Alexandra Sokoloff's Blog, page 13

December 6, 2016

Nanowrimo Now What?

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

YAY!!! You survived! Or maybe I shouldn’t make any assumptions, there.

But for the sake of argument, let’s say you survived, not only what was arguably the worst November in modern history, but Nanowrimo, too, and now have a rough draft (maybe very, very, very rough draft) of about 50,000 words.

What next?

Well, first of all, did you write to “The End”? Because if not, then you may have survived, but you’re not done. You must get through to The End, no matter how rough it is (rough meaning the process AND the pages…). If you did not get to The End, I would strongly urge that you NOT take a break, no matter how tired you are (well, maybe a day). You can slow down your schedule, set a lower per-day word or page count, but do not stop. Write every day, or every other day if that’s your schedule, but get the sucker done.

You may end up throwing away most of what you write, but it is a really, really, really bad idea not to get all the way through a story. That is how most books, scripts and probably most all other things in life worth doing are abandoned.

Conversely, if you DID get all the way to “The End”, then definitely, take a break. As long a break as possible. You should keep to a writing schedule, start brainstorming the next project, maybe do some random collaging to see what images come up that might lead to something fantastic - but if you have a completed draft, then what you need right now is SPACE from it. You are going to need fresh eyes to do the read-through that is going to take you to the next level, and the only way for you to get those fresh eyes is to leave the story alone for a while.

In the next month I'll be posting about rewriting. But not now.

First, no matter where you are in the process, celebrate! You showed up and have the pages to show for it.

Then -

1. Keep going if you’re not done

OR

2. Take a good long break if you have a whole first draft, and if you MUST think about writing, maybe start thinking about another project.

And in the meantime, I’d love to hear how you all who were Nanoing did.

- Alex

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

YAY!!! You survived! Or maybe I shouldn’t make any assumptions, there.

But for the sake of argument, let’s say you survived, not only what was arguably the worst November in modern history, but Nanowrimo, too, and now have a rough draft (maybe very, very, very rough draft) of about 50,000 words.

What next?

Well, first of all, did you write to “The End”? Because if not, then you may have survived, but you’re not done. You must get through to The End, no matter how rough it is (rough meaning the process AND the pages…). If you did not get to The End, I would strongly urge that you NOT take a break, no matter how tired you are (well, maybe a day). You can slow down your schedule, set a lower per-day word or page count, but do not stop. Write every day, or every other day if that’s your schedule, but get the sucker done.

You may end up throwing away most of what you write, but it is a really, really, really bad idea not to get all the way through a story. That is how most books, scripts and probably most all other things in life worth doing are abandoned.

Conversely, if you DID get all the way to “The End”, then definitely, take a break. As long a break as possible. You should keep to a writing schedule, start brainstorming the next project, maybe do some random collaging to see what images come up that might lead to something fantastic - but if you have a completed draft, then what you need right now is SPACE from it. You are going to need fresh eyes to do the read-through that is going to take you to the next level, and the only way for you to get those fresh eyes is to leave the story alone for a while.

In the next month I'll be posting about rewriting. But not now.

First, no matter where you are in the process, celebrate! You showed up and have the pages to show for it.

Then -

1. Keep going if you’re not done

OR

2. Take a good long break if you have a whole first draft, and if you MUST think about writing, maybe start thinking about another project.

And in the meantime, I’d love to hear how you all who were Nanoing did.

- Alex

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on December 06, 2016 06:34

November 30, 2016

NANOWRIMO: Act III Questions and Prompts

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Yes, we're into Act III, now. Or maybe you're not that far yet, which is all perfectly fine. Personally, I know my endgame, but I needed to stop and go back over some earlier things before I push through to the end. I'm still well over 50,000 words. Just remember, as long as you're writing, it's all good. The book will be done when it's done.

But if you are into Act III, here are the prompts for that last act.

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

- Alex

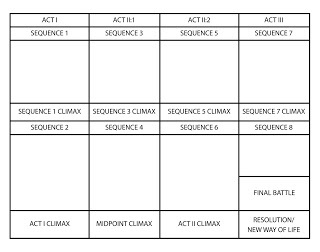

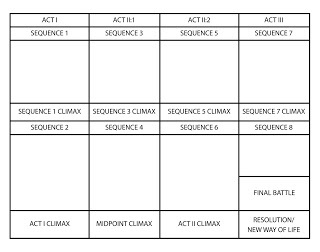

ELEMENTS OF ACT THREE

The third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often be one continuous sequence —the chase and confrontation, or confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle, or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (Storming the Castle): Sequence 7.2. The final battle itself: Sequence 8.

• In addition to the FINAL PLAN, there may be another GATHERING OF THE TEAM scene and a brief TRAINING SEQUENCE.

• There may well be DEFEATS OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS

Each one of the secondary opponents should be given a satisfying end or comeuppance. (This may also happen earlier, in Act II:2.)

• THEMATIC LOCATION

This is often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare.

We see:

• THE PROTAGONIST’S CHARACTER CHANGE

• THE ANTAGONIST’S CHARACTER CHANGE (if any)

• Possibly ALLY/ALLIES’ CHARACTER CHANGE and/or GAINING OF DESIRE(s)

• Possibly a huge FINAL REVERSAL OR REVEAL (twist), or even a whole series of PAYOFFS that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and It’s a Wonderful Life)

• RESOLUTION: A glimpse into the NEW WAY OF LIFE that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it

• Possibly a sense of coming FULL CIRCLE

Returning to the opening image or scene, and is a great way to show how much things have changed, or how the hero/ine has changed inside, which makes her or him deal with the same place and situation in a whole different way.

• CLOSING IMAGE

What do you want to leave your reader or audience with in the end?

