Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 493

June 18, 2012

When are ‘secure’ property rights bad for growth?

Greg Clark has argued that private property was secure in medieval England on the basis that

‘Medieval farmland was an asset with little price risk. This implies few periods of disruption and uncertainty within the economy, for such disruption typically leaves its mark on the prices of such assets as land and housing’ (p 158).

And on the basis of low taxes in medieval England, he goes on to claim that:

’if we were to score medieval England using the criteria typically applied by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to evaluate the strength of economic incentives, it would rank much higher than all modern high-income economies—including modern England’ (p 147) . . . If incentives are the key to growth, then some preindustrial societies like England had better incentives than modern high-income economies. And incentives may be much less important to explaining the level of output in economies than the Smithian vision assumes’ (p 151).[image error]

Even if most would not go so far as Clark, many economic historians now argue that property rights were secure in late medieval and early modern England, and that some property rights actually became less secure after the Glorious Revolution. Drawing on the work of Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Dan Bogart, and Gary Richardson, Bob Allen summarizes these findings as follows:

‘Growth was also promoted by Parliament’s power to take people’s property against their wishes. This was not possible in France. Indeed, one could argue that France suffered because property was too secure: profitable irrigation projects were not undertaken in Provence because France had no counterpart to the private acts of Parliament that overrode property owners opposed to the enclosure of their land or the construction of canals or turnpikes across it’

See here, here and here for links to the academic work that underpins these claims. For the sake of argument let us agree that they are correct. What does this finding mean?

It does not mean that insecure property rights are good for growth.

It does mean that feudalism was bad for growth.

The property rights that Clark and others describe as being secure in medieval Europe were feudal property rights. Feudalism structured ownership rights in such a way as to channel rents to the king and the military elite. Feudal property rights were designed to maintain concentrated holdings of land, large enough to support feudal armies. Feudal laws limited land sales that would break-up large estates and bundled together rights over land with rights over individuals.

In a market economy, where rights are clearly defined, assets will be allocated to their highest-value user so long as transaction costs are not too high. In this type of environment protecting asset holders from expropriation provides the best incentives for investment and growth. But this was not true of the medieval world.

What Bogart and Richardson establish is that these feudal rights impeded efficient land use in England and made it difficult to organize the provision of public goods. They show how Parliament in the 18th century was able to rewrite and override existing property rights. Their work suggests that given the initial allocation of rights and the extremely high transactions costs associated with feudal land law, a reconfiguration of property rights was necessary for economic growth to begin.

*The Locavore’s Dilemma*

The authors are Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu, and the subtitle is In Praise of the 10,000 Mile Diet:

The publisher’s page summarizes it thus:

Today’s food activists think that “sustainable farming” and “eating local” are the way to solve a host of perceived problems with our modern food supply system. But after a thorough review of the evidence, Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu have concluded that these claims are mistaken.

In The Locavore’s Dilemma they explain the history, science, and economics of food supply to reveal what locavores miss or misunderstand: the real environmental impacts of agricultural production; the drudgery of subsistence farming; and the essential role large-scale, industrial producers play in making food more available, varied, affordable, and nutritionally rich than ever before in history.

They show how eliminating agriculture subsidies and opening up international trade, not reducing food miles, is the real route to sustainability; and why eating globally, not only locally, is the way to save the planet.

I very much enjoyed reading the book, you can order a copy here. For the pointer I thank Daniel Klein.

Assorted links

2. Euro 2012 markets in everything.

3. Scott Sumner’s favorite things Icelandic.

4. Robin Hanson: writing a book, and turning his blog into a group blog.

5. Did the robot pass or the humans fail this “composing Turing test”?

6. Guitars now being made by 3-D printers.

Assorted Links

1. Valve, the game company, hires Yanis Varoufakis, expert on the European situation, to help deal with balance of payment and currency issues between different worlds.

2. The great Deirdre McCloskey lets loose on the high liberals of political philosophy. Read the whole thing, it builds to gale force.

3. Aussie retailers charging more if you use an “old” browser.

4. The U.N. Internet Power Grab revealed by WCITLeaks a project of GMU economists Eli Dourado and Jerry Brito.

Institutions and Islamic Law

Adeel Malik has a very interesting essay responding to Timur Kuran’s excellent book The Long Divergence. There are many previous MR posts on Kuran’s thesis that Islamic law impeded the transition to impersonal exchange in the Middle East (see here and here).

I think The Long Divergence is one of the most important recent contributions to New Institutional Economics (incidentally I reviewed it for Public Choice). Malik takes on board Kuran’s main argument but then argues that it is not institutional enough because it does not tackle the argument that Islamic law was endogenous to the politics of the region.

‘Islamic law can be described, at best, as a proximate rather than a deep determinant of development, and that there is limited evidence to establish it as a causal claim. Finally, I propose that, rather than exclusively concentrating on legal impediments to development, a more promising avenue for research is to focus on the co-evolution of economic and political exchange, and to probe why the relationship between rulers and merchants differed so markedly between the Ottoman Empire and Europe.’

June 17, 2012

Lack of trust is one reason why macro policy is underperforming

From my latest NYT column, here is one excerpt:

During the financial crisis, the prices of stocks, homes and other assets all fell, leaving the American public feeling less wealthy. In fact, the Federal Reserve reported last week that the crisis had erased almost two decades of accumulated prosperity for a typical family. The American economy and its financial system failed a giant stress test, at least when compared with previous expectations. Feeding the fears today are the crisis in the euro zone, the slowdown in China and political polarization at home.

