Nimue Brown's Blog, page 290

April 3, 2017

Choosing to Learn

I was very taken recently with Imelda Almqvist’s blog about Trump as a teacher (read it here). Imelda’s underlying philosophy is that we are all here to teach each other. I have a similar line of thought – that everything has the potential to teach us, but it’s up to us to decide what we want to learn.

Any situation can offer multiple outcomes in terms of what we might choose to learn. We could choose to learn from Trump that we can’t have nice things, the world is full of hate and there’s no point trying. It’s not the only possible teaching available, as Imelda points out.

Choosing what to learn is about consciously choosing who we want to be and the direction we want to move in. The trouble is that the vast majority of learning we do through life is done unconsciously. We absorb information from what’s around us and from the experiences we’ve had. Often we don’t dig into it, so we get knocked down by the people who attack us, and demoralised by the shit peddlers and we learn to compete and control and scrap over resources as though they were finite when they aren’t while wasting other resources as though they were infinite… which they aren’t…

Imelda’s blog post is not just interesting in its own right, it’s a map for taking a journey. If we want to choose what to learn, we’ve got to step back and contemplate things, put them in a wider context, delve about in them. A deliberate, contemplative engagement with the choices we have opens things up for us and gives us all the opportunity to take what we need from our experience, not what’s being pushed at us.

April 2, 2017

Mustering Magic

A review by Frank Malone

A review by Frank Malone

The latest book by Philip Carr-Gomm is Lessons in Magic: A guide to Making your Dreams Come True. I always look forward to his publications as Philip is also a psychologist, and shares a common quest: for a spirituality that is more psychological and a psychology that is more spiritual. Highly accomplished, amongst other things, he is head of The Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids – the world’s largest order of Druidry. Psychology and Sprituality meet in the book, which displays Philip’s considerable skill at integrating the two. Similar to the Pagan Portals series from Moon Books, this is one of those brief works (52 pages) that manages to boil down a lifetime of developed wisdom on a specific subject.

In his introduction, Philip states that, “real magic, powerful magic, good magic is concerned with serving something more than yourself, as well as yourself. Real magic helps you make a difference in the world.” From psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut’s Self Psychology perspective, this view of magic could be said to meet the selfobject idealization need. This universal need begins in infancy and persists throughout the lifespan. It is the need to feel part of something bigger than oneself. Further, to “make a difference in the world” is one of the indices of growth that we look to see in our patients in psychoanalytic treatment. I had not thought of it in these terms before reading this book: psychoanalysts anticipate that our patients will become magicians.

I appreciate the personal style which Philip deploys in the text, including history material from his childhood. Of course that is gratifying to my psychoanalyst self, and the part of me that loves personalia about inspiring people.

Asserting that “magicians give birth to dreams” Philip organizes the treatise into five sections. The Arrow of Darkness concerns finding your dream. Nourishing the Seed considers how to suckle the dream. Here he wisely teaches us to “focus on being first. Seek contentment, fulfillment, inspiration, and wonder first. Then focus on doing what you love.” Jumping Off the Cliff and Finding You Can Fly shows us how to ask spirit friends for help. The Daring Adventure is an excellent discussion of how to think about objectives and obstacles. He notes that psychological studies of highly self-actualized people show them “to use both their cauldrons and their wands – their abilities to be both open and focused.” The Harvest reflects on how to live our dream in a way that facilitates a flow of further inspiration.

Lessons in Magic achieves Philip’s aim to seamlessly blend psychology and ancient wisdom. It is recommended with enthusiasm to anyone who wishes to dip into the subject of magic, regardless of spiritual path.

Find out more about the book here – http://www.philipcarr-gomm.com/book/lessons-in-magic/

(I’m always open to guest posts, and providing a platform for people who don’t have blogs.)

April 1, 2017

Tree insights

If you’re a Druid studying the ogham, but you don’t live alongside all of the trees, it’s difficult making a connection with them. In theory, the solution is to swap in a tree local to you that has the same qualities – but without knowing the original tree, this is not an easy call to make.

The Woodland Trust, a UK charity, have done a thing I think Druids are going to find useful and inspiring. They’ve made a collection of small videos each capturing a year in the life of a tree. These are beautiful pieces, well worth watching for their innate loveliness. They also give a real sense of a tree in a landscape and its life through the seasons.

Here’s my absolute favourite, the beech,

And if you go to the The Woodland Trust channel on youtube, you can work your way through many others. Here are the ogham trees available in the set: Birch, Rowan, Alder, Ash, Hawthorn, Oak, Hazel, Crab Apple, Blackthorn, Elder. There are other tree videos available aside from these, so do have a dig about!

March 31, 2017

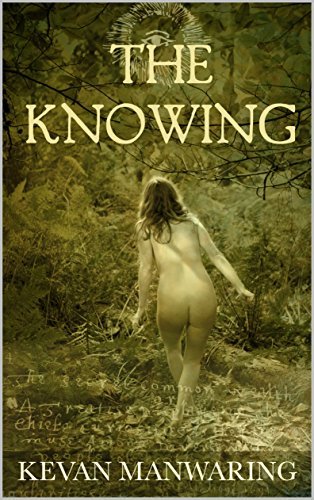

The Knowing – a review

I’ve written some reflections of this book already, here, but felt it deserved a proper review, so, here we go…

I’ve written some reflections of this book already, here, but felt it deserved a proper review, so, here we go…

The Knowing is a fantastic novel, with a lot of different threads weaving through it. The main story follows the adventures of Janey – a young musician trying to sort her life out, dealing with her romantic issues and trying to make sense of her ancestral baggage. Janey’s ancestral baggage is however, far bigger and more dramatic than most of us have to contend with. Janey is also dealing with unprocessed grief from a tragedy of some years before, and with a psychic gift that she doesn’t really want. So, this thread of the narrative is modern, contains modern romance and magical realism elements, and is an engaging tale of personal discovery, healing, growth, friendship and coming into your own power.

Janey’s ancestral baggage gives us the second major thread. The main character works her way back along her female line of descent, discovering the tales that have shaped her family down the centuries, and the influence her ancestors have had on her. There’s a wealth of history here, especially the kind of women’s history that doesn’t normally get much attention. It covers lives of wealth and privilege alongside lives of graft and poverty.

Janey’s ancestral line reaches back to Robert Kirk – a historical figure and the author of The Secret Commonwealth – a key text on the folklore of faeries. Kevan Manwaring has skilfully woven the known history of Kirk and the speculations about him into this tale, breathing life into a very strange piece of history. But he doesn’t stop there, because the landscape Kirk came from is also the landscape of Tam Lin and Thomas the Rhymer – two of the most famous faerie stories out there. Out of the faerie folklore comes a third narrative thread that is steeped in tradition but also full of fantasy and comes as a powerful contrast to Janey’s magical realism narrative.

I’ve read this book twice now, in different orders, and I loved it both times. It is rich and rewarding, highly imaginative, and totally engaging.

Find The Knowing here – https://www.amazon.co.uk/Knowing-Fantasy-Kevan-Manwaring-ebook/dp/B06XKKFGFV/

March 30, 2017

Uncompetitive physical culture

At school, sports tend to mean competition. There’s no accident in this. A fair few activities have their roots in warrior skills – javelin is the most obvious, but all those combinations of running, riding and shooting are pretty suspicious too. Not that we did that at school! Games and tournaments are the traditional solution for keeping your army fit and keen when you haven’t got anyone to fight. Some sports – football being the most obvious here – come out of ritualised contests between villages. The strength, stamina, co-ordination and sometimes teamwork of sport all has military applications

Like many young people, I never got on with sport at school. The focus on competition was a big part of it. There have to be winners and losers, and when you are always, invariably the loser, there’s not a lot of incentive to keep investing effort. Only when out of school PE and able to explore swimming, walking and dancing on my own terms did I become interested in sweaty things I could do with my body.

I have no problem with the competitive stuff being there for people who want it. That’s no different from battles of the bands sessions, short story competitions, produce shows or bardic chairs… sometimes the people who are really good need the chance to test themselves against each other. But only in sport do young people find themselves obliged to do that testing week after week as they grow up. No one would give an English lesson a week over to slam poetry and rap battles.

Physical intelligence has far more going on in it that competition. There is more to building strength, stamina, fitness and skill than being better than someone else. What would happen to physical culture if we approached activity from the angle of health and capability rather than competition? How many young people would be spared from regular and pointless humiliation? How many would become interested in being fit and healthy rather than feeling alienated from physical culture?

But of course governments like team sports, because of the military applications. There’s a popular quote (of dubious origins) that The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton. It’s that kind of thinking that puts competition ahead of health and embodiment.

March 29, 2017

Bardic – creating spaces

One of the things you may be called upon to do as a bard, is to create a performance space. There’s no way of doing this that is right, it’s a case of considering the space, and the intention and nature of the gathering.

If you use a performer/audience model with the audience in rows and the performer(s) at the front, then you elevate the status of the performer and encourage the audience to be an audience. It can take longer to get performers on and off, and if there is more than one performer then someone must act as master of ceremonies and handle the changes. In some venues, this layout raises issues of who can see and hear – a stage is often essential, amplification may be necessary. If there are a lot of people, this is often the best layout to use.

Working in the round puts everyone on an equal footing, there is no ‘front’ and everyone is able to interact, so there’s much less divide between audience and performer. If most of the audience are also performing, this can be preferable, and quicker. It does create a more casual atmosphere, and does not give the same status lift to performers. It can make the space slightly harder to control. In a circle of under thirty people, this layout is viable, but if it gets to be a larger crowd, you may have to have inner and outer circles, which will cost you some of the inherent democracy.

When you’re running a space, it’s good to test the acoustics of it and find out if there are any sweet spots for getting your voice to carry, or any dead spot to avoid using altogether, or encourage the accordion players into! They don’t need any help to be heard.

Never try and run an event from a position of having your back to the door. Make sure you can see the majority of movement in the room. If you’re outside, try and find something to have at your back – a tree for example – so that people can’t creep up on you. To hold a space you need to know what’s going on in it.

March 28, 2017

Not doing Mother’s Day

Mother’s Day makes me profoundly uneasy, so I don’t do it. All the usual things can be said about how it makes life harder for those whose mothers are gone, those whose children did not survive, or never were… and it is a modern festival based on promoting consumerism. But those are not my major issues.

The modern tradition of mother’s day involves kids and/or dads making breakfast in bed for mum, who may be bought flowers, taken out for lunch, cooked for, or otherwise allowed some time off. My concern is that this functions in the same way as the Lord of Misrule and twelfth night carnivals did for feudalism. That basically this is a break from the norm that serves to reinforce the norm. And the norm does not include mum getting breakfast in bed, or someone else doing the cooking. It may serve to enforce the least good things about modern motherhood.

It’s worth noting that Father’s Day involves cards and gifts, but not the same emphasis on the pampering and certainly no flowers. I’ve yet to see a cafe or restaurant advocating that you take your Dad out for a Father’s Day lunch.

There are plenty of stats out there to suggest that while most women now work outside of the home, the majority of housework and childcare still falls largely to the women as well. I don’t want Mothering Sunday as a special day of my family being nice to me. I also don’t need it, because we’re a mutually supportive unit, and I am not the house elf. One day a year of being looked after isn’t enough for anyone, and even if you add the birthday and valentine’s day to the list, it’s still peculiar if you take a hard look at it.

Every day we all get opportunities to be nice to each other, to extend small kindnesses and gift each other in all kinds of ways. Much better that than an occasional blowout for the benefit of supermarket chocolate sales.

I have seen Pagans reinterpreting this day as celebrating femininity, or Mother Earth – I have no argument with any of that. I’m a big fan of people doing what makes sense to them, but I think we should always pause and question anything that becomes normal.

March 27, 2017

A barefoot labyrinth

Those of you who have been following this blog for a while will have noticed that labyrinths have become a key part of my seasonal celebrations. Each one, so far, has brought significant new experiences.

My spring equinox labyrinth was the first one I’ve shared with a sizeable group – and perhaps most significantly, a group where the majority had not been involved in making the labyrinth. I found that quite affecting. There is a big difference for me in making something that is shared.

We used a different location – in the past I’ve built them all at the same spot in a public park – which has felt a bit exposed. This time we were in a very different public space. We were in a graveyard, with the ruins of a mediaeval church, an array of massive Victorian tombs, and the clearly marked square under which lies an Orphic mosaic. The labyrinth went over the mosaic, and coming from a mediaeval church design, seems quite at home there.

I had two striking experiences while walking the labyrinth. The first, on my way into it for the first time of the day, was a visceral sense of how that bit of the labyrinth sat on the ground in the park where we’ve previously done it, and a feeling of sympathy between the two locations.

There were gusts of wind, and at some point after I’d walked my way to the centre, the wind moved something. It’s likely that the other people with me fettled this, but fettled it the wrong way. This being a bigger labyrinth design, it’s not unusual to feel you must have gone wrong somewhere, and that you’ve walked this bit before as the paths fold back on themselves. As a consequence I was there for quite some time before I realised that the labyrinth had changed, creating a closed loop I could not leave. I returned to the centre, and pondered it out, and corrected things. It’s interesting to have the elements redesign the path in this way.