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 14.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Yes, we're into Act III, now. Or maybe you're not that far yet, which is all perfectly fine. Personally, I know my endgame, but I needed to stop and go back over some earlier things before I push through to the end. I'm still well over 50,000 words. Just remember, as long as you're writing, it's all good. The book will be done when it's done.

But if you are into Act III, here are the prompts for that last act.

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

- Alex

ELEMENTS OF ACT THREE

The third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often be one continuous sequence —the chase and confrontation, or confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle, or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (Storming the Castle): Sequence 7.2. The final battle itself: Sequence 8.

• In addition to the FINAL PLAN, there may be another GATHERING OF THE TEAM scene and a brief TRAINING SEQUENCE.

• There may well be DEFEATS OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS

Each one of the secondary opponents should be given a satisfying end or comeuppance. (This may also happen earlier, in Act II:2.)

• THEMATIC LOCATION

This is often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare.

We see:

• THE PROTAGONIST’S CHARACTER CHANGE

• THE ANTAGONIST’S CHARACTER CHANGE (if any)

• Possibly ALLY/ALLIES’ CHARACTER CHANGE and/or GAINING OF DESIRE(s)

• Possibly a huge FINAL REVERSAL OR REVEAL (twist), or even a whole series of PAYOFFS that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and It’s a Wonderful Life)

• RESOLUTION: A glimpse into the NEW WAY OF LIFE that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it

• Possibly a sense of coming FULL CIRCLE

Returning to the opening image or scene, and is a great way to show how much things have changed, or how the hero/ine has changed inside, which makes her or him deal with the same place and situation in a whole different way.

• CLOSING IMAGE

What do you want to leave your reader or audience with in the end?

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 14.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 30, 2016 03:23

November 22, 2016

NANOWRIMO: Act II, Part 2 Questions and Prompts

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Okay, Nanos. While I am moving on to prompts for the second half of Act Two, remember that wherever you are in this process is just fine. Personally I think it would be a little crazy to be into the second half of the second act in three weeks!

So if you're not this far, just save this post for later.

(Personally, I've had to stop moving forward in this act on my own book (Book 5 in the Huntress series) to brainstorm ahead about the endgame. The good news is I have an endgame, now. The bad news is it reflects our world under the pussy grabber. But the books are about sexual predators and that's where we are - I can't pretend otherwise.)

A few general things about Act II, Part 2. This is almost always the darkest quarter of the story. While in Act II, Part 1, the hero/ine is generally (but not always) winning, after the Midpoint, the hero/ine starts to lose, and lose big. And also lose very fast. In fact, this is the quarter that is most often shortened if you are writing a shorter book or movie, because it's not all that hard and doesn't take all that much time to pull the rug out from your protagonist.

Just knowing that basic, very general distinction between the two halves of Act Two can be very, very useful.

But getting more specific...

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

(More on MIDPOINT).

Act II, part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud.

How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

More discussion on Elements Of Act II:2

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 14.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Okay, Nanos. While I am moving on to prompts for the second half of Act Two, remember that wherever you are in this process is just fine. Personally I think it would be a little crazy to be into the second half of the second act in three weeks!

So if you're not this far, just save this post for later.

(Personally, I've had to stop moving forward in this act on my own book (Book 5 in the Huntress series) to brainstorm ahead about the endgame. The good news is I have an endgame, now. The bad news is it reflects our world under the pussy grabber. But the books are about sexual predators and that's where we are - I can't pretend otherwise.)

A few general things about Act II, Part 2. This is almost always the darkest quarter of the story. While in Act II, Part 1, the hero/ine is generally (but not always) winning, after the Midpoint, the hero/ine starts to lose, and lose big. And also lose very fast. In fact, this is the quarter that is most often shortened if you are writing a shorter book or movie, because it's not all that hard and doesn't take all that much time to pull the rug out from your protagonist.

Just knowing that basic, very general distinction between the two halves of Act Two can be very, very useful.

But getting more specific...

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

(More on MIDPOINT).

Act II, part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud.

How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

More discussion on Elements Of Act II:2

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 14.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 22, 2016 00:26

November 13, 2016

Nanowrimo: Act Two, Part 1 Questions and Prompts

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Thank God for Nano. For once having a looming deadline is completely lifesaving. I literally can't think too much about this horror of an election for the next month.

I've hit 20,000 words today, been averaging 1700 words a day, and I know it's been keeping me from losing my mind completely.

Maybe in a month I'll be able to breathe again, and be able to act again.

In the meantime, I have a book to write. I have a cause to advance.

I understand if all you can do now is grieve. But if you're like me, and finding that writing is saving, I'll keep posting questions and prompts.

Remember, having a daily word count is great motivation, but this Nano deadline is only to help you write in a concentrated way. Don't beat yourself up if you're not hitting your word count - even when you're not writing, your subconscious is always working on your book for you and with you.

(Also, drink lots of water. It helps with ongoing symptoms of shock.)

And if you're stuck, try brainstorming on one of these questions.

ACT TWO, PART ONE

(Elements of Act I checklist is here).

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 400-page book it starts at about p. 100 and climaxes at about p. 200.

Act II, Part 1 is the most variable section of the four sections of a story. I have noticed it also tends to be the most genre-specific. It doesn’t have the very clear, generic essential elements that Act I and Act 3 do – except in the case of Mysteries and certain kinds of team action films, which generally have a more standard structure in this section.

IF THE FILM IS A MYSTERY, this section will almost always have these elements:

-QUESTIONING WITNESSES

-LINING UP AND ELIMINATING SUSPECTS

-FOLLOWING CLUES

-RED HERRINGS AND FALSE TRAILS

-THE DETECTIVE VOICING HER/HIS THEORY

IF THE FILM IS A TEAM ACTION STORY, A WAR STORY, A HEIST OR CAPER MOVIE (like OCEAN’S 11, THE SEVEN SAMURI, THE DIRTY DOZEN, ARMAGGEDON and INCEPTION) then this section will usually have these elements:

- GATHERING THE TEAM

- TRAINING SEQUENCE

- GATHERING THE TOOLS

- BONDING BETWEEN TEAM MEMBERS

- SETTING UP TEAM MEMBERS’ STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES that will be tested in battle later.

