Matador Network's Blog, page 2293

March 28, 2014

Navigating stuckness

Getting stuck – at New York’s Lincoln Center fountain, with an approximate timeline of my life. All images by author.

Getting stuck

A few weeks ago, I was having dinner with my mom in Manhattan. She was telling me her plans for this year’s Christmas card. “This year,” she said, “instead of writing my usual newsy card, I think I’ll just say, ‘Amanda’s about to have a baby, and Jonathan moved from California back to New York.’”

“Sounds good to me,” I said.

“Well,” she said, “it seems like you used to do so much in a year, and I always wanted to include all your news. But this year, it just seems like you haven’t been doing very much, so I figured a shorter note was in order.”

I squirmed in my chair and readjusted my napkin. My mom — maybe like all moms — has a special way of saying just the thing that’ll hit your most vulnerable spot. She’s right — this year, I haven’t been doing very much. I’ve spent a lot of time wandering into churches, reading old journals, watching YouTube videos, and staring out of windows, but very little time making any work. I’ve been feeling really stuck, unsure about what to do next, and struggling with a lot of self-doubt and confusion.

After dinner, I walked across the street to the Lincoln Center fountain, and I sat on the granite slab next to the water. The night was dark and cold. Operagoers in tuxedos rushed to get taxis. I could feel the black stone below my body. I looked at the city sky but I couldn’t see stars. I turned my head to look at the water. The columns of water were moving up and down in some kind of pattern, but I couldn’t tell what it was. Sometimes the columns of water were tall, and moving up and down within their tallness. Other times, the columns of water were low, and moving up and down within their lowness. The columns of water were never not moving.

I thought about stuckness, and about where I lost the flow. I remembered other times in my life I’d been stuck, and how the stuckness always eventually passed. I thought how life is a lot like that fountain, with its columns of water moving up and down, and how the low points are actually thrilling because the high points are about to come back, and how the high points are actually terrifying, because the low points always come next.

I thought of my life as a series of chapters, and I realized that each time I’d been majorly stuck, it meant that a life chapter was ending, and that a new one needed to start — like the stuckness was always a signal indicating imminent change. My life has had a bunch of different chapters, each one beginning with the fresh-faced idealism of a new approach to living, and each one ending with a period of stuckness and a moment of crisis. I’d like to tell you about those chapters, in case they contain something useful for you.

I should say up front that I’m lucky to make a living mainly by giving talks about my work at conferences, companies, and universities, which affords me a lot of time each year to make new work (and to obsess endlessly about what that work should be). In Zen philosophy, they say that anything pushed to its extreme becomes its opposite. Sometimes I wonder whether too much freedom produces a weird kind of psychological paralysis, which is almost like prison. Still, obviously I’m grateful to be grappling with too much freedom instead of too little.

Paint (1995-2003)

Paint — a foggy field in Deerfield, Massachusetts, with pages from my travel journals.

In high school, I was a total romantic. I had a field easel, and I’d stand around in meadows doing oil paintings while wearing a little beret. In college, inspired by the travel journals of Peter Beard, I kept elaborate sketchbooks filled with dead insects, pasted plants, ticket stubs, watercolor paintings, photographs, and writing. I made these books by hand and kept them for several years. At the same time, I was studying computer science in the early days of the Internet, and I felt a growing rift between the sober art of painting and the dizzying potential of the web. I couldn’t find a way to bridge these two worlds, and I started to feel torn — partly pulled into the future, and partly stuck in the past.

I’d graduated from Princeton but was still living in town, doing odd jobs and generally feeling bad about myself and unsure about what to do next. I took a trip to Central America and ended up getting robbed by five guys who put a gun to my head, beat me up pretty badly, and stole my bag, which contained a sketchbook with nine months of work. It was one of those odd moments in life that’s really traumatic, but which ends up being a doorway into something new. After the robbery, I gave up painting, stopped keeping sketchbooks, and resolved to use computer code as my new artistic medium. I wanted to make things that guys with guns couldn’t steal. Around this time, I received a one-year fellowship at Fabrica, a communications research center in northern Italy. I moved to Italy, and I started writing code.

Data (2003-2008)

Data — coding I Want You To Want Me in my old apartment in Brooklyn, New York.

I became obsessed with the potential of data to tell me everything I’d ever need to know about life. I could sit safely at my desk and write computer programs to gather vast amounts of Internet data, which I thought could finally answer timeless questions like “what is love?” and “what is faith?” with precision and clarity. With manic self-confidence, I pumped out project after project visualizing different data sets, pairing each project with a bombastic artist statement about how the work revealed insights about humanity that had previously been hidden.

