Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 318

August 12, 2013

*Mass Flourishing*

The author is Edmund Phelps and the subtitle is How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and Change.

The book’s home page is here.

Assorted links

1. Are hedge funds actually about, believe it or not…hedging?

3. Interesting Noah Milliman piece on Bezos and WaPo.

4. Critical review of Reza Aslan.

5. It is cheaper to fly in the German orchestra than to pay the Australian musicians.

6. Details for my August 23rd lecture in Singapore, do come and introduce yourself. Note that while the talk is free, you must register in advance and there is a penalty charge for no-shows. The time for the talk is missing on the announcement and that is 3-5.

The Great Reset, labor market edition

The lowest-wage sectors have consistently produced 40 percent to 50 percent of the job gains in recent recoveries.

Here is more, and there are further pictures here.

Fabio Rojas on Twitter as an electoral predictor

It turns out that what people say on Twitter or Facebook is a very good indicator of how they will vote.

How good? In a paper to be presented Monday, co-authors Joseph DiGrazia, Karissa McKelvey, Johan Bollen and I show that Twitter discussions are an unusually good predictor of U.S. House elections. Using a massive archive of billions of randomly sampled tweets stored at Indiana University, we extracted 542,969 tweets that mention a Democratic or Republican candidate for Congress in 2010. For each congressional district, we computed the percentage of tweets that mentioned these candidates. We found a strong correlation between a candidate’s “tweet share” and the final two-party vote share, especially when we account for a district’s economic, racial and gender profile. In the 2010 data, our Twitter data predicted the winner in 404 out of 406 competitive races.

There is more here.

Facts about the minimum wage

…the minimum wage is very much a bottom latter rung for the labor market, which you can see in Meer and West’s evidence that workers frequently transition out of the minimum wage. In their data 59% of workers who earn the minimum wage in one year earn more than it in the next year if they remain employed (5.8% are unemployed and 16.8% have left the labor force). The median wage increase they get is $0.90 per hour, which is a 23% raise. The 75th percentile raise is $2.45 per hour.

That is from Adam Ozimek.

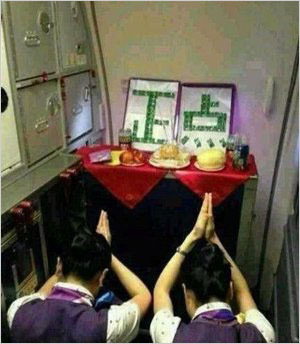

The airline culture that is China

This undated photo shows two Xiamen Airlines stewardesses kneel in prayer at a shrine dedicated to being “on time”.

Here is more. By the way, this is part of the problem:

The latest statistics shows that the flow of air traffic accounts for as high as 40 percent of the total number of flight delays during the first half of this year. And whether the flight could take off in time or not, it depends on the fellowship with the air traffic controller.

Captain Wang Hai said that as long as one crew member on a flight personally knows the air traffic controller, the flight would be given priority to take off in time.

But some air traffic controllers explain that queue-jumping contributes to flights unpunctuality.

“International flights and those carrying important passengers, such as government officials, business tycoons and senior officials in civil aviation, do not have to wait in long queues to take off”, an air traffic controller in south China’s Guangzhou said.

Here is related coverage from The Economist, excerpt:

The first and oldest problem is that China’s armed forces control most of the nation’s airspace—perhaps 70-80% of it. This is especially the case above and around cities, leaving very narrow corridors for aeroplanes to take off, land and navigate nasty weather.

I will once again recommend to you the James Fallows book on aviation in China.

For the pointer I thank D.

August 11, 2013

Assorted links

1. Claims (speculative?) about the culture that is Filipino seafarers.

2. Is the Somalian central bank actually an ATM?

3. S Balachander veena (video). And Jessica Crispin on Pinker on science.

4. Why is Japan in a summer slump?

6. Good interview with the excellent Vaclav Smil.

7. The true origins of Little House on the Prairie.

Is Emile Simpson the new Clausewitz?

The new (November 2012) book is War From the Ground Up: Twenty-First Century Combat as Politics, and yes it is an important work. It is also difficult to excerpt. Nonetheless I especially liked these two sentences about Afghanistan:

This kind of situation, where sides argue tooth and nail over the meaning of every point or action, is typical of unstable interpretative environments, and those environments are in turn produced when people are insecure about who they are, and what they are about. Returning to the analogy of sixteenth-century England, we find that a parallel situation would be the debate over the interpretation of the English translation of the Bible in the 1520s and 1530s.

It is in general extremely insightful on the conflict in Afghanistan, where the author has had three tours of duty. The chapter on the British military campaign in Borneo in the mid-1960s (an oddly neglected historical episode) is also especially good.

Here is FT lunch with Emile Simpson, possibly gated for you. Excerpt:

In Simpson’s view, one of the biggest mistakes the US has made has been to talk about a “global war on terror”, a phrase he describes as silly because it raises expectations that can never be met. “If you elevate this to a global concept, to the level of grand strategy, that is profoundly dangerous,” he says. “If you want stability in the world you have to have clear strategic boundaries that seek to compartmentalise conflicts, and not aggregate them. The reason is that if you don’t box in your conflicts with clear strategic boundaries, chronological, conceptual, geographical, legal, then you experience a proliferation of violence.”

Here is a very positive TLS review of Simpson’s book., where it is described as one of the half dozen essential works on military strategy since World War II.

Dense reading, but definitely recommended.

How would monetarism have fared against the Great Depression?

Paul Krugman has covered this topic a few times lately, most recently here. For instance he writes:

The main point, however, is that we are a very long way from classic monetarism, of the form that says that the central bank can control broad monetary aggregates like M2 at will, and in turn that these broad monetary aggregates determine the course of the economy. That’s not at all true when you’re up against the zero lower bound — which is why Friedman’s analysis of the Great Depression was wrong…

I view Friedman’s position differently and in general I find this discussion would proceed on better terms with more direct quotations from primary sources. On the question of what Friedman actually thought, I will reproduce part of an earlier post of my own:

When it comes to 1929-1931, Friedman favored the Fed a) buying up a lot more bonds, and b) serving as a lender of last resort to failing banks. They are separable but Friedman favored both.

In the Monetary History, Friedman and Schwartz approvingly quote Walter Bagehot about the need to do whatever is required, however bold or desperate, to stop a banking panic. Part of the passage runs like this:

“The way in which the panic of 1825 was stopped by advancing money has been described in so broad and graphic a way that the passage has become classical. “We lent it,” said Mr. Harman [one of the Bank's more senior directors] on behalf of the Bank of England, “by every possible means and in modes we have never adopted before;…”

Here is Charles Goodhart quoting Friedman on why the Fed should have been a lender of last resort to troubled banks. Or see p.269 of the Monetary History, where Friedman and Schwartz explain how it was too difficult for banks to borrow from the Fed at favorable rates in the early 1930s. Or read this Friedman interview.

In other words, had the U.S. followed Friedman’s (later) advice, matters would have gone far, far better. We’re talking about lender of last resort aid to banks, not just printing currency, and we are talking about a time period before the U.S. economy hit a zero lower bound. (In any case LLR functions still work at a zero lower bound.) The money supply would not have fallen by one third or anything close to that.

Now, given 2008 and the like, one can readily argue that Friedman’s proposed actions for 1929-1931 would not have been enough to stave off a major recession. One might also, if only from tone, argue that Friedman did not sufficiently appreciate this point, or that he failed to realize interest rates might have fallen to near-zero anyway. I can’t prove those claims with textual evidence, but I think there is a good chance they are true.

That said, it is incorrect to suggest that monetarism had an impotent, currency-printing, Pigou effect-relying approach to the Great Depression. Had we followed Friedman’s advice, things would have been much, much better, all the more so for the broader world at large. If you doubt this, take a look at Sweden, the country which in the 1930s perhaps came closest to Friedmanesque policy, including no gold standard and floating exchange rates (pdf, and by the way read Bernanke’s FN1: “The original diagnosis of the Depression as a monetary phenomenon was of course made in Friedman and Schwartz (1963). We find the more recent work, though focusing to a greater degree on international aspects of the problem, to be essentially

complementary to the Friedman-Schwartz analysis.”), combined with a less deflationary monetary policy. Their Great Depression was much milder than in most other parts of the West.

In other words, against the Great Depression monetarism would have fared pretty well. Not perfectly, but pretty well.

Addendum: Here is Friedman’s classic 1968 essay on what monetary policy can and cannot do (pdf). And I don’t wish to pick through the various other authors on Friedman vs. Keynes, rather I will refer you to what Friedman actually wrote on the topic when debating a variety of Keynesians and addressing precisely this issue (jstor pdf, maybe this is a better link).

August 10, 2013

Hayek in the 1930s

Paul Krugman on Hayek’s influence in the 1930s:

…back in the 30s nobody except Hayek would have considered his views a serious rival to those of Keynes…

Alvin Hansen reviewing Hayek’s Prices and Production in 1933 in the American Economic Review.

The present volume is, it seems to me, the only book of recent years which at all approaches Keynes’s A Treatise on Money in the impetus it has given to renewed interest and discussion of business-cycle theory.

This in itself is high praise. Altogether aside from the soundness of its

conclusions, the value of the book and its important place in the recent

literature of cycle theory is unquestioned.

von Hayek’s contributions in the field of economic theory are both profound and original. His scientific books and articles in the twenties and thirties aroused widespread and lively debate. Particularly, his theory of business cycles and his conception of the effects of monetary and credit policies attracted attention and evoked animated discussion. He tried to penetrate more deeply into the business cycle mechanism than was usual at that time. Perhaps, partly due to this more profound analysis, he was one of the few economists who gave warning of the possibility of a major economic crisis before the great crash came in the autumn of 1929.

To be clear, it is true that Keynes’s General Theory eclipsed Hayek but to say that Hayek was not a serious rival to Keynes in the 1930s is a Whiggish misreading of the history of economic thought.

Addendum: Don Boudreaux also comments noting that Hicks specifically referred to the great Hayek-Keynes rivalry of the 1930s. See also Greg Ransom’s citations from Hicks and Coase in the comments.

Do note that reading Hayek out of the debate diminishes Hayek but perhaps even more it diminishes Keynes who clearly won over the profession.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 843 followers