Michael Hurley's Blog, page 2

September 4, 2016

Pilgrim’s Progress

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

The Way of Saint James in Spain.

It has been a little more than a year, now. I remember well the day. It was filled with the kind of eruptions seemingly about nothing in particular that, in a marriage, are too often the harbingers of something very particular. Such arguments always seem random and senseless at the time. Only in hindsight do we recognize them as volcanic, arising from deep, unseen fissures that open slowly as a relationship comes apart. They may lie dormant for a while, but eventually they widen and explode. A critical eruption in my life came at ten o’clock in the evening of July 17, 2015, when my wife of five years asked for a divorce. I lacked the will to fight. The truth be told, I felt a strange mixture of fear and relief that she had spoken out loud what we’d both been thinking.

It was not the first time. There had been tremors before. We had separated the previous May, then had a change of heart in June. Now, the pendulum had swung back. I felt a sense of defeat, of inevitability.

Divorce, that always inopportune change of life, happened at an especially inopportune time for me. Six weeks earlier, I had been rescued five hundred miles south of Nova Scotia in the Atlantic Ocean after my thirty-foot sloop started taking on water from structural damage. Offered rescue by a passing ship, I made the decision to abandon my boat and my quest to sail solo to Ireland, where my wife and I had planned to reunite and, however naïvely, renew our vows. A week later I returned to Charleston amid some modest fanfare from an AP story about the rescue, but deep down I was still adrift. I was embarrassed about how the voyage had ended. I felt a little foolish and more than a little sad. I had failed. Six months earlier, the world had looked much brighter.

On January 1, 2015, I had sold my North Carolina law practice to a large firm, found a home for my employees, and, at the age of 56, walked away from a satisfying, thirty-year career as a trial lawyer. I wasn’t rich, but I was excited and animated by the new possibilities for my life, which is a feeling money can’t buy. My wife had taken a big job for a six-figure salary in her home town and moved back ahead of me to the lovely house where she had lived before we married. Selling my practice in Raleigh made it possible for me to join her. My children were out of college, away from home, and happily employed. I felt the pressure of professional life and the burden of being the primary breadwinner subside for the first time in three decades. I had high hopes for a more fulfilling future as a part-time novelist and a full-time English teacher. I took and passed my teaching certification exams, but my job-search sputtered. After applying to dozens of schools in the spring of 2015, the door to full-time employment remained shut.

The fall semester promised new opportunities for employment in teaching, but in the meantime, I looked forward to my first summer off in forty years. I owned an old sailboat, and the sea beckoned. A solo passage to Ireland offered a grand adventure and some publicity for my third novel, then in progress. The two months I planned to take to complete the voyage would fulfill the sea-time requirement to renew the commercial captain’s license I had acquired in 1992—handy, we thought, for a possible future venture running weekend charters. Even better, the marina rates in Ireland were half the cost of berthing a boat in Charleston Harbor. Better still, the savings on slip rent meant we could keep the boat as a second home in Europe and afford romantic getaways as we’d done before in the Bahamas and the Dominican Republic. But all those dreams slipped beneath the waves when Prodigal was lost. Six weeks after I returned from that disastrous passage, my marriage had foundered and sunk as well—my second marriage, mind you. I was embarrassed. I felt foolish. I had failed—again.

On that night of July 17, the new reality of my life was defined by everything that was missing from it: I had no job, no title, no staff, no office to go to every morning, no reason to put on a smart suit and tie, no clients clamoring for my advice, no house, no home, no boat—and, suddenly, no wife and no plan. There was very little left of the identity I had created for myself over the past forty years. Everything had changed, and so I made a decision to change everything.

Over the course of the next three weeks, I sold all that I owned—that is, whatever I didn’t absolutely need that anyone would buy, which was nearly all of it: a car, a truck, a grand piano, a canoe, a pop-up camper, toys and gear and equipment and computers and books and artwork and jewelry and knickknacks of all descriptions. The rest I gave away or left behind. At the same time, I began buying the tools of a pilgrim: a backpack, good boots, a sleeping bag, rain gear. Most importantly, I bought a plane ticket—to Dublin.

With nowhere in particular to go, I decided to go to Ireland, the land of my lately disappointed dreams, and wander awhile. I needed to live frugally, that much was clear, but I wasn’t about to surrender to fear over money, slink back to Raleigh, tail tucked between my legs, and resume the practice of law. I was in reasonably good shape, physically. Backpacking across Europe was something I had always regretted not doing after college and had never thereafter had the means or time to do. The liberation and excitement of simplifying my life and embarking on a new adventure obscured, for a time, the sadness of what was prompting those changes. I flew to Ireland on August 11 and set out on the Wicklow Way, a hiking trail through the rolling hills south of Dublin.

The first night, I was caught unawares by a feeling of abject loneliness in the small bivouac I had pitched in an unnamed wood. On the second day, still resolute, I chanced to meet four women who cheered me with stories of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela, the “Way of Saint James,” an ancient footpath travelled by pilgrims for a thousand years to the shrine of the apostle in Spain. If I ever wanted to go, they explained, I needed only to take a cheap flight from Dublin to Biarritz, and from there a train to St. Jean Pied de Port, in France, where the pilgrimage begins. They wished me well and left me alone again with my thoughts.

By the morning of the third day, despair had set in along with the stark reality that I had lost much of what I had once known as “my life.” I was overwhelmed. Starved for sleep, I found myself literally without the physical strength to climb the modest hill that loomed before me. I turned back, found a bed and breakfast with an Internet connection, and hastily wrote an email to my wife with a subject line that read, “Please Take Me Back.” I also wrote to friends, whom I had left with the glib and false impression that I was happily resolved to return to the single life, and admitted that I felt very much at the end of my rope. I needed rescue, but rescue came in an unexpected form. My wife answered my plea with a simple but firm refusal. In the end it would be her greatest gift to me: the gift of finality and clarity from which come healing and acceptance. There was no going back, this time. The only way left to me was the way forward.

It was then I vaguely recalled the sparse details of my conversation with the four women. Over the next twenty-four hours, I winnowed my possessions further—some thirty pounds’ worth. My bed-and-breakfast hosts became the startled recipients of various items of camping gear I wouldn’t need or couldn’t bear to carry on the 530 miles of the Camino. I shipped a laptop and cameras and cables and hard drives back to friends in the USA and boarded a plane. I had no guidebook. In fact, I barely knew where or what the Camino was. I relied heavily on the vague advice that all would be clear once I arrived in St. Jean. It was not.

The people at the help desk in the Biarritz airport spoke only French, not English or Spanish. Through a series of pantomimes, a pleasant woman explained that I was to walk outside to the curb and wait for the bus to Bayonne. In Bayonne I had my first meal in a French café, then more pantomimes with other pleasant people revealed that I was to take a second bus from there to St. Jean. By then I had joined a small knot of anxious pilgrims, all making our way for the first time to the same strange place. The volunteers staffing the tiny office set up in St. Jean spoke very little English but could not have been more caring. When it became clear that every albergue (hostel) in the village was full, they led me and twenty other late-arrivers to a gymnasium to spend the night in our sleeping bags on wrestling mats.

On the first morning of the Camino, I lacked a key bit of information. I had no idea which way to go. I learned then the most valuable lessons of life as a pilgrim: humility and patience. I didn’t know everything anymore. In fact, I didn’t know much of anything. I was dependent on others. I needed their help, and I needed to be willing to wait for it. I had to follow and trust people other than myself. And I did.

Through the happenstance and serendipity by which friendships are so often made on the Camino, I made new friends every day. We shared directions, advice, bandages, hopes, fears, sorrows, and stories. For so little money, I enjoyed simple and delicious meals and good wine. I savored, even more than the tapas, long hours of conversation with pilgrims from Australia, Malaysia, Germany, England, Ireland, Spain, Belgium, Russia, Norway, Poland, Italy, Denmark, France, Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, Slovakia, and a dozen other countries I can’t remember. Through it all, for two months and five hundred miles, I steadfastly refused to read a guidebook. Each day, I had no idea what lay ahead, how far I would go, when the next albergue would appear, or where I would find an open bed for the night. I simply walked and followed my fellow pilgrims. When I was thirsty, a village fountain would eventually appear, flowing with cool, clear water. When I was hungry, I would pass a café around a corner in a tiny village, its cases filled with food and its taps glistening with sweat from ice-cold San Miguel beer. New people and places and experiences and insights came to me when they were most needed, as if by the mystery of providence, every day. The Camino changed my life, and when I finally saw the giant botafumeiro soaring through the corridors of the cathedral in Santiago, my life changed again. Having failed at so much of late, I felt astonishing success when I reached the ocean at Finisterre. But my progress as a pilgrim didn’t end there.

Winter in the cottage near Machynlleth, Wales.

I was still on the Camino when I formed the plan come to Great Britain after I finished. I wanted a quiet place to hunker down for the winter and finish writing The Passage, which had been put on hold with all that followed the decision to divorce. A cottage on those lush, mist-soaked hills of Wales seemed the best, and importantly, most affordable choice. It was a brilliant choice at that. It rained every day in the little town of Machynlleth (pronounced “Mack-HUNK-leth” by the Welsh), forcing me to sit indoors and write. I was also befriended and encouraged by my landlord’s two cats, who sat on my desk while I toiled over my work, scowling disapproval whenever I left to warm myself by the wood stove, make another cup of the ubiquitous tea with milk, or fry up a bit of sausage and mash. When the clouds parted, I would dash out for a four-mile walk along the river into town in my newly acquired Wellie boots and wax coat—the essential livery of all Welsh travelers. Such shades of green as there are in the countryside of Wales I have seen nowhere else but the Emerald Isle, which shares much the same climate.

While my words marched across the page, time marched on as well. I felt a tinge of uneasiness born of the impermanence of my situation. As much as I enjoyed life as a lodger in other people’s homes, it hardly seemed a good arrangement for the long term. Moreover, I remained in Great Britain only at the pleasure of the government, which had given me a maximum of six months to enjoy the privilege. Although my grandfather was born in London in 1878, this afforded me, as an American, no special right to remain in the country of his birth. I had to get out by April 12, 2016, per the warning clearly stamped on my passport. I needed a plan. Once again I looked to the sea.

A well-found cruising sailboat is a many-splendored thing: a magic carpet, a snug and safe home in all weathers, a marvel of engineering, a figment of romance, a bearer of dreams. I should know. I have loved many of them and lost two of them at sea. Acquiring a third seemed to tempt fate, but I had safely called fate’s bluff when I left America. I knew the sailing life as well as I knew any life outside a courtroom. I warmed to the idea of another boat, but it would have to be a modest vessel at a modest price. There are many such boats, forgotten and unloved, with good bones and strong hearts, languishing in the marinas of the world. It was just a matter of finding the right one.

Nevermore in La Palma.

My search for the particular magic carpet that would carry me away started in November 2015 and took me along Britain’s remarkable railway system to Plymouth, on the southern coast, Walton-on-Naze, in the East, and Pwllheli (pronounced “Pull-HELLY”) in northern Wales. But these travels revealed no suitable vessel for my adventure. I despaired of the sailing plan altogether and considered finding new lodging for the spring and summer elsewhere, but before long an old British-built boat—one of the famed Nicholson 32s by Camper-Nicholson–caught my eye. There reportedly are more people who have flown in outer space than have circumnavigated in small sailboats, but no fewer than eight Nicholson 32s have circled the globe. The great number of them still available on the used boat market in Britain and elsewhere is testament to their sound construction.

I moved from Wales to London in January, continued to toil away at The Passage, and in February purchased the 1967 Nicholson 32 that I renamed Nevermore, borrowing from Poe’s famous poem, The Raven. My reasons were not as macabre as Poe’s. The name for me signified that this was my last chance. There would never be another boat, another time, or another hope for the sailing adventure of my dreams. She would not only be my home. I resolved to take her around the world. When all was ready, I sailed into the English Channel at Calais, bound for the Canary Islands.

The passage to the island of La Palma spanned eighteen days and a total of 2,215 miles for an average speed of a little more than five miles per hour—my longest and most successful nonstop ocean passage to-date. Most of that time was spent hundreds of miles out to sea, but for two days a southwest gale forced me close to the northwestern tip of Spain. I sailed within twenty miles of the cliffs of Finisterre, where I had finished the Camino seven months earlier and sat wondering where life might take me next. Then, I had never dreamed it would take me once again to sea, much less to the very patch of ocean before my eyes. After the disaster that had befallen Prodigal the year before, seeing the volcanic peak of La Palma rise 8,000 feet on the horizon on the morning of May 23, 2016, after eighteen days alone at sea, was not just a thrill. It was a requiem for all that I had lost.

As I write these words, I am enjoying life back in London while Nevermore tugs at her dock lines in La Palma. The next passage, 3,100 miles nonstop across the Atlantic to St. Lucia, looms large in my imagination. Hurricane season must pass first, but it will pass. If all goes as planned, I will board a plane for La Palma in December, and Nevermore will sail again in January. It is already September, but there is yet a little time to savor the past and ponder the vast unknown that has become my future—a pilgrimage to my own dreams. Yet as ethereal as dreams can be, today the ground feels surprisingly firm under my feet.

When I finished the Camino and arrived in Finisterre—a village whose name means literally “the end of the earth”—it seemed I had nowhere else to go. The eruptions that had ended my marriage and thrown my feet upon the Way of St. James had been violent and transformative. As if to underscore the all-too-real fact that I had been pushed to the brink—to the end of my rope, as I described it at the time—I had followed the pilgrim way to that most final of all ending places, where lost souls seeking absolution had for centuries literally chased God into the sea. But as I would come to learn, that place and that time was not the end—not the end of the world, or my life, or of me.

The strange and wonderful truth about volcanoes is that, for all their destructiveness, they are the only things on Earth that can actually create something new under the sun. While climbing the summit in La Palma last June, I heard hikers remark that there are acres of land formed by volcanic eruptions on the island that are only fifty years old. Imagine that. After four billion years, the Earth is still erupting and reinventing itself. Why should we be any different?

The view from the rim of the volcano on La Palma.

In the year since I wept in a nameless wood as a friendless foreigner on Irish soil, much of the chaff in my life has been burned away. All of my clothes now fit in a small carry-on bag, and I still feel like I have too much. Everything else I own, including the boat on which I will live and travel, fits into a thirty-two by nine-foot space. I have developed a visceral aversion to shopping and the acquisition of “things.” I want for nothing—not because I have so much, but because the things I value are so few and mostly free. I earn a pittance from my novels, but I owe no one a dime. Yet for all I have lost, whole new vistas have appeared as if by magic before my eyes.

There are people in countries all over the world—fellow pilgrims I met along the Way of St. James—who know my name and share a special part of my memories, who wish me well and carry my good will in return. They follow my progress through life as I follow theirs. There are people here in London and all across England and Wales who think of me, worry about me, love and care for me. These are souls who were unknown to me and I to them before the eruptions in my life cast me out into the void. They softened my fall. They are as new soil under my feet, the firm ground upon which I travel. “Leap,” John Burroughs wrote, “and the net will appear.” How very true. If only we could so believe, what a solid footing, and a loving embrace, we would find.

The post Pilgrim’s Progress appeared first on Michael Hurley.

May 4, 2016

Au Revoir

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

Michael Hurley aboard Nevermore in Calais, France, May 2, 2016.

The French have a wonderful way of saying goodbye that seems appropriate for the start of a sailing voyage. It’s not goodbye at all but rather, “until we meet again.”

I write these words late at night in a café in Calais whose lovely and charming wait staff have suffered gladly the use of their facilities and Internet connection long after my moules mariniere were a happy memory. (To be fair, everything French girls say sounds lovely and charming to me.) The Nevermore lies contentedly in the well-protected Calais marina, where the showers are hot and the bathrooms cleaner than those in any home I have ever owned. The harbormaster, Etienne, made sure I was looked after and insisted there was no rush to leave. But leave I must, tomorrow morning, with the tide. The weather and the wind are too perfect not to go. Everything is ready, and so am I. Once again, I recite the words of the classic Richard Hovey poem, “The Sea Gipsy”:

I am fevered with the sunset,

I am fretful with the bay,

For the wander-thirst is on me

And my soul is in Cathay.

There’s a schooner in the offing,

With her topsails shot with fire,

And my heart has gone aboard her

For the Islands of Desire.

I must forth again tomorrow!

With the sunset I must be

Hull down on the trail of rapture

In the wonder of the sea.

The island of my desire is a tiny volcanic eruption named La Palma, in the Canary Islands, exactly 1660 nautical miles from the end of the pier at Calais. From that starting point, I will execute the first of three complicated navigational maneuvers to make my landfall: two lefts and a right.

So it is goodbye at last to Paris, and to Calais, and to France, the country where I have been a happy if accidental resident for more than a month, beginning with a well-intentioned trip to comply with the six-month limit on my British tourist visa, followed by an unintended extension of that trip when Britain decided they’d had just about enough of me and my filthy American money—or, as comedian Stuart Lee might have put it, “comin’ over here, buyin’ the boats we’re tryin’ to sell, puttin’ our trades people to work, not usin’ a penny of taxpayer money, and obeyin’ the law.”

But enough bitterness, even if it is good fun to tease our stoic British allies. Much is right with the world. I have at long last a good ship and “a star to steer her by.” I have kind friends, a loving family, a new novel in the offing, fresh air in my lungs, and a spring in my step. All this and “the wonder of the sea.” What more could any man want?

The post Au Revoir appeared first on Michael Hurley.

April 25, 2016

Down the Rabbit Hole with Border Control

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

The sloop Nevermore awaits her lost captain in Burnham-on-Crouch, England.

Well, it’s official. Queen Elizabeth and I have finally come to a parting of the ways. And so it seems only fitting at this time to say farewell and look back at my six-month sojourn in that “green and pleasant land” of my grandfather’s birth. An essay about what I learned of life in England and Wales during my time there is soon to follow. But first, a bit of background and some well-earned grousing about the manner of my leaving:

Those who have followed my Tale of Woe are aware that, after coming to England last fall on a winter sabbatical to complete my third novel (which I happily did), I got the wild hare to buy yet another yacht and sail it around the world. This plan was all well and good, the only problem being that the six months of leave expressly granted to me as a tourist to remain in the UK (as clearly stamped on my passport) was due to expire on April 12, whereas some very necessary repair and refurbishing of the vessel by a British boatyard was not due to be completed until the end of April. Moreover, the season during which it is considered safe to cross the often treacherous Bay of Biscay on the way to the Canary Islands—my first port of call—does not begin, in the eyes of sailors much more seasoned and expert in matters of weather than I, until May 1.

So, being a lawyer charged with the duty to obey, not flout the law, I did what no normal person in his right mind would do: I dutifully left the UK on March 31 to come to France for a one-week holiday, then presented myself with my passport again at the border on April 7 with a polite request to re-enter the country and remain there, legally, for the few weeks necessary to pick up my new boat and go. I did this rather than simply overstay my visa by a piddling few weeks during which British authorities would have been neither interested in my affairs nor any the wiser about them. As proof of my bona fides, I presented to the UK Border Control officer at the Gare du Nord train station in Paris the bill of sale for the boat and a letter from the British yard stating that I had hired them to perform repairs expected to be completed by May 1 for my departure from the country on a passage to the Canary Islands at that time. On the form presented to Border Control, I asked for leave to return to the UK for up to two months, through June 7, in the unlikely event repairs took a little longer than expected or weather did not permit a departure precisely on May 1. This nefarious conduct of mine, I was to come to learn, is what passes for criminal intent in the eagle eyes of the British Border Control.

After being removed from the queue of passengers waiting for the Eurostar train bound for London, I was taken to an interrogation room where I was asked, in that decidedly suspicious and accusatory tone unique to law enforcement officials, a series of questions about my “activities” in the United Kingdom for the past six months—questions about where I had lived, the people with whom I had associated, whether I had ever sought to use the National Health System, how I had supported myself, and why I had not returned to the United States in all that time. I answered these questions politely and truthfully, to wit: that I had lived as both a renter and a guest in private homes and hostels in London and Wales, spent that time writing a novel, had not taken a job or a dime of the British taxpayers’ money, and was supporting myself from my own savings on a well-deserved world tour after a thirty-two year career as an attorney licensed by two state bars before which I remain in good standing.

After my interrogation I was asked to present myself to French authorities who, at the direction of the UK border control guard, frisked me and ransacked my wallet and my luggage—presenting, with suspicious glances to the border guard, credit card receipts for the escargot I had eaten during my crime spree in Paris. One item retrieved from my wallet was a business card I recently had printed up in the humble expectation it might help me sell a book or two. “Michael Hurley, Author,” it said, with an email address, my website, and the UK number of a mobile phone I had purchased in London to be able to call friends and family from overseas inexpensively. With this “evidence,” I was to learn, the UK Border Control had discovered my secret plot.

I was informed that I was being “detained” under some unknown provision of British law, after which I was taken to a room where I was fingerprinted and presented with a written decision by the border control, to be placed on record under my passport number, that in the judgment of my interrogator I did not intend to leave the UK on a sailboat but rather to reside there permanently and illegally, for which purpose I had conceived the brilliant strategy of leaving the UK and coming to France, presenting myself to border control, and inviting them to discover my scheme.

An hour later I walked out of the Gare du Nord in a daze and found my way to a local hostel, where I have remained for the past three weeks—enjoying some extra time in Paris as best I can, under the circumstances, while trying to coordinate the logistics of a major ocean voyage by email and telephone. When the repairs to my boat are complete, a hired captain and crew will sail the boat across the English Channel to meet me in Calais. From there I will venture out into the busiest shipping lane in the world, alone, on a two-thousand mile passage aboard a boat I will have never had the opportunity to sail before, without setting foot again on British soil. May God help me.

And so it is surely with good reason we hear that the government of Great Britain is struggling to make ends meet, my friends. I would guess that several trainloads of indigent migrants looking to flail themselves onto the breast of that country’s social welfare system have passed through Gare du Nord undetected these past three weeks, while Border Control can boast of a perfect record in keeping American yachtsmen and the money they would seek to inject into the British economy safely away.

But as with every hurdle in life—and to be fair, this hardly qualifies as much of a hurdle at all—we learn something about ourselves and the world in which we live. For most of my adult life I have been safely ensconced in the American upper middle class, with an income that placed me in the top five percent of the population. I have a college degree and a law degree. My children went to private schools and expensive summer camps. I belonged to private country clubs and yacht clubs and took expensive skiing and sailing vacations, staying in high-priced hotels in places like Aspen, New York City, the Bahamas, and Martha’s Vineyard. Most of my friends were and are people just like me. I represented the interests of large corporations as a partner in a major law firm, and I have been responsible for a payroll employing many people who themselves were safely ensconced in the upper middle class. I have never been charged with a crime, and before I could qualify as a member of the bar in Texas and North Carolina I had to undergo an extensive investigation of my character by the FBI during which employers, friends, and neighbors going back to my teenage years were interviewed. So it was fairly laughable to me that a gate officer with the UK Border Control could reach the conclusion she did.

Except that she wasn’t laughing. And soon, neither was I.

It is a sobering and distressing thing not to be believed, not to be trusted—to have our honest and good intentions given the most sinister and unflattering interpretation possible. And yet this impoliteness is something that many who are not safely ensconced in the upper echelons of polite society experience every day and come to expect as normal. Until you experience it yourself in some small way and are unceremoniously lumped in with a segment of society with whom you would otherwise have almost nothing in common, it’s hard to understand how it must feel.

While (my British friends would say whilst) I was living in England and taking my time there for granted, I once watched a British TV show featuring real-life encounters with border control. Episodes showing foreigners being interrogated by crafty agents and thwarted in their attempts to illegally work in or enter the UK were offered as a form of entertainment to the British public. I found the show horrifying and remember thinking so at the time. The imbalance and abuse of power was stark. Here were mostly low-income, uneducated Eastern European migrants, some struggling with English, who were looking for a means to support themselves and their families, being not just questioned but fairly taunted and bullied by agents relishing their power and their superior command of the language and the situation. The lack of humility and compassion made me embarrassed for Britain. There was a kind of ugliness about it. I felt uneasy watching it, and so I turned it off. A few weeks ago in the Gare du Nord Station, this show was turned back on for me, and I found myself in a starring role.

We would do well to have more compassion for those who find themselves on the periphery of the safe places where most of us live our lives. Welcome to the stranger and compassion for the traveler are traditions and values sadly lost amid all the shouting about immigration and refugees and borders. One of the most memorable lessons of my travels as a pilgrim and a nomad across 500 miles of the Camino in Spain was a verse I read written on a wall in Castrojirez. It said, simply, that the great illusion of our time on Earth is the notion that “I am here, and you are there.” The truth is, we are all in this together, all waiting on the same border, all travelers eager for a better life, a bit of comfort, and a place called home.

The post Down the Rabbit Hole with Border Control appeared first on Michael Hurley.

April 24, 2016

Women’s Work: The American Cathedral in Paris

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

The American Cathedral in Paris

It was a glorious morning today at the American Cathedral in Paris, where the choral service at eleven brought back fond memories of my home church, Grace Cathedral, in Charleston. I had the distinct pleasure to hear the homily given by the dean of the cathedral, Lucinda Laird. Dean Laird is one of that rare breed of Episcopal priests in the vein of Nancy Allison and John Zahl who have a Calvinistic zeal for good preaching, and that was certainly in evidence this morning. Elaborating on the story in The Book of Acts, chapter 11, verses one through eighteen, she explained how revolutionary the idea was in the first century that the gospel should be given to non-Jews. In comparison, she noted her own astonishment as a member of the Episcopal Church at a time some decades ago, when women priests were still unknown, at seeing trailblazer Bea Blair raise the Eucharist during mass. Upon hearing a female priest say the words of the liturgy, “this is my body,” a young Lucinda Laird understood fully for the first time that that  sacrifice was indeed meant for her and her own flesh instead of as something one step removed in the body of a man.

sacrifice was indeed meant for her and her own flesh instead of as something one step removed in the body of a man.

It pains me somewhat to think that we are still in a place and time theologically in which female priests must so often speak of being female as black politicians speak of being black. No one, I am quite sure, is interested in my thoughts on being male. But lest we forget, not far from the altar of the American Cathedral in Paris where the Eucharist was celebrated today by two women priests of outstanding caliber, competence and holiness, stands another altar in the same place it has stood for over a thousand years, and yet at the altar of the Cathedral of Notre Dame, no woman is yet welcome to consecrate the host. So, therefore, the quest for understanding continues, but we are fortunate to have such guides for the journey as Lucinda Laird and many like her who remind us  what a gift much of the world is missing in the priestly wisdom of women.

what a gift much of the world is missing in the priestly wisdom of women.

The post Women’s Work: The American Cathedral in Paris appeared first on Michael Hurley.

April 21, 2016

The French Law of Pastry and Women

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

Paris, 20 April 2016, along the Boulevard de Hausmann

Somehow, I always knew it would be the French—that they would have the answers to the burning questions about life and love. And, of course, they do. As I sit alone here in Paris, that liveliest and loveliest of cities, this wisdom came to me in an unexpected, artistic, nuanced, metaphorical and, therefore, quintessentially French sort of way. I learned it through pastries.

Women and pastries are about choices. There are lots of them. They are rich and lovely and, taken in quantity, potentially very bad for you—fatal, to be sure, even if you do go in a rather pleasant, somnolent, and satisfied condition, rising on dust clouds of powdered sugar to heaven. But if you don’t wish to die or become disabled and no longer able to function you cannot have them all. You must choose.

The thing about pastries and women is that you cannot try before you buy—at least not without a lot of shouting and unhappiness and recrimination and demands for payment of damages. You must choose before you try and damn well not complain about your choice after you do, because there won’t be another. Herein enters the need for a method of choosing. Some criteria. On this score, French pastry chefs make your job as difficult as possible.

First of all, the selections are behind a glass case, where they cannot be touched or smelled but rather only admired from afar. You look. You lust. You dream of what lies within that glistening, creamy exterior. But you do not know. Not really. And the pastry chef, who is conspiring with the pastries to deceive you and who in any event is French and does not speak your language, has no interest in telling you. Even if he did, words would fail him, because the experience for good or ill is beyond description. And so you stand there, looking.

Your eyes are naturally drawn to the most spectacular, exquisitely rendered, and shiniest candidates. These seem precious to you. A perfectly round lemon tart catches your eye. She is so very yellow, and the flourish of dark chocolate resting on top, in the middle, sets off her color magnificently. Her crust is even and unblemished. A shimmering glaze covers her filling. She calls to you from within her glass prison. You answer. “I’ll have that one, please,” you say.

Your eyes are naturally drawn to the most spectacular, exquisitely rendered, and shiniest candidates. These seem precious to you. A perfectly round lemon tart catches your eye. She is so very yellow, and the flourish of dark chocolate resting on top, in the middle, sets off her color magnificently. Her crust is even and unblemished. A shimmering glaze covers her filling. She calls to you from within her glass prison. You answer. “I’ll have that one, please,” you say.

You think you see a flicker in the pastry chef’s eye as he fills your order that suggests you haven’t chosen quite so as wisely as you might, but you are too busy arranging the particulars of payment and delivery to dwell on this. Then, before you know it, you cradle the prize within your trembling hands. But soon, you experience the first taste. Then and only then is the truth known, the lesson, clear.

You have not chosen wisely, my friend. The lemon tart, while iridescent and beautiful, is bitter to the taste, a bit dry, with a crust that is not quite so soft as you imagined, and filling that is less substantial than you’d hoped. You look longingly behind the glass at the large, rough, and pleasingly misshapen croissant bulging with a soft, creamy middle, and she looks forlornly back at you. “You might have chosen me and been happy,” she says, “but alas . . .”

And so you and the lemon tart walk on dejectedly together. You do not bother to finish her. There is not enough café au lait in all of France to help you choke down that stale crust. All your thoughts are for the plump croissant. But even if the lemon tart is bitter, you are not. For this is Paris, where longing of the heart is a celebrated, national agony, where absence makes the heart grow fonder, and where great symphonies and literature of legendary magnificence have been written of the beignet that got away.

And so you and the lemon tart walk on dejectedly together. You do not bother to finish her. There is not enough café au lait in all of France to help you choke down that stale crust. All your thoughts are for the plump croissant. But even if the lemon tart is bitter, you are not. For this is Paris, where longing of the heart is a celebrated, national agony, where absence makes the heart grow fonder, and where great symphonies and literature of legendary magnificence have been written of the beignet that got away.

The post The French Law of Pastry and Women appeared first on Michael Hurley.

April 20, 2016

A Few Thoughts Before The Voyage

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

Paris, 20 April 2016.

And so it begins. Another vessel. Another voyage. Another harbor. Another long-awaited, dreamed-of, hoped-for landfall. The old gnawing fear, once more. The old intelligence that always listens to fear for what counsel it may offer, met by the same understanding that fear is a junior officer not well suited for command. There is no help, no life, no answer, no hope but to make way, for forge ahead, to go at last to sea again.

Those who have never faced the ocean alone for days upon weeks in a small boat—faced the darkness, the mystery, the violence, the sheer power, the utter vastness, its pitiless yet beautiful indifference—have no clue. Giddy and well-meaning offers to “come along for the ride” are met with knowing and protective smiles. You do not want to be with me, friend, when the place we now know as “there” finally, chillingly, unalterably, becomes “here.” Here, there be dragons. Here, there be demons. Here, there be places within yourself to which you have never travelled and where you do not wish to go. Trust me. Rest peaceably in your easy chair, by the warm fire and the glow of the television set, dry and safe and filled with sweet foods and comforted by the purring of your cat and the loyalty of your dog and the caress of your lover. I do not take this way because I will. I take it because I must.

I have stepped up to safety from two vessels left battered and crippled at sea. There will not be a third. Not for nothing is the one on which I now sail named Nevermore. On this boat I will go around or I will go down, but there will be no going back. There is no other vessel, no other life, no other time, no other heading. This vow comes from the heart of a realist, not a hero or a martyr. I love my life and surely wish to keep it. Mine is no great valor. We all face the same fate unawares. None of us is long for this world. We are all sailing aboard the Nevermore.

The post A Few Thoughts Before The Voyage appeared first on Michael Hurley.

February 4, 2016

The Passage to Come

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle News from London, 4 February 2016 . . . It is finished! At exactly 2:20 p.m. today, I typed the last keystroke of my latest novel, The Passage. It is 94,626 words and 378 pages in all. For the sake of comparison, that’s roughly as long as The Hobbit (95,022 words) and twice as long as The Great Gatsby (47,094 words). Of course, if literary greatness were measured in ink, the Code of Federal Regulations would be in the New York Times top 10. The Passage is not a letter longer or shorter than it needed to be to tell the curious tale of Jay Danforth Fitzgerald and his stowaway . . .

News from London, 4 February 2016 . . . It is finished! At exactly 2:20 p.m. today, I typed the last keystroke of my latest novel, The Passage. It is 94,626 words and 378 pages in all. For the sake of comparison, that’s roughly as long as The Hobbit (95,022 words) and twice as long as The Great Gatsby (47,094 words). Of course, if literary greatness were measured in ink, the Code of Federal Regulations would be in the New York Times top 10. The Passage is not a letter longer or shorter than it needed to be to tell the curious tale of Jay Danforth Fitzgerald and his stowaway . . .

Needless to say, I am well past my deadline for the planned January 2016 release of this book. This delay I blame squarely on the intoxicating beauty of Wales. The manuscript now goes into the meat grinder of editing and production. It will be released through Ingram in hardcover in the Spring and available wherever books are sold. Stay tuned for details about the date, etc.

In other news, after rolling around Europe for the past six months, licking my wounds from the loss of the Prodigal, I have decided to stop feeling sorry for myself and get back on the horse that threw me. I have acquired a stout sailing vessel and named her the Nevermore, after Poe’s famous poem, for she is my last ship, my last hope for glory, and my last chance to achieve the dream of sailing alone around the world. There will never be another time, and there will never be another boat. She is a 1967 Camper Nicholson 32, built to Lloyds standards in England by a venerable shipyard with a history going back to the Napoleonic wars. (Her sister ship shown at sea in the photo above.) I am planning a May 2016 departure on a solo voyage around the world that will begin with a 2,000 mile passage from Brighton, on the south coast of England, to La Palma, a small volcanic island in the Canaries, off the coast of North Africa. The release of The Passage will be timed to coincide with the start of the voyage, hopefully with some publicity in the British press. I will have, as before, the ability to communicate with my friends on Facebook from aboard ship in route. I look forward to having all of you along on what promises to be the ride of a lifetime. Much more news, photos and updates to come in the months ahead!

February 28, 2015

Sir Francis Chichester and the Mind of the Solo Sailor

Send to Kindle

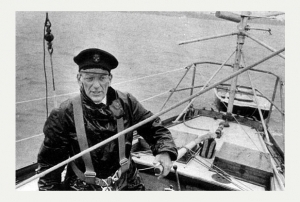

Send to Kindle On August 27, 1966, at sixty-five years of age, suffering from terminal lung cancer and unexplained palsy in one leg, Francis Chichester set out alone from Plymouth, England aboard Gipsy Moth, a 54-foot, custom-built ketch, bound for the South Atlantic. When he returned nine months, one day, and 29,630 miles later, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth for completing the fastest solo circumnavigation in history along the “clipper route,” by way of the southern capes. He made only one stop—in Sydney, Australia, for seven weeks. Before and after Sydney, he spent 107 and 157 consecutive days, respectively, alone at sea. He was dead of cancer within five years of this stunning achievement.

On August 27, 1966, at sixty-five years of age, suffering from terminal lung cancer and unexplained palsy in one leg, Francis Chichester set out alone from Plymouth, England aboard Gipsy Moth, a 54-foot, custom-built ketch, bound for the South Atlantic. When he returned nine months, one day, and 29,630 miles later, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth for completing the fastest solo circumnavigation in history along the “clipper route,” by way of the southern capes. He made only one stop—in Sydney, Australia, for seven weeks. Before and after Sydney, he spent 107 and 157 consecutive days, respectively, alone at sea. He was dead of cancer within five years of this stunning achievement.

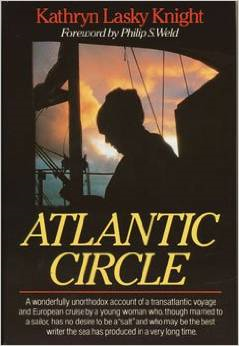

As a solo sailor myself, albeit one not worthy to untie Chichester’s Topsiders, I have long been fascinated by the pathos of single-handed sailing and the psychology of those who practice it over great distances. It’s not just that life is uncomfortable lived during sudden squalls or maddening calms or at a constant, 30-degree angle of heel for days on end. Because of its vast size, the ocean is paradoxically the world’s most effective isolation chamber. Kathryn Lasky, who crossed the Atlantic in company as a novice sailor in the seventies, wrote convincingly of this in her book, Atlantic Circle:

Fog blind, cold, and scared, I experienced a kind of sensory deprivation that I had never known. I had never in my life felt so totally cut off . . . The chasm grew between the world I had known . . . and the one I was now committed to. Things became abstract to me in a particularly threatening way . . . I wondered if I had ever smelled green grass . . . or met a best friend for lunch . . . Had there ever been a person like Shakespeare? . . . Had I ever actually read him?

Funny things happen to the mind “out there,” not to mention the weird mental reprogramming before and after a voyage that serves to allay our fear of the future and gild our memory of the past. I have experienced these phenomena myself, but solo sailing being what it is—solo—it is difficult to know how these phenomena manifest in others in order to understand whether one’s own experiences are “normal.” That understanding is brightly revealed in the fascinating book that Chichester wrote of his epic voyage, Gipsy Moth Circles the World (Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd, 1967). The book is no longer in print, but used copies are widely available. As I was reading mine during a cross-country train trip this winter, a fellow passenger in the dining car saw the cover and remarked that he had read the book in high school.