There was We Feel Fine (a search engine for human emotions), Universe (a system for deducing new constellations for the night sky), I Want You To Want Me (a study of online dating), Lovelines (a portrait of love and hate), 10×10 (a distillation of global media coverage), Phylotaxis (a visualization of science news), and Wordcount (an exploration of language).

My data visualization work coincided nicely with society’s increasing obsession with data-based reasoning, which was infiltrating nearly every aspect of our lives — from news, to sports, to finance, to education, to politics, to healthcare, to dating. Because of this, I got lucky, and had some early success. I got to speak at TED, got a commission from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, showed my work at Sundance, appeared on CNN and NPR, and companies started paying me to give one-hour lectures about working with data. I quit my job, and spent all my time giving talks and making work.

I burned through projects and people, devouring a series of relationships that never seemed as interesting as my work. I was full of pithy insights about human emotion to spout at cocktail parties, but I started to notice that my data-based insights did very little to help my actual relationships. I began to grow suspicious of data. My insights felt increasingly superficial, and though they made me sound clever and witty, they didn’t do much to help me be kind. The world’s love affair with data was just heating up, but mine was cooling down.

MoMA commissioned the last data-based work I made: a project about online dating, called I Want You To Want Me. I’ve never worked harder on anything. For three months, I spent eighteen hours a day in front of a five-foot-wide touchscreen, poring over hundreds of thousands of dating profiles, and writing over 50,000 lines of code. I’d go for walks in the evening around my neighborhood in Brooklyn, and I’d look into restaurants at actual couples on actual dates, unable to imagine what they could possibly be saying. My mind was completely inside the machine, and I’d never felt more alienated from other human beings. I guess I thought the MoMA commission would somehow change my life, catapulting me into even higher echelons of fame and attention. But that didn’t really happen. The show went up, there was a big party, and then people basically went back to their lives.

I didn’t know what to do next. I went on some Internet dates, but it was hard to connect with anyone, and I just ended up feeling worse about myself. I started to get really depressed. I went down to Texas. I drove out to Marfa and saw the Marfa lights. I drove to the Mexico border and waded across the Rio Grande into a desolate Mexican town. I slept out in the desert under the stars. Being away from computer screens, I started to feel better. A sense of adventure and possibility crept back into my life. I’d meet strangers in diners, and it would feel good to talk to them. I started to feel human again. I liked the feeling of rambling around, getting into strange situations, and actually living life in the physical world. I decided to start making projects about the real world — where instead of using a computer, I’d do the “data collection” myself. I’d take photos. I’d shoot videos. I’d record sound. I went back to New York to get started.

Documentary (2008-2010)

Documentary — characters from The Whale Hunt, Balloons of Bhutan, and I Love Your Work.

Instead of trying to be the smartest person in the room, now I wanted to be the most interesting. Many people make choices to try to be better people — they take up yoga, they become vegetarian, they resolve to spend more time with their parents. Often, I use my work as a way to steer my life in a particular direction. I’ll identify something I want to change about myself, and then I’ll design a project to help me do it. In this case, I felt like I’d never really become a man. My childhood friends in Vermont were hunting deer, building houses, running farms, and being dads. I was just typing into computers, writing clever programs, and looking for praise. I wanted to change that. I wanted to live a bolder life, and I designed a series of projects to force me to try. I went whale hunting in Alaska. I traveled to Bhutan to learn about spirituality and happiness. I filmed the everyday lives of lesbian porn stars in New York. For each of my deficiencies (masculinity, wisdom, sexuality), I designed a project to help me confront it, which I hoped would help me transcend it. In a way, this worked. My life suddenly got interesting. People were curious. I always had outrageous stories to tell. I’d present these stories in intricate interactive frameworks of my own design, and I’d release them on the web. Again, I got lucky. My work with interactive storytelling coincided with society’s increasing obsession with “storytelling” in all of its forms.

Storytelling, which used to be a reasonably small niche populated by organizations like This American Life, The Moth, and StoryCorps, was suddenly everywhere. Every advertising agency was now a “storytelling agency,” every ad campaign was now a “storytelling campaign,” and every app was now a “storytelling tool.” Storytelling had gone mainstream and become one of those words — like “sustainability” and “innovation” — that’s so ubiquitous as to be basically meaningless. Yet through all this, I was riding the wave.

The World Economic Forum named me a “Young Global Leader,” citing my storytelling work. I was constantly being invited to trendy cocktail parties in New York. I was flying all over the world to give lectures. My life was moving very fast, but I began to feel like a fraud: I was wearing my stories like armor, telling the same winning tales again and again to laughter and praise, but never going deeper, and never revealing myself. I began to feel like a hunter, constantly chasing down the next story to win me acclaim. Since all my stories (like most documentaries) basically belonged to other people, I also began to feel like a thief.

One night, I hosted a dinner party for twelve at my apartment in Brooklyn. We stayed up till five in the morning and drank eighteen bottles of wine. My friend Henry stayed over, sleeping on the couch. At 7:00 a.m. a loud BOOM awakened us; the whole building was shaking. We rushed to the window to see that a car had crashed into the building; only its trunk was poking out of the hole it’d smashed in the wall. Smoke was rising from the hood. We ran into the street in our underwear, unsure if the car was about to explode (luckily, it didn’t).

I took the car crash as a sign to leave New York and find a new direction. I wanted to slow down. I wanted to simplify my life. I wanted to find balance again. I didn’t want to rely on other people’s stories. I didn’t want to be a thief anymore. Instead, I decided to hold a mirror up to myself and tell my own stories.

Autobiography (2010-2011)

Autobiography — my cabin in the woods in Sisters, Oregon, watched by an owl.

When I turned 30, I left New York, bought a car, and drove across the country to Oregon, where I spent four months living in a little log cabin in the woods. I’d see another person about once every four days when I traveled to town to buy groceries. I started a simple ritual of taking a photo and writing a short story each day, and then posting them on the Internet each night. I continued this ritual for 440 days, and I called the project Today.

At first, Today was a wonderful addition to my life. I found myself becoming more aware of the world around me, more capable of connecting with others, and better at identifying beauty. I became obsessed with life’s “teachable moments” — the little things each of us encounters that might have a teachable value to others. I got good at spotting these teachable moments and condensing them into little narrative nuggets, so that others could digest them. I began to understand that principles delivered out of context will never be remembered, and that telling people the story of how you came to hold a given principle is better — so it’s like they lived through it themselves. I got obsessed with the potential of stories to communicate wisdom, but at the same time, I began to understand that really, you can’t teach wisdom — it has to be won by experience. Stories can alert you to the existence of certain truths, but you never really embody those truths until you reach them on your own.

I traveled from Oregon, to Santa Fe, to Iceland, to Vermont, doing a series of art residencies, living like a hermit, and continuing my daily photo project. More and more people began to follow along, until an audience of several thousand strangers was observing the intimate details of my everyday life. This began to be a burden. The project took on a performative quality; I found myself intentionally hunting down interesting situations, just so I could write about them that evening. I found myself plundering the relationships in my life for material, often with damaging consequences. I began to feel like a spectator to my own life, unsure whether to document it or simply to live it.

During this time, I fell in love with a young woman named Emmy. She was working at the art gallery in Vermont where I had a show. We only knew each other briefly, but when she chose to leave me for her ex, I was devastated, and for a couple months, I could barely get out of bed. This was probably the lowest point in my life. My daily stories around that time were brutal and strange, and my family and friends began to worry that I was in danger of harming myself. At that point, the daily stories were simply too much, and I abruptly decided to stop the project. I sent a brief email to the people following it, saying I wouldn’t be doing it anymore, and thanking them for their attention.

Within an hour of sending that email, I received over 500 responses from people all over the world, telling me how much the project meant to them, and thanking me for doing it. Most of these people I’d never heard from before. One woman in the UK said the project had kept her from killing herself, because it gave her hope each day to keep going. Many people said they’d never written before because they never knew what to say, but that my daily story was their favorite part of each day.

I never imagined that such a simple project — just a photo and some of my thoughts — could touch so many people so deeply. It made me realize that the most powerful things are often the simplest, as long as they’re made honestly and with a lot of heart. It also made me believe in the power of personal stories, so I decided to make a tool to encourage other people to tell them.

Tools (2010-2013)

Tools — coding Cowbird in Siglufjörður, Iceland, under the aurora borealis.

I set out to create Cowbird, a storytelling platform for anyone to use. My dream was to build the world’s first public library of human experience — a kind of Wikipedia for everyday life. After making so many projects for people to look at, I wanted to make something for people to use.

I thought Cowbird would change the world. I thought it would become the anti-Facebook, harnessing a growing desire for substance, and that millions of people would use it. It was simple and beautiful, and brimming with detail, sincerity, and depth. I worked on it alone in isolation for two years, with monomaniacal certainty that people would love it.

During that time, the world changed. Storytelling apps became commonplace. Internet use went mobile. Tablets went mainstream. Geolocation emerged. I noticed these things, but I ignored them. I worked with single-minded focus on Cowbird, sticking to my original vision, which became increasingly out of touch with reality. By the time Cowbird finally launched, it joined a crowded field of storytelling apps (Instagram, Path, Facebook, Vimeo, Tumblr) with more to follow (Medium, Vine, Wander, Days, Storybird, Maptia, etc.). All these apps were basically the same — ways for humans to share photos, videos, and text — and this process began to bore me.

But I was living in northern California near Silicon Valley, and everyone urged me to do what everyone out there does, which is to start a company and raise money, so that’s what I did. I hired fancy lawyers for $850 an hour, founded a Delaware C-Corp, and arranged an angel round of $500,000 from a dozen investors, using a convertible note. This whole process felt icky to me, but I did it anyway — it was simply what everyone in California did. Right before we signed the paperwork, I had to fly to Spain to give a lecture.

For the first time in months, I had a few days away from computers and away from Silicon Valley. I wandered the streets of Barcelona, sat in cafes, and thought about the life I wanted to live. I watched old Catalonian couples walk hand in hand through leafy plazas. The women wore ankle-length dresses, and the men wore clunky shoes and fedoras. They walked slowly, said hello to friends, looked around at the buildings, and up at the trees. It was a world away from the frantic ambition of Silicon Valley — here it was just human beings living their lives.

A couple months earlier, a wealthy Internet friend had invited me on a sailing trip to the British Virgin Islands. One day, we visited Richard Branson’s private island. I was struck by Branson’s humility; even with all of his fame and success, he’d never stopped being kind — maybe that was his secret. It was interesting to see his life — the secluded tropical island, the flamingo colony, the giant tortoises, the lemurs, the bungalows, the sailboat races, the assistants, the phone calls, the beautiful people. This was the endgame of the money life, and it made me realize it wasn’t for me.

When I think about my own future, my dream is always the same. I’m living in a small beautiful farmhouse in a small beautiful town among a small community that values me. I’m living with a wife and kids I love deeply, and I spend each day making art and watching nature. My mind is clear and calm, I’m in control of my time, and I’m kind.

In a cafe in Barcelona, I decided not to take the investment money. In my heart, I realized I just didn’t want to run a company. I didn’t want to sit in meetings, manage people, market products, raise money, and send emails all day. Really, I just wanted to make small, beautiful things.

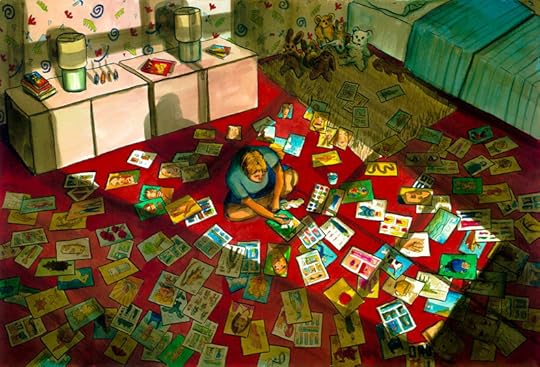

Getting unstuck

Getting unstuck — in my childhood bedroom in Shelburne, Vermont.

All we have in life is our time. People struggle after success. They hunger for fame, fortune, and power. But in all of these things, the same question exists — what will you do with your time? How do you want to spend your days? As Annie Dillard reminds us, “how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

In life, you will become known for doing what you do. That sounds obvious, but it’s profound. If you want to be known as someone who does a particular thing, then you must start doing that thing immediately. Don’t wait. There is no other way. It probably won’t make you money at first, but do it anyway. Work nights. Work weekends. Sleep less. Whatever you have to do. If you’re lucky enough to know what brings you bliss, then do that thing at once. If you do it well, and for long enough, the world will find ways to repay you.

This fall, in a toilet stall in Burlington, Vermont, I saw this scrawled on the wall:

“Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive. The world needs more people who have come alive.”

