Nimue Brown's Blog, page 278

August 1, 2017

If we aren’t killed by sea monsters

Sea shanties were part of my life, growing up – my Gran was an enthusiastic singer of these songs, so my memories of them go back about as far as my memories go. Shanties are working songs, creating a rhythm to support the various bits of team heaving and hauling a sailing ship required. Any kind of singing will also help you keep sane when faced with tedious jobs – deck swapping, mending things. When working on boring, repetitive, necessary things, a song will make the difference between being a happy person, and being a miserable resource.

I wrote a sea shanty recently. It wasn’t something I’d ever really thought about before because I don’t spend a lot of time on boats. As a fairly landlocked person, it’s never seemed like something I should be writing. But then it struck me that Hopeless Maine needed a shanty. I’ve been making a lot of things this year that develop and expand on the life of the fictional island, and that’s given me time to explore the details of daily life there.

Being an island, sealife is a key part of the Hopeless diet. However, the sealife is also hungry, and dangerous. The rocks, currents, winds and waves tend to force boats in, so those folk who fish don’t go very far, and spend a lot of time trying not to get themselves drowned or smashed. Or eaten.

In normal sea shanties, chaps make a lot of macho, grunty ‘ho’ and ‘hey’ noises and the odd ‘wuuuh’ to punctuate the song. Hopeless just isn’t that sort of place, which is why, in the chorus, Mr Brown is making more of a groaning noise. And if that leads you to think that we must have a rather odd sort of home life… yes, yes we do.

July 31, 2017

The Parallel World of Pain

My understanding is that for many people, pain is not normal. It’s a sign to stop, to rest, to not start things. Exhaustion is another thing that many people take as a sign to quit. I’ve had conversations where people have told me things like how terrible it would be if you hurt yourself doing exercise, and that I shouldn’t do something until I’m entirely well…

For most of my life, if I waited to be pain free, not exhausted and feeling well, I’d never get to do anything. The only way to exercise is to deal with a body that hurts before I’ve even started. If I want to do anything much, I have to push. Sometimes it feels a bit like living in a parallel universe. People I encounter have such a different experience of life, such different assumptions about what’s ok and what isn’t. I know it’s not just me.

It’s easy to imagine if you see someone doing something, that they’re fine. No one can see what it costs, at the time, or afterwards. Sometimes I choose to pay that cost, because otherwise I don’t get to dance or do longer walks.

There’s an ongoing emotional cost to pushing a body that hurts into doing things. People who live in the parallel world of pain can have very different emotional experiences from those who don’t. It may be that you get by through learning to tune out your body. It’s awkward for someone with a nature based faith where embodiment matters. It’s emotionally exhausting, and leaves you feeling like you’re less than the people who can afford to be present all the time. Sometimes, you end up so out of it that you can’t really think because there’s so much to tune out.

Living in the parallel world, it is hard to make choices about what is and is not a good idea. The regular road map for the territory assumes you are well. How much sleep, exercise, food, rest etc you officially need isn’t much use, but there’s really no one to tell you what might be worth considering. What’s the right balance for a body that doesn’t start from the assumed position of a morning?

We only have our own experiences to guide us. This means that for a person in the normal world, where pain is occasional and the rules for dealing with it are clear, people in the parallel world are confusing. I don’t think it’s possible to imagine what long term pain does at a mental/emotional level if you haven’t endured it. I also don’t think it’s easy to understand the rest of the life impact either, not without making some effort. It helps when people can recognise that there are other people whose experiences are totally different from their own.

We’re not making a fuss. We tend to make far less fuss over pain experienced than people who are generally pain-free do if hurting. We’re not doing it for attention. Whether you think we have low pain thresholds or not, is irrelevant. We don’t want unsolicited medical advice from people who have no real experience to draw on. We don’t want to be told what to do. We don’t want to be told that we should be more positive, more grateful, or that like attracts like and we’re doing it to ourselves. These are not helpful suggestions, they are toxic acts and as cruel as they are unreasonable. If you don’t understand what’s going on, consider that we live in a parallel universe and the rules are different here.

July 30, 2017

Forgiveness Meditations

Trigger Warning: Body shame and body dysmorphic disorder type issues. These are meditations designed to help with this, but I didn’t want anyone to wander in unawares.