This is the first time I’ve been able to walk one of my labyrinths barefoot. This really adds to the experience, creating a much deeper feeling of rootedness and engagement. It becomes a much bigger sensory experience for having bare feet. It’s also easier to handle tighter turns – some uncertainty about space meant this was the smallest I’ve made the design, resulting in tight turns at the centre where attentive footwork was required – a smaller labyrinth encourages me to go slower, because of the tight turns. A bigger labyrinth creates the room and the incentive to pick up speed.

I don’t know where or when the next one will happen, but I’ve made a proper bag to hold the parts of the labyrinth, and that’s certainly a commitment to doing more of them.

March 26, 2017

The community cost of injustice

There’s an obvious upfront cost to injustice that relates very immediately to whatever has gone wrong. What seems like a small unfairness to someone not immediately affected by it can seem like a small problem, not worth the hassle of sorting out. To the person on the receiving end, that small wrong can be life destroying. However, there is a larger and more subtle cost, one that we keep overlooking. Injustice breaks relationships and undermines communities. All the injustice that stems from prejudice. All the injustice that is intrinsic to rape and abuse. Social and financial injustice. All of it.

So, you’re affected by something, and it hurts you, and damages your life, your wellbeing. I’ll leave it to you to decide what sort of injustice to imagine or remember at this point. Nothing is done. The system refuses to change, the perpetrator is not tackled, no one says ‘hey that’s not ok and shouldn’t be happening.’ You are left with the immediate damage, and the knowledge that no one cares enough to do anything about it. A second level of hurt comes from this, and that hurt can go deeper than even the initial damage.

If your wounding is trivialised and/or ignored, then your relationship with the people who don’t care, changes. It may be that you have to see the injustice inherent in the system, and you can’t ever unsee it and feel easy about things again. It may be that you start seeing all people from the group that harmed you as a potential threat. You will likely feel cut off, and alienated, and angry, and there’s nowhere to take that because the people who most need to know about it have already made it pretty clear that they don’t care.

We’re doing this all the time. We do it at the state level. We collectively turn away from victims. We close our ears to them, we don’t listen to their stories. If we don’t think something would bother us, we decline to see why it would be a problem for anyone else. Injustice severs the natural bonds between people. It dehumanises all of us. When we look away. When we don’t worry because it’s not happening to us. When we say ‘oh, it’s not that big a deal really, stop making a fuss,’ we contribute. And so there is fear, and mistrust, resentment, bitterness, anger all bubbling away in so many places for so many reasons. It’s been there a long time and it won’t change easily, but change it must.

March 25, 2017

Listening to the Undergrowth

Where there is undergrowth, there is life. It may not always reveal itself to the eye, but it will be available to the ears if a person is quiet. This isn’t just about beautiful remote places, but about the undergrowth on the edges of urban spaces, lanes, roadsides, the hedges on fields that are otherwise lifeless monocultures…

We humans have the bad habit of taking our noise with us – be that in earphones, over-involved conversations, or the noise that goes on in our heads. A person doesn’t have to move in careful silence to hear what’s around them – in fact conversation is still possible. What’s needed is more presence. If we fold into the little world of the verbal exchange we’re having, everything around us can go unheeded. If we’re first and foremost present in the landscape, and the conversation is secondary, then the landscape opens to us in new ways. Obviously if you can’t hear at all, this line of thought will be useless to you, but any sound sensitivity can made use of.

People who walk with me have to adapt to this! I will interrupt absolutely anything to point out wildlife, because the wildlife won’t wait for polite opportunities. I’ll break conversation threads for clouds and buzzards, plants and effects of the light. I delight in walking with people who do the same and will leap out of a conversation to alert me to a plant or some other point of interest. (Nods to Robin, if he’s reading this.)

The loudest sound in the British undergrowth is often the blackbird, foraging amongst the leaves. Attention to the sound will lead you to the bird, who is likely close by. Other ground foragers – thrushes, robins, wrens, can also become visible by this means. It is possible to see small rodents if you track them by sound. They tend to be quieter than birds, and sometimes all you can do is track the disturbance of the undergrowth where the rodent passes through.

Mammals tend to know we are around and will often move away from noisy humans before we get any chance to see them. However, if you can move through a space without disturbing it, you may get audio cues about mammal activity. It’s not as easy to see wild mammals as you might assume, but sometimes the sound will give them away. Many deal with humans by being still – in their silence and immobility, we don’t register them, often. But, a moving animal makes sound, and you can hear the movement over the terrain in that sound sometimes, and it is well worth paying attention to.

Of course listening also opens up a world of bird song, wind sound, sometimes water sound and animal cries, but that’s another story.