R. Mark Liebenow's Blog: Nature, Grief, and Laughter, page 9

December 13, 2015

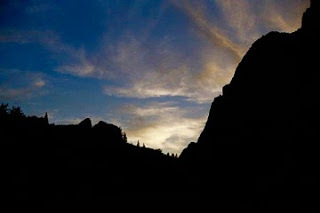

The Transcendence of Nature

Its wonder, majesty, and downright gob-smacking awe.

Nature has the power to lift us out of ourselves, especially when we’re in the wilderness.

It renews, restores, and rehabilitates us when the pressure and drudgery of city life become too much. If you have a place in nature where you go because you feel alive there, then you’ll appreciate the following quotes. While these writers were all speaking about Yosemite, and often in terms of spirituality, feel free to translate the words to fit your own favorite place, whether it’s at the ocean, in the desert, or out on the prairie.

*

"That mute appeal (pointing to El Capitan) illustrates it, with more convincing eloquence than can the most powerful arguments of surpliced priests." -- Lafayette Bunnell, 1851

"...as the scene opened in full view before us, we were almost speechless with wondering admiration at its wild and sublime grandeur.” --James Hutchings, 1855

A "passage of scripture [is] written on every cliff." -- Thomas Starr King, Rev. 1860

"I am sitting here in a little shanty made of sugar pine shingles this Sabbath evening.” ‘Here I worship as never before.’ -- John Muir, 1868

"I remembered the famous Zen saying, 'When you get to the top of a mountain, keep climbing.' Upon reaching the top Ryder [Snyder] gives out a 'beautiful broken yodel of a strange musical and mystical intensity' and then suddenly everything was just like jazz." -- Jack Kerouac, Dharma Bums

"The experience from which these Yosemite poems come is the experience of interacting with the Other — of constantly trying to be aware of the Universe as all one body, of trying not to be separate from it but recognize every part of it as part of yourself. There is nothing alien in it at all. Sometimes interacting with the Other remains theoretical. Even then it is interesting. Sometimes it is an experience. When it is, I can make a poem out of it. It takes on the force of poetry." -- Gary Snyder, 1955

Published on December 13, 2015 14:02

December 6, 2015

Cantus

In listening to Arvo Part’s Cantus in Memorium, I am struck by the silence.

In listening to Arvo Part’s Cantus in Memorium, I am struck by the silence.Silence is programmed into the score as part of the music. This silence was not absence, of waiting for musicians to play the next notes. It was presence. It was not waiting for something to happen. It was already happening, because we were waiting in the concert hall, and listening.

When we go into nature, we travel with the thousands of thoughts that crowd our head. We enter with the noises of the city ringing in our ears. We have learned to tune out much of what we hear going on around us in our concrete environment.

Bells have a presence in the Part’s composition. Part was a member of the Russian Orthodox Church where bells have a rich history of ringing over the mountains and calling people to come to something important, an awareness or a gathering.

In Cantus, at the end when the strings descend through dissonance to resonate together, the last bell rings, and it feels like the sky suddenly clears, and releases the tension after the turbulence of a storm.

We feel our hearts open, and rise.

Published on December 06, 2015 06:37

November 29, 2015

A Place Apart: Nature

Late in the fall one year, I hiked up steep switchbacks for two hours from the valley floor to Glacier Point in Yosemite. The wilderness was surprisingly quiet and still at 8,000 feet.

A forest of sugar pines was behind me. In front was Half Dome and a view that stretched over the gray granite peaks and domes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains

No one else was here. The summer crowds had gone home months before. A few tiny people walked around on the valley floor far below. Except for a few squirrels and one Steller’s jay, no other creatures were letting their presence be known.

The breeze hummed lightly as it twirled the needles on the pines. There was a hush as the wind flowed over the nearby mountains on its way east. Now and then when the breeze shifted, I caught the sounds of Nevada and Vernal Falls.

Sitting on a boulder, this felt like home. I couldn’t stay here, of course. There was no shelter, food, or water, yet I felt connected to something authentic, something real in a primal sense, something eternal.

Was it awe of the landscape that pulled me away from my ordinary preoccupations and made me think of mystery? Was it reverence for a place that was sacred to the Ahwahnechee, as well as to John Muir? Or was it respect for an ancient wilderness that had existed and looked like this for thousands of years?

It was probably all of these. I didn’t really need to know the why. Whatever it is, every time I come here, the burdens of life slide off and I feel centered and renewed.

Standing alone on top of a mountain, longing rose for something deeper than what everyday life has brought. It was longing for honest community, enduring hope, and unfettered joy.

In the wilderness of our hearts, the holidays are rooted.

Published on November 29, 2015 05:58

November 22, 2015

John Muir and the End of the World

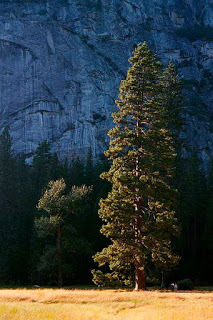

(notice the two people standing at the base of the tree)

John Muir is one of my patron saints. He said, “Creation was not an act, it is a process, and it is going on today as much as it ever was.”

When we go to natural places like Yosemite (or Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons, etc.), it looks like it never changes. Yet if we go often, and pay attention to the details, we notice that everything is a little different than it was the last time we were here.

Mirror Lake has gradually filled in with sediment brought down by the river and becomes a meadow. Flakes of rock the size of houses have broken off the valley walls and fallen, leaving white spots behind on the gray granite. A meadow in the west end of the valley that was completely open now has quite a few trees. The spring flood carved a new path through the valley and shifted the river 500 feet.

Everything is continually changing in nature. Lesson number 1.

The natural world continues to evolve. Lesson number 2.

We are part of the movement of creation, too, as well as part of its destruction. One world ends and a new one begins. Old sections of our cities are town down, and new buildings are constructed.

We want everything we love to stay the same, yet even we aren’t who we used to be. We learn new things and our thinking shifts. We develop relationships, and feel our hearts deepen. We grow. We evolve. We would not want to be who we were ten, twenty, or thirty years ago because we are aware of so much more now. We are wiser and, hopefully, more compassionate.

Yet, when something changes suddenly, like when the slab of rock the size of a football field fell from Glacier Point and knocked down thousands trees at Happy Isles, changing it from a dark shaded grove into an open-air space, I grieved the loss of a unique place that I loved, and was not ready to celebrate the airy beauty of what it had become.

Life and death are ongoing in Yosemite. Lesson number 3.

Young and old deer are killed by coyotes because they’re vulnerable. And while I’ve come to understand this, it’s still hard to accept it, to feel that this is okay.

Muir has long been a companion on the trail for me as I hike through Yosemite, but I found out something new about him after my wife died. Muir, who understood the ways of nature and accepted the cycle of life and death, was so devastated by his wife’s death that he spent a year in the desert Southwest trying to get back on his feet.

Then, when his beloved Hetch Hetchy valley was dammed to provide water for San Francesco, he died of a broken heart. Two of his great loves had been taken away, and to him it felt like the end of his world.

The evolution going on in the natural world doesn’t mean it is getter better. Nature is not more beautiful now because of all its changes over the last thousand years. It was beautiful then, and it’s beautiful now. It’s just different.

We become attached to the beauty that was, and miss the beauty that has replaced it. But sometimes the changes are just too great.

Published on November 22, 2015 06:07

November 15, 2015

Refuge in Nature

Your place of refuge may be different than mine, but it’s necessary to go there when something has twisted your life into knots. It could be grief, loss of a job, a health diagnosis, a relationship coming apart, or a crisis of faith.

Your place of refuge may be different than mine, but it’s necessary to go there when something has twisted your life into knots. It could be grief, loss of a job, a health diagnosis, a relationship coming apart, or a crisis of faith.Wherever you go for renewal, to feel comforted, accepted, and inspired, it’s likely to be a place or an activity that brought you pleasure before trauma struck. Now it becomes therapeutic.

For one person it may be carpentry or gardening, for another it may be working with horses. Maybe it’s going to the movies, the ocean, or the golf course. Whatever it is, this is where you can step back, focus on something else for a time, while at the same time, work your way through the problem in the back alleys of your mind.

When some thought or feeling shows up out of the blue, pause and listen for where it is leading.

My path was in Yosemite, and the following are notes from one of my trips. I hope you find parallels with your own journey.

*Hiking any long trail in the mountains is rugged and demands more endurance than I think I have, but I want the challenge to see if I measure up. I need to be worn out by physical activity because I’ve been sitting at home for too long with grief, and nature comforts me.

This morning a Jeffrey pine stands in front of me. I rub my hand over the bark, feel its roughness, and lean close to see how it smells. I can never remember if it’s the Jeffrey or the Ponderosa that smells like vanilla. Ah, it’s the Jeffrey.

I listen to the Merced River flowing nearby, dip my hand into the cold of its snowmelt water, and feel the power of its surge. I wander into the meadow, sit on the ground, and look closely at its plants, at the hairy-stalked milkweed, the long stemmed grasses, and the glorious purple lupine.

My intention last night was to hike into the mountains today. But what do I feel like doing this morning? Do I really want to tackle a demanding hike, or would I rather sit by the river and read, or maybe saunter aimlessly?

I will try not to think of grief, or use the hours to organize my future. I will focus on nature and exist in this moment as fully as I can and see what happens.

No one here knows who I am or what I’m struggling with, and I can tell them or not. I’m untethered from my past, and free to express whatever thoughts and feelings I have this morning. In the next hour I may uncover deeper feelings and contradict myself. So be it. I will be enigmatic. I will find people I like, and we will share food and drink, and exchange stories that make us laugh and give us courage.

I will listen to nature, to the breezes humming through the branches of the Sugar pines, the opinionated chatter of blue jays, the haunting caws of ravens, and the scuffling of chipmunks through the leaves.

I will lean against a mountain, take in the view, and lose myself in wonder.

When I come across a side trail, I will take it, even if I don’t know where it goes. It will lead me through a new part of the forest, over the mountain, and down into the valley with the shadows of death. The path also leads me through my battered heart.

The path is my way and my refuge. I shall not want.

Published on November 15, 2015 13:06

November 8, 2015

Being in Community

I’m a rugged, individual American. Every American is. (This probably holds true for whatever country you belong to.)

I’m a rugged, individual American. Every American is. (This probably holds true for whatever country you belong to.)Or at least we think we’re expected to be this. And that’s a problem as our cities become larger and we have to drive to the grocery store rather than walk. We don’t sit on our front porches anymore and talk to people walking by because the houses in new housing developments don’t have porches, or sidewalks, or grocery stores.

We’ve lost our sense of belonging to a community of people. When we do gather together, it tends to be for national celebrations like July 4th or for sporting events. The crowd is large and anonymous, and we don’t share on the personal level. We talk to the people we came with, and that’s about it.

Having a community where we know each other is important for our sense of belonging.

When I’m camping, community becomes crucial because things happen outdoors. If I break an ankle on a trail, I will need help getting back. If a cold thunderstorm soaks my sleeping bag and clothes, I will need someone to offer me shelter. When climbers have an accident on a rock wall, the community of climbers rallies around to get them safely off the mountain and taken care of.

We need each other if we are going to survive.

One year as I arrived in Camp Four in Yosemite, the woman who had been staying in the campsite before me gave me her food as she returned to Australia. When I left, I passed my food on to those who were arriving.

When I’m hiking up the trail to the top of Half Dome, community forms with strangers because we’re moving at the same pace for hours. Often we will take rest breaks at the same time on that steep, sandy trail as it heads for an elevation of 9000 feet. We talk and learn about each other’s lives. We suggest other trails that we think the other one would like. When we get to the top, we toast each other’s success as we marvel at the astonishing view of the Sierra Nevada range.

We are told to be strong individuals by society. But it’s in community that we learn the world is greater than ourselves.

It’s in community where our strengths flourish.

Published on November 08, 2015 06:11

November 1, 2015

The Spirit Land

Sometimes we hear the voice of a family member who has died, or we feel their presence. Is it real?

Out of the blue, I think to send something nice to a friend in another state. When it arrives three days later, it’s exactly what she needs. Is something more going on than coincidence?

We are more connected to each other than we think, both the living and the dead.

Soon after I arrive in Yosemite, a coyote always appears, either sitting along the road to welcome me in, or trotting across the meadow with a glance. Molly says Coyote is my spirit guide. She might be right. Some people say they never see coyotes. I see them all the time.

As I hike, I feel the companionship of Nature’s spirit, and let it guide me where it wants. The wind comes near and advises me about tomorrow’s weather. Taking a break, I fall asleep along the river, feeling I have come home.

We are not limited by what we can see.

I sometimes wonder if my ancestors left predispositions in my genes, some trait that kept them alive and guides me like a hidden instinct. Science is increasingly saying this is possible.

When I’m hiking in the backcountry, I find trail ducks. These are short stacks of rocks left by hikers to indicate turns in the trail that are hard to see. They left them as a kindness for people who will come later; people they will never meet.

Black Elk believed that all members of creation were brothers and sisters to each other — the buffalo, mountains, human beings, rivers, horses, coyotes, and ravens. The Sioux pray to the Grandparents in the afterlife to send messages to guide them. And they do.

The Ahwahnechee of Yosemite believed that the deer willingly gave themselves up to their arrows, knowing that the Ahwahnechee had to eat.

Today is All Saints Day on the Christian calendar. Think about and honor those who have been saints in your life, those who were there at crucial times and helped you survive.

Many people hold celebrations this weekend — All Hallows Eve (Halloween), All Saints Day, and All Souls Day. The ancient Celtic people observed Samhain, when the living could talk to the dead. Latin American countries have a similar celebration called Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, with its fixation on skulls. It’s an observance that traces its roots back to the Aztecs, who believed that the deceased preferred to be celebrated, rather than mourned.

When we share something personal with others, this part of us begins to live in them. This does not die when we do, but continues to guide and inspire them, and it sometimes makes them laugh.

I believe that the spiritual can be more real than the physical, and that matters of the spirit are not bound by the laws that govern physical objects.

I believe that everyone I’ve ever loved is still here with me in some way.

This weekend I intend to listen for what I cannot see, matters that change the world, trail ducks of the Spirit — hope, faith, and love.

Published on November 01, 2015 04:11

October 25, 2015

The Seasons Within Me

I used to think that, for the most part, summer progressed smoothly into autumn, and autumn into winter, each day taking the next step on the way. Then I began to pay attention. Each season often has a pause, as though the earth is having second thoughts and is reluctant to let go of what has been.

I used to think that, for the most part, summer progressed smoothly into autumn, and autumn into winter, each day taking the next step on the way. Then I began to pay attention. Each season often has a pause, as though the earth is having second thoughts and is reluctant to let go of what has been.A few days of unseasonably warm weather in autumn is often called Indian Summer, and yet it doesn’t feel like summer or autumn, but something that is all its own.

*

The air hesitates, too, as if nature has hit the pause button. A light jacket is enough to stay warm. The leaves on the trees are filled with colors. The clear blue sky is sharp and deep, and not yet soft with the scatter of snow crystals high up in the atmosphere.

This pause can last a few days or a week. Then the season shifts back into gear and each night is a little colder, and each day the daylight is a little shorter. Then the last of the autumn leaves drop, late blooming flowers release their colors to the air and draw themselves back underground, and the rich warm hues of the meadows turn brown, black, and mauve.

*

I pause, too, and let the rest of me catch up. There are seasons changing within me. As I let go of the endless activity of summer, I open to a quieter season of reflection.

Yet each season calls us to grow, reflect, learn, and change. Creating isn’t limited to summer, nor reflection to winter. Each season pulls out from us another aspect of our personality, and pulls us inside to deal with something else.

Each season we step away from what no longer is and step toward what will be. Each season challenges us to grow.

Each day we are born again new.

Published on October 25, 2015 06:37

October 18, 2015

Thunderstorm in the Mountains

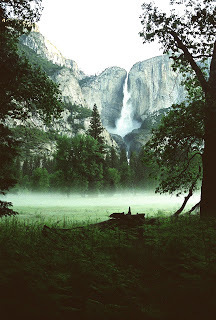

from an October a few years ago *As I come out of Tenaya Canyon in Yosemite after a hike, the skies darken and it begins to sprinkle. Then thunder crackles and bangs through the sky. The wind increases and blows branches and camp chairs across the Upper Pine campground. I love rolling thunder, especially the type that I can feel rumbling deep in my chest. Hurrying back to camp, I grab my rain gear and head for the meadows so that I can see what the storm is doing to the surrounding mountains.

A white cloud is forming just below the lip of Upper Yosemite Fall. It's the only cloud this low. The color of the water in the fall matches the white of the cloud so it looks like the fall is pouring into the cloud like a basin, and it seems that more water is pouring into the cloud than is coming out.

I wonder if the atmospheric conditions are such that the fall is creating the cloud? Maybe the cool air flowing down the Yosemite Creek canyon behind the fall is mixing with the humid, warmer air rising from the valley floor and forming a cloud at the junction. Lightning flashes and unhitches the cloud from the fall to float up the valley.

I walk through the meadows in the middle of the valley in the pouring rain, going from Leidig to Sentinel and down to Stoneman and Ahwahnee. When the rain slows to a drizzle, I return to camp and meet Tim and Dave who arrived today. We discover that as I was watching that cloud develop below Yosemite Falls, they were at the top of the Falls photographing it from above as lightning started zipping around their heads. Later I learn from a ranger that the storm dropped so much snow at Tioga Pass they had to close the road.

