Matador Network's Blog, page 2312

February 21, 2014

Transforming your travel writing pt2

Photo: colink.

This is part 2 of a 5-part series, Transforming your travel writing.

SO OFTEN in travel writing — particularly in travel blogs — there’s a total absence character interaction, as if the narrator operated inside a vacuum. He or she will be in whatever given terrain — a cave in Ireland, a cafe in Buenos Aires, on a river in Western North Carolina — and either there will be no mention of other characters at all, or if there is, they’ll be stripped down to the most mechanical, perfunctory level.

The clumsiest instances of this are when other characters simply show up through some (typically overblown) plot point. For example, halfway through a story about rafting on the Chattooga, a nameless “guide” to whom we’ve had no introduction, no prior description, suddenly appears:

As we dug in and headed toward the biggest rapid, the guide yelled, “All forward!”

Who is this nameless guide? Did he or she suddenly just drop into the raft from space?

Whether writers are cognizant of it or not, this way of describing (or failing to describe) other people can misrepresent how you travel, how you see others, how you interact. Going back to the rafting example: If you were on this trip, would you not ask the guide’s name, try to get to know them at least somewhat, from the very beginning of the trip?

Of course you would.

Likely, you’d be very observant of this person, especially as your safety depended on them. And to take this to another, more emotional level, if you were nervous at all about the experience, you might be dialing in very carefully to any subtle cues they gave off: Did they seem anxious like a rookie? Or were they confident? Did this confidence put you at ease, or did it seem so gung-ho that it alienated you, made you feel inadequate or out of place?

Notice how even thinking about these questions now gets you imagining this “guide” — let’s call her Emma — and what she looks like, where she’s from, how she makes you feel.

Remember that these interactions, these moments meeting “Emma” — or whoever it may be — are what make up your moment-to-moment, day-to-day experience as a traveler. You’re not out there in a vacuum; it’s not all just some depopulated travel “ride.”

Here’s an example: On a recent trip to Oahu, I could’ve just talked about the waves and the hotels and restaurants. But that wasn’t my experience at all. What impacted me — and what I wanted to share about my experience — was the people.

Take this example of how I introduced George Kam:

Sunny [Garcia] taking his place as a mentor, a kind of ambassador of Aloha for the next generation, fit into a long lineage of Hawaiian watermen and waterwomen going back to Duke, and in more recent times Eddie Aikau, Gerry Lopez, and others whose connection to the water was so pure and inspiring that they became teachers and guardians for others.

Thus, I felt extremely humbled (and slightly nervous) when, a couple days later, I was to meet Quiksilver’s Ambassador of Aloha, George Kam. George was in his early 50s and had a buoyant, warm demeanor, smiling as if you were one of his long lost cousins.

“Just tell me what you feel like doing today,” I said. “I’m down for whatever.”

“First thing we need to do is get you outfitted,” he said, laughing at my paint-splattered, worn out Hurley trunks. “We can’t have you going out there looking like that.”

Notice how the narrator’s “introduction” of George Kam accomplishes several things:

It gives context, explaining how George fits into a certain tradition within Hawaiian culture as well as his current work / “role.”

It expresses emotion, giving a sense of the narrator’s respect and even feelings of intimidation (which will later set up the opportunity for ‘demystifying’ the character through their interactions).

It gives physical details that register on an emotional level: “buoyant, warm demeanor, smiling as if you were one of his long lost cousins.”

It’s built around interaction and dialogue, not just telling how the character is, but portraying them through an exchange.

In the next article in this series, we’ll look at more ways to develop these points. For now, ask yourself: Is the narrator in your travel stories operating in a vacuum? How are you portraying other characters? [image error]

Editor’s note: This lesson is excerpted from new and forthcoming curricula at MatadorU’s Travel Writing program.

The post Transforming your travel writing, pt. 2: You’re not in a vacuum appeared first on Matador Network.

The truth about our eco choices

THERE ARE some staggering statistics mentioned in this TED talk by Leyla Acaroglu, a social scientist-slash-product designer-slash-sustainability strategist. Stats like:

40% of fresh food is wasted in the US, which equates to $165 billion per year.

Methane, which landfills emit, is 25 times a more potent greenhouse gas then CO2, meaning how you dispose of waste, whether or not it’s biodegradable, is very important (in other words, simply choosing the biodegradable option doesn’t automatically mean you’re a saint).

65% of Brits (a country in which 97% own electric kettles) overfill their kettles, wasting a lot of energy. This wasted energy, from one day and just from kettles, is enough to light all of the streetlights in England for a night.

It’s cheaper to mine gold from e-waste than it is to get it from ore (a terrible health and eco problem in many countries around the world where people burn toxic material to extract it).

In the end, she says consumption is the biggest problem — which is obvious — but given it’s the lifestyle the vast majority of people in our culture abide by that’s not likely to change anytime soon. So instead the solution is to be innovative with product design to lessen the impact on the environment, like designing kettles that make it possible to boil just a cup of water, or fridges that don’t promote the wasting away of fresh food.

The post The truth about the environmental choices we make [vid] appeared first on Matador Network.

7 reasons to avoid the Tiger Temple

Photo: Avatarmin

Wat Pha Luang Ta Bua — better known among travelers as “Tiger Temple” — is probably the most controversial temple in Southeast Asia. You’ve probably seen pictures of people posing next to a majestic tiger, bravely holding up a tiger’s tail and grinning proudly, or perhaps even shoving a baby bottle filled with formula down a tiger cub’s mouth. Obviously great shots for Facebook.

However, I’m here to tell you those photos come at a steep price. In August of 2013, I volunteered to work at Tiger Temple for 30 days. I left after 18. Here’s why.

1. Tiger cubs are taken from their mother and given to tourists at two weeks old.

Two weeks into this world, and a mother has her babies taken from her and handed over to the tourist hordes for bottle feeding and nonstop molestation. Tigers are solitary animals in the wild, but they stay with their mother until about the age of two. Two years, not two weeks.

2. Cubs are bottle-fed daily — over, and over, and over…

Keeping an animal well-fed is a good thing; having an animal fed by tourists all day long until formula is spewing out its mouth is not.

The temple makes the most money from everything cub related, so a long morning program with four afternoon feedings / tourist molestings is normal.

3. Tigers, tigers, tigers everywhere, but where are the rest?

When I volunteered at Tiger Temple, there were two 2-week-olds, three 6-week-olds, and three 16-week-olds. As I mentioned above, the temple needs babies, lots of them, because they are the cash cow of Tiger Temple. However, assuming a normal birth rate, the temple should have way more than 122 tigers under its care. Where did the rest of the tigers go? (Hint: Many neighboring countries believe tiger parts have magical medicinal powers.)

4. Tigers need exercise, but few actually get to at Tiger Temple.

I don’t know about you, but when I don’t exercise I tend to get fat, lazy, and upset. Now imagine a tiger whose basic existence depends on exercise.

Oddly enough, many critics of the temple point to pictures of tourists with sticks with bags on them playing with the tigers as “tiger abuse” — teasing. However, this “playing” is good for the tigers — it provides exercise and mental stimulation that they desperately need. The problem is only around 20 of the tigers actually get to exercise like this daily. The rest are stuck in a cage — sometimes six big cats in one cage.

5. There’s an inherent danger to being too close to unpredictable wild animals.

Photo: Author

Every year like clockwork, a tiger mauls an unsuspecting tourist. Even if the tigers are chained down like prisoners to the ground, even if the tigers are raised by humans from birth (see: stripped from their mother), there will always exist the possibility of an animal lashing out.

And when a tiger lashes out, it’s not a house cat lashing out — it’s a 400-pound animal acting instinctively. It hurts. Ask this girl.

6. The tigers are on the equivalent of an American diet.

The animals are fed boiled chicken every day. Many are overweight and have underdeveloped muscles. Tigers need to eat red meat regularly to get the enzyme taurine and other essential vitamins for their muscle development and long-term health.

Tiger Temple claims they can’t give the tigers red meat because it’s “too expensive.” Too expensive? I guess the temple isn’t making much money…

7. The money tourists “donate” doesn’t go to tiger conservation, or anything remotely related to it.

Tiger Temple is a Tiger Business. And a shady one at that. The money tourists give goes first and foremost into building this big Vatican-like Buddhist temple out front. The “tourist donations” don’t help tigers in the wild, and if anything, falsely lead people into thinking they’re helping wild tiger conservation.

Likewise, how can the temple claim red meat is “too expensive” to give the tigers, while turning a phat profit and building a big-ass temple out front? Just because a place is run by a bunch of “monks” doesn’t make it holy (see: monk who runs with $32 million).

* * *

We vote with our tourism dollars, so next time you visit Thailand, instead of photo-opping with chained-up tigers, why not get up close and personal by volunteering with some rescued elephants? The tigers will thank you for it, and so will the elephants. [image error]

The post 7 reasons to think twice before visiting Thailand’s “Tiger Temple” appeared first on Matador Network.

February 20, 2014

I was robbed in Sicily

Photo: i k o

I was recently beaten and robbed in Catania, Sicily.

The highlights included being thrown to the ground by six young Italians who couldn’t manage to kick or punch through my grip on my bag; my wife having her camera bag, a recent Christmas / birthday / graduation / Valentine’s present, ripped off her shoulder; her screaming “Polizia! Polizia!” and her brief but courageous pursuit as our assailants fled; two futile visits to the police, where we learned that most young male delinquents in Catania have protruding ears, which may be significant but not to this story; and the ensuing period of resisting the urge to paint broad strokes of judgment all over Sicily, which would be a even larger injustice than the mugging. Aside from one chunk of ground in Catania, I highly recommend visiting the island.

I’m still puzzled by those three minutes. Aside from the first blow, I don’t remember any physical pain. The strongest memory I retain is the feeling of disbelief towards the events as they unfolded. That something could be taken from me (or, more accurately, something could be taken from my wife and from us) felt so unreal. This thought, along with muscles strengthened by years of playing guitar, may be why I simply refused to let go of my bag. But what did give way under those kicks and punches was my grip on my self-narrative.

