Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 302

September 13, 2013

Assorted links

1. Which is the only nation to start the Olympic games as one country and finish it as another?

2. Profile of economist Heidi Williams and her work on genomes and IP rights.

3. The benefits of international adoptions.

4. Paul Krugman is right, the Girardian Orphan Black is a very good TV show. And here is Krugman on Tobin and tapering.

5. Orangutans plan their trips (hail Lord Monboddo!)

6. Truthdig reviews Average is Over, and will computers paint as well as humans?

Can the Internet of Everything bring back the High-Growth Economy?

That is the new paper by Michael Mandel, interesting throughout, here is one excerpt:

…we estimate that the Internet of Everything could raise the level of U.S. gross domestic product by 2%-5% by 2025. This gain from the IoE, if realized, would boost the annual U.S. GDP growth rate by 0.2-0.4 percentage points over this period, bringing growth closer to 3% per year. This would go a long way toward regaining the output—and jobs—lost in the Great Recession.

And what is the Internet of Everything?:

The Internet of Everything is about building up a new infrastructure that combines ubiquitous sensors and wireless connectivity in order to greatly expand the data collected about physical and economic activities; expanding ‘big data’ processing capabilities to make sense of all that new data; providing better ways for people to access that data in real-time; and creating new frameworks for real-time collaboration both within and across organizations.

Read the whole thing.

Why Michael Woodford supports monetary tapering (Kaminska wins)

In an excellent, follows up on my original question, there should be more of this kind of reporting piece, Matthew Klein writes:

“For Woodford, the most important point is that the Fed’s balance sheet cannot keep growing without imposing costs on the financial system and broader economy — even when inflation is low and unemployment is high. While Woodford didn’t explicitly tell me what those costs were, a possible explanation can be found in this brief passage from the paper he presented at last year’s Jackson Hole Economic Symposium:

An increase in the safety premium obtained by making “safe assets” (in the relevant sense) more scarce would in itself be welfare-reducing. If Treasuries provide a convenience yield not available from other assets (including bank reserves), then reducing the quantity of Treasuries in the hands of the public reduces the benefits obtained from this service flow.

In other words, Treasury bonds are uniquely useful for savers. When the Fed makes these securities more expensive — or restricts their supply through asset purchases — the central bank harms regular savers without doing much to boost the broader economy. Moreover, the relative scarcity of newly-issued Treasury bonds has been causing havoc in the repo markets.

Woodford suspects that the Fed agrees with him. In fact, he thinks that the pace of tapering will (and should) be determined almost exclusively by the size of the balance sheet rather than the health of the economy:

This explains, in my view, how it was possible for Fed officials to indicate that it would likely be time to begin slowing the rate of purchases later in the year, even while admitting that it was not yet time for the tapering to begin last spring. The point was not so much that they felt confident that they could already predict labor market conditions in the remainder of the year, but rather that they could already predict how large the balance sheet would have gotten by later in the year — and they knew that, barring substantial unexpected developments with regard to economic conditions, they would be concerned by then about allowing the growth of the balance sheet to continue too much further.

Hopefully this explains why someone known as a monetary “dove” can support tapering without being inconsistent.”

TC again: To keep the difference between Klein and Woodford especially clear, I have refrained from indenting the block of material as a whole.

Here is Izabella Kaminska on collateral shortage.

September 12, 2013

Wilson.cat and the movement for independence for Catalonia

The Catalonian “human chain” was yesterday, and it drew hundreds of thousands of people, a large number for a single region. According to the Washington Post, it was more than one million people.

If you would like to read more on this — by economists and other social scientists — Wilson.cat is one intellectual resource for independence. The site represents writings of prominent scholars favoring independence — or at least an informed referendum — for Catalonia.

I am surprised this initiative is not receiving more attention. If you were to ask in which ways economists today are having the most influence on the world, this movement would be close to the top of the list. Among the economists involved are Andreu Mas-Colell, Pol Antràs, Jordi Galí, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, all of whom are extremely well known in the profession.

Personally, I am still waiting to hear why Catalonian independence would not bring the fiscal death knell of current Spain, and thus also the collapse of current eurozone arrangements and perhaps also a eurozone-wide depression. Otherwise I would gladly entertain Catalonia as an independent nation, or perhaps after the crisis has passed a referendum can be held. When referenda are held during tough times, it is often too easy to get a “no” vote against anything connected with the status quo.

Is the view simply that “now is the time to strike” and “it is worth it”? Obviously, an independence movement will not wish to speak too loudly about transition costs, but I would wish for more transparency. Or is the view that Spain could fiscally survive the shock of losing about twenty percent of its economy, with all the uncertainties and transition costs along the way? That could be argued, but frankly I doubt it, OMT or not, furthermore other regions would claim more autonomy too. An alternative, more moralizing view is that the fiscal problems are “Spain’s fault in the first place” and need not be discussed too much by the pro-independence side, but I am more consequentialist and marginal product-oriented than that.

This piece, in Catalan, does cover the fiscal implications of debt assumption for an independent Catalonia. The site also links to this somewhat spare piece by Gary Becker, but I still want more of a discussion of the issues raised above.

Keep in mind that two clocks are ticking. The first is that education in Catalonia is becoming increasingly “hispanicized,” the second is that as economic conditions in Spain improve, or maybe just become seen as a new normal, getting a pro-secession vote in a referendum may become harder. It doesn’t quite seem like “do or die” right now, but overall time probably is not on the side of Catalonian independence.

If anyone connected with the independence movement could point me to source materials addressing my questions, I would gladly cover it more on MR.

Here is Edward Hugh on the Catalan Way explained. And here is more from Hugh.

The problem

One reason that many Americans believe Medicare does not contribute to the deficit is that the majority thinks Medicare recipients pay or have prepaid the cost of their health care. Medicare beneficiaries on average pay about $1 for every $3 in benefits they receive…However, about two-thirds of the public believe that most Medicare recipients get benefits worth about the same (27%) or less (41%) than what they have paid in payroll taxes during their working lives and in premiums for their current coverage.

Here is more, via Amitabh Chandra.

Assorted links

1. Is there a fiscal cliff in Japan? And what macro do we teach at the Principles level?

2. What is, was, and will be popular?

3. Is having a lot of children now a sign of status?

4. In the S&P 500, the average company lifespan is getting shorter. And the economics of new re-translations.

5. What if they made a trailer today for Monty Python and the Holy Grail?

6. Angus on the Pigouvian fate of the University of Florida economics department.

Publication day for *Average is Over*

There is an NPR segment with Steve Inskeep here, with text, the audio goes live at 9 a.m. I also am part of this BBC segment, with Rohan Silva.

You can buy the book on Amazon here. On Barnes and Noble here. On Indiebound.org here. And from Penguin here. The Diane Coyle review is here.

Sinister Statistics: Do Left Handed People Die Young?

In 1991 Halpern and Coren published a famous study in the New England Journal of Medicine which appears to show that left handed people die at much younger ages than right-handed people. Halpern and Coren had obtained records on 987 deaths in Southern California–we can stipulate that this was a random sample of deaths in that time period–and had then asked family members whether the deceased was right or left-handed. What they found was stunning, left handers in their sample had died at an average age of 66 compared to 75 for right handers. If true, left handedness would be on the same order of deadliness as a lifetime of smoking. Halpern and Coren argued that this was due mostly to unnatural deaths such as industrial and driving accidents caused by left-handers living in a right-handed world. The study was widely reported at the time and continues to be regularly cited in popular accounts of left handedness (e.g. Buzzfeed, Cracked).

What is less well known is that the conclusions of the Halpern-Coren study are almost certainly wrong, left-handedness is not a major cause of death. Rather than dramatically lower life expectancy, a more plausible explanation of the HC findings is a subtle and interesting statistical artifact. The problem was pointed out as early as the letters to the editor in the next issue of the NEJM (see Strang letter) and was also recently pointed out in an article by Hannah Barnes in the BBC News (kudos to the BBC!) but is much less well known.

The statistical issue is that at a given moment in time a random sample of deaths is not necessarily a random sample of people. I will explain.

The statistical issue is that at a given moment in time a random sample of deaths is not necessarily a random sample of people. I will explain.

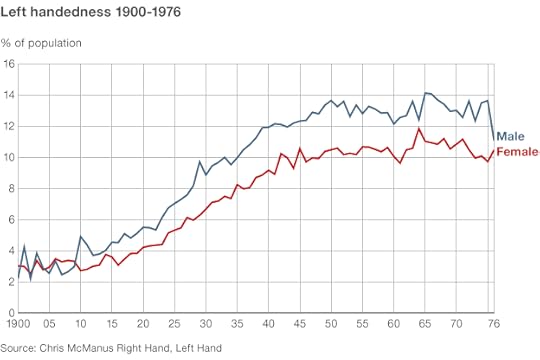

Over the 20th century, left handers have increased as a fraction of the population. Left handedness may be relatively fixed as a genetic matter but in the earlier decades of the 20th century children were strongly discouraged from exhibiting left-handedness. As a result, many “natural” lefties learned right-handed behavior and identified as right-handed adults. Over time, however, the cultural suppression of left-handedness declined and the proportion of adults exhibiting left-handedness increased, as the figure, at left, illustrates (fyi, I believe British data).

Now suppose you take a random sample of people who died in 1990. In this sample, some people will have died old and some young. Among those those who died old, however, fewer people will be identified as left-handed because the old grew up in a time when left-handedness was suppressed. As a result, the old deaths in your sample will tend to be have more right-handed people and the young deaths will tend to have more left-handed people causing you to incorrectly conclude that left-handed people die younger. Studies show that this statistical artifact can easily explain a 9 year difference in apparent mortality rates.

To make this crystal clear consider the following thought experiment (offered by Chris McManus). Imagine you take a sample of people who died recently and asked their surviving family members, Did the deceased ever read the Harry Potter novels? One would clearly find in such a sample that those who died tragically young (at age 12 let’s say) would have been much more likely to have read Harry Potter than those who died in their 90s. Despite what some might argue, however, we should not conclude that Harry Potter kills.

Hat tip: Tim Harford.

September 11, 2013

The assumption of “free disposal,” as applied to children

This rather horrifying link has been making the rounds on Twitter, here is the bottom line:

When a Liberian girl proves too much for her parents, they advertise her online and give her to a couple they’ve never met. Days later, she goes missing.

The practice is called “private re-homing,” and it seems plenty of it goes on, and without government scrutiny (in many cases a simple notarized statement may accompany the handover).

Maybe I’ve read too much Walter Block ($2.99 on Kindle) in my day, but well, um, well…you know. Is the solution to make the initial adopting parents keep the girl? That seems doubtful. Are the children better off being sent back to an orphanage rather than being re-gifted? Possibly so, but this is not obvious. From a legal point of view, for sure. But as for the utilitarian and Benthamite angle? A lot of evil parents might keep their newly adopted children (and to the detriment of those children) because return to the orphanage could be bureaucratic, costly, and also humiliating, at least compared to giving them away rather rapidly over the internet.

Should we screen adopting parents more rigorously, so as to prevent lemon parents from adopting in the first place? Well, maybe, and if you read the article you will see some cases where better upfront screening would have been highly desirable. But tougher screening as a general rule? I don’t know. Adoption is already costly and bureaucratic, it is on average welfare-enhancing, and maybe we can’t easily screen out most of the lemon parents anyway. Etc.

On the other side of the issue, limiting free disposal likely would improve the average quality of adopting parent through positive selection. Quite possibly that effect will predominate but I would ask for the same standards of evidence here that we apply to other policy decisions.

I say we don’t yet know the proper policy response to this issue, but it’s worth thinking this through with more rigor than a simple “mood affiliation” response might suggest.

Assorted links

1. Markets in everything. And a computer fit for the Amish.

2. “Our goal is to make Bitcoin truly grandma-friendly.”

3. Good post on job ladders from Dube’s new blog.

4. Ant trade and symbiosis. And economics, Adam Smith, and psychoanalysis.

5. Henry on the tech intellectuals (pdf), or the web link here.

6. Driverless cars are moving closer to reality.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 843 followers