I’ve never had a good relationship with my body, and have a great deal of internalised guilt, shame and hatred around how I look. I’ve been working with a meditative approach for a while now, and I’ve found it helpful. This is a broad explanation, you will likely need to fine tune it to suit personal needs and issues. Be really alert to not letting words in that reinforce the problem rather than easing it.

I find this is easiest lying down, but again, adapt as makes sense. Pick a quiet, safe environment. Do whatever you do to enter a calm and meditative state. If you can, put a hand on one area of yourself that you have a problem with. Just stay there for a while, and breathe slowly with it. Focus on being calm.

I started this process simply being repeating the words ‘I forgive’. Inevitably this can cause memories and feelings to come up, so I took to creating a longer stream of thoughts. “I forgive, I accept, I let go,” works for me. I’ve found if I try to use really strong positive words ‘love’ for example, I am more likely to panic myself. “You are ok, you are good enough, you are acceptable” is more effective for me than anything I cannot accept. I don’t do well with conventional affirmations, suggesting to myself that ‘I am beautiful’ makes me feel panicky and sick. It’s not a good idea to try and run when you can’t walk.

The nature of your relationship with your body will inform the kinds of words you need to use, and if you explore this, you may find things emerge for you that you can work through in this way. It is essential to be able to hold clear intent around self-acceptance, and not let abusive, corrosive language slip in. You don’t have to make excessively enthusiastic statements about yourself, and you may find it easier not to, certainly at first. “This is my body and I accept it and am ok with it” is a very powerful, affirmative statement if you have a lot of trouble owning and accepting your physical form.

Ideally, you need to think about what would be helpful without getting too bogged down in the problems themselves. I find that one body area in a session is plenty to be working on, and that moving around different areas of shame and discomfort over different sessions is helpful. It can bring things up so I only do it when I feel equal to dealing with what emerges. I usually work quietly, but saying things out loud is also powerful and worth exploring.

July 29, 2017

Contexts for depression

One of the things that makes it difficult to ask for help around depression, is that depression takes away any feeling that it is worth asking for help. It leaves me feeling that I am worth far less than anyone I might inconvenience with my distress. I feel that it would be better to make no fuss, to hide it, or to go away. However, alongside this it is worth noting that most depression is caused by experiences, not body chemistry, so not being able to ask for help usually means not being able to do anything about the source of the problem.

I blogged recently about anger and humiliation, and it’s become apparent to me how this intersects with depression. It’s often said that depression is anger turned inwards, but it is also the experience of dealing with people who get angry when you express difficulty. It’s being afraid to say there’s a problem in case you bringing it up is a bigger issue than you being unhappy. If the angry defensive response of the person who hurt you in the first place is likely to be even more harmful than the original harm, you soon learn not to say anything.

The person who has gone a few rounds with people who didn’t care, wouldn’t deal with issues, only wanted to be comfortable… that person learns not to make a fuss. They learn that their mental health is less important, while other people being comfortable at all times is more important. They learn that they are not worth as much as the people who get angry with them. The more exposure to this you get, the more you are likely to internalise it. The more you internalise it, the more likely you are to beat yourself up, not seek help, and view any situation in which your ‘illness’ has made someone else uncomfortable, as a potential threat to you.

As a culture, we make depression an issue for the individual, with cure a personal thing to sort out. I can say with confidence that it is nigh on impossible to fix this kind of dynamic while being in it. This is an example of the sort of thing where the behaviour of third parties can change everything. Do you encourage people to paper over the cracks, not make a fuss? Do you take people seriously if they admit they have a problem? Do you step in if one person seems to have far too much of the power in a situation? Do you challenge people who won’t look at their own issues or do you tacitly support their behaviour by staying silent?

When we do nothing, we support the person with the most power. When we do nothing, we facilitate the aggressors and bullies, and the people who refuse to take responsibility for their actions and inaction. Not getting involved is not an act of holding the middle ground, it is not an act of neutrality. Doing nothing is how we help bullies carry on, how we let abusers off the hook, and how we fail to tackle people who, unwittingly perhaps, are really piling the shit on those around them. Doing nothing and saying nothing sends a clear message that we have no problem with what’s going on. If more people were willing to be a bit uncomfortable now and then, many people would not have to spend their lives mired in utter despair and misery.

July 28, 2017

The courting of poems

Everyone who writes will have their own process, or more than one way of bringing words together. For some it’s all about jotting down notes, mapping out ideas, sketching, doodling, trying things and putting together the bits that work. It’s rare that a good piece of writing comes together fully formed and straight onto the page, even those of us who don’t do much development writing expect to have to edit and tidy up whatever emerged in the rush of inspiration.

For me, a poem usually begins with a seed idea. That can come from absolutely anywhere, so of course every single day is full of hundreds of things that might be poems. There’s an unconscious selection process that makes me latch onto some things and not others. A sense of possibility, of something I can follow and develop is usually part of this, and I notice it happening even though I’m not in deliberate control of it.

Once I’ve got that seed idea, I’ll hold it for as long as it takes. Usually a few days, but sometimes longer – months, in a recent case. I’ll think about the idea I’ve got, feel my way around it, see what it connects with. I won’t pick up a pen and risk catching it on paper before it is ready, and I’ve learned that it pays not to rush. I’ll play with word arrangements in my head, testing turns of phrase against the idea.

For example, I recently posted a poem called ‘The Use of Cauldrons’. It was a response to the OBOD work I did with Taliesin more than a decade ago, and to Lorna Smithers’ The Broken Cauldron, which I read last year, so I’d been gestating unconsciously for a long time. I simply woke up with a sense of how to write about cauldrons. It then took several days of just letting that wash around in my brain, and then I was able to sit down and write a decent first draft fairly quickly. I left it alone for a couple of days and then tidied it up. A second poem written recently was sparked back in the winter, I knew what I wanted to do but not how to do it. Again, there were unconscious processes, and then an invitation to read locally, and things fell into place.

For me, the process of creating a poem begins long before pen meets paper. I can’t manufacture those little seeds of inspiration that stand out, and have the potential to become something. They are a consequence of richness in my life – that can come from time spent outside, time with friends, time being inspired by other people’s creativity and anything else with that kind of depth and intensity. If I don’t deliberately make room for that kind of experience, then there won’t be the ‘ping’ moments that give me something to write about.

July 27, 2017

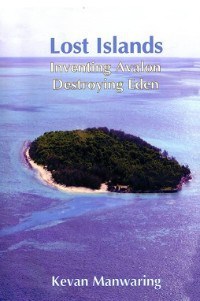

Lost Islands

Those of you who know me will know that I’ve been a fan of Kevan Manwaring’s work for the best part of a decade. And if you’ve been reading the blogs for a while you may also have picked up that one of the things I do is write a graphic novel series set on an island that is cut off from the rest of reality. Hopeless Maine, as Walter Sickert put it is ‘an island lost in time’.

Those of you who know me will know that I’ve been a fan of Kevan Manwaring’s work for the best part of a decade. And if you’ve been reading the blogs for a while you may also have picked up that one of the things I do is write a graphic novel series set on an island that is cut off from the rest of reality. Hopeless Maine, as Walter Sickert put it is ‘an island lost in time’.

It’s a terrible thing to have to admit that I’ve only just got round to reading Kevan’s Lost Islands book. I read it in July because I’m thinking about writing more in the Hopeless Maine setting and I knew it would help me think around that.

One of the things I love about Kevan’s work, taken as a whole, is that he doesn’t sit tidily in a single, neat marketing definition, and seeing him do that has helped me take a similarly unboxed approach. Kevan writes poetry, non-fiction, fiction, he’s a performer, teacher and storyteller, and all of this feeds into any given book. Lost Islands brings together that breadth of experience and insight. This is a book of myths and history, geography, geology, politics, pop culture, literature, personal experience, speculation, science, and even a bit of fiction for good measure! It’s the sort of book that would sit well next to a Robert McFarlane title.

Lost Islands offers a lot of thoughts about physical islands – those that were imagined, may have existed, have definitely disappeared and those that are just very hard and dangerous to get to. It’s also a book that explores the idea of islands in the broader sense – things cut off and surrounded by something other. The driving narrative of the book explores the human desire for the pristine, Eden, and the way in which our search for it destroys not only those pristine environments, but piles on the environmental damage for the world as a whole. There are too many nature writing books out there that encourage us to run off looking for unspoiled nature, and thus to spoil it, so it’s really pleasing to see a book tackle this issue head on and pull no punches about the implications of getting away from it all.

For me, reading Lost Islands generated some fertile lines of thought about how I might map and chart something I’ve set up to be unchartable. Kevan’s recent blog posts have been all about long distance walking, so I’ve been thinking about that, too. I’m thinking about the issue of utopias and dystopias and the desire for something that is not those things. A playground, where you can gleefully run wild but may fall on your face, or be eaten by monsters.

It’s not an easy book to find, your best bet appears to be Speaking Tree

July 26, 2017

Working with the system

Most of the systems that countries depend on rely on our engaging with them. The police are a good case in point here. There are generally not enough police in most countries to apply law by force, and if people don’t consent to be policed, they stop being effective. People who consider the police to be fair and reasonable will consent to being policed. When people think their police are corrupt, unjust and unreasonable, they won’t cooperate.

The same can be said of tax systems, border control, customs and excise duties, benefits systems and so forth. Give people a fair system and the vast majority of people will deal fairly with it, will self-report fairly, and so forth. Give people a corrupt or unfair system, and many more people will be inclined, or obliged to try and cheat it.

If the system appears to be unfair, cheating it can feel like justice. If you can’t trust the system to treat you fairly, there’s no incentive to cooperate with it and every reason to try and fudge things so that you get what you need. Why should I pay my tiny amount of taxes (this is a rhetorical question) when big companies who owe millions, don’t?

However, it’s noticeable at the moment than many systems in the UK are skewed towards trying to catch out what had been a tiny minority of cheats, and do so at the expense of fairness to the majority. By this means, many more people are moved towards not co-operating, and as a consequence the whole thing becomes ever more corrupt. Our benefits system pushes people to the edge and over it all the time. Survival depends on playing the system, taking cash in hand work, and for some people, theft. Given the beliefs and attitudes of our current government, a punishment-orientated, ever less fair system is likely to result from this.

Treat people as though they are good, decent and likely to do the right thing, and the vast majority of us will. Treat people as though they are suspect, make it hard for them to sort out what they need, and you give them little choice but to cheat you in order to get by.

July 25, 2017

Druid Community

Is there such a thing as Druid community? It’s a question I’ve revisited repeatedly. I’ve been a member of The Druid Network and Henge of Keltria – my inclusion or exclusion dependant largely on whether I am willing to pay for membership. Technically I will always be a member of OBOD, but unless I pay for the magazine, I don’t have much direct contact. I believe there are boards I could use, but I spend too much time online as it is. Experience of physically meeting up in groves and groups has also demonstrated to me how easy it is to come in, and to leave.

Communities have to have permeable edges. If people can’t come in, or move on, then you have something stagnant and unhealthy. But at the same time I think that it’s too easy to solve things by leaving, by letting people leave, and thus by not really sorting things out at all.

For me, community means working together to maintain relationships. It’s not simply paying to access the same space, or temporary allegiances. Community means dealing in some way with our conflicts, differing needs, issues and so forth, rather than rejecting anyone who isn’t a neat fit outright. How far we are willing to go to include and to look after each other is a question I think we need to be asking.

Thanks to the internet, and to modern transport most of us aren’t obliged to deal with the Druids around us. There are no real pressures on us to work together. And if the ‘problem’ just leaves, problem solved! I think in this way, Druids are simply reflecting the rest of how things work generally. We move on, we leave jobs, we move away from difficult neighbours, we cut off friends we’ve fallen out with… These are all things that individuals in conflict have little scope of handling well.

Peace is something we talk about a lot around Druidry, but it’s not something we all practice. We don’t all seek peaceful resolutions for each other. We don’t all tend to intervene to resolve things, we often just let the problem move on, or encourage it to. Let the awkward person go somewhere else. Let the person who lost the argument quit.

Mediation is hard work. It can call for challenging people, and for investing time, care and effort in trying to resolve things. To do it, we’d have to really care about each other… like we were some kind of community or something.

(I expect there are Druid communities out there that do this for each other, but mostly my experience has been of the other sort of thing.)

July 24, 2017

Anger and humiliation

Put in the same sort of situation, some people respond with defensive anger, and others feel shame, humiliation and guilt. As far as I can make out, the response has more to do with the person than their circumstances.

The person who is defensively angry often won’t take responsibility for things gone awry. They don’t change, or it will take a great deal of pushing to persuade them change is in order. The plus side for them is that they maintain feelings of personal integrity and worth, they don’t end up doubting and mistrusting themselves, they are more confident and remain able to stand their ground.

The person who responds with guilt, shame and feeling humiliated will try and change themselves to fix things. They’ll take responsibility, even when there’s nothing they can really do. Humiliated people lose confidence and self esteem, and become less able to protect their own boundaries. There will be times when being able to learn and change things will be to their benefit, but often this kind of response will be costly.

Put together two people, one who does defensive anger and one who does guilt, and what will happen is that one party does not change at all, and the other becomes responsible for everything. If it’s easy to make the humiliation-prone person responsible for everything, then the defensive person may become even less inclined to keep an eye on their own responsibilities.

Put two defensive people together and you’ll get a lot of arguments and not much resolution. Point scoring and trying to blame the other will feature heavily, but things will only change if one person succumbs to being the guilty party. The most likely resolution is to pull away from each other.

It’s when you put two people who can be shamed and humiliated together that you can see what’s going on. Two people who take things to heart, take responsibility and are prepared to change in order to fix things, will negotiate. They’re more likely to try and figure out what the real issues are, rather than just trying to blame each other. As both are likely to feel responsible, they will look for ways to work together in order to create solutions. When two easily humiliated people are working together, the net result is often not one of humiliation, but of cooperation and real change.

I’ve noticed bystanders are often persuaded that the defensive anger equates to innocence and those who are shamed are guilty, and this doesn’t help at all. How people respond is a reflection of who they are, and not a reflection of what happened.

And most things, it has to be said, are better dealt with by working together rather than blaming, or making one person entirely responsible.

There is scope for choice here, in the moment of discomfort. Do we make space to look at it and see what we could have done better? Or do we throw up walls and refuse to engage, lashing back at the person who dared to make us feel uncomfortable? In practice we all need to be able to field both responses, but for many of us it’s one or the other.

July 23, 2017

Notes on creativity

Those of you who have followed this blog for a while will know I’ve had ongoing struggles with creative work. The creative industries are a mess, austerity means many people can’t afford books, art or music. It’s really hard making a living at the moment. There’s only so much time and energy available to me. However, over the last six months or so I’ve learned a lot of useful things about staying creative, so, here’s what’s been helping me get moving again.

Not using writing to pay the bills. It’s incredibly stressful and requires a rapid output, which I have found depressing and exhausting every time I’ve tried it. I am more likely to make money from writing if I write the things I want to write and then try to find a home for it, and not have making it pay be my primary concern. If I’ve got my responsibilities to my family covered, I feel freer in my writing, and other forms of creativity too.

Peer support. Knowing it’s not just me, it’s not my failing but an industry-wide issue. Feeling recognised and respected by creative people I admire and respect helps maintain morale.

People to create for. For me an art is only complete when it encounters someone else. A book no one reads is unfinished. People to write for give me a sense of hope and purpose. This blog helps me keep going, I’ve also felt really inspired as a consequence of support for my Patreon. It’s more about people wanting my work than the money, but the money helps.

Making headspace. I can do the disciplined churning out of words, but to really create I need time to daydream, wonder, question and whatnot. I need time when I’m not directly using my brain for other things. I need to be ok with apparently doing nothing in order to make a space for inspiration to come in.

Time to study. I need raw material to use creatively. This means reading, experiencing, learning. I need time to take workshops or lessons, time to pick up courses – not all of it directly about writing, either!

Opportunities to be inspired. Other people’s books, live music, theatre, film, walks, good food, nights spent dancing, conversations with friends, beautiful landscapes… If I don’t feed my soul, all the time, then I can’t create. Get this right and I’m much more likely to be inspired.

Put that together and what you get are creative friends I can spend time with, whose creativity I can be inspired by and who are up for reading my stuff as well. People to walk with, cook with, hang out with, go to gigs with… and as there’s been a lot of that in my life in recent months, it turned out all I had to do was start making better spaces for myself, and putting down things that don’t serve me, and creativity becomes a good deal more feasible.