There may also be

- A MACGUFFIN

- A TICKING CLOCK

But if the story is not a mystery or a team action story, the first half of Act 2 will often have some of the above elements, and ALL stories will generally have these next elements in Act II, part 1 (not in any particular order):

- CROSSING THE THRESHOLD/ENTERING THE SPECIAL WORLD

(This scene may already have happened in Act One, but it often happens right at the end of Act One or right at the beginning of Act Two.) How do the storytellers make this moment important? Is there a special PASSAGEWAY between the worlds?

- THRESHOLD GUARDIAN (maybe)

There is very often a character who tries to prevent the hero/ine from entering the SPECIAL WORLD, or who gives them a warning about danger.

- HERO/INE’S PLAN

- What is the hero/ine’s PLAN to get what s/he wants?

The plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the hero/ine start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail.

- THE ANTAGONIST’S PLAN

Same as for the hero/ine: the plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the villain start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail. Even if the villain is being kept secret, we will see the effects of the villain's plan on the hero/ine.

- ATTACKS AND COUNTERATTACKS

How do we see the antagonist attacking the hero/ine?

Whether or not the hero/ine realizes who is attacking her or him, the antagonist (s) will be nearby and constantly attacking the hero/ine. How does the hero/ine fight back?

- SERIES OF TESTS

How do we see the hero/ine being tested?

In a mentor story, the mentor will often be designing these tests, and there may be a training sequence or training scenes as well. Sometimes (as in THE GODFATHER) no one is really designing the tests, but the hero/ine keeps running up against obstacles to what they want and they have to overcome those obstacles, and with each win they become stronger.

The hero/ine USUALLY wins a lot in Act II:1 (and then starts to lose throughout Act II:2), but that’s not necessarily true. In JAWS, Sheriff Brody doesn’t get a win until the big defeat of the Midpoint, when he is finally able to force the mayor to sign a check and hire Quint to kill the shark.

- BONDING WITH ALLIES – LOVE SCENES

This is one of the great pleasures of any story – seeing the hero/ine make lifelong friends or fall in love. Besides the more obvious romantic scenes, the love scenes can be between a boy and his dragon, as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON; or between teammates, as in JAWS; or a man and his father or a woman and her mother (some of the most successful movies, like THE GODFATHER, HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, TERMS OF ENDEARMENT and STEEL MAGNOLIAS show these dynamics). What are the scenes that make us feel the glow of love or joy of friendship?

Or in darker stories, instead of bonding scenes, the storytellers may show the hero/ine pulling away from people and becoming more and more alienated, as in THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, THE SHINING, CASINO.

In a love story, there is always a specific scene that you might call THE DANCE, where we see for the first time that the two lovers are perfect for each other (this is often some witty exchange of dialogue when the two seem to be finishing each other’s sentences, or maybe they end up forced to sing karaoke together and bring down the house…). You see this Dance scene in buddy comedies and buddy action movies as well.

- GENRE SCENES (action, horror, suspense, sex, emotion, adventure, violence)

Act II, part 1 is the section of a story that will really deliver on THE PROMISE OF THE PREMISE.

What is the EXPERIENCE that you hope and expect to get from this story? – is it the glow and sexiness of falling in love, or the adrenaline rush of supernatural horror, or the intellectual pleasure of solving a mystery, or the vicarious triumph of kicking the ass of a hated enemy in hand-to-hand combat?

Here are some examples:

- In THE GODFATHER, we get the EXPERIENCE of Michael gaining in power as he steps into the family business. There’s a vicarious thrill in seeing him win these battles.

- In JAWS, we EXPERIENCE the terror of what it’s like to be in a small beach town under attack by a monster of the sea.

- In HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, we get the EXPERIENCE and wonder of discovering all these cool and endearing qualities about dragons, including and especially the EXPERIENCE of flying. We also get to EXPERIENCE outcast and loser Hiccup suddenly winning big in the training ring.

- In HARRY POTTER (1), we get the EXPERIENCE of going to a school for wizards and learning and practicing magic (including flying).

(I want to note that for those of you working with horror stories, it’s very important to identify WHAT IS THE HORROR, exactly? What are we so scared of, in this story? How do the storytellers give us the experience of that horror?)

Ask yourself what EXPERIENCE you want your audience or reader to have in your own story, then look for the scenes that deliver on that promise in Act II, part 1. Well, do they? If not, how can you enhance that experience?

And another big but important generalization I can make about Act II, part 1, is that this is often where the specific structure of the KIND of story you’re writing (or viewing) kicks in. For more on identifying KINDS of stories, see What Kind Of Story Is It?

Act II part 1 builds to the MIDPOINT CLIMAX – which in movies is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

More discussion on Elements of Act Two.

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 13.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon US

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Thank God for Nano. For once having a looming deadline is completely lifesaving. I literally can't think too much about this horror of an election for the next month.

I've hit 20,000 words today, been averaging 1700 words a day, and I know it's been keeping me from losing my mind completely.

Maybe in a month I'll be able to breathe again, and be able to act again.

In the meantime, I have a book to write. I have a cause to advance.

I understand if all you can do now is grieve. But if you're like me, and finding that writing is saving, I'll keep posting questions and prompts.

Remember, having a daily word count is great motivation, but this Nano deadline is only to help you write in a concentrated way. Don't beat yourself up if you're not hitting your word count - even when you're not writing, your subconscious is always working on your book for you and with you.