If you’re doing something you love, you won’t care what the world thinks, because you’ll love the process anyway. This is one of those truths that we know, but which we can’t seem to stop forgetting.

In America, success is a word we hear a lot. What does it mean? Is it money, power, fame, love? I like how Bob Dylan defines it: “A man is a success if he gets up in the morning and gets to bed at night, and in between he does what he wants to do.”

We have these brief lives, and our only real choice is how we will fill them. Your attention is precious. Don’t squander it. Don’t throw it away. Don’t let companies and products steal it from you. Don’t let advertisers trick you into lusting after things you don’t need. Don’t let the media convince you to covet the lives of celebrities. Own your attention — it’s all you really have.

In the tradeoff between timeliness and timelessness, choose the latter. The zeitgeist rewards timeliness, but your soul rewards timelessness. Work on things that will last.

Inside each of us is a little 10-year-old child, curious and pure, acting on impulse, not yet caring what other people think. Remember what you were doing at ten, and try to get back to doing that thing, incorporating everything you’ve learned along the way.

When I was ten, I was writing words and drawing pictures.

Maybe that’s the path out of the stuckness.

This post was originally published at Transom and is reprinted here with permission.

The post Navigating stuckness appeared first on Matador Network.

Is this video the new Gangnam Style?

SOMETIMES, THE BEST things I find on the internet, I don’t understand at all. This video, performed by MMA fighter Genki Sudo and his posse, World Order, is so random, crazy, unique, and uplifting, I can’t help but bop along to the beat. But is it only random, crazy, unique, and uplifting because I don’t speak Japanese, and therefore, the translation is lost to me? What is this video even about?

The group’s robot-like synchronization, coupled with adorable Japanese pedestrians who were lucky enough to get in the way, equals one fun, catchy music video with quirky dance moves that may make everyone forget PSY ever existed (if you haven’t done so already). I enjoy knowing that elsewhere in the world, people aren’t famous for “twerking,” but from just asking people to “have a nice day.”

The post Is this music video the new ‘Gangnam Style’? appeared first on Matador Network.

Travel is beautiful

Travel Is from The Perennial Plate on Vimeo.

OUR FRIENDS at Perennial Plate and Intrepid put this incredibly inspiring edit together to celebrate Intrepid Travel’s 25th Anniversary. How is travel beautiful to you?

The post Travel is beautiful appeared first on Matador Network.

London has better food than Paris

Photo: Garry Knight

I spent the last couple of weeks in London and Paris with my girlfriend. I’d been to both cities plenty of times before, so instead of trying to see all of the major museums and tourist sites, we adopted a new approach to the trip: “Eat our way through Paris. Drink our way through London.”

It was an obvious choice: Paris is known as one of the culinary capitals of the world, and London is perhaps best known for its pubs. But a few days after leaving Paris, we stopped at Borough Market on London’s South Bank, and I ordered a roast pork sandwich from one of the booths.

“Holy shit,” I said. “This is the best thing I’ve had all trip.”

As the week continued, I realized virtually all of my meals in London were better than all of my meals in Paris. And not just on this trip: I have yet to have a meal in Paris that I’ve been truly wowed by. Ever. Sure, the coffee’s great. But for Christ’s sake, a croque monsieur is just grilled ham and cheese. My mom made that shit for me when I was five if she was in a rush.

London, on the other hand, has long been declared a culinary wasteland. Images of gloppy mounds of starchy potatoes and overcooked meat smothered in gravy — which they often more accurately just call ‘brown sauce’ — are what travelers usually think of when they think of London. Often, you’ll hear the cliche, “You can find good food in London, but you can’t find good British food.”

There are a few reasons this is unfair. First of all, what is and isn’t British food is changing over time. As much as the Brits often hate to admit having a foreign influence, they were once the rulers of half the planet, and cultural exchange goes both ways. Tikka masala, a standard Indian staple here in the United States, was actually probably invented in Britain. And coronation chicken, a curried dish created for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, tastes more ‘Indian’ than it does ‘British.’

So you don’t get to say, “There’s great Indian food in London,” but not count it towards London itself. If you do, you can’t count any dishes with a foreign influence towards other great international cities like New York. What’s New York cuisine without pizza? (Pizza, incidentally, is one thing London is flatly not able to do well. As one New Jerseyan said to me in London, “I love the food here, but I cannot get a good fuckin’ slice of pie.”)

“It’s only in London that you find every conceivable style of cooking. When it comes to what’s new in cooking, to innovative cuisine, it’s all happening in London.”

Second, a lot of the people saying London’s food sucks are getting that food in a pub. London is chock-full of pubs, and while the trend of gastropubs is on the rise, they’re not typically known for their food. And while all food should to some extent count towards a city’s score, I think pub food should get a little less weight. Here in DC I usually know what the quality of food is going to be when I order in the bar: It’s just there to soak up the alcohol.

Paris, on the other hand, has gotten lazy. Don’t get me wrong — Paris is way ahead of most cities on the strength of its wine, cheese, and bread alone. But it’s kinda coasting otherwise. I felt the same way about Parisian food as I felt about a lot of the art in its many museums. I know I’m supposed to like this, but really, I’m just bored.

My girlfriend and I hopped from cafe to restaurant, cafe to restaurant, and we just couldn’t find a particularly good meal. Maybe I’ve just been unlucky every time I’ve been to Paris. Maybe I’ve been in the wrong neighborhoods. Maybe I’ve lacked a proper tour guide. But even following the suggestions of Parisians has led to just okay food.

And while as of last August London had a total of 69 Michelin stars to Paris’s 101 — a restaurant with 3 Michelin stars is considered among the best in the world, and Michelin-rated restaurants are usually very expensive — I would argue that high cuisine does not a good food city make. Because eating is universal. If the poor and middle classes can’t eat there, what’s the point?

On top of this, it’s usually the poor who are preparing our food. In America, as is often pointed out by Anthony Bourdain, many of our best line cooks are poor immigrants who couldn’t afford the dish they’re making for others. As such, I give stronger weight to delicious food from a pushcart or a dive joint, simply because the standard is so much higher for haute cuisine.

I’m not alone in thinking this. One of the world’s best chefs, Joel Robuchon — a Frenchman, nonetheless! — should be considered the culinary capital of the world.

“Why?” Robuchon said in an interview with the London Evening Standard, “Because it’s only in London that you find every conceivable style of cooking. When it comes to what’s new in cooking, to innovative cuisine, it’s all happening in London.”

So, by the power vested in me by Matador Network, I’m calling it: London has better food than Paris.

The post I’ll go ahead and say it: London has better food than Paris appeared first on Matador Network.

30 signs you're a jiu-jitsu addict

Photo: MartialArtsNomad.com

Your joints are sore and your ears are mangled, yet you still spend the entire day looking forward to training. Are you worried that you’re addicted to Brazilian jiu-jitsu? Take a long look at this list and judge for yourself.

1. You hip escape in bed to get out from under the covers.

2. You’re uncomfortable hugging your own mother without double underhooks.

3. Your closet is filled with more jiu-jitsu gis than t-shirts and jeans.

4. You find yourself debating whether or not to pass the guard during missionary sex.

5. You pronounce names beginning in “R” with an “H” sound.

6. Laundering your dirty gis has resulted in several destroyed washing machines.

7. You delete your web history so your significant other doesn’t see your jiu-jitsu watching habits.

8. You find your jiu-jitsu skills improve the more you train, yet your English gets worse.

9. All the t-shirts you do own are emblazoned with jiu-jitsu tournament graphics.

10. You’re on a first-name basis with your local seamstress.

11. You’ve been accused of having an affair as a result of hickey-like bruises on your neck.

12. When someone extends their hand, you don’t think “handshake,” you think “armdrag.”

13. Acaí, picanha, and caipirinhas are staples of your diet.

14. You can pronounce açaí, picanha, and caipirinha with ease.

15. You’ve unintentionally learned to speak Portuguese despite living in middle-America.

Photo: John Lamonica

16. You’ve been given the “it’s me or jiu-jitsu” ultimatum more than once in your life.

17. You chose jiu-jitsu every time.

18. You’ve sprained every finger and toe more than once.

19. You only plan vacations to places in close proximity of a jiu-jitsu academy.

20. The term “rear naked choke” doesn’t remotely remind you of sexual activity.

21. You have no problem defending yourself, yet shaking hands with an acquaintance hurts.

22. You’ve considered living at the jiu-jitsu academy in order to save commuting time.

23. Upon meeting someone, you inspect his/her ears before making eye contact or smiling.

24. You have expert-level mopping skills due to your daily post-training duties.

25. Several times a week, you skip your lunch break at work to go train.

26. Your budget includes an allocation for Mueller athletic tape.

27. You’re no longer scared of needles after draining your own cauliflower ear.

28. You carry your gi everywhere on the off-chance you might pass by the academy.

29. “Berimbolo,” “Kimura,” and “De La Riva” don’t sound like gibberish to you.

30. You found this list humorous, yet unsurprisingly applicable.

If you found yourself nodding or laughing at this list more than a few times, go get some help. Or better yet — as Kurt Osiander says, “Go train!”

The post 30 signs you’re a Brazilian jiu-jitsu addict appeared first on Matador Network.

March 27, 2014

How to piss off a Canadian-Jamaican

Photo: Adrian Araya

I’VE SPENT MOST OF MY LIFE around my Jamaican family and a good part (okay, all) of my formative years practicing the art of pissing them off. I consider myself somewhat of an expert in riling up a Jamaican, but I’m not a Jamaican. I’m Canadian-Jamaican, which brings with it different scenarios that result in being pissed off.

Ask where we’re really from.

I remember reading this in my tenth grade Civics textbook: Canada is a “cultural mosaic” — Canadians retain their unique ethnic identity while contributing to the nation as a whole.

We’re pretty damn proud of it, too, if only because it stands in contrast to the American “melting pot” assimilationist culture. For that reason, people think it’s okay to open a conversation thus:

“Where are you from?”

“Canada.”

If you want to get even more of a reaction, put a confused look on your face and throw in a “really” for good measure.

“No, where are you really from?”

“Toronto.”

“Yeah, but where were your parents born?”

“Jamaica.”

To really get us going, follow it up with this:

“You’re Jamaican? Awesome — I love Bob Marley!”

You and pretty much the entire world. Seriously. We enjoy Bob Marley’s music, too, but we did grow up in Canada. We liked Nelly Furtado and Celine Dion just as much as the next guy.

In a way, we’re just glad you didn’t say Sean Paul or someone embarrassing like that, but if you really want a pat on the back, say you love Beres Hammond or Tarrus Riley. Then we can talk — as long as you don’t ask this:

“Do you know how to speak ‘Jamaican’?”

You mean English? Because that’s the country’s official language. Our parents speak English, our grandparents speak English, and so on, albeit with an accent. Now, if you’re referring to Jamaican Patois, which we suspect you are, then the answer will always be “no” if we think you’re going to try and make us say something. Once we do, it either results in laughter or squeals about how cool it is.

For those of Jamaican descent who didn’t live in Jamaica at all, we don’t always have the most positive attachment with Patois — we generally only heard it growing up when we were in trouble with our parents. If we were lucky enough to have other Jamaican classmates, we may have used it to make fun of you for asking such an annoying question, though.

Quote Cool Runnings to us.

“Sanka, ya dead?” The number of times we’ve heard that line butchered is enough to make our blood boil. The original line was butchered in the first place. Cool Runnings was actually based on a great story that could have been an interesting study of racism in sport and beating the odds. Instead, it has become a punchline.

Most of the actors playing Jamaicans in the film were not Jamaican, their accents were terrible, and it played up stereotypes about Jamaicans. The fact that you’re quoting it only perpetuates this caricaturization of Jamaicans in film, so think for a second before you do that after saying how much you love it.

This also applies to saying “No problem, mon.” We will wish excruciating pain upon you.

Assume that all the men in our family have dreadlocks and are Rastafarian.

Only 3% of Jamaicans practice Rastafari. From what I know about Rastafari (Note: Don’t add the -ism — that’s part of the “Babylon culture” they are critical of), they don’t practice in traditional churches and Jamaica actually has the most churches per square mile in the world. Most Jamaicans are Christians, and that generally applies to our families as well.

Insist that wine is a drink.

Rum and Red Stripe are drinks. Wine is a dance. Maybe you want to call it “twerking” and bring up Miley Cyrus, but Jamaicans were doing it long before the teen queen was even born.

Assume all we ate growing up was jerk chicken.

Only for dinner, actually. For breakfast we had Jamaica’s national dish, ackee and saltfish, with fried plantains and fried dumplings. For lunch, oxtail stew over rice and peas with breadfruit. As a snack, we would have a Jamaican patty with cocoa bread. Then, and only then, did we have jerk chicken served up with steamed callaloo, boiled green bananas, Irish potatoes, and yams, a side of freshly pressed sugarcane juice and pineapple and rum upside down cake, made with pineapples shipped straight from the motherland, for dessert.

Or we had pasta. It was a tossup.

The post How to piss off a Canadian-Jamaican appeared first on Matador Network.

12 surprising facts about emoticons

Photo: Holger Eilhard

YOU PROBABLY take emoticons for granted. I do. Colon-parenthesis is a smile. Semi-colon-parenthesis is a wink. Colon-capital-P is a tongue sticking out. For many of you these have probably been a part of your vocabulary since you remember. They just are. But they haven’t always been. Here’s a history lesson for you.

Your brain reacts to emoticons as if they were real faces, according to a recent study in the scientific journal Social Neuroscience.

The first email smiley face was sent at 11:44 am on September 19, 1982.

The message was not originally saved (they were able to retrieve a copy 20 years after the fact).

Colon-dash-parenthesis was invented by Scott Fahlman, a research professor at Carnegie Mellon’s School of Computer Science.

The smiley face was created to mark a lighter or sarcastic tone in the simple text messages and avoid misunderstandings and fights.

The first idea to mark messages as “not serious” was to use an asterisk in the subject line. Scott thought he could do better than that.

It started being used just within the school Scott worked in, then spread to other schools but was limited to how many were joined — at that point, around 10 — over the ARPANET (the Internet in those days).

As more schools joined the network they would take on the use of the smiley face, expanding its reach and use.

The inventor of the text smiley face doesn’t like emojis, the graphic illustration of the character-based emoticons. He thinks they’re ugly.

Some people challenge the validity that Scott invented the first emoticon; a transcript from 1862 of an Abraham Lincoln speech apparently contains a winkey smiley face.

It’s theorized that this winkey smiley face in Abraham Lincoln’s speech is just a typo.

Scott doesn’t claim to be the inventor of emoticons; he just invented colon-dash-parenthesis.

Below is an entertaining interview with Scott Fahlman on CBC’s “Q”:

The post 12 facts about the emoticon’s history that may surprise you appeared first on Matador Network.

How we'd use Oculus Rift travel

FACEBOOK IS IN THE PROCESS of buying up technologies for huge sums of money, and the latest asset they’ve acquired is the company behind the head-mounted Oculus Rift virtual reality system.

The Oculus Rift started as a Kickstarter campaign geared mostly towards gamers — which is what it’s going to be primarily used for. We here at Matador, though, think it shouldn’t stop there: Any number of real-world virtual experiences could be created using Oculus technology, including travel experiences.

Here are ten of the VR travel experiences we’d love to see with the Oculus Rift:

1. Standing at the Sun Gate, looking down on Machu Picchu

2. Floating along the canals of Venice

3. Flying up through the girders of the Eiffel Tower (no elevator lines!)

4. Soaring down over the edge of the Grand Canyon, eagle-style

5. Scuba diving the Great Barrier Reef

6. Hang gliding over Maui

7. Going into low Earth orbit with the International Space Station

8. Heli skiing the mountains of Alaska

9. Trekking in Nepal

10. Running with the Bulls in Pamplona, Spain

What travel experiences would you want to try through virtual reality technology?

The post 10 simulated travel experiences we want to see with Oculus Rift appeared first on Matador Network.

What it’s like to be gay in Russia

Photo: Nuria Fatych

Being gay in Russia is now a criminal act, and journalist Jeff Sharlet spent several weeks profiling a group of Russians who have increasingly gone underground or even into exile. His research culminated in a GQ article: Inside the Iron Closet: What It’s Like to Be Gay in Putin’s Russia.

Sharlet describes how Putin’s government, along with the Russian Orthodox Church and what he calls a fringe element — mostly tough-guy homophobes — work together in an “unholy trinity” to crack down on the country’s queer population. Violence against gays and widespread discrimination have been codified by a law that bans gay “propaganda” — a law that was passed by Putin’s government in June of 2013.

“The law is straight out of Russian literature,” says Sharlet.

We recently caught up and talked about the restrictions queer people face in the same country that hosted this year’s Winter Olympics.

* * *

AH: You say early on in your article for GQ that civil society in Russia is imploding. I found that a really succinct way to explain a complicated concept.

JS: I think when I wrote that, it was before the invasion of Ukraine, and there were a lot more Putin apologists around. And I think there’s a sort of implicit assumption that a European nation with wealth is somehow in one way or another moderate in its governance. It’s just like how there are certain people who’ll say that all the anti-gay laws passed in Uganda were passed because it’s an African country. That’s just some old racist bullshit.

Putin’s government is no longer interested in even maintaining some kind of human rights norms. At least for LGBