Nimue Brown's Blog, page 396

March 29, 2014

One Hundred and One Pagans

Once upon a time, one hundred and one Pagans came together. So far as anyone knows, none of them were at any risk of being turned into fur coats, although some of them were indeed resplendent with fine facial hair. Actually, anyone who has ever tried to organise anything Pagan will know that allusions to puppies are way off the mark. It’s like herding cats. It is therefore worth acknowledging the heroic scale of the feat in which Trevor Greenfield organised one hundred other Pagans to write a book.

My role in that book seemed small at the time – although I felt deeply honoured to have been included. I wrote a piece on prayer and meditation within Paganism. Then, as is so often the way of it, everything went quiet. A lot of time in the process from writing to publishing does not involve the author at all. Even when there are hoards of them. I didn’t interact with the people who were commenting on my bit, and it wasn’t until I came to read the book that I found out how they’d undertaken to extend and explore those ideas.

For me, slowly reading the entire book has been a much more exciting process than writing my bit of it. I know what I think, no great surprises there! Seeing the diversity of opinion and practice, the freedom from dogma, and at the same time the innate coherence is a powerful experience in its own right. Paganism is incredibly rich, reflective and creative and within it all kinds of traditions are establishing and flourishing. While no book could ever do justice to the full diversity – because you’d never get all of us into one book – in that range of one hundred and one Pagans from around the world, I think a real sense of us as a religious group comes through. It’s a group I am very proud to be a part of.

Reading the book also had me wondering to what extent this is an artefact of our times, a moment of our history. Twenty years ago no one could have pulled this together, Pagans were secretive and relied far too much on the post. We didn’t have that flow of open and international communication. What will this book look like in fifty years time, or a hundred? I feel we’ve created a record, a snapshot that future Pagans might find useful in charting our progress.

I rather hope those Pagans will look back at Paganism 101 and find it touching, and see in it all the early signs of the great things that followed, and shake their heads at all the things we did not have and were not doing, and had yet to imagine. And then find 101 voices for their own moment in time, and do it all again.

March 28, 2014

Speaking Greenly

The most difficult, and therefore also the most important people to try to talk to about green issues, are the ones who do not believe in it. Those people who do not grasp the idea of ecosystems, and have no sense of a need for natural balance. Those people who see nature as merely a backdrop, or as a set of resources to exploit for personal benefit. Many of them do not seem to grasp that those resources are finite, even, and want to keep using as though it is viable to do as they please forever.

They have ways of dealing with people like me. We’re lefty tree huggers, and that agenda of protecting the environment is clearly also about benefiting the undeserving poor. Those who have no sense of relationship with the world tend also to have no sense of relationship with most of the people inhabiting it, either. Or we’re middle class idiots with no idea what the workers really need. (Yes, I get both). We can be written off as alarmists, as nutty, fringe types with no idea of how the real world works. Never mind that thousands of scientists agree with the green position and that most green thinking is shaped by research. We’re away with the fairies, and by invalidating us from the outset, it’s easy to ignore us.

How do we begin to overcome that? How do we break down those layers of wilful ignorance? How do we get people to listen when they’ve stuck their fingers in their ears and are chanting “I can do what the hell I like and it will all be fine”?

Faced with this, frustration is inevitable, and anger is not unthinkable. The desire to scream back “you idiots, we do not have time for this nonsense” is huge. That will not change their minds or get them onboard, and while they seem to infiltrate all levels of politics and big business, shouting at them isn’t enough. Shouting at them is just a way of letting it all continue.

I spent ages arguing with someone yesterday. I say ‘arguing’ but that implies exchange. I was trying to express, without aggression, reasoned positions and arguments. His side of the debate looked like “DUH” and “WAKE UP TO HOW THINGS REALLY ARE” and yes, most of it was all caps. He didn’t want to hear, and could not muster a detailed explanation of his own ideas, but, never mind that, he wanted the world run along his lines. Who need experts when you’ve got a loud voice and an opinion? I’d like to think he went away and thought about what I said, but I doubt it.

How do people not see the connections? That we need the bees and that pesticides which kill bees are therefore a real problem. That we need clean drinking water and that poisoning the water to get the last dregs of oil, is madness. That resources are finite and we’d need three planets or more if we wanted to keep going as we are. These are not complex ideas, but apparently they are difficult. I saw a UKIP politician yesterday talking about ‘protecting our lifestyle’. Ah yes, we must keep destroying the world so that we can carry on spending lots of time commuting to and from work, barely seeing friends or family in order to do things far too many people find dull or meaningless, so that we can sit in front of brightly lit boxes and watch other people pretending to live for a few hours every day. That lifestyle, right? That glorious pinnacle of human culture and achievement.

No, I have no idea how to begin to persuade anyone who thinks that way, that they may be just the teensiest bit wrong.

March 27, 2014

Vote for the Conservation of the Glorieta Stream

© Jesús Ortiz

Guest blog by Adam Brough, a member of CEN CEN is an association in Tarragona, Spain working for the conservation and improvement of habitats and biodiversity.

One of our projects is the conservation of the Glorieta Stream, which became a finalist in the category of Alpine projects, and could receive support from EOCA. But this depends on a public vote accessible to anyone over the Internet. The aim of CEN’s proposal for the Glorieta “is to guarantee the long term conservation of the Glorieta stream headwaters. The site is protected by the Natura 2000 Network of the Prades Mountains. The deep pools, long waterfalls, and turquoise waters are admired by thousands every year, including those that come specifically to hike and canyon. The area is rich in endangered species such as the white clawed crayfish, red tailed barbell and white throated dipper. The main threats are the increasing numbers of visitors, litter, graffiti and damage caused by visitors, and exotic invasive plant and animal species. Through CEN, this project will organise several clean up events, remove invasive species and raise awareness amongst local schools and businesses about the importance of the area. It will also negotiate with groups to regulate canyoning and fence off the most sensitive areas and highlight ‘safe’ routes and responsible behaviour.”

To vote for and get more information about the Glorieta stream visit this page: http://www.assoc-cen.org/Glorieta_eng.php

To get more people voting we ask that you pass this on to friends, family and other contacts through email, social networking sights, blogs, etc.. Thanks!

About EOCA’s project voting: http://outdoorconservation.eu/project-info.cfm?pageid=19 About CEN: “The association for the Conservation of Natural Ecosystems (CEN) is a non-profit organisation, whose objective is to work for the improvement and conservation of habitats and biodiversity. “…the CEN association develops projects to study and conserve natural ecosystems and makes a serious effort to raise the awareness of citizens of the necessity to respect the environment.” More information can be found on their website, in English here: http://www.assoc-cen.org/index_eng.php Adam Brough is a British expat living in Spain. He’s always been interested in nature conservation from a young age, studying it in Sussex, England. As well as being a volunteer and board member of CEN, he lives and works in a private ecological project, Biosfera2030. He is a member of OBOD, studies psychosynthesis and ecopsychology, and regularly writes about his life and reflection in his blog, Druid in Training: http://www.druidintraining.wordpress.com/

If you are able to reblog this, please do as there aren’t many days left to get the word around.

March 26, 2014

Slightly out of my head

I’m fascinated by the way in which illness affects my brain, especially anything that leaves me feverish. Having had a round of this over the last few days, it’s been one of the few things reliably on my mind. Brains are of course a heady mix of biology and chemistry (plus inexplicable consciousness) and the limits of what it’s possible to do with them has all kinds of implications.

Monday night there was a scary thing. The kind of thing that in normal circumstances, would have given me a panic attack. I felt fear as a more intellectual thing, and then my body just didn’t. There was no spare energy with which to panic, no means of working up a rush of adrenaline, it just wasn’t happening. The ill state of my body neatly cancelled out the ill state of my brain, leaving me with nothing more dramatic than an ‘isn’t that interesting’ and a desire to try and sleep it all off.

Various fevers have convinced me (temporarily)that I know the secrets of the universe, am dying, that reality is just lots of little boxes blending together, that the bed is a boat, that the bed in a boat is not in a boat after all, and all manner of random things. Recognising feverishness, it is important to check these things with kind, non-feverish people who can confirm or deny as appropriate. It’s useful, when hallucinating for example, to know that that the faces in the curtain are not, really speaking, there. Knowing I’m ill and being able to ask and get a check on where consensus reality is saves me from getting on facebook and announcing that I’ve seen how it really is… when really it’s the flu speaking.

Various bouts of depression and anxiety have convinced me (also temporarily) that I am doomed, ought to die, that the universe is innately hostile, that nothing I do can ever work, and a whole bunch of other profoundly unhelpful things. However, depression and anxiety do not show up with overt physical symptoms that alert other people to the problem. It’s still brain chemistry miss-firing though. A check-in with consensus reality is just as valuable in this context as it is when there’s fever conjuring little green men into your sock drawer.

I have a lot of questions about how real reality really is. Not helped by recently listening to Brian Cox on radio 6, talking about the infinite possibilities of the multiverse. I was feverish at the time, but am reliably informed he did say things that suggest Douglas Adams was right, and therefore somewhere there really are sentient mattresses… but I digress, which is easy when the mind is a bit wobbly. What enables us to get by passably from one day to the next is having some agreements about what reality is, what is real and how to think about it. Illness can distort and change it – whether we get more or less real when out of our heads is really secondary to the certainty that we do get less functional. Checking that gravity works, and that the conviction you can fly may be flawed, is, for example, a good investment. I regularly dream I can fly, and fever can break down the clear lines between awake and asleep.

If you don’t test your impressions, then you keep your own private take on reality locked safe inside. No one can see it, comment, ridicule, or deny it for you. This may be fine right up until you jump out of the window. The person who can be trusted to recognise when you’re ill and out of tune with the consensus, is a very good friend to have, especially if you are prone to an unwellness of the head. Not the person who calls you stupid and deluded – thus actually confirming your fears whilst making it impossible to talk about them. The person who can say “it probably looks that way because you’ve fallen down a hole, other realities are available” is a great help. Keep silent and it is much easier to believe that the hole is real, and all the people acting as though they are not in a hole, are insane. If you mention, and it turns out everyone else is stood in the same hole after all, you know it’s not you, and you’ve got a team seeking an escape route, and that’s better. It gives you unions, pressure groups, revolutions…A bit of consensus reality can go a long way sometimes.

March 25, 2014

Escaping the Money-Versus-Creativity Trap

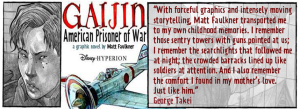

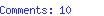

Guest blog by Matt Faulkner

I’m a children’s book illustrator and author and from time to time it is my pleasure to visit schools and share my work with children. Recently I’ve noticed that kids are questioning the fact that I share the business aspect of what I do during my presentations. Now, I’m fairly sure that this is not some sort of trend in the awareness of children concerning money. It’s probably just me and the sensitivity I’ve developed over the past 30 years of my being an illustrator/author.

And yet, yesterday it happened again.

A 5th grader asked-

“When all is said and done, what’s more important to you- getting money or being creativity.”

I’ll tell you what I said to him in a moment.

But first I want you to know that I have a purpose in presenting the issue of artists and writers acquiring income when talking to kids. It’s my belief that there is a real disconnect in our culture regarding those who choose a creative vocation and many of those who choose something else. I know I’m not saying anything radical here. It’s just that I’m tired of this disconnect and wish to do something about it.

For many reasons, we as a society seem to insist that our creatives remain “pure” and not concern ourselves with worries of money. If a creative should discuss money, we tend to lump her/him into a slimy category of all those others who give up their their virtue for gold- such as drug dealers and lobbyists. The crazy part of this is that, if we, as creatives, actually buy into this societal “money-versus-creativity” trap (e.g. starving artist is good, thriving artist is false) why is it that we don’t demand that our culture support us? I mean, somebody’s got to foot the bill for all the wonderfulness we bring into the world, right? For instance, we could demand that society give all creatives tax abatements, free housing, free chocolate, free lunch meats even. If things were managed this way then creatives could be über-creative (maybe) and yet never have to sully our pristine selves with dirty dollars. Still a crappy situation but at least we’d get free chocolate and lunch meats. So, until we accept that being creative is as natural a vocation as any other, requiring hard work, sensibility, discipline and, dare I say it, a desire to pay the rent on time, then we shouldn’t complain when we get paid a pittance and find ourselves stuffed into a cramped box.

And that’s why I talk about how I make money to kids. Because it’s good for them to know that working as an artist is a job like any other. A great job, but still a job.

So, my answer to the 5th grader?

“Yes.”

The 3rd graders up front didn’t like my response.

“That’s not an answer!” they hollered.

I smiled and did another drawing for them, then gave the sketch to one of the kids. I also smiled and thanked the school librarian when I was handed my honorarium check.

As I re-read what I’ve written above I think my answer to the youngster could appear trite. Here’s the thing though- I had just given an hour long presentation which I believe clearly showed my motivation; in short- I love to draw, paint and create. And just so you know, the message- do what you love and the money will follow- is a big element of my talks. I think the kids very much get these points. Yet, as I’ve pointed out, I also let them know that I like money. I tell tham that I believe money to be a tool and that I don’t feel that being creative and making money are exclusive efforts. So, with that said, I don’t know what that young man’s motivation was in asking the question. But I do find it interesting that this question is even asked, whether in a situation like this by a child or at any time by anyone. Why do we even question the motivation of a creator who wishes to make an income? Is it a bad thing when anyone makes a living or even gains wealth by doing what they love to do? Or is it just artists who are bad when they make a living off of their work? Lastly, is it a bad thing that we are instilling this prejudice in our children?

And btw, my private helicopter ran out of Perrier on the way home. Boy, was that ever frustrating.

Thanks for taking the time to read my thoughts on the subject.

Sincerely,

Matt Faulkner

www.mattfaulknerblog.blogspot.com

www.mattfaulkner.com

https://twitter.com/MattFaulkner1

March 24, 2014

Communities of care

Life is sometimes very hard indeed. The balance varies for each of us to outlandish degrees. While access to money can ease the other crap into being more bearable, even wealth can be stripped away by misfortune. Nothing is certain. This is why community is so important. It is in connecting with each other, to share the good and the bad alike, that we make life bearable. This can mean exposing ourselves to more pain as we open our hearts to the suffering of others, but it is utterly worth it.

In sharing, we learn, which can make us better prepared for our own setbacks. In sharing, we develop resilience and resources to tackle problems. We develop banks of knowledge and insight so we’re not individually re-inventing the wheel as the same old problems come round again. Very little is new. Death and sorrow, poverty and exploitation, tyrants in power and the commons in peril – I could sing you songs from a hundred years ago that tell all the same stories.

There is an approach that resents and resists other people speaking from this distress. There are many ways to silence discomfort. Ridicule, suggesting it is ‘over the top’ making comparisons to those who are, by some undisclosed measure ‘much worse off’ we can make people in pain shut up. This means we do not have to feel any responsibility for helping them. The consequence of this is to increase social isolation and to increase misery by a number of means. Today I was told that by expressing when I am unhappy and getting support, I have got into a self-perpetuating cycle that encourages me to stay in a place of pain rather than deal with it. Nice one! By this means am I to be shamed into silence, and into isolation, whilst being told I am being helped. It is bullshit, and needs labelling as such. How do we handle, as communities, the people who undermine community? One for another day perhaps.

When we work as communities to support each other, what happens is that everyone who today takes a supporting role, gets to feel useful and valuable. You are holding someone up, this is massively useful and valuable. It also demonstrates your membership of the community, expressing and reinforcing bonds of connection. You know, that when you get into trouble, the same thing will happen – people will rally round with kind words at the very least. There may be useful advice, wisdom, practical help, insight, opportunities – all of which could not have flowed to you if you had not expressed distress and need in the first place.

We all have off-days and periods of crisis. It is part of being alive and being human. If I sit here telling you about how great my life is, because I’m published/married/a Druid/have good karma/think positive thoughts and I create an illusion of joyful perfection, that could easily make it seem that there is a reason why my life is damn near perfect, and your isn’t, and the reason is you. That’s also bullshit, and damaging. If I own my crap, and own that crap happens randomly to us all, you know that I am not somehow magically better than you, and there is no innate failure in you that explains why things do not go so well sometimes. When you own your crap in turn, I am reminded that there’s nothing uniquely wrong with me, I am about as flawed and confused as the next person, and that’s ok. We’re allowed. I’m not faultlessly compassionate or infallibly wise. I make bad calls. We all do.

We are all, also now and then graced with moments of shining awesomeness. If you’re in an alienated culture where you can’t mention the shit, but you dare to mention the glorious success, the odds are some irate bastard will knock you down for that, too. In a culture where knocking people down is normal, anything that isn’t beige and forgettable makes you a target. Just look at how we treat our celebrities! In a real community, there is room for the sorrows and the celebrations, for the triumphs and disasters, for the bad days and the good ones, in whatever mix we get them. There is room to delight in each other, be proud of each other, support, enable, nurture and help each other through good times and bad times alike.

If you’re sharing a word, a thought, a moment, you are part of that community for me and I really appreciate it.

March 23, 2014

Other people’s rituals

Ritual is a shared, community activity, but often it’s also very personal. Other people’s rituals, even when technically in the same tradition, can therefore feel a bit strange. Quirks of ordering, precise language use and the like are either familiar and comfortable, or they aren’t. For example Druid Camp uses ‘know that you are honoured here’ where many would use ‘hail and welcome’ and because I deliberately use neither, I can be easily thrown by both.

There are many good things about leaving behind our own ways of ritual and pottering along to see how it works for others now and then. It’s a chance to connect, to learn and to see our own ritual habits from a different perspective. This is all good, so long as we respect the right of our host to undertake ritual in the way that they see fit. That in turn can make for some interesting balances between meaningful participation, honouring the methods of the host and being comfortable with what you do and say.

Striking that balance can be challenging enough with people doing their Druidry a bit differently. It’s harder again when you go into a different Pagan group and do not know the forms exactly, but this is nothing compared to going outside of Paganism altogether, and that’s something we often have to do. The dominant religion for celebrating rites of passage remains the Christian Church, in all its vast and disorientating diversity. The odds are that people who matter to you will want Christian rites of passage and will want you to be there.

I don’t like pretending to go through the forms of a religion I do not honour – that seems innately disrespectful. Failing to participate in any way that is disruptive, would be an unkindness and an insult to the people who have invited me. I try to find my balances around quiet presence and witnessing and very understated non-participation. It helps that I am entirely out as a Pagan, so no one who matters to me has unrealistic expectations about what I can be called upon to do.

With most rites of passage, it is enough to go along, witness and be happy for the people involved. Afterwards, there will probably be something involving cake and a chance to do something more personal. The exception is funerals. All of my immediate ancestors thus far have had Christian burials, or Christian crematorium services. These I find tremendously difficult. A funeral is an important moment in the grief process, and the time of collectively undertaking to say goodbye to the departed. Shared tears and mutual support and, for the Christians, reassurance about the eternal love of God, the eternal life in Jesus Christ, Heaven, forgiveness for sins and the such. All concepts rooted utterly in Christian faith, and likely to be meaningful to Christians. Where the departed, and most of the bereaved are Christian, there is no doubt about it – this is the right thing to do.

Where the dead one was Christian, I can hardly saunter off and have a little Pagan moment for them at my leisure – that would not be respectful and it wouldn’t feel right. What it leaves me with are some practical challenges about how to work through grief in the context of what is, for me, the wrong religion. How to handle a painful service when the words make no emotional sense to me? I haven’t really got an answer for this. In many ways the time that feels resonant for me is what comes after the service, when there is often a sharing of food and stories; that innately human response to loss and pain. It doesn’t really matter then who believes what, we just share what we have.

March 22, 2014

Stories of emotions

Most of us tend to start from the assumption that our emotional responses are inherently right – which is a sane place to be. Those of us who cannot trust the validity of our emotions tend to be badly damaged, and make very little sense to anyone else. It’s very hard to be a functional person with a belief that your emotional responses are fundamentally invalid. However, if you’re mentally ill, you may well be feeling anxiety, paranoia and depression in ways that are not a fair reflection of reality. Simply invalidating those responses leave the sufferer even more adrift, stuck with the feelings, unable to trust them and not having some magical way of moving beyond that.

How we relate to other people’s feelings is really important in terms of how we function within communities and whether we support or undermine each other.

On a few occasions now I’ve run into people whose fundamental belief is that we all feel the same sorts of things in the same degrees and for the same reasons. Take that as a starting point and your own responses become the yardstick for what everyone else should be feeling. When this doesn’t work, it can be easy to assume there is something ‘wrong’ with the person who feels differently. Rather than face the disorientation of admitting the model is flawed, and perhaps not even able to recognise this is a model, not a truth, it can be tempting to hang on to the story and invalidate the responses of anyone who feels differently. That approach precludes any meaningful interaction with most people or their emotional experiences, and narrows our capacity for empathy.

Often our ability to empathise depends on our ability to imagine, and on how good our imaginations are. Can we take our modest, first world problems and empathise with a person who has just come out of a war zone? We may be at risk of arrogance and assumption if we think we can, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try! There is a lot of commonality in human emotion, and there are far too many people whose reality really does feature the unthinkable. Trying to imagine and empathise without becoming too attached to the stories we create that way, is a very difficult balance to strike. It’s something I struggle with, and trying to think my way into other people’s experiences is a big part of what you do as an author.

We can also practice some very unhelpful forms of double-think, where what is true for us is not assumed to be true for other people: If I feel got at clearly the other person is being mean. If you feel got at, clearly I am being challenging and perfectly reasonable. If I question your Druidry and your right to call yourself a Druid, that is my right and I’m doing you a favour. If you question mine, you are bullying and abusing me. I’ve seen this far too many times. It shuts down dialogue and makes it virtually impossible to talk about real problems. If we cling too hard to the belief that we must be right, we cannot hear when we’re getting things very wrong. If we are too readily persuaded we are entirely wrong though, we open the door to anxiety, depression and paranoia. The person who is not well cannot trust their own emotions, but it is also true that the person who is persuaded not to trust their own emotions becomes unwell.

There is an immediacy to emotion, and perhaps the most pernicious story of all is that we cannot control our responses. This idea is used to defend violence and rape at the extreme end. “I felt it and I couldn’t not do otherwise” allows pretty much anything it occurs to a person to do. No emotion is wrong – they are simply what we get. However, as we grow out of childhood, and we grow through adolescence, we should become able to control our responses to enough of a degree not to be harming other people with them.

March 21, 2014

No hierarchy of distress

Some years ago, I spent two terms on a course for abuse survivors, run by the Freedom Program. It really helped me get over what had happened and move on, and it taught me a great deal. One of the things I learned was this: Everyone there felt that other people present were far worse off than them.

Everyone had stories, and those stories were ghastly, heartbreaking and all too real. They were all far worse than anything I’d been through. But then an odd thing started happening, because other women, on hearing my stories, would say they thought it was far worse than what had happened to them. This shocked me. We all thought we’d probably deserved what had happened to us, but refused to accept that anyone else could possibly have deserved what happened to them. Through this we all began to question our feelings about our own experiences. It was a challenging process.

The idea that someone else has it worse, and we therefore shouldn’t make too much fuss may be relevant if you’ve merely broken a nail, or been slowed down by bad traffic. Perspective is useful in face of middle class, first world problems. However, that same line of thought absolutely does function to keep people in dangerous and damaging places. After all, it’s not like he cut you, other women get cut. Compared to being raped by a stranger, forced sex from someone you know really isn’t so bad. It was just a slap, not the same as being beaten up. It was only being beaten up, it’s not like you died…

Women who were imprisoned will say how much worse it must have been for women who were beaten, who think the victims of sexual assault were much worse off, but they in turn look to the women who lost their children in court battles, and feel that was much worse and the women who lost their children are so thankful that at least no one destroyed their mental health and the women whose minds were broken are busy feeling fortunate compared to the ones who were made prisoners in their own homes.

There is no hierarchy here. This is no reason for telling 90% of the victims to shut up and recognise that only one of these was really bad. The idea of a hierarchy of suffering is used to make us shut up and stop complaining. I was hit by one only this week – I should be grateful because I’m not picking plastic off rubbish dumps in a third world country. But here’s a thing: The shitty situation in my country is not a separate issue, and tackling problems here would also tackle our habit of creating this kind of waste and sending it abroad. The idea of a hierarchy of suffering breaks down the connections between problems and obscures the truth that these things are all connected. None of the things that are wrong in this world exist in a vacuum.

Think properly about the misery of the traffic jam, and you might indeed come to question commuter culture, city planning, economic pressures, modern economic models, international trade agreements and the whole structure of modern society. You can do that starting from anywhere. Don’t look for the hierarchy, look for the connections. Look for how your problem is related to someone else’s, and is part of it, feeding the same mess and creating misery. That way we can start to see what small things we might solve, that lead to actually fixing even the biggest things that are wrong. Most of those big things are gatherings of small problems, too, and it is the act of not taking the small problems seriously that prevents us from getting anywhere near the big stuff.

March 20, 2014

Benevolent Challenging

One of the consequences of suffering intermittently from depression, is that sometimes my perceptions are wonky. There are days when I can only see the bad stuff, the dangers, the trouble. I’m not especially paranoid, I don’t tend to imagine problems that do not exist. It’s about my ability to see an overall balance and to be able to find and make good bits amongst the hard stuff.

I am blessed with a number of people who make it their business to challenge me, when I get like this. They do so warmly, reminding me of alternative perspectives, of things I’ve done well or could feel good about, and that input reliably helps me get back on top of things. Sometimes it takes a while. I value that gentle challenging as an expression of care, and if you’re one of the people who knows how to poke in kindly, timely ways, thank you. It makes a huge difference.

However, there are other schools of thought around how best to challenge people. There are those who will see a person struggling and turn up with helpful suggestions like these. Stop making a fuss, you’re not as badly off as someone who has some other problem. You just need to be more positive and it will all be fine. You are being ridiculous and selfish. You are attention seeking and vamping energy from other people. Quit whining and fix it!

The trouble is, this approach assumes that the problems are trivial and fixable. People don’t always express distress over the real problem – if your parents have dementia, maybe you would feel disloyal about talking in public about the loss of dignity and the challenges. Maybe a small problem breaks you, and you get kicked by these fake do-gooders for making a fuss, because they do not know and lack the imagination to consider they may be missing some things. Sheer weight of many small problems can also break a person, and fixing a thousand issues is a large, intimidating task. If you’re hurting, you are hurting and some other person saying they’d be fine in your shoes, solves nothing.

Problem two is that if you are depressed, your self esteem is low, and your confidence is low. Someone turns up and tells you that you are stupid and useless to feel this way. For the person who was suicidal already, this confirmation that you’re a waste of space can take you closer to not being able to function. Many suicidal people do not feel able to talk about it, and fear of being called melodramatic and attention seeking certainly doesn’t help. People who can’t talk are more likely to die.

What really gets me, is that the people who are in many ways most damaging to people in pain, claim to be believers in positive thinking. They claim to value optimism and a ‘good’ approach to life. In order to maintain this comfortable bubble, it is necessary to avoid hearing anything that might burst it. It’s easy to feel positive if you are snug, secure and privileged, and hard to hear that this may be more about luck and privilege than your innate worth. If you are willing to hear when others are suffering, you might feel some moral obligation to do something about it. If you can rubbish and dismiss them, your world view is in tact, you still feel morally superior and you don’t have to do anything at all! You can even demand positive feedback for having been so good and useful in telling them how it really is.

My patience with this is at an all-time low. If you genuinely care about positivity, you respond to pain by trying to encourage, uplift, support and enable people. I’ve seen it done beautifully by people whose belief in the power of being positive is not a cover for being shitty. It’s very easy to subvert the language of positivity into something destructive, and it’s worth watching for the people who do that. Generally, anyone who feels the need to tell you they were doing you a favour and you should be grateful, was probably not doing you a favour, and is not worth taking too seriously.