In short, there is a prevailing sense that we are simply not as safe, financially speaking, as we used to be. The productive capacity of the economy may appear largely intact, but the perceived risk is significantly higher.

Think of hiring as a business investment, and that investment often requires:

1. A not too high risk premium

2. Consensus within organizations, and thus trust within organizations

3. Commitments from banks that they will provide liquidity when needed and not flinch in light of pressures to cut their balance sheets

4. Ability to afford concomitant capital costs

5. Ability to scale up rapidly if the new projects “hit paydirt”

6. Consumers perceive they have enough wealth to (potentially) become captive customers of a new and successful product

7. Affordable real wages

Inflating away the real wage helps with #7 — and that can be a big help indeed — but it is far from the entire picture. When trust is low, both monetary and fiscal policy will underperform, relative to textbook predictions.

Here is another bit:

In response, some people have moralized about this shift — sometimes by telling voters they’re stupid to let government shrink. But that kind of talk can lower public trust even further.

If your blogging or writing doesn’t increase the degree of trust among people who do not agree with each other, probably you are lowering the chance for better policy, not increasing it, no matter what you perceive yourself as saying. I also wrote:

Although Sweden and Switzerland have had effective monetary policies recently, both of those countries have especially high rates of trust in government.

And high trust in each other. I could have added Iceland to that list.

Taxes and the Onset of Economic Growth

In a recent book Besley and Persson 2011 argue that fiscal capacity is strongly correlated with economic performance across countries (see also here and here). They cite important historical work by Mark Dincecco who has shown that across Europe, between 1650 and 1900, higher taxes were associated with both limited government and economic growth (see here). The following graph is from Dincecco (2011) which contains similar figures for other European countries.

This finding can be interpreted in many ways. The state capacity literature emphasizes the idea that governments need an adequate tax system in order to provide the institutional preconditions necessary for economic growth.

Perhaps there is an alternative explanation for the historical correlation between higher taxes and economic growth. This has to do with selection bias in historical data sets. Modern states did not emerge out of nowhere. They replaced pre-existing local systems of taxation, patronage, and rent seeking. We have a relatively large amount of information about what strong, central, governments were doing and what taxes they were collecting. However, we do not have much information about local regulations or tax systems that existed before the rise of modern states because these local institutions were subsumed or destroyed by the state-building process. There is plenty of evidence that these local systems imposed large deadweight losses, although it is difficult to put together a database measuring how large these distortions were (see this paper by Raphael Frank, Noel Johnson, and John Nye or just read about the Gabelle; also see Nye (1997) for this point).

The implication of this argument is that an increase in the measured size of central government need not have been associated with an increase in the total burden of government. Rather the total deadweight loss of all regulations and taxes could have gone down in the 18th and 19th centuries, even as the tax rates imposed by the central state went up.

(Note: the increase in per capita revenues in England depicted in the figure is largely driven by higher rates of taxation (notably the excise) and more effective tax collection and not by Laffer curve effects (although the growth of a market economy during the 18th century did make it easier for the state to collect taxes).

Structural theories of unemployment, vindicated as part of the puzzle

From the new AER, by Michael Elsby and Matthew Shapiro:

That the employment rate appears to respond to changes in trend growth is an enduring macroeconomic puzzle. This paper shows that, in the presence of a return to experience, a slowdown in productivity growth raises reservation wages, thereby lowering aggregate employment. The paper develops new evidence that shows this mechanism is important for explaining the growth-employment puzzle. The combined effects of changes in aggregate wage growth and returns to experience account for all the increase from 1968 to 2006 in nonemployment among lowskilled men and for approximately half the increase in nonemployment among all men.

You will find many weak structural theories criticized (at length) in the blogosphere, but the stronger versions hold up. This is very likely one reason why the labor market and output response in recent years has been so weak. It doesn’t require any stories about companies searching desperately for quality computer programmers, and so showing the generality of unemployment across professions or regions isn’t much of a response to the stronger structural theories.

The Iron Law of Shoes

That is what Dan Klein and I used to call it. Now there is some research, by Omri Gillath, Angela J. Bahns, Fiona Ge, and Christian S. Crandall:

Surprisingly minimal appearance cues lead perceivers to accurately judge others’ personality, status, or politics. We investigated people’s precision in judging characteristics of an unknown person, based solely on the shoes he or she wears most often. Participants provided photographs of their shoes, and during a separate session completed self-report measures. Coders rated the shoes on various dimensions, and these ratings were found to correlate with the owners’ personal characteristics. A new group of participants accurately judged the age, gender, income, and attachment anxiety of shoe owners based solely on the pictures. Shoes can indeed be used to evaluate others, at least in some domains.

The piece is called “Shoes as a Source of First Impressions,” and for the pointer I thank @StreeterRyan. Via Mark Steckbeck, an ungated copy is here, for the price of your email address.

June 16, 2012

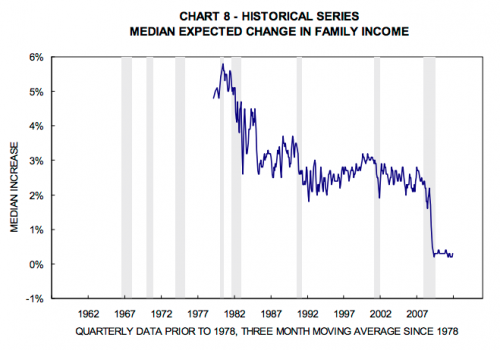

Median expected change in family income

Putting TGS issues aside, this is one reason why many of us do not see today’s macroeconomic problems as exclusively cyclical:

For the pointer I thank @rortybomb.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers