Nimue Brown's Blog, page 353

June 7, 2015

Sins of the fathers

I’m fascinated by the ways in which stories, behavioural patterns, beliefs and ways of being are passed down from one generation to the next. What we inherit can be totally invisible to us, and it can take years to spot that we’re playing out some other family dynamic in our own relationships, or perpetuating a family myth. Some people never know what it is that they are doing, or why. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to unpick the myths of my own family, and while I can now see some of them, I have no way of explaining them, I do not know where or when they started and can only guess.

I’m fascinated by the ways in which stories, behavioural patterns, beliefs and ways of being are passed down from one generation to the next. What we inherit can be totally invisible to us, and it can take years to spot that we’re playing out some other family dynamic in our own relationships, or perpetuating a family myth. Some people never know what it is that they are doing, or why. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to unpick the myths of my own family, and while I can now see some of them, I have no way of explaining them, I do not know where or when they started and can only guess.

When we know what the history is and who has made the story, we have a much better shot at not repeating it. This was all very much on my mind when writing Druidry and the Ancestors, but it’s a theme I’ve taken up in my fiction work as well. The current instalment of Hopeless Maine, book 3: Sinners, started life with the longer title ‘Sins of the Fathers’. Although sins of at least one mother are also very much part of the mix.

It’s interesting how often parents do not turn up in novels and fairy stories. The dead parents are such a routine feature. The absent or unknown parents crop up a lot. The young adventurer who is obliged to set out into the world and seek their fortune, somewhere else. They go somewhere they are not known, and where they can meet their destiny free from the implications of their birth. By this means, the sons of humble woodcutters may become princes and so forth. Anyone standing in for a parent, as a mentor, guide and guardian can expect the Star Wars treatment – to be suddenly cut down so that the hero must stand alone and face their destiny.

Real life does not deliver this for most of us. We will live our lives connected to our family roots, and many of us will deal with our most immediate ancestors in ongoing ways. The stories handed down to us about who we are and how we should act stay with us too. It’s one of the things I like about Hopeless Maine* as a setting – it’s really claustrophobic. Mostly the only way to leave the island is to die, and that’s not wholly reliable. Our young heroes, Sal and Owen, are living in a tiny world shaped in part by their parent’s actions, and obliged to deal with who they are, and where they come from. Granted, their troubles are not exactly akin to anyone else’s – Sal’s mother lives under the graveyard and only goes out at night. Owen’s father may be suffering from madness, or grief, or hatred, or possession, or love betrayed, or all of the above, and has means to express that, which aren’t available to most of us.

We live with the sins of our ancestors. We live after slavery, after the enclosures act that robbed the common people of Britain of their land. We live after highland clearances and colonialism, after Auschwitz. We live with a modern Israel whose conflicts have been thousands of years in the making. We live with the absence of the dodo, the carrier pigeon and the aurochs, with the poisonous legacies of industrial revolution and nuclear power. The sins of our ancestors are many. The choices they have made in fear, in greed and in ignorance shape the world as we have it now. There is nowhere else for us to go, no bold new place we can strike out to where they won’t know about our past or judge us for where we came from. We have to stay and deal with the consequences of things done in madness, in grief, in hatred and in fear. Either we change those stories, or we pass them on and see if our children are any more capable of being heroes than we were.

*Hopeless Maine is a webcomic, you can read it for free at http://www.hopelssmaine.com, the image accompanying this blog is the cover art for book 3.

June 6, 2015

Into the landscape

The combination of car use and ever more urban living means that most people have no sense of their place within the landscape they inhabit. Cities are as much in landscapes as anything else, but they tend not to invite people to think of themselves in relation to the soil. Car use takes our encounter with the land up to a pace where it is meaningless. There’s just too much that cannot be experienced and absorbed when you’re moving at speed, and the insulating effect of the small box doesn’t help much either. On this front, public transport is equally useless; also too fast and too distancing.

If you have no relationship with the land, then you get the disorientating effect of not really knowing where you are. This is me on the London Underground, unable to connect the map to anything happening in the street, and when on the street, disorientated by the sheer number of people, cars, streets and so forth. Put me in an unfamiliar forest and I have some tools to make sense and find my way around. Put me in an unfamiliar town and I can apply those same tools to often workable effect, but the bigger and busier the city, the less able I am to orientate myself within it, and part of that is due to the sheer amount of information coming at me every second.

To know an area on foot, starting from your own front door is to know it with your body. Any other body-paced mode of transport will have a similar effect, and even knowing a small area is of considerable value. This is a different kind of knowing, informed by the shape of the land, and the key features within it, a knowing that builds an inner map, and an understanding of how one focal point connects to another. Walking between the places where you do things places your life within a mapped landscape, and provides a kind of sense that is felt rather than intellectual. It is not just the space that makes more sense this way, but also the life, and that which is done in each place.

There is nothing stopping any of us from returning to the land. If the land is under tarmac, it is still the land. If you are not so mobile then just being still outside when and where you can helps you return to the land. The modern life we are so relentlessly sold, is a fast paced, rootless flurry; urgent, frantic and disconnected. To move slowly is to change that. To be on the ground, in whatever way you can be, is to be grounded. To move at a human pace is to become real to yourself and to bring coherence to your life.

June 5, 2015

In the austerity household

Part of the austerity narrative is the idea that the country is like a household and if you’d maxed out your credit cards you’d have to cut back on spending. Leaving aside the fact that country level economics do not have any resemblance to a household because the rules are different, let’s see how the austerity house might look.

Grandparent 1 owns the austerity house and grandparent 2 makes all the decisions about what happens in it. Parent one goes out to work and earns all the money to run the household. Parent 2 does all the cooking, cleaning, childcare, teaching, nursing, puts out fires… you get the idea. There are an unspecified number of children, and also a hamster. Now they’ve run up a big debt. How does austerity play out?

Well, that foster child they took on is 16 now, so they throw him out and give him no further financial support. That’s going to save some money. Rather than take all of parent 2’s work for free, parent 2 is told to go out and get a ‘proper’ job, while the grandparents pay privately for some of the services they want – nurses and a gardener although they expect parent 2 to keep teaching and putting out fires and suggest parent 2 could cut back on sleep.

Because other households are doing the same things, parent 1 is spending ever longer hours working for the same money, while the grandparents demand that parent 1 uses more of the income to pay off the debt. Parent 1 takes a second job, but that isn’t enough. Parent 1’s car is sold off for less than it costs to pay off the finance on it. The grandparents claim they are raising funds by selling off other household items for less than they are worth, but rather than spend this on the food budget for the household, they buy themselves takeaways, leaving the parents struggling with the expense and inconvenience caused by having key assets stripped away.

The youngest child fails to get good grades, and is denied food for 2 weeks as a consequence. The hamster disappears, presumed eaten. Parent 2 takes up prostitution in a desperate attempt to pay for the finance on the car that is no longer there and the rising cost of now necessary bus fares.

Annoyed by the neighbour’s cat crapping in the garden, the grandparents get on ebay and buy some small scale nuclear weapons from China, wiping out the household’s food budget for the next ten years. One of the children develops rickets, and the grandparents borrow money to buy themselves an enormous train set.

Sounds ludicrous, doesn’t it? And yet our government is seriously considering putting vast amounts of public money into a nuclear submarine even the army doesn’t want, and a high speed rail project that merely shaves a bit of time off the London to Birmingham journey, while at the same time cutting funding for the poor and vulnerable. If a parent is hit by benefit sanctions for 2 weeks and can’t afford food, of course there are children not eating properly as well. And now they’re planning to sell off a nationally owned bank at an incredible loss.

There is no justice, no economic sense and no humanity in the current political program. What it delivers is misery. If the household analogy were true, we’d be handling this differently. A household that has maxed out its credit cards doesn’t save money by starving its children, it cuts luxuries first. Holidays, takeaways, new clothes, train sets. You pay your core bills and feed everyone, and if you have to sell assets, you aim to make a profit on them, not put yourself further in debt. If this country is like living in a household, then we have the economics that go with one family member being a secret crack addict.

June 4, 2015

Fast Food Politics

Back when I started writing the novel version of Fast Food at the Centre of the World, food banks were not on most people’s minds. We were well underway with the current obesity epidemic, but at the same time, it wasn’t at the level it is now. Monsanto were busily trying to take control of the world’s seeds, but again, things have escalated over recent years. The increasing threat of climate change, and the shocking degree of both hunger and food waste in the world make food an intensely political subject.

Back when I started writing the novel version of Fast Food at the Centre of the World, food banks were not on most people’s minds. We were well underway with the current obesity epidemic, but at the same time, it wasn’t at the level it is now. Monsanto were busily trying to take control of the world’s seeds, but again, things have escalated over recent years. The increasing threat of climate change, and the shocking degree of both hunger and food waste in the world make food an intensely political subject.

Food is also about our connection with nature. Young people today are growing up indoors, factory farmed by an increasingly pressured educational system and then distracted with small electrical boxes. They don’t get out much, they don’t play, they eat edible food-like substances and too many of them bloat. How many modern children will eat berries from a hedge or pick apples? How many would have a clue as to what they could safely forage? How many would want to?

Increasingly, we are imagining and developing food as something separate from nature; a manufacturing process that delivers it shrink wrapped, by lorry, to a supermarket shelf near you. How many children will get to lift a potato from the soil for themselves? How many will see a potato with mud on, and have to wash it? Vegetables come pressure washed, partially skinned and eager to decay.

It doesn’t get much more basic than food. In terms of basic survival, food is key. In terms of health, the state of your immune system, and your long term prospects, food plays an important part. And yet, we seem happy to accept whatever comes in the packets, and have done for years. The additives, some of which it turned out made children hyperactive. The sweeteners in soft drinks that will dry your mouth out and leave you feeling more thirsty. The trans fats, the corn syrups, the rising use of palm oil and its catastrophic implications for rain forests. The welfare of animals raised in utter misery to feed us. Animals sustained by antibiotics that are, through their overuse, reducing the usefulness of this vital medicine for treating human ailments.

Food is a battleground in which the profits of big business do war upon your health and wellbeing. Food is a battleground on every piece of land where indigenous species are wiped out to make way for farming. Agriculture is not blameless in this process. Just because you aren’t eating animals doesn’t mean your diet isn’t implicated in killing them (I say this as a vegetarian). Nuts, soya, palm oil, exotic fruits… it is not a comfortable thing to consider what a cashew costs in terms of lost habitat. Food is a battleground between us and every other species, and yet we waste so much of what is produced, we kill and destroy for no good reason, all too often. Viewed from a distance, it might look a lot like an inter-species form of genocide in which we go forth to wipe out everything that isn’t us and doesn’t overtly serve us.

Food is nature. Food is politics. It is health. Food is our relationship with the world, and with each other. Hunger and excess should be matters of shame and alarm. Some of our children are rotunned with bad food and limited lives. Some of our children are dying of hunger.

We really need to start caring about this. I know, when I write here that I am largely preaching to the converted, that you’re reading because you share my concerns and beliefs about a fair few things. The challenge, for me, is in reaching out to people who are wilfully oblivious, convinced it’s not their problem, or that there is no problem. Fast Food at the Centre of the World is a bit of a stealth project. It’s an audio serialisation of the novel, free to listen to, and raises food issues, but it does so with magic, zombies, plenty of comedy, a slightly deranged magician and a fast food restaurant like no other. If I can just get one or two people thinking about food in different ways, that would be awesome.

June 3, 2015

The spiritual materialist

I’m a very materialistic person, in that I love and value objects. There are many items in my home that are precious to me and that I would be grieved to part with. Musical instruments. A bookcase that belonged to my great grandparents. Gifts from friends, handmade items, objects made with love and skill. Some of my grandmother’s artwork. The artwork of people I admire. Books. So many books. I’ve collected the objects that share my space with care and attention and some of them have been with me a very long time. They have stories, which weave their existence into mine. They have utility and beauty. I am attached to them.

Materialism gets a really bad name. It is used to imply greed and consumption, and fixation on the wrong things. Many (but not all) religions divide the physical world from the spiritual, and to be involved with things material is to be less spiritual in such paradigms. To own little and feel nothing for it may be a spiritual goal for some, but it doesn’t really work for me, because I become fond of things.

To my eye, consumerism, and the kind of materialism that sees objects as the means to status works in very different ways. The object is not valued for itself, but for what others might think of it, for the status or power it gives. If a better object comes along, the old one will be discarded. There is no affection for the object in a consumerist mentality. Equally, greed is about stacking up as much as you can that has a value. It’s not about having things you can use or that are beautiful, it’s about having things for the sake of having them and in the hopes of having a bigger pile than someone else. Things are bought because buying is soothing, display empowering, ownership appealing. There is no other connection between the person and the object.

Where there is a relationship between person and object, created by history and story, gifting, use, beauty and fondness, the object is not disposable. I would not replace my great grandparent’s bookcase with the most expensive bookcase in the world even if someone offered it me for free. I like the things around me and am not on the lookout for ‘upgrades’.

Peltless, squishy things that we are, we depend on objects to keep us warm, to act as tools, and we’ve got very good at making things that help us do more than just survive. I sit at a chair by a table, and I am glad of these things. Glad of the window, the bed and all the other useful things in my space. There’s not much here for anyone else to covet, or be awed by, or that could cause someone to think I had power, which is fine because I don’t. There is no desire to impress, just a small space I find comfortable and pleasing.

I find it curious that religions can teach poverty as a virtue and argue against any affection for the material, whilst accumulating great wealth for temples and turning a blind eye to the excesses of the rich and powerful. It is my suspicion that poverty as a virtue has bugger all to do with spirituality and everything to do with keeping the poor meek and compliant. The absence of care and affection for what is around you is a far greater spiritual shortcoming than liking your own small nest. The throwaway, status obsessed careless attitudes that go with the desire to display wealth and own precious things, the mindset that takes beautiful art and locks it in vaults as an investment, seems a lot more suspect to me than any small scale homely materialism ever could.

Poverty is not piety in any faith, and affluence is not virtue. Care and kindness, generosity and warmth are things you can do with whatever you have.

June 2, 2015

Unpicking the double standards

Part of the work I’ve been doing in recent weeks has been to try and unpick the logic holding together my personal reality. Without understanding the mechanics, it is difficult to make conscious and deliberate changes (but not, it should be noted, impossible.) There is history here, and lots of it, and I could tell stories of how I got to be where I am – but they are long and dull, and the stories underpinning your reality will be very different anyway.

I don’t know if it’s a bottom line, but the issue of double standards is a large and serious part of why I see things as I do. Being trained to accept and uphold a double standard underpins a reality of twisted logic and inherent unfairness. Perhaps it is because of the double standard that I do not protect my boundaries well and have on a number of occasions ended up far more involved with unreasonable people than was good for me. They are allowed to get angry about things, I am not. They are right, and I am wrong (always) they are good and I am unreasonable, they are perfectly acceptable as they are, I must work very hard and make lots of changes. And so on. Endlessly. It’s impossible to be happy if I don’t spot this early and step away from it.

My acceptance of the double standard has been absolute. In my toughest patches, ingesting the double standard further has left me feeling sub-human, made of straw, not a real person. Of course they would react this way. Of course they would treat me like this. And so I don’t stand up for myself, protect my boundaries or ask for what I need all too often, and I perpetuate the double standard still further and accept it as who I am. It becomes ok to hurt me, to ignore me, blow hot and cold, get cross with me, mess me about in any number of ways, make impossible demands.

There’s very little I can do about other people’s attitudes to me, current or historical. What I can do, and have done, is to question my own beliefs and choices. It hasn’t been easy, letting go of the idea that there is something about me which makes any kind of unkindness or lack of care make perfect sense. I’ve kept this story because it has allowed me to think well of people who I otherwise cannot think well of. It allows me to function in situations where otherwise I might quit and run away. I have come to the conclusion that this is not a good thing.

Habits and beliefs of a lifetime do not fall away overnight. To change this I am going to have to pay a lot of attention to my own emotional responses, to spot what I genuinely feel before I slip into suppression and co-operation mode. I have to watch my own thinking, alert to signs that I am letting someone else get away with something that would be totally unacceptable if I did it. I have to check my actions and make sure I’m not doing things that keep me in these loops. None of this will resolve quickly, but habits of thought can be changed.

I need to draw up some new lines about what is acceptable and what isn’t. I need to work out what is intolerable to me, draw a line, and hold it. Without these things, proper boundaries and a sense of self are just not available, and to go forward, I need to relate to myself as being as much a person as anyone else.

June 1, 2015

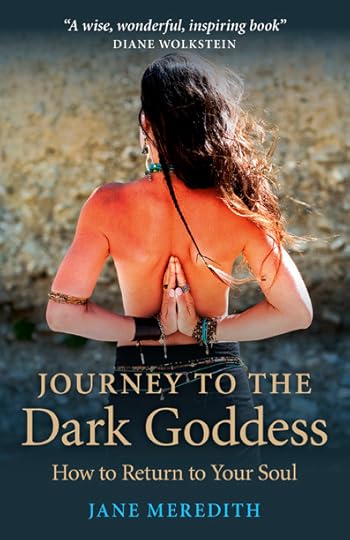

Handbook for a Dark Journey

Jane Meredith’s Journey to a Dark Goddess landed in a really timely way for me. It’s a book about journeys to the underworld – journeys into depression, despair, crisis and breakdown. Usually we go because we have no choice, life falls apart, mental health collapses and we walk a dark road from which we might, or might not return. It is a journey that kills some people. One of the things this book offers is a map of the way down (not a map that will give everyone their exact journey, but a sense of the terrain at least) and some pointers for finding a way out.

Jane Meredith’s Journey to a Dark Goddess landed in a really timely way for me. It’s a book about journeys to the underworld – journeys into depression, despair, crisis and breakdown. Usually we go because we have no choice, life falls apart, mental health collapses and we walk a dark road from which we might, or might not return. It is a journey that kills some people. One of the things this book offers is a map of the way down (not a map that will give everyone their exact journey, but a sense of the terrain at least) and some pointers for finding a way out.

I’d been stuck for a while. A couple of months ago I made the decision to work with my distress rather than trying to suppress it. I made a lot of headway and came to understand a lot of things, and then it all slowed and I settled in a low, dark place with no idea of how to move. I didn’t want to push myself out and back up to normal life and regular functioning, that didn’t feel right. It’s how I normally handle depression, pushing to return to functionality and utility as soon as I can, and I was trying to shift my patterns.

One of the things this book did for me was make me really see how deeply the push to be normal is implicated in the process of falling down into the dark places. It’s not about me. It’s all about being useful and convenient for everyone else. There is no space to change and heal unless I make and hold a space that is for me. I have so much invested in being useful, it’s been a key part of my sense of self. Can I hold time for not being useful, even for being inconvenient so that I can do what needs doing for me? For the first time, the answer might be ‘yes’. Can I go further and change my sense of self so that utility and convenience to others are not so dominant? Perhaps I can.

I’ve spent years peeling away the layers of my dysfunction, examining what goes on inside my head to try and make sense of why I get ill and depressed. Obviously if I didn’t get ill and depressed, I could be much more useful. I would be more convenient, and these have been far greater motivators to changing than any desire to heal. And so I unpick, and pull back layers to see what is underneath them, trace back threads of thought and feeling to see where they come from. I had figured out a lot, by the time I got stuck, and I had got stuck because I could see no way of doing differently with what I have. Now I see that I must change what I have, and there are things I can stop going along with.

All the things that are not convenient – my moods and emotions, my vulnerabilities and dreaming – are things that I need. If I spend most of my life ignoring, denying and suppressing vast swathes of myself, little wonder that I crack up fairly regularly. I can’t be a china doll automata, always smiling and doing as it is told and also be something alive and human.

I have to be allowed to feel and want, to say no, to not want, to dislike, to get cross. I have to be able to like and not like based entirely on my own preferences. I can negotiate and co-operate from a position of being honest about my own needs and feelings, I feel certain. Don’t and won’t and don’t want to and am not interested and no, are words that I need to embrace. All the things that I consider fair and reasonable when other people do them have to be available to me as well – there is a huge double standard underpinning all of this, and I do not have to keep going along with it. I have the power to change things.

Jane Meredith’s book has been a huge help in making sense of where I am, and showing me what I need to do to change things for myself.

May 31, 2015

At the Temple of Nodens

The ancestors did not speak to me, although I walked barefoot into their temple.

At the triple shrine, the Gods did not speak to me. I wondered who the other two might have been.

I sat in the grass and watched determined ants carry their eggs from the old place to the new place, wherever those were and for whatever reasons prompt ants to go to such great lengths.

I saw the tiniest grasshoppers I have ever encountered. They jumped, and I laughed like a child.

The wind that had come up the Severn played with my hair and chilled me until I could sit no longer. A raven and a buzzard soared over the site, calling.

I was not magically healed of my pains and woes. This did not surprise me. I did not stay for long enough for that to seem even slightly realistic. There were no revelations, but I do not know the words that were spoken in this place or the songs sung, and there were a lot of tourists, and it seems to be a lot to ask of a place just to wake up for me when there is no one to care for it from day to day or to sing its songs.

I left with no grand tales to tell, and no mission, and no particular insight. I left feeling blessed by the sun and wind, by the ants and grasshoppers, raven, buzzard, and all the small flowers in the grass.

May 30, 2015

For love of land and language

I have a weakness for words. I get excited by terms like ‘crepuscular’. Anything archaic, specific, anything that rolls well over the tongue or identifies something for which I had no words previously. Last week I got very excited about ‘smeuse’ which is a hole made in a hedge by the regular passage of a small animal. If the small animal is a hare, it might instead be a hare-gate.

I have a weakness for words. I get excited by terms like ‘crepuscular’. Anything archaic, specific, anything that rolls well over the tongue or identifies something for which I had no words previously. Last week I got very excited about ‘smeuse’ which is a hole made in a hedge by the regular passage of a small animal. If the small animal is a hare, it might instead be a hare-gate.

I don’t really know how to review Robert McFarlane’s ‘Landmarks’. I loved it. At times I wanted to hug it and proclaim it as my new sacred text. It inspired me and caused me to wonder, and to think about my own relationships with landscapes urban and rural, how I move through them, participate in them, am changed by them. Who I am in a landscape and how I express that have been issues on my mind for a while. This book has not answered any of that for me, but it has shown me doors, alerted me to fellow travellers, given me ideas about what I will walk, read and write in the months ahead. It’s also gifted me with a wealth of new landscape language.

This was, without any shadow of a doubt a book written for me – because I have something verging on a fetish for language and a passion for walking and for the landscapes of Britain and I’m getting increasingly interested in the idea of writing about landscape and a spiritual practice that revolves around being in the landscape.

I hope it’s a book that will turn out to have very wide appeal indeed. As childhood becomes ever less free-range, as we as a society become ever more removed from our landscapes – even the urban ones in which most people are now living – we need our eyes opening. We need to be reminded of place, and that who we are is part of a place and that places shape us in turn. We aren’t little unconnected islands in the great sea of the internet, but physical beings in specific locations interacting with all manner of things that we may have no conscious awareness of at all.

It’s hard to think or talk about something if you have no language for it. Easier to engage with the things we can name, and by naming, discuss with others and fit into the narratives of our lives. The need for narrative engagement with the land is something Landmarks really conveys, and the loss of awareness that goes with the loss of language.

I’ve added water dogs and wonty tumps to my vocabulary, which makes me absurdly excited about the opportunity to point and exclaim ‘wonty tump’ on finding one. I want to learn more about Saxon language in place naming and perambulations – a verbal kind of map making that I learned about from Alan Pilbeam. I want to read more books, and next time I lie in the grass I will think of other adventurers and nature writers who lay down on the ground to better know something it is hard to put into words.

For me, this book was a beginning, a doorway to a path I’d been looking for awhile. Where it goes, I intend to find out.

May 29, 2015

3 strands of revolution

This is a work in progress, but this is where I’ve got to in recent weeks. I see these three strands as interweaving, to create an effect that will hopefully, be more than the sum of its parts.

Strand one: Abundance

In the last few years my household has worked out what sufficiency looks like and what enough means for us. We can and do live very lightly and we know what we need to be psychologically and emotionally sustainable. We will be seeking those things because we can’t help anyone else if we aren’t viable ourselves. We had thought about settling there, but looking at current politics, we are going to take what skills and strengths we have and seek to be better than sufficient so that we have abundance we can share with others who have a need for it. This is not just a money issue, but about all the things we might be able to share.

Strand two: Growing

It’s not enough to bail out people in times of crisis. We have to grow better ways of doing things. More supportive communities, better sharing of resources, more stable ways of living and being. What we’re seeing at the moment is an inevitable consequence of a competitive capitalist system. Other options exist. We have to start imagining them, talking about different approaches, enacting what we can. We need to create contexts in which people can flourish. Much of my attention for this strand will be focused locally but I am (of course!) also thinking globally as best I can.

Strand three: Communing

It’s about a non-consumption orientated way of life that instead favours social interaction, people doing stuff, getting outside. In my case it means walking because that feeds my soul, improves my mental health and generally keeps me viable for doing the useful stuff. It’s about offering other people alternative visions of a good way of life, and sharing our growing understanding of what ‘the good stuff’ is.

This is all about cultural revolution. It’s a three stranded strategy for moving towards a kinder, more sustainable way of life. No rioting required, just some serious shifts in what’s valued, how we spend our time and how we deploy our resources. I will be giving more away. I will be walking with people. I will be living the changes I want to see.