Alexandra Sokoloff's Blog, page 12

June 20, 2017

Junowrimo: Act II, Part Two

by Alexandra Sokoloff

While I am moving on to prompts for the second half of Act Two, remember that wherever you are in this process is just fine. Personally I think it would be a little crazy to be into the second half of the second act in just three weeks!

So if you're not this far, just save this post for later.

If you're new to this blog, start here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

A few general things about Act II, Part 2. This is almost always the darkest quarter of the story. While in Act II, Part 1, the hero/ine is generally (but not always) winning, after the Midpoint, the hero/ine starts to lose, and lose big. And also lose very fast. In fact, this is the quarter that is most often shortened if you are writing a shorter book or movie, because it's not all that hard and doesn't take all that much time to pull the rug out from your protagonist.

Just knowing that basic, very general distinction between the two halves of Act Two can be very, very useful.

But getting more specific...

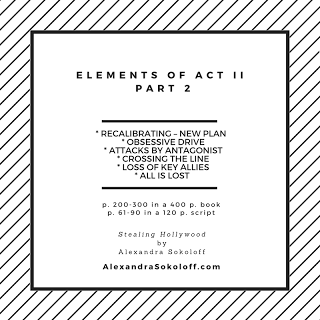

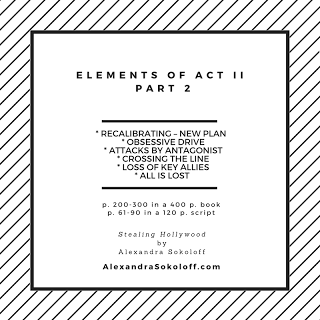

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

(More on MIDPOINT).

Act II, Part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud.

How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

More discussion on Elements Of Act II:2

Happy Solstice!!

- Alex

=====================================================

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $12.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

While I am moving on to prompts for the second half of Act Two, remember that wherever you are in this process is just fine. Personally I think it would be a little crazy to be into the second half of the second act in just three weeks!

So if you're not this far, just save this post for later.

If you're new to this blog, start here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

A few general things about Act II, Part 2. This is almost always the darkest quarter of the story. While in Act II, Part 1, the hero/ine is generally (but not always) winning, after the Midpoint, the hero/ine starts to lose, and lose big. And also lose very fast. In fact, this is the quarter that is most often shortened if you are writing a shorter book or movie, because it's not all that hard and doesn't take all that much time to pull the rug out from your protagonist.

Just knowing that basic, very general distinction between the two halves of Act Two can be very, very useful.

But getting more specific...

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

(More on MIDPOINT).

Act II, Part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud.

How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

More discussion on Elements Of Act II:2

Happy Solstice!!

- Alex

=====================================================

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $12.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on June 20, 2017 07:20

June 16, 2017

JUNOWRIMO: Midpoint

It's a little past the midpoint of the month, so some, not all, of you will be coming up on the midpoint of your books. I am as ever skeptical that you can really get to the midpoint of a book in two weeks... but it's still a good reason to talk about one of the most important elements of any book, film, TV show, or play.

If you're new to this blog, start here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

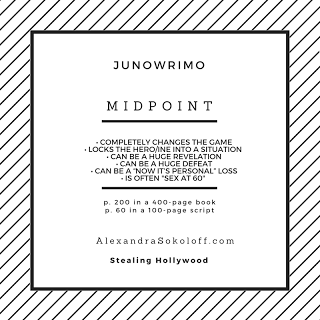

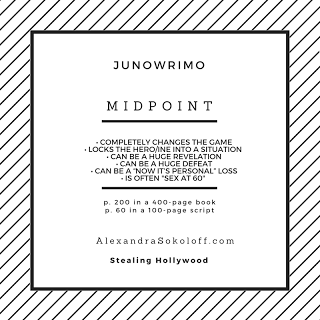

THE MIDPOINT

All of the first half of the second act – that’s p. 30-60 in a script, p. 100 to p. 200 in a 400-page book, is leading up to the MIDPOINT. So the Midpoint occurs at about one hour into a movie, and at about page 200 in a book.

The Midpoint is also often called the MOMENT OF COMMITMENT or the POINT OF NO RETURN or NO TURNING BACK: the hero/ine commits irrevocably to the action.

The Midpoint is one of the most important scenes or sequences in any book or film: a major shift in the dynamics of the story. Something huge will be revealed; something goes disastrously wrong; someone close to the hero/ine dies, intensifying her or his commitment (What I call the “Now it’s personal” scene… imagine Clint Eastwood or Bruce Willis growling the line). Often the whole emotional dynamic between characters changes with what Hollywood calls, “Sex at Sixty” (that’s 60 minutes, not sixty years!).

Often a TICKING CLOCK is introduced at the Midpoint, as we will discuss further in the chapter on Creating Suspense (Chapter 31). A clock is a great way to speed up the action and increase the urgency of your story.

The Midpoint can also be a huge defeat, which requires a recalculation and NEW PLAN of attack. It’s a game-changer, and it locks the hero/ine even more inevitably into the story.

Let's look at some examples.

As I've said before, a favorite PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION of mine is in Brian DePalma’s The Untouchables.

Young FBI agent Eliot Ness is assigned to bring down mobster Al Capone. So far no one in law enforcement or government has been able to pin Capone to any of his heinous crimes; he keeps too much distance between himself and the actual killings, hijackings, extortions, etc. One of Ness’ Untouchable team, a FBI accountant, proposes that the team gather evidence and nail Capone on federal tax evasion. It’s not sexy, but the penalty is up to 25 years in prison. (As you might know, this PLAN is historically accurate: Al Capone was actually finally charged and imprisoned on the charge of tax evasion.)

So the PLAN and CENTRAL ACTION of the story becomes to locate one of Capone’s bookkeepers, take him into custody and force him to testify against Capone. Which they do. (With plenty of action sequences, of course.)

So as we approach the MIDPOINT, Ness’s team has the bookkeeper in custody, the trial is set, and Ness’s men are escorting the bookkeeper to court.

But the movie is only half over. So of course, as very often happens at the midpoint, the plan fails. In a suspenseful and emotional wrenching MIDPOINT CLIMAX, Ness’s accountant teammate, whom we have come to love, escorts the bookkeeper into the courthouse elevator to take him up to the courtroom. As the doors close, we see the police guard is actually one of Capone’s men.

Ness and his other teammate (a criminally hot Andy Garcia), realize that something’s wrong and race up (down?) the stairs to catch the elevator, but arrive to find a bloodbath – both accountants brutally murdered, and the word TOUCHABLE painted on the elevator in blood.

So the plan is totally foiled – they have no witness and no more case. It’s a great midpoint reversal, because we – and Ness himself – have no idea what the team is going to be able to do next (and also Ness is so emotionally devastated by the loss of his teammate that he begins to do reckless things.).

Not only does the murder of the two accountants (Capone's and Ness's) completely annihilate Ness's PLAN), but the murder of Ness's teammate makes the stakes deeply personal.

But a Midpoint doesn’t have to be a huge action scene. Another interesting and tonally very different Midpoint happens in Raiders of the Lost Ark. I’m sure some people would dispute me on this one (and people argue about the exact midpoint of movies all the time), but I would say the Midpoint is the scene that occurs exactly 60 minutes into the film, in which, having determined that the Nazis are digging in the wrong place in the archeological site, Indy goes down into that chamber with the pendant and a staff of the proper height, and uses the crystal in the pendant to pinpoint the exact location of the Ark.

This scene is quiet, and involves only one person, but it’s mystically powerful – note the use of light and the religious quality of the music… and Indy is decked out in robes almost like, well, Moses. Staff and all. Indy stands like God over the miniature of the temple city, and the beam of light comes through the crystal like light from heaven. It’s all a foreshadowing of the final climax, in which God intervenes in much the same way. Very effective, with lots of subliminal manipulation going on. And of course, at the end of the scene, Indy has the information he needs to retrieve the Ark. I would also point out that the Midpoint is often some kind of mirror image of the final climax; it’s an interesting device to use, and you may find yourself using it without even being aware of it.

(I will concede that in Raiders, you could call the Midpoint a two-parter: Indy’s discovery that Marion is still alive is a big twist. But personally I think that scene is part of the next sequence).

Another very different kind of midpoint occurs in Silence of the Lambs: the “Quid Pro Quo” scene between Clarice and Lecter, in which she bargains personal information to get Lecter’s insights into the case. Clarice is on a time clock, here, because Catherine Martin has been kidnapped and Clarice knows they have only three days before Buffalo Bill kills her. Clarice goes in at first to offer Lecter what she knows he desires most (because he has STATED his desire, clearly and early on) – a transfer to a Federal prison, away from Dr. Chilton and with a view. Clarice has a file with that offer from Senator Martin – she says – but in reality the offer is a total fake. We don’t know this at the time, but it has been cleverly PLANTED that it’s impossible to fool Lecter (Crawford sends Clarice in to the first interview without telling her what the real purpose is so that Lecter won’t be able to read her). But Clarice has learned and grown enough to fool Lecter – and there’s a great payoff when Lecter later acknowledges that fact.

The deal is not enough for Lecter, though – he demands that Clarice do exactly what her boss, Crawford, has warned her never to do: he wants her to swap personal information for clues – a classic deal with the devil game.

After Clarice confesses painful secrets, Lecter gives her the clue she’s been digging for – to search for Buffalo Bill through the sex reassignment clinics. And as is so often the case, there is a second climax within the midpoint – the film cuts to the killer in his basement, standing over the pit making a terrified Catherine put lotion on her skin – it’s a horrifying curtain and drives home the stakes. (Each climax in SOTL is a one-two punch - screen the movie again and see what I mean!).

I recently reread Harlan Coben's The Woods, which employs a great technique to craft an explosive Midpoint: the book has an A story and a B story (well, really, with Coben it's always about sixteen different threads of each plot intricately interwoven, but two main plots). In the B story, the protagonist is prosecuting two frat boys who raped a stripper at a frat party, and at the Midpoint is the main courtroom confrontation of that plot. The storyline continues, but now it becomes subordinate (and of course interconnected to) to the building A plot. This very emotional climaxing of the B plot at the midpoint is a terrifically effective structure technique that is great to have in your story structure toolbox.

In Sense and Sensibility, the Midpoint is the emotionally wrenching scene in which Lucy Steele reveals to Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars for five years. We are so committed to Edward and Elinor’s love that we are as devastated as Elinor is, and just as shocked that Edward would have lied to her. The Midpoint is even more wrenching because Elinor’s sister Marianne has also just been abandoned by her love interest. It’s a double-punch to the gut.

In Notting Hill, Julia Roberts has asked Hugh Grant up to her hotel suite for the first time, and Hugh walks in to find that Julia’s movie star boyfriend, Alec Baldwin, whom Hugh knew nothing about, is already there with her. We know that Hugh’s GHOST is that his ex-wife left him for a man who looked just like Harrison Ford (Alec is pretty close!), and to add to this blow, Alec mistakes Hugh for a room-service waiter and tips him, asking him to clean up while he takes Julia into the bedroom. Total emotional annihilation.

In a romance, the Midpoint is very often sexual or emotional. But the Midpoint can often be one of the most memorable visual SETPIECES of the story, just to further drive its importance home.

Note that the Midpoint is not necessarily just one scene; it can be a double punch as I just pointed out about Sense And Sensibility, and it can also be a progression of scenes and revelations that include a climactic scene, a complete change of location, a major revelation, a major reversal, a cliffhanger – all or any combination of the above.

One of the great Midpoints in theater and film is in My Fair Lady. Talk about a double punch! There is not one iconic song at the Midpoint curtain, but two: first “The Rain In Spain”, in which Eliza finally starts to speak with perfect diction, and Professor Higgins, the Colonel, and Eliza celebrate with wild and joyous dancing: a moment of triumph. Then when the housekeeper takes Eliza upstairs to bed, Higgins privately tells the Colonel that she’s ready: they can test her out in public. He intends to take her to an Embassy ball and pass her off as a lady to win his bet with the Colonel, which Eliza knows nothing about. Meanwhile upstairs, giddy with happiness, Eliza sings “I Could Have Danced All Night”, and we realize she has fallen in love with the Professor.

Not just two of the greatest songs of the musical theater in a row, but all of this SETUP, big HOPE, FEAR, and STAKES. Eliza is in love with Higgins and he’s just using her for a bet. There’s a huge TEST coming up at this ball, and we saw excitable Eliza fail miserably in her first public test at the Ascot races. There’s a penalty of prison for impersonating a lady, so there are not just the emotional stakes of a possible broken heart, but possible prison time.

Do you think anyone was not going to come back into the theater to see what happens at that ball?

Asking a big question like that is a great technique to use at the Midpoint.

A totally different, but equally famous example: in Jaws, the Midpoint climax is actually a whole sequence long: a highly suspenseful setpiece in which the city officials have refused to shut down the beaches, so Sheriff Brody is out there on the beach keeping watch (as if that’s going to prevent a shark attack!), the Coast Guard is patrolling the ocean – and, almost as if it’s aware of the whole plan, the shark swims into an unguarded harbor, where it attacks and swallows a man and for a horrifying moment we think that it has also killed Brody’s son (really it’s only frightened him into near-paralysis). It’s a huge climax and adrenaline rush, but it’s not over yet. Because now the Mayor writes the check to hire Quint to hunt down the shark, and since Brody’s family has been threatened (“Now it’s PERSONAL”), Brody decides to go out with Quint and Hooper on the boat – and there’s also a huge change in location as we see that little boat headed out to the open sea.

It really pays to start taking note of the Midpoints of films and books. If you find that your story is sagging in the middle, the first thing you should look at is your Midpoint scene.

I know this and I still sometimes forget it. When I turned in my poltergeist novel The Unseen, I knew that I was missing something in the middle, even though there was a very clear change in location and focus at the Midpoint: it’s the point at which my characters actually move into the supposedly haunted house and begin their experiment.

But there was still something missing in the scene right before, the close of the first half, and my editor had the same feeling, without really knowing what was needed, although it had something to do with the motivation of the heroine – the reason she would put herself in that kind of danger. So I looked at the scene before the characters moved in to the house, and lo and behold: what I was missing was “Sex at Sixty.” It’s my heroine’s desire for one of the other characters that makes her commit to the investigation, and I wasn’t making that desire line clear enough.

The Midpoint often LOCKS THE HERO/INE INTO A COURSE OF ACTION, or sometimes, physically locks the hero/ine into a location.

A great recent example is Inception: at the Midpoint, there’s a big action sequence, ending in a gun battle in which one of the allies, Saito (who hired the team to break into this dream) is badly wounded, and the team discovers that they can’t get out of the dream while Saito is unconscious. They’re stuck, perhaps forever, which forces them to devise a new PLAN.

There’s a not-so recent movie called Ghost Ship, about a salvage crew investigating a derelict ocean liner which has mysteriously appeared out in the middle of the Bering Straight, after being lost without a trace for forty years. At the Midpoint, the salvage crew’s own boat mysteriously catches on fire and sinks (taking one of the crew with it), forcing the entire crew to board the haunted ocean liner. They are physically locked into the situation, now, and their original PLAN – to tow the ocean liner back to shore – must change; they now have to repair the ocean liner and sail her out of the Strait. This development also solves the perennial problem of haunted house – or haunted ship – stories: “Why don’t the characters just leave?”

It’s a great Midpoint scene for all of the above reasons, plus it’s a great visual and action setpiece: the explosion of the salvage boat, the rescue (and loss) of crew members, and the suspense of who will get out of the water and on to the ocean liner alive.

So as you're writing your fingers off, try taking a minute to contemplate what your Midpoint is, and how it changes the action of your book. If you can devise a great setpiece for your midpoint and also somehow destroy your hero'ine's initial plan, you won't have to worry about a sagging middle section, because you and your hero/ine will suddenly be scrambling to figure out a brand new and exiting plan of action to get their desire.

It really is the KEY to Act II.

- Alex

=====================================================

If you'd like to to see more of these story elements in action, I strongly recommend that you watch at least one and much better, three of the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

I do full breakdowns of The Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone, Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

If you're new to this blog, start here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

THE MIDPOINT

All of the first half of the second act – that’s p. 30-60 in a script, p. 100 to p. 200 in a 400-page book, is leading up to the MIDPOINT. So the Midpoint occurs at about one hour into a movie, and at about page 200 in a book.

The Midpoint is also often called the MOMENT OF COMMITMENT or the POINT OF NO RETURN or NO TURNING BACK: the hero/ine commits irrevocably to the action.

The Midpoint is one of the most important scenes or sequences in any book or film: a major shift in the dynamics of the story. Something huge will be revealed; something goes disastrously wrong; someone close to the hero/ine dies, intensifying her or his commitment (What I call the “Now it’s personal” scene… imagine Clint Eastwood or Bruce Willis growling the line). Often the whole emotional dynamic between characters changes with what Hollywood calls, “Sex at Sixty” (that’s 60 minutes, not sixty years!).

Often a TICKING CLOCK is introduced at the Midpoint, as we will discuss further in the chapter on Creating Suspense (Chapter 31). A clock is a great way to speed up the action and increase the urgency of your story.

The Midpoint can also be a huge defeat, which requires a recalculation and NEW PLAN of attack. It’s a game-changer, and it locks the hero/ine even more inevitably into the story.

Let's look at some examples.

As I've said before, a favorite PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION of mine is in Brian DePalma’s The Untouchables.

Young FBI agent Eliot Ness is assigned to bring down mobster Al Capone. So far no one in law enforcement or government has been able to pin Capone to any of his heinous crimes; he keeps too much distance between himself and the actual killings, hijackings, extortions, etc. One of Ness’ Untouchable team, a FBI accountant, proposes that the team gather evidence and nail Capone on federal tax evasion. It’s not sexy, but the penalty is up to 25 years in prison. (As you might know, this PLAN is historically accurate: Al Capone was actually finally charged and imprisoned on the charge of tax evasion.)

So the PLAN and CENTRAL ACTION of the story becomes to locate one of Capone’s bookkeepers, take him into custody and force him to testify against Capone. Which they do. (With plenty of action sequences, of course.)

So as we approach the MIDPOINT, Ness’s team has the bookkeeper in custody, the trial is set, and Ness’s men are escorting the bookkeeper to court.

But the movie is only half over. So of course, as very often happens at the midpoint, the plan fails. In a suspenseful and emotional wrenching MIDPOINT CLIMAX, Ness’s accountant teammate, whom we have come to love, escorts the bookkeeper into the courthouse elevator to take him up to the courtroom. As the doors close, we see the police guard is actually one of Capone’s men.

Ness and his other teammate (a criminally hot Andy Garcia), realize that something’s wrong and race up (down?) the stairs to catch the elevator, but arrive to find a bloodbath – both accountants brutally murdered, and the word TOUCHABLE painted on the elevator in blood.

So the plan is totally foiled – they have no witness and no more case. It’s a great midpoint reversal, because we – and Ness himself – have no idea what the team is going to be able to do next (and also Ness is so emotionally devastated by the loss of his teammate that he begins to do reckless things.).

Not only does the murder of the two accountants (Capone's and Ness's) completely annihilate Ness's PLAN), but the murder of Ness's teammate makes the stakes deeply personal.

But a Midpoint doesn’t have to be a huge action scene. Another interesting and tonally very different Midpoint happens in Raiders of the Lost Ark. I’m sure some people would dispute me on this one (and people argue about the exact midpoint of movies all the time), but I would say the Midpoint is the scene that occurs exactly 60 minutes into the film, in which, having determined that the Nazis are digging in the wrong place in the archeological site, Indy goes down into that chamber with the pendant and a staff of the proper height, and uses the crystal in the pendant to pinpoint the exact location of the Ark.

This scene is quiet, and involves only one person, but it’s mystically powerful – note the use of light and the religious quality of the music… and Indy is decked out in robes almost like, well, Moses. Staff and all. Indy stands like God over the miniature of the temple city, and the beam of light comes through the crystal like light from heaven. It’s all a foreshadowing of the final climax, in which God intervenes in much the same way. Very effective, with lots of subliminal manipulation going on. And of course, at the end of the scene, Indy has the information he needs to retrieve the Ark. I would also point out that the Midpoint is often some kind of mirror image of the final climax; it’s an interesting device to use, and you may find yourself using it without even being aware of it.

(I will concede that in Raiders, you could call the Midpoint a two-parter: Indy’s discovery that Marion is still alive is a big twist. But personally I think that scene is part of the next sequence).

Another very different kind of midpoint occurs in Silence of the Lambs: the “Quid Pro Quo” scene between Clarice and Lecter, in which she bargains personal information to get Lecter’s insights into the case. Clarice is on a time clock, here, because Catherine Martin has been kidnapped and Clarice knows they have only three days before Buffalo Bill kills her. Clarice goes in at first to offer Lecter what she knows he desires most (because he has STATED his desire, clearly and early on) – a transfer to a Federal prison, away from Dr. Chilton and with a view. Clarice has a file with that offer from Senator Martin – she says – but in reality the offer is a total fake. We don’t know this at the time, but it has been cleverly PLANTED that it’s impossible to fool Lecter (Crawford sends Clarice in to the first interview without telling her what the real purpose is so that Lecter won’t be able to read her). But Clarice has learned and grown enough to fool Lecter – and there’s a great payoff when Lecter later acknowledges that fact.

The deal is not enough for Lecter, though – he demands that Clarice do exactly what her boss, Crawford, has warned her never to do: he wants her to swap personal information for clues – a classic deal with the devil game.

After Clarice confesses painful secrets, Lecter gives her the clue she’s been digging for – to search for Buffalo Bill through the sex reassignment clinics. And as is so often the case, there is a second climax within the midpoint – the film cuts to the killer in his basement, standing over the pit making a terrified Catherine put lotion on her skin – it’s a horrifying curtain and drives home the stakes. (Each climax in SOTL is a one-two punch - screen the movie again and see what I mean!).

I recently reread Harlan Coben's The Woods, which employs a great technique to craft an explosive Midpoint: the book has an A story and a B story (well, really, with Coben it's always about sixteen different threads of each plot intricately interwoven, but two main plots). In the B story, the protagonist is prosecuting two frat boys who raped a stripper at a frat party, and at the Midpoint is the main courtroom confrontation of that plot. The storyline continues, but now it becomes subordinate (and of course interconnected to) to the building A plot. This very emotional climaxing of the B plot at the midpoint is a terrifically effective structure technique that is great to have in your story structure toolbox.

In Sense and Sensibility, the Midpoint is the emotionally wrenching scene in which Lucy Steele reveals to Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars for five years. We are so committed to Edward and Elinor’s love that we are as devastated as Elinor is, and just as shocked that Edward would have lied to her. The Midpoint is even more wrenching because Elinor’s sister Marianne has also just been abandoned by her love interest. It’s a double-punch to the gut.

In Notting Hill, Julia Roberts has asked Hugh Grant up to her hotel suite for the first time, and Hugh walks in to find that Julia’s movie star boyfriend, Alec Baldwin, whom Hugh knew nothing about, is already there with her. We know that Hugh’s GHOST is that his ex-wife left him for a man who looked just like Harrison Ford (Alec is pretty close!), and to add to this blow, Alec mistakes Hugh for a room-service waiter and tips him, asking him to clean up while he takes Julia into the bedroom. Total emotional annihilation.

In a romance, the Midpoint is very often sexual or emotional. But the Midpoint can often be one of the most memorable visual SETPIECES of the story, just to further drive its importance home.

Note that the Midpoint is not necessarily just one scene; it can be a double punch as I just pointed out about Sense And Sensibility, and it can also be a progression of scenes and revelations that include a climactic scene, a complete change of location, a major revelation, a major reversal, a cliffhanger – all or any combination of the above.

One of the great Midpoints in theater and film is in My Fair Lady. Talk about a double punch! There is not one iconic song at the Midpoint curtain, but two: first “The Rain In Spain”, in which Eliza finally starts to speak with perfect diction, and Professor Higgins, the Colonel, and Eliza celebrate with wild and joyous dancing: a moment of triumph. Then when the housekeeper takes Eliza upstairs to bed, Higgins privately tells the Colonel that she’s ready: they can test her out in public. He intends to take her to an Embassy ball and pass her off as a lady to win his bet with the Colonel, which Eliza knows nothing about. Meanwhile upstairs, giddy with happiness, Eliza sings “I Could Have Danced All Night”, and we realize she has fallen in love with the Professor.

Not just two of the greatest songs of the musical theater in a row, but all of this SETUP, big HOPE, FEAR, and STAKES. Eliza is in love with Higgins and he’s just using her for a bet. There’s a huge TEST coming up at this ball, and we saw excitable Eliza fail miserably in her first public test at the Ascot races. There’s a penalty of prison for impersonating a lady, so there are not just the emotional stakes of a possible broken heart, but possible prison time.

Do you think anyone was not going to come back into the theater to see what happens at that ball?

Asking a big question like that is a great technique to use at the Midpoint.

A totally different, but equally famous example: in Jaws, the Midpoint climax is actually a whole sequence long: a highly suspenseful setpiece in which the city officials have refused to shut down the beaches, so Sheriff Brody is out there on the beach keeping watch (as if that’s going to prevent a shark attack!), the Coast Guard is patrolling the ocean – and, almost as if it’s aware of the whole plan, the shark swims into an unguarded harbor, where it attacks and swallows a man and for a horrifying moment we think that it has also killed Brody’s son (really it’s only frightened him into near-paralysis). It’s a huge climax and adrenaline rush, but it’s not over yet. Because now the Mayor writes the check to hire Quint to hunt down the shark, and since Brody’s family has been threatened (“Now it’s PERSONAL”), Brody decides to go out with Quint and Hooper on the boat – and there’s also a huge change in location as we see that little boat headed out to the open sea.

It really pays to start taking note of the Midpoints of films and books. If you find that your story is sagging in the middle, the first thing you should look at is your Midpoint scene.

I know this and I still sometimes forget it. When I turned in my poltergeist novel The Unseen, I knew that I was missing something in the middle, even though there was a very clear change in location and focus at the Midpoint: it’s the point at which my characters actually move into the supposedly haunted house and begin their experiment.

But there was still something missing in the scene right before, the close of the first half, and my editor had the same feeling, without really knowing what was needed, although it had something to do with the motivation of the heroine – the reason she would put herself in that kind of danger. So I looked at the scene before the characters moved in to the house, and lo and behold: what I was missing was “Sex at Sixty.” It’s my heroine’s desire for one of the other characters that makes her commit to the investigation, and I wasn’t making that desire line clear enough.

