Goodwin, Carl Potts and more; production manager Danny Crespi and some excellent art production people.

Eventually, Roy's contract came up. I had always told Roy I thought we'd be able to work something out. And, I thought I had a good scenario worked out.

The idea was to relieve Roy of the non-creative baggage, free him to do creative work and contribute editorially in every way he could or wanted to. Have an editor on site keeping track of the schedule so that problems could be dealt with at earlier stages. Have the editor on site managing all the nuts and bolts of art production and seeing to it that things were done right.

Practical matters.

That, and provide a failsafe system. An editor not to interfere with Roy, but to backstop him. In case a glitch in the story ever did crop up, or to at least raise the question of appropriateness if the equivalent of a whipping scene came along.

I almost sold him on my plan.

NEXT: "I'll Never Doubt You Again."

The tale of the contract negotiations with Roy is too long to tell in blow-by-blow detail. I'll tell you a bit of what I understand to be his side and a little of mine.

I think we both sincerely believed in the validity of our positions. I think each of us handled things badly at some points. I don't think there ever was any malice on Roy's side and there was none on mine, though Roy apparently felt otherwise sometimes.

Yesterday, I showed you a stack of contracts and drafts of same and a file full of letters from Roy. The contracts are what they are, no shocking revelations there.

The letters break down into four categories, basically:

Business stuff – regarding vouchers, contracts, schedules, policy matters and the like; also his side of any debates or controversies.

Ideas for new books, including some suggestions for other people, like Jack Kirby. Lots of ideas.

His plans for upcoming issues of each series he was working on. He was the only writer/editor to offer that courtesy. The only writer, for that matter.

Complaints about mistakes.

There were lots of the latter.

Roy's letters aren't simply business documents (as were Mike Hobson's letters regarding the Gerber script posted here a while ago). They're business related, but written person to person—one coworker to another, with informality appropriate to addressing someone you know. They weren't written for public display, and I will respect that. I will quote a passage here and there.

Here's a cover Roy complained about:

"For what must be the hundredth time…the cover copy was screwed up…"

"For what must be the hundredth time…the cover copy was screwed up…" He points out that "Norse" was indicated to be as large as "Inca," for one thing. He also has issues with the coloring. The main complaint was that "as usual" it wasn't sent to him to check.

In a letter dated April 21, 1978, he encloses a printed copy of this cover:

The title on the bottom was supposed to read "FIENDS of the FLAME KNIFE," not "Friends." Roy again mentions that "only sporadic" covers arrive for him to check, and that a half dozen errors in cover copy have crept by in a period of a few months.

The title on the bottom was supposed to read "FIENDS of the FLAME KNIFE," not "Friends." Roy again mentions that "only sporadic" covers arrive for him to check, and that a half dozen errors in cover copy have crept by in a period of a few months. There are more letters specifically about cover problems, but you get the drift.

More letters citing missing text pages, including one for an issue in which the story contains a footnote referring readers to the text page that isn't there.

There's a note about dropped letter columns including a few angry words about the bookkeeping department. Seems that when a letters page Roy delivered was, for some reason, no fault of his, left out, the bookkeeping people deducted his payment for it from his next check! P.S., in the same letter, Roy points out that the bookkeeping department consistently misspelled its own name for years ("bookeeping").

There are many more letters regarding many mistakes in many issues. Art "corrections" that change things from right to wrong. Missing or unaccountably changed copy. Everything imaginable.

The Grand No-Prize goes to Savage Sword of Conan #38. First, the proofs were sent to Roy too late, by regular mail and to the wrong address. Mistakes in the book include, but are not limited to:

A map on page four that shouldn't be there, and is, in fact, taken from a copyrighted source.

An instruction in the page description being printed as if it were actual copy: "INTRODUCTORY BOX," page 56.

Missing halftones.

Design nightmares, poor layouts.

Misspelled names.

And more, but the corker is this one….

Commas drawn in by hand in a typeset text piece. Talk about amateurish….

If anyone out there thinks I'm citing these things to belittle them or make them seem petty, you are so wrong. I don't see things like the above as insignificant. NO PROFESSIONAL PUBLISHING HOUSE SHOULD ALLOW CRAP LIKE THAT TO MAKE IT INTO PRINT! It is pathetic. It is unacceptable. Things like that drive me crazy. Roy may be fussbudget #1, but I'm first runner up, and neither of us is Miss Congeniality to the incompetent nitwits who screw up.

It just ruins your work. You don't need extra copies of issues that have idiocies like that in them, because you're certainly not going to give any away as samples.

P.S. The examples cited above are only some of the ones Roy wrote letters about, and the ones he wrote letters about were only a small portion of the grand total. I can absolutely assure you that Roy had a telephone and wasn't afraid to use it.

The above was our, Marvel's fault, or, if you wish, my fault, going with the buck-stops-here theory.

I tried to help the situation by assigning a staff assistant editor to be Roy's on-site agent, to look after his books and follow up for him. I picked Ralph Macchio. That didn't work out so well. See "Friends of the Flame Knife," above. I tried Mark Gruenwald. Strike two.

So, Roy had legitimate issues with the quality of Marvel's editorial and art production effort. So did I.

Anyway….

You're probably wondering, what were my issues with him? Or, more accurately, with his being a writer/editor.

Lateness. Roy was chronically late delivering his work. Roy's problems keeping on schedule caused major headaches. Not all of the art production and proofreading/corrections failures were caused by the lateness of his books, but it certainly didn't help. I will add that Roy was obligated to deliver over 100 pages of script a month, in addition to all the text pages, cover designs, cover copy, line-ups and miscellaneous work; in addition also to the administrative tasks that were part of his arrangement—things like inventory reports and dealing with artists. That's a tremendous amount of work. He was merely late. Anyone else except Stan in his prime would have keeled over dead in a month.

Occasional lapses in judgment with regard to content. The only one of significance I can recall in the comics was the "whipping scene" in Savage Sword #41, for which we drew some heat. Of greater concern to me were a few discussions about his personal life in text features that I thought were inappropriate.

Using other writers. Apparently, Roy thought it was okay to do so. I saw nothing in his agreements that said so, and Marvel was paying for him, not someone who wasn't nearly as good as him, whether or not he tried to fix up what they wrote. In one letter, Roy admitted that one such writer's story was "…almost unintelligible as a plotline."

Huge workload or not, the quality of the work Roy did personally was never, ever an issue. His stories were solid and his writing was top shelf. I had nothing but admiration for his creativity and skill.

Making a poor choice once in a blue moon considering the vast number of issues Roy produced is evidence of humanity, not incompetence or lack of discernment.

Farming out work to other writers…? I don't know….

Other problems inherent generally in the writer/editor concept, I think, include:

Coordinating the in-house work with theirs.

Coordinating between or among writer/editors, writers and editors.

Accountability and responsibility issues.

Gaps in process management.

Practical matters.

In Roy's case, I had no real concern about the quality of the writing. As has been said here many times, if you can get a guy who doesn't need any creative handholding, who can write and gets it right, that's ideal. That's Roy. But you still have to make the words and pictures into a book.

Discussions with Roy about what would happen when his contract came up in 1980 started in more than a casual way right after Stan notified the writer/editors that I was empowered to act in his stead, which was in mid-May, 1978. Roy responded swiftly, saying that regardless of Stan's letter, he intended to proceed as always, "…with full power over the books on which I work," and would not tolerate interference.

He continued to go directly to Stan about things occasionally. I know because Stan simply passed his correspondence on to me and came to me with whatever.

Things got contentious between Roy and me a few times.

Roy spoke with a New York Times reporter, a friend of Rick Marschall's, who was doing a hatchet job on me after I fired his buddy. I took Roy's remarks to be negative and inappropriate.

Later, I removed Roy from Thor because he was terminally late. I couldn't reach him to tell him so I sent a telegram.

The telegram arrived at 10 PM his time. He called me angrily at 1:30 AM my time, at home. Nice.

I, idiotically, talked about that incident to the Comic Buyer's Guide. (See "Making a poor choice…evidence of humanity…" above.) Roy was upset.

Blah, blah, blah….

Somehow throughout, we kept making comics. He kept doing good work, kept sending in plans and ideas. I did everything I could for him.

Slowly, I improved the editorial and art production crews. We got rid of the weakest links, editors Rick Marschall, as mentioned above, eventually, smart-but-too-inexperienced Lynn Graeme, production manager Lenny Grow and others. We brought in good people: editors Louise Jones (later Simonson), Larry Hama, Archie Goodwin, Carl Potts and more; production manager Danny Crespi and some excellent art production people.

Eventually, Roy's contract came up. I had always told Roy I thought we'd be able to work something out. And, I thought I had a good scenario worked out.

The idea was to relieve Roy of the non-creative baggage, free him to do creative work and contribute editorially in every way he could or wanted to. Have an editor on site keeping track of the schedule so that problems could be dealt with at earlier stages. Have the editor on site managing all the nuts and bolts of art production and seeing to it that things were done right.

Practical matters.

That, and provide a failsafe system. An editor not to interfere with Roy, but to backstop him. In case a glitch in the story ever did crop up, or to at least raise the question of appropriateness if the equivalent of a whipping scene came along.

I almost sold him on my plan.

NEXT: "I'll Never Doubt You Again."

Published on August 16, 2011 19:02

August 15, 2011

Writer/Editors – Part 3

"How Could You Let This Happen?" or, "What Do You MEAN Roy's Quitting?"

Roy Thomas leaving Marvel? Unthinkable. Almost as unthinkable as Stan Lee leaving Marvel. Seriously. In 1980, it was that big a deal.

If Roy were leaving to go write movies or TV shows or novels, well, that would be traumatic but manageable. You'd give him the big send-off, lots of congratulations, plug his new work incessantly and soldier on without him. The association with him and his newfound success would be good, in and of itself. If he became the next William Goldman or Michael Crichton all the better. Maybe he'd fondly remember Marvel and give us a boost in Hollywood, or come back now and then to do a highly promotable, high profile special project for old times' sake. If he succeeded on larger stages, wouldn't that bring more talent to our door…? New writers who saw Marvel as a legitimate step en route to a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame?

But leaving to go to another comics publisher? Unthinkable.

But it came to that.

Some believe, or would have you believe, that because he was a writer/editor and I didn't like it I drove Roy out. Steve Gerber and Marv Wolfman, too, for that matter.

That works very well with the Shooter is a megalomaniac theory. I think comics people love to think in terms of heroes and villains. It's easier to picture me in my dark fortress scheming to satisfy my monstrous ego, cackling "Power must be mine alone!" rather than me in my small, dingy office trying to do my job well and honorably. Easier to imagine the writer/editors as noble, superhuman defenders of their rights and freedom rather than as contract writers, good but still mortal, working with characters that are not theirs, but belong to or are licensed by the company.

And of course, any conflict that arose never had anything to do with the ego of a writer/editor.

They were doing work for hire. That means that the writer has no "rights" either in the ownership sense or the moral sense and no "freedom." Doing work for hire on characters somebody else owns comes with limitations. Strict limitations at places like Disney, Hanna-Barbera and almost every house with proprietary characters. Marvel's limitations were far less stringent than most, but applicable to all creators, whether they were writer/editors or not.

So…the rights and freedom these noble superhumans were defending were the rights to do…what? The freedom to do…what? More on that below.

I believed that writer/editor status for the people in question, at least in the situation in question, was a bad idea. I was not alone.

President Jim Galton was never happy with the idea. He thought it was crazy, in fact.

Galton didn't know much about comic books. I guess he figured this writer/editor business was some quirky comics thing he didn't grok (not that he would have a clue what "grok" means). He went along with it because the practice of granting former EIC's that status was entrenched before he arrived at Marvel, and because Stan convinced him it was necessary.

Stan agreed to it in the first place, in Roy's case, years earlier, because as de facto writer/editor himself for many years, Stan didn't see it as intrinsically bad, there really wasn't much of an editorial organization in place at the time and it was Roy, after all.

Once Roy was established as a writer/editor and the world failed to end, it didn't seem unreasonable to make the next departing EIC, Len Wein, a writer/editor, too. And then, the precedent was truly set. How could you not make Marv a writer/editor if Roy and Len were? It became S.O.P. Why not Gerry Conway, when it was his turn? How could you deny the status to him without the implication that he wasn't as good as those who came before him? And, was Archie Goodwin chopped liver? I think not.

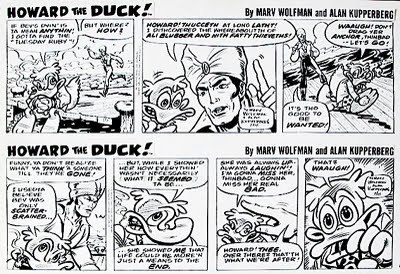

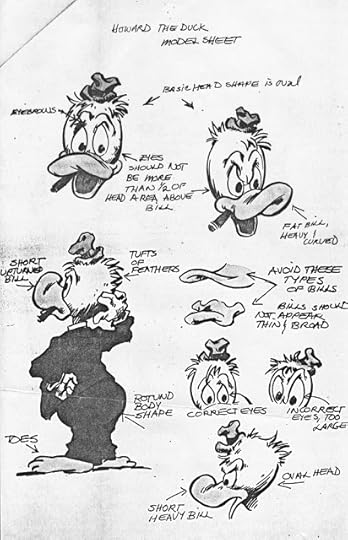

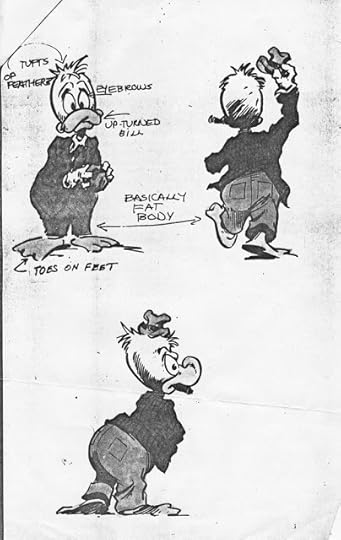

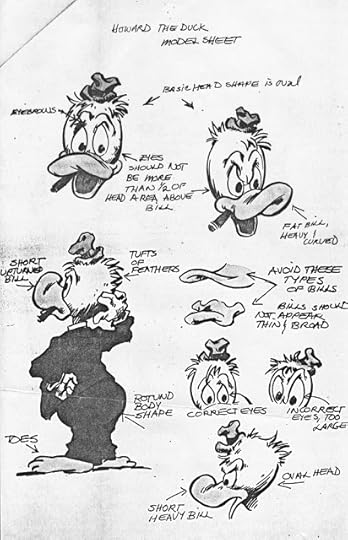

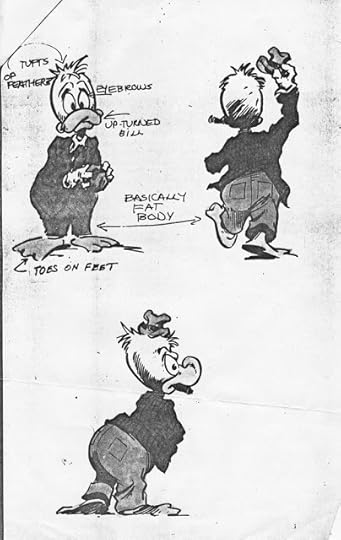

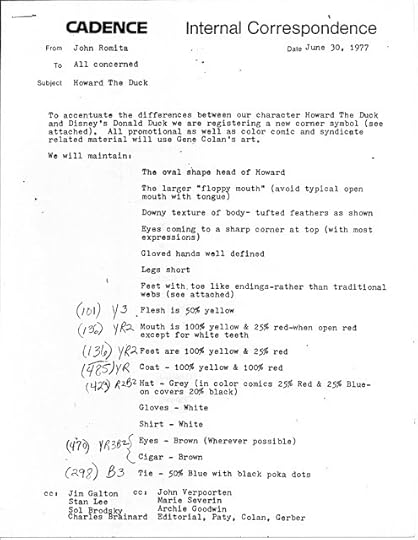

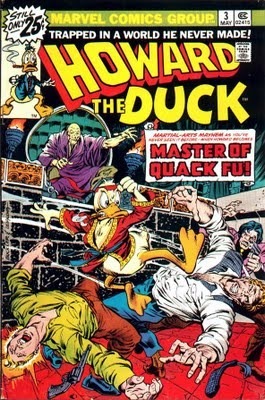

The odd duck, if you will, was Steve Gerber, the only writer/editor who wasn't a former EIC. However, along with Val Mayerik, he had created Howard the Duck. Howard was marginal as a publishing property but had developed some cult favorite status that extended as far as Hollywood, and therefore had licensing potential. Somehow, Steve parlayed that into writer/editor status under Archie's EIC watch.

As recounted in the previous post, though he had started the writer/editor thing, by 1978, Stan started having serious doubts about the writer/editor concept.

There were some comments to the previous posts in this series that cited issues or runs of issues written by writer/editors that were good. The correspondents suggested that somehow these successful efforts proved that sometimes having a writer/editor is perfectly fine. Sometimes an editor is needed, sometimes not.

With all due respect, their books should have been good. All of them, not just some select list. They're supposed to be the best.

Regarding that particular example, first of all, I was the editor (as "associate editor," i.e., line editor) who edited #3-8. The three (!) Editors in Chief during that span, Marv, Gerry and Archie, didn't see those books till they were in print and may not have read them even then. As I recounted, I made a pretty good catch on #3 and a number of small ones on later issues. Furthermore, though Gerber was writer/editor starting with #9, it made no difference except that Gerber got an extra $100 bucks an issue for being editor. Maybe someone didn't tell Production Manager John Verpoorten that the books were no longer supposed to pass under my blue pencil, but they did. I still edited the books, all the way through the issue numbers in the low 20's. Gerber's writing was mostly very clean and tight. I still caught a few things here and there. I still went over the glitches with Steve. We still never had any problems. Nothing changed.

The quality of the script is not, by a long shot, the only responsibility of an editor. So, who's doing the rest of it and what if problems crop up? Or, what if the writer/editor himself is the problem? See below.

And if there was a problem with a writer/editor, the only thing you could do was run and tell Stan on them. Stan who was busy with his own projects. Stan who wasn't in the loop. Stan who didn't want to get involved in editorial hassles. At all. Ever. Great.

Anyway….

Len left for DC Comics before I became EIC. Gerry also left for DC before I took office. When I came in, the remaining writer/editors were Roy, Marv, Archie and Steve.

Let's talk about the easy ones first.

Steve Gerber left not long after I started as EIC. One contributing factor was his removal from the HTD newspaper strip for being consistently, badly late. That's a capital crime. You can't be late on a strip. He was angry about being ousted, though, which led in part to: factor number two: he was threatening to sue Marvel. If you're threatening to sue your employer, they probably aren't going to keep paying you so you can pay your lawyers. He was fired. I couldn't have prevented it if I had tried.

Archie was a pleasure to deal with. When he delivered his scripts he either brought them to me or gave them to John Verpoorten to give to me. I checked them because he wanted me to. They were impeccable. I couldn't even find a balloon placement to improve. On only a few occasions, I found a typo. Once, Archie used the word "trooper" to mean a reliable, hard-working stick-to-it type. I told him it should be "trouper." He thanked me. That was the biggest catch I made. Because he lived in town, Archie could be, and was hands on with cover designs and other responsibilities. The only problem with Archie was that he was slow and always late. But he was reasonable about dealing with that. Archie stopped being a writer/editor in late 1979 when he accepted a staff position as editor of EPIC Illustrated Magazine.

Which brings us to Marv.

Back in those pre-royalty days, creators were paid page-rate only. I was working on putting in place a number of benefits and incentives, and had succeeded to some extent, but the basic compensation for comics creative work was still X dollars per page. And the X wasn't very big. The top page rate for writing in those days was in the mid-$20 range. One had to write a lot of pages to earn a living.

Marv gave his best efforts to a few, favorite books. Tomb of Dracula, especially. The favorites were his build-the-rep books. The others were the pay-the-rent books. It showed, in my opinion.

So, what "rights," what "freedom" was Marv defending by insisting that he be a writer/editor? The right to crank out enough pages with words on them, in addition to his writing for his trophy books, to meet his four-book a month (as I recall) quota? The freedom not to be delayed or inconvenienced by an editor who demanded Marv's best work on all his books?

Those were tough times for comic book creators. Marv wasn't the only one feeling economic pressure to produce. For too many creators, including some superstar talents and hall-of-famers, it was all about lots of pages to voucher not quality.

Eventually, we made things better. Too late to change the equation re: Marv.

As I stated before, Marv needed an editor anyway to help him sort out his language problems, help him with story organization and avoid those logical tangles he got himself into sometimes, especially while cranking.

I offered Marv the best deal ever offered a writer by Marvel. The money was so good we would have had to give Roy a large page rate increase, too, since he had a nobody-gets-paid-more-than-me clause in his contract. But I said no writer/editor provision.

Marv insisted upon being a writer/editor. I stuck to my guns.

Marv, of course, had an offer from DC, and took it. As I understand it, he wasn't a writer/editor there either, at first, but I suppose sticking to his guns, sort of, was necessary to save face.

Sort of.

I gather that with the success of Teen Titans, which he co-created with George Pérez, he gained some clout and eventually had some kind of writer/editor status there. Right?

Anyway, he told everyone who would listen that I was the bad guy, I lied to him, etc. By then I was used to being shot at, so no big deal. I didn't lie to him, by the way. I always told him I'd do my best to work something out, and I did. The deal I offered him would have kept him involved in the parts of the editor job at which he was exceptionally good, and paid him for same. That wasn't good enough.

Which brings us to Roy.

He's a whole post by himself. Not for the reasons you think.

I really thought Roy and I had reached an agreement. Actually, we did. Then Roy changed his mind.

Then I got a call from upstairs, from Galton. He said Roy had called him and told him he was quitting to go to DC. And then Galton said, words to the effect: "How Could You Let This Happen?"

Details tomorrow.

By the way, the Roy story is very clear in my mind, largely because I have, and have reread all the iterations of his contracts from 1974 and 1976, plus amendments to same, all versions of the proposed 1980 contract, every letter Roy ever sent to me and many letters he sent to Stan and Sol Brodsky from that time and earlier. Stan passed them along to me.

So, stay tuned.

NEXT: "I'll Never Doubt You Again."

NEXT: "I'll Never Doubt You Again."

Roy Thomas leaving Marvel? Unthinkable. Almost as unthinkable as Stan Lee leaving Marvel. Seriously. In 1980, it was that big a deal.

If Roy were leaving to go write movies or TV shows or novels, well, that would be traumatic but manageable. You'd give him the big send-off, lots of congratulations, plug his new work incessantly and soldier on without him. The association with him and his newfound success would be good, in and of itself. If he became the next William Goldman or Michael Crichton all the better. Maybe he'd fondly remember Marvel and give us a boost in Hollywood, or come back now and then to do a highly promotable, high profile special project for old times' sake. If he succeeded on larger stages, wouldn't that bring more talent to our door…? New writers who saw Marvel as a legitimate step en route to a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame?

But leaving to go to another comics publisher? Unthinkable.

But it came to that.

Some believe, or would have you believe, that because he was a writer/editor and I didn't like it I drove Roy out. Steve Gerber and Marv Wolfman, too, for that matter.

That works very well with the Shooter is a megalomaniac theory. I think comics people love to think in terms of heroes and villains. It's easier to picture me in my dark fortress scheming to satisfy my monstrous ego, cackling "Power must be mine alone!" rather than me in my small, dingy office trying to do my job well and honorably. Easier to imagine the writer/editors as noble, superhuman defenders of their rights and freedom rather than as contract writers, good but still mortal, working with characters that are not theirs, but belong to or are licensed by the company.

And of course, any conflict that arose never had anything to do with the ego of a writer/editor.

They were doing work for hire. That means that the writer has no "rights" either in the ownership sense or the moral sense and no "freedom." Doing work for hire on characters somebody else owns comes with limitations. Strict limitations at places like Disney, Hanna-Barbera and almost every house with proprietary characters. Marvel's limitations were far less stringent than most, but applicable to all creators, whether they were writer/editors or not.

So…the rights and freedom these noble superhumans were defending were the rights to do…what? The freedom to do…what? More on that below.

I believed that writer/editor status for the people in question, at least in the situation in question, was a bad idea. I was not alone.

President Jim Galton was never happy with the idea. He thought it was crazy, in fact.

Galton didn't know much about comic books. I guess he figured this writer/editor business was some quirky comics thing he didn't grok (not that he would have a clue what "grok" means). He went along with it because the practice of granting former EIC's that status was entrenched before he arrived at Marvel, and because Stan convinced him it was necessary.

Stan agreed to it in the first place, in Roy's case, years earlier, because as de facto writer/editor himself for many years, Stan didn't see it as intrinsically bad, there really wasn't much of an editorial organization in place at the time and it was Roy, after all.

Once Roy was established as a writer/editor and the world failed to end, it didn't seem unreasonable to make the next departing EIC, Len Wein, a writer/editor, too. And then, the precedent was truly set. How could you not make Marv a writer/editor if Roy and Len were? It became S.O.P. Why not Gerry Conway, when it was his turn? How could you deny the status to him without the implication that he wasn't as good as those who came before him? And, was Archie Goodwin chopped liver? I think not.

The odd duck, if you will, was Steve Gerber, the only writer/editor who wasn't a former EIC. However, along with Val Mayerik, he had created Howard the Duck. Howard was marginal as a publishing property but had developed some cult favorite status that extended as far as Hollywood, and therefore had licensing potential. Somehow, Steve parlayed that into writer/editor status under Archie's EIC watch.

As recounted in the previous post, though he had started the writer/editor thing, by 1978, Stan started having serious doubts about the writer/editor concept.

There were some comments to the previous posts in this series that cited issues or runs of issues written by writer/editors that were good. The correspondents suggested that somehow these successful efforts proved that sometimes having a writer/editor is perfectly fine. Sometimes an editor is needed, sometimes not.

With all due respect, their books should have been good. All of them, not just some select list. They're supposed to be the best.

Czeskleba said, "…there doesn't seem to be a lot of difference between the issues edited by Archie Goodwin (#1-8) and the ones Gerber edited himself (the rest of his run)."

Regarding that particular example, first of all, I was the editor (as "associate editor," i.e., line editor) who edited #3-8. The three (!) Editors in Chief during that span, Marv, Gerry and Archie, didn't see those books till they were in print and may not have read them even then. As I recounted, I made a pretty good catch on #3 and a number of small ones on later issues. Furthermore, though Gerber was writer/editor starting with #9, it made no difference except that Gerber got an extra $100 bucks an issue for being editor. Maybe someone didn't tell Production Manager John Verpoorten that the books were no longer supposed to pass under my blue pencil, but they did. I still edited the books, all the way through the issue numbers in the low 20's. Gerber's writing was mostly very clean and tight. I still caught a few things here and there. I still went over the glitches with Steve. We still never had any problems. Nothing changed.

The quality of the script is not, by a long shot, the only responsibility of an editor. So, who's doing the rest of it and what if problems crop up? Or, what if the writer/editor himself is the problem? See below.

And if there was a problem with a writer/editor, the only thing you could do was run and tell Stan on them. Stan who was busy with his own projects. Stan who wasn't in the loop. Stan who didn't want to get involved in editorial hassles. At all. Ever. Great.

Anyway….

Len left for DC Comics before I became EIC. Gerry also left for DC before I took office. When I came in, the remaining writer/editors were Roy, Marv, Archie and Steve.

Let's talk about the easy ones first.

Steve Gerber left not long after I started as EIC. One contributing factor was his removal from the HTD newspaper strip for being consistently, badly late. That's a capital crime. You can't be late on a strip. He was angry about being ousted, though, which led in part to: factor number two: he was threatening to sue Marvel. If you're threatening to sue your employer, they probably aren't going to keep paying you so you can pay your lawyers. He was fired. I couldn't have prevented it if I had tried.

Archie was a pleasure to deal with. When he delivered his scripts he either brought them to me or gave them to John Verpoorten to give to me. I checked them because he wanted me to. They were impeccable. I couldn't even find a balloon placement to improve. On only a few occasions, I found a typo. Once, Archie used the word "trooper" to mean a reliable, hard-working stick-to-it type. I told him it should be "trouper." He thanked me. That was the biggest catch I made. Because he lived in town, Archie could be, and was hands on with cover designs and other responsibilities. The only problem with Archie was that he was slow and always late. But he was reasonable about dealing with that. Archie stopped being a writer/editor in late 1979 when he accepted a staff position as editor of EPIC Illustrated Magazine.

Which brings us to Marv.

Back in those pre-royalty days, creators were paid page-rate only. I was working on putting in place a number of benefits and incentives, and had succeeded to some extent, but the basic compensation for comics creative work was still X dollars per page. And the X wasn't very big. The top page rate for writing in those days was in the mid-$20 range. One had to write a lot of pages to earn a living.

Marv gave his best efforts to a few, favorite books. Tomb of Dracula, especially. The favorites were his build-the-rep books. The others were the pay-the-rent books. It showed, in my opinion.

So, what "rights," what "freedom" was Marv defending by insisting that he be a writer/editor? The right to crank out enough pages with words on them, in addition to his writing for his trophy books, to meet his four-book a month (as I recall) quota? The freedom not to be delayed or inconvenienced by an editor who demanded Marv's best work on all his books?

Those were tough times for comic book creators. Marv wasn't the only one feeling economic pressure to produce. For too many creators, including some superstar talents and hall-of-famers, it was all about lots of pages to voucher not quality.

Eventually, we made things better. Too late to change the equation re: Marv.

As I stated before, Marv needed an editor anyway to help him sort out his language problems, help him with story organization and avoid those logical tangles he got himself into sometimes, especially while cranking.

I offered Marv the best deal ever offered a writer by Marvel. The money was so good we would have had to give Roy a large page rate increase, too, since he had a nobody-gets-paid-more-than-me clause in his contract. But I said no writer/editor provision.

Marv insisted upon being a writer/editor. I stuck to my guns.

Marv, of course, had an offer from DC, and took it. As I understand it, he wasn't a writer/editor there either, at first, but I suppose sticking to his guns, sort of, was necessary to save face.

Sort of.

I gather that with the success of Teen Titans, which he co-created with George Pérez, he gained some clout and eventually had some kind of writer/editor status there. Right?

Anyway, he told everyone who would listen that I was the bad guy, I lied to him, etc. By then I was used to being shot at, so no big deal. I didn't lie to him, by the way. I always told him I'd do my best to work something out, and I did. The deal I offered him would have kept him involved in the parts of the editor job at which he was exceptionally good, and paid him for same. That wasn't good enough.

Which brings us to Roy.

He's a whole post by himself. Not for the reasons you think.

I really thought Roy and I had reached an agreement. Actually, we did. Then Roy changed his mind.

Then I got a call from upstairs, from Galton. He said Roy had called him and told him he was quitting to go to DC. And then Galton said, words to the effect: "How Could You Let This Happen?"

Details tomorrow.

By the way, the Roy story is very clear in my mind, largely because I have, and have reread all the iterations of his contracts from 1974 and 1976, plus amendments to same, all versions of the proposed 1980 contract, every letter Roy ever sent to me and many letters he sent to Stan and Sol Brodsky from that time and earlier. Stan passed them along to me.

So, stay tuned.

NEXT: "I'll Never Doubt You Again."

NEXT: "I'll Never Doubt You Again."

Published on August 15, 2011 17:04

August 11, 2011

Writer/Editors – Part 2

First, This

Sorry about not posting for the last two days. Tuesday, I had to go to the city for a meeting and when I arrived home I discovered that my hot water heater had sprung a leak. There was a flood in my place and a worse one in the apartment below mine. What a mess.

It took until late Wednesday afternoon for order and hot water have been restored here, like it never even happened.

Eventually the damage downstairs will be fixed. Someone other than me will deal with that mess, and insurance will pay for it.

By the way, the flood did not reach the living room where all of my files and unsorted boxes are. Nothing irreplaceable was damaged.

So, on with the show. Finally.

Writer/Editors – Part 2

The Problem, Or an Example, at Least

One day, Stan suddenly appeared at my door. He seemed agitated. Very agitated. He said, words to the effect, "How could you let this happen?!"

This was sometime in the spring of 1978.

Every once in a while, Stan would come across something that disturbed him and come into my office to discuss it. I knew this was a DEFCON 1 situation because he closed the door behind him.

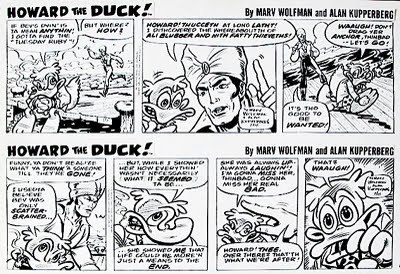

He had a bunch of photocopies in one hand. He literally tossed them onto my desk in front of me. They were copies of the previous few weeks of the Howard the Duck syndicated strip written by Marv Wolfman. Steve Gerber had been writing the strip previously, of course, but had been replaced, mostly because he was consistently, disastrously late.

This was the first time Stan had read any of the strips since Gerber was gone.

I'm not going to try to reconstruct all of what Stan said. Suffice it to say he hated it.

As I believe I've said earlier in this blog, Stan had a special reverence for syndicated strips. And "real" magazines. Not that he didn't love the comic books, it's just that when he was a kid, the strips were huge and prestigious while the comic book business was where one scratched out a living until his or her strip got picked up by a syndicate. Anyone who aspired to becoming a syndicated strip creator changed his or her name for work in lowly comic books, hence, Stanley Leiber became Stan Lee. Same logic applied if one hoped to publish a "real" magazine or write the Great American Novel. Never mind that comic books had made Stan a cultural icon, and he had brought comics to unprecedented status in the New Cultural Order. He never lost his veneration of syndicated strips.

So, a strip created by Marvel that was less than wonderful was anathema to Stan. And he found the HTD strips he'd just read far less than wonderful.

One part of Stan's anguished tirade I will quote. He said, "He can't write!" Meaning Marv. I said I knew. Stan persisted. He thought I didn't grasp what he was saying. So, he said it several times, as emphatically as I've ever heard him say anything. This is a quote: "Don't you see?! This makes no sense! It's illiterate! He can't write!"

I told Stan that, yes, I understood what he was saying. I knew all about Marv's problems with the English language. I knew that he often wrote too fast without thinking things through, sometimes resulting in inconsistencies, and sometimes in chaos.

If I knew, he wondered, could I allow Marv to ruin the HTD strip? Why wasn't I fixing it? Or, better, why didn't I get rid of him?

I pointed out that Stan himself had chosen Marv for the strip. And, that on Stan's recommendation, two years earlier, Marv had been made a writer/editor—which meant that, according to the terms of Marv's contract, I couldn't fix Marv's stuff. Or get rid of him. Only Stan could.

And, by the way, because President Jim Galton had asked me to come up with a job for Sol Brodsky, our "Operations V.P." who really had no significant responsibilities, I had given over handling of the syndicated strips (and other peripheral tasks) to him and hardly ever even saw them anymore before they shipped.

Stan was suddenly having one of those "oh, God, what have I done" moments. Realizing that, not only was Marv a writer/editor now because of him, but Marv had been an Editor in Chief that, he, Stan, had hired.

I asked Stan if he'd read anything of Marv's before he hired him as EIC. Stan said he'd taken Len Wein's word for the fact that Marv was a great writer, and qualified to be EIC. I pointed out that Len was Marv's best friend….

Even Len, by the way, privately, would shake his head at some of Marv's linguistic bloopers. And Marv knew at least that English wasn't his strong suit. That's why he had me read over his scripts when he was EIC and I was his associate editor. I'd catch the gaffs and he would fix them. Sometimes.

That conversation continued with me defending Marv. Marv is a unique talent. Here's what I said in a previous post:

All true. And I said as much to Stan.

I told Stan that Marv's contract was coming up in a while and that I intended to offer him a new one, best deal ever, in fact. But without the writer/editor status, or at least not in the sweeping form guaranteed in his current contract. There were/are other ways to go about it with fewer downsides.

We came to no conclusions about the HTD strip at that meeting. Stan left my room pondering.

Not long thereafter, the HTD strip was cancelled. The syndicate pulled the plug because it was failing. Just as well, given Stan's feelings.

Around the same time, mid-May, I think, Stan sent a letter to the writer editors informing them that he was designating me to act in his stead. The writer/editors, at that point were Roy Thomas, Archie Goodwin and Marv. Maybe Gerber, too.

Why?

Stan, at that point in his life, hated confrontations and controversy. I guess he'd had enough of it in earlier days when he was dealing directly, daily with the artists, writers and other creative types. He was happy to throw me into the breach. Believe what you wish, but I hate confrontation, too. But, I realized if it unavoidably came to that, it was part of the job. I accepted being in the breach.

It was practical. Stan was pretty much out of the day-to-day publishing loop. As things stood previously, I'd have to bring him up to speed on any problems or issues with writer/editors that arose then he'd have to do the confronting. Why not just let me handle it, given point 1 and the fact that….

Stan trusted me.

Why?

Stan had become my biggest fan and supporter. He used to call me "Marvel's entire editor." Roy said once in a letter to Stan that I was Stan's "new, fair-haired boy." I guess Roy was the old one.

Why?

Because once I'd started getting us on schedule, started making a little progress on improving the art and stories, seemed to be handling crises like the maelstrom over the new copyright law well.

And especially because he knew I had some chops and that my creative inclinations were simpatico with his.

Anyway….

The HTD strip thing wasn't the only thing that raised issues to do with writer/editors. Even back when I was associate editor, when Stan went over the make-readies with me, he'd occasionally come across things that disturbed him in writer/editor books. Even Roy's generally excellent efforts, sometimes. He'd ask me, "How could you let this happen?" I'd point out that I had no power to do anything about it. He'd say something about speaking with then-EIC Archie Goodwin about it, but whether he did or not, nothing ever changed.

Until the declaration that I was the new sheriff.

The first thing that changed was my popularity among writer/editors.

Stay tuned.

MONDAY OR SOONER, MAYBE: "How Could You Let This Happen?" or, "What Do You MEAN Roy's Quitting?"

Sorry about not posting for the last two days. Tuesday, I had to go to the city for a meeting and when I arrived home I discovered that my hot water heater had sprung a leak. There was a flood in my place and a worse one in the apartment below mine. What a mess.

It took until late Wednesday afternoon for order and hot water have been restored here, like it never even happened.

Eventually the damage downstairs will be fixed. Someone other than me will deal with that mess, and insurance will pay for it.

By the way, the flood did not reach the living room where all of my files and unsorted boxes are. Nothing irreplaceable was damaged.

So, on with the show. Finally.

Writer/Editors – Part 2

The Problem, Or an Example, at Least

One day, Stan suddenly appeared at my door. He seemed agitated. Very agitated. He said, words to the effect, "How could you let this happen?!"

This was sometime in the spring of 1978.

Every once in a while, Stan would come across something that disturbed him and come into my office to discuss it. I knew this was a DEFCON 1 situation because he closed the door behind him.

He had a bunch of photocopies in one hand. He literally tossed them onto my desk in front of me. They were copies of the previous few weeks of the Howard the Duck syndicated strip written by Marv Wolfman. Steve Gerber had been writing the strip previously, of course, but had been replaced, mostly because he was consistently, disastrously late.

This was the first time Stan had read any of the strips since Gerber was gone.

I'm not going to try to reconstruct all of what Stan said. Suffice it to say he hated it.

As I believe I've said earlier in this blog, Stan had a special reverence for syndicated strips. And "real" magazines. Not that he didn't love the comic books, it's just that when he was a kid, the strips were huge and prestigious while the comic book business was where one scratched out a living until his or her strip got picked up by a syndicate. Anyone who aspired to becoming a syndicated strip creator changed his or her name for work in lowly comic books, hence, Stanley Leiber became Stan Lee. Same logic applied if one hoped to publish a "real" magazine or write the Great American Novel. Never mind that comic books had made Stan a cultural icon, and he had brought comics to unprecedented status in the New Cultural Order. He never lost his veneration of syndicated strips.

So, a strip created by Marvel that was less than wonderful was anathema to Stan. And he found the HTD strips he'd just read far less than wonderful.

One part of Stan's anguished tirade I will quote. He said, "He can't write!" Meaning Marv. I said I knew. Stan persisted. He thought I didn't grasp what he was saying. So, he said it several times, as emphatically as I've ever heard him say anything. This is a quote: "Don't you see?! This makes no sense! It's illiterate! He can't write!"

I told Stan that, yes, I understood what he was saying. I knew all about Marv's problems with the English language. I knew that he often wrote too fast without thinking things through, sometimes resulting in inconsistencies, and sometimes in chaos.

If I knew, he wondered, could I allow Marv to ruin the HTD strip? Why wasn't I fixing it? Or, better, why didn't I get rid of him?

I pointed out that Stan himself had chosen Marv for the strip. And, that on Stan's recommendation, two years earlier, Marv had been made a writer/editor—which meant that, according to the terms of Marv's contract, I couldn't fix Marv's stuff. Or get rid of him. Only Stan could.

And, by the way, because President Jim Galton had asked me to come up with a job for Sol Brodsky, our "Operations V.P." who really had no significant responsibilities, I had given over handling of the syndicated strips (and other peripheral tasks) to him and hardly ever even saw them anymore before they shipped.

Stan was suddenly having one of those "oh, God, what have I done" moments. Realizing that, not only was Marv a writer/editor now because of him, but Marv had been an Editor in Chief that, he, Stan, had hired.

I asked Stan if he'd read anything of Marv's before he hired him as EIC. Stan said he'd taken Len Wein's word for the fact that Marv was a great writer, and qualified to be EIC. I pointed out that Len was Marv's best friend….

Even Len, by the way, privately, would shake his head at some of Marv's linguistic bloopers. And Marv knew at least that English wasn't his strong suit. That's why he had me read over his scripts when he was EIC and I was his associate editor. I'd catch the gaffs and he would fix them. Sometimes.

That conversation continued with me defending Marv. Marv is a unique talent. Here's what I said in a previous post:

Marv is a brilliant creator. He's an idea man. He can truly create. Many can create things out of other things, synthesis. Marv often creates entirely new things, genesis. That's rare. His writing at its best is fresh, surprising, unpredictable and intriguing. There's a spontaneity to it that's wonderful and engaging. Spontaneity livens up his dialogue. People talk in a crazy stuff-popping-out-of-their-heads way just like real people often do. He has a gift for character.

All that said, he has some problems with the language. He mangles grammar. He misuses words. Once he used "noisome" as if it meant loud. It was in a caption. One can excuse many things in dialogue as the mistakes of the character's making, but the captions ought to be right. Marv argued that most people think noisome means loud, and it went to press that way.

When not at his best, Marv's spontaneity becomes lack of planning and confusion. Sparkling dialogue becomes glib patter headed nowhere.

And, by the way, with his knack for coming up with words, Marv would be the world champion Scrabble player if he could spell.

All true. And I said as much to Stan.

I told Stan that Marv's contract was coming up in a while and that I intended to offer him a new one, best deal ever, in fact. But without the writer/editor status, or at least not in the sweeping form guaranteed in his current contract. There were/are other ways to go about it with fewer downsides.

We came to no conclusions about the HTD strip at that meeting. Stan left my room pondering.

Not long thereafter, the HTD strip was cancelled. The syndicate pulled the plug because it was failing. Just as well, given Stan's feelings.

Around the same time, mid-May, I think, Stan sent a letter to the writer editors informing them that he was designating me to act in his stead. The writer/editors, at that point were Roy Thomas, Archie Goodwin and Marv. Maybe Gerber, too.

Why?

Stan, at that point in his life, hated confrontations and controversy. I guess he'd had enough of it in earlier days when he was dealing directly, daily with the artists, writers and other creative types. He was happy to throw me into the breach. Believe what you wish, but I hate confrontation, too. But, I realized if it unavoidably came to that, it was part of the job. I accepted being in the breach.

It was practical. Stan was pretty much out of the day-to-day publishing loop. As things stood previously, I'd have to bring him up to speed on any problems or issues with writer/editors that arose then he'd have to do the confronting. Why not just let me handle it, given point 1 and the fact that….

Stan trusted me.

Why?

Stan had become my biggest fan and supporter. He used to call me "Marvel's entire editor." Roy said once in a letter to Stan that I was Stan's "new, fair-haired boy." I guess Roy was the old one.

Why?

Because once I'd started getting us on schedule, started making a little progress on improving the art and stories, seemed to be handling crises like the maelstrom over the new copyright law well.

And especially because he knew I had some chops and that my creative inclinations were simpatico with his.

Anyway….

The HTD strip thing wasn't the only thing that raised issues to do with writer/editors. Even back when I was associate editor, when Stan went over the make-readies with me, he'd occasionally come across things that disturbed him in writer/editor books. Even Roy's generally excellent efforts, sometimes. He'd ask me, "How could you let this happen?" I'd point out that I had no power to do anything about it. He'd say something about speaking with then-EIC Archie Goodwin about it, but whether he did or not, nothing ever changed.

Until the declaration that I was the new sheriff.

The first thing that changed was my popularity among writer/editors.

Stay tuned.

MONDAY OR SOONER, MAYBE: "How Could You Let This Happen?" or, "What Do You MEAN Roy's Quitting?"

Published on August 11, 2011 11:07

August 8, 2011

Writer/Editors – Part 1

The Tenth Level of Hell

The first time I ever heard the term "writer/editor" was shortly after arriving for my first day as associate editor of Marvel Comics on the first working day of January, 1976. At first I thought it must mean a part-time writer who also served as an editor for other writers.

The first time I ever heard the term "writer/editor" was shortly after arriving for my first day as associate editor of Marvel Comics on the first working day of January, 1976. At first I thought it must mean a part-time writer who also served as an editor for other writers.

Nope. It meant someone who was the editor of his own work.

What?

That just baffled me. The point of having an editor is having an objective reviewer. All right, it's way more than that. Of course. An editor is supposed to be a skilled, knowledgeable, interested party whose involvement with the work is not as direct and personal as the writer's (and, in the case of comics, other creative contributors), and therefore can evaluate the work with some detachment.

Furthermore….

The job of a comics editor, as I was taught, is part business, part creative. An editor manages the business directly related to producing the comics: keeping things on schedule and being the first-line overseer of direct expenditures; governing the process of bringing together the art and editorial components and the assembly of same into a ready-to-print package. With regard to the latter, he or she is the "client" of both the art production department, which carries out the physical parts of the preparation of the package, and the manufacturing or print-production department, which produces and delivers to distributors the actual product.

Plus, an editor oversees the creative work and sees to it that the creative goals are achieved. This may include working with the writer to develop the story and contributing creatively, working with the artists to make sure the story is being told effectively, overseeing the creation of the cover and all non-comics editorial, such as letter columns, editorials, additional features, whatever.

So, the editor is something like a film producer/film director, responsible in a project management sense as well as creatively. By director, I don't mean that the editor should be the "auteur," though that has happened in comics sometimes. Usually, the editor provides some creative guidance, support and backstopping. He or she is the publisher's face to the creators.

The ideal situation is when the creators involved on a project don't need any guidance, support or backstopping. They're that good and that on the mark. Then, the editor can just watch and applaud—except for the nuts-and-bolts making it print-ready part. That never goes away.

Near ideal is when the creator enjoys or needs some collegial involvement and the editor gets to chime in a little, helping the creator to bring his or her vision to light. That's often more fun than just watching the latest effort of Miller's or Simonson's sail through.

After that, with lesser creators (even if still very good, or strong in some areas) it gets more challenging.

The Editor in Chief oversees the editors. Among other things, he or she sets the aforementioned "creative goals," or represents the company's position regarding same.

Apropos of my "collegial involvement" scenario, somewhere around here I have a copy of The Wasteland: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound , which shows T.S. Eliot's manuscript, Pound's edits and the final poem as published. It's fascinating, seeing what Eliot wrote, Pound's notes and the accord they reached. Some things Eliot changed, per Pound's advice, some problems he solved in a novel way, not the way Pound advised, and some things were left unchanged. Wow. I recommend the book, though it's expensive.

, which shows T.S. Eliot's manuscript, Pound's edits and the final poem as published. It's fascinating, seeing what Eliot wrote, Pound's notes and the accord they reached. Some things Eliot changed, per Pound's advice, some problems he solved in a novel way, not the way Pound advised, and some things were left unchanged. Wow. I recommend the book, though it's expensive.

Anyway, I had trouble grasping the concept of writer/editors. But, at that point in what I laughingly call a career, mine not to reason why.

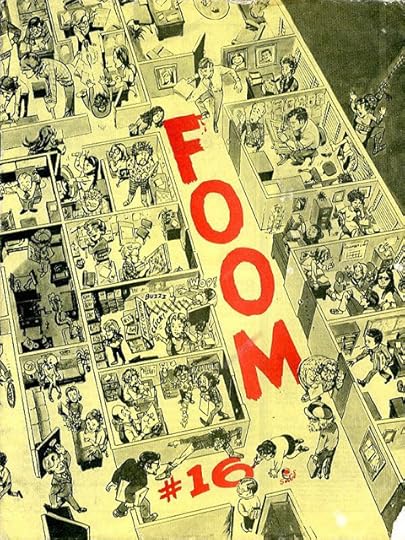

Roy Thomas was the first Marvel writer/editor, unless you count Stan, who was so by virtue of being more-or-less on his own. Len Wein was next. Then, three months or so after I started, when he left staff to write full time, Marv Wolfman. Three weeks or so later, Marv's replacement as Editor in Chief, Gerry Conway, left staff and also became a writer/editor. Nineteen months later, when Archie quit, he, too, became a writer/editor.

So, it seemed to be that once one was EIC, even for a few weeks, one was qualified to become a writer/editor. The theory, I believe, was that no one at Marvel except maybe Stan himself could possibly be capable of editing someone so wonderful as to have achieved the lofty position of EIC. Not even the current EIC.

To some extent, that was sound logic.

Looking around Marvel, I could appreciate why someone like Roy would have serious doubts about having what I considered the normal writer to editor relationship with any of the extant editorial staff members, all "assistant editors" except for me, by the way. No offense to the assistant editors, they were all very smart people, but qualified to work with someone as accomplished, talented and skilled as Roy in the manner described a few 'graphs ago? Not by my reckoning. Not trained, not experienced, not ready for sure.

As for the current EIC, there was pretty much a revolving door on that office at the time, so who knew whom you might be dealing with?

Ever have a bad editor?

It is the Tenth Level of Hell.

To that point, I'd had three editors. As a sidebar to the subsequent parts of this series, I will regale you with the ups and downs of dealing with Mort Weisinger (things not yet discussed), Julie Schwartz and Murray Boltinoff. Each came with his own set of nightmares.

And yet, they were only seventh or eighth level at worst. I could imagine the darker depths of Hell, though.

A bad editor misunderstands your intent. Misses mistakes that might have been corrected. Inserts additional mistakes, thinking, wrongly, that he or she is correcting or improving something. Lines the book up wrong, putting pages out of order. Is oblivious to bad or inappropriate art and lame storytelling. Allows or even encourages terrible coloring. Ruins the work you poured your heart into. And no one ever suspects they're to blame. The readers think you "can't write."

In later years, I suffered such Tenth Level butchers, I mean editors. Roy and the others were right to be afraid.

Anyway….