Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 321

August 7, 2013

Is Amazon Art a doomed venture? Let’s hope so

I do not think it will revolutionize the art world:

Amazon has just announced that it’s partnered up with over 150 galleries and art dealers across the US to sell you fine art through its new initiative Amazon Art.

The site offers over 40,000 original works of fine art, showcasing 4,500 artists. That, perhaps unsurprisingly, makes it the largest online collection of art directly available from galleries and dealers. Partners in the project include Paddle8 in New York, the McLoughlin Gallery in San Francisco, and the Catherine Person Gallery in Seattle.

Last month, the Wall Street Journal reported that Amazon—which will reportedly take a 5 to 20 percent cut on all sales—was planning to launch the new service. At the time, it seemed that plenty of galleries thought that selling art online via Amazon may be distasteful. Clearly, that negative feeling hasn’t stopped Bezos & Co..

Given Amazon’s last attempt at selling art—a project with Sotheby’s back in 2000 — only lasted 16 months, it’ll be interesting to see how the initiative works out.

I expect the real business here to come in posters, lower quality lithographs, and screen prints, not fine art per se. And sold on a commodity basis. There is nothing wrong with that, but I don’t think it will amount to much more aesthetic importance than say Amazon selling tennis balls or lawnmowers.

Should you buy this mediocre Mary Cassatt lithograph for “Price: $185,000.00 + $4.49 shipping”? (Jeff, is WaPo charging you $250 million plus $4.49 shipping? I don’t think so. )

One enduring feature of the art world is that a given piece will sell for much more in one context rather than another. The same painting that might sell for 5k from a lower tier dealer won’t command more than 2k on eBay, if that. Yet it could sell for 10k, as a bargain item, relatively speaking, if it ended up in the right NYC gallery (which it probably wouldn’t). Where does Amazon stand in this hierarchy? It doesn’t look promising.

Their Warhols are weak and overpriced, even if you like Warhol. Are they so sure that this rather grisly Monet is actually the real thing? I say the reviews of that item get it right. At least the shipping is free and you can leave feedback.

I’ve browsed the “above 10k” category and virtually all of it seems a) aesthetically absymal and b) drastically overpriced. It looks like dealers trying to unload unwanted, hard to sell inventory at sucker prices. I’m guessing that many of these are being sold at multiples of three or four over auction price histories. Is this unexceptional John Frost worth even a third of the 150k asking price? Maybe not.

Amazon wouldn’t sell you a kitchen blender that doesn’t work, or that was triple the appropriate cost, so why should they sully their good name by hawking art purchase mistakes? If you’ve built the best web site in the history of the world, which they have, you may decide that quality control should not be tossed out the window. Much as I admire their shipping practices, what makes Amazon work for me is simply that they sell better stuff and a wider variety at cheaper prices. Why give that formula up by treading into a market where such an approach won’t make any money? Why compete in a market where an awesomely speedy physical delivery network means next to nothing?

Overall, I don’t see the advantage of Amazon over eBay in this market segment. One nice thing about eBay is that you can see if anyone else is bidding and also that surprise quality items pop up on a relatively frequent basis, due to a fully decentralized supply network. You also can hope for extreme bargains and indeed I have snagged a few in my time. On the new Amazon project, supply is restricted to a relatively small number of bogus, mainstream galleries, about 150 of them according to the publicity.

eBay has the advantage with “free for all,” and good galleries and auction houses have the advantage when it comes to certification and pricing reliability. I don’t see the intermediate niche that Amazon is supposed to be trying to fill.

I’m a big fan of Jeff Bezos buying The Washington Post, but if you’re looking for the case against that move, just click on that Monet purchase and see what happens.

August 6, 2013

Wu Jinglian

The first sentence of this MIT Press book — entitled Wu Jinglian — reads “Wu Jinglian is widely acknowledged to be China’s most influential and celebrated economist.”

Almost every page of this book is insightful on Chinese economics or politics or usually both together. And it will remind you that China is still ruled by the Communist Party. Wu Jinglian is a fan of James M. Buchanan and Douglass C. North, by the way. Here is Wu Jinglian on Wikipedia.

Recommended.

Assorted links

2. How good would LeBron James be at football? And a fun discussion of Jeff Bezos. Here is why WaPo is not a vanity project for Bezos. And Raghu Rajan has just been appointed RBI Governor.

3. The food culture that is Indiana.

4. Timur Kuran on political Islam, Turkey, and Egypt.

5. The Henry Hazlitt archives.

6. Dutch baboons go on strike.

Liberalization Increases Growth

In Assessing Economic Liberalization Episodes: A Synthetic Control Approach (wp version), Billmeier and Nannicni evaluate economic liberalizations, defined as “comprehensive reforms that extend the scope of the market, and in particular of international markets,” over the period 1963-2005. The authors compare real per-capita GDP in treatment countries with that in a synthetic control, a weighted average of similar countries with the weights optimized so that the synthetic control matches as well as possible a variety of pre-treatment characteristics including secondary school enrollment, population growth, and the investment share as well as GDP. The results are often impressive, for example.

[In Indonesia] the average income over the years before liberalization is literally identical to that of the synthetic control, which consists of Bangladesh (41%), India

(23%), Nepal (23%), and Papua New Guinea (13%). After the economic liberalization in 1970, however, Indonesian GDP per capita takes off and is 40% higher than the estimated counterfactual after only five years and 76% higher after ten years.

Here is a selection of figures (see the paper for more). In each case the solid line is the liberalizing country and the dashed line the synthetic control.

To be sure, not all liberalizations are successful. In particular, liberalizations in Africa especially after 1991 appear to be less successful. Whether this is because these liberalizations were half-hearted, were not combined with other institutional improvements or because countries that liberalized earlier were better able to link to global supply chains, is unclear. See the paper for more discussion.

These results bolster similar earlier findings from Warciarg and Welch (2008) who, using different methods, examined the average effect of liberalizations on growth from a wide variety of countries over a 50 year period. They found that on average growth increased after liberalization by a remarkable 1.5 percentage points. Here is the key figure.

See Development and Trade: The Empirical Evidence, a video from MRU, for more on the WW study as well as other types of evidence.

Has the U.S. labor market adjusted?

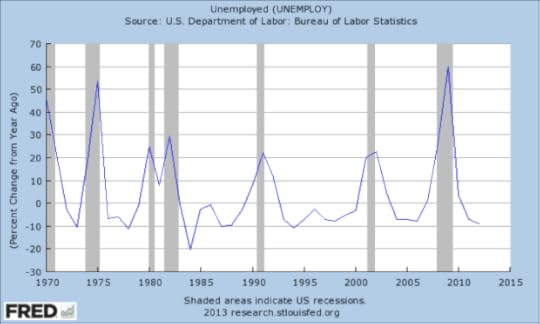

Via Ashok Rao, this is a scary chart:

If read “crudely,” the chart suggests that in terms of percentage changes, we already have seen a historically normal level of adjustment. There is an interesting discussion at the link.

By the way, if you’re not already, you all should be reading Ashok Rao.

August 5, 2013

Do consensual labor markets have a future in Germany?

The practice seems to be on a decline, according to this recent piece in The Economist:. For instance:

…the unions are continuing to lose members, as the older industries where they are entrenched trim jobs. Newer companies, especially in areas such as e-commerce, security firms and fitness studios, are “almost entirely without collective representation”, says Martin Behrens at the Hans Böckler Stiftung, a union-linked think-tank.

Workers at any German company with five or more employees can demand the creation of a works council. But in 2011 only 12.5% of all companies had one, down from 13.4% the year before. Only 659 German firms had supervisory boards with worker representatives in 2011, compared with 708 in 2007. Ironically, as America’s carmaking union seeks to bring Germany’s labour-market model into Volkswagen’s factory in Tennessee (see article), its future seems increasingly in doubt back home.

Here is a recent NYT piece on how Amazon’s labor practices clash with German union traditions.

Google, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook will own lots of content

These days the natural monopoly of Apple is looking less permanent, but here is what I wrote a short while ago:

I expect two or three major publishers, with stacked names (“Penguin Random House”), and they will be owned by Google, Apple, Amazon, and possibly Facebook, or their successors, which perhaps would make it “Apple Penguin Random House.” Those companies have lots of cash, amazing marketing penetration, potential synergies with marketing content they own, and very strong desires to remain focal in the eyes of their customer base. They could buy up a major publisher without running solvency risk. For instance Amazon revenues are about twelve times those of a merged Penguin Random House and arguably that gap will grow.

There is no hurry, as the tech companies are waiting to buy the content companies, including the booksellers, on the cheap. Furthermore, the acquirers don’t see it as their mission to make the previous business models of those content companies work. They will wait.

Did I mention that the tech companies will own some on-line education too? EduTexts embedded in iPads will be a bigger deal than it is today, and other forms of on-line or App-based content will be given away for free, or cheaply, to sell texts and learning materials through electronic delivery.

Much of the book market will be a loss leader to support the focality of massively profitable web portals and EduTexts and related offerings.

With the sale of The Washington Post to Jeff Bezos (btw not to the company), we have now taken one step down this road.

Assorted links

1. Memoir of Bombay.

2. Your Japanese toilet can be hacked.

3. Photos from a visit to the Yakuza.

4. Public unions and ACA nervousness.

5. I am pleased to have made this Time list of the best bloggers. The discussion of MR is here.

6. Free download of Calestous Juma, The New Harvest, a very good book on agriculture in Africa.

7. How do dogs show their love? And do they actually have mixed emotions toward you?

Is the main effect of the minimum wage on job growth?

In their new paper, Jonathan Meer and Jeremy West report:

The voluminous literature on minimum wages offers little consensus on the extent to which a wage floor impacts employment. For both theoretical and econometric reasons, we argue that the effect of the minimum wage should be more apparent in new employment growth than in employment levels. In addition, we conduct a simulation showing that the common practice of including state-specific time trends will attenuate the measured effects of the minimum wage on employment if the true effect is in fact on the rate of job growth. Using a long state-year panel on the population of private-sector employers in the United States, we find that the minimum wage reduces net job growth, primarily through its effect on job creation by expanding establishments.

In a slightly different terminology, the effect of the minimum wage may well be attenuated in the short run, but over longer time horizons there is a “great reset” against low-skilled labor.

The importance of mobile Mexican labor

A novel empirical test reveals that natives living in cities with a substantial Mexican-born population are insulated from the effects of local labor demand shocks compared to those in cities with few Mexicans. The reallocation of the Mexican-born workforce among these cities reduced the incidence of local demand shocks on low-skilled natives’ employment outcomes by more than 40 percent.

That is from Brian C. Cadena and Brian K. Kovak. Here is a related post from Modeled Behavior. You can think of the mobile Mexican labor as providing risk insurance for low-skilled labor markets. It is a further interesting question what this result implies for the aggregate impact of immigration on low-skilled wages, but I don’t see that there is a ready answer a priori, at least not based on the results of this paper. The local geographic swings could be significant, while the aggregate impact could be either high or low.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 843 followers