Chichester’s book is not light reading. It was compiled from more than 200,000 words of tediously thorough daily entries in the ship’s log. More scientific report than adventure drama, it goes into eye-crossing, repetitive detail about every conceivable minutia of shipboard routine. When his boat suffers a knockdown and stores spill out of the cabin lockers, we are told about the number and condition of each apple, orange and grapefruit as it is returned to its proper place. Yet it is Chichester’s faithfulness to detail that gives the reader an authentic and reliable look at the psychological toll of the voyage. Despite—or perhaps because of—Chichester’s staunchly British aversion to self-pity and emotional display, we can be certain that when he admits to having a less-than-stiff upper lip, we are reading something genuine and significant. From what his story has to teach us, I have distilled a few observations about the mind of the solo sailor for my own instruction.

“For what I fear comes upon me, And what I dread befalls me.” Job 3:25

I was struck by how often Chichester came to grief, in some irritating and unexpected way, and how many times his boat and gear utterly failed him. Reading about his maladies and missteps made my own seem picayune. Chichester’s woes were of Jobian proportions. I have excerpted, here, only a small fraction of the lamentations retold in his book:

Despite having crossed the Atlantic six times—three of them solo—before his circumnavigation, he often experienced seasickness and an associated lack of desire for food. His waist narrowed to a “ladylike” thirty inches. He didn’t begin to feel hungry again until five weeks into his circumnavigation. Even after he began to eat, he was still perennially seasick.

Due to the uncomfortable motion of the boat, he could not shave or wash for days at a time.

Within the first week, stress from the hull slamming into waves was so great that a structural bulkhead in the bow of the boat cracked and parted.

His spinnaker pole bent in half and jammed in the track on the mast.

Gipsy Moth IV, which was specially designed for speed and built for this trip, was unseaworthy and shabbily built. It could not hold a heading, and it heeled so easily–Chichester describes it as like “the flick of a cane”—that it heeled precipitously and broached often, dragging the ends of the main and mizzen booms in the waves. “The boat was too big, no doubt of it,” he writes.

The self-steering gear performed poorly, failed continually, and eventually packed up entirely. Without it, the boat was so poorly balanced that Chichester could not trim the sails to hold her on course. His despondency at this is palpable in the following excerpt: “The self-steering gear could not be repaired on board. I was well and truly in trouble . . . The Gipsy Moth IV could never be balanced to sail herself for more than a few minutes. . . The bald fact was that she could only be sailed from now on while I was at the helm, otherwise she must be hove to while I slept, cooked, ate, navigated, or did any of the many other jobs about the ship . . . I should do well to make good, on average, 50 miles per day.”

He suffered knockdowns and capsizes in the Southern Ocean in gale winds and forty-foot seas on multiple occasions.

He completely lost a sense of balance in his feet and had chronic pain and cramping in his right leg.

He lived for days at a time with a 20 to 40 degree angle of heel and “violent slamming” of the hull against the waves which he reports he “could not stand.”

He suffered what he describes as “appalling lethargy.” He writes that this “swamps” him, making “anything that required remembering and doing twice daily” seem like “a burden.”

The door to the head swung open unexpectedly and cut a two-inch bleeding gash on his forehead, leaving him “stunned.”

His winches seized from electrolysis, making it difficult to trim sails.

He chipped off two bone fragments in his elbow during a fall, causing severe swelling, decreased range of motion, and pain that plagued him constantly.

His alternator wouldn’t charge his batteries, so for a time he could not use electric lights in the cabin at night.

The wind always seemed to be blowing from wherever he needed to go.

The electric bilge pump curled up and died.

The boat leaked everywhere from breaking seas and rain, and often his sleeping bag and blankets were soaked through.

The boom vang tore a stanchion out of the deck during an accidental gybe.

He cracked a tooth when he bit into a piece of cake, tried unsuccessfully to “glue” the tooth back together, and eventually had to file the edges down.

The drogue (a kind of sea-parachute used to slow the motion of the boat for safety in heavy seas) disappeared overboard when the line holding it parted.

Exhausted but unable to rig the boat to steer herself in light winds, again and again he would drift off to sleep only to awaken hours later and discover all sails aback with the boat sailing well in the opposite direction, giving up all the hard-won miles of the day before.

On many occasions Chichester admits to feelings of despair—something I found fascinating and strangely encouraging, given who he was and what he was ultimately able to achieve. It is remarkable to see this icon of seagoing machismo not only acknowledge feelings of self-doubt and defeat but teach the reader, by example, how to cope with them. After a knockdown in the Tasman Sea on the first leg of the voyage, he writes:

I was fagged out, and I grew worried by fits of intense depression . . . I felt weak, thin, and somehow wasted, and I had a sense of immense space empty of any spiritual—what? I didn’t know. I knew only that it made for intense loneliness, and a feeling of hopelessness, as if faced with imminent doom.

Despite this setback, he made it safely to his planned midway stop at Sydney, Australia, where he reunited with his beloved Sheila and spent seven weeks recuperating, talking to the press, and refurbishing his boat. And yet, despite the strength he gained in surviving this ordeal, he suffered even deeper despair on the second leg of the voyage, when Gipsy Moth IV experienced another knockdown in the Southern Ocean on the way to Cape Horn:

I was faced with this awful mess; it looked like a good week’s work to clear up, sort and re-pack everything. I have rarely had less spirit in me. I longed to be back in Sydney Harbor, tied up to the jetty. I hated and dreaded the voyage ahead. Let’s face it; I was frightened and had a sick feeling of fear gnawing inside me.

Although he admits he had been “damn lucky,” he logs, “I could not be more depressed. Everything seems wrong about this voyage. I hate it and am frightened.”

These words from Chichester, telling us that he “hates” the voyage and “longs” to be in port, tied to a pier, seem so contrary to the sum and substance of the man we know as to make him unrecognizable. And yet anyone who has spent more than a few days at sea on a small boat, far from shore, will know exactly what he’s talking about. There was a time not too far removed from these emotions when Chichester did not hate the voyage but loved it and was consumed with passion for planning it. Experienced offshore sailors well know this kind of schizophrenia, too.

Although most of the world at the time glorified him as a stoic hero, Chichester writes of his ongoing struggle with loneliness. This hit him hardest in the Southern Ocean, where the seas and winds are of legendary proportions:

Another thing which I find hard to describe, even to put into words at all, was the spiritual loneliness of this empty quarter of the world. I had been used to the North Atlantic, fierce and sometimes awesome, yes, but the North Atlantic seems to have a spiritual atmosphere as if teeming with the spirits of the men who sailed and died there. Down here in the Southern Ocean it was a great void. I seemed planetary distances away from the rest of mankind.

. . . .

My sense of spiritual loneliness continued. This Southern Ocean was like no sea I had met before. It is difficult to paint the picture with words . . . I have sailed across the North Atlantic six times, three times alone, and experienced winds up to 100 miles per hour there, but looking back it seemed so safe compared with this . . . The Southern Ocean was totally different. The seas were fierce, vicious, frightening.

. . . .

After three months of solitude I felt that it was all too much; that I could not stand it, and could easily go mad with it. All this is weak nonsense, I know, but that is how I felt when I was twisting about in my bunk trying to clear my brain of all the thoughts and images attacking it.

As terrifying as his encounters were with apocalyptic storms and seas, it is remarkable to consider that Chichester regarded prolonged periods of total calm more wearying, both physically and mentally:

Calms were the devil, and sometimes it could feel quite creepy as I sat or lay alone in the cabin . . . Day after day I waited for a big wind switch . . .

. . . .

The near-calms were the most exhausting ordeals for me. Time after time the ship would go about, with all sails aback. I would have to wear around, and retrim the mainsail and mizzen. These near calms seemed to last seven or eight hours, and usually occurred at night. I would be up and down to the cockpit time after time for retrimming, and I would be lucky to get more than a couple of hours’ sleep during the night.

If there is one immutable piece of advice mere mortals can take away from Chichester’s ordeal and triumph, it must surely be to stay far, far away from the Southern Ocean, home to Cape Horn:

At last, I feel as though I am waking from a nightmare of sailing through that Southern Ocean. There is something nightmarishly frightening about those big breaking seas and screaming wind. They give a feeling of helplessness . . . and it all has ten times the impact when alone . . . . To be candid, I think that anyone who sails a yacht in the Forties [the 40th parallel of latitude near Antarctica] is a fool—but I knew that before I started.

“Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid.” John 14:27

As he gets closer to home, Chichester’s spirits rise with the latitude and the temperature: “It was wonderful to sit in the sun and spray on the foredeck, and I even tried to sing!” He also begins to cut himself some slack: “I just feel damned lazy, and enjoying the sail. Also enjoying a rest and leisure. What bliss to be in the cockpit with the sun and warm breeze on one’s skin, just watching the sea, and the sky, and the sails, and meditating! There are stacks of things waiting to be done, but I don’t want to do anything until I am forced to.” The final chapter, “A Pleasant Sail At Last,” captures this mood perfectly.

The kind of busy-ness of mind and pleasure in small tasks that is not possible when one is depressed and terrified overtakes his writing as he nears England. Although storms and mishaps continue, they scarcely break the rhythm of his growing sense of inevitable success. It’s worthwhile to watch, on YouTube, newsreel footage of his triumphant return amid a flotilla of welcoming boats and thousands of cheering supporters on land. The man who said he once “hated” his voyage, considered himself a fool for undertaking it, and with bitterness and fear wished his boat were tied to a pier safely in port, became a national hero for being and doing the opposite of all those things. And therein lies the first lesson of Chichester’s odyssey, which is the value of perseverance above all.

“With the ancient is wisdom, and in length of days, understanding.” Job 12:12

Chichester, the burnt edge of the British upper crust and the quintessential Anglican, was congenitally averse to prolonged self-examination. He shares no great epiphanies or deep spiritual conclusions from his nine months alone at sea. After slogging through 222 pages of text as dense as the London fog, the reader arrives at the end of the voyage and the book in this final paragraph, where Chichester unceremoniously reduces the entire odyssey to a matter of arithmetic:

Gipsy Moth had completed her passage home of 15,517 miles in 119 days, an average speed of 130 miles per day. The whole voyage of 29,630 miles had taken just nine months and one day from Plymouth to Plymouth of which the sailing time was 226 days. Perhaps I might add that, with eight log books filled up, I had also written more than 200,000 words. [The End.]

Yes, Sir Francis, perhaps you might have added that and a good deal more—like whether you felt the voyage was worth it, in the end, what you learned about yourself along the way, and how you managed to overcome your fear, depression, terror, and anxiety to find the will to finish. Although Chichester leaves us wondering all these questions, some of the answers are apparent from the story itself. Here are some tidbits of Chichester’s untold wisdom that I managed to divine:

You Are Not Special. Contrary to the mantra of 1970s pop psychology, Chichester did not see himself as a special person on whom the Heavens should be expected to shed everlasting light. He never succumbed to delusions of his own grandiosity. Conversely as a result, he did not perceive the injuries and setbacks he encountered as punishments administered by some malevolent and displeased, unseen power. I mention this not to challenge the Judeo-Christian orthodoxy that we are all special in God’s eyes. I intend only to acknowledge the fact of the matter, which is that a lot of God’s special people have come to inexplicable hardship, misery and death. Chichester’s refusal to interpret maladies as some sort of cosmic comeuppance for past sins freed his mind to cope with them and solve every problem in turn. He never sank into the despair that defeats those who believe the universe is either for them or against them, because he was too humble to presume that he was of great particular importance to the universe.

The Wind and the Waves are Not Out to Get You. The hills may be “alive with the sound of music,” but seawater is just so much hydrogen, oxygen, and sodium. Likewise, the wind is driven by temperature and pressure, not angelic tantrums. With the exception of the Southern Ocean below the 40th parallel, which clearly creeped him out and where as a consequence I will never go alone in a small boat, Chichester never anthropomorphized the seas or the storms. Breaking waves and high winds are terrifying enough for the damage they can do, but their havoc is random and indifferent and therefore survivable, not focused and deliberate.

The Sun Will Come Out Tomorrow. Okay, maybe this theorem didn’t originate with Chichester, but it was surely proved by him. “Fear doesn’t last,” he writes. I thought about that for a long time before realizing he was exactly right. Fear and euphoria are episodic emotions, not states of being. Recognizing when we are afraid that “this too shall pass” is a good way to help along the passing. Every night, every storm, and every gray sky is temporary. Remembering that the man who knelt beneath Queen Elizabeth’s sword at the end of his voyage was the same man who once “hated” the voyage and wished he’d never left brings home the value of perseverance.

You are not the Voyage; the Voyage is not You. There were many times, I gathered, when Chichester found it difficult to grasp this truth—including those times he recounts lying in his bunk and beating back the twin demons of self-doubt and self-loathing. Ultimately, however, he seemed to allow himself to detach from the setbacks and disappointments of a particular moment and “zoom out” to see the bigger picture of his life in a context larger than the nine months that comprised this particular voyage. It surely was not easy to do, as Kathryn Lasky discovered when, during an Atlantic crossing, she wondered at times whether she had ever lived a life other than the one inside the walls of her little ship. I think maintaining that perspective and sense of the scale of the events of one’s life, on a long ocean passage. is no less important than it would be to a prisoner of war or an inmate serving a long prison sentence. Remembering who we are and where we came from, and that there is a wide world beyond our own horizon and a future yet to be fulfilled, is key to surviving the hardships we are experiencing at the moment.

Busy Hands are Happy Hands. Chichester kept himself busy. In fact, reading about all the minute details of his daily tasks is exhausting for the reader. Unfortunately for him there was a lot going wrong that needed fixing, but even his daily bath and shave were elaborate undertakings. Meals were meticulously and deliberately prepared. The navigational log was faithfully attended. He rarely denied himself the nightly reward of a hot toddy. Sun sights with his sextant were dutifully recorded. Constantly checking his boat for areas of wear and chafe and keeping his living quarters orderly gave him a sense of purpose and a familiar routine to his day that seemed to carry him through.

Reading is Fundamental. Joshua Slocum, in writing about his epic circumnavigation in 1898, said people often asked him whether he was lonely “out there.” He was not, because he had all the great authors of history with him in the books he carried on board. I recall thinking, after a seventeen-day solo voyage to Bermuda and back in which I finished David Copperfield and Oliver Twist, that I had become next of kin to Charles Dickens. There is nothing like the imagination of a great writer to dispel the monotony of an unchanging sea. So it was with Chichester, and so it should be for all who would follow in his wake.

One Day at a Time. This is another aphorism that didn’t originate with Chichester but one to which he strictly adhered. He maintained a strong sense of the known present—whatever task or trouble that occupied him at the time—without allowing himself to become paralyzed by fear of the unknown future. He concerned himself with each day’s time, speed, and distance run and refused to become distracted with worry about where he would be in a week or a month. He addressed his attention to the weather on the near horizon, not the unseen beyond. He reveled in the warm sunshine and hunkered down in the gales as they came, not bothering to wonder when they would come again.

“To sleep, perchance to dream . . . ” Sleep is essential not just to good judgment and good health, but to our very survival. Chichester understood this and, he tells us, became a champion sleeper during his circumnavigation. While the lethargy and apathy he experienced at times was likely due in part to depression, he wrote often of the clarifying effect of a good night’s sleep on his ability to face difficult tasks and trying situations.

In the end, of course, none of us is Chichester or Neil Armstrong or Robert Peary or any of the larger-than-life heroes of history’s epic adventures. Each of us has to find his own way toward the lesser peaks of his own experience. I for one am better prepared for having read Chichester’s tale to make my passage toward whatever fate awaits me, beyond the wide horizon.

January 25, 2015

Atlantic Circle: a review

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle Kathryn Lasky is well known as a prolific author of award-winning and popular children’s books. Her Guardians of Ga’Hoole series became a major motion picture (Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole) released by Warner Brothers in 2010. She is not as well-known—but by golly she ought to be—for her sailing memoir, Atlantic Circle, published by Norton in 1985 under her married name, Lasky Knight, and recently released on Kindle.

Kathryn Lasky is well known as a prolific author of award-winning and popular children’s books. Her Guardians of Ga’Hoole series became a major motion picture (Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole) released by Warner Brothers in 2010. She is not as well-known—but by golly she ought to be—for her sailing memoir, Atlantic Circle, published by Norton in 1985 under her married name, Lasky Knight, and recently released on Kindle.

I bought the hardcover copy of Atlantic Circle the year it came out, when I was a newly minted lawyer looking for ways to dissolve the extra money I was bringing home from my first real job. I found the most efficient money-solvent on Earth in a sailboat shop not far from my first apartment. I shudder to think of all the dollars washed down the wakes of various sailboats I have owned since then (four sloops, one cutter, two catboats, and one ketch), thanks in part to Ms. Lasky’s little book.

Atlantic Circle is a wonderfully conversational and sometimes laugh-out-loud funny look at the macho business of crossing an ocean in a small boat, told by the self-confessed “Jewish American Princess” shanghaied aboard a thirty-foot ketch given to her and her husband Chris as a wedding present. Lasky objects at first to the princess label but concedes that if it means having “money and privilege,” she and her sister fit the term growing up. “We were indulged but not spoiled,” she says. “There is a difference, I think.” In reading Lasky’s story, the difference couldn’t be more apparent. Clearly, Christopher Knight found himself a longsuffering pearl of a girl. In fact, after reading about her seventy-year-old mother Hortense, green with seasickness but soldiering on after joining her daughter for a rough European leg of the voyage, one can scarcely doubt that this strength of character runs in the family.

Those looking for another overblown installment in the sailing-adventure genre will not find one here, thank God. Lasky spends just enough time describing precipitous breaking waves, purple squalls, and howling gales to give the reader a feel for the experience and no more. Instead, we are invited on long meanders through the author’s past before joining her inward journey as the often terrified, sometimes despondent, but always faithful crew. Speaking to us from a windswept deck in the North Sea or from the bunk where the author often hunkered, below, her writing sparkles throughout. The reader gets the sense of sitting down for a chat about life, good food, and the pursuit of happiness with a thoughtful, wise and witty friend.

The author, then.

The story begins with what Lasky describes as “the bargain in the sky.” While riding along and imagining a fiery death in the small plane flown by Chris as he barnstorms the rocky coast of Maine, Lasky agrees to cross the Atlantic in a sailboat if Chris will give up flying. A bargain is struck, and the die is cast.

Before we weigh anchor with the newlyweds, we get a closer look at the families on both sides of the aisle and the “fundamental differences” between the two. While Chris and his New England kin are the saltiest of salty dogs, Kathy describes herself as “strictly an ‘amber waves of grain’ sort.” Her father dabbled in racing Thistles on a lake in the Midwest, but only briefly. When her mother fell during a sail change and her father started yelling encouragement, Kathy remembers her mother, “still bleeding,” saying in a “dangerously sweet voice,” “Marven, you know what you can do with your goddamn spinnaker?”

The first leg of the voyage follows the shorter but more arduous northern Atlantic route to Europe from New England—the same one the Titanic failed to complete coming the other way. This route is recommended for August departures from the U.S. to ensure good weather and westerly winds in the higher latitudes, but Lasky and her husband leave in June when, predictably, they encounter fog, cold, and two prolonged spells of winds above forty knots right on the nose. But with youth, luck, pluck, and love on their side, somehow they make it all work.

An endearing quirkiness comes across in photos of Lasky as a gangly young bride, girded for battle in a wool watch cap and weathers against a background of foggy, bleak seas, fearing death no less than she did in the air but sticking to the “bargain” and managing a pitiable, half-hearted smile for the camera. These images are all the more poignant after you have read about her as the girl who took water ballet in college and “eventually became the lead dolphin in a group called The Wet Dreams.” There is nothing about this woman that was made for a rugged life on the ocean, as she forlornly admits. And yet she goes. Along the way, despite an often vulnerable goofiness (she packs—and eats—dozens of bags of Pepperidge Farm cookies; she falls overboard in the canals of Europe; she hoists a storm jib upside down in a gale; she tosses her cookies and her favorite meal of the trip into the Med), Lasky’s grit and keen intellect always shine through.

The author, now.

Atlantic Circle was published before the Internet age, and the few reviews recently posted on Amazon don’t reflect this book’s enthusiastic audience at the time of its release. Judging from the snarkier comments, some readers have missed the point in complaining that the story does not move quickly in a straight line to the next wave, the next storm, the next port, and so forth. This is not fast food for the drive-through reader but a luxurious feast for the literary gourmand. It’s less about what happens next and more about why, exactly, two perfectly sane, healthy young people with careers, loving families, and lots to do right at home would say goodbye to all that for the desolation of the open ocean. The question begs for an answer, and while Lasky is never confident she knows what it is, she treats us to an intimate and often humorous look at her struggle to find one while keeping her sanity, her marriage, and her vessel intact. Somehow she manages to succeed in the end, discovering peace and balance at the water’s edge. We are richly rewarded by her journey.

January 22, 2015

Back to Happy: a review

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle And now for something totally different . . .

And now for something totally different . . .

has written a wonderful new book. Flowing from the unfathomable grief of the loss of her first child, Meghan, to a congenital heart and lung condition at age six, it is a story filled with insight, advice and inspiration for women and mothers, especially, on how to navigate the tragedies that affect us all and find the way “Back to Happy.” The book as you might guess came to me in an unusual way.

Connie, her future husband Rob, and I attended a sleepy, small liberal arts college in the hills of Western Maryland in the seventies. Although I cannot recall a single intelligible word I ever said to her, I remember her well as the impossibly beautiful brunette whose photograph could have appeared in the dictionary beside the definition of the term, “out of my league.” For thirty years, I had no idea nor any reason to wonder what happened to Connie, but through the weird miracle of Facebook, I have come to admire her career and that of her famous second child, Caroline Bowman, a Broadway star known for her performances in Kinky Boots and as Eva Perone in Evita. Just last fall, Caroline, who is the image of her mother as a young girl, was cast as one of the two sisters leading the Broadway production of Wicked.

Back to Happy, A Journey of Hope, Healing, and Waking Up, sounds a number of themes familiar to women’s self-help literature but does so with an endearing freshness and authenticity born of Connie’s and Rob’s remarkable, personal story. At just 72 pages, it is a quick read in which the author imparts, in nine “lessons” divided into chapters, what she learned going through her own “dark night of the soul.” Meghan’s story is woven through these lessons as the author reveals the sources of a mother’s strength in coping with her daughter’s illness and death, including prayer, twelve-step recovery philosophy, yoga, Reiki, meditation, the experiences of friends, and a Christian view of the world as one in which God is in control. With these tools, she encourages those in suffering to practice acceptance as a path to peace.

The text is annotated with links to the author’s online podcasts and other helpful references. Although I was not able to access these on my Kindle Paperwhite, they are available on the author’s website. There, next to the author’s name, you will find her personal motto, “peaceful exuberance,” which well summarizes her central message. Back to Happy is a thoughtful and well-written book that will bring comfort and understanding to those in suffering. The author makes good on her promise to offer the reader tried and true methods to travel through life’s ups and downs “with more grace and ease.” It’s clear by the end of the book that Connie has done exactly that.

Available on Amazon in Kindle format, paperback, and audiobook.