Gerber and the Duck – Part 2

Say the Secret Word

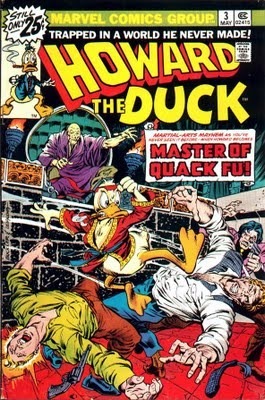

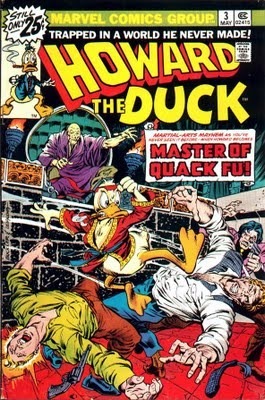

The secret word is cacoethes. One of the first Steve Gerber scripts I remember editing was Howard the Duck #3, the "Master of Quack-Fu" issue. This would have been in early 1976 when I was brand-new associate editor. The plot for that issue had been done before I started at Marvel. The first I saw of the book was at the penciled and scripted (dialogued) stage.

The plot for that issue had been done before I started at Marvel. The first I saw of the book was at the penciled and scripted (dialogued) stage.

One more time, in case there's anyone out there still unfamiliar with creating comics "Marvel style": The writer writes a plot, the penciler draws the story, then the writer writes dialogue and captions to go with the pictures and indicates where the copy should be placed within the panels. Then the book is lettered, inked and colored. Theoretically, the editor, me in the case of HTD #3, sees and checks the book at every stage.

Reading a comic book at the pencil and script stage as the editor is a far different experience than reading the printed book. If you do the job right, you read the plot first to get the overall picture. You have to know where the story is supposed to be going to evaluate the copy that's supposed to be getting it there. Then, you are forced to read the script slowly. Consider it carefully. Balloon by balloon. Pausing a second between units of copy to check to see if the corresponding numbered, blue-pencil placement indication on the board (or photocopy of same) is properly located and spacious enough to accommodate the words. Checking to see that the copy matches what was drawn—can't have a person with a calm, smiling face screaming "AAARRRGH!" Checking everything.

What you're doing, if you're doing it right, is reverse-engineering the writer's process. This copy was written to accompany this image as a step toward this destination. What was the writer thinking?

Too often, the "what was the writer thinking" moment was more like, "What the $#%&#@ was he or she thinking?!"

With HTD #3, and with pretty much every Gerber script that ever crossed my desk, when I realized what must have gone on in his head panel by panel I said, "Wow."

Not far into the script for HTD #3, I put my blue pencil down. His copy was clean and compact. Not a wasted word. If a word wasn't absolutely necessary to the point being achieved, then it was there for the rhythm of the line, or to give a more natural feel. Nothing purposeless, ever. And, joy of joys, he could spell!

Gerber was one of the most gifted wordsmiths I ever encountered. He was also among the most talented creators. Best storytellers. Best dramatists. Most thoughtful and insightful analysts of the human condition, though he tended to be a little dark and cynical.

Which brings us to the secret word: cacoethes. It means an uncontrollable urge or desire. It may suggest a desire for something harmful. My dictionary offers the example "a cacoethes for smoking."

Steve smoked, as I recall. Hmm.

But the cacoethes I'm talking about is of the "incurable passion for writing" kind, per Roman poet, author of the Satires, Juvenal.

Steve apparently had stuff to say that he just had to get out.

Then, he had more stuff to say, and had to get that out.

Cacoethes. A "chronic, overwhelming desire." Also, "a mania."

Steve often did his writing at the Andrews Coffee Shop around the corner from the office. He'd sit there for hours drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. You could smoke pretty much anywhere in those days.

Guess he just had to get out of the apartment. Sometimes a change of venue helps me, too. Sometimes the isolation one finds in a public place is better than the same four walls of your apartment or office screaming at you. It's especially good if someone is bringing you coffee.

Steve was always late. Often badly late. Disastrously late. Cacoethes or not, it must have been hard giving birth to all that stuff sometimes. Painful and difficult, I'm guessing.

More than once, Steve showed up at the office with the revised, pushed back, extended, no, this-time-we-really-mean-it deadline looming, found an empty desk in the editorial room (sometimes Roger Stern would volunteer his) and type as fast as the keys would rebound. Then he'd hand me the final pages of whatever and I'd read the stuff right away, because John Verpoorten would kill me if I didn't.

Clean copy. Compact. Perfectly composed. All spelled correctly.

While writing this little piece, I can't tell you how many times I've gone back to re-compose, retrofit a thought or correct a glitch. I have a sort of double-letter dyslexia that makes me type "Veerporten" when I mean Verpoorten and "isuue" when I mean issue. And, I will occasionally make other spelling misteaks, which must be ferreted out. And I type slowly with two fingers!

In several pages of copy, Steve might have a spell-o or two overstruck with X's and corrected on the fly, but that's about it. (Old-fashioned typers back then. No computers.)

Some may wonder, if Steve was capable of churning out pages of perfect copy in a few cigarettes worth of time, why he was ever late. I think I know. When the fear of not delivering eclipses the fear of committing words to paper, things flow.

Can't trick yourself. Can't fake the fear. Cacoethes notwithstanding, sometimes you have to be ready to burn at the Man-Thing's touch before you can purge what's been growing in your gut.

I rarely had any problems or suggestions regarding Steve's scripts. Once in a while, I'd improve a balloon placement, moving the copy off of a character's body into a less obtrusive space. Once in a long time, I'd see some opportunity to tweak a line. Inevitably, Steve would explain to me precisely what he had been thinking when he wrote the line, his solid rationale for doing it the way he did—and then say, but your suggestion is better. Let's go with that.

Whether it was really better or merely did no harm and he was just humoring me, I don't know. But, whatever. We never had any conflict over the scripts.

Except for one. More on that in a minute.

The one time I know I contributed something useful was in HTD #3. Toward the end, there was a panel that was the key, punch-line moment for the whole story. Steve slipped. He misstated the point.

It was one of those things where you start a scene one work-session, get tired, sleep, and finish it when you wake up without re-reading what you wrote last time. This results in things like Stan's famous Captain America gaff: a line at the end of one page, the words more or less, "Only one of us is going to leave this place alive…" and the next page starting "…and it won't be me!"

The first script I ever edited at Marvel, in 1969, was a Stan Lee Millie the Model story that was a long, shaggy-dog build-up to a punch line about the moon. Stan blew it, making the punch line a non sequitur about Mars. I showed him the mistake. He was very grateful for the catch.

Just as Steve was. He thanked me profusely.

If I had a copy of the book, I could show you the panel and explain the glitch, but I can't do it from memory.

Moving right along….

For all his ranting about the freedom to do graphic violence and other X-rated stuff as described yesterday, Steve never, to my knowledge, attempted to do anything beyond the Marvel specs in Marvel publications. He argued his philosophy but respected the conditions of his employment.

Someone suggested that I was implying previously that Steve wanted to do gratuitous sex and violence. No. He was talking about legitimate, story-essential, harder-edged stuff. He was an excellent writer. I doubt that he ever did anything gratuitous.

The one time we had a serious conflict was over the first Howard the Duck story Steve wrote after the lawsuit was settled. I'll talk about the lawsuit tomorrow, by the way. But anyway, he wrote a story that excised all non-Gerber Duck stories from Duck-canon. I had no problem with that. I objected, however, to the way he did it, which I felt was denigrating and insulting to the writers of those stories.

Gerber wouldn't change it. I did. He found my rewrite unacceptable. So, the issue never saw print.

It has been often said, and it still says on Wikipedia that I objected to the rest of the story, beyond the opening that dealt harshly with those who dared to write the Duck in Gerber's absence, which parodied Secret Wars. Nope. I found that part wickedly funny. I didn't touch it.

It was brilliant parody. It was reminiscent of early issues of HTD, which humorously savaged works by McGregor, Moench and others. Fowl play, you betcha—hysterical and right on.

And fitting, perfect revenge for Secret Wars II #1.

If you think I did the wrong thing regarding Steve's treatment of the other Duck writers, ask them how they felt about it. Ask their friends how they felt. How would you feel?

It was a big enough deal, there was enough sensitivity, and Gerber had proven he was litigious, so I went to both Publisher Mike Hobson and President Jim Galton with my objections to the story. They absolutely supported my position, and Marvel stuck by it.

NEXT: Suits and Lawsuits

The secret word is cacoethes. One of the first Steve Gerber scripts I remember editing was Howard the Duck #3, the "Master of Quack-Fu" issue. This would have been in early 1976 when I was brand-new associate editor.

The plot for that issue had been done before I started at Marvel. The first I saw of the book was at the penciled and scripted (dialogued) stage.

The plot for that issue had been done before I started at Marvel. The first I saw of the book was at the penciled and scripted (dialogued) stage. One more time, in case there's anyone out there still unfamiliar with creating comics "Marvel style": The writer writes a plot, the penciler draws the story, then the writer writes dialogue and captions to go with the pictures and indicates where the copy should be placed within the panels. Then the book is lettered, inked and colored. Theoretically, the editor, me in the case of HTD #3, sees and checks the book at every stage.

Reading a comic book at the pencil and script stage as the editor is a far different experience than reading the printed book. If you do the job right, you read the plot first to get the overall picture. You have to know where the story is supposed to be going to evaluate the copy that's supposed to be getting it there. Then, you are forced to read the script slowly. Consider it carefully. Balloon by balloon. Pausing a second between units of copy to check to see if the corresponding numbered, blue-pencil placement indication on the board (or photocopy of same) is properly located and spacious enough to accommodate the words. Checking to see that the copy matches what was drawn—can't have a person with a calm, smiling face screaming "AAARRRGH!" Checking everything.

What you're doing, if you're doing it right, is reverse-engineering the writer's process. This copy was written to accompany this image as a step toward this destination. What was the writer thinking?

Too often, the "what was the writer thinking" moment was more like, "What the $#%&#@ was he or she thinking?!"

With HTD #3, and with pretty much every Gerber script that ever crossed my desk, when I realized what must have gone on in his head panel by panel I said, "Wow."

Not far into the script for HTD #3, I put my blue pencil down. His copy was clean and compact. Not a wasted word. If a word wasn't absolutely necessary to the point being achieved, then it was there for the rhythm of the line, or to give a more natural feel. Nothing purposeless, ever. And, joy of joys, he could spell!

Gerber was one of the most gifted wordsmiths I ever encountered. He was also among the most talented creators. Best storytellers. Best dramatists. Most thoughtful and insightful analysts of the human condition, though he tended to be a little dark and cynical.

Which brings us to the secret word: cacoethes. It means an uncontrollable urge or desire. It may suggest a desire for something harmful. My dictionary offers the example "a cacoethes for smoking."

Steve smoked, as I recall. Hmm.

But the cacoethes I'm talking about is of the "incurable passion for writing" kind, per Roman poet, author of the Satires, Juvenal.

Steve apparently had stuff to say that he just had to get out.

Then, he had more stuff to say, and had to get that out.

Cacoethes. A "chronic, overwhelming desire." Also, "a mania."

Steve often did his writing at the Andrews Coffee Shop around the corner from the office. He'd sit there for hours drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. You could smoke pretty much anywhere in those days.

Guess he just had to get out of the apartment. Sometimes a change of venue helps me, too. Sometimes the isolation one finds in a public place is better than the same four walls of your apartment or office screaming at you. It's especially good if someone is bringing you coffee.

Steve was always late. Often badly late. Disastrously late. Cacoethes or not, it must have been hard giving birth to all that stuff sometimes. Painful and difficult, I'm guessing.

More than once, Steve showed up at the office with the revised, pushed back, extended, no, this-time-we-really-mean-it deadline looming, found an empty desk in the editorial room (sometimes Roger Stern would volunteer his) and type as fast as the keys would rebound. Then he'd hand me the final pages of whatever and I'd read the stuff right away, because John Verpoorten would kill me if I didn't.

Clean copy. Compact. Perfectly composed. All spelled correctly.

While writing this little piece, I can't tell you how many times I've gone back to re-compose, retrofit a thought or correct a glitch. I have a sort of double-letter dyslexia that makes me type "Veerporten" when I mean Verpoorten and "isuue" when I mean issue. And, I will occasionally make other spelling misteaks, which must be ferreted out. And I type slowly with two fingers!

In several pages of copy, Steve might have a spell-o or two overstruck with X's and corrected on the fly, but that's about it. (Old-fashioned typers back then. No computers.)

Some may wonder, if Steve was capable of churning out pages of perfect copy in a few cigarettes worth of time, why he was ever late. I think I know. When the fear of not delivering eclipses the fear of committing words to paper, things flow.

Can't trick yourself. Can't fake the fear. Cacoethes notwithstanding, sometimes you have to be ready to burn at the Man-Thing's touch before you can purge what's been growing in your gut.

I rarely had any problems or suggestions regarding Steve's scripts. Once in a while, I'd improve a balloon placement, moving the copy off of a character's body into a less obtrusive space. Once in a long time, I'd see some opportunity to tweak a line. Inevitably, Steve would explain to me precisely what he had been thinking when he wrote the line, his solid rationale for doing it the way he did—and then say, but your suggestion is better. Let's go with that.

Whether it was really better or merely did no harm and he was just humoring me, I don't know. But, whatever. We never had any conflict over the scripts.

Except for one. More on that in a minute.

The one time I know I contributed something useful was in HTD #3. Toward the end, there was a panel that was the key, punch-line moment for the whole story. Steve slipped. He misstated the point.

It was one of those things where you start a scene one work-session, get tired, sleep, and finish it when you wake up without re-reading what you wrote last time. This results in things like Stan's famous Captain America gaff: a line at the end of one page, the words more or less, "Only one of us is going to leave this place alive…" and the next page starting "…and it won't be me!"

The first script I ever edited at Marvel, in 1969, was a Stan Lee Millie the Model story that was a long, shaggy-dog build-up to a punch line about the moon. Stan blew it, making the punch line a non sequitur about Mars. I showed him the mistake. He was very grateful for the catch.

Just as Steve was. He thanked me profusely.

If I had a copy of the book, I could show you the panel and explain the glitch, but I can't do it from memory.

Moving right along….

For all his ranting about the freedom to do graphic violence and other X-rated stuff as described yesterday, Steve never, to my knowledge, attempted to do anything beyond the Marvel specs in Marvel publications. He argued his philosophy but respected the conditions of his employment.

Someone suggested that I was implying previously that Steve wanted to do gratuitous sex and violence. No. He was talking about legitimate, story-essential, harder-edged stuff. He was an excellent writer. I doubt that he ever did anything gratuitous.

The one time we had a serious conflict was over the first Howard the Duck story Steve wrote after the lawsuit was settled. I'll talk about the lawsuit tomorrow, by the way. But anyway, he wrote a story that excised all non-Gerber Duck stories from Duck-canon. I had no problem with that. I objected, however, to the way he did it, which I felt was denigrating and insulting to the writers of those stories.

Gerber wouldn't change it. I did. He found my rewrite unacceptable. So, the issue never saw print.

It has been often said, and it still says on Wikipedia that I objected to the rest of the story, beyond the opening that dealt harshly with those who dared to write the Duck in Gerber's absence, which parodied Secret Wars. Nope. I found that part wickedly funny. I didn't touch it.

It was brilliant parody. It was reminiscent of early issues of HTD, which humorously savaged works by McGregor, Moench and others. Fowl play, you betcha—hysterical and right on.

And fitting, perfect revenge for Secret Wars II #1.

If you think I did the wrong thing regarding Steve's treatment of the other Duck writers, ask them how they felt about it. Ask their friends how they felt. How would you feel?

It was a big enough deal, there was enough sensitivity, and Gerber had proven he was litigious, so I went to both Publisher Mike Hobson and President Jim Galton with my objections to the story. They absolutely supported my position, and Marvel stuck by it.

NEXT: Suits and Lawsuits

Published on August 02, 2011 11:01

No comments have been added yet.

Jim Shooter's Blog

- Jim Shooter's profile

- 85 followers

Jim Shooter isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.