(Also, drink lots of water. It helps with ongoing symptoms of shock.)

And if you're stuck, try brainstorming on one of these questions.

ACT TWO, PART ONE

(Elements of Act I checklist is here).

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 400-page book it starts at about p. 100 and climaxes at about p. 200.

Act II, Part 1 is the most variable section of the four sections of a story. I have noticed it also tends to be the most genre-specific. It doesn’t have the very clear, generic essential elements that Act I and Act 3 do – except in the case of Mysteries and certain kinds of team action films, which generally have a more standard structure in this section.

IF THE FILM IS A MYSTERY, this section will almost always have these elements:

-QUESTIONING WITNESSES

-LINING UP AND ELIMINATING SUSPECTS

-FOLLOWING CLUES

-RED HERRINGS AND FALSE TRAILS

-THE DETECTIVE VOICING HER/HIS THEORY

IF THE FILM IS A TEAM ACTION STORY, A WAR STORY, A HEIST OR CAPER MOVIE (like OCEAN’S 11, THE SEVEN SAMURI, THE DIRTY DOZEN, ARMAGGEDON and INCEPTION) then this section will usually have these elements:

- GATHERING THE TEAM

- TRAINING SEQUENCE

- GATHERING THE TOOLS

- BONDING BETWEEN TEAM MEMBERS

- SETTING UP TEAM MEMBERS’ STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES that will be tested in battle later.

There may also be

- A MACGUFFIN

- A TICKING CLOCK

But if the story is not a mystery or a team action story, the first half of Act 2 will often have some of the above elements, and ALL stories will generally have these next elements in Act II, part 1 (not in any particular order):

- CROSSING THE THRESHOLD/ENTERING THE SPECIAL WORLD

(This scene may already have happened in Act One, but it often happens right at the end of Act One or right at the beginning of Act Two.) How do the storytellers make this moment important? Is there a special PASSAGEWAY between the worlds?

- THRESHOLD GUARDIAN (maybe)

There is very often a character who tries to prevent the hero/ine from entering the SPECIAL WORLD, or who gives them a warning about danger.

- HERO/INE’S PLAN

- What is the hero/ine’s PLAN to get what s/he wants?

The plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the hero/ine start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail.

- THE ANTAGONIST’S PLAN

Same as for the hero/ine: the plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the villain start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail. Even if the villain is being kept secret, we will see the effects of the villain's plan on the hero/ine.

- ATTACKS AND COUNTERATTACKS

How do we see the antagonist attacking the hero/ine?

Whether or not the hero/ine realizes who is attacking her or him, the antagonist (s) will be nearby and constantly attacking the hero/ine. How does the hero/ine fight back?

- SERIES OF TESTS

How do we see the hero/ine being tested?

In a mentor story, the mentor will often be designing these tests, and there may be a training sequence or training scenes as well. Sometimes (as in THE GODFATHER) no one is really designing the tests, but the hero/ine keeps running up against obstacles to what they want and they have to overcome those obstacles, and with each win they become stronger.

The hero/ine USUALLY wins a lot in Act II:1 (and then starts to lose throughout Act II:2), but that’s not necessarily true. In JAWS, Sheriff Brody doesn’t get a win until the big defeat of the Midpoint, when he is finally able to force the mayor to sign a check and hire Quint to kill the shark.

- BONDING WITH ALLIES – LOVE SCENES

This is one of the great pleasures of any story – seeing the hero/ine make lifelong friends or fall in love. Besides the more obvious romantic scenes, the love scenes can be between a boy and his dragon, as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON; or between teammates, as in JAWS; or a man and his father or a woman and her mother (some of the most successful movies, like THE GODFATHER, HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, TERMS OF ENDEARMENT and STEEL MAGNOLIAS show these dynamics). What are the scenes that make us feel the glow of love or joy of friendship?

Or in darker stories, instead of bonding scenes, the storytellers may show the hero/ine pulling away from people and becoming more and more alienated, as in THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, THE SHINING, CASINO.

In a love story, there is always a specific scene that you might call THE DANCE, where we see for the first time that the two lovers are perfect for each other (this is often some witty exchange of dialogue when the two seem to be finishing each other’s sentences, or maybe they end up forced to sing karaoke together and bring down the house…). You see this Dance scene in buddy comedies and buddy action movies as well.

- GENRE SCENES (action, horror, suspense, sex, emotion, adventure, violence)

Act II, part 1 is the section of a story that will really deliver on THE PROMISE OF THE PREMISE.

What is the EXPERIENCE that you hope and expect to get from this story? – is it the glow and sexiness of falling in love, or the adrenaline rush of supernatural horror, or the intellectual pleasure of solving a mystery, or the vicarious triumph of kicking the ass of a hated enemy in hand-to-hand combat?

Here are some examples:

- In THE GODFATHER, we get the EXPERIENCE of Michael gaining in power as he steps into the family business. There’s a vicarious thrill in seeing him win these battles.

- In JAWS, we EXPERIENCE the terror of what it’s like to be in a small beach town under attack by a monster of the sea.

- In HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, we get the EXPERIENCE and wonder of discovering all these cool and endearing qualities about dragons, including and especially the EXPERIENCE of flying. We also get to EXPERIENCE outcast and loser Hiccup suddenly winning big in the training ring.

- In HARRY POTTER (1), we get the EXPERIENCE of going to a school for wizards and learning and practicing magic (including flying).

(I want to note that for those of you working with horror stories, it’s very important to identify WHAT IS THE HORROR, exactly? What are we so scared of, in this story? How do the storytellers give us the experience of that horror?)

Ask yourself what EXPERIENCE you want your audience or reader to have in your own story, then look for the scenes that deliver on that promise in Act II, part 1. Well, do they? If not, how can you enhance that experience?

And another big but important generalization I can make about Act II, part 1, is that this is often where the specific structure of the KIND of story you’re writing (or viewing) kicks in. For more on identifying KINDS of stories, see What Kind Of Story Is It?

Act II part 1 builds to the MIDPOINT CLIMAX – which in movies is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

More discussion on Elements of Act Two.

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 13.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon US

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Published on November 13, 2016 02:49

November 7, 2016

Nanowrimo: Act I questions and prompts

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Whew, what a week. Nano is completely saving my sanity in this excruciating run-up to the most important election of our lifetimes. I've been averaging 1700 words a day, and I know it's been keeping me from losing my mind completely. Every time I feel a wave of anxiety I make another donation to Hillary or Act Blue.

So hopefully you're on fire, living your Act I by now, right? This is the last day of the first week, so

today I wanted to post some questions and prompts that might be useful for to ask yourself as you wrap up Act One. Not that you HAVE to have finished Act One by the first week! Having a daily word count is great motivation, but this Nano deadline is only to help you write in a concentrated way. Dpn't beat yourself up if you're not hitting your word count - even when you're not writing, your subconscious is always working on your book for you and with you.

And if you're stuck, try brainstorming on one of these questions!

ELEMENTS OF ACT ONE:

- OPENING IMAGE/OPENING SCENE

Describe the OPENING IMAGE and/or opening scene of the story.

What mood, tone and genre does it set up? What kinds of experiences does it hint at or promise? (Look at colors, music, pace, visuals, location, dialogue, symbols, etc.).

Does the opening image or scene mirror the closing image or scene? (It’s not mandatory, but it’s a useful technique, often used.). How are the two different?

* What’s the MOOD, TONE, GENRE (s) the story sets up from the beginning? How does it do that?

* VISUAL AND THEMATIC IMAGE SYSTEMS

(More discussion here.)

* THE ORDINARY WORLD/THE SPECIAL WORLD

What does the ordinary world look and feel like? How does it differ in look and atmosphere from THE SPECIAL WORLD?

* MEET THE HERO OR HEROINE

How do we know this is the main character? Why do we like him or her? Why do we relate to him or her? What is the moment that we start rooting for this person? Why do we care?

• HERO/INE’S INNER AND OUTER DESIRE

What does the Hero/ine say s/he wants? Or what do we sense that s/he wants, even if s/he doesn't say it or seem to be aware of it? How does what s/he thinks s/he wants turn out to be wrong?

• HERO/INE’S PROBLEM

(This is usually an immediate external problem, not an overall need. In some stories this is more apparent than others.)

* HERO/INE’S GHOST OR WOUND

What is haunting them from the past?

• HERO/INE’S CHARACTER ARC

Look at the beginning and the end to see how much the hero/ine changes in the course of the story. How do the storytellers depict that change?

• INCITING INCIDENT/CALL TO ADVENTURE

(This can be the same scene or separated into two different scenes.)

How do the storytellers make this moment or sequence significant?

* REFUSAL OF THE CALL

Is the hero/ine reluctant to take on this task or adventure? How do we see that reluctance?

• MEET THE ANTAGONIST (and/or introduce a Mystery, which is what you do when you’re going to keep your antagonist hidden to reveal at the end).

How do we know this is the antagonist? Does this person or people want the same thing as the hero/ine, or is this person preventing the hero/ine from getting what s/he wants?

* OTHER FORCES OF OPPOSITION

Who and what else is standing in the hero/ine’s way?

• THEME/ WHAT’S THE STORY ABOUT?

There are usually multiple themes working in any story, and usually they will be stated aloud.

• INTRODUCE ALLIES

How is each ally introduced?

* INTRODUCE MENTOR (may or may not have one)

What are the qualities of this mentor? How is this person a good teacher (or a bad teacher) for the hero?

• INTRODUCE LOVE INTEREST (may or may not have one).

What makes us know from the beginning that this person is The One?

* ENTERING THE SPECIAL WORLD/CROSSING THE THRESHOLD

What is the Special World? How is it different from the ordinary world? How do the filmmakers make entering this world a significant moment?

This scene is often at a sequence climax or the Act One Climax. Sometimes there are a whole series of thresholds to be crossed.

* THRESHOLD GUARDIAN

Is there someone standing on the threshold preventing the hero/ine from entering, or someone issuing a warning?

• SEQUENCE ONE CLIMAX

In a 2-hour movie, look for this about 15 minutes in. How do the filmmakers make this moment significant? What is the change that lets you know that this sequence is over and Sequence 2 is starting?

(Each sequence in a book will have some sort of climax, as well, although the sequences are not as uniform in length and number as they tend to be in films. Look for a revelation, a location change, a big event, a setpiece.).

• PLANTS/REVEALS or SET UPS/PAYOFFS

Discussion here

• HOPE/FEAR and STAKES

(Such a big topic you just have to wait for the dedicated post.)

* PLAN

What does the hero/ine say they want to do, or what do we understand they intend to do? The plan usually starts small, with a minimum effort, and gradually we see the plan changing.

• CENTRAL QUESTION, CENTRAL STORY ACTION

Does a character state this aloud? When do we realize that this is the main question of the story?

* ACT ONE CLIMAX:

In a 2-hour movie, look for this about 30 minutes in. In a 400-page book, about 100 pages in.

How do the storytellers make this moment significant? What is the change that lets you know that this act is over and Act II is starting?

You will also possibly see these elements (these can also be in Act Two or may not be present):

***** ASSEMBLING THE TEAM

***** GATHERING THE TOOLS –

***** TRAINING SEQUENCE

And also possibly:

***** MACGUFFIN (not present in all stories but if there is one it will USUALLY be revealed in the first act).

*****TICKING CLOCK (may not have one or the other and may be revealed later in the story)

* And always - look for and IDENTIFY SETPIECES.

=====================================================

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 13.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 07, 2016 01:52

November 2, 2016

Ready, Set, Nano!!

by Alexandra Sokoloff

It's here - the big day. Big month. Big everything.

The queen of suspense, Mary Higgins Clark, said about first drafts:

Writing a first draft is like clawing my way through a mountain of concrete with my bare hands.

Isn't that the truth?

Well, the point of Nano is to write so fast that you - sometimes - forget that your hands are dripping blood. It's a stellar way of turning off your censor (we all have one of those little suckers) and just get those pages out.

I'll be posting Nano prompts throughout the month, but here's a list of helpful hints if you find yourself stuck.

1. Keep moving forward – DO NOT go back and endlessly revise your first chapters. You may end up throwing them out anyway. Just move forward. If you’re stuck on a scene, just write down vaguely what might happen in it or where it might happen as a place marker and move on to a scene you know better. The first draft can be just a sketch – the important thing is to get it all down, from beginning to end. Then you can start to layer in all the other stuff.

2. Keep the story elements checklist close at hand for easy reference.

- Story Elements Checklist for Generating Index Cards

Or if you prefer the elements in a narrative:

- Narrative Structure Cheat Sheet

3. Review the elements of the act you're stuck on.

- Elements of Act One

- Elements of Act Two, Part 1

- Elements of Act Two, Part 2

- Elements of Act Three

- What Makes A Great Climax?

- Elevate Your Ending

- Creating Character

4. As you're writing, you will find out more about your story. Write the premise again, and make sure you have identified and understand the Plan and Central Story Action.

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

- What's the Plan?

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action, part 2

5. When you’re stuck - make a list.

- Stuck? Make A List.

6. Do word lists of visual and thematic elements for your story to build your image systems. Start a collage book or online clip file of images if that appeals to you.

- Thematic Image Systems

7. Remember that the first draft is always going to suck.

- Your First Draft Is Always Going To Suck

8. You can always watch movies and do breakdowns to inspire you and break you through a block.

Good luck, everyone - and feel free to stop in and gripe!

- Alex

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 13.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

It's here - the big day. Big month. Big everything.

The queen of suspense, Mary Higgins Clark, said about first drafts:

Writing a first draft is like clawing my way through a mountain of concrete with my bare hands.

Isn't that the truth?

Well, the point of Nano is to write so fast that you - sometimes - forget that your hands are dripping blood. It's a stellar way of turning off your censor (we all have one of those little suckers) and just get those pages out.

I'll be posting Nano prompts throughout the month, but here's a list of helpful hints if you find yourself stuck.

1. Keep moving forward – DO NOT go back and endlessly revise your first chapters. You may end up throwing them out anyway. Just move forward. If you’re stuck on a scene, just write down vaguely what might happen in it or where it might happen as a place marker and move on to a scene you know better. The first draft can be just a sketch – the important thing is to get it all down, from beginning to end. Then you can start to layer in all the other stuff.

2. Keep the story elements checklist close at hand for easy reference.

- Story Elements Checklist for Generating Index Cards

Or if you prefer the elements in a narrative:

- Narrative Structure Cheat Sheet

3. Review the elements of the act you're stuck on.

- Elements of Act One

- Elements of Act Two, Part 1

- Elements of Act Two, Part 2

- Elements of Act Three

- What Makes A Great Climax?

- Elevate Your Ending

- Creating Character

4. As you're writing, you will find out more about your story. Write the premise again, and make sure you have identified and understand the Plan and Central Story Action.

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

- What's the Plan?

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action, part 2

5. When you’re stuck - make a list.

- Stuck? Make A List.

6. Do word lists of visual and thematic elements for your story to build your image systems. Start a collage book or online clip file of images if that appeals to you.

- Thematic Image Systems

7. Remember that the first draft is always going to suck.

- Your First Draft Is Always Going To Suck

8. You can always watch movies and do breakdowns to inspire you and break you through a block.

Good luck, everyone - and feel free to stop in and gripe!

- Alex

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 13.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 02, 2016 02:53

November 1, 2016

Book 4 of the Huntress/FBI Thrillers out now!

Bitter Moon , Book 4 of my Thriller Award-nominated Huntress/FBI series, is now available in print, audio and ebook (ebook just $4.99!).

A haunted FBI agent is on the trail of that most rare of killers… a female serial. His hunt for her will take him across five states, and force him to question everything he knows about evil and justice.

"Sokoloff proves that a revelatory series with great characters can burrow deep. And stay there…

- The Big Thrill

The Huntress books are definitely written to be read in order! But great news: Thomas & Mercer has put the first three books on sale on Amazon US, just $1.99 each - and Amazon Prime members can read Book 1 for free. So if you need to catch up, start with:

Huntress: Amazon US: $1.99 Blood Moon: Amazon US: $1.99 Cold Moon: Amazon US: $1.99

Scroll down for more details about Bitter Moon - but if you like your books spoiler-free, then don’t read any further.

As you might guess by the cover, Bitter Moon takes Roarke deep into the desert, following a sixteen-year-old cold case that may be the key to Cara's bloody history. It's probably the most mystical of the books, unfolding on a dual time line, with the present and past intersecting as Roarke and fourteen-year old Cara both race to stop a sadistic serial predator.

There are new characters I think you'll love as much as I do, and you'll find out much more about Cara's past. And there are new settings! The California desert is possibly my favorite place on the planet, and for this one I'll be taking you to the magical Coachella Valley and the wine country of Temecula.

------------- WARNING: SPOILERS FOR THE SERIES -----------

BITTER MOON

FBI agent Matthew Roarke has been on leave, and in seclusion, since the capture of mass killer Cara Lindstrom—the victim turned avenger who preys on predators. Torn between devotion to the law and a powerful attraction to Cara and her lethal brand of justice, Roarke has retreated from both to search his soul. But Cara’s escape from custody and a police detective’s cryptic challenge soon draw him out of exile—into the California desert and deep into Cara’s past—to probe an unsolved murder that could be the key to her long and deadly career.

