Michael Hurley's Blog

September 10, 2020

“An enemy hath done this”

From Mere Christianity, by C. S. Lewis:

“The rightful king has landed . . . in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in a great campaign of sabotage. When you go to church you are really listening-in to the secret wireless from our friends: that is why the enemy is so anxious to prevent us from going.”

Early in the pandemic I wrote to an Anglican priest in London to say that I thought the massive overreaction by government and the resulting worldwide level of public fear relating to the virus was demonic. He wrote back to say that yes, he too thought “the virus” was demonic—and that it was our duty to stay away from church to show “support” for the government until the demon virus was defeated. He mistook my point.

The virus is not the tool of the enemy. Viruses come and go, and by all accounts Covid-19 is historically unimpressive, ranking near the bottom in lethality among all pandemics since the year 150. Fear is the enemy’s weapon, and irrational fear his trademark.

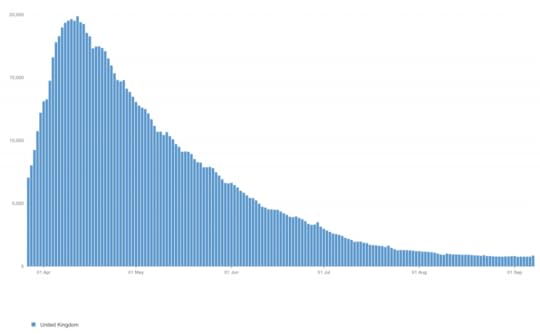

Below the C. S. Lewis quote is a graph published by www.gov.uk of the daily hospitalisation count from Covid-19 since the start of lockdown to yesterday, September 9. In observing this graph you might notice the conspicuous absence of a “second wave.” For several weeks running this summer, more people have died in the UK of influenza than of Covid-19. Yet from the constant fear-mongering by the government, which is dutifully repeated by the teachers union, the media and the clergy, you would think Covid-19 was the Black Death reborn.

How truly low the death count from Covid-19 is will never be known, because UK politicians eager to justify their panicked response and appease an increasingly fearful public weakened the standards for reporting medical causes of death that apply to other diseases, resulting in a system in which, literally, someone with a history of a cough or fever who was later hit by a bus was recorded as a “Covid death.” At the same time, Ofcom released “guidance” to UK broadcasters against reporting information that deviated from official government advice regarding the virus on grounds that to allow such information to reach the public would be “dangerous.”

But wait—aren’t “dangerous” ideas the whole point of free speech? Isn’t the point to allow supposedly “dangerous” ideas (just as freedom and democracy itself were once regarded) to be debated in the marketplace of ideas so that the best ideas become the best social policies? Stalin and Mao certainly didn’t think so, and neither apparently does Boris Johnson’s government.

With bishops and many clergy cheering from the sidelines, others unthinkingly falling into line, and others too frightened to speak, the government closed the churches in March without a fig leaf of resistance from the officer corps in Christ’s regular army. Just let those words flow over you again, slowly: the government closed the churches. Not the grocery stores, not the liquor stores, not the garden centres, but the churches. Could you have imagined it? For fear of a disease that 99.6 percent of the world’s population experiences as a brief and mild respiratory illness, they closed the church that Christ endured torture, suffering and death to purchase for us and that his early followers defended with their lives. And the bishops scolded us for objecting while they handed over the keys.

The shepherds frightened the sheep, and the sheep remain frightened. Church attendance that was already dropping like a rock has been decimated since the easing of restrictions. Is it any wonder? And won’t Satan be so pleased? Churches now look like the scene of some terrible disaster, strewn from one end to another with police tape and manned by citizen-gendarmes threatening to chuck us out if our mask slips or we dare to sing to or touch each other. The altars of our eternal salvation have become temples to our mortal terror. Christ warned us not to fear the enemy who could destroy our bodies but instead to fear the enemy who could destroy both body and soul in hell, but now it’s rubbish to all that. The new mantra is that we live or die by coronavirus alone.

This is fascism. This is groupthink. This is public hysteria. This is Evil with a capital “E.” And it has done incalculable damage to the Church. But the one thing it is not, is new or unexpected.

Growing up in the America of the 1960s and 70s, when most of us went to churches led by people who could still tell good from evil and weren’t afraid to say so out loud, it seemed to me that the church would be ever thus. I struggled to comprehend how the end times that Christ described in the 24th chapter of Matthew could ever come to pass, when “shall many be offended, and shall betray one another, and shall hate one another. And many false prophets shall rise, and shall deceive many. And because iniquity shall abound, the love of many shall wax cold.” Surely we would be too smart for that. Surely our faith would be too strong. Surely the zeal of our bishops and priests would never waver. Surely they would see the enemy coming.

I was wrong. Christ was right. No news there.

Today most of the bishops and clergy of the Church of England and many in the Catholic Church stand at the barricades, but they are the wrong barricades in the wrong fight. They have become footsoldiers in battles of political expediency, marching shoulder to shoulder with like-minded useful idiots who are oblivious or indifferent to the real danger. From their tufted battlements they snarl menacingly in readiness to fight—not for Christ’s gospel, but for the lunatic policies of climate alarmism or in political proxy wars alongside the armies of Neo-Marxism against the straw man of systemic racial oppression in modern Britain, by every measure the most racially tolerant country in Europe if not the world. And all the while the real enemy slips in unnoticed, literally stealing the flock out from underneath them. God help us.

And He will. Which is the Good News, and very good news it is, indeed.

In the parable of the sower, Christ’s servants plant the seeds of faith but wake the next day to find them overgrown with weeds. The servants ask whether they should rip out the weeds, so that the seeds might grow unimpeded. But Christ tells them no, let the weeds and the wheat grow amongst each other, until the harvest.

What we are experiencing now, with the government’s incomprehensible reaction to this virus, the public’s resulting hysteria, and the abject cowardice of our clergy, are “the weeds.” If you’re like me, you find your faith being choked off and struggling for nourishment by the banality of Zoom liturgies or masked, socially distanced and intimacy-free church services led by clergy that pretend to gaze at heaven while casting an ever-watchful eye at their treasure here on earth. But to despair over this would give the enemy the victory he most desires.

Let us return to the 24th chapter of Matthew and reassure ourselves with these words from the Son of God: “But he that shall endure unto the end, the same shall be saved.” In other words, now is not the time to lose faith, but to strengthen it. I know of no better tool fit for purpose than the Rosary.

Regarded by a long line of saints as a powerful weapon of spiritual warfare, the Rosary is a way for small groups of the faithful to defy the prevailing culture of fear by meeting in each other’s homes to pray communally for strength and faith to “endure unto the end.” Anyone who would like to pray in person with me is welcome to contact me at mike@mchurley.com. I encourage you to make the same invitation to others.

The Archbishop of Canterbury was right about one thing: the church is not a building. But it’s not an act of performance theater for spectators on a Zoom call, either. It’s wherever two or more are gathered in Christ’s name. Let us then gather—and touch one another, and kiss one another, and embrace one another, and feed each other bread and wine, and pray and laugh and cry and question together.

They can lock the churches, but they cannot shut the Kingdom of Heaven, for as Christ teaches us, “the Kingdom of Heaven is within you.” Boris Johnson has no jurisdiction there. Thank God for that, and be of good cheer. The victory has been won. Don’t let anyone convince you otherwise.

(C) 2020 by Michael C. Hurley

The post “An enemy hath done this” appeared first on Michael Hurley.

May 28, 2020

Land of Fear and Loathing

When I came to Europe from the United States in 2015 to walk the Camino (the 500-mile ancient pilgrimage through northern Spain), I had the good fortune to fall in with a genial group of Brits. I was planning to visit the UK after my pilgrimage to finish a novel and explore the world left behind by my grandfather. He was born a pauper in London in 1878 and came to America in 1903 to make his fortune and eventually send my father to Columbia University. As my new friends and I walked together, I wistfully described my vision of what life in the Land of Hope and Glory must be like, which they quickly dispelled as a delusion shared by most Americans: a strange amalgam of J. R. R. Tolkien, A. A. Milne, and Winston Churchill. “That England no longer exists,” they said—“except maybe in the Cotswolds,” one of them added, hopefully. When later I mused about how lovely it would be one day to meet a nice English woman—a schoolteacher or church-secretary type, perhaps—and settle down, their alarm intensified. “My God, man! Have you read no vintage British crime fiction? They are the ones who usually commit murder most foul!”

So much for preconceived notions. I did meet many charming and kind people in a land brimming with the history of western civilisation, but the Britain I encountered is indeed very different to the one of my idealized imagination. This first became apparent at a garden party in London when I found myself chatting with a school guidance counsellor. “So, how are kids doing these days?” I asked, intending only to make polite conversation and fully expecting to hear the kind of optimism that usually accompanies stories about children. But no, this woman told me that all was far from well and that kids in general were actually quite depressed. “Who could blame them,” she explained, “when the world will end before they reach our age?” As I listened, I was certain I was hearing some of that famous British dry wit. Not wanting to be caught out, I said nothing as I looked half-smirkingly at the woman and waited for her to break out into laughter. But she didn’t. She was talking about climate change, and she was deadly serious. I nervously excused myself to grab another drink before Armageddon.

I would have dismissed my encounter at the garden party to the admixture of gin and melancholy, except that I began to have similar encounters everywhere. Radio 4 daily sounded the same depressingly uniform tone of alarm over mankind’s bleak future. Even as American media were reporting historic levels of snowfall that were making roads to ski resorts in the Rocky Mountains impassable, one BBC reporter managed to find a community in Finland (or was it Iceland?) whose snowfall was (temporarily as it turned out) less than expected. With glum sobriety and absolute authority she informed listeners that this snowless wasteland was the Earth’s inevitable fate.

A ray of optimism shone through at one dinner party in Greenwich when the hostess announced that it would be another sixty years before all crops would cease to grow upon the face of the earth—at least allowing enough time, I secretly rejoiced, for the aforementioned guidance counsellor’s students to reach middle age. But hope was short-lived. Sitting in a pew at St. Luke’s Church in Charlton Village on Scout Sunday, I heard the vicar tell a squirming knot of terrified beavers the woeful news, recently announced by the Prince of Wales, that the world very well might end before their eighteenth birthdays—not from the rapture, mind you, but from global warming.

If apocalypticism is the new religion of Britain, the NHS surely is its God against whom no blasphemy may be spoken. I learned this the hard way. You may recall that the parents of the terminally ill infant Charlie Gard had privately raised millions of pounds to pay for a new form of treatment that had been tried with success by a highly-respected specialist at Columbia Hospital in New York. When I read that their child was being held hostage by the NHS and the European Court of Human Rights in Brussels, I lamented this sad fact in a post on my Facebook page. If a court in Montreal presumed to tell an American family that they couldn’t use their own money to seek treatment for their dying child at one of the premier medical research universities in the world, the Jefferson Memorial would spontaneously combust and there would be pitchforks and torches in the streets of Washington, D.C.

But this is not America, and I was unprepared for the deluge of opprobrium that would fall upon me from my British friends for daring to suggest that a decision of the NHS should be questioned in any way. The upshot of their comments was that the parents simply needed to get in line because the NHS certainly knew what was best for them. In a strange foreboding of the current lockdown culture, few Brits seemed to grasp that the issue in the Charlie Gard case was freedom—the freedom of parents to choose how long and hard to fight, at their own expense, for the life of their own child versus the power of the NHS to force them to give up on that life. The entire question for these social media scolds turned on whether the NHS could be trusted to make the right decision (yes), and whether that decision should be questioned (no), not whether the NHS had the right to make that decision instead of the parents. Sound familiar? I began then to understand that modern Britain has become exceptionally good at queuing up, shutting up, and doing as they are told. I understand that even better now.

Nigel Lawson, who served Margaret Thatcher as Chancellor of the Exchequer, famously said that “the NHS is the closest thing the English people have to a religion.” The COVID-19 pandemic combined Britain’s apocalyptic impulse with its religious fealty toward the NHS to create the perfect storm. So, it is unsurprising, I suppose, that the British public’s silent, abject submission to the government would persist well beyond the point where both the benefits of the lockdown policy and the perceived danger to the NHS ceased to bear any relationship to reality. Public opinion in Britain remains solidly in support of the lockdown even as information grows more discomfiting by the day that lockdown has achieved nothing so much as generational harm to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Whereas people in America suffering under lockdown have begun increasingly to do what Americans typically do, which is to demand their freedom, if recent polls are to be believed the British public seems to regard freedom as “dangerous” and to be begging the government to take more of it away from them. The Church of England, which in past crises has been a rock of stability and strength for the nation, now leads the pack of those who have decided to run for their lives. The Church closed its doors even to its own clergy as well as to private prayer and instructed clergy to refuse to answer the call of the NHS for volunteer chaplains to minister to the sick and dying. (Fr. Marcus Walker’s essay in the Times, pleading with the bishops to reverse this policy, and his lament that the Church of England could no longer call itself the national church if they failed to do so, was particularly painful to read.)

What on earth has happened to the Land of Hope and Glory?

The Sunday night speech the prime minister gave as his first address to the nation following his illness was one of the most transparently dishonest and condescending in recent political history. He spoke to the nation not with sober, measured reason but with an almost comically overwrought, infantilizing sense of urgency, strangely reminiscent of a football coach talking to a team of youngsters down in points at half-time. Only by speaking to the nation as children could he feel free to pretend as if reams of thoughtful analysis and weeks of data had not been published and read by his audience that flatly contradicted the projections on which he based the decision to plunge the nation into an historic depression. But as it turned out, Johnson gave his audience exactly the degree of respect they deserved. Hilariously, public reaction to the speech focused not on Mr. Johnson’s failure to come clean about the deeply flawed models that led to the lockdown but on his failure to explain more clearly the various new restrictions on public life that the public was all too eager to obey.

But the problem is both bigger and newer than the age-old sins of political dishonesty and cowardice. After all, it is not as if the British public doesn’t know the truth. They do. Instinctively, they do. A disease with an overall infection fatality rate, according to the CDC , of 0.26 percent and 0.005 percent for persons under 50 that as of today has killed fewer than 360,000 people worldwide is not “the most serious public health crisis in generations.” It was never going to kill 550,000 Britons if the government did nothing, as Professor Neil Ferguson and his team at Imperial College of London infamously warned. Boris Johnson surely knows this now, if he didn’t know it then. But by joining him in an elaborate pantomime in which we pretend that those fears were justified (and averted only by his swift action), we have left the real world.

In this new world, the weaving of the emperor’s new clothes from the brightly coloured cloth of an imaginary narrative will become a national industry to replace the thousands of actual industries shuttered by the lockdown. The care and feeding of this narrative, i.e., that our economic devastation and loss of personal freedom to the “new normal” are part of the sacrifice necessary to rescue the nation, is sure to keep us all busier than ever (along with, let us not forget, attendance at the weekly worship service of clapping for the NHS).

The 1.3 million who die annually from another deadly but strangely less newsworthy communicable disease—tuberculosis –dwarf the number who have died of COVID-19, as do the numbers of children who die each year of seasonal flu (or even lightning strikes, bizarrely), compared to those who die of COVID-19. Yet the British public, egged on by a cult of safetyism within the teachers union, is at the moment needlessly tearing itself to pieces over the decision whether to send children back to school. Many of us seem to prefer our fears or, more to the point, the feeling of safety and security that comes from looking to others to protect us from our fears—even imaginary ones. Like children, we huddle under the covers in terror of the monster that may or may not (but could, statistically speaking) live under the bed.

Unlike some, I do not kindle hope that the many able commentators who keep pointing out the continuing tragedy of the lockdown policy and the absurdity of the “new normal” of social distancing will eventually win the argument with their fellow Britons. There is no argument to be won. As the American cartoon character Pogo would say, “I have met the enemy, and he is us.”