We travel and we take. This is true for most travelers. Confession: I enjoy taking, but not as much as I used to. I still like how my thumb magically causes cars to stop, and I still enjoy those warm beds strangers offer me. (Couchsurfing? More like “Here’s the keys to my apartment,” or, “Let me show you around the city, feed you, and give you this nice bed” -surfing.) But the focus changed as I slowly realized these were opportunities to share a piece of life with others. I felt I had reached a place where responding with hospitality isn’t an obligation but a reflex and an opportunity…and then I was beaten and robbed and confused in Catania, Sicily.

I felt the change the next day when we returned to the scene of the crime. The daylight gave the nondescript street innocence. Mothers were hanging laundry and old ladies were returning from grocery shopping, plaid rolling bags in tow. But to me, everything and everyone seemed guilty. Each car that passed was for a split-second the blue getaway car our assailants piled into. I felt fear as teenagers zipped by on mopeds. Unable to shake the role of victim, accusation became a salve for helplessness, and I had to fight the urge to view everyone as a potential threat.

The store we had stumbled into the previous night was closed. The shop owners had refused to call the police or help at all. Their eyes had been full of fear and complacency. To some extent I empathize with them, but only because a few times in life that come to mind when I didn’t help those who needed it. That time I was walking to my apartment in Prague and saw a man beating his wife. Or that time in the Republic of Georgia when my co-teacher’s drunken husband kidnapped her at knifepoint in the middle of a 10th-grade English lesson.

I don’t excuse the shopkeepers — or myself.

I still feel helpless when I tell this story. Retelling it is easy, almost boring. It happened, it’s part of my life, but I still don’t understand it. I’m still waiting for the, “And the moral of the story is…” moment, if it ever comes.

I can’t think of a feeling worse than helplessness towards the past. I’ve chewed over the whole Catania business countless times, and I still don’t know how to approach its memory. But I am rebuilding trust — night is less dark, long walks are regaining their status as God’s gift to mankind, and strangers are less strange. I have to. If I don’t continue using travel as a means to live better in this world full of humans, then a lot more was taken than just a camera. [image error]

The post That awful 3 minutes when I was robbed in Sicily appeared first on Matador Network.

Brutal video of Ukraine protests

THIS VIDEO was published today by euronews. According to their reports, the death toll is in the dozens, with claims of up to and over 70.

The post Graphic video footage shows brutality of Ukrainian protests appeared first on Matador Network.

10 embarrassing American stereotypes

Photo: Keoni Cabral

1. We’re FAT.

If there’s anywhere to start, it’s right here. Our expanding waistlines have been the subject of global ridicule for decades, with our weapons of mass consumption fed with bottomless obesity fuel, and our luxurious domestic throne rooms of TV appreciation and ever-present automobile infrastructure at the ready to remove any and all semblance of physical activity from our daily routine.

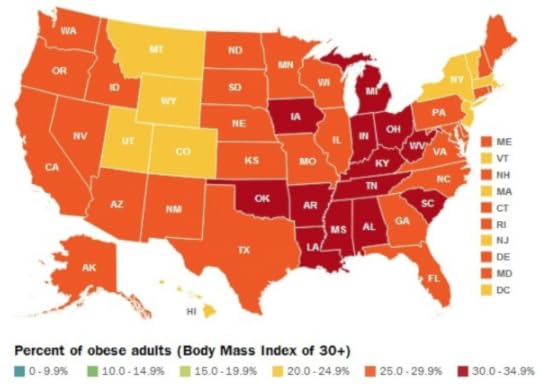

A couple fun facts: 68% of Americans were overweight or obese in 2012, and since 1960, we’ve packed on an extra 24 pounds each, causing endless problems related to diabetes, heart disease, fuel consumption, and airplane seating size standardization. Somehow that $60 billion we spend every year on weight loss products is getting us nowhere.

2012 obesity rates, state by state. Not overweight…obese. Deep red is over 30%. Source.

When I was in Taiwan, one of many nations for whom portion control and lack of trans fats are simply non-issues, I was asked if I thought the humans in Wall-E were a realistic portent of our inevitable fate.

They thought it was silly to think humans would end up as severely fat, immobilized, and digitally entertained as the characters depicted in the film…whereupon I informed them that a certain percentage of our population has already achieved such a feat.

Asia in general has significantly lower rates of obesity. Just for a quick comparison, our 33.8% obesity rate is pretty darn easily beaten by Japan’s 3.5%. Get it together, America.

Minor consolation? Someone overtook us. But our current 2nd place fat trophy is no reason to cheer. And I expect our size and sedentary vegetating often contribute to another particular sort of laziness…

2. We barely travel.

We’ve all heard the embarrassingly low statistics concerning the percentage of Americans holding passports, but at this point, it’s over 30%. Still incredibly lame, and far behind the UK’s 80%, but a lot better than you may have heard.

But I think that misses the point. It doesn’t matter how many people have passports, but how many use them. And according to a (somewhat outdated) study that ranked countries according to number of trips abroad, the USA is in a respectable 3rd place. Woo hoo!

Passport ownership, state by state. Source.

But that’s by sheer numbers, not per capita. Germany was #1, with 86.6 million trips abroad…compared to a population of 80 million.

Compare that to the 58 million trips Americans took abroad, and our 300 million people, and Germans turn out to be quintuple the travelers we are.

We’ve got all sorts of excuses, of course. We live far away. Our economy sucks. And we barely speak our own language, much less others.

And all that would make sense, except when you take a look at Canada, where a respectable 60% hold passports, and according to tourist receipt data from 2009, they spent about 1/3 as much as (USA) Americans did on travel, but with only 1/10 the population, which makes them approximately triple the travel junkies we are. And both are in North America, so I don’t think problems like expensive plane tickets are good enough excuses.

A frequent argument put forth is that travel expenditures correlate closely with income and proximity to international borders, and that’s true enough, except when our Canadian buddies are upstaging us 3 to 1. I mean seriously, guys. Who the hell doesn’t want to see the world?!?!!

And you might think travel is a frivolous expenditure that doesn’t count as a necessity of life. Except that it exacerbates the next problem…

3. We’re ignorant of the world.

I won’t trot out the parade of ignorant Americans saying silly things about whether Europe is a country or Africa is a planet or whatever. I’m sure you’ve seen ‘em. And this is to say nothing of the Americans who don’t know the Earth goes around the sun.

What bothers me far more than mere stupidity is the cultural prejudice that festers from this ignorance, and keeps millions of Americans irreparably distrustful of the outside world. We’re constantly in fear of a rising China or resurgent Soviet empire or socialist European dictatorship or reincarnated Caliphate, or whatever the hate target is for that particular decade. You can tell which racial group is the big bad wolf at the time because they’re the bad guys in all the movies. Hollywood is literally chronicling our xenophobia before our very eyes.

Quick, fill in every country you can!

I wish I could find the source, but several years ago, a few Muslims went on a cultural exchange tour, intended to increase communication and understanding between Christians and Muslims, at a time when the media continues to push some of us into thinking we’re destined for some inevitable clash of civilizations. And Christian attendants actually asked, “Do Muslims love their children?”

The price for such ignorance? Unchecked ease of political manipulation. While knowledge remains a magnificent way to spot a liar, it remains childishly easy to manipulate an ignorant voting bloc, which is a big reason why Americans need to travel more. We’d know the whole rest of the modern world does healthcare better, or that Amsterdam isn’t a cesspool of drug-addled violence, or that public transportation systems don’t have to suck. But too few venture beyond our borders, which is why the last two elections saw candidates for some of the highest offices in the land claiming on TV that Russia is still our arch-nemesis, and almost half the country voted for them.

Ignorance happens everywhere, sure. But in a country so well-connected with the outside world, and with a communications infrastructure that allows us to consume seemingly any cultural creation the world can produce, ignorance is not an accident. It’s a choice. And many of us make it every day.

4. We’re scientifically illiterate.

The country that flew to the moon still has 20 million people that believe it was faked. A few fun facts about American scientific flailing:

34% of Americans believe in ghosts.

18% still believe the Sun goes around the Earth.

32% think stem cell research is morally wrong, but only 20% actually know what stem cells are.

Sigh. And it can only become increasingly problematic to maintain this level of ignorance. At no point in our future will scientific literacy become less important. The more we invent and discover, the more we’ll need to know what the hell is going on. If we haven’t even caught up with the discoveries of Copernicus, how can we be expected to handle all those flying cars we’ve always wanted?

But we might not be able to afford them anyway…

5. We’re rich…ish.

Some of us, anyway. Income inequality has become a hot-button political issue lately, and for good reason. The chasm between rich and poor has grown to match the level of the Gilded Age of the 1920s, right before the most horrific economic collapse in our history. The super-rich of the 0.01% control a greater share of wealth than at any time in recorded history, while their taxes are among the lowest they’ve been in our lifetime, which all adds up to make American income inequality the most severe of any developed country.

Now you might think that’s fine, since they must have worked hard for all that wealth, right? Well, not those six Walmart heirs, who control as much wealth as the bottom 40% of Americans, and certainly not in the case of all those politically derived tax breaks and offshore bank accounts that allow rich people to build massive amounts of wealth while selling out their own country at the same time. But even aside from all that (which I think is pretty awful to begin with), there’s a direct correlation between income inequality and everything bad in the world.

For many years, we grew together. But for several decades, we’ve grown apart. And it’s breaking the country in half. Source.

It would be one thing if they were working hard and reaping deserved rewards, but when plenty of other people are working hard but not even managing to break out of poverty-level wages, something’s gotta give.

And I think it should be rich-people tax evasion scams, not child-poverty nutrition programs.

And, for those who think billionaires paying an extra tax percentage or two will cause our democracy to collapse into a socialist dictatorship, it’s probably worth knowing that when our country was fighting World War II, tax rates on the top earners reached 94%. Is it really so much to ask our new nobility to contribute to their country in a time of need?

Yet such modest suggestions are met with fervent, ideological, almost religious opposition. Speaking of which…

6. Religious fanaticism runs deep.

Now allow me to begin by pointing out that I have no problem with people practicing their religion. I strongly support absolute freedom thereof. Unfortunately, a third of Americans do not. We’ve reached the point that 34% of Americans would favor the establishment of Christianity as the state religion.

It’s funny how vocal the debate can get over whether or not the United States was founded as a Christian nation, since the Treaty of Tripoli literally declares the exact opposite and bears the signature of President John Adams. Seems like it would be over and done with, right?

Nope. The debate rages on. And although religious participation is generally down, with increasing numbers of Americans (particular younger ones) declaring no religious affiliation at all, the number of Americans claiming that “Christianity is a very important part of being American” increased from 38% to 49% from 1996 to 2004.

So while it’s not entirely accurate to call the United States “religious,” it’s perfectly accurate to claim this for half the country, whose opinions have become so deeply entrenched that a third of Americans apparently want to see the country transformed into a Christian theocracy. We’re getting split right down the middle, and religion is the wedge. One of them, anyway.

Good thing all that religious fervor must be keeping everybody morally righteous though, right? RIGHT!?!?

7. We have more prisoners than anyone else.

I find it rather odd that Americans talk about Americans like we’re the greatest people on the planet, while simultaneously locking up the highest percentage of our citizens of any country on the planet. How great can we be if we have more criminals than anywhere else?

Know what happened at the time of the spike? Privatization. Chart by Pwrm.

Yet for many Americans, this isn’t even a problem. They view record-setting incarceration rates, mandatory minimum sentencing, zero-tolerance drug offense policies, and the $75 billion annual tab as the solution, failing to see how these astronomical imprisonment rates only serve to exacerbate the existing problem.

We turn non-violent offenders into inmates, whose criminal record then guarantees employment challenges. And what’s a former criminal to do when the clean life won’t pay the bills? Turn to crime, of course. And so the term “correctional facility” is just a lie: Within three years of release, about 43% of inmates end up back in prison.

You might think those repeat offenders deserve it, but in Norway, it’s just 20%. So it’s not just the offenders that get themselves back into the system. It’s equally a result of the system itself.

And thus we could save billions, while drastically cutting crime rates at the same time, but instead we’re just spinning along on our imprisonment hamster wheel, all the while suffering, and paying for, the enormous consequences. Such as…

8. Our gun crime is out of control.

There’s no modern country on the planet that has the same problems with gun violence as the United States. In 2006, over 10,000 Americans died gun-related deaths. In Japan? Two.

Number of guns per 100 people. We’re in red.Source.

Sadly, it’s not just murder. Gun-related suicides actually happen more often than gun-related homicides. In 2010, the ratio was 1.75 to 1.

I’m all for allowing gun ownership for the sake of self defense, but when most of those deaths are self-inflicted, it’s really not a matter of defense, is it?

The cycle is depressingly self-defeating; every school shooting leaves the public terrified, and clamoring for reasonable gun control legislation. Fearing tyrannical regulation, gun lovers flood the gun shops and stock up on new firearms. And since the gun lobby blocks even the most reasonable of new regulations, no progress is made…except for the massive addition of newly circulating firearms, thus enabling yet more school shootings.

And Americans think other countries are dangerous.

9. Our military budget is killing us.

Speaking of massive stockpiles of deadly weaponry, the United States consistently outspends everyone else on the planet on our military, exceeding, as of 2013, the next 11 countries combined. It would be one thing if we were at war with all of them simultaneously, but plenty of them are allies. Awesome.

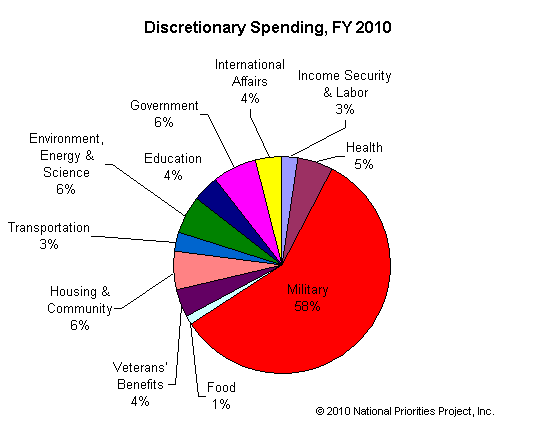

More fun facts? The United States accounts for about 40% of global military expenditures, spending about 6-7 times as much as China, the next biggest spender. And although the Department of Defense has accounted for about 20% of the federal budget for the last several years, other estimates, which include defense-related spending beyond simply the Department of Defense, put the number at a staggering 58%.

This is the budget of a country at war, not a country fighting a few insurgent forces in 3rd world countries.

Even so, no discussion of reining in government spending ever includes a reduction of military might. One might think it would be simple to suggest we outspend the next eight countries combined, instead of the next eleven, for example.

But it’s just so easy to say “weakening America,” “grave threat of terrorism,” and “support our troops,” that no politician seems capable of mustering the intellectual prowess to ask, “Could more lives be saved if we spend those billions elsewhere?”

And while I have nothing but respect for the soldiers who put their lives on the line for the sake of their country, I have nothing but disdain for the politicians who put soldiers’ lives on the line for the sake of their political career. And judging from the vast number of third-world countries we’ve invaded or bombed that pose absolutely no threat to us whatsoever, we seem to have quite a few of them.

The trouble is perhaps best phrased by Abraham Maslow, who once said: “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

So we keep on banging away.

10. We don’t know what “patriotism” is.

This is a big one for me, as it tends to eclipse any other problem, by facilitating the existence of them all.

I’ve written before about the mentality of certain Americans who think it’s “very special” to be American, but whose only explanations consist of factors present in hundreds of countries. Democracy, for example, or freedom of speech. Or people who refuse to travel to other countries for fear of their safety, including those with significantly lower crime rates, or who believe American citizenship somehow entitles them to the favorable economic circumstances our country currently enjoys.

Well said, George.

And though it would be one thing for sheltered Americans to continue ignorantly wallowing in the mediocrity that is the current chapter in the history of the United States, it’s another thing entirely when that ego merges with assumed privilege.

A disturbingly popular view has emerged in recent years, which declares that the United States has a unique privilege in the world, which allows it to pursue whichever goal it desires, without regard to its effect on citizens of other countries. All because America is the “greatest country in the world.”

I once witnessed an American pack up his things and refuse to speak further with a Swiss man who (politely) suggested the United States should take into consideration how its actions affect the populations of other countries. And when the Swiss man left the room, the American said, “I don’t like that guy.” For the crime of suggesting considerate behavior.

And this is no fringe view. When a recent political candidate recommended following a foreign policy based on the Golden Rule, the audience shouted him down. This country literally witnessed the voters and leadership of a major political party revolting against the basic concept of morality.

If you ask me, greatness doesn’t provide leeway for inconsiderate behavior. In fact, it does the exact opposite. No one has ever seriously declared, “He’s a great person, so he can bomb other people.” And yet somehow it’s perfectly acceptable — to certain people, anyway — to provide this privilege to an entire country.

That isn’t patriotism. It’s narcissism, plain and simple. And it’s blinding us from recognizing or solving the massive challenges we currently face. [image error]

This post was originally published at Snarky Nomad and is reprinted here with permission.

The post The 10 most embarrassing American stereotypes (that are kinda true) appeared first on Matador Network.

The Pale Blue Dot

Carl Sagan’s famous “Pale Blue Dot” speech, from his book of the same name, are possibly among the most profound words ever strung together at once. This animation of it, by Adam Winnik, is literally my favorite thing on the internet. Sagan was an astronomer best known for his TV show Cosmos (which is about to be resurrected by Seth McFarlane and Neil deGrasse Tyson). He sadly died back in 1996, before I had even heard of him.

I saw this video a couple years back when it was first made, during a particularly rough mid-twenties-existential-crisis, and it managed to pull me out of it. The speech — about the insignificance of mankind in the grand scheme of things, and the silliness of how badly we treat people considering — should be watched and taken to heart by everyone. Hopefully it makes as much of a difference for you as it did for me. [image error]

The post The Pale Blue Dot: This 4-minute animation could literally change your life appeared first on Matador Network.

What it took to get this photograph

Photo: author

This is a photograph I snapped near the top of a Himalayan pass traversing the Parvati-Pin valleys in northern India, on my first travels to the country in 2009. The altitude of this crossing was a pretty humble 15,000 feet.

I worked as a porter for a French trekking guide based in the village of Vashisht, Manali, Himachal Pradesh, and was paid 200 rupees ($4) per day to carry about 45 kilos (90-some pounds) of equipment, including kerosene stoves and camping gear, to serve a group of four Canadian tourists. We trekked 10 days, crossing from a temperate mountain region into a very dry and desolate area where many Tibetan refugees have made their homes. It was much like crossing the Cascades on foot, only to be met by even more enormous mountains on the other side.

I cooked for four people at the end each day. Really nice meals. I only ate rice and lentils with my Nepalese friends who had been hired as porters for this trek and invited me as a 10th member of the laboring team to haul supplies. That was their difficult livelihood — working for a couple dollars a day to carry the supplies that provided for the recreation of guests who paid over $500 to temporarily enjoy themselves and the scenery. The profits mostly went to the trek guide, a French woman who didn’t do anything but walk straight ahead and bark out orders at the beginning and end of each day. Her passion for pushing everyone enabled all of us to be the first to cross the pass that year.

The experience, only 10 days, was the most difficult I have ever embarked on in my life. It was driven by a kind of empathetic need to identify with the Nepalese laborers I sat with every day in the village. I wanted to understand their perspective of life as migrants living away from their homes and families. The Indian rupee is strong to the Nepali rupee, like the dollar is strong compared to the peso, inviting foreigners to come across the border to work and send the earnings back home to their villages.

I would be paid and treated just as if I were a Nepali man. Same pay, same food, same tent.

I originally wanted to just sport a pair of the straps I saw them use to haul loads up and down the village, but was told it was no job for me. I kept insisting — sitting with them each morning drinking chai and smoking bidis — and studied as much Hindi as I could cram in order to communicate deeper and deeper thoughts to them. Eventually, I moved in with a couple Nepali fellows. They were sharing a small living area in Dhungri village. I call it a living area because there was no kitchen, no bathroom, no electricity. It was just a stone-walled room where blankets were spread along the floor and men slept against one another like matchsticks. The kerosene stove would be lit and the whole room would fill with smoke before getting hot enough to put the bowl of rice down onto.

I guess in first-world terms, I was smack dab in the middle of “developing-nation” poverty. Whatever that means. I didn’t actively notice that about them, though, and they didn’t seem to notice that I was any different from them. Their humble nature drew me to them. Their happiness despite their conditions of living. Their invisibility as hard-working people amidst a foreign, predominant culture in an overrun tourist haven. They decided to take care of me. I became their student. It reminds me of the quote from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath:

If you’re in trouble or hurt or need — go to poor people. They’re the only ones that’ll help — the only ones.

A few days after I began living with these men, one of their cousins, living in the village a few kilometers down the road, came over and heard about my quest. He was a Nepali man that could speak a little bit of English. We spoke in two languages to communicate any single idea. It was an awesome, patient process. He told me that a trekking party would be going out in a few days and invited me to work with them as a “coolie” — a porter. He told me what the journey would entail — 10 days of arduous trekking over an unfathomably rugged but scenic landscape — and that I would be paid and treated just as if I were a Nepali man. Same pay, same food, same tent.

I got my stuff together and prepared to embark into the tallest mountains in the world.

Upon leaving, I was quickly humbled. Carrying this much weight as a person who was only 19 years old at this point over such a long distance quickly felt impossible. Every step forward up the steep terrain was a very conscious process. I was totally unprepared for how daunting these mountains were. I was tall and lanky — the Nepali were short and stout. Built for the mountains.

I came to notice quickly how certain privileges operated in society. After all, the end of the day brought rest to the well-funded tourists who were seeking a challenge for the fun of it. For me, my responsibility after a long day of hauling gear entailed setting the tourists’ tents up for them, cooking their delicious meals, and then cleaning up before going to bed. There was never a moment to rest for me, or for the Nepalese men who labored unflinchingly in their service the entire trip. At night, each of the guests would sleep comfortably in their own tent that we carried for them. I would go to the one tent that housed all 10 of us laborers to eat a plain dish of rice and spiced lentils before sleeping.

I still had a definite privilege, of course. I had signed up and volunteered for suffering. I did not have to make $4 a day to survive.

Still, I really started to identify with the Nepali workers, especially when the guide started to treat me like I was something lower than a paying customer…something like “them.” I felt sorry for how much they had to sacrifice and endure while others were able to live with so much pleasure and comfort, only because they had more paper in their pockets. I questioned them about their living conditions, their families, their children, their way of life. I quickly started to resent the guests. The whole day they were well ahead of us on their own private tour, while the rest of us lagged behind carrying the gravity of their luggage. It was a humiliating experience. An experience that these men had to go through year after year after year, without ever getting to know those whom they served.

I thought I was going to die. Probably the first time I had intimately felt that impending doom dawn upon me.

The worst moments were toward the end of the trip, crossing a glacier. The guide had packed snowshoes and safety equipment for the paying customers only. The Nepalese men, being poor, and I, being foolish, had come all this way to the top of the Himalayan range either wearing chappals — sandals — or rubber mukluks. At this point, one slip on the glacier would send one careening off the face of the mountain, in some places thousands of feet down to the valley floor. I thought I was going to die. Probably the first time I had intimately felt that impending doom dawn upon me. No way to say goodbye to family or anybody up there.

The photo at the top of this article is actually just after I made it to a safe place where I no longer felt endangered. A kind of, “Thank you. I am going to remember everything this trip has taught me forever” moment. I remember at this moment — a boy no older than I — started to cry because of the pressure that had been put on us all to make this happen, the first ones crossing the pass that season. It was dangerous, and without the proper equipment the top was especially precarious. Often, step after step, we would break through the snow and ice, with a 100 pounds on our backs, and be stuck up to our necks unable to get out without assistance. It was frustrating and exhausting. We were all running, literally, on will.

I shook with weakness. It took every last breath out of me and every last tear out of another. A strong kid, no less. Of course, none of this was witnessed by those who were comparably amongst the wealthiest young travelers on this planet. A microcosm of the world we live in. Suffering, exploitation, and violence gets outsourced, silenced, and hidden so civilized society can continue to live unabated in fantasy-land. “What a marvelous trip!” they would exclaim.

No less, the view from the top of the world, seeing into central Asia and Tibet, was one of the most majestic sights and beautiful feelings I have ever had. We had done it together and only with each others’ encouragement and help. We smoked a few bidis before descending into Spiti Valley. But before I left I stood there hugging those men under the prayer flags. [image error]

The post What it took to get this photograph appeared first on Matador Network.

New Pussy Riot protest video

JUST LAST December, two members of Pussy Riot — a Russian feminist punk rock group — were released after being held in prison for almost two years. They were convicted of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” after the group did a performance in a Russian Orthodox Church (the sentence was considered a human rights violation by many international organizations). They claim they were protesting the church leader’s support for Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Yesterday the band was beaten by cossacks — who were historically responsible for patrolling borderlands, and are today used as security at the Sochi Olympics — while they performed their protest song “Putin will teach you how to love the motherland.” They were then temporarily detained before being released.

Today they’ve released their music video which contains footage of the brutality. Translated lyrics for the song are below.