Following young Cara’s trail, Roarke uncovers a horrifying attack on a schoolgirl, the shocking suicide of another, and a human monster stalking Cara’s old high school. Separated by sixteen years, crossing paths in the present and past, Roarke and fourteen-year-old Cara must race to find and stop the sadistic sexual predator before more young girls are brutalized.

"BITTER MOON accomplishes a truly remarkable feat: It is both a prequel that explores the harrowing history and psychological development of Cara Lindstrom as it unfolded 16 years ago in a town in the California desert, and a narrative that follows FBI agent Matthew Roarke as he investigates her history—and finds himself on the trail of long-ago brutal killers who were never caught." - The Big Thrill

As always, reviewers can contact me for review copies: alex@alexandrasokoloff.com

Thanks so much for reading, and Happy Fall!

- Alex

PS: Authors - of course I always post prompts for Nanowrimo throughout November on this blog. I’m Nanoing this year myself, working on Book 5 of the Huntress series for a January 2 deadline – yike! So come on along and panic with me. :)

Published on November 01, 2016 05:07

October 29, 2016

NANOWRIMO: The Plan

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Time for one more prep post before the madness of Nanowrimo begins. So today I want to review what I've come to believe is the key to any second act, and really the whole key to story structure: The PLAN. If you're going to read any of my posts before Nanowrimo, this is probably the one!

You always hear that “Drama is conflict,” but when you think about it – what the hell does that mean, practically?

It’s actually much more true, and specific, to say that drama is the constant clashing of a hero/ine’s PLAN and an antagonist’s, or several antagonists’, PLANS.

In the first act of a story, the hero/ine is introduced, and that hero/ine either has or quickly develops a DESIRE. She might have a PROBLEM that needs to be solved, or someone or something she WANTS, or a bad situation that she needs to get out of, pronto.

Her reaction to that problem or situation is to formulate a PLAN, even if that plan is vague or even completely subconscious. But somewhere in there, there is a plan, and storytelling is usually easier if you have the hero/ine or someone else (maybe you, the author) state that plan clearly, so the audience or reader knows exactly what the expectation is.

And the protagonist’s plan (and the corresponding plan of the antagonist’s) actually drives the entire action of the second act. Stating the plan tells us what the CENTRAL ACTION of the story will be. So it’s critical to set up the plan by the end of Act One, or at the very beginning of Act Two, at the latest.

Let’s look at some examples of how plans work.

I’m going to start, improbably, with the actioner 2012, even though I thought it was a pretty terrible movie overall.

Now, I’m sure in a theater this movie delivered on its primary objective, which was a rollercoaster ride as only Hollywood special effects can provide. Whether we like it or not, there is obviously a massive worldwide audience for movies that are primarily about delivering pure sensation. Story isn’t important, nor, apparently, is basic logic. As long as people keep buying enough tickets to these movies to make them profitable, it’s the business of Hollywood to keep churning them out.

But in 2012, even in that rollercoaster ride of special effects and sensations, there was a clear central PLAN for an audience to hook into, a plan that drove the story. Without that plan, 2012 really would have been nothing but a chaos of special effects.

If you’ve seen this movie (and I know some of you have … ), there is a point in the first act where a truly over-the-top Woody Harrelson as an Art Bell-like conspiracy pirate radio commentator rants to protagonist John Cusack about having a map that shows the location of “spaceships” that the government is stocking to abandon planet when the prophesied end of the world commences.

Although Cusack doesn’t believe it at the time, this is the PLANT (sort of camouflaged by the fact that Woody is a nutjob), that gives the audience the idea of what the PLAN OF ACTION will be: Cusack will have to go back for the map in the midst of all the cataclysm, then somehow get his family to these “spaceships” in order for all of them to survive the end of the world.

The PLAN is reiterated, in dialogue, when Cusack gets back to his family and tells his ex-wife basically exactly what I just said above: “We’re going to go back to the nutjob with the map so that we can get to those spaceships and get off the planet before it collapses.”

And lo and behold, that’s exactly what happens; it’s not only Cusack’s PLAN, but the central action of the story, that can be summed up as a CENTRAL QUESTION: Will Cusack be able to get his family to the spaceships before the world ends?

Or put another way, the CENTRAL STORY ACTION is John Cusack getting his family to the spaceships before the world ends.

(Note the ticking clock, there, as well. And as if the end of the world weren’t enough, the movie also starts a literal “Twenty-nine minutes to the end of the world!” ticking computer clock at, yes, 29 minutes before the end of the movie. I must point out here that ticking clocks are dangerous because of the huge cliché factor. We all need to study structure to know what not to do, as well.)

And all this happens about the end of Act I. Remember that I said that it’s essential to have laid out the CENTRAL QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION by the end of Act I? But also at this point – or possibly just after the climax of Act I, in the very beginning of Act II – we need to know what the PLAN is. PLAN and CENTRAL QUESTION are integrally related, and I keep looking for ways to talk about it because this is such an important concept to master.

A reader/audience really needs to know what the overall PLAN is, even if they only get it in a subconscious way. Otherwise they are left floundering, wondering where the hell all of this is going.

In 2012, even in the midst of all the buildings crumbling and crevasses opening and fires booming and planes crashing, we understand on some level what is going on:

- What does the protagonist want? (OUTER DESIRE) To save his family.

- How is he going to do it? (PLAN) By getting the map from the nutjob and getting his family to the secret spaceships (that aren’t really spaceships).

- What’s standing in his way? (FORCES OF OPPOSITION) About a million natural disasters as the planet caves in, an evil politician who has put a billion dollar price tag on tickets for the spaceship, a Russian Mafioso who keeps being in the same place at the same time as Cusack, and sometimes ends up helping, and sometimes ends up hurting. (Was I the only one queased out by the way all the Russian characters were killed off, leaving only the most obnoxious kids on the planet?)

Here’s another example, from a much better movie:

At the end of the first sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark (which is arguably two sequences in itself, first the action sequence in the cave in South America, then the university sequence back in the US), Indy has just finished teaching his archeology class when his mentor, Marcus, comes to meet him with a couple of government agents who have a job for him (CALL TO ADVENTURE). The agents explain that Hitler has become obsessed with collecting occult artifacts from all over the world, and is currently trying to find the legendary Lost Ark of the Covenant, which is rumored to make any army in possession of it invincible in battle.

So there’s the MACGUFFIN, the object that everyone wants, and the STAKES: if Hitler’s minions (THE ANTAGONISTS) get this Ark before Indy does, the Nazi army will be invincible.

And then Indy explains his PLAN to find the Ark: his old mentor, Abner Ravenwood, was an expert on the Ark and had an ancient Egyptian medallion on which was inscribed the instructions for using the medallion to find the hidden location of the Ark.

So after hearing the plan, we understand the entire OVERALL ACTION of the story: Indy is going to find Abner (his mentor) to get the medallion, then use the medallion to find the Ark before Hitler’s minions can get it.

And even though there are lots of twists along the way, that’s really it: the basic action of the story.

Generally, PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are really the same thing – the Central Action of the story is carrying out the specific Plan. And the CENTRAL QUESTION of the story can be generally stated as – “Will the Plan succeed?”

Again, the PLAN, CENTRAL QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are almost always set up – and spelled out – by the end of the first act, although the specifics of the Plan may be spelled out right after the Act I Climax at the very beginning of Act II.

Can it be later? Well, anything’s possible, but the sooner a reader or audience understands the overall thrust of the story action, the sooner they can relax and let the story take them where it’s going to go. So much of storytelling is about you, the author, reassuring your reader or audience that you know what you’re doing, so they can sit back and let you drive.

Try taking a favorite movie or book (or two or three) and identifying the PLAN, CENTRAL STORY ACTION and CENTRAL QUESTION of them in a few sentences. Like this:

- In Inception, the PLAN is for the team of dream burglars to go into a corporate heir’s dreams to plant the idea of breaking up his father’s corporation. (So the CENTRAL ACTION is going into the corporate heir’s dream and planting the idea, and the CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will they succeed?)

- In Sense and Sensibility, the PLAN is for Marianne and Elinor to secure the family’s fortune and their own happiness by marrying well. (How are they going to do that? By the period’s equivalent of dating – which is the CENTRAL ACTION. Yes, dating is a PLAN! The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will the sisters succeed in marrying well?)

- In The Proposal, Margaret’s PLAN is to learn enough about Andrew over the four-day weekend with his family to pass the INS marriage test so she won’t be deported. (The CENTRAL ACTION is going to Alaska to meet Andrew’s family and pretending to be married while they learn enough about each other to pass the test. The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will they be able to successfully fake the marriage?

Now, try it with your own story!

- What does the protagonist WANT?

- How does s/he PLAN to do it?

- What and who is standing in his or her way?

For example, in my spooky thriller, Book of Shadows , here's the Act One set up: the protagonist, homicide detective Adam Garrett, is called on to investigate the murder of a college girl, which looks like a Satanic killing. Garrett and his partner make a quick arrest of a classmate of the girl's, a troubled Goth musician. But Garrett is not convinced of the boy's guilt, and when a practicing witch from nearby Salem insists the boy is innocent and there have been other murders, he is compelled to investigate further.

So Garrett’s PLAN and the CENTRAL ACTION of the story is to use the witch and her specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate the murder on his own, all the while knowing that she is using him for her own purposes and may well be involved in the killing. The CENTRAL QUESTION is: will they catch the killer before s/he kills again – and/or kills Garrett (if the witch turns out to be the killer)?

- What does the protagonist WANT? To catch the killer before s/he kills again.

- How does he PLAN to do it? By using the witch and her specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate further.

- What’s standing in his way? His own department, the killer, and possibly the witch herself. And if the witch is right … possibly even a demon.

It’s important to note that the Plan and Central Action of the story are not always driven by the protagonist. Usually, yes. But in The Matrix, it’s Neo’s mentor Morpheus who has the overall PLAN, which drives the central action right up until the end of the second act. The Plan is to recruit and train Neo, whom Morpheus believes is “The One” prophesied to destroy the Matrix. So that’s the action we see unfolding: Morpheus recruiting, deprogramming and training Neo, who is admittedly very cute, but essentially just following Morpheus’s orders for two thirds of the movie.

Does this weaken the structure of that film? Not at all. Morpheus drives the action until that crucial point, the Act Two Climax, when he is abducted by the agents of the Matrix, at which point Neo steps into his greatness and becomes “The One” by taking over the action and making a new plan: to rescue Morpheus by sacrificing himself.

It is a terrific way to show a huge character arc: Neo stepping into his destiny. And I would add that this is a common structural pattern for mythic journey stories – in Lord of the Rings, it's Gandalf who has the PLAN and drives the reluctant Frodo in the central story action until Frodo finally takes over the action himself.

Here’s another example. In the very funny romantic comedy It’s Complicated, Meryl Streep’s character Jane is the protagonist, but she doesn’t drive the action or have any particular plan of her own. It’s her ex-husband Jake (Alec Baldwin), who seduces her and at the end of the first act, proposes (in an extremely persuasive speech) that they continue this affair as a perfect solution to both their love troubles – it will fulfill their sexual and intimacy needs without disrupting the rest of their lives.