We are the new normal. We are not the people our grandparents were. We are the ones eagerly participating in this extravagant charade that we are all about to die from shaking hands with our neighbours or walking outside without a mask. We have the power to choose the kind of society we live in by refusing to give aid and comfort to the scaremongers through our silence. Too many of us simply refuse to speak.

In one of those interminable, television binge-fests that lockdown has given us, I chanced upon an old movie filmed in England in the early seventies entitled “Swallows and Amazons.” The story recreates a young family’s holiday to the Lake District in 1929. With their mother staying in the cottage on shore and giving her blessing, four siblings ranging from 8 to 14 years of age pack their own supplies, sail their small boat to an island in the lake, make a campfire, sleep in tents for several nights, and live out various adventures as imaginary castaways on a pirate island. The story of children trusted with this much freedom (and the risk of harm that freedom brings) had to be real enough to seem plausible to the British audience that loved it in 1974, but it is the stuff of utter fantasy (if not criminality) today. Today, we are being governed, and our news is being curated and delivered to us, by the generations of neurotic helicopter parents and their children that followed the ones who lived in 1929.

Do you remember the massive, nationwide lockdown in the UK during the 1968-69 Hong Kong flu that took an estimated one to four million lives worldwide? Our grandparents don’t remember it either, because it never happened. Life carried on as usual, which is why if you were alive back then, you probably don’t have a memory that a disease as deadly as, if not ten times more deadly than, the current pandemic swept through the world around you. The BBC wasn’t broadcasting daily death counts and doing its damnedest to frighten the bejesus out of all of us. It never occurred to our grandparents to react to that tragedy by immolating the society we would inherit from them. As a result, today we look back at 1969 and remember not cowering in fear from a virus but swallowing our fears and putting a man on the moon.

We are not like our grandparents, and they were nothing like us, and that has made all the difference. The Britain of today is a health-and-safety culture that has largely abandoned the religious faith that once gave it a sense of transcendent meaning. As a result it finds itself obsessed with every threat—real or imagined—to its materialist world view and sees goblins of risk and impending doom around every corner.

Drifting off to sleep in front of the television and lying next to the English schoolteacher I married two years ago, I realized that I was taking a risk. The right to question authority, most especially where the NHS is concerned, is not one of the freedoms Britons, much less American interlopers living in Britain, can take for granted anymore. Who knows? Some might even say I have good reason to fear murder most foul. But life and love and the choices we make to give meaning to both are worth the risk. Here’s hoping that Britain remembers this before it’s too late.

______________________________________

(c) 2020 by M. C. Hurley

Michael Hurley is an American writer and retired attorney living in London. He stays in touch with readers at www.mchurley.com.

The post Land of Fear and Loathing appeared first on Michael Hurley.

May 7, 2020

A Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury

16 April 2020

Most Revd. Justin Welby

Archbishop of Canterbury

Lambeth Palace

London SE1 7JU

Dear Archbishop Welby:

I am writing to express my concern over recent actions taken by the Church of England at your direction in regard to the COVID-19 pandemic which, I am very disappointed to add, enjoy the full support of the clergy in my own parish of St. Luke’s in Charlton Village. I believe the Church leadership is gravely in error in regard to the decision to bar clergy from ministering directly to the sick and dying, to forbid even the limited use of churches for private prayer, to ban clergy from entering their own churches alone for celebration of the mass, and, by all these actions, to foster the message that the Church is “non-essential” to society’s efforts to cope with this pandemic. I share these thoughts with all the humility and respect owed to your high station, with the greatest sympathy for those suffering from disease, and with full knowledge that I sit in a place very remote from the terrific fray in which you and the clergy now find yourselves. From such a distance it is always easy to throw stones. I trust you to accept that I do not do so lightly or with malice.

I hold no office in the Church, nor can I claim to have earned the right to address you on this subject through long years of labour and devotion to my faith or any personal qualities of holiness or charity. I am a backbencher and backslider of the first order. But in rare times such as these, I think it behooves all of us who perceive the danger to sound the alarm, even if that noise is heard chiefly by our own conscience and the judgment of posterity.

Like most people trying to make sense of what we are hearing and reading, I am fully persuaded that COVID-19 is a dangerous disease made more dangerous by the fact that it is poorly understood. Although with each passing day it becomes increasingly clear that the rate of infection is far higher than initially believed and the mortality rate blessedly lower than initially feared, COVID-19 remains a deadly virus that presents unique challenges for healthcare providers. For that reason, I share the view that some form of temporary societal quarantine was necessary to slow the rate of infection and soften the blow to the healthcare system. Though I believed early on and still believe that a program of targeted protection of the elderly and infirm accompanied by vigorous testing would have been far preferable to a nationwide lockdown and the resulting injury to the fabric of society, I am not an epidemiologist or a politician. I accept that people far more knowledgeable than I and with greater responsibility are called upon to make difficult decisions quickly in the face of scientific uncertainty as to the best course of action. However, it remains your duty and mine to ensure that any course of action that impinges upon our sacred freedom of worship is regarded with suspicion, continually and publicly questioned, limited in time and scope, and tailored closely to only those measures that serve a compelling and overriding societal interest. It is in this duty that I find the Church of England has failed in a most stunning fashion.

Only in the rarest of circumstances in the last 800 years have the churches in England closed their doors and forbidden the public celebration of the mass. During that time the people of this island have suffered wars, persecutions, plagues, pestilence, bombings, riots and revolutions of such terrific violence and devastation that even to enter a church to pray was at times an act of remarkable sacrifice and courage. Yet except during pandemics more deadly by orders of magnitude than the one we face today, and despite wars far more deadly than disease, the people and their priests still regularly came together in the face of danger to worship in their thousands. They did so in obedience to the Lord’s command to come together bodily, in the physical presence of other believers, and share not virtually but corporeally in the Eucharistic meal. They did so in obedience to the apostle’s enjoinder against forsaking “the assembling of ourselves together, as is the manner of some.” They did so in obedience to the promise that “the gates of Hell” should never prevail against the Church entrusted to our care. They did so not in the mystical belief that their faith protected them from the risk of harm, but in the firm conviction that the act of worship in physical proximity to other believers was worth that risk. It is for this reason that I find your suggestion that we should not feel greatly deprived by becoming an online community because the church is “not a building” to be somewhat misguided.

The Church is not a building, but it is and always has been a physical gathering of people of likeminded faith, and for centuries those gatherings have taken place in the buildings we call churches. In fact, no one moreso than the clergy has held up these buildings as sacred places for veneration by the faithful. There is a plethora of rules surrounding whether, how and when a wedding will be permitted inside a particular church building versus somewhere else. It was only a few months ago that my own vicar was asking our tiny congregation to come up with £80,000 to refurbish the sound system in our sanctuary. Through the centuries, the Church has been content to sacrifice a far greater number of lives to the construction, maintenance, improvement, and defence of the many cathedrals of England than could be equalled today even if every victim of coronavirus dropped dead on the steps of Westminster Abbey.

I don’t by these remarks mean to question the decision to suspend public worship services temporarily. Although I might wish that we had at least attempted to hold more frequent services for fewer people at each whilst observing social distancing, perhaps such a policy would not have been feasible. It is always easy to second guess decisions made in moments of urgency under threat to human life, and I do not intend to do so here. However, given the costliness of the faith handed down to us through the centuries, one would hope we would consider the idea of closing the churches and forbidding public worship only with the gravest reluctance, the utmost sober and thoughtful deliberation and debate upon unimpeachable scientific evidence, prior consultation with the public on whose behalf we presume to act, and continuing determination to press the government on all possible lesser alternatives to a full ban. Clearly this is what Pope Francis was trying to do when he refused the government’s order to close the churches of Rome, kept them open to private prayer, encouraged priests to enter their empty churches to celebrate the mass, and exhorted them to continue to minister directly to the sick and dying despite the risk to their own health. I am sorrowed to say that his record presents a stinging and, frankly, embarrassing indictment of your own.

Far from acting with circumspection and reluctance, by banning your own priests from entering their churches for private prayer and the celebration of the mass, you have exceeded even the government’s directive. The point is not that there is something “magic” about holding church inside a church. It is that your prohibition was needless and arrogant. Catholic priests all over the UK are streaming services from inside their churches to their parishioners with no deleterious effect on the pandemic. But however pointless, you can be sure that your decision, which aggrieved some of your own clergy and was widely reported in the press, had a big impact. You succeeded in sending the public the message not just that churches are “non-essential,” but that Christian people and their churches don’t necessarily go together. When I first moved to England from America a few years ago, I was gobsmacked to read a story in the Guardian on the declining relevance of the Church of England under the headline, “England’s churches can survive, but the religion will have to go.” It should be cold comfort to you that today, the Guardian is cheering your actions the loudest, whilst the editors of the Telegraph recently offered their opinion under the headline, “When Britain Needed Them Most, Why Did the Churches Lock their Doors?” Yet this is hardly the Church’s gravest error.

Last week the papers reported [1]that you have now forbidden the clergy to minister at the bedside of the sick and dying—the very task that was the central focus of Christ’s ministry and the chief ministry of priests in the 2,000 years since. My own vicar confirmed that she had received this instruction and, to my great sadness, that she agreed with it. Let’s be frank: the Pope of Rome is encouraging the faithful to “pray . . . for our priests, that they may have the courage to go out and go to the sick people, bringing the strength of God’s word and the eucharist, and accompany the health workers and volunteers in this work that they are doing,” whilst the Archbishop of Canterbury is telling priests to run for their lives. Could the contrast be any more stark? Could the scripture, “For whoever wants to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake and for the gospel will save it,” be any more clear?

So surprised was I by news of your directive that priests should absent themselves from the sick and dying that I contacted two Catholic priests in London to enquire whether this is an order the government has foisted upon all clergy over their objection. It is not. They informed me that Catholic priests equipped with personal protective clothing are continuing to give last rites and minister at the bedsides of COVID-19 patients within hospitals. One called me from his car just as he was pulling up to minister at the home of someone dying of the disease.

The perverse justification for this policy given by the Church of England is that by refusing to bring to the sick and dying the comfort of a priest’s physical presence and the power of the Eucharist, we are carrying out Christ’s command to “love our neighbour.” I must tell you, there are no words in recent memory that have sent a colder chill down my spine.

Lately I have been meeting with a small group to study the works of C. S. Lewis. He would teach us to recognize the lies of Satan by being attuned to the fact that what Satan asks us to accept as “true” is often not just a lie but the polar opposite of truth. Thus was Eve told that by eating of the forbidden tree, not only would she not die, she would become “like God.” In the same fashion are we deluded if we believe that by abandoning the sick and dying to lonely suffering we are carrying out a great mercy instead of a great abomination. I imagine Satan congratulating himself over this strategy to subvert the Church by denying the Eucharist and the presence of priests to the sick and dying under the guise of “loving your neighbour” and alternately kicking himself that he didn’t think of it sooner.

I am well familiar with the argument that all these measures are necessary to keep from spreading the infection and overwhelming our hospitals. However, to suggest that it is essential for doctors and nurses to risk their own lives (and risk carrying the infection to others outside the hospital) by being physically present to comfort the sick and dying, but that it is non-essential for priests to do so, is to perpetuate the atheistic idea that there is nothing beyond the material world and nothing more important than our material survival. Astonishingly, the Church of England has now become a chief sponsor of that deadly message.

Since the start of this crisis, we have been subjected to the mantra that we must at all costs “protect the NHS”—a phrase now recited so often and so robotically as to have become eerily reminiscent of the slogans of totalitarian regimes. We can scarcely get through an online worship service that does not include several reminders that “protecting the NHS” is the overarching goal of all that we do. In your YouTube video response to the recent uproar over church closures you suggested once again that protecting the NHS must be our primary aim.

But of course it is not our primary aim. Not since Alec Guinness tried to defuse the bomb in The Bridge on the River Kwai has an Englishman so thoroughly confused his ultimate mission with the task at hand. Your overarching duty and ours in this crisis (as at every other time) is not to “protect the NHS” but to defend the faith. As a gauge of how well the faith is faring in the midst of our constant deification of the NHS, you might reflect on the fact that when the Prime Minister was recently released from the hospital, he gave a five-minute speech profusely thanking the NHS without ever mentioning God or thanking the British public for their prayers for his recovery.

I took pains before writing this letter to express my views to the clergy at St. Luke’s, then to consider their responses, and also to listen to your remarks online and in the press. I find myself greatly unpersuaded of the justness of your cause. I have come to the sad conclusion that the Church of England and I should part ways. By copy of this letter, I am asking the Rev. Elizabeth Newman, Vicar of St. Luke’s Church, to remove my name from the electoral roll.

I do not suggest that my view alone is valid or that others cannot live out a full and meaningful faith in the Church of England. But speaking for myself, I cannot celebrate God’s gift of life among those who would build altars to the fear of death.

Yours sincerely,

Michael C. Hurley

cc:

Rev. Elizabeth Newman

St. Luke’s Church

The Village, Charlton

London SE7 8UG

_____________________________________

[1] “Coronavirus: Bishop Bans Clergy from Bedsides of the Sick and Dying,” by Patrick Kidd, April 9, 2020, the Times: “Members of the Church of England clergy who have volunteered their services as hospital chaplains during the crisis have been told that they will not be allowed to minister to any sick or dying patients at the bedside, even when wearing protective equipment, because of the risk of spreading the infection.” Full article here.

See, also: “Clergy Must be Free to Minister to the Sick in this Crisis,” a comment written by the Rev. Marcus Walker, Rector of Great St. Bartholomew’s Church (Church of England) in London, in protest of this policy, published on April 9, 2020 in the Times: “Almost 900 years ago my predecessor Rahere, sometime courtier (and maybe jester) in the court of Henry I, founded two institutions which have survived to this day: the church of St Bartholomew the Great and St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Through Black Death, plague, and cholera they have stood together and served the people of London. But not today. Because today the Church of England has forbidden its parish clergy from assisting — beyond the most basic functional tasks — the hospital chaplains in their job. This is no abstract problem. Barts Health NHS Trust, which runs the eponymous St Bartholomew’s Hospital along with three other east London hospitals, has been put in charge of the new 4,000-bed Nightingale Hospital. To serve these five hospitals, all of which are dealing with Covid-19 patients, the trust has two Anglican chaplains able to serve at this time. Two. They estimate that they need 11 to cover this crisis. Last week they put out a plea to the clergy living in London to come and support them in their essential ministry. But can they use us? No. The Church of England has suddenly changed its policy: priests volunteering as chaplains ‘will not themselves minister to sick or dying patients at close hand’. This is not the opinion of other religions and denominations, who have found ways of safely recruiting and dispatching people to minister to their own faithful — and quite rightly. It is only the Established Church which has decided not to allow the upscaling of its presence. The two chaplains, divided (by some miracle) over five different locations, and working all hours of day and night, will have to engage in this desperately important but hugely challenging ministry by themselves. When we are ordained, every single priest is told by the bishop ordaining them that ‘Priests are called to be servants and shepherds among the people to whom they are sent . . . They are to minister to the sick and prepare the dying for their death’. Today we are banned from doing this, not by a hostile government or a suspicious health service but by our own Church. I beg the bishops to reverse this decision before we forfeit for ever the right to call ourselves again the national church.”

The post A Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury appeared first on Michael Hurley.

September 23, 2018

The Thing About Jill

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

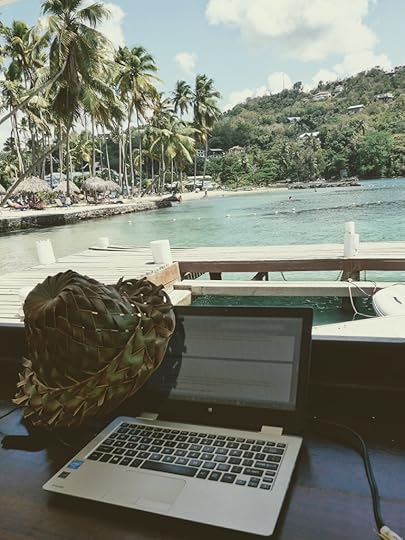

Jill in Santiago de Compostela, September 2018

As many of you reading this surely know, I am engaged to be married to a lovely English woman named Jill whom I met three years ago while traveling in London. Since that time a lot of water literally has passed under the keel for both of us, as we acquired and patched up a simple old boat and sailed her by ourselves from France to the New World. Two of the last three years have been spent rubbing along together at sea and in various idyllic anchorages in the warm and sunny West Indies, happily without the friction of excess clothing.

Following in the wake of Columbus, we made the wonderful discovery that we love each other, get on quite well, and would like to spend the rest of our lives together. Toward that end I have begun the long, slow march to British citizenship, and we have planned our march to the altar (as best anyone can make an altar of a rowing club on the Thames) for the 20th of October.

It was in service of our wedding plans that we met two months ago with our lovely and wise friend Linda Donnelly, the celebrant who will extract (one hopes) an emphatic “I Do” from each of us in the presence of more than a hundred friends and family. Linda is a much-sought-after wedding minister, and part of her charm is the personal touch she adds in saying something meaningful about the bond that holds two people together in the ageless institution of marriage. Quite naturally, then, during our planning meeting last summer she asked each of us to send her a short statement of what makes the other person unique compared to all the other lovers and partners we have ever known. At that time we we were due in three weeks to begin a 500-mile pilgrimage on foot along the ancient Camino de Santiago in northern Spain (where I sit as I write these words). Jill dutifully composed and sent her statement to Linda before we left. I, despite posing as the writer in the relationship, procrastinated with my assignment for months, rolling it over in my mind each day as I trudged mile after mile through mountains, little towns, lush vineyards and along the sun-baked, dusty paths of the Camino. It would have been easy enough to dash off something pithy and charming and sweet, but I hesitated, and I wasn’t sure why. Then, one day it hit me.

I was standing in a place famously known to Camino pilgrims as the Cruz de Ferro, the “iron cross.” Here at the highest point along the 500 miles of the Way of St. James from St. Jean Pied de Port to Santiago de Compostela, a tall cross stands atop a mound of small stones. The stones have been left there in the hundreds of thousands by pilgrims who carry them on the Camino to symbolize a particular burden, often some grief or sadness or self-doubt or anger, they wish to let go.

The stone I left behind at the Cruz de Ferro symbolized my deep, gnawing sadness over my only daughter Caroline, now 26, who has refused to see me or speak or write to me for nearly five years. In that time and in my absence she has graduated from college, married a fine young man, and brought into the world a grandson I have never met. Like so many daughters of so many angry and embittered ex-wives, she felt compelled to choose sides in the ugly aftermath of the divorce that ended my 26-year marriage to her mother twelve years ago. Caroline is my heart’s delight and the reason I climbed up to the iron cross, but my sadness and Caroline’s disappointment in me are not the point of this story.

As I laid my stone on the pile, I prayed for the grace to let go of my grief but vowed never to let go of Caroline. The reason for the difference, of course, is that a father’s love for his children does not depend on their love for him. Nor does it depend on them having pleasing personalities or admirable traits of character or the right opinions, qualities, attitudes, or allegiances. It doesn’t pale with time or rejection. Long before I watched each of them enter the world, before I first held their pink, curling hands and hurriedly counted all their fingers and toes, I loved my children unqualifiedly and unconditionally because they are a part of me and I am a part of them.

When I dropped Caroline’s stone on the pile, without aforethought I decided to pick up another to symbolize the new burden I was gladly undertaking for the rest of my life—namely, the promise to care for and comfort, love, honor and defend the woman standing beside me on that mound of rocks. The perfect stone appeared to me at once as if by providence. What made it perfect was not its shape but its many colors and its smoothness. In that moment I realized at last my answer to the wedding celebrant’s question.

It is certainly true that Jill is nothing like any other woman I have ever loved in ways almost too numerous to mention. She rides on an even keel. She goes with the flow. She’s plenty stubborn but never cross or curt. She’s more than a little game for adventure. She has a list a mile long of food she won’t eat, but she always wants half of whatever I’m having. Little things don’t upset her apple cart. She’s not overly into money and “stuff.” She tends to old friends like heirloom roses and grows new ones like daisies. She doesn’t see sexuality and femininity as mutually exclusive realms. But I don’t love her, nor did I resolve to marry her, because of these qualities. It is also certainly true that Jill loves me with more honest, genuine affection and devotion than every other women I have ever known, but neither is that the chief reason I want to marry her. I didn’t propose to her because she possessed new features or capabilities or improvements lacking in the women I had known before, as one might choose a new vacuum cleaner or lawn mower.

Jill and I came together in the usual way through the fireworks of mutual attraction, but it’s what happened afterward that really tells our tale. Like small stones rendered smooth from countless small abrasions, we rubbed along together through storms both material and ethereal and came out the other side so well accustomed to each other’s ways, so reliant on each other’s touch and reassurance and laughter and friendship, that the question of “what attracts” me to Jill now seems almost unanswerable. Her many wonderful qualities, like her physical beauty, are something I find lovely and fascinating but not essential. My bond with her is something at once obviously different from but in important ways very similar to the bond I feel for my children. It is not founded in merit or mutuality but in love—and true love, it seems, has rendered me incapable to engage in the cold, objective analysis of a beauty pageant where Jill is concerned. Jill wins my vote for the title of Miss Universe by acclamation because . . . because, well . . . because she’s the only woman in the universe as far as I can tell.

And a girl can’t get any more unique than that.

The post The Thing About Jill appeared first on Michael Hurley.

December 10, 2017

A Eulogy for My Brother

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleJay Edwin Hurley, Jr.

July 10, 1941 to December 3, 2017

What has come to me today, and to all of us, is the unexpected, unwelcome and, frankly, impossible task somehow to punctuate the end of my brother’s life with a statement of what his life meant to us—unexpected, for me, because even though I knew Jay was not well and hadn’t been well for a long time, I never imagined this day would come so soon. Jay was only 76 years old. To some that may seem a ripe old age, but not to me. Jay and I shared a father who, despite a disastrously destructive lifestyle that would have killed most men a dozen times over, lived longer than his eldest son. Jay died almost two decades younger than our Grandfather Hurley, who was born into poverty in England in a century that did not know penicillin or most of the vaccines we take for granted today. My brother died many years sooner than did our mother, and her mother before her.

I don’t mention this as a shortcoming to find fault with Jay somehow for not giving us more of himself. The truth is, I’m a bit angry with God. I have been a trial attorney for most of my life. I rarely lost a case and it never rested easy with me when I did. I was also not over fond of judges, but when things didn’t go my way I made my objection and yielded gracefully to the judgment of the court, as every lawyer must do. I lost my appeal to God about Jay, and I take exception to that decision. I wish here and now to note my objection for the record to the judgment of heaven that Jay should have left us so soon. One day I’ll have a hearing with the Almighty, because this world is not the court of last resort. My day before the throne of heaven will come, and when it does, I intend to ask the judge of us all why Jay’s time on Earth could not have been a bit longer, a bit easier, and his burden a bit lighter. I am looking forward to his explanation, because as scripture teaches, now we see as through a glass darkly, but then we shall see face to face.

Now, all we can do is yield gracefully to the judgment of heaven, but there is a benefit to us in doing so. We whom Jay has left behind should abandon any delusion that, somehow, the progress of medical science has made life something other than what it has always been: temporary and precarious and often unfair. Life remains as it ever was: a precious gift, not a guarantee.

And so if I may, I would like to take a few moments to share some sense of the gift that was given to me in the life of Jay Edwin Hurley, Jr.

I came here literally straight off the boat—by that I mean a sailboat of course, in Antigua, the West Indies, and I have Jay to thank for that. I am so grateful that Jay lived to see his little brother cross the Atlantic in a good old boat. I am so grateful that I got to send him a letter from a foreign port of call enclosed with the flag that had flown from my rigging. Jay didn’t just teach me to sail when I was a boy. He did something much more important. He infected me with an incurable wanderlust for sailing. I remember well the day when I succumbed to this disease. He and I were out in Chesapeake Bay in a nineteen-foot sloop he had rented by the hour on the South River, and suddenly there was nothing on the horizon—no limit, nothing stopping us. Nothing but water and time. And I looked down into the small cabin and imagined that if we stuffed a duffle in there filled with food and water, we could just keep going. Little did either of us know then that one day, I would do just that.

Jay was very different from me in many ways. He had a math-science brain. I did not. He was always the go-to guy in our family to fix anything—the TV, the car, the radio—whatever. He could build things, too, including boats. He was a science and technology geek. I was at his house once in the seventies when he came to me with something tiny in his hand. When I asked what it was, he said, “This is the reason the Russians will never catch us.” It was a silicon chip at the dawn of the age of microcomputers. Unlike my brother, I was confounded by math and mechanics. I loved music and writing, but the great thing about sailing is that it’s poetry and music in motion. I loved the romance of sailing. When I grew up, I bought my first sailboat before I bought my first house. Sailing became the language Jay and I could always speak together, and a way to understand each other. Since that day on the South River and many other days like it that he and I spent together, I have sailed thousands of miles. Jay I don’t believe ever sailed more than 28 miles from home, but that didn’t matter. We spoke the same language, and I would not have seen a single one of those thousands of miles were it not for him.

I looked up to Jay, and not just because he was an inch taller and sixteen years older. Sometimes he would speak so softly that you could barely hear him, and I never knew why he was like that, but in remembering his life it occurred to me that in all those years I don’t think I ever asked him to speak up. I just listened harder. I never corrected him. I never wanted to change or improve him. I wanted Jay to be Jay, and to succeed just the way he was. In his quietness he had an authority that I respected, and others did too. At my wedding reception in 1981 there were probably a dozen buddies of mine—big guys—who had carried me off in my tuxedo and were getting ready to throw me in the pool. Jay stopped them with a look and a word, and they dropped me like a rock.

Perhaps he should have let them throw me in. When my marriage ended badly twenty-five years later, there were a lot of people who were surprised and disappointed in me, some of whom weren’t talking to me, even in my own family. I remember my failings as a husband being hashed over at one family gathering, when Jay interrupted the conversation and said, in a mocking tone, “Off with his head!” In that one outburst, he took the criticism to an absurd extreme to demonstrate the absurdity of nurturing feelings of spite toward the people who are our flesh and blood. He was reminding everyone of the obvious: “This is Mike. He’s our family. Of course we’re not going to turn our back on him, so let it go.” Jay never judged me for my failures—not once, even when I managed to capsize and snap off the mast of his boat while he was away on his honeymoon with Donna. He gave me some advice, instead. It was one of his favorite sayings whenever I would get ready to leave. “Keep the shiny side up,” he would say. These were words of wisdom that applied to boats, cars, motorcycles, and life. It meant, do your best to stay right side up, and keep going.

That’s what he would tell me today, if he could, and what he would say to all of us. I intend to do my best to remember that advice, and to follow it in his honor. To Jay, I offer a prayer for fair winds and following seas, and to God I give thanks for the brother he gave to me, and for the time we had together. Amen.

The post A Eulogy for My Brother appeared first on Michael Hurley.

September 3, 2017

Letters from the Sea: A Sinking

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

The Prodigal, 500 miles south of Nova Scotia

A

s a few friends will recall and the few readers of scattered press reports at the time have surely forgotten, I was sailing alone, ten days out of Charleston, when I made the decision to abandon a leaking, weather-beaten, fifty-year-old ketch named Prodigal in rough seas about 500 miles south of Nova Scotia. The month was June, in the year 2015. I was one-third of the way to Ireland on a 3,500-mile passage I had planned for months. The implosion of my second marriage had come just three weeks before. I had set sail anyway, already mired in one storm, headed inevitably for others.

As was the case with most of the boats I have acquired through the years, I had bought Prodigal for a pittance and fitted her out for a king’s ransom. I sailed her for a week up the Chesapeake Bay from Norfolk in 2013 and solo for seventeen days nonstop on a shakedown cruise to Bermuda and back in June 2014. Mechanical wind vane self-steering gear—the indefatigable but dear Monitor brand—freed me from all steering responsibilities offshore and allowed me to get snatches of sleep at night. The split ketch rig made for steady sailing in rough weather with the mainsail furled and the mizzen and foresail (the smaller sails at each end of the boat) flying.

Prodigal had leaked a bit on the 2014 voyage to Bermuda, but no more than could be easily mopped up with a few swipes of a sponge from the cabin sole. She was an old boat, but I am an old man, and we hardly begrudged each other a few imperfections. The passage to Ireland was different. After a glorious week of good weather, Prodigal took quite a pounding in heavy conditions and began leaking more than before. The United States Coast Guard (not at my invitation but of their own volition or someone else’s), was following my progress with uncharacteristic interest, as I discovered when their New York group began communicating with me by satellite text messages. They expressed concern short of alarm at my terse report to Facebook friends, at the time, that I was “taking on water.” (I concealed my concern approaching alarm that the government had the time, interest and ability to peruse my Facebook posts.)

The Coast Guard offered a rescue. I politely declined and stoically assured them I would be fine, not realizing at the time that my automatic, electric bilge pump, throbbing away deep in the bowels of the ship and unheard above the fracas of wind and wave, was pumping out water not quite as fast as it came in and steadily draining my battery, giving me a false sense of security as to the rate and volume of the leak.

Why draining the battery, you ask? Because on a sailboat and most especially a sailboat built in the sixties, the motor is the source of electricity, and the motor itself is more of an ornament than a main source of power. This owes to the fact that there is only a very small space in the slender, lovely yacht designs of the sixties into which to squeeze a motor at all, and an even smaller space in which to squeeze a fuel tank. Motors on sailboats are called “auxiliaries” for this reason, because to depend on them primarily much less desperately for anything (including generating electricity to charge batteries and run bilge pumps) is folly. It’s rather like depending on your 110-pound girlfriend to beat up the loud-mouthed guy in the bar, or depending on the baloney sandwich in your lunchbox to save you from starvation. Both are there, yes, and both will function after a fashion, but not very well or long. Relying on an electric bilge pump at sea, far from fuel docks and diesel supplies, to continuously evacuate an ongoing leak is never a long-term solution—and being 1000 miles out into the Atlantic in a 30-foot boat, carried inexorably northward by the Gulf Stream, is the very definition of long-term.

Prodigal, an Allied Seawind Ketch built in 1965 in the Catskills of Upstate New York, was a tender sort of yacht—tender being a term that refers to the propensity of some boats to tilt over quickly and far when a breeze hits their sails. In Prodigal, this characteristic stemmed from a design that combined a narrow beam with a shoal draft, “shoal” meaning shallow and “draft” meaning the depth to which the keel extends below the water. Boats with narrow beams and tall masts need long, heavy keels filled with lead to counteract the force of the wind on the sails above the water. That’s because the more the wind blows a boat over sideways, the higher she lifts her keel, and the heavier and longer the keel, the more force gravity exerts on it to return the boat to level. Once a boat gets underway, the energy of the sails and the keel acting at cross purposes is expelled preferably in forward motion, not continued sideways motion to the point of capsizing. It is the envied characteristic of a deep-keeled boat that the wind can blow her over only so far until the force of the wind upon the sails can lift her keel no higher, at which point the boat stops absorbing all that wind energy by heeling sideways and converts it to forward motion instead, boring through the waves like a bus. Here endeth the lesson of keels and wind and the mysterious motion of boats.

But deep keels are problematic for the majority of American sailors who never sail in the deep, blue waters of the sea and instead spend their weekends skimming over shallow, muddy estuaries like Chesapeake Bay and Pamlico Sound. And so Prodigal’s designers, like those of many other American boats, saw fit to give her a lightweight keel that extended only a brief four-feet and some inches underneath her thirty feet of length overall. As a result, she was ruled more by her sails than her keel, making her a bit “tippy.” With all sails flying she often sailed “on her ear,” as sailors say—with her leeward rail (the side that dips low when a boat heels, opposite the direction of the wind) awash or underwater. And because, like most old boats and old people, she didn’t fit together quite as sleekly as when she was new, when she sailed in this fashion Prodigal leaked at her seams. A widening gap of open space in the connection between her decks and her hull—the two solid, molded forms of fiberglass by which she was constructed—siphoned seawater into the hull, especially during periods of high wind and seas, when the rails were awash.

On the passage to Ireland, a second storm late at night caught me by surprise. I was flying too much sail when it hit. Ideally a sailor sees a storm coming and reduces sail-area ahead of time to give the wind a smaller target and steady the motion of the boat. Not this time. This was just before the advent of GPS devices that now deliver inexpensive, accurate satellite weather forecasts to sailors in remote parts of any ocean. I was relying on friends sitting at their computers at home to text me the weather forecast for my location. A buddy in Washington State who fancied himself something of a weather guru had sent me the happy and mistaken news, that night, that I could sleep well in gentle, fifteen-knot breezes. I should have trusted my instincts to the contrary. Near midnight, the sea became as smooth as glass, and there wasn’t even enough wind to hold a heading. This was the proverbial calm before the storm. Sudden changes in wind speed almost always signal a weather system that is reorganizing itself for a dramatic change in direction and strength. So it was that night.

Once the front hit, everything in my world was suddenly tight, sideways, drenching wet, pitch black, and plunging up and down like a demon. I was flying the large, full mainsail (the one in the middle) and the working jib (the one in the front)—not the mizzen (the one in the back). I might have dropped the main and raised the mizzen to “split” the sail plan and steady the boat, but the conditions were just short enough of worrisome to give me pause before doing so. In strong winds and pitching seas, standing on the cabin top to release a large mainsail, then trying to get it all down, folded, tied and sorted, is like trying to rope a wild, frightened steer. The operation comes with its own set of risks that have to be balanced against the risk of doing nothing. The violent motion of a small boat getting bucked in the waves and the difficulty of keeping your feet underneath you, in the dark, on heaving, wet and slippery decks without hitting your head or breaking a limb, threaten to take the problem of a merely uncomfortable angle of heel and turn it into something exponentially worse. With no one to man the helm but a mechanical wind vane that needs sails and forward motion to work, there is the added problem, once the mainsail is struck or slacked and the boat looses steerageway, of keeping the boat headed into the waves and not turning sideways into a trough in the waves, where it can toss about and broach violently while you attempt to raise the next sail and get the steering back on track. I have done all of this before, many times, and too often not elegantly or well. It resembles a bull ride with the risk of getting thrown somewhere from whence you cannot simply pick yourself up and dust yourself off.

I knew it would be an uncomfortable night—in fact I slept lying mostly sideways against the inside of the hull that night in the forward berth—but I also knew the boat was never in danger of capsizing. I have sailed in many storms, and their bark is almost always worse than their bite. This was a blustery frontal system, not an organized major storm. I had supreme and well-founded confidence that Prodigal would shoulder the load and weather the conditions even with her mainsail fully unfurled, and she did.

But what I saw on the morning light gave me greater pause. With only manual pumping every few hours to stem the inflow of water, the rate and volume of water entering the boat through the hull to deck seam had increased dramatically. My feet touched down from the forward sleeping berth onto the cabin floor that morning into water sloshing over my ankles that covered the entire cabin and was rising into the forward bow section. The wind and seas were in no more or less foul a mood, but suddenly I was rapidly losing confidence in my vessel and the wisdom of the voyage. A few minutes of nervous bailing seemed to make no difference. Indeed, the water seemed to be rising slowly, and the boat by this time no longer had her rail in the water to explain where a continued flow of water might be coming from. I looked for a seacock (a hole in the boat controlled with a valve that opens and shuts) that might have accidentally failed but found none.

The idea of another three weeks and 2,000 miles headed to Ireland in a boat leaking this badly filled me with dread. I quickly dispatched a short message to family and friends on Facebook that I was again taking on water more precipitously and looking for a cause. It was at this moment that Coast Guard contacted me again and offered—urged might be the better word—a rescue from a nearby ship, the State of Maine, a training vessel of the Maine Maritime Academy.

I made a decision at this point that I would roll over in my mind for months to come. The better decision at such moments is always an emotional one, not a financial one. Too many sailors have gone to their doom chasing dollars into the abyss. I have been something of a minimalist since my first fevered readings of Thoreau and the Gospels, aided by the fact that I have made enough money from the comfortable ramparts of a law practice to be neither greatly impressed with what money can do nor greatly worried about my ability to get more of it. I never lived in terror of losing things or despair to hang onto them. The real wealth and fortune in life is time and freedom, which makes the free man in forma pauperis the wealthiest and most fortunate person in any room. I was always much more impressed by people who made the most out of their time and wasted the least of it than those who made the most of their wealth and spent the majority of it. The really poor bastards, it always seemed to me, were the ones who traded their years of health and vigor for the diminishing returns of business or profession or career that were destined finally to vanish without a trace in the memory of the world. In the end we have each other and such of our integrity as we have been able to preserve, and that is all.

On the sea that day, I had an estranged wife beckoning me to return to work on my marriage, and while I had been willing to defer that work to achieve the lofty aim, once begun, of sailing alone to Ireland, suddenly the idea of risking life and limb to go bailing my weary way into some God-forsaken shipyard in frozen Newfoundland, all so that after paying handsome storage fees for two or three or five years’ time I might find a cod fisherman gullible enough to take Prodigal off my hands for a few farthings, seemed far less noble. This makes no sense, I know, to the man who will walk two miles past one shop to save three cents on a foot of pipe at the next, but I have never wanted to be that man. He is welcome to his bargain. I am content with mine.

Which is why I took the offer, stepped off of my leaking boat, and said goodbye. The crew of the 248-foot ship State of Maine, manned by some hundreds of eager, fresh-faced midshipmen and their instructors on passage from Spain, executed their first-ever rescue at sea that day. Three days later, TV crews and newspaper reporters greeted me at the docks in Portland, eager to record the story that England’s Daily Mail cheekily called “stranger than fiction,” about an American novelist who had lost his yacht but saved his marriage.

It was a lovely story while it lasted, which is to say through three weeks of local TV news interviews and an AP story picked up around the world, but in the end I would lose boat and marriage, stem to stern, the hull and the rigging, the having and the holding—all gone. Susan asked for a divorce; I relented, and I left.

I suddenly had no ship and seemingly no purpose. Having recently sold my practice and retired from the law to make way for the obscure life of an unsung novelist, I also had no clients and no job. My children were grown, educated, and sorted in their own careers and faraway cities and relationships. For the first time in my life I had nothing to do and nowhere to go. So I sold everything I owned and took the first plane to nowhere.

This is the first chapter of a coming book to include the Voyage of Nevermore.

The post Letters from the Sea: A Sinking appeared first on Michael Hurley.

April 7, 2017

The Crossing

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle“What a long, strange trip it’s been.” –The Grateful Dead

Well, better late than never, as they say. It took me a while—fifty-nine years, to be exact—but after a lifetime of sailing, more than my share of lost and sunken boats, two lost and sunken marriages, and the usual coming and going of storms both material and ethereal that all of us must face, I finally crossed an ocean and made it to the other side, still standing aboard the same vessel I set out upon. If I were to say nothing else about it, a simple “hurrah!” would suffice to convey much of what I feel. I have witnessed, from a small and fragile arc, something of awesome expanse and power of the Earth that few people ever know. I have sailed literally in the wake of Columbus, known some of the same fears, watched the same mysteries unfold, by the same means and methods. It is good to be alive.

But there is more to it than that—much more. For starters, I now realize just how dramatically the world has changed since I first pointed the bow of a sailboat toward the horizon, as a boy. I recall an old photograph I snapped of my high school girlfriend against the backdrop of Annapolis Harbor in 1975. Years after I stopped gazing at the girl in the photo, I noticed that among the great array of sailboats moored in the harbor behind her there were none larger than thirty feet from end to end. In Annapolis Harbor today, and certainly in the Caribbean where I am now, there are scarcely any boats under forty feet, and the great majority are closer to fifty feet. More than a few are massively larger. They are all fabulously expensive and new and posh—save one. That would be my boat.

The Nevermore is a 1967 Camper Nicholson 32—a heavy, traditional, full keel sloop built in England and famous in her day for being one of the few pleasure craft built to Lloyds Shipping specifications, a stringent and expensive regimen of construction inspections and standards usually reserved for commercial vessels. The company traces its history of building some of Britain’s greatest ships back to the Napoleonic Wars. Fully eight of the few hundred Nicholson 32s that were built in the 1960s have sailed around the world. One of them, in January 2017, took me and an intrepid novitiate—fifty-five-year-old Londoner Jillian Gormley—across the Atlantic from East to West.

Nevermore came to me, like many of the good things in life, in the nick of time and rather unexpectedly. In the wake of losing another boat, a worthy but wounded thirty-foot ketch named Prodigal, on a failed attempt to cross the Atlantic solo from America to Ireland in June 2015, I sold everything I owned and made my way to Dublin by plane. From there I wandered for a few days on foot across a small patch of Ireland, then for two months and five hundred miles along the northern border of France and Spain on the “Camino a Santiago de Compostela,” the ancient pilgrimage route known as the Way of St. James. While walking the Camino I convinced myself that my sailing days were well and truly over, and that seemed no cause for sadness as I gazed upon the ageless glories of Galicia. But by the time I flew into London in October 2015, I faced a dilemma. Great Britain would allow me, as an American tourist, just six months to remain in the country; the rest of Europe, only ninety days more. I had no desire to head home. My holiday in Britain gave me just enough time to finish the novel, The Passage, that had been languishing half-finished on my laptop, but I needed a plan for what would come next. That plan was Nevermore.

As I often tell the uninitiated, a sailboat is not merely a means of conveyance or a pleasant hobby. It is a snug and safe and well-ordered home. It is a dream machine. It is a magic carpet, borne aloft by the power of imagination against the weight of despair, capable of flying to the remotest, most unlikely corners of all that is possible in life. Fighting against my own despair, I stood in a shipyard in Essex one cold, rainy day in February 2016 and imagined that a battered, unloved but unbowed vessel formerly known as Morica could live to sail and strive again, and that I could live to sail and strive again aboard her.

I wish (almost, but not really), I could tell you that the eighteen days I spent sailing alone from England to the Spanish island of La Palma, off the northwest coast of Africa, and the twenty-eight days Jillian and I spent sailing from La Palma to the West Indies—more than five thousand miles in all—were fraught with danger, drama, and death-defying feats of bravado. Not hardly. To be sure, there were difficulties. Nevermore, like her captain, is an old vessel. She has her idiosyncrasies and more than a few quirks—like the navigation lights that shorted off of Omaha Beach, near Normandy, filling the forward cabin with thick smoke and turning us into a pirate ship, ghosting two thousand miles down the coast of Portugal, every night, in near total darkness. A gale hit us on the first night of the Atlantic crossing, overpowering our self-steering and shaking the rigging so hard that the radar reflector flew off the backstay and crashed to the deck in a shattered mess. We lost our engine a week later, then our navigation lights (again). By the end, the only thing lighting up the boat at night was an eight-dollar solar-powered garden spotlight that I bought in a London hardware store on a whim, before we left. We hooked and ate a delicious mahi-mahi in the first week, but a week later an eight-foot marlin ate our hook and quickly left the scene with our blessing and 300 yards of fifty pound test line that it snapped like a thread. There were four more continuous, uncomfortable days of gales and twelve foot seas, midway, that made us wonder aloud what we ever thought would be “fun” about crossing an ocean.

But that’s the thing, you see. It was fun. Seriously uncomfortable, at times, but great fun nonetheless—made so not leastly by a sailing companion who was cheerful in all weathers and never uttered a discouraging word—not one—and a boat that never stumbled or strayed from her objective—not once. We would do it again, and we just might. But for now, I have more important things to do. As I type these words, I am bathed in balmy breezes, surrounded by tropical birds in the air and tropical fish swimming at my feet, listening to the lapping of clear, blue-green water and the whoosh of coconut palms high overhead. It has been two months to the day since we made landfall. I have a suntan but no watch on my arm—the battery ran out a month ago, and I can’t be bothered to replace it. I can’t really remember what day or even what time it is. All I know is that the sun is warm, that my boat is nodding at a mooring in a charming little nook known as Marigot Bay on the island of St. Lucia, and that the waitress has promised to bring me another Piton, soon. I am sitting on the water’s edge in a restaurant named Dolittle’s—so called because, as it turns out, this bay is where the movie based on the famous book about Dr. Dolittle was filmed. I am filled with newfound peace and newfound confidence. I have crossed a great ocean in a small boat and seen the wonders of the world. Talking to animals? Sure. Why not? Anything is possible.

But that’s the thing, you see. It was fun. Seriously uncomfortable, at times, but great fun nonetheless—made so not leastly by a sailing companion who was cheerful in all weathers and never uttered a discouraging word—not one—and a boat that never stumbled or strayed from her objective—not once. We would do it again, and we just might. But for now, I have more important things to do. As I type these words, I am bathed in balmy breezes, surrounded by tropical birds in the air and tropical fish swimming at my feet, listening to the lapping of clear, blue-green water and the whoosh of coconut palms high overhead. It has been two months to the day since we made landfall. I have a suntan but no watch on my arm—the battery ran out a month ago, and I can’t be bothered to replace it. I can’t really remember what day or even what time it is. All I know is that the sun is warm, that my boat is nodding at a mooring in a charming little nook known as Marigot Bay on the island of St. Lucia, and that the waitress has promised to bring me another Piton, soon. I am sitting on the water’s edge in a restaurant named Dolittle’s—so called because, as it turns out, this bay is where the movie based on the famous book about Dr. Dolittle was filmed. I am filled with newfound peace and newfound confidence. I have crossed a great ocean in a small boat and seen the wonders of the world. Talking to animals? Sure. Why not? Anything is possible.

The post The Crossing appeared first on Michael Hurley.

December 16, 2016

Bligh’s Revenge

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleMost people have heard of the mutiny on the Bounty. Even though the actual events occurred in the year 1789, the drama is just perfect for the silver screen, which explains why no fewer than four movies have been made about it. All the elements Hollywood could wish for are there: sunny, palm-shaded islands on the far side of the world; credulous, naked Tahitian women; homesick, pasty-faced British sailors who decide (surprise!) they would sooner betray king and country than give up all that to return to the squeamish, straitlaced sweethearts waiting for them at home.

But for all its prurient allure, the story of those gullible sailors and their fetching paramours is not nearly as compelling as the one told by the guy who was set adrift. With no charts, no sextant, and only a five-day supply of food and water, Captain William Bligh navigated a wave-swamped, twenty-three-foot open lifeboat loaded to the gunwales with eighteen men, over 3,600 stormy miles of the Pacific, landing safely forty-seven days later in Timor. In statute (land) miles, that’s the equivalent of drifting from New York to Los Angeles and back to St. Louis. It was nothing short of a miracle, and it remains to this day the greatest feat of navigation and survival at sea in the history of the British Royal Navy.