Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 494

June 16, 2012

Markets in everything

Conflict Kitchen is a take-out restaurant that only serves cuisine from countries with which the United States is in conflict. The food is served out of a take-out-style storefront that rotates identities every six months to highlight another country. Each iteration of the project is augmented by events, performances, and discussions that seek to expand the engagement the public has with the culture, politics, and issues at stake within the focus country. These events have included live international Skype dinner parties between citizens of Pittsburgh and young professionals in Tehran, Iran; documentary filmmakers in Kabul, Afghanistan; and community radio activists in Caracas, Venezuela.

That is in Pittsburgh, and Cuba and North Korea are on the way. Here is more, and for the pointer I thank Michael Rosenwald.

Is a high home ownership rate a sign of a successful country?

I saw an El Pais spread on this, which I cannot find on-line. Here are the European countries with the highest owner occupancy rates:

1. Romania, 97.5%

2. Lithuania, 93.1%

3. Croatia, 90.1%

4. Slovakia, 90.0%

How about the lowest rates?

1. Switzerland, 44.3%

2. Germany, 53.2%

3. Austria, 57.4%

Get the picture?

June 15, 2012

European City-States and Economic Growth

A long tradition claims that one factor that distinguished western Europe from China, the Middle East, and Russia was the presence of independent city-states. Max Weber, Henri Pirenne, and John Hicks argued that city-states played a crucial role in beginning the long road to modern economic growth (see this earlier MR post on producer and consumer cities).

De Long and Shleifer (1993) argued that city-states ruled by merchants favored policies that protected property rights and markets and that they imposed lower taxes than princely states did. But historians have found that cities like Florence actually imposed much higher taxes than feudal states did (see Epstein 1991, Epstein 1993 [JSTOR links], or Epstein 2000). Until now, however, no-one (to the best of my knowledge) has provided systematic evidence on the economic performance of independent city-states across Europe. A new paper by David Stasavage attempts to do just this. Using city population as a proxy for economic development, he finds that autonomous city-states overall didn’t grow faster than other cities. Interestingly, new city-states which had been independent for less than 200 years did grow faster. After more than 200 years of independence, growth in these independent cities slowed and they grew more slowly than did ordinary cities.

Stasavage interprets this finding in terms of a model of oligarchies proposed by Acemoglu (2008). Oligarchies initially have an incentive to impose institutions that favor markets and economic growth. However, oligarchies also impose barriers to entry, and over time these barriers to entry lead to growth slowing down. Other (complementary) mechanisms may also have been at work. In particular, Stasavage does not consider the role of external warfare. Once they became rich and prosperous, city-states were often attacked by neighboring territorial states. Many city-states then had to impose high taxes and other extractive policies in order to survive. In any case, these findings are significant for an argument that I will evaluate in subsequent posts that claims that the rise of state capacity played an important role in getting growth going in early modern Europe.

“Scene of the Verge of the Hay-Mead”

That is a chapter from Far From the Madding Crowd, which remains a much underrated Thomas Hardy novel. This chapter is a masterpiece of behavioral economics, most of all on matters of courtship and romance. It is difficult to excerpt, because it relies so much on the sequence of events and dialog. You can read it free here. There are other sources, including MP3s, here.

The Greek countercyclical asset

A clerk said books on economics and do-it-yourself guides were selling briskly, as were escapist thrillers and philosophy, especially works by Arthur Schopenhauer, known for his pessimism and his conviction that human experience is not rational or understandable.

There is more here, and I thank Asher Meir for the pointer.

Guest Blogger: Mark Koyama

We are pleased to have Mark Koyama blogging with us through Monday. Mark, our colleague at GMU, is an economic historian with an interest in institutional economics and the relationship between culture and economic performance. Mark’s paper on witches, taxes and the rule of law (with Noel Johnson) was recently covered at the Washington Post. Mark has also just published a paper in the Journal of Legal Studies on prosecution associations. Prosecution associations were private providers of insurance and police services in in early nineteenth-century England in the years before public police.

Mark’s career, however, has had one unusual feature. Mark began blogging as a student at Oxford but when he became a professor at GMU he defied all tradition and stopped blogging! We are thus happy to bring Mark back to the fold.

Has Africa always been the world’s poorest continent?

Jeff Sachs claims that Africa was always the poorest continent in the world, that many parts of Africa have never experienced economic growth, and that comparisons between African countries and Asian countries are highly misleading (see in this video for example).

Until recently it has been hard to establish basic stylized facts about African development because GDP data only goes back to 1960, but Ewout Frankema and Marlous van Waijenburg have been able to compile internationally comparable real wages estimates back to the 1880s (pdf). They follow Bob Allen’s influential methodology, constructing representative consumption bundles, and then seeing how many bundles an unskilled worker could obtain. The welfare ratios that result show that it simply makes no sense to talk about African economic performance in general in the colonial period.

There were at least two distinct economies in British colonial Africa, a comparatively high-wage, labor scarce, economy in west Africa, and a low-wage economy in east Africa. Real wages in many west African cities grew more or less continuously, from the 1880s until the 1930s, as these economies enjoyed a boom in commodity exports, and west African wages exceeded wages in many Asian cities through the colonial period. The story of poverty and stagnation in modern west Africa is not a story of permanent stagnation, but of growth collapses and growth reversals (especially in the 1970s and 1980s).

In contrast, real wages were extremely low in British east Africa. Many east African economies like Kenya never experienced rapid growth in the colonial period. It was the crisis of the 1970s that created the current view we have of all of sub-Saharan Africa as sharing a common set of problems. Modern Ghana, or the Gold Coast was roughly twice as rich as Kenya in the colonial period, but by the 1980s per capita GDP in the two countries was the same. Were the high real wages of the colonial period solely the rest of labor scarcity? (like the high wages recorded in medieval Europe after the Black Death) or did they represent a genuine moment of opportunity that could have led to sustained economic growth?

Consider this evidence in light of recent optimism about growth rates in Africa in the 2000s (see this MR post). Like the increase in real wages that occurred in the colonial period, recent growth has been driven by an export boom and rising commodity prices. These findings suggest that episodes of economic growth are less rare in African history that we might previously have supposed. Instead, perhaps the real difficulty lies in sustaining economic growth, and not in getting growth going for a few years.

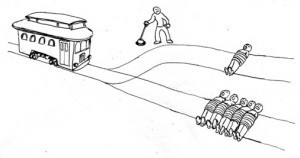

The Google-Trolley Problem

As you probably recall, the trolley problem concerns a moral dilemma. You observe an out-of-control trolley hurtling towards five people who w ill surely die if hit by the trolley. You can throw a switch and divert the trolley down a side track saving the five but with certainty killing an innocent bystander. There is no opportunity to warn or otherwise avoid the disaster. Do you throw the switch?

ill surely die if hit by the trolley. You can throw a switch and divert the trolley down a side track saving the five but with certainty killing an innocent bystander. There is no opportunity to warn or otherwise avoid the disaster. Do you throw the switch?

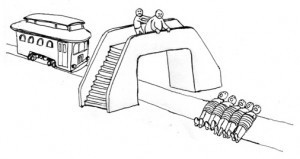

A second version is where you stand on a bridge with a fat man. The only way to stop the trolling killing five is to push the fat man in front of the trolley. Do you do so? Some people say no to both and many say yes to switching but no to pushing, referring to errors of omission and commission. You can read about the moral psychology here.

A second version is where you stand on a bridge with a fat man. The only way to stop the trolling killing five is to push the fat man in front of the trolley. Do you do so? Some people say no to both and many say yes to switching but no to pushing, referring to errors of omission and commission. You can read about the moral psychology here.

I want to ask a different question. Suppose that you are a programmer at Google and you are tasked with writing code for the Google-trolley. What code do you write? Should the trolley divert itself to the side track? Should the trolley run itself into a fat man to save five? If the Google-trolley does run itself into the fat man to save five should Sergey Brin be charged? Do your intuitions about the trolley problem change when we switch from the near view to the far (programming) view?

I think these questions are very important: Notice that the trolley problem is a thought experiment but the Google-trolley problem is a decision that now must be made.

A bit of longer term perspective on state and local governments

That is from Matt Mitchell, the source is here. Josh Barro has a very good post on the rising costs of employing public sector workers.

June 14, 2012

More food writers should be making this kind of point

Arabic Knowledge@Wharton: So when companies like Wal-Mart bring their logistics ability to Africa, it actually could be a good thing for the poor people of Africa?

Cowen: It’s exactly what we need more of. Yes.

Arabic Knowledge@Wharton: Yet there’s a fear Wal-Mart will put the smaller stores out of business.

Cowen: Yes, they do so sometimes, but they do so by charging lower prices. It makes it more accessible and more reliable. It’s not just the pricing at any one point and time. It’s what happens in the very worst periods. Companies like Wal-Mart are very, very good at keeping up supply and being regular.

Here is more, in interview form. Much of the discussion is about the Middle East:

Plus, it depends on which country in the Middle East you’re talking about. So Tunisia is better run than most places. Lebanon has a saner agricultural policy than most places. Yemen is a total disaster. Algeria and Egypt have not gone so well. So there’s a lot of variety within the Middle East. If you think of a model like Turkey, which isn’t technically in the Middle East, they’ve liberalized and encouraged agribusiness. Turks are much better fed than 20 years ago. When you ask a country like Iran, what should we do? It’s hard to know even where to start.

And this:

I’m not even sure Yemen is even a viable country because there’s some chance, they will literally run out of water in the next 20 years in a lot of parts of the country. At this point, I don’t know what they can do.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers