Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 304

September 9, 2013

Our new MRUniversity class on International Trade

The class is here and the videos are going up week by week. The summary is this:

This course takes a look at the basic theories of international trade and the consequences of trade in today’s global economy. You’ll have the opportunity to learn more about fundamental ideas such as comparative advantage, increasing returns to scale, factor endowments, and arbitrage across borders. The consequences we discuss include the effects of offshoring, how trade has shaped the economies of China, Mexico, and Korea, when foreign direct investment is desirable, and the history of free trade and tariffs, among other topics. Trade is a topic of increasing importance and this material will give you a better grasp on the theories and empirics as they have been developed by economists.

The iTunes podcasts are here.

I am also using these videos in conjunction with the International Trade class I am teaching, you can find the reading list here.

B.F. Skinner on Online Education

Skinner’s teaching machines didn’t catch on, perhaps because the technology of the time was not flexible enough, but he was right about most of the advantages of teaching machines including immediate feedback both for reinforcement and enthusiasm, individualized pacing, gamification and increases in learning speed.

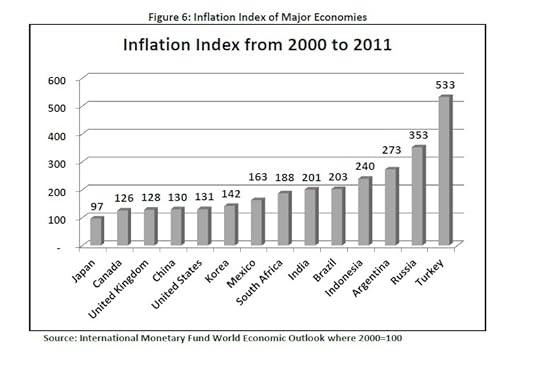

Why are the high growth countries so often the high inflation countries?

That is from this paper by Christopher Balding. South Korea, by the way, during its years of most rapid growth, sometimes had inflation rates of over fifteen percent. I might add that the slow growth countries often see deflation, or deflationary pressures, contrary to what a “naive” supply side model would suggest.

I can think of at least two mechanisms here. First, when economic growth is high and wages are rising rapidly, there may be less public opposition to inflation.

Second, whenever there is lots of growth, markets are forward-looking and the supply of credit outraces the growth of the moment, a’la Long and Plosser (1983). This leads to immediate inflationary pressures.

Of course these two options are not mutually exclusive. In any case, low observed rates of price inflation do not militate against the relevance of supply-side “stagnation-like” shocks, in fact they may point to them.

Addendum: Interfluidity has some interesting speculations on demography and rates of price inflation. Karl Smith offers related comment.

September 8, 2013

Assorted links

1. Blog of a funeral director; “Death keeps no schedule and neither will you.” And here are “Ten Reasons to be a Funeral Director.”

2. The real traveling salesman problem.

3. Insider trading for the literary Nobel Prize?

5. Ten-part Dylan Matthews Wonkbook series on why the tuition is so high.

6. Which new bet did Ehrlich propose to Julian Simon, which Simon did not accept?

7. Miles Kimball on negative interest rates.

What I’ve been reading

1. Roger Osborne, Iron, Steam, and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution. A good popular overview of the British industrial revolution, focusing on inventors, coal, and engineering innovations.

2. John D. Barrow, Mathletics: A Scientist Explains 100 Amazing Things About Sport. I found half of this book to be fun, a pretty high hit rate given its style of many short chapters. I learned how basketball players create the illusion of “hang time” (their bodies are falling parabolically, but their heads don’t have to be), that Mark Spitz would not qualify for U.S. Olympic trials today, and why the best discus throws are into the wind.

3. Eleanor Catton, The Luminaries. I’ve read 200 pages of this 800 pp. novel and am not sure whether I should continue. It is set in 19th century Otago, New Zealand, it focuses on the obscure criminal activities of some migrant derelicts (and elites), and it has superb writing and plot. It could be one of the books of the year. But do I care? Perhaps this FT review nails it.

4. The Silent Wife: A Novel, by A.S.A. Harrison. Fun, a good short plane read, you toy with the idea that the guy really does deserve to die.

5. The Divine Comedy, by Dante and Clive James. This really is a co-authored work. It is the most beautiful poetic treatment of Dante in the English language, yet I fear it is no longer Dante. I would prefer it if the book were simply marketed as Clive James. In fact I fear it will displace “the real Dante” in my memories. I am conflicted, and may not finish it for this reason, besides I already know how it ends. Some of you will love this, however.

6. Philip Pullman, His Dark Materials. I had never read this trilogy before, thinking it was a “fun but not essential” story for teens. In reality it is as close as we moderns are going to get to Milton, Blake, and Dante. For me it is one of the better literary creations of the last twenty years.

A dearth of investment in young workers

Here is my latest New York Times column, excerpt:

For Americans aged 16 to 24 who aren’t enrolled in school, the employment picture is grim. Only 36 percent are working full time, down 10 percentage points from 2007. Longer term, the overall labor-force participation rate for that age group has dropped 20 percentage points for men and 14 points for women since 1989.

This lack of jobs will damage the long-term careers of a big chunk of the next working generation. Not working after you finish school very often means missing out on developing the skills and habits that will serve you well later on. The current employment numbers are therefore like a telescope into the future labor market: a 23-year-old who is working part time as a dog walker, yoga instructor or retail clerk may be having fun, but perhaps will receive fewer promotions as a 47-year-old.

And:

Employers appear to be more risk-averse, more concerned about overhead costs and less willing to invest in developing young workers’ skills. And that seems true across a wide variety of sectors.

In the legal profession, for instance, there is less interest in hiring junior associates and grooming them for partner status. Colleges and universities are often more interested in hiring adjuncts than tenure-track young faculty members. And publishing houses, instead of providing a big advance upfront and investing in young authors over a series of books, now expect many writers to earn their share of a book’s revenue through royalties.

There are further relevant points in the article. And here is an FT article about more and more young British people living at home.

Here is a compelling visual from Wonkbook:

September 7, 2013

The FTC vs. the DC Taxi Cab Commission

The FTC recently released a letter supporting competition in the DC Taxicab industry:

[The FTC] staff respectfully suggests that DCTC carefully consider the potential direct and indirect impact of its proposed regulations on competition. We believe that unwarranted restrictions on competition should be avoided, and any restrictions on competition that are implemented should be no broader than necessary to address legitimate subjects of regulation, such as safety and consumer protection, and narrowly crafted to minimize any potential anticompetitive impact.

In response, taxi commission chair Ron Linton suggested that Uber had a hand in writing the FTC letter. Regulators can sometimes be captured but not by firms launched in 2010! FTC commissioner Joshua Wright (formerly a colleague at GMU law) responds in the Washington Post with a telling point:

Linton’s uninformed comment tells us more about the commission’s approach to regulation than about the FTC’s. According to The Post, Linton described the commission’s regulatory role to that of a referee of competing interest groups.

Indeed, what competing groups is Linton talking about? Might it be producers and consumers? And what does it mean to “referee” the competition between producers and consumers if not to raise prices and incumbent profits?

*The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty*

That is the new Nina Munk semi-biography of part of Sachs’s life, which I consider to be a follow-up to Hayek’s The Counterrevolution of Science. It is an illuminating look at the limits of engineering approaches to social and economic problems, and the nature of human motivation, as told through the medium of one very colorful (and irascible) life. The narrative is entertaining, and it does document a shortage of meta-rationality in its major subject, but still this book is not fair to the positive side of the story. A simple question: how many people have much better lives because of Sachs and his efforts on behalf of economic liberalization and also against poverty? I suspect the number is high.

You can buy the book here. There is an excerpt from the book here. Here is the book’s home page. Here is a WSJ review. Here is a Joseph Nocera review. Here is our MRU video on Sachs’s Millennium Villages Project.

Assorted links

1. The gender gap in economics (pdf).

2. Interview with John Haltiwanger on job creation and destruction (pdf).

3. Will the winner of Carlsen-Anand simply be a matter of luck?

4. Sociology to economics translation guide (pdf).

5. The incredible shrinking labor force is not just demographics.

Firefighter Hysteresis

The number of fires is down but the number of career firefighters is up, as I showed last year in my post firefighters don’t fight fires. Leon Neyfakh of the Boston Globe covers the situation in Boston:

…city records show that major fires are becoming vanishingly rare. In 1975, there were 417 of them. Last year, there were 40. That’s a decline of more than 90 percent. A city that was once a tinderbox of wooden houses has become—thanks to better building codes, automatic sprinkler systems, and more careful behavior—a much less vulnerable place.

As this has happened, however, the number of professional firefighters in Boston has dropped only slightly, from around 1,600 in the 1980s to just over 1,400 today. The cost of running the department, meanwhile, has increased by almost $43 million over the past decade, and currently stands at $185 million, or around 7.5 percent of the city’s total budget.

Later, I am quoted:

Alex Tabarrok, an economist at George Mason University who discussed the fire statistics on the blog Marginal Revolution, explains it in terms of what’s called the “March of Dimes problem.” When polio was defeated, the March of Dimes, started under Franklin Delano Roosevelt to combat the disease, suddenly had no reason to exist. “They were actually successful, and it was something they never planned for,” said Tabarrok. “But instead of disbanding the organization, they set it onto a whole bunch of other tasks…and so it’s kind of lost its focus. It’s no longer easy to evaluate whether it’s doing a good job or not.”

This, in Tabarrok’s view, is what happened to the country’s fire departments: At a certain point, they became an organization in search of a mission. “So they ended up doing things they’re not necessarily the optimal people to do, like responding to medical emergencies.”

Some cities are trying to change but as I said in my original piece, “it’s hard to negotiate with heroes”. The situation in Toronto illustrates. Paramedics were recently assigned to more emergency calls at the expense of firefighters who have responded with photos ops in front of burned homes and threats that if their budget is cut children will die. Not wanting to lose their newly found responsibilities, the paramedics have responded with a campaign of their own leading to an awesome cat fight between the two agencies.

I enjoyed Margaret Wente’s conclusion:

A powerful combination of fear-mongering and hero worship has made Canada’s fire departments largely immune to budget cuts. As a consequence, the citizens are getting hosed.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 843 followers