$50 billion and a rainbow ray

Rodnina and Kabayeva will pass you the torch

They’ll teach you to submit and cry in the camps

Fireworks for the bosses. Hail, Duce!

Sochi is blocked, Olympus is under surveillance

Special forces, weapons, crowds of cops

FSB – argument, Interior Ministry – Argument

On [state-owned] Channel 1 – applause.

Putin will teach you to love the Motherland.

In Russia, the spring can come suddenly

Greetings to the Messiah in the form of a volley from

Aurora, the prosecutor is determined to be rude

He needs resistance, not pretty eyes

A bird cage for protest, vodka, nesting doll

Jail for the Bolotnaya [activists], drinks, caviar

The Constitution is in a noose, [environmental activist] Vitishko is in jail

Stability, food packets, fence, watch tower

Putin will teach you to love the Motherland

They will turn off Dozhd’s broadcast

The gay parade has been sent to the outhouse

A two-point bathroom is the priority

The verdict for Russia is jail for six years

Putin will teach you to love the Motherland

Motherland

Motherland

Motherland

To read more on the story, click here.

The post New Pussy Riot music video includes footage of beatings appeared first on Matador Network.

5 unspoiled European beach towns

Skagen, Denmark. Photo: ViktorDobai

I love the South of France just as much as the next person. Yet, sometimes the Promenade des Anglais feels more like a crowded Miami boardwalk than the beach-y slice of picturesque romance it’s supposed to be.

The usual beach destinations — Mykonos, Sardinia, Cannes, Ibiza, etc. — are fine, but if you’re looking to escape the scenesters, perhaps sip a glass of wine that costs the equivalent of 50 cents, and soak yourself with warm water and rays in entirely unique destinations, you might check out one of Europe’s least-touched beaches. From the Albanian Coast to little-known French islands, have a look at the beaches that will give you both bragging rights and some well deserved relaxation from all the usual beach-going fuss.

1. Himarë, Albania

It’s only about 50 miles east of Italy, but the beaches of Albania that sit on the Adriatic Sea could not be more different from the Italian Riviera. Beachfront hotels for $50, easy access to postcard-worthy ancient ruins like Butrint and Himarë Castle, gorgeous beaches (try Gjipe or Jali), and laid-back locals make the Albanian Coast good to go. Plus, it’s weird. Thanks to its Communist years, in some areas Cold War-era bunkers dot the coast, barely held up by the white sand.

The easiest way to get to Himarë is to fly into Athens, then take a short bus to Vlorë or to Himarë, where you can dive right into the blue Ionian Sea — not a soul in sight.

2. Vama Veche, Romania

Not the type of beach where you tan all day and head out clubbing all night, Vama Veche is more the communal “let’s camp and sing around the campfire” type of place. It’s a small village near the Black Sea, with a beach that’s like a subdued Burning Man, playing host to all sorts of fascinating people who bring along guitars, sleep in tents, and awake to the gentle sound of breaking waves in the morning.

It’s free to camp, but do be a little careful — there’s a nudist section of the beach, which, while discreet and well nestled away, might not be a pretty sight to wake up to.

3. Skagen, Denmark

Denmark is known for its philosophers, writers, physicists, filmmakers, even as Hamlet’s kingdom — few think of untouched beaches. But head to Skagen — once a hotspot for painters thanks to its clear, bright light — and you’ll find not only art museums but also massive white sand dunes.

Sometimes known as ‘The Scaw,’ this northernmost peninsula is in a constant state of flux, as the sand dunes are perpetually created and destroyed by the strong night tide. Somehow, though, little has changed in this Scandinavian city since it was founded in 1413. Seeing as the population is only about 8,000 people, take a flight into Denmark’s second-largest city, Aarhus, and enjoy the short bus ride to Skagen.

4. Piran, Slovenia

I first stumbled on Piran, a tiny town on the tip of Slovenia surrounded by the Adriatic Sea, from a few gorgeously colorful pictures of the city center I’d found on Instagram. Get here and you’ll be spending your whole day in the water (either in Piran, or take a short bus to the more spacious beaches in Isola) and eating at one of the restaurants on Tartini Square, where you can get a wonderful glass of Slovenian white wine and freshly caught seafood for practically nothing.

To really escape the crowds, navigate the cobblestone streets to the top of the city and its 7th-century castle. At the top of the stairs, there’s a panoramic view of the peninsula, the Adriatic, and the sparkling lights of Croatia in the distance.

5. Noirmoutier, France

It would be wrong to regard all French beaches as touristy and expensive. Linked to the mainland by a pair of bridges, the island of Noirmoutier is full of rugged, grassy terrain complete with Quixote-esque windmills and quiet boardwalks.

Yet what makes the island truly one of the best secret beach destinations is its French-infused Mediterranean vibe and a full 25 miles of sandy beaches. Make your way through the Boise de la Chaize — a small forest of oak trees and eucalypti — which opens up to the Plage des Dames. Here you’ll find soft sand, turquoise water, cozy beach huts, and, perhaps most importantly, not a hotel in sight. [image error]

The post 5 unspoiled European beach towns you’ve never heard of appeared first on Matador Network.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers