Nimue Brown's Blog, page 322

May 14, 2016

Fiction – The trouble with enchantment

He is the greatest sorcerer for miles around. They always are. He has summoned a fairy. They always do. He believes he can control the fairy. This is why great sorcerers go in for the kind of lunacy the rest of us know to leave well alone.

The fairy had been caught before. When I say “caught” I mean ‘showed up because this shit is always funny’. She is no more afraid of him than a cat is on finding itself ‘caught’ by a rather ambitious mouse armed with a toothpick.

The fairy undulates seductively and offers the sorcerer her most alluring gaze. She does this to wind him up. Fairies pride themselves on being even more heartless than sorcerers, which is going some.

This sorcerer keeps his heart in a box. The box is made from the bones of an especially vindictive satirist, held together with metal, mined in the cruellest conditions by famished orphans. The fairy sees this at a glance, but is not surprised. The previous sorcerer who summoned her had locked his heart in a glacier, to protect it. He lasted half an hour. Before that, was the one with enchanted chains around his body. It did not go well for him.

“Nice box,” says the fairy.

What will this one want? Wealth? Knowledge? Power? Sexual favours? Wizards who have their hearts enchanted into stone, and otherwise unavailable, have a surprising amount of trouble getting laid. You’d think they would be wiser than to go seeking fairy women, of all creatures, to relieve them.

The fairy is bored, so she steps out of the magical circle cast to contain her, and wanders around his potionary. She picks up the carefully enchanted box made of satirist bones.

“So easy to steal! But better if you give it to me freely. Then I can grant you any wish you name. I can grant the wish that is in your eyes but does not reach your lips.”

Sorcerers do not give away their pre-packaged hearts to fairy women. It is rule 147b in The Ancient Book of Doing Sorcery.

Fairy women do not gaze into the eyes of sorcerers and decide to treat them kindly.

She could steal the box that she now holds, and consume this poorly guarded heart with ease. The bones will yield up what they were set to protect, because the bones care not one whit for the sorcerer, and the fairy is persuasive. From his face, she can tell that he has just worked this out, too. He’s too proud to speak, or to ask for mercy. He holds firm, stares her way, and waits.

She has eaten a lot of hearts along the way. Would his taste any different? Fairies do not have books of rules, because when your first rule is to follow your fancy and to hell with the consequences, there’s not much call for a book.

She throws the box back to him.

May 12, 2016

Entitlement and need

To be ‘needy’ is to be a problem to the people around you. We all of course have needs, many of them very similar. We need food, shelter, warmth, water. We need to feel reasonably secure and acceptable to those we spend time with. Most of us admit to needing affection and goodwill from others. Somewhere, a line is drawn, and certain people are ‘too much’. Too needy. If a person is designated as ‘needy’ then dealing with what they need ceases to be anyone’s problem.

It’s interesting to ask who is allowed to need what. Who is likely to have their needs met, and who is not? To what degree is there exchange or barter in the mix? We may be more likely to accept the needs of people we easily empathise with, and people whose needs are convenient and do not require much effort to sort out.

Need has the scope to create a sense of social duty. This can turn into feelings of martyrdom and being put-upon. The more obliged we feel to answer someone’s inconvenient need, the more we may resent them if they cannot obviously recompense us. Much may also depend on the presence of an audience who can be impressed by how good we are. It’s always easier to be kind and generous when you can see how you will benefit directly from that.

It is worth paying attention to who we cheerfully help on request, and who we write off as ‘needy’ and try to ignore. Think about who you take seriously and who you don’t and whether you in turn expect to be taken seriously, or tend to be one of the people whose needs are not reliably honoured.

Of course there’s a political angle to this, too. A politician in the UK can expect to claim thousands of pounds of ‘expenses’ on things most of us would have to fund for ourselves. A person too ill to work is expected to live on far less. What we’re happy to accept that the Queen ‘needs’ is not the same as what we think old people in care homes need.

Often it seems to me that the scope for getting your needs met is directly proportional to your wealth and power. Of course it’s the people with least wealth or power who tend to have the most need.

May 11, 2016

If Women Rose Rooted

I’ve spent rather a lot of the last week slowly reading and thinking about Sharon Blackie’s book, If Women Rose Rooted. It’s a fascinating mix of autobiography, Celtic mythology, the stories of modern women, and the idea of the heroine’s journey.

I’ve spent rather a lot of the last week slowly reading and thinking about Sharon Blackie’s book, If Women Rose Rooted. It’s a fascinating mix of autobiography, Celtic mythology, the stories of modern women, and the idea of the heroine’s journey.

I’ve read some Joseph Campbell, and he’s certainly very interesting, but the reduction of all story down to this idea of a hero’s journey has never agreed with me. Story should mean more than this, surely? I’ve never been able to see myself in the hero’s journey, not even when Martin Shaw reworked it so beautifully in his book ‘Snowy Tower’.

Before this starts to sound like a gender issue, I should flag up that the point at which I really started thinking about multiple narratives, was when, in 2013, I interviewed Ronald Hutton for the Moon Books blog (http://moon-books.net/blogs/ronald-hutton/) Hearing him talk about story and interpretation at the PF Wessex conference recently means this has been on my mind.

Stories shape who we are, and where we are going. What we say and how we say it can define a culture. The stories of the hero’s journey – as Sharon Blackie illustrates – are stories of adventure and conquest, triumph and dominance. These are the stories that celebrate ‘power over’, competition and winning. These stories underpin capitalism and the destructive exploitation of the planet.

I found Sharon Blackie’s book to be a fascinating and rewarding read, full of ideas that resonated with me and lessons I needed to learn. Even so, I’m not going to rush out and restyle my life along the lines of the heroine’s journey either. It’s just too gendered for me. Too defined.

What I am going to do is keep thinking about those other story shapes. There have to be other ways of writing and other kinds of stories to tell. We’ve got used to certain forms and habits in stories, certain shapes and underlying ideas about what a story should be. Not least, we favour stories that are tidy, with clear endings, clear meanings, with winners and losers. I guess people have been telling these kinds of stories for a long time, but perhaps not forever.

More about the book here – https://ifwomenroserooted.com/

May 10, 2016

Going to Granny’s House

Grandmother’s house in the woods – place of challenge and transformation, the place young women go to be turned into themselves. For me, Red Riding Hood’s grandmother and Baba Yaga are almost the same person. Neither of my biological grandmothers lived in cottages in the woods, but in my head, this is the place of grandmothers, and it has an archetypal force to it that I can’t resist.

This is why I’ve got two novels where Granny’s house in the woods features. When We Are Vanished (coming soon) has a grandmother house of transformation, and some uncertainty about whose grandmother actually owns the place! I’m currently chipping away at a novel where a deceased grandmother with a house in a valley plays a similar role – the house is a place of initiation and transformation.

My maternal grandmother’s house was a place of ghosts and cats, a place of hoarded things, where art was made, and cakes. It could be a refuge, or a place of argument and it featured heavily in my childhood. It is not the house I write about. My paternal grandmother lived in a small bungalow, and I don’t write about that space, either.

Grandmother’s house is a place of longing, and belonging. It has mythic and archetypal qualities. Perhaps we crave the fairytale granny who is all smiles and baking. Perhaps we need Mother Holle to teach us how to be women. Perhaps we need to go and ask Baba Yaga for fire.

And so when I write, I go into the woods inside my head in search of a grandmother figure. I’m writing significant absences – I don’t really know how to write this grandmother as a tangible presence, but perhaps that’s part of the point.

Grandmother’s house is somewhere around the next bend in the path. We can smell the woodsmoke. We’ve heard the chickens, although whether they will be cute, domestic chickens or something else, and whether grandmother is really a wolf, we’re still waiting to know. Perhaps we can only know when we become her.

May 9, 2016

Considering the Nature of Prayer

This is an excerpt from the start of my book When A Pagan Prays…

This is an excerpt from the start of my book When A Pagan Prays…

When I first started thinking about prayer, it was very much from a position of intellectual curiosity. In many ways, my prompt was Alain du Bottan’s Religion for Atheists, which explores the social benefits of religious activity. Prayer was notable in its absence from the book. However, the idea of considering religions in terms of what they do in this world, appealed to me. While I am not an atheist, I’m not very good at belief either. In many ways the atheist position seems too much like certainty to me, but nonetheless I find a lot of atheist thinking appealing. Demanding that things make sense on their own, immediate terms rather than with reference to unknowable, ineffable plans, is something I have to agree with. Looking for rational approaches to religion led me to write Spirituality without Structure in one of the gaps while this book was being wrestled into submission.

There isn’t really a fixed modern tradition of Druid prayer. Some groups and Orders have defined approaches to praying, but my impression is that the majority do not. Early conversations on the subject indicated to me that many Druids feel uneasy about what they see as being a practice we can only borrow from other religions. Petitioning the gods for things feels both pointless and wrong. Looking further afield, I found that people generally take prayer to mean petition, unless they are deeply involved with a spiritual path that includes a more involved understanding of the subject. This seems to be true of

people of all religions.

My thinking at this stage was: other religions use prayer extensively and apparently we don’t. Why is that? Are there good reasons to reject prayer, or are we missing a trick? I admit that I thought the question could just be tackled intellectually. Being the sort of person who defaults in all things to getting a book on the subject, I set off to read around.

When I was first looking for books to read about prayer, I poked about online and in bookshops. Books of prayers are plentiful, but not what I wanted. Books that consider prayer as a process are relatively few, although I did eventually track down some excellent ones, and you’ll see scattered references as we

progress.

In a Christian bookshop, a generous woman spoke to me about her own prayer practice. She viewed the urge towards prayer as innate to the human condition. She also found me some books, and did not blink too much when the subject of Druidry came up. “I pray to God as if I was talking to my father. He is my

father. I can go to him and ask him for things,” was the gist of her description. I did not learn her name, but remain grateful for her help. She spoke to me about prayer as something intrinsic and natural, and found it odd I should want a book examining how and why we pray. The shortage of such books suggests that many religious people would agree with her perspective.

From that first book (How to Pray, John Pritchard) a new way of thinking about the idea of prayer began to open up before me. “Essentially it is about entering a mystery, not getting a result.” I found this resonant. The author is an Anglican Christian, but the sentiment struck me as being totally compatible with Druidry as I practise it.

My next read was a Catholic book (Ways of Praying, John C Edwards) by which time it had become plain to me that in some quarters, prayers of petition are considered to be the least important form of prayer, at least by the people for whom praying is a professional and serious business. After that, my reading took me into works from other traditions and I wondered if I would be writing a comparative religion text. However, that would have largely been a rehashing of other people’s work, and I’m not convinced the world really needs something like that.

I had considered surveying the modern Druid community in a more formal way to deepen my understanding of what we do and how we do things. However, my initial enquiries had raised the issue that a significant percentage of the Druids I had talked to were not praying at all. There are some who admit to occasional petitions, and several groups with much more involved approaches. I could get figures for the praying and not praying, I could ask nosey questions about who people pray to, and what they think they get out of it, but how much would that help? This was my first inkling that intellectual research might not be able to shed enough light on the subject. It could easily be like scraping the paint off pictures and weighing it to make judgments about the value of art works. That leaves the anecdotal, and self-reporting, neither of which constitute good science – not even in softer subjects like psychology. I don’t have the kit to study what happens inside people’s brains when they pray.

Why was I fearful of writing a spiritual book about a spiritual subject? It was a question I did not know how to ask myself at the time, but looking back it seems significant.

More about the book here – http://www.moon-books.net/books/when-pagan-prays

May 8, 2016

Escaping the barbed wire hamster wheel

There are ways of talking about paths we get in our minds that are proper and technical and scientific. Just so that you know – I won’t be doing that. I find it easier to talk in metaphor. It has to be said, that the idea of pathways through the mind is passably literal. When it comes to the barbed wire hamster wheel, I may be straying into the realms of the less technically accurate.

The barbed wire hamster wheel is a terrible thing to be on. All you can do is run in its little circle, while the barbed wire flays you. Arriving, and leaving seem, when you’re on the wheel, to be incomprehensible things. More like acts of god, than anything you could have chosen or changed. When on the wheel, with blood and skin flying metaphorically all over the place, it’s almost impossible to be aware of anything other than the wheel.

These are thought processes it is really hard to express in any other way. They don’t obey reason, they aren’t open to recognising cause and effect, they can’t be argued with. The barbed wire hamster wheel has its own truth, and its truth is that you are awful, failing, useless, worthless, and that you absolutely deserve to be trapped in a barbed wire hamster wheel and obliged to run and tear yourself to shreds in it for all eternity. This is what it seems like when some kind of tortured crisis is underway on the inside.

Last weekend I ran for several days in the hamster wheel. I sobbed, and bled, and thought I would be there forever. Usually I get to stop running only because I become so exhausted that I can’t feel anything anymore. This time I stopped running. The difference? I think it’s a consequence of years of being supported in questioning the truth of that wheel, and being encouraged to question why I am running in it.

This week I’ve been able to give it a name (Tom came up with the name for me). In naming it, I have power over it. If those feelings of frantically running in vicious circles come back, I will know what to call them, but maybe they won’t come back, and maybe if they show up, I won’t have to climb inside and start running.

It is a very hard thing to question your own reality. Those questions can seem more terrifying than the wheel does. That’s part of why it’s so hard to get out of the wheel and think something different. But it can be done, and having done it once I at least know that I can do it again.

May 7, 2016

Fiction – To cough up bones

When you found me, my wings were broken. A wild owl will not last long in such a state. But, then, if I was ever a wild owl, I do not remember it. I broke my wings escaping from a cage that fills my entire memory of the past. How did I know a cage could be escaped from? I must have been something else, once. Someone else.

A true owl coughs up pellets made of fur and bone. An act of returning to the world of the bounty feasted upon. Grotesque marvels to amuse morbid human children. My pellets in those early days of freedom were glass shards, barbed wire, and tufts of anonymous plastic, laced with the rank smell of poison.

I was not a pretty owl.

You showed me pictures of owls, and told me about what owls do, because I had no idea anymore. You could not fly for me, but reminded me what wings are for, and gave me the space to use them, should I feel inclined to take the risk.

For a real bird, with snapped bones beneath tattered remnants of feather, death may be kinder than life. There are advantages to not being quite real, and these are the advantages I have, and I must not fear to use them.

On the day I flew, you kissed my feathers, and let me go. Each action equally important. When I can, I will return to roost somewhere nearby, and cough up small offerings that I hope you will find, and recognise. Proper gifts, of recycled mouse. Proof of life.

May 6, 2016

Bardic love and the subversion of romance

We know what romance officially looks like – the chap who brings flowers. The chap who writes a poem inspired by his beautiful beloved. In fact, poke around in the origin of the sonnet, and you’ll find the Petrarchan sonnet is defined in part by being written to/about a beautiful, unobtainable woman.

As a female writer, I’ve always found this a bit of an arse. As a lover, I’ve always found it annoying. I want to write poems and serenade under windows. To be the focal object of someone else’s creativity has never seemed like the aim of the game to me. Sure, it would be flattering, but it’s not my primary interest. An exchange of inspiration is a far more exciting prospect.

And then there’s the whole ‘romance’ issue – this brief part in an early relationship where the man is to bring stuff in order to persuade the woman to have sex with him. Fuck that! Fuck it in all its over-tight patriarchal orifices! But then, we have a history that for too long considered marriage to be consent. Get your woman to make that one big declaration of consent, and you’d never need to woo her ever again.

I like wooing, and courting. Not just as a kind of intellectual foreplay, but as a way of relating to people. As an expression of love that isn’t simply romantic, isn’t just about getting in someone’s pants. I like to praise and admire, and offer up love and adoration, sometimes with rhyming couplets. It’s a whole other expression of bardic love.

May 5, 2016

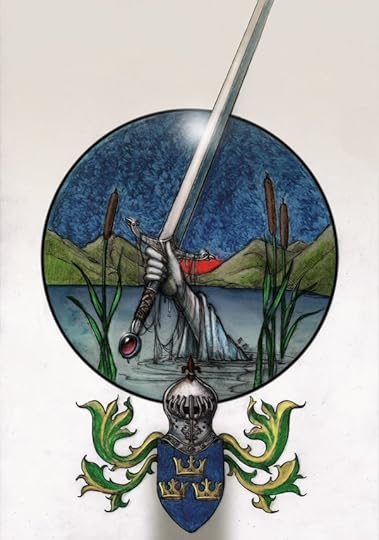

Ladies of the Lakes

The Lady of the Lake raising her arm from the water to offer Excalibur to Arthur is a powerful image, one of the defining images of Arthur’s myths, I think.

The Lady of the Lake raising her arm from the water to offer Excalibur to Arthur is a powerful image, one of the defining images of Arthur’s myths, I think.

Working on the graphic novel adaptation of Mallory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, I’ve been obliged to notice that it’s not just one lake lady. Also, as a personal note, in some versions, Nimue/Vivien is a lady of the lake.

The second, less famous lake lady rocks up to Arthur’s court bearing a sword only a good knight can pull from its scabbard. This is a bit of an evil joke, because the man who takes the sword is then fated to kill someone he loves with it. Swords from lakes may be magical, but they aren’t reliably benevolent.

Who are these ladies? Spirits of place? Half-forgotten deities? Literary plot devices? A bit of minds-eye candy?

As I’ve been colouring on the project, I’ve thought about them a lot. I’d like to offer my unsubstantiated personal uncertainty on the subject. (It’s not gnosis, I really don’t know…)

We know the Celts made offerings to water, including offerings of weaponry. There are sites, in lakes, where lots of booty was thrown in. I think this has to be connected. One possibility is that the ladies of the lakes are a vague folk memory of the lake beings to whom those offerings were made. Another option is that they’ve come into being to explain the underwater hoards. It makes sense if you find a treasure under a lake to imagine it belonged to someone, and from there it’s not very far to the strange women lying in ponds distributing swords as a basis for a system of government.

May 4, 2016

Fiction – Skinned

As an adult, I found the courage to go to the attic room where we keep the boxes. Generations of boxes, each one small and carefully locked. The keys are thrown away. Each box holds a skin, that was taken in the first few days after birth. It’s the only way.

The only way to do what, exactly, no one ever says.

In place of the skin that cannot be kept, we have to make our own. Mine is fashioned from sackcloth, but into the holes I have woven flowers, feathers, bits of string. Spiders find me habitable.

My box has my name on it. I brought a screwdriver, and took out the hinges instead of fretting over the lock. Even so, I had to prise it open. It smelled of dust, and for a moment I thought there would be nothing there, that my skin would have rotted away years ago. I put a hand in, and what seemed like spider webs turned out to have slightly more substance. A tiny, fragile baby skin, soft to the touch, shimmery like moonlight on water.

The skin I am not allowed.

I took off the sackcloth, although it hurt to do so. Flesh grown into fabric, in order to survive. I bled on the dusty floor. I realised I had always been bleeding, somewhere under the fake skin. With raw and seeping hands I picked up my baby skin again, barely large enough to cover my face. Not enough to wear into the world. But it is my skin, as the sackcloth never was.

If this is a fairy tale, then by some miracle, that silvery lost self will grow back, and fit over these flayed shoulders, allowing me to become myself.

In my family, we take off our skins when we enter the world. No one says why, only that there is no other way.