Writer/Editors – Part 1

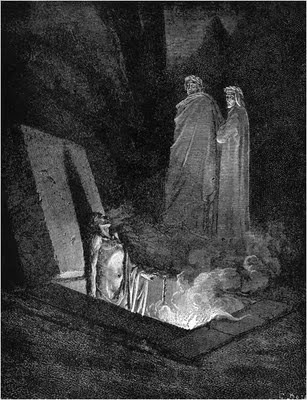

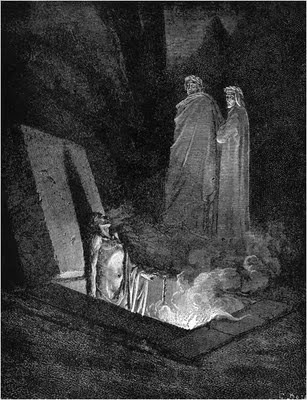

The Tenth Level of Hell

The first time I ever heard the term "writer/editor" was shortly after arriving for my first day as associate editor of Marvel Comics on the first working day of January, 1976. At first I thought it must mean a part-time writer who also served as an editor for other writers.

The first time I ever heard the term "writer/editor" was shortly after arriving for my first day as associate editor of Marvel Comics on the first working day of January, 1976. At first I thought it must mean a part-time writer who also served as an editor for other writers.

Nope. It meant someone who was the editor of his own work.

What?

That just baffled me. The point of having an editor is having an objective reviewer. All right, it's way more than that. Of course. An editor is supposed to be a skilled, knowledgeable, interested party whose involvement with the work is not as direct and personal as the writer's (and, in the case of comics, other creative contributors), and therefore can evaluate the work with some detachment.

Furthermore….

The job of a comics editor, as I was taught, is part business, part creative. An editor manages the business directly related to producing the comics: keeping things on schedule and being the first-line overseer of direct expenditures; governing the process of bringing together the art and editorial components and the assembly of same into a ready-to-print package. With regard to the latter, he or she is the "client" of both the art production department, which carries out the physical parts of the preparation of the package, and the manufacturing or print-production department, which produces and delivers to distributors the actual product.

Plus, an editor oversees the creative work and sees to it that the creative goals are achieved. This may include working with the writer to develop the story and contributing creatively, working with the artists to make sure the story is being told effectively, overseeing the creation of the cover and all non-comics editorial, such as letter columns, editorials, additional features, whatever.

So, the editor is something like a film producer/film director, responsible in a project management sense as well as creatively. By director, I don't mean that the editor should be the "auteur," though that has happened in comics sometimes. Usually, the editor provides some creative guidance, support and backstopping. He or she is the publisher's face to the creators.

The ideal situation is when the creators involved on a project don't need any guidance, support or backstopping. They're that good and that on the mark. Then, the editor can just watch and applaud—except for the nuts-and-bolts making it print-ready part. That never goes away.

Near ideal is when the creator enjoys or needs some collegial involvement and the editor gets to chime in a little, helping the creator to bring his or her vision to light. That's often more fun than just watching the latest effort of Miller's or Simonson's sail through.

After that, with lesser creators (even if still very good, or strong in some areas) it gets more challenging.

The Editor in Chief oversees the editors. Among other things, he or she sets the aforementioned "creative goals," or represents the company's position regarding same.

Apropos of my "collegial involvement" scenario, somewhere around here I have a copy of The Wasteland: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound , which shows T.S. Eliot's manuscript, Pound's edits and the final poem as published. It's fascinating, seeing what Eliot wrote, Pound's notes and the accord they reached. Some things Eliot changed, per Pound's advice, some problems he solved in a novel way, not the way Pound advised, and some things were left unchanged. Wow. I recommend the book, though it's expensive.

, which shows T.S. Eliot's manuscript, Pound's edits and the final poem as published. It's fascinating, seeing what Eliot wrote, Pound's notes and the accord they reached. Some things Eliot changed, per Pound's advice, some problems he solved in a novel way, not the way Pound advised, and some things were left unchanged. Wow. I recommend the book, though it's expensive.

Anyway, I had trouble grasping the concept of writer/editors. But, at that point in what I laughingly call a career, mine not to reason why.

Roy Thomas was the first Marvel writer/editor, unless you count Stan, who was so by virtue of being more-or-less on his own. Len Wein was next. Then, three months or so after I started, when he left staff to write full time, Marv Wolfman. Three weeks or so later, Marv's replacement as Editor in Chief, Gerry Conway, left staff and also became a writer/editor. Nineteen months later, when Archie quit, he, too, became a writer/editor.

So, it seemed to be that once one was EIC, even for a few weeks, one was qualified to become a writer/editor. The theory, I believe, was that no one at Marvel except maybe Stan himself could possibly be capable of editing someone so wonderful as to have achieved the lofty position of EIC. Not even the current EIC.

To some extent, that was sound logic.

Looking around Marvel, I could appreciate why someone like Roy would have serious doubts about having what I considered the normal writer to editor relationship with any of the extant editorial staff members, all "assistant editors" except for me, by the way. No offense to the assistant editors, they were all very smart people, but qualified to work with someone as accomplished, talented and skilled as Roy in the manner described a few 'graphs ago? Not by my reckoning. Not trained, not experienced, not ready for sure.

As for the current EIC, there was pretty much a revolving door on that office at the time, so who knew whom you might be dealing with?

Ever have a bad editor?

It is the Tenth Level of Hell.

To that point, I'd had three editors. As a sidebar to the subsequent parts of this series, I will regale you with the ups and downs of dealing with Mort Weisinger (things not yet discussed), Julie Schwartz and Murray Boltinoff. Each came with his own set of nightmares.

And yet, they were only seventh or eighth level at worst. I could imagine the darker depths of Hell, though.

A bad editor misunderstands your intent. Misses mistakes that might have been corrected. Inserts additional mistakes, thinking, wrongly, that he or she is correcting or improving something. Lines the book up wrong, putting pages out of order. Is oblivious to bad or inappropriate art and lame storytelling. Allows or even encourages terrible coloring. Ruins the work you poured your heart into. And no one ever suspects they're to blame. The readers think you "can't write."

In later years, I suffered such Tenth Level butchers, I mean editors. Roy and the others were right to be afraid.

Anyway….

Though Roy's books weren't given to me to edit in earlier stages because of Roy's writer/editor status, they did come to the editorial room to be proofread before going to the printer. Because I was officer of the deck, when possible, I proofread Roy's books myself. Why? Because I thought that if editorial had only one crack at them, I ought to be the one to take it. Also, rightly or wrongly, I felt that I would do the best job, and had the best chance of catching mistakes. Also, because Roy was, probably still is, a major fussbudget and detail tweezer, and if there was going to be any heat for a screw-up on our end, I figured that I should be the one to take it.

Aside from the occasional letterer's mistake or small art glitch, Roy's books were almost always pristine. Only a few times did I ever call Roy to ask him about something or make a suggestion. Roy was always friendly and reasonable. I think. He talked so fast I always ended up three or four sentences behind, comprehension wise.

(ASIDE: Once Howard Chaykin came into the editorial room, sat down at an empty desk and called Roy to discuss something. We all heard Howard's side of the conversation, which went something like this:

"Hello, R….

"Okay….

"But…."

In seconds, Roy apparently signed off and hung up. Howard said to all in earshot, "Why did Roy just read me War and Peace?")

Anyway, no problems back in the early days between and Roy and I that I remember.

Sticking with the Roy example for now—we'll get to the others tomorrow—yes, I understood the concerns he might have ceding any responsibility, much less authority to people unknown, or of dubious qualifications.

And his work was generally outstanding.

So what was the problem?

NEXT: The Problem

The first time I ever heard the term "writer/editor" was shortly after arriving for my first day as associate editor of Marvel Comics on the first working day of January, 1976. At first I thought it must mean a part-time writer who also served as an editor for other writers.

The first time I ever heard the term "writer/editor" was shortly after arriving for my first day as associate editor of Marvel Comics on the first working day of January, 1976. At first I thought it must mean a part-time writer who also served as an editor for other writers. Nope. It meant someone who was the editor of his own work.

What?

That just baffled me. The point of having an editor is having an objective reviewer. All right, it's way more than that. Of course. An editor is supposed to be a skilled, knowledgeable, interested party whose involvement with the work is not as direct and personal as the writer's (and, in the case of comics, other creative contributors), and therefore can evaluate the work with some detachment.

Furthermore….

The job of a comics editor, as I was taught, is part business, part creative. An editor manages the business directly related to producing the comics: keeping things on schedule and being the first-line overseer of direct expenditures; governing the process of bringing together the art and editorial components and the assembly of same into a ready-to-print package. With regard to the latter, he or she is the "client" of both the art production department, which carries out the physical parts of the preparation of the package, and the manufacturing or print-production department, which produces and delivers to distributors the actual product.

Plus, an editor oversees the creative work and sees to it that the creative goals are achieved. This may include working with the writer to develop the story and contributing creatively, working with the artists to make sure the story is being told effectively, overseeing the creation of the cover and all non-comics editorial, such as letter columns, editorials, additional features, whatever.

So, the editor is something like a film producer/film director, responsible in a project management sense as well as creatively. By director, I don't mean that the editor should be the "auteur," though that has happened in comics sometimes. Usually, the editor provides some creative guidance, support and backstopping. He or she is the publisher's face to the creators.

The ideal situation is when the creators involved on a project don't need any guidance, support or backstopping. They're that good and that on the mark. Then, the editor can just watch and applaud—except for the nuts-and-bolts making it print-ready part. That never goes away.

Near ideal is when the creator enjoys or needs some collegial involvement and the editor gets to chime in a little, helping the creator to bring his or her vision to light. That's often more fun than just watching the latest effort of Miller's or Simonson's sail through.

After that, with lesser creators (even if still very good, or strong in some areas) it gets more challenging.

The Editor in Chief oversees the editors. Among other things, he or she sets the aforementioned "creative goals," or represents the company's position regarding same.

Apropos of my "collegial involvement" scenario, somewhere around here I have a copy of The Wasteland: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound

, which shows T.S. Eliot's manuscript, Pound's edits and the final poem as published. It's fascinating, seeing what Eliot wrote, Pound's notes and the accord they reached. Some things Eliot changed, per Pound's advice, some problems he solved in a novel way, not the way Pound advised, and some things were left unchanged. Wow. I recommend the book, though it's expensive.

, which shows T.S. Eliot's manuscript, Pound's edits and the final poem as published. It's fascinating, seeing what Eliot wrote, Pound's notes and the accord they reached. Some things Eliot changed, per Pound's advice, some problems he solved in a novel way, not the way Pound advised, and some things were left unchanged. Wow. I recommend the book, though it's expensive. Anyway, I had trouble grasping the concept of writer/editors. But, at that point in what I laughingly call a career, mine not to reason why.

Roy Thomas was the first Marvel writer/editor, unless you count Stan, who was so by virtue of being more-or-less on his own. Len Wein was next. Then, three months or so after I started, when he left staff to write full time, Marv Wolfman. Three weeks or so later, Marv's replacement as Editor in Chief, Gerry Conway, left staff and also became a writer/editor. Nineteen months later, when Archie quit, he, too, became a writer/editor.

So, it seemed to be that once one was EIC, even for a few weeks, one was qualified to become a writer/editor. The theory, I believe, was that no one at Marvel except maybe Stan himself could possibly be capable of editing someone so wonderful as to have achieved the lofty position of EIC. Not even the current EIC.

To some extent, that was sound logic.

Looking around Marvel, I could appreciate why someone like Roy would have serious doubts about having what I considered the normal writer to editor relationship with any of the extant editorial staff members, all "assistant editors" except for me, by the way. No offense to the assistant editors, they were all very smart people, but qualified to work with someone as accomplished, talented and skilled as Roy in the manner described a few 'graphs ago? Not by my reckoning. Not trained, not experienced, not ready for sure.

As for the current EIC, there was pretty much a revolving door on that office at the time, so who knew whom you might be dealing with?

Ever have a bad editor?

It is the Tenth Level of Hell.

To that point, I'd had three editors. As a sidebar to the subsequent parts of this series, I will regale you with the ups and downs of dealing with Mort Weisinger (things not yet discussed), Julie Schwartz and Murray Boltinoff. Each came with his own set of nightmares.

And yet, they were only seventh or eighth level at worst. I could imagine the darker depths of Hell, though.

A bad editor misunderstands your intent. Misses mistakes that might have been corrected. Inserts additional mistakes, thinking, wrongly, that he or she is correcting or improving something. Lines the book up wrong, putting pages out of order. Is oblivious to bad or inappropriate art and lame storytelling. Allows or even encourages terrible coloring. Ruins the work you poured your heart into. And no one ever suspects they're to blame. The readers think you "can't write."

In later years, I suffered such Tenth Level butchers, I mean editors. Roy and the others were right to be afraid.

Anyway….

Though Roy's books weren't given to me to edit in earlier stages because of Roy's writer/editor status, they did come to the editorial room to be proofread before going to the printer. Because I was officer of the deck, when possible, I proofread Roy's books myself. Why? Because I thought that if editorial had only one crack at them, I ought to be the one to take it. Also, rightly or wrongly, I felt that I would do the best job, and had the best chance of catching mistakes. Also, because Roy was, probably still is, a major fussbudget and detail tweezer, and if there was going to be any heat for a screw-up on our end, I figured that I should be the one to take it.

Aside from the occasional letterer's mistake or small art glitch, Roy's books were almost always pristine. Only a few times did I ever call Roy to ask him about something or make a suggestion. Roy was always friendly and reasonable. I think. He talked so fast I always ended up three or four sentences behind, comprehension wise.

(ASIDE: Once Howard Chaykin came into the editorial room, sat down at an empty desk and called Roy to discuss something. We all heard Howard's side of the conversation, which went something like this:

"Hello, R….

"Okay….

"But…."

In seconds, Roy apparently signed off and hung up. Howard said to all in earshot, "Why did Roy just read me War and Peace?")

Anyway, no problems back in the early days between and Roy and I that I remember.

Sticking with the Roy example for now—we'll get to the others tomorrow—yes, I understood the concerns he might have ceding any responsibility, much less authority to people unknown, or of dubious qualifications.

And his work was generally outstanding.

So what was the problem?

NEXT: The Problem

Published on August 08, 2011 11:40

No comments have been added yet.

Jim Shooter's Blog

- Jim Shooter's profile

- 85 followers

Jim Shooter isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.