The Midpoint often LOCKS THE HERO/INE INTO A COURSE OF ACTION, or sometimes, physically locks the hero/ine into a location.

A great recent example is Inception: at the Midpoint, there’s a big action sequence, ending in a gun battle in which one of the allies, Saito (who hired the team to break into this dream) is badly wounded, and the team discovers that they can’t get out of the dream while Saito is unconscious. They’re stuck, perhaps forever, which forces them to devise a new PLAN.

There’s a not-so recent movie called Ghost Ship, about a salvage crew investigating a derelict ocean liner which has mysteriously appeared out in the middle of the Bering Straight, after being lost without a trace for forty years. At the Midpoint, the salvage crew’s own boat mysteriously catches on fire and sinks (taking one of the crew with it), forcing the entire crew to board the haunted ocean liner. They are physically locked into the situation, now, and their original PLAN – to tow the ocean liner back to shore – must change; they now have to repair the ocean liner and sail her out of the Strait. This development also solves the perennial problem of haunted house – or haunted ship – stories: “Why don’t the characters just leave?”

It’s a great Midpoint scene for all of the above reasons, plus it’s a great visual and action setpiece: the explosion of the salvage boat, the rescue (and loss) of crew members, and the suspense of who will get out of the water and on to the ocean liner alive.

So as you're writing your fingers off, try taking a minute to contemplate what your Midpoint is, and how it changes the action of your book. If you can devise a great setpiece for your midpoint and also somehow destroy your hero'ine's initial plan, you won't have to worry about a sagging middle section, because you and your hero/ine will suddenly be scrambling to figure out a brand new and exiting plan of action to get their desire.

It really is the KEY to Act II.

- Alex

=====================================================

If you'd like to to see more of these story elements in action, I strongly recommend that you watch at least one and much better, three of the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

I do full breakdowns of The Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone, Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on June 16, 2017 10:47

June 13, 2017

Junowrimo: Key Elements of Act II, Part 1

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Act Two is summed up by the greats such as, like, you know, Aristotle — as “Rising Tension” or “Progressive Complications.” Or in the classic screenwriting formula: Act One is “Get the Hero Up a Tree,” and Act Two is “Throw Rocks at Him.” (And for the impatient out there, I’ll reveal that Act Three is “Get Him Down.”)

All true enough, but a tad vague for my taste.

Here’s the thing. The first half of Act Two, which we will call Act II, Part 1 (30-60 minutes in a film, pages 100-200 in a book), is the most variable of all the acts. I can give you very specific story elements, even give them to you in a relative order, for every other part of a story, but Act II:1 can be maddening. That is, I think, because what happens in Act II:1 is totally dependent on what KIND of story you’re telling. Is it a mystery, a fairy tale, a reluctant witness story, a mistaken identity story, a mythic journey, an epic, a forbidden love story, a Chosen One story, a magical day story, several of the above, or something else entirely?

Each one of those story types has its own particular structure and story elements besides the general key story structure elements we’ve been talking about, and Act II:1 is where you most often see those specific story elements come into play.

Here are the general story elements that you will usually find in Act II, Part 1, no matter what genre or story pattern you’re working with.

The beginning of the second act of a book or film (30 minutes or 30 script pages into a film, 100 or so pages into a book) — can often be summed up as INTO THE SPECIAL WORLD or CROSSING THE THRESHOLD.

We’ve met the hero/ine in their ORDINARY WORLD, and we know something’s missing for them, even if they’re not quite sure what, themselves. They’ve received a CALL TO ADVENTURE, and may have resisted it. But now it’s time for them to leave their comfort zone and go off into the SPECIAL WORLD to go after their heart’s desire.

This step might come in the first act, or once in a while somewhat later in the second act, but it’s generally the end or beginning of a sequence: landing in Alaska in The Proposal; flying down to Cartagena in Romancing the Stone; flying to Rio in Notorious; landing in wintry New Ulm in New in Town. As you can see from those examples, it’s often the beginning of an actual, physical journey, but the Special World can be much closer to home than that. In Meet the Parents it’s the in-laws’ house; in While You Were Sleeping it’s the warm, noisy, rambling Callaghan house; in Four Weddings and a Funeral it’s a wedding (really, a whole season of weddings!). Entering the Special World is a huge moment and deserves special weight.

Dorothy opening the door of her black and white house and stepping into Technicolor Oz is one of the most famous and graphic filmic examples … Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole is a famous literary example. The passageway to the special world might be particularly unique, like the wardrobe in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe; that between-the-numbers subway platform in the Harry Potter series; Alice again, going Through the Looking Glass; the cyclone in The Wizard of Oz; the blue pill (or was it the red pill?) in The Matrix; the tesseract in A Wrinkle in Time; the umbrella Mary Poppins uses to travel with (and indeed, you can just study the Mary Poppins books for all kinds of great examples of passageways between worlds). You may not be writing a fantasy, but it’s still useful to look at more colorful examples of the INTO THE SPECIAL WORLD moment to inspire you to capture that feeling of an adventure beginning, even in a much more realistic story.

There is often a character who serves the archetypal function of a THRESHOLD GUARDIAN or GUARDIAN AT THE GATE, who gives the hero/ine trouble or a warning at this moment of entry; it’s a much-used but often powerfully effective suspense technique that always gets the pulse racing just a little faster, which is pretty much the point of suspense. At the very least a guardian at the gate will give the hero/ine conflict in a scene.

(While we’re on the subject, I highly recommend (again) Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey and John Truby’s Anatomy of Story for brilliant in-depth discussions on archetypal characters such as the Herald, Mentor, Shapeshifter, Threshold Guardian, and Trickster/Fool.)

If this has not already happened in Act One, the very early in the second act, the Hero/ine must formulate and state the PLAN. To review: we know the hero/ine’s GOAL or OUTER DESIRE by now (or if we don’t, we need to hear it, specifically). And now we need to know how the hero/ine intends to go about getting that goal. It needs to be spelled out in no uncertain terms. “Dorothy’s PLAN is to journey to the Emerald City to ask the mysterious Wizard of Oz to send her home to Kansas.” “Margaret and Andrew’s PLAN is to pretend they’re married and learn everything they can about each other during the weekend with Andrew’s family so they can pass the INS marriage test on Monday.” “Anna’s PLAN is to pay Declan to get her across Ireland to Dublin in time for her to propose to her boyfriend on Leap Day.”

Notice in the above examples that when I spell out the PLAN, I am also summing up the CENTRAL ACTION of each story: journey to Oz, pretend to be married, get across Ireland. This is so key to storytelling I wish I could somehow physically implant it in the brain of everyone who reads this book. Writers so often have no idea what the Central Action of their story is, or the Plan, and it’s the lack of these two things that is almost always where a story falls flat.

As we’ve already discussed, it’s human nature to expend the least amount of energy to get what we want. So the hero/ine’s Plan will change, constantly — as s/he first takes the absolute minimal steps to achieve her or his goal, and that minimal effort inevitably fails. So then, often reluctantly, the hero/ine has to ESCALATE (or CHANGE) THE PLAN.

Also throughout the second act, the antagonist has his or her own goal and plan, which is in direct conflict or competition with the hero/ine’s goal. We may actually see the forces of evil plotting their plots (John Grisham does this brilliantly in The Firm), or we may only see the effect of the antagonist’s plot in the continual thwarting of the hero/ine’s plans. Both techniques are effective.

This continual opposition of the protagonist’s and antagonist’s plans is the main underlying structure of the second act.

(I’m giving that its own, bold line to make sure it sinks in.)

The hero/ine’s plans should almost always be stated (although something might be held back even from the reader/audience, as in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca — that Bogey was a sly one). The antagonist’s plans might be clearly stated or kept hidden — but the effect of his/her/their plotting should be evident. It’s good storytelling if we, the reader or audience, are able to look back on the story at the end and understand how the hero/ine’s failures were a direct result of the antagonist’s scheming.

Another important storytelling and suspense technique (and I mean suspense as it plays out in any genre, not just thrillers) is KEEPING THE HERO/INE AND ANTAGONIST IN CLOSE PROXIMITY. Think of it as a chess game: the players are in a very small, confined space, and always passing within inches of each other, whether or not they’re aware of it. They should cross paths often, even if it’s not until the end until the hero/ine and the audience understand that the antagonist has been there in the shadows all along. In Romancing the Stone, a romantic comedy/adventure, you see protagonist Joan Wilder, and villain Zolo, and comic villains Ralph and Ira, all passing within spitting distance of each other, constantly. It’s a great suspense technique in itself. In While You Were Sleeping, Lucy is always running into her apparent antagonist, Peter’s brother Jack, at the hospital, as both of them are constantly visiting Peter.

Act II:1 is also where you really need to deliver on THE PROMISE OF THE PREMISE. That is, if you’re writing a fantasy, you need to give us scenes that give us the experience of wonder and magic. If you’re writing a comedy, you better be making us laugh. If you’re writing any kind of romance, here’s where we want to see and feel the hero and heroine falling in love, even if from the outside it looks more like the two of them are trying to kill each other. Think of the EXPERIENCE you want your reader or audience to have, and make sure you’re creating that experience; it’s one of your primary jobs as a writer.

The hero/ine’s ALLIES will be introduced in the second act, if they haven’t already been introduced in Act I. One of the great pleasures of Act II, Part 1 is experiencing the BONDING between the hero/ine and the allies, the team, the mentor or the love interest — or all of the above.

In fact, there is often an entire sequence you could call ASSEMBLING THE TEAM which comes early in the second act. The hero/ine has a task and needs a group of specialists to get it done. Action movies, spy movies and caper movies very often have this step and it often lasts a whole sequence. Think of Armageddon, The Sting, Mission Impossible (I mean the great TV series, of course), The Dirty Dozen, Star Wars. But you also see the team being assembled in fantasies like The Wizard of Oz and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Lord of the Rings. One of the delights of a sequence like this is that you see a bunch of highly skilled pros in top form — or alternately, a bunch of unlikely amateurs, losers that you root for because they’re so perfectly pathetic. I had fun with this in The Harrowing; even if you’re not writing an action or caper story, which I definitely wasn’t in that book, if you’ve got an ensemble cast of characters, the techniques of an Assembling the Team sequence can be hugely helpful. The inevitable clash of personalities, the constant divaness and one-upmanship, and the reluctant bonding, make for some great scenes; it’s a lively and compelling storytelling technique that you can see at its best in Four Weddings and a Funeral (in fact almost all of the films of Richard Curtis have stellar ensembles).

There is also often a TRAINING SEQUENCE in the first half of the second act. In a mentor movie, this is a pretty obligatory sequence. Think of Karate Kid, and that priceless Meeting the Mentor/Training sequence that introduces Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back.

There’s often a SERIES OF TESTS designed by the mentor (look at An Officer and a Gentleman and Silence of the Lambs). It could be the antagonist who is putting the heroine through tests (there’s a great sequence of this in While You Were Sleeping). And when there is no mentor, it may be life itself that seems to be designing the tests and challenges (well, and doesn’t life do exactly that?). Look at how Fate slyly intervenes in Groundhog Day, and in a more subtle way, in French Kiss.

Another inevitable element of the training sequence, and common to Act II:1 in general, is PLANTS AND PAYOFFS. For example, we learn that the hero/ine (and/or other members of the team) has a certain weakness in battle. That weakness will naturally have to be tested in the final battle. Yoda continually gets angry with Luke for not trusting the Force … so in his final battle with Vader, Luke’s only chance of survival is putting his entire fate in the hands of the Force he’s not sure he believes in. It’s a lovely moment of spiritual transcendence.

Very often in the second act we will see a battle before the final battle in which the hero/ine fails because of this weakness, so the suspense is even greater when s/he goes into the final battle in the third act. An absolutely beautiful example of this is in Dirty Dancing. In rehearsal after rehearsal, Baby can never, ever keep her balance in that flashy dance lift. She and Johnny attempt the lift in an early dance performance, Baby chickens out, and they cover the flub in an endearingly comic way. But in that final performance number she nails the lift, and it’s a great moment for her as a character and for the audience, quite literally uplifting.

Of course you’ll want to weave Plants and Payoffs all through the story. You can often develop these in rewrites, and it’s a good idea to do one read-through just looking for places to plant and payoff. One of the most classic examples of a plant is Indy freaking out about the snake on the plane in the first few minutes of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The plant is cleverly hidden because we think it’s just a comic moment: this big, bad hero just survived a maze of lethal booby traps and an entire tribe of warriors trying to kill him, and then he wimps out about a little old snake. But the real payoff comes way later when Sallah slides the stone slab off the entrance to the tomb and Indy shines the light down into the pit — to reveal a live mass of thousands of coiling snakes. It’s so much later in the film that we’ve completely forgotten that Indy has a pathological fear of snakes — but that’s what makes it all so funny. (Of course, it’s also a suspense builder in this case: the descent into the tomb is that much more scary because we’re feeling Indy’s revulsion.)

I very strongly encourage novelists to start watching movies for Plants and Payoffs (and I’ve included a whole section on the technique, Chapter 32). Other names for this technique are Setup/Reveal or simply FORESHADOWING (which can be a bit different, more subtle). Woody Allen’s film, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, does this beautifully with the long buildup to the entrance of Maria Elena, the Penelope Cruz character. Penelope completely delivers on her introduction and I knew she was a shoo-in for an Oscar nomination for that one. (In fact, she won.)

The Training Sequence can also involve a “Gathering the Tools” or “Gadget” Sequence. The wild gadgets and makeup were a huge part of the appeal of Mission Impossible (original TV series) and spoofed to hysterical success in Get Smart (original TV series), and these days, CSI uses the same technique to massive popular effect.

In a love story or romantic comedy, the Training Sequence or Tools Sequence is often a Shopping Sequence or a Workout Sequence or a Makeover Sequence, or a combination of all of the above. The heroine, with the help of a mentor or ally, undergoes a transformation through acquiring the most important of tools: the right clothes and shoes and hairstyle. It’s worked since Cinderella, whose personal shopper/fairy godmother considerately made house calls. See the original Arthur for the world’s loveliest example — can I have John Gielgud for my fairy godmother, please? But there are practically infinite examples: Miss Congeniality, Clueless, Maid to Order, My Fair Lady, New in Town, The Princess Diaries — we love this scene. Use it!

And the fairy tale version of Gathering the Tools is a really useful structure to look at. Remember all those tales in which the hero or heroine was innocently kind to horrible old hags or helpless animals (or even apple trees), and those creatures and old ladies gave them gifts that turned out to be magical at just the right moment? Plant/Payoff and moral lesson at the same time.

I’d also like to point out that if you happen to have both an Assembling the Team and a Training sequence in your second act, that can add up to a whole fourth of your story right there! Awesome! You’re halfway through already!

In a thriller or romantic suspense or urban fantasy or mystery — or in a fantasy like Harry Potter or The Wizard of Oz — there will be continual ATTACKS ON THE HERO/INE by the antagonist and/or forces of opposition. These will often start subtly and then increase in severity and danger. In a lighter romance these attacks can come from the antagonistic love interest, as in While You Were Sleeping, or the rival for the love interest’s hand (Made of Honor).

In a detective story, which is often also the structure of romantic suspense, paranormals, and urban fantasy, Act Two, Part One often consists very specifically of INTERVIEWING WITNESSES, FOLLOWING CLUES and LINING UP THE SUSPECTS, very often interspersed with ACTION SEQUENCES and ATTACKS ON THE HERO/INE. You will want to weave in RED HERRINGS and FALSE LEADS. And there’s another convention of the genre you’ll want to look at, which is THE DETECTIVE VOICING HIS/HER THEORY. Mysteries are by nature convoluted, because there are so many possible explanations for what’s going on, so don’t be afraid to have your detective or amateur sleuth just say what s/he’s thinking aloud. Your reader or audience will be grateful.

If you are using mystery elements, you will definitely want to break down several classics to see how these elements and sequences are handled. Murder on the Orient Express, Silence of the Lambs, Sea of Love, and Chinatown are great examples to analyze.

Also in the second act of many genres, you may be setting a TICKING CLOCK, which I’ll talk more about in an upcoming chapter on suspense techniques. Note that a clock can be set at any time in a story, not just in Act II.

And you’ll also want to be continually working the dynamic of HOPE and FEAR: you want to be clear about what your audience/reader hopes for your character and fears for your character, as I talked about in Elements of Act One.

A screenwriting trick that I strongly encourage novelists to look at is the filmmakers’ habit of STATING THE HOPE/FEAR AND STAKES, right out loud.

In The Proposal, the INS agent states the penalty for falsifying a marriage: Margaret will be deported, but Andrew faces a $250,000 fine and up to five years in prison. Yikes.

In Sense and Sensibility, numerous parallels are made between Marianne and Colonel Brandon’s tragic love, who ended up basically a prostitute who died in the poorhouse. Talk about fear and stakes! Very realistic for the period.

The writers often just have the characters say flat out what we’re supposed to be afraid of. Spell it out. It works.

All of the first half of the second act is leading up to the MIDPOINT. This is one of the most important scenes or sequences in any story — a huge shift in the dynamics of the story.

It’s so important that I will let you all take a breath now and deal with it in the next post.

- Alex

And if you'd like to to see more of these story elements in action, I strongly recommend that you watch at least one and much better, three of the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

I do full breakdowns of The Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone, Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on June 13, 2017 06:42

June 12, 2017

What does your protagonist WANT? (Dear Evan Hansen)

Congratulations to Dear Evan Hansen - winner of the Tony Award for Best Musical!!!

And our Junowrimo lesson for the day on a crucial story element.

If you're new to this blog, start here: Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

I am always saying that looking at musical theater is an excellent way to learn how to present Key Story Elements like Inner and Outer Desire, Into the Special World, the Hero/ine’s Plan, the Antagonist’s Plan, Character Arc, Gathering the Team – virtually any important story element you can name. Musical theater knows to give those key elements the attention and import they deserve. What musicals do to achieve that is put those story elements into song and production numbers. They become setpiece scenes to music. And you know how I’m always encouraging you all to SPELL THINGS OUT? Well, there no better way to spell things out than in song. The audience is so entertained they don’t know you’re spoon-feeding them the plot.

Yes, I know, you can’t put songs on the page. But - you can most certainly learn from the energy and exuberance of songs and production numbers, and find your own ways of getting that same energy and exuberance onto the page in a narrative version of production design, theme, emotion and chemistry between characters, tone, mood, revelation – everything that good songs do.

And one thing Broadway does very, very, VERY well is the DESIRE song.

It is critical for you, the author or screenwriter, to tell your reader/audience what your protagonist WANTS. Not just in Act One, but as early as possible in Act One. We must know what the main character wants so that we can want it for them. Or so that we can see how wrong the character is about what s/he wants so that we can root for her to get what s/he NEEDS instead.

Because the TWIST of almost any story comes from the protagonist NOT getting what s/he wants, but rather what s/he really NEEDS (or sometimes - getting what s/he wants in a totally unexpected way).

Let me just say part of that again. The reader/audience must know what the main character wants so that we can want it for them. This emotion is the basis of our engagement in the story.

And no art form is better than musical theater about spelling out what the protagonist wants in a way that doesn't just engage, but electrifies our emotions. Take a look at a few DESIRE SONGS in a row (that's what YouTube is for, people).

“Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” (My Fair Lady), “Reflection” (Mulan), “I Hope I Get It" (A Chorus Line). “If I Were A Rich Man” (Fiddler on the Roof), “I’m The Greatest Star” (Funny Girl).

Or just take a look at this one, "Waving Through a Window", from Dear Evan Hansen.

I don't think I have to say anything else - that amazing explosion of DESIRE speaks for itself. But don't you want that kid to get what he wants? Don't you even long for it?

That's emotional engagement. Do you have it your story?

- Alex

=====================================================

Announcements:

My producers on the Huntress Moon TV series and I are looking for feedback on the books and characters to help us with casting and other decisions. If you're interested in participating, The questionnaire is here.

=====================================================

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $12.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

And our Junowrimo lesson for the day on a crucial story element.

If you're new to this blog, start here: Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

I am always saying that looking at musical theater is an excellent way to learn how to present Key Story Elements like Inner and Outer Desire, Into the Special World, the Hero/ine’s Plan, the Antagonist’s Plan, Character Arc, Gathering the Team – virtually any important story element you can name. Musical theater knows to give those key elements the attention and import they deserve. What musicals do to achieve that is put those story elements into song and production numbers. They become setpiece scenes to music. And you know how I’m always encouraging you all to SPELL THINGS OUT? Well, there no better way to spell things out than in song. The audience is so entertained they don’t know you’re spoon-feeding them the plot.

Yes, I know, you can’t put songs on the page. But - you can most certainly learn from the energy and exuberance of songs and production numbers, and find your own ways of getting that same energy and exuberance onto the page in a narrative version of production design, theme, emotion and chemistry between characters, tone, mood, revelation – everything that good songs do.

And one thing Broadway does very, very, VERY well is the DESIRE song.

It is critical for you, the author or screenwriter, to tell your reader/audience what your protagonist WANTS. Not just in Act One, but as early as possible in Act One. We must know what the main character wants so that we can want it for them. Or so that we can see how wrong the character is about what s/he wants so that we can root for her to get what s/he NEEDS instead.

Because the TWIST of almost any story comes from the protagonist NOT getting what s/he wants, but rather what s/he really NEEDS (or sometimes - getting what s/he wants in a totally unexpected way).

Let me just say part of that again. The reader/audience must know what the main character wants so that we can want it for them. This emotion is the basis of our engagement in the story.

And no art form is better than musical theater about spelling out what the protagonist wants in a way that doesn't just engage, but electrifies our emotions. Take a look at a few DESIRE SONGS in a row (that's what YouTube is for, people).

“Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” (My Fair Lady), “Reflection” (Mulan), “I Hope I Get It" (A Chorus Line). “If I Were A Rich Man” (Fiddler on the Roof), “I’m The Greatest Star” (Funny Girl).

Or just take a look at this one, "Waving Through a Window", from Dear Evan Hansen.

I don't think I have to say anything else - that amazing explosion of DESIRE speaks for itself. But don't you want that kid to get what he wants? Don't you even long for it?

That's emotional engagement. Do you have it your story?

- Alex

=====================================================

Announcements:

My producers on the Huntress Moon TV series and I are looking for feedback on the books and characters to help us with casting and other decisions. If you're interested in participating, The questionnaire is here.

=====================================================

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $12.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on June 12, 2017 06:41

June 10, 2017

Junowrimo Day 10: Are you stuck? Do you have a PLAN?

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

One third of the way through June! This is a very good time to pause (briefly) and ask yourself:

WHAT'S THE PLAN?

The Protagonist's PLAN drives the entire STORY ACTION. The Central Action of the story is carrying out the specific Plan. And the CENTRAL QUESTION of the story is – “Will the Plan succeed?”

Take a favorite movie or book (or two or three) and identify the PLAN, CENTRAL STORY ACTION and CENTRAL QUESTION and them in a few sentences. Like this:

- In Philadelphia Story, Cary Grant’s PLAN is to break up Katharine Hepburn’s wedding by sending in a photographer and journalist from a tabloid, which he knows will agitate her and her whole family to the point of explosion. (So the CENTRAL ACTION of the story is using the journalists to break up the wedding, and the CENTRAL QUESTION is – Will he be able to break up the wedding?)

- In Inception the PLAN is for the team of dream burglars to go into a corporate heir’s dreams to plant the idea of breaking up his father’s corporation. (So the CENTRAL ACTION is going into the corporate heir’s dream and planting the idea, and the CENTRAL QUESTION is – Will they succeed in planting the idea and breaking up the corporation?).

- In Sense And Sensibility the PLAN is for Marianne and Elinor to secure the family’s fortune and their own happiness by marrying well. (How are they going to do that? By the period’s equivalent of dating – which is the CENTRAL ACTION. Yes, dating is a PLAN! The CENTRAL QUESTION is, Will the sisters succeed in marrying well?)

- In The Proposal, Margaret’s PLAN is to learn enough about Andrew over the four-day weekend with his family to pass the INS marriage test so she won’t be deported. (The CENTRAL ACTION is going to Alaska to meet Andrew’s family and pretending to be married while they learn enough about each other to pass the test. The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will they be able to successfully fake the marriage?

Now, try it with your own story!

- What does the protagonist WANT?

- How does s/he PLAN to do it?

- What and who is standing in his or her way?

For example, in my thriller, Book of Shadows, here's the Act One set up: the protagonist, homicide detective Adam Garrett, is called on to investigate the murder of a college girl - which looks like a Satanic killing. Garrett and his partner make a quick arrest of a classmate of the girl's, a troubled Goth musician. But Garrett is not convinced of the boy's guilt, and when a practicing witch from nearby Salem insists the boy is innocent and there have been other murders, he is compelled to investigate further.

So Garrett’s PLAN and the CENTRAL ACTION of the story is to use the witch and her specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate the murder on his own, all the while knowing that she is using him for her own purposes and may well be involved in the killing. The CENTRAL QUESTION is: will they catch the killer before s/he kills again - and/or kills Garrett (if the witch turns out to be the killer)?

- What does the protagonist WANT? To catch the killer before s/he kills again.

- How does he PLAN to do it? By using the witch and her specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate further.

- What’s standing in his way? His own department, the killer, and possibly the witch herself. And if the witch is right… possibly even a demon.

The PLAN, CENTRAL QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are almost always set up – and spelled out - by the end of the first act, although the specifics of the Plan may be spelled out right after the Act I Climax at the very beginning of Act II.

Can it be later? Well, anything’s possible, but the sooner a reader or audience understands the overall thrust of the story action, the sooner they can relax and let the story take them where it’s going to go. So much of storytelling is about you, the author, reassuring your reader or audience that you know what you’re doing, so they can relax and let you drive.

It’s important to note that the Plan and Central Action of the story are not always driven by the protagonist. Usually, yes. But in The Matrix, it’s Neo’s mentor Morpheus who has the overall PLAN, which drives the central action right up until the end of the second act. The Plan is to recruit and train Neo, whom Morpheus believes is “The One” prophesied to destroy the Matrix. So that’s the action we see unfolding: Morpheus recruiting, deprogramming and training Neo, who is admittedly very cute, but essentially just following Morpheus’s orders for two thirds of the movie.