Nimue Brown's Blog, page 242

August 3, 2018

When there aren’t two sides to a story

Suggesting that there are always two sides to a story may sound entirely reasonable, but I think it’s a notion that could stand some scrutiny. That the Flat Earth Society persists in stating that the world is flat, does not mean that they have an argument worth listening to. When the science is all on one side, and unsupported opinion dominates on the other, we are not looking at a two sided story, we’re looking at fact and fantasy. This is very much the case with climate change, where there is a consensus amongst the vast majority of scientists, and yet the other side of the story – a tiny minority – is given a platform to speak.

We live in an era that doesn’t discriminate between evidence based information, and opinion. It doesn’t help that the opinion side of any story will usually claim that there would be evidence to support their version if only the evidence side did their job properly. If the ‘facts’ are skewed by biased researchers, of course we shouldn’t trust them. The way that the tobacco industry successfully hid the dangers of smoking for so long is a case in point about how asserted ‘facts’ can turn out to be nothing more than marketing.

So, how do you tell if you’re seeing something reliable and evidence-based, or something that’s been paid for? Actual science tends to be wary of asserting facts. It offers theories that are open to change as new things are learned. Science tends to deal in probabilities, not certainties, so proper science can sound a bit cautious, even when its 97% sure about things. People working based on opinion tend to sound a lot more confident, which in turn can seem far more persuasive.

If you’re looking at something evidence led, there may be uncertainty over how best to interpret the data. You may get more than one possible interpretation. You may get questions raised about whatever hasn’t properly been studied. If someone asserts that they know what the data would look like if only someone did the proper research, there’s every reason to be wary.

When considering whether there could be two sides to a story, we have to consider the reliability of our sources. This is not an easy process, and the less education you have, the harder it can be to assess what might be reliable. You can end up mistrusting all authority and so called ‘experts’ if you’ve got no means of telling which ones are being as fair as they can be, and which ones are playing you for their own ends. That mistrust can then be played on by people who do not want you listening to good information, and people who want opinions to be as important as evidence. When those of us who have the privilege of better education and sharper thinking skills denigrate people who are more easily persuaded by less rational things, we feed into this. Denigrate a person and they have no reason to trust you.

Not all opinions have equal weight, either. The opinions of people who want more than their fair share and who want to hurt and harm others do not deserve to be accepted as valid. The opinions of people who are known to lie and manipulate for their own ends, do not deserve to be taken as seriously as the opinions of someone who has always acted well. People who have done the wrong thing, or who wish to exploit others, will say whatever they think it takes to get them what they want. It is in their interests to persuade you that there were two sides to this story all along. The apparently less tolerant person who won’t accept there could be two sides isn’t always the bad guy.

People who are working with evidence can and will show you their evidence. It takes more work on our part than listening to a sound bite. People who have no evidence will ask you to accept that they know best. They may offer that which is clearly too good to be true. They will assert that their evidence exists and that only prejudice keeps the data from being properly collected. They will be more likely to rubbish their opponent than tackle the details of the argument.

Sometimes there aren’t two sides to a story. Sometimes there is no debate to be had, and nothing worthy of being explored. Sometimes there is evidence on one side, and noise on the other. If you aren’t sure who to trust, ask who will benefit and in what ways, should you believe them.

August 2, 2018

Plastic and privilege

I’m always in favour of people being the change they want to see in the world. I think it’s an important place to start with any kind of activism. If you believe it, you live it. However, often there’s a massive privilege aspect to being able to walk your talk.

If you don’t need plastic straws – and most of us don’t – then giving up straws to save the planet isn’t that big a deal. It’s a small sacrifice. However, for disabled people who need straws for drinking, for whom paper isn’t durable enough and washable straws are problematic, giving up straws isn’t so simple. Of course most of us should do without them, but making life difficult for the disabled is not the answer here.

If you’ve got plenty of money, then buying loose veg and going to your farmer’s market is easy. You may have to drive to get there and to carry your plastic-free goods home and you’ll want a big fridge to keep them in. How green is it? And if we berate the people who can’t afford to do that, is that going to help save the world? If all a person can afford is the 45p bag of carrots, and doesn’t have a car to drive them home in and can’t afford to run a fridge to keep them in… complaining about the bag seems to be the wrong place to focus attention.

If being green is a game for the well to do, in between flights to nice places for holidays, then it’s pretty meaningless. As poverty is a real barrier to living a greener life, there has to be political change. There has to be change that makes it easier and more affordable to be green.

There’s usually some bright spark on hand to say that the poor should try harder. That it isn’t so difficult to do this and that and save money here and there and really, you don’t need the things you think you need. The reality of living in poverty is that it is mentally and emotionally exhausting. It’s hard getting good food every day when money is tight. And when you have to watch every penny and cost up everything it takes a toll, and yes, a few pence here and there on the cost of things can make a difference. It’s easy for people who live in comfort to talk about what they think everyone else should be doing, but that’s not good activism. And no, the farmer’s market is not affordable, and no, not everyone can grow their own veg.

It is certainly true that if everyone acted differently, a lot of environmental issues could quickly be solved. Inspiring, enabling and uplifiting people so that they can live more sustainable lives, is a good thing. Blaming those who are least able to make changes, is not cool. And if you’re jetting off to other countries a few times a year, I’m not convinced that your organic fruit is much of an offset. Green living as an affectation doesn’t fix anything, and it can serve to entrench injustice and blaming the victims of an unjust society.

Do what you can to make changes in your own life. Share things that work – especially things that really are low cost. Go after the people with the power to make changes, not the people with least power who are easiest to harass. Remember that if it’s easy to be greener, there’s privilege at play – wealth, opportunity, resources, skills, education, energy, and so forth. Seeing what personal advantages you have that enable you to be green is a good place to start if you want to tackle the issue of why other people aren’t doing so well. We need to lift each other into more sustainable ways of living, and we need to ask most of those who have most.

August 1, 2018

Good Friends

I think it’s interesting to ask what makes for good friendship. I expect a wide range of answers are available, as we all have different feelings and needs. Is friendship a description of a relationship? Or might it be something we do for each other? You can choose to be a good friend to someone when very little is offered in return. You can choose to act as a good friend to someone in the short term to help them in some way – this may be someone with whom you will not have an ongoing relationship. How much give does friendship call for, and how much reciprocity?

While it can be tempting to think of friendship as an arena in which we can heroically practice the art of sacrificing ourselves for love, massively one sided relationships do not do anyone much good for the longer term. It can be really demoralising feeling that people stick around to help you because they feel sorry for you. A relationship based on pity, and on other people being heroic, is not a good relationship to be in. That kind of friendship can help a person feel small and stay put, or it can create weird power flows around who has the biggest crisis, the most problems etc.

For me, the most rewarding friendships are based on mutual enthusiasm – liking what a person does and how they do it, how they think and respond and how they are to be around. We don’t have to be doing anything for each other if we can enjoy doing things together. That in turn is underpinned by care and respect. I think highly of my friends, and over time, what they do justifies my belief in them. I care about them, I care about their successes and setbacks, their aspirations and challenges. I like to be cared about in these kinds of ways, as well.

There have been people along the way who clearly didn’t respect me or much care for me, and wanted me to know what hard work I was. People who have to tolerate me in some way or find me a struggle. I’ve no idea why anyone thinks that kind of self sacrifice is attractive. If you don’t like me, move on, with my blessings. I don’t need to be put up with. I don’t need people having to make a massive effort to cope with me. I’d rather be entirely alone than have that role in anyone’s life. Not that this has ever been necessary.

When we run on a scarcity model, it can be tempting to hang on tight to anyone who stops long enough to let us do that. When we imagine there won’t be many people we have anything in common with. After all, how many queer pagans with an interest in comics can there be in a small town like Stroud? (Plenty enough, in case you were wondering). How many creative people are there in a small town like Stroud? (more than I can get to know). How many druids are there… and so on and so forth. For any of the things that matter to me, for any of the overlapping areas, I can find people. I don’t think Stroud is that exceptional. Interesting people are everywhere.

How much do we owe it to people to include them? How much do we owe it to each other to provide one sided care? How much should we make ourselves available as resources, and make what we have available? How much crap should we tolerate from each other in the name of friendship? There’s clearly no one right place to draw the lines here, but the act of drawing lines is important.

Humans are social creatures. We all have a need for care and contact. Draw your lines in the wrong place, give too much in exchange for little or nothing, and it will eventually wear you down. No one is an infinite resource. Ask too much of the people around you and you’ll find they can’t sustain it. Accept too much of the shit and you’ll take damage. Dish out too much crap and people will move away from you. We all have hard times and rough patches, and we all need to be supported through those, but friendship requires balance. It calls for respect, for mutual concern, and for scope to take delight in each other. If we do not find joy in each other’s company, it isn’t going to function as a friendship.

July 31, 2018

What is treason?

Treason, and traitor are words I’ve seen bandied about a lot of late, especially with regards to anyone in the UK who remains in favour of the EU (about half of us, if not more). Treason is an interesting concept that could use a more careful look.

Historically, treason is a feudal concept. Treason is the betrayal of your monarch, and by extension, your country. It comes from rebelling against the monarchy, and it is easily used to get rid of people the monarch doesn’t like. Anne Boleyn was executed for treasonous adultery, for example. As it’s a punishment primarily affecting power hungry nobles, and thus also potentially benefiting other power hungry nobles, it’s not been greatly challenged in history. And of course challenging the notion of treason would bring you dangerously close to being treasonous.

Rather revealingly, there’s also a thing called ‘petty treason’. This is the crime of social disruption and attacking the hierarchy – if a wife killed her husband or a servant killed their master, they would be executed for petty treason.

Democracy allows us to challenge and question authority. It allows us to ask for change without risk of death or injury. At least in theory. Having radically different political ideas should not be considered treason, nor should honest mistakes that lead to significant problems. In a democracy, what should we consider treason? Clearly it can’t be about affronting the monarch any more.

I think for something to count as treason now, we’d have to be looking at the deliberate betrayal of a country as a whole in a way intended to cause harm to the citizens, infrastructure or viability of that country. However, to distinguish treason from cock-up I think there would have to also be an element of benefit to the people undertaking the action. Destroying the land and polluting the water for the sake of personal profit (fracking). Ruining the economy so as to profit from short selling currency and shares. Being paid by a foreign power to harm the country. Putting life in danger by putting personal profit ahead of environmental safety. These, for me, would be modern acts of treason.

I find it strange that people can get away with destroying the fabric of the land for the sake of private profit, and that not be considered an assault on the country as a whole. Yet at the same time, people who are pro-Europe are labelled traitors.

July 30, 2018

And very little happened

Being a Pagan blogger creates (for me at least) a certain amount of desire to come back with a good story. I was hoping to write about the lunar eclipse this morning. I sat out on a barrow above the Severn, I watched the sun set (as much as the clouds would allow) and I couldn’t even see the moon, much less any part of the eclipse. Today I do not get to write a blog about how beautiful and meaningful I found the night sky on Friday.

I also find this is often the way of it when I go somewhere more as a tourist than not. If I’m going somewhere once, or not very often, even if I feel like it’s pilgrimage, I’m always going to be mostly a tourist. It is daft to expect that I can rock up to a sacred site and have an off the peg, personal, meaningful experience. It’s especially suspect if we think our experience as a tourist gives us more authority than someone who has lived near and worked with a site for a long time.

Landscapes reward relationship. It doesn’t matter whether there’s a famous historical monument there, or not. Landscapes reward people taking the time to get to know them. They reveal themselves slowly, over time. I think we need to be suspicious of anyone, and most especially ourselves, walking into an unfamiliar place and getting a big, dramatic revelation. Especially when the main impact of the revelation is to make the person having it look shiny and important.

When you’re working with intuition, and looking for magic, you have to be alert to what could be ego and imagination. You have to be alert to what you’re taking into a space and how that might colour your experience. I think we also need to be alert to the ways in which talking about what we experience can create a form of spiritual inflation. If you’ve read a lot of woo-woo stories about other people’s amazing and dramatic spiritual encounters, will you feel comfortable saying that nothing happened to you? Or that a very small thing happened to you?

Coming down off the hill on Friday, I turned at the right point to see the moon, low over the hill and briefly free from cloud. Even so, the moon was partially obscured. What showed was large, low and yellowish. The eclipse had long passed. Off to the right, there was a planet and my little party was not sure whether this was Venus or Jupiter. Not knowing felt perfectly comfortable. I’m glad we saw the moon, and I wish we’d seen the eclipse in all its drama and beauty. But at the same time, the land desperately needed those clouds and the days of rain that followed. I watched the clouds coming up from the south and knew they were bringing much needed rain, and was glad to see them.

There is a power in showing up. There are things that happen when you keep showing up to places, open hearted and not expecting too much. There’s a process, and it leads to small wonders and a greater overall sense of the numinous. It doesn’t always lead to good stories or even to things that are easily put into words. There’s a lot to be said for being a person in relationship with the land and I think it’s better for us than focusing too much on stories that put us centre stage.

July 29, 2018

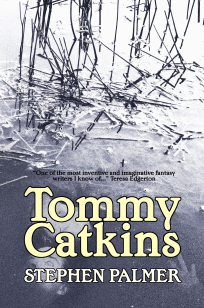

Tommy Catkins – a review

Tommy Catkins is the new novel from Stephen Palmer, whose Factory Girl Trilogy I was very taken with. It’s a story that mixes history and fantasy, and does not encourage you to feel confident about what’s real, and what’s delusion brought on by trauma.

Tommy Catkins is the new novel from Stephen Palmer, whose Factory Girl Trilogy I was very taken with. It’s a story that mixes history and fantasy, and does not encourage you to feel confident about what’s real, and what’s delusion brought on by trauma.

The central character – Tommy – is a massive enigma. The odds seem good that his name is not really Tommy Catkins at all. He’s lied about his age. He doesn’t remember a lot of what happened to him. He doesn’t know if he’s mad, or too afraid to go back to the trenches. He doesn’t know if what he sees in the puddles and river are real, or manifestations from his own broken mind. In some senses he’s an everyboy, all the kids who signed up to fight in the First World War, and who paid with their minds and bodies. There are hints about a personal background, but we’re never allowed to see it, we can only wonder. The story keeps us very much on the outside of his experiences, which of course we are bound to be, because we weren’t there, and we don’t understand.

For me what was most interesting about the story is the way is catches shifts in mental health understanding. Up until the First World War, mental anguish was often treated as a female issue – hysteria – and not taken very seriously. The impact of shell shock on officers and men alike changed public and medical attitudes to the issue of trauma. We went from shooting men for cowardice to taking their broken nerves seriously. The novel explores some of the appalling methods that were attempted as ‘cures’ and the pressure to get sick men back to the front. The idea that mental anguish in face of experience might be the root cause, not a physical reaction, is something the book explores.

This isn’t a comfortable read. It’s a haunting and deeply uneasy book that won’t offer you tidy solutions. If you’re looking for uncomplicated escapism, this isn’t it, but it is a book that can speak in some unsettling ways to that urge for escapism.

July 28, 2018

Calling out abusers

When you call out bad behaviour in others, a number of things may happen. A person who has made an honest mistake, or just been careless, will likely be upset but also sorry and remorseful. Decent people called out on their cock-ups tend to own it and try to deal with it.

Whether you’re responding to something done to you, or calling someone out over what you’ve seen them do to others, the results can be the same, although the consequences of that, in turn, may be different. Here are some of the most obvious outcomes and their implications.

The abuser denies everything. Frustrating if you’re an observer, devastating if you’re a victim. If you’ve been shouted at or hit, and then told that these things did not happen, it’s confusing and distressing. If you endure a lot of it, you may feel you’re going mad. Denying what happened is a form of gaslighting.

The abuser blames the victim. The victim in some way made them do it. Again, this is devastating for the victim, and may over time persuade them that they are responsible. It’s hardest on child victims who have no reason to know it isn’t their fault. If you are not the victim and you get this response, do think carefully about whether the person on the receiving end could really have caused what happened to them. It’s not an argument anyone should be comfortable with. Making victims responsible for the abuse they experience is a form of emotional abuse and gaslighting.

The abuser derides the victim. The victim is crazy, a drama queen, over reacting, a liar, making it up, fantasising, needs help. This is another form of gaslighting that will, over time, cause the victim to doubt their own sanity and judgement. They will complain less, and do less to protect themselves if they are persuaded that their responses are irrational and unreasonable. If the person challenging over abuse is persuaded that the victim is ridiculous, the victim gets less help and support. If everyone is persuaded that the victim is silly and makes a fuss, abuse can go on and nothing is done about it. Do not be complicit in this.

The abuser minimises what was done. A blow becomes ‘just a tap’ a violent shove becomes ‘a little accident’. The abuser says it wasn’t as bad as the victim was making out – again this undermines the victim’s confidence in their own judgement and plays into the idea that the victim is making a fuss about nothing. Watch out for the use of the word ‘just’ in this context. Where the abuse is non-physical, this is even easier to persuade onlookers about. The victim is a snowflake, a drama queen, wants to be the centre of attention, has no sense of perspective, makes mountains out of molehills…

If you have heard about abuse from someone else, rather than seeing it first hand, there is a further thing to take into account when calling someone out: Bullies often play victim. If two people tell you that they are each is being bullied by the other, the odds are that one of them is telling you the truth, and the other is saying it to do more harm to their victim. On the whole, victims tend to be fearful and seeking safety while bullies claiming victimhood are likely to be angry and wanting retribution. Victims may be confused (for all of the above reasons) and not sure if it’s their fault in some way. Bullies are confident when they self identify as victims. The victim is the person most likely to be apologising and wondering how to fix things. If the bully is playing victim and the victim is the person who is saying ‘I think it may be all my fault, I’m afraid I’m a horrible person, I can’t get anything right’ then it can be all too easy to misjudge what’s going on.

Also, if someone is more offended by being called out than they are worried about the harm they may have inadvertently caused, they’re out of order.

July 27, 2018

Heroic Romance

Last week while hanging out with Meredith Debonnaire, we got talking about the lack of pragmatism in love stories. Especially in terms of how this applies to women. I went away and pondered – as I like to do, and a thing struck me.

Western patriarchal societies have not given actual or fictional women much scope in their lives. Mostly, the role of women has been to be prizes to win, or defend, or capture or the harming of women has been a motivation for male characters to do stuff. There are odd exceptions – Lady Macbeth springs to mind, but mostly women in stories aren’t like her. Women in stories are passive. Their job is to be beautiful and to inspire the men to do things, one way or another.

Only when it comes to love are women reliably allowed to do more dramatic things. Women are allowed to die for love, like Juliet. They’re allowed to throw their lives away waiting years to see if the man comes back, like Penelope. They’re allowed to ruin their lives, like Isolde. The can be dramatically murdered by their menfolk, like Desdemona, and so on and so forth. When you look at the dramatic things women are allowed to do for love, it’s clear this doesn’t benefit the women much.

As I was pondering this, it struck me that we have the word ‘heroic’ to indicate the stand out stuff that heroes do. We have heroines, but there is no ‘heroinic’. Heroines just are, it’s not about what they do. If we want to talk about women doing dramatic, brave, important things, it can only be called heroic, because they’re doing guy stuff.

If wrecking your life for love is the only kind of heroism you’re offered, it’s easy to see why women keep telling these kinds of stories, too. But, if you think that taking damage in the name of love is the best and most noble thing you can do, it has consequences. It might make you more willing to put up with violence, jealousy and mistreatment. It might leave you feeling there’s something heroic about standing by your man, no matter what he does. It might encourage you to feel that your worth is defined by what big gestures you can make for the man in your life. It’s a very narrow field to operate in, and it props up ideas about women not having lives separate from the lives of their men.

How many famous historical stories do we have in which women save women? I’ve counted Goblin Market so far. How many historical female heroes do we know of who get to act dramatically and it not be for the sake of a man? There’s Boudicca. There are probably others that I’ve not remembered, but on the whole these kinds of stories are in short supply in terms of the back catalogue. I can think of modern examples, but what we’re steeped in has a very different flavour.

What if we could be pragmatic about love? What if we didn’t tell each other that love is enough and will overcome all obstacles – because life demonstrates routinely that love does not in fact fix everything. What if we don’t celebrate putting your life on hold for a man or sacrificing yourself for a man? What if we stop telling stories that make romantic love the centre of women’s lives and the primary focus for any heroism we might go in for? What if we make it equally ok for male heroism to revolve around sacrifice for love, rather than violent responses to love thwarted?

July 26, 2018

Breaking your social contract

Following on from yesterday’s blog about social contracts, but not requiring you to have read it…

Civilization is, in practice, underpinned by co-operation. There will always be those who try to compete and exploit, and to a degree, that can be coped with. A grouping of people that goes too far into power hunger or exploitation is likely to experience conflict. The laws held by countries, and the rules held by groups of people exist to try and keep everyone co-operative enough for things to work. Crimes are things that have the capacity to undermine your culture.

Any culture, community or civilization has the right to resist behaviours that will undermine its viability. This is not at all the same as having the right to make laws and rules that destroy the freedom of others. There’s only so much rigid control you can inflict on a group before it will shatter under the pressure of that. Those who wish to restrict reasonable freedoms will often justify what they do as being a way of upholding and protecting culture, but that doesn’t make it so. Those who do not want their ‘freedom’ to break social contracts restricted, will call any effort to protect the basis of society an encroachment on their rights.

I think these are the things we need to bear in mind when talking about the right to free speech and the limits of tolerance. If we allow the kind of speech that undermines social bonds we move towards a more oppressive arrangement and if we keep moving that way, we get massive social unrest and violence. If we tolerate people who want to make society intolerable for some, then we’re moving our group towards a state of unviability.

We can afford to accommodate any amount of difference if that difference doesn’t prevent anyone else from quietly getting on with their own lives. Women wearing headscarves are not stopping anyone getting on with their own lives. Women forced to wear headscarves are being prevented from getting on with their own lives. Being LGBT doesn’t stop anyone else from quietly getting on with their own life. If being LGBT is illegal, or encounters violence, then people aren’t being allowed to quietly get on with their own lives.

Tolerance must be limited by whether being tolerant will undermine the feasibility of your people. Tolerance that allows people the maximum freedom it can to live in their own ways, is a good thing. Tolerance that allows people to restrict the freedoms of others is problematic and sows the seeds of its own destruction. The only freedoms we should not allow each other are the freedoms to harm each other. As the intention of hate speech is to bring harmful practices into a culture, hate speech should not be tolerated.

Intolerant societies have violence hardwired into them, and/or break down into violence. Peaceful societies are inclusive, and only restrict freedoms in so far as that’s necessary to prevent harm.

July 25, 2018

Social contracts

Social contracts underpin our lives, but we don’t talk about them much. To participate in civilization and to benefit from it, we have to agree to contribute what we can or at the very least, not go round ruining things for other people. We benefit from all manner of things that belong to, or are funded by everyone – as do private companies, who often use the idea of their private-ness to suggest they shouldn’t have to contribute as much. They use the road networks, the police, the fire services, the education of their employees and so forth.

At the moment, our social contract obliges us to pay for participation with health – when the work demanded of us makes us ill, when the cities we live in have such bad air pollution that it kills people. Participation comes at a high price. I think government and industries alike are failing to hold up their side of the contract, because profit is put before health – especially where air pollution is concerned.

Any practice that allows a few to profit from the natural resources of the world while damaging the environment for everyone else, breaks the unwritten contract. There is no mutual good or benefit here. Why are some people allowed to profit to an obscene degree while others are exploited? Why are some people allowed to accumulate vast wealth at the cost of making others ill? The greater the distance between the richest and the poorest in society, the more strain there is on that unwritten contract that in theory binds us all together.

Poor, vulnerable and under-privileged people who seem to have broken the social contract, are punished for it. Having the resources you need to survive taken from you, being a case in point. That we have food banks feeding people who would otherwise go hungry and even starve, is itself a manifestation of the social contract, upheld by people who believe that we all have a duty to contribute to society and to help those who have less than us. There are a great many individual people trying to hold our social contracts in place despite the way those in power are ripping to shreds that which was never put on paper.

Humans have always depended on co-operation to survive. We all depend on each other. We depend on the people around us to respect us and not assault us. We depend on each other for food, for amenities, for shared resources. And yet all too often we are persuaded to think of ourselves as isolated individuals who can act alone with no consequences. If we don’t see the threads binding us together, we can do massive damage to everything we depend on. If we don’t see the importance of working for the common good, what we get is exploitation, and benefit for the few at a high cost to the many.

When we see society in terms of winners and losers, we make ourselves poorer. Most of us lose. When we see society in terms of co-operation and mutual support, more people are able to win. What would happen if we aspired to make sure that everyone was winning at life? What would happen if we started to see piles of wealth as weird, and offering assistance where needed, as normal? Why not aspire to a world in which everyone has enough and lives peacefully, rather than heading towards a world where a few powerful individuals get to be kings and queens of their own infertile piles of plastic rubbish?