R. Mark Liebenow's Blog: Nature, Grief, and Laughter, page 2

September 21, 2025

Talking to the Trees

When a friend received bad news about her cancer, I thought, “I’ll talk to the trees.”

Bear with me for a moment. I used to light candles, think of those who needed support, and prayed. I often still do, but talking to the trees seemed to be the right thing to do here.

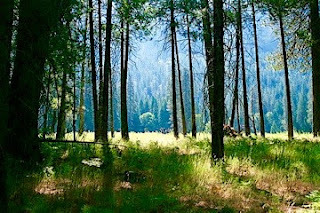

I went out and spoke to the trees in the forest behind my house. I talked to their branches, their leaves, and finally to their roots, because I wasn’t sure where their communication receptors were. Deeper in the woods, I found the sacred Mother Tree and shared my words with her because she is so old that her roots probably connect to all the other trees in the forest through their underground mycorrhizal networks. When the wind picked up, I imaged she was sharing my message through her leaves with forests further away, who then sent the message through the sky to the trees where my friend was ailing. They sang to her in the movement of their leaves, and brought her something she needed, perhaps only a word or a soothing sound, that calmed her fears and allowed her to sleep for a couple of hours.Does my talking to the trees, or lighting candles, change anything? Does prayer? Prayer is a mode of communication, not a vending machine. God is not our butler, hanging around waiting to do our bidding. But if I ask God for advice, and I hear back that I should talk to the trees, who am I to argue?

Some of you may remember Clint Eastwood singing “I Talk to the Trees” in the movie Paint Your Wagon. Contrary to his experience, I think that trees do listen.

My spirit says yes, that talking to trees helps, but my logical brain wants something more solid. Here it is. If I’m outside talking to the trees and the branches are moving, and the person I want to help knows that I’m doing this, and the branches in the trees around her are moving, this makes a difference to her. I know that I would be touched if someone were talking to the trees on my behalf. It’s the same feeling if someone knows that I am going to light a candle for her 7 p.m. and pray for her for ten minutes. During that time, she feels my presence. Even though we’re separated by distance, we’re connected by spirit.

The Buddhists have a meditation (tonglen) that is like my tree talking. They sit in a room together and focus on generating compassion. When they have kindled enough compassion, they send waves of it out to those who need it, people who probably aren’t even aware of this happening. Their belief is that this makes a difference in people’s lives.

Maybe something is going on in the physical world that we can’t see. Maybe trees release specific pheromones into the air and this is how they communicate with each other. A lot of things happen in life that I can’t explain. At the very least, doing something like generating compassion, lighting candles, or talking to trees, changes us and opens our heart to the suffering of others.

If you fill yourself with compassion and go out among people, they will “feel” peacefulness coming from you, from the look in your eyes to your relaxed manner of walking, and they will feel more peaceful themselves. You know how seeing someone with a beaming smile makes you feel good? It’s like that. We become the compassion.

When we hear of someone who is struggling, we instinctively want to do something. So do SOMETHING, even if it’s just talking to the trees.

September 14, 2025

Living in the Twilight

Kate Bowler, Everything Happens For a Reason And Other Lies I’ve Loved, 2018

Having cancer isn’t funny, but that doesn’t mean we have to stop telling jokes.

What makes Bowler’s book significant in the world of books about cancer is that she is dying and she’s not. She has Stage 4 colon cancer that is being held at bay by experimental chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and lives two months at a time, from one checkup to the next. If the checkup is good, then she knows she has two more months of life. If it’s not, then she knows to start saying goodbye.

What’s different is her timeline. When you’re diagnosed with cancer, you generally have a number of years as doctors diagnose and treat you. If you are Stage 4, there are drugs that can keep you alive for five years or more. Bowler was given a 30% chance of lasting just two years. She says there’s a cost to living with this kind of stress, which intensifies as she gets closer to the time for her next scan.Colon cancer is the fourth leading cause of death among American women. Among the causes is a diet high in processed red meats, and having the Lynch syndrome, an inherited genetic disorder. After I developed prostate cancer, I took up my cancer center’s offer to be genetically tested to see if I had inherited a gene for prostate cancer as well as any of the other seventy know cancer-causing genes. I asked my geneticist to look specifically for the Lynch gene because my grandmother had colon cancer, along with breast cancer, as did two of my aunts. When I found out I didn’t, I breathed a deep sigh of relief.

Bowler is a professor of religious history at Duke Divinity School and has studied the Christian prosperity gospel. This theology says that if you are right with God, the proof will be that you are healthy, have money, a great family, and will prosper in your work. The flip side is that if you get sick, are poor, or stuck in a job you hate, then you are an unrepentant sinner and aren’t trusting God enough, even if you happen to be one of the pastors who preached this theology and was in his 40s when he died. It’s cause-and-effect. I don’t know how they explain a child getting cancer without their feet getting tangled up.

Prosperity Christians like to say that getting cancer is part of God’s plan, and many of them have said to Bowler that there is logic and meaning to her getting cancer and possibly dying — either it’s to inspire others with her noble struggle, or there is a divine lesson that she needs to learn. I’m not going to get into the particulars of this, other than to say that I don’t think God cares about material possessions. I don’t believe that God gives us cancer as a punishment. I think God values community, compassion, and helping one another, including those with cancer.

Bowler’s long-term maybe-dying, maybe-not-today, cancer has freed her from her shoulds so that she can just be herself, including laughing in public at inappropriate times (There’s a lot of humor in the book. For example, she took up swearing for Lent.) I’m drawn in when she says she’s living in a time suspended between life and death. This is what people with cancer discover. Our focus shifts from always planning for the future to living fully in this moment. We realize that the only thing we can be sure of is that we have today to take care of those we love, because tomorrow one of us may not be here.

Facing the possibility of dying is hard, at any age and for whatever reason, because we are facing the stark reality of ceasing to exist. It’s also hard on our support crew to suspend their dread of what might happen and not screw up their faces as they try to smile while being deathly concerned.

What is needed when someone is living with cancer, Bowler says, are not words but touch — the power of a hand holding ours, a hand on the back, the warmth of a long hug, the comfort of someone’s presence as we sit together and share coffee. This makes a big difference because it means that we’re not traveling though this wilderness without caffeine.

September 8, 2025

On Dying and Cancer

Atul Gawande, Being Mortal, 2014; Complications, 2002; Rana Awdish, In Shock, 2017.

Effective health care begins when patients feel their concerns are being heard and they are involved in deciding their course of treatments. Atul Gawande’s books speak of the need for patients to feel empathy from their doctors, and of the challenges that doctors face to provide the right care. He writes eloquently from the doctor’s perspective and tells stories in a narrative voice rather than using the language of clinical reports that cite case studies. Doctors and nurses find in him a kindred voice.

Atul Gawande is a medical doctor and surgeon. In Being Mortal, he talks about how doctors, the medical system, and nursing homes deal with end of life matters, and says they are missing the boat when they focus on the disease instead of the person.If you have metastatic cancer and are being maintained by drugs, there comes a time when the notion of dying changes in your mind from being a possibility to being reality. From what friends have said, when you are metastatic, you live on hope, praying for an experimental drug to come out of cancer research that will keep you alive.

Gawande says doctors used to be the benevolent Dr. Knows Best, the paternalistic model of medical care, and many still are. We took the red pill because the doctor told us to. Then a shift in medicine took place and they became Dr. Information. They presented the medical options and made us choose one. Besides the red pill, they now let us know there was also a blue pill and a yellow pill.

Now more doctors are listening to their patients, so there is shared-decision making. The doctor tells you about each option with its different benefits and risks, asks what you like and dislike about each, asks what you value the most, and then you make a decision together about what to do. This takes more time, of course, and some doctors are too busy, or tied up in their egos, to listen, especially if they work for a business group that pushes them to handle more patients every day.

He notes that patients sometimes have to be steered away from making bad decisions because they are fearful or frustrated. If we knew that we had limited time left (and doctors need to be upfront with us about this), most of us would live the rest of our lives differently. If we had the choice between three good months of life doing what brought us joy and pleasure, versus five months of pain from additional medical procedures that offered only marginal benefits, I think that many of us would choose the three good months, yet some would choose the pain route only because it offered the possibility of a slightly longer life.

Gawande says that nursing homes are moving away from hospital-like maintenance of people where everyone eats, sleeps, and takes pills at the same time (which is an improvement on the warehousing of people in poor houses) to where people have privacy, community with others in a relaxed setting, and the right to decide when they want to get up, eat, and go to bed.

Even if we don’t have cancer, we know that at some point in our latter years, we will need the help of someone to get through each day, whether this help comes from family, a live-in person, an assisted living facility, or hospice. Most of us don’t want to face the nuts and bolts of what to do when we’re dying until we’re forced to, and then our options may be limited.

I’m a supporter of palliative care and hospice because my father benefited from both. When he could no longer take care of himself at home after mom died, he let us move him into an assisted living facility where he had his own room. He had time to wrap his life up and finish his projects. When it was time to enter hospice care, he didn’t fight us because he understood that he fit the criteria, and hospice provided enough medication to keep his pain at bay.

Not surprisingly, hospice patients, with the same diagnosis as patients who continue with surgery and experimental medical treatments, tend to live longer and be happier.

*

In his earlier book Complications, from 2002, about how even experienced surgeons, supported by the latest diagnostic technology, make honest mistakes in judgement because the human body is a complex of interconnected systems, Gawande includes a chapter that discusses who controls your body and decides on treatments – the doctor or the patient. He references a 1984 book by ethicist and doctor Jay Katz, The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. What is at play here is that treatment decisions are not just about what is medically prudent, there are also personal issues involved, and no doctor is an authority on this. Gawande says that when he was in training in the early 1990s, he was taught that doctors work for the patient.

The doctor-patient decision sharing has advanced some, but in Dr. Rana Awdish’s superb 2017 book, In Shock, written fifteen years later, she details her near-fatal experience as a patient with multiple organ failures when doctors wouldn’t listen to her as she described her symptoms with medical precision, so she pushed back and fought with them to care for her as a person and not as a case study.

After a lifetime of making our own decisions, we’re reluctant to give up our independence when we become old or are dying. We want to keep the right to make the decisions about what happens to us. First we have to know what the choices are, and we need doctors who are willing to sit down with us and listen.

(An earlier version of this was published on my grief blog in 2018.)

September 1, 2025

Prostate Distillate

If you’re a man, you have a 1 in 8 chance of developing prostate cancer at some point. (Women have a 1 in 8 chance of developing breast cancer.) This will generally happen when you’re older, and in most cases, it will be so slow growing that you will die of something else before your prostate becomes a problem. That’s good news.

It’s still shocking to hear the doctor say you have cancer. My annual PSA test came back with a number that was much higher than the year before, so I knew something was afoot. The news surprised me because I had no physical symptoms of a problem. I expected to end up in the large “we’ll watch to see if anything changes” group that most men are in where nothing needs to be done.

After a number of finger palpitations over the months (the dreaded DREs, digital rectal exams) and a series of scans (bone, CT, PSMA-PET), a biopsy revealed that I had an aggressive form of the cancer. I didn’t have the option of doing nothing. My choice was either surgery to remove the prostate or a combination of hormone chemotherapy and two types of radiation.Not knowing anyone who had prostate cancer, when I casually mentioned this to my male friends, I was surprised to hear how many of them had already been flagged by their doctors and were being monitored. They hadn’t spoken of this before, as if it was an embarrassing secret. But then men, as well as women, don’t generally talk openly about any significant health matter that affects their lives. It would be easier on us if we shared what was going on and had the ongoing support of a group of people.

No cancer is good to have. My friend Michael says that if you’re a man and are going to get cancer, this is the kind to get because it’s treatable and curable, especially if it’s caught early, so I’m not likely to die from it. That’s good news, too. But did we catch my cancer early enough?

Researchers are looking into what causes prostate cancer to set up shop, but the findings so far are so ubiquitous that they don’t offer anything useable. Genetic screening can tell us who is most likely to develop cancer, but it can’t say if any of these people will. I’ve looked at the stats and know that after I’ve taken care of this cancer, when doctors say “there’s no evidence of any cancer remaining,” there’s a thirty percent chance of it coming back.

While both of my choices had comparable, positive outcomes, what I worried about most, outside of the pain and discomfort of the procedures themselves, were the effects of the treatments on my body. Incontinence and erectile dysfunction are common for those who have surgical removal. There are more bowel and bladder complications with radiation.

Three years later, my treatments are over. I had brachytherapy, where eighteen radioactive needles were inserted into my prostate for a time, then five weeks of daily radiation. Hormone chemotherapy started off with Casodex and then Lupron, and I’m still dealing with the aftereffects and side effects of all of this. While some disruptions have gone away, others have not, and my doctors tell me to give them more time to fade away. While my PSA has remained low, it continues to go up and down, and not all of the categories on my blood tests have returned into normal ranges, especially those replenished by my bones. I will have to wait to see if all of my body’s regulatory and metabolic systems reset, and wait longer to find out if my cancer is truly gone.

Rather than dying in old age as body parts wear out, I have something that might end me sooner. There is anticipatory grief in this because of the dreaded “what ifs” — what if I only have five years left to live? What if I’m left with physical limitations that I have to deal with every day?

Cancer will forever be a horse that is grazing in the back meadow.

August 28, 2025

The Poetry of Cancer

When we are dying from cancer and facing the end of our life, our senses sharpen and words distill into images and metaphors of poetry.

Not all of us are poets, of course, and not all of us would take time away from living our last months to look for the words to express what we are feeling and thinking. Rather than write, we may want to complete items from our bucket list that we’ve kept putting off, or focus on sharing everything we’ve learned about life with our children. Maybe we want to stop trying to achieve goals and simply enjoy each day free of outside expectations.

Do normal days ever exist again after a doctor says you have cancer?Two poets who did spend time finding the words came to my attention because of nonfiction writers I know who were their friends—Suzanne Roberts with the poet Ilyse Kusnetz, who wrote Angel Bones, and Wendy Fontane with the poet Julie Hungiville Lemay, who wrote The Echo of Ice Letting Go. Both are superb books.

Both poets write about their fears for the reality facing them. They speak about the unknowns, the what ifs, the maybes and perhaps, and try to make sense of them because they want to understand, and words help them do this. They explore the back rooms and dark corridors of diagnosis and treatment as they try to live each day to the fullest without thinking about how many more days they might have. Their books are honest and draw on images from nature.

Most of us go through life with the illusion of endless time. If we don’t feel like doing something today, we figure we always have tomorrow, next week, or twenty years in the future. Yet Kusnetz and Lemay were not old when they died—they were 50 and 64. One died of breast cancer and the other of ovarian cancer.

Ilyse Kusnetz believed that for grief to be more than suffering and be transformative, it needed to be shared. She says, “Poetry is the closest grief has to expression in language.”

Paraphrasing her—Even if sorrow lives like a seed inside beauty, we know it cannot last. May beauty fill the unexpected vistas of your life, and may you be opened by it to the world and to each other. (3) “The river is a green heaven, the body / a refuge, the current a blessing.” (52) And, in her parting words in the book, she wanted her family and friends to know that after she was physically gone, she would still be transmitting. (77)

Writing allowed Julie Hungiville Lemay to understand her life before diagnosis, and helped her accept her new path. She saw the truth of life with clarity, like the view of the mountain in the distance on an utterly clear day. Cancer’s removal of long-term goals helped Lemay live in this moment more attuned to the particulars around her, and spurred her to be open and honest with others. As she dealt with the reality of her approaching death, she listened to the Alaskan wilderness in her hours of solitude, saw how death was a natural part of life, and found the reassurance and solace she needed.

Many of her lines of poetry made me pause: “She wants you to know / this place of her. She holds / the dark fragrance in her bright palm, / leaves as small and infinite as stars.” (30) “In the distance, / the glacier calves / … / I listen to the sound of the water, / the echo of letting go.” (42) “There is loneliness in not knowing, in being / unable to read the secret / of open skies …” (93) “Bury me to the sky. / Let my bones be alms / for the birds.” (94)

May each of us face our own cancer honestly, with hope and with courage.

(This post first appeared on my grief blog in 2020.)

August 10, 2025

John Donne and Cancer

In 1993, Margaret Edson wrote a play called Wit that talks about the experience of having cancer and going through chemotherapy. In the early 1990s, discussions like this were not common. The play tells the story of Vivian Bearing, an English professor, who is diagnosed with Stage 4 ovarian cancer that has metastasized. It’s not surprising that Bearing would be Stage 4 because there is still no method of screening for this cancer. In the play, Bearing knows there is a problem when her abdominal pain doesn’t go away. The oncology doctor puts her through eight rounds of toxic chemotherapy, and Bearing describes the procedures, their invasiveness, the indignities of being treated like a test subject and not a person, the nausea, her growing weakness, the shaking, and always feeling cold.

Bearing is under the care of the chief oncologist as well as his resident oncologist who is more interested in research results than in how she is physically and emotionally coping. To him, she is a lab rat and he wants to gather as much data as he can before she dies. Bearing is also tended to by Susie, an RN, who cares for Bearing as a person and eases her suffering. Susie tries to tell the doctor that Bearing had a DNR when she goes into cardiac arrest, but the doctor brushes her off and calls a Code Blue.

Besides presenting how it feels to have terminal cancer, what also caught my interest was the discussion of John Donne’s Holy Sonnets. Bearing loves the wit in Donne’s language and quotes passages from the poems. A student in one of her classes once asked why Donne doesn’t simply share his insights about Death rather than coding his messages in wit. Bearing thinks that his wit is not simply a literary style but the key to figuring out Donne’s puzzles, and finding those answers takes on more urgency as she slides closer to death.

Her mentor, however, while she thought death was a subject worthy of contemplation, did not regard Donne’s poems as puzzles to be figured out. I think that for Donne language was his medium for working out his grief over his wife’s passing and understanding death. Being witty and playing with the language allowed him to regain some control.

Bearing uses Donne’s poems to joust with her chemotherapy, and they offer her an escape from pain and a place of refuge. Near the end, when she challenges the resident doctor to set his research aside and treat her like a human being who has feelings, she has an awakening and realizes that she acted the same way in her classes, preferring scholarship to interacting with her students and caring about what was going on in their lives.

When my wife Evelyn died unexpectedly in her 40s, I struggled with what seemed like the arbitrariness of Death, and I found refuge in Donne’s poetry, especially his Holy Sonnets. I didn’t understand then, for example, what Donne meant when he said he believed the death of a loved one was not a breach between two people, but an expansion, like gold that is beaten into airy thinness. I was miserable and it felt like the rhino of grief was sitting in my living room, and there was nothing golden or airy about that. But a year later I came to understand it when I felt Evelyn’s presence beside me when hiking in Yosemite.

The play illustrates the tension that exists in the medical world between advancing science through research to help others later on and caring for patients who are suffering now. What the patient wants should always come first because it’s their body. Research comes second. Once it was discovered that Bearing’s chemotherapy wasn’t affecting the areas that had metastasized, it should have been discontinued.

I know men with prostate cancer who were on leuprolide, an anti-hormone drug, that was so disruptive of their daily lives that after two years on it they told their doctors they weren’t going to take it anymore.

For medical people, the lesson is to listen to their nurses and listen to what your patients are telling you about their bodies. For patients, the message is that you are the one who decides what is done to you, and that you have to advocate for what you want.

(Some of my words about Donne were first published as “John Donne and the Rhino of Grief” in the Antler Journal, 2014.)

June 28, 2025

The Healing of Therapeutic Massage

I’m delighted that my short essay “After Cancer Treatment, a Restorative Touch,” on the healing power of therapeutic massage for cancer patients, is published in the July issue of American Journal of Nursing. Because it’s available only to subscribers, I’m unable to include a link so that you can read it. This kind of therapy was invaluable for me because it gave me my body back.After the physical trauma and pain of months of treatments for prostate cancer, my body was in sad shape. A nurse signed me up for a new oncological massage program at the cancer center. Having someone treat my body with kindness instead of causing more pain was an enormous relief. The months of probings, blood tests, biopsies, insertion of radioactive wires, weeks of photon radiation, and the hormonal and systemic disruptions caused by 18 months on the leuprolide drug, whose aftereffects were still affecting me, the therapist smoothed out the tightness, aches, and strains in the muscles I had left. Her work enabled me to continue with the yoga classes I recently began to get my strength back.

When you have cancer, your doctors work to combine and coordinate therapies to kill the cancer. How your body feels while they are doing this is not their primary focus. What your emotions are doing is also not their primary focus. They do care about both of these, of course, and if you mention that you are struggling with one of them, they will find a way to make you more comfortable.

One of the positive shifts I see happening, and I may be wrong because it seems to be a new thing in two of the three cancer facilities I’m familiar with (the third doesn’t offer it), is that more cancer places are providing massage therapy. As a patient, you lose much of your strength, coordination, and flexibility because of the disruptions and length of cancer treatments, and your muscles cramp and become tight from simple exertions. Therapeutic massage helps you move through the day feeling good.

I hope that therapeutic massages become standard offerings in all cancer centers.

After Cancer Treatment, a Restorative TouchMay 24, 2025

Biden and Prostate Cancer

By now you’ve heard that Joe Biden has prostate cancer. Even if you don’t know what this means, where the prostate is or what it does, you should realize that his cancer is serious and he will die without treatment.

What I know about Biden’s cancer is that it has a Gleason 9 score and is Grade 5, which means that it’s fast growing and aggressive. It is not the slow-growing kind that 80% of American men get. Apparently, he was having urinary problems, which is common for older men, and went to a doctor to get it checked out.

The cancer has also metastasized in his bones which means that a cure is not in the picture. The good news is that his cancer is hormone-sensitive so it can be effectively treated by anti-hormone therapies. And because of cancer research, there are now targeting therapy drugs that could also prolong his life.I don’t know what diagnostic tests were done. I do know that the PSA, which is the first test used to check for prostate cancer, is not often done on men who are over the age of 70. Biden is 82. My primary physician, Dr. Farhana Khan, runs the PSA blood test every year as part of my physical. The year before I had cancer, my PSA was normal. A single year later, my PSA was high and a biopsy indicated it was Gleason 9 and Grade 5, the same numbers as Biden’s. Although I had no symptoms of any problem, if I had waited until I did, my aggressive cancer would probably have metastasized into my bones or lymph nodes. I was in my 60s at the time, and I thanked her profusely.

Every cancer is serious, and it shares the shit out of us. It doesn’t matter if you have breast, prostate, pancreatic, ovarian, blood, or another kind of cancer, even if it’s successfully treated, you are going to have to live with the fear of it coming back for the rest of your life, because it does for many people. I’m beginning to think that “remission” is a more accurate term than “cure.”

If there is a history of prostate cancer in your family, or if you are African American, get tested before you’re 50. Mark Shanahan’s father had prostate cancer that he never talked about because older men don’t talk about cancers that involve their genitals. Younger men don’t talk about having prostate cancer with each other, either, so Shanahan had little idea about what he was in for when he was diagnosed. He was 48. I’ll probably be writing more about him in the future.

Give your father a PSA for Father’s Day. Well, not you personally, but if he hasn’t been tested in a year, make an appointment for him with his doctor. If his doctor won’t do a PSA, find a different doctor. This is your father’s life that we’re talking about.

April 27, 2025

Breast Cancer and the Health Care System

Anne Boyer’s book about surviving aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, The Undying, takes the reader inside what it feels like to endure chemotherapy without any promise of surviving. Boyer covers a wide range of topics—the physical suffering, fears about dying, coping with the pain, research into the medical treatments, the philosophy and history of breast cancer procedures, and the social inequalities of a for-profit health care system and the politics of care.Stage 4 triple-negative breast cancer is not curable, but it is treatable, and cancer research is finding new ways to further survival. It has a high risk of recurrence. Chemotherapy offered Boyer a chance to life, although it would extract a toll on her body. Boyer survived, but the chemo damaged the nerves that control her heart.

Among her many insights, she points out that while breast cancer treatments are often covered by insurance and your place of work, the time that is needed to recover from the long-term effects of surgery and therapy often are not, and women lose their jobs, their homes, and too often they lose touch with who they are. She also points out that while many organizations receive funding for cancer, too few dollars are allocated to research to prevent cancer from starting.

There are also paragraphs of circular thoughts when Boyer is trying to think her way through something, and this illustrates how chemo brains can get stuck in eddies of thoughts that circle around and around, trying to find a way out.

Boyer experiences the sorrow of losing friends who simply didn’t want to deal with cancer, and her joy of discovering other friends who stepped up to support and keep her going. Most of the chapters are short, as if they were taken from a journal that Boyer kept over the months of her diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. Here are some of her words:

“Sometimes to give a person a word to call their suffering is the only treatment for it.”

“After a cancer diagnosis, very little is ever itself again.”

“We are supposed to keep our unhappiness to ourselves but donate our courage to everyone.”

“Being sick makes excessive space for thinking, and excessive thinking makes room for thoughts of death.”

“Some of us who survive the worst survive it into bare inexistence.”

“Pain doesn’t destroy language: it changes it.”

“when I was at my lowest, what I needed most was art—not comfort”

“Recovery is tough and often lonely.”