Nimue Brown's Blog, page 383

August 6, 2014

Days off

People I know who take health and fitness stuff very seriously make a point of time off. Rest days, and even rest weeks when there’s no running around. Fasting days to clear out the system. It’s something I think about more than I do. The rest days are tricky because walking is my primary mode of transport and one of my main leisure activities. What else do I do all the time that it would be a good idea to take a break from?

Caffeine is an obvious candidate. I use caffeine to push through tiredness, and I use it most days. On a practical level, that reduces efficacy and can’t be doing me much good, so, a day off from caffeine now and then, or a reduced intake day, is something I try to allow myself time for. Today is a no-caffeine day.

The caffeine habit goes with a work pattern that doesn’t give me whole days off very often. Aside from the handful of things people pay me reliably to do, I have three books in progress at the moment, and unplugging from thinking about that is hard. The political side of my job requires me to pay constant attention to local and national politics – days off there are risky and infrequent. I have to know what’s going on. Sometimes I really wish I could have a day off and the respite of ignorance.

Fasting is difficult if you aren’t in a position to rest your body and mind a bit. Fasting is not a viable option if you also have to run hard, it’s just another scary pressure to add to the mix.

I’ve set today up so that I can float round the flat, and I’m intending to crash out intermittently through the day. No caffeine. There will be fruit juice and nut milk, because this is as much about changing what I do as it is about getting into the whole ‘fasting’ thing, and I’m not especially hardcore. It’s an opportunity to reflect on how I construct the ‘normal’ of my days, and whether that’s actually a good idea.

It is not my personal belief that people should work seven day weeks – it’s just that Tom and I are in a situation that makes it difficult not to. He has some hefty deadlines and spends most of his time working, and while I could take more time off (which wasn’t previously the case for me) I feel guilty about stopping when he can’t. If hard work equated to wealth, we’d be rolling in it.

It’s half nine, and I learn that I blog a lot slower without the morning coffee. My concentration is not what it could be, and today I am going to let that be ok. I’m not going to push against tiredness, I’m going to let my energy levels be low, and not do much. My theory is that this should be good for me. Thoughts on how that works in practice, to follow.

August 5, 2014

Friendly Lechery

This was another interesting lesson from Druid Camp: The value of friendly lechery. Druid Camp is a friendly place where people can take their clothes off. Amongst people who know each other, there can be a fair amount of playful, friendly flirtation and lechery. It’s important to note that this is something that can flow in any direction regardless of gender, and with scant reference to preferences sometimes. It does not exist to demean, exert control over, objectify or otherwise mistreat the participants.

In most contexts, I would be likely to find innuendos threatening because I am damaged by experience. I know that sometimes innuendo is a veiled threat of physical violence. Often it is designed to humiliate and objectify. That’s what you get when it’s perpetrated by strangers as an act of expressing power. But then, rape is all about power, it’s not about lust or desire. If what you’re dealing with is all about lust, desire, or even just liking and fondness, it’s a whole other game and not about hurting the recipient.

What sets friendly lechery apart is that for a start, it is inherently friendly. It would not continue if it made the recipient unhappy. It is supposed to elicit playful banter in return, not cowering and running away. If someone said ‘no’ or ‘this makes me uncomfortable’ it would stop, because the friendliness matters. Forcing unwanted sexual attention isn’t friendly. Making people uncomfortable isn’t friendly and if you have any care or respect for another person, making them miserable is just not an acceptable outcome.

We live in a culture that prizes sexual attractiveness. It’s also not enough in our wider culture that we are attractive to a life partner. The vibe is that we must be more widely attractive than that. We’re all regularly fed unattainable, photoshopped images of desirability. At the same time, our society is entirely crap about giving us positive messages about how we look and seem. That’s not going to get us to buy products, after all! We’re having our sexuality constructed for us by people who want to undermine our confidence in ourselves, while making us feel we must be universally appealing, in order to make us buy stuff.

One of the gifts of friendly lechery is that it allows us to affirm attractiveness to each other without consuming anything. With flirtation and innuendo, we affirm each other’s acceptability, and when that’s done well, it is a cheering experience. We should not automatically feel degraded by another person’s appreciation, we also shouldn’t need to feel like everyone fancies us, but we’re all under a lot of pressure over this one.

There’s an interesting parallel with Steampunk culture here. In Steampunk, clothes dominate, and it is not just normal, but expected that you will approach other people to compliment them on hats, clothes, accessories and style. In this context it is fine for anyone to pay a compliment to anyone else, because it is understood as part of how the culture works. Other places, that same behaviour might be interpreted as creepy or threatening. A big part of what makes the difference here, and in Druid circles, is the understanding that respect can be assumed. When you know you are respected, any comment about appearance and attractiveness is heard differently. It’s not a prelude to assault.

In most situations with people we do not know well, respect is not a given. Physical safety is not a given. Acceptance of your sexuality is not a given. Making jokes at the expense of others is normal.

If the people around us are not objects, then the lechery is personal. It exists in a context, as part of an exchange, and if that’s not ok, then the flirting, the play and suggestion stops. To expose attraction is, in this context, to be vulnerable. Only when we objectify people can we express unsolicited lust without feeling vulnerable. Only if we are also laughing at the recipient can we feel relaxed about desiring someone who might say no. And of course if we keep laughing, we might not bother to hear the ‘no’ anyway. In objectifying another person in order to be lecherous at them, we might feel sexually powerful, and as though we have turned attention away from the issue of our own desirability. Friendly lechery, by contrast, allows us all to be a bit more real, human and gentle with each other.

August 4, 2014

The war to end all wars

One hundred years ago today, Britain declared war on Germany, in what was soon labelled as the war to end all wars. The scale of death so shocked people of the time that they all imagined no one would ever do anything like it again. We had established, beyond any shadow of a doubt, that war is a miserable and futile thing, with unspeakable costs, and that you can spend years killing people in their thousands and make no meaningful political changes.

If we had any sense as a species, that would have been it, and we’d never have had a war since. A hundred years on, and we’re still in the habit of killing each other in horrible ways that ultimately change very little outside of the personal tragedies. Why? Because there is always someone who thinks violence will get them what they want. Fear of the aggressor means that nations who would like to view themselves as non-aggressive have to keep weapons and armies to protect themselves, right through to protecting themselves with pre-emptive strikes. There are people in the weapons trade who make a fortune out of war, and if you’re a politician with an eye to history book posterity, war remains tempting. This is in turn because we so often write our histories as the history of warfare and commanders.

If words like ‘glorious’ and ‘heroic’ are associated with killing people, the whole thing is a lot more attractive. A glance at the WW1 poets will show you a bunch of young men who had been told how noble and good it was to lay down your life for your country, not how awful it was watching a friend slowly choke to death on gas. What would our attitude to war be like if we taught more social history? What if we taught the history of science more, or the history of democracy? There are some very interesting and informative histories out there and if you study history until the age of 14, you’ll barely know they exist. You will know a fair bit about the two world wars. You’ll probably know Norman conquest and Saxon raiders, a few kings and queens, a few other big, important fights. If you’re American, you’d expect to know all about the war of independence and the civil war. Our histories are so often the histories of violence, as though only this past exists and is available to talk about.

It would be lovely if all the people in power figured out how to never start another war. I won’t hold my breath. We’d have to give up on greed, on bids to control resources, religious hatred, cultural imperialism, and fear of each other. We’re a long ways from doing those things. Many of us live in societies that make token gestures at being democratic. In theory, the will of the people means something. The culture a leader thinks they come from certainly has an influence. Financial pressure talks.

We are not going to get world peace by waiting around for the power hungry, greed driven idiots who grab power to play nicely. It’s going to have to come from a grass roots, from a culture that does not love and romanticise violence through its films, does not hero-worship killers and tell proud stories of the slaughter in its history. A culture that sees violence as failure will be a lot less inclined to get into wars. A culture that does not see leadership potential in swaggering bully boys who want to play at soldiers (either gender, with all due reference to Margaret Thatcher). Right wing politics is riddled with the language of macho violence even when it’s not planning to kill anyone directly. It’s all wars on things, fights, tough choices, it’s the language of conquest and victory. What we need is culture of co-operation that has good relationships with other cultures rather than living in fear of them.

We’re a very long way from there, one hundred years after the war to end all wars didn’t. That doesn’t make it impossible, or any less worth trying for. Until we change the culture of leadership, it isn’t going to come from those who lead.

August 3, 2014

Managing nature

Should we attempt to ‘manage’ nature or is it best to let the natural world take care of itself, and to avoid human intervention as far as possible? It’s an interesting question, and one I think it is worth poking around in a bit.

Firstly, for this to make sense, we have to assume that nature is separate from humanity and that anything humans do must be at odds with nature, rather than part of it. Moorland and meadows in the UK exist as a consequence of humans farming animals over thousands of years. We’ve been doing this long enough that many landscapes in Europe are shaped by our presence, and many species have evolved a little bit to utilise what we do. There are woodland flowers that just never grow if no one coppices the woods to let in the light.

Secondly, nature is slow to adapt, and very happy to adapt by letting things die out. We have unbalanced many natural systems, often by taking out top level predators. I recall a tale of a place that, on returning its wolves found the mountainsides became glorious with flowers because they were no longer being cropped. Often we don’t know the knock on effects of our unbalancing are, and in re-balancing, we learn valuable lessons.

Thirdly, in leaving nature to sort itself out, we may let ourselves off the hook. It is worth remembering that the desire to manage otter populations (born of a desire to hunt them) alerted us to the dire state of our water systems and the need for a human clean-up program. When we’re trying to manage nature, we are, I suggest, more likely to be aware of and taking responsibility for our own impact.

Fourthly, managing nature often means trying to change spaces – sometimes that means attempting to undo what humans have done to them, sometimes it means creating habitat from scratch to serve a need. Planting trees, clearing silted ponds, re-establishing wetland, removing invasive species like rhododendron and Japanese knotweed, putting up nesting boxes, creating otter holts – these are all attempts at managing nature. They replace habitat we have destroyed, and they give vulnerable species a fighting chance.

Humans interact with the rest of the world in all things. Mostly we are careless about the needs of other life forms, and we cause widespread habitat destruction and loss of species. In many places, we have been a presence for so long that we are part of the landscape and there is not letting it revert to some imagined ‘natural’ state without losing diversity that way. A stand of trees may look natural, but if what you had before was a grassland maintained by grazing, and full of rare orchids, then the ‘natural’ reverting to a stand of trees means losing the orchids, and the insects who lived in the grass.

We have created a relationship with the rest of nature. If we view ourselves as custodians, duty bound to take care of the land, I think we’ll do a better job of not being destructive. The risk in imagining nature will take care of itself if we leave it alone, is that we fail to recognise the scale on which we are not leaving it alone in the first place. There are fairly pristine landscapes out there, it would be fantastic if we could leave them alone, but our pollution gets everywhere, so not interfering even in places we never see is going to require some effort.

August 2, 2014

Naked Pagans

After last year’s Druid Camp, I wrote about my experiences of Naked Men, so it seemed like a good time to revisit the subject. I’ve been to Druid Camp, there was nudity. Unlike last year, I went in knowing I could cope perfectly well with the exposed bodies, and that nothing bad would happen. As predicted, it was all perfectly fine, comfortable and easy.

However, as I was spending less time fretting, I managed to do more observing and thinking (not in a pervy way!). What occurred to me, was this:

In a space where nudity is normal, nothing can be inferred from the presence or absence of clothes, nor from the degree of clothedness. In normalising nudity, what you do is wipe out any scope for people thinking that bare skin equates to sexual consent. I think there’s also an effect of undermining the erotic power of nudity, too. If lots of people are casually naked, you become much less affected by it, much more relaxed about it. The idea of being inflamed to uncontrolled lust by the sight of a breast gets preposterous.

The culture of covering up has fetishised nudity. This in turn gives us the ludicrous idea that the presence or absence of clothing or certain kinds of clothing can be reasonably inferred to mean consent. In the culture of Druid Camp, it’s wholly evident that naked people are not asking for it. If someone is asking for it, you tend to know because they make that obvious, by asking for it with words. Naked people may in fact lead to a culture where courtship, wooing and friendly seduction are far more appropriate ways forward. The impersonal nudity of Camp means that if you’re interested, you need to ask. You need to pay attention to what people say and do, not how they look. Oddly, naked people in the right context can be harder to objectify.

These are lessons we could do with learning in the wider culture, regardless of whether people have their kit off. The trouble with Britain is that it is frequently wet and cold – I write this on a day when no sane person would want to expose skin to the unkind elements. How we feel collectively about nudity is not really informed by how many naked Pagans we get to see… but sometimes it helps.

August 1, 2014

The value of a person

Last week at Druid Camp, Green MEP Molly Scott Cato came and gave a talk about the nature of money. Molly isn’t a Druid, it should be noted, but is open to talking to any group of people who want to listen. Druid Camp is about finding ways to engage with the world as a Druid as well as retreating into a shared community space.

In Molly’s talk, she reflected on how people equate pay with value, where more pay seems to indicate that a person has more innate worth to those paying them. It’s a seductive way of thinking that traps us into putting a price tag on everything, and then not valuing those people and naturally occurring things that do not merit a high price.

We should pay fairly for time and skills, but the pressure in a capitalist system is to extract as much profit as possible, often meaning we will pay the less powerful less than they are worth to us. Unions were a way of countering this, but they have been restricted repeatedly by politicians. When we make hierarchies of worth, assumptions creep into the mix. Traditionally feminine areas are often considered less valuable than traditional masculine employment, for example. Hard physical labour is not valued as highly as desk jobs (unless there’s also a gender issue). Producing the product is deemed less important than managing the people who produce the product. And on the strange flip side of all of this, get high enough up the ladder and you can lose money for your company and still expect to be paid a vast salary and a hefty bonus. How we deploy wages could certainly stand some thought.

The value of a person is not their earning ability, and we should not be valuing each other in terms of cash flow. It’s horribly reductive, undermines self esteem and leaves us all vulnerable. What value do you have if you fall sick, retire, or your company folds, if you take time out to raise children or care for a sick relative, to campaign, study or the like? We are not our paychecks.

This only holds up though when you postulate that people are earning enough to maintain a decent standard of living. If you do not earn a living wage, and must work two jobs just to survive, or sell your possessions, or do without many otherwise normal things, you will feel keenly that you are not worth much as a person. It will be there every time you desperately need to say ‘no’ but can’t afford to. Loss of economic power is also loss of self, when it means you have to work any hours offered at no notice, or when it means you resort to selling your body, through pornography or prostitution. The person who cannot afford to eat properly doesn’t get to make so many ethical choices about what their employer asks of them. Undervalue a person economically, and you take away their rights to function as a person in your society.

Only when everyone has enough to maintain a decent standard of living, can we sit back and feel confident that the size of a paycheck is not the value we place on a person.

July 31, 2014

Druid camp faerie tales

Thursday at Druid Camp, and there was to be a masked ball in the evening. I had nothing to wear – I don’t own many dresses and as nothing in my wardrobe would do for a glamorous Druid ball in hot conditions, I had brought a few things in the hopes I could cobble them together, apply face-paint and get away with it. However, Thursday turned out to be busy, I didn’t stop until gone 8, by which time everyone else was ready while I was hot, tired and painfully sore.

This may be starting to sound a bit like a familiar story shape. I was definitely not going to the ball, because by this point my lower back had locked up and was painful enough to make me cry. Dancing would not be an option. Everyone else set off, aside from Tom, but Ferdiad returned, taking on the ‘faerie godmother’ role (which I think should be generally understood more as a job description than an identity). It took some time and energy to get me out of the worst of the pain and return me to a state I could bear.

I did not go to the ball.

This is where it gets really interesting, because on Friday the suggestion was mooted that it might be worth getting me in the sauna, to alleviate pain and tension. I can’t cope with being naked around people, and while I’m better with other people’s nudity than I was, it’s still tough. At Rainbow Camps there are often naked people. A quiet window was found where I could have sauna time without anyone else, and various people accompanied me to help me feel secure as I did this more communally again in following days. However, on that Friday we discovered that in terms of pain and stiffness, a sauna is pretty much an instant magical cure. As I don’t normally believe in instant magical cures, this came as a surprise. It doesn’t fix me forever, but it quickly returns me to a viable state.

On Friday night, I was sufficiently pain-free to be able to dance a bit while the band was on. Not much, not too energetically and not for too long, but some wafting about to music was viable. This cheered me greatly. The not being able to dance aspect of not going to the ball had been gutting – I love to dance, but these days it’s not always so feasible. If my body is stiff and awkward, liveliness and grace are not an option.

On Saturday at the market, there was a dress. Black bodice, dark green skirt. A glorious, outrageous sort of dress compared to the kinds of things I more normally wear. I tried it on, and it was an uncannily good fit. I tend to self identify as scruffy urchin, but this dress managed to both look rather fancy, and look like me – I did not appear to be trying to be anything or anyone I am not. I wore it barefoot and with no makeup, and that was fine. On Saturday, I went to the eistedfodd in said dress, and people said nice things about it. I spent a lot of the evening at the back of the marquee, in the fabulous frock, listening to the music whilst sewing up stretches of scarf for Wool Against Weapons. I also managed a bit of dancing.

Faerie tale outcomes tend to fall together neatly so as to make a good narrative. Life can take a lot longer to come up with good outcomes, but just sometimes, when we look out for each other and enable good things to happen, there are moments of magic. Thank you everyone who made that possible, it meant a great deal to me.

July 30, 2014

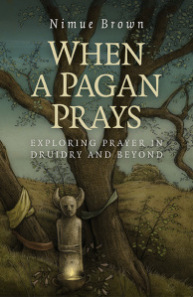

Book Review – When a Pagan Prays, by Nimue Brown

Today I would like to share with you Joanna van der Hoeven’s reflections on my latest book: When a Pagan Prays.

Originally posted on Down the Forest Path:

Originally posted on Down the Forest Path:

Cover art copyright Tom Brown

Prayer – formulating into coherent words or actions in the manner of prayer can make such a huge difference to our otherwise scattered thoughts, whether we speak them aloud to deity, spirits, ancestors or whatever we feel we would like to connect with that might be listening. This solidifying of thoughts, queries, petitions or thanksgiving is what makes prayer so beneficial. No longer ethereal or mysterious floaty thoughts, as humans who use language and gestures we define ourselves through prayer, if we so choose. The subject of the ethics of prayer brings to the fore that which humanity so often fails at – looking outside ourselves at the bigger picture. When graced by human consciousness, we should all be looking to live with compassion with all beings. Sadly the ethics of prayer can be abused by the simple fallibility of humanity.

Brown forthrightly explores prayer…

View original 138 more words

July 29, 2014

Tales of a cat

I had thought today I would be writing an elegy for a much loved cat. It is not quite as I had anticipated.

I had thought today I would be writing an elegy for a much loved cat. It is not quite as I had anticipated.

Mr Cat, also known sometimes as Mason Rumblepurr and a whole host of other titles, gave up on being a corporeal cat last week, having had several strokes. He was nearly 17 and had lived a good life. He came to me aged ten, from a happy home because his people were emigrating. He travelled with me, to cottage, narrowboat and finally this flat. He loved boat life, and was happiest there with the woodstove and an abundance of opportunities for sunbathing, and beating up dogs. He was a glorious and eccentric cat, partial to chilli, and with a veritable fetish for balls of wool. He was excellent company; a friendly chap who regularly won hearts.

And at this point, I was expecting to say how much we are going to miss him.

To miss something, you need to feel its absence. He was such a strong presence, and he remains that. What we have instead is the strange journey of coming to terms with a physical absence, along with a keen sense that we remain a family of four, one of whom is just a bit less tangible than previously.

I have no coherent stories about what happens when we die. I have a suspicion that it isn’t a single event, just as being born means very different things for different people. Perhaps death is as individual as life. I hope so.

July 28, 2014

Is modesty a virtue?

In many religions, modesty in dress and behaviour is considered to be a virtue. This is especially true in the sense of sexual modesty, and is often applied to both genders. Mainstream culture by contrast uses sex to sell just about everything, and favours presenting the body as object – especially the female body. Display is actively encouraged in both genders, but women are also routinely shamed for it. As Paganism tends to be a sex-positive religion, how do we begin to make sense of all this?

To be clear about my own biases, I tend to cover up. I feel more secure covered up and am averse to receiving attention that has any kind of sexual aspect to it from the vast majority of people. I cover up because I favour practical clothes and it suits me to avoid both cold and sunburn by this means. I feel less self conscious when my body is not on display. This has not always been true of me and there have been times in my life when I’ve felt free, willing and able to make my body more visually available. I am not offended by people choosing to cover up, and I am not offended by people choosing to dress provocatively.

Modesty works as a virtue when covering up enables you to hold your sexuality and your body in some very specific ways, and in so doing uphold a religious position. Where it doesn’t work is if it is forced. A person who is made to do something or who does it out of fear is not upholding a virtue. There is nothing particularly virtuous about my covering up – it is protective and about personal comfort. If I wanted to make a powerful dedication, it would probably be more appropriate to bare my breasts like a Minoan priestess – precisely because I would find that so unspeakably hard to do.

With all due reference to that iconic Minoan priestess issue, and to the images of bared breasts in Egyptian mythology, and all the bodily representations scattered through ancient Pagan cultures… there’s clearly every scope for Pagan virtue in the baring of the body. It is an honouring of nature to be unashamed of your naked self. It can be used in ritual for all kinds of reasons. But again, if we do that because we feel we ‘should’, under pressure from someone else, or otherwise under duress, it is no virtue at all. If we do it with no respect for our own bodies or anyone else’s there is no virtue.

Virtues are seldom fixed and definite things in Paganism, and there can be many ways of approaching any of them. Without knowing the reasons a person does something, it is very hard to judge if they are being virtuous, or acting for their own convenience, or are afraid. Judging each other tends to be a total waste of time and energy. Is there any virtue at all in doing what comes most naturally to us, or is that the most virtuous thing a Pagan can do?