I turn in early at 8:30 p.m. to get sleep in case the storm intensifies overnight and I have to battle it to keep my tent upright. I sleep fitfully for ten hours as the rain resumes, waking repeatedly to listen to the sounds of rain on the tent and thunder echoing off the valley walls.

The storm makes it clear that I’m not in control here. The weather, the wild animals, and the exposure to the elemental forces of the earth tell me that I am visiting a world where matters of life and death go on, and nothing is assured except this moment.

Overnight the air gets colder as the freeze in the highlands moves down into the valley. Temperatures have fallen into the 20s. The carrots in my cooler are frozen. It's supposed to warm up a few degrees today and a few more tomorrow, but the sun won't rise over the south rim of the valley and reach Camp 4 until 10 a.m. keeping camp cold.

Today being a rest day between long hikes, I don’t have anything scheduled, so I walk around the valley floor trying to get warm. I may have to break out my insulated winter coat that makes me look like a blue Michelin man.

Last night, to my great delight, I found out that the hood to my new sleeping bag works handles cold weather well. It’s called a "mummy bag” and I can pull the drawstring so that it surrounds my head and keeps it warm. I can draw it so tight that only my nose sticks out. This allows me to breathe fresh air and expel moist breath outside the bag, while I stay warm and dry inside.

If I have a warm place to sleep, I relish tromping around in the cold. If I'm cold and wet and know that this isn't going to change, I don't enjoy being outside. I confess, it's a growing edge, to enjoy nature’s beauty whether I am warm, cold, or wet.

I am not St. Cuthbert who intentionally sat in the cold North Sea off Lindesfarne, England to commune with nature (or deaden his body so he could pray). I pray best with my senses open to the glorious, transcendent beauty of the wilderness.

Published on October 18, 2015 06:58

October 11, 2015

Hiking in the Rain

Today is a day of rest for my body. The physical exertions of yesterday's dawn-to-dusk hike wore me out. Generally the day after any hike longer than 10 hours is a rest day, or a day of a few short hikes, time to let the body recoup and stretch its muscles.

Today is a day of rest for my body. The physical exertions of yesterday's dawn-to-dusk hike wore me out. Generally the day after any hike longer than 10 hours is a rest day, or a day of a few short hikes, time to let the body recoup and stretch its muscles. So far I detect no serious tightness in my legs or hot spots on my feet. Although my mind wants to go on another long hike and see more mountain scenery, today’s sporadic rain dilutes my drive and encourages me to saunter around slowly and observe the details of nature more closely.

This is also a good time to catch up on housekeeping chores in the tent, as I tend to dump things in when I return late from one hike, reset my backpack for the next day’s activity, and take off at daybreak.

The impact of weather on camping and hiking is brought home as I encounter changing weather conditions in mid October. When it's rainy, much of my attention is focused on staying relatively dry. My first concern is for the inside of the tent. If my tent and sleeping bag get wet, the trip is over. Once the tent is secure, then I resign myself to sloshing around all day, with parts of me perpetually wet.

I can endure a day of wet feet and half-wet pants, wet hands and a wet face, as long as I have a dry place to sleep at night. After yesterday's late rain, I had to deal with a little seepage under the tent and moved my tent to a spot under a tree that stayed dry during the storm.

Cold, wet weather is a different creature.

Hiking in the mountains when it's raining isn't fun because the trails are always going up or down and are slippery and potentially dangerous in spots. The added weight and layers of rain gear slow me down, making long hikes cumbersome, and blisters are more likely to form on cold, soggy toes. Hiking over flat ground in the rain is fine because not much friction is put on the bottom of my feet.

And yet, the mountains in the rain are endless scenes of wonder. The glistening tree leaves. The hovering of clouds over the peaks of the mountains, hiding them from view. The rising of mist from the forests that drift low over the meadows.

The sounds of the natural world also come alive, from the soft plick of raindrops dropping off the branches of a ponderosa pine onto the layer of needles, to the sharp schiss of rivulets of water racing down the valley wall, to the growing roar of the river as it fills and surges with water.

It’s tempting to scamper up to scenic vistas in the mountains to see the panoramas, knowing that I’ll have to slide most of the way back down.

Why does walking through the rain in a wilderness place move deeper emotions? What is it about fog that seems to erase the boundaries of time?

Published on October 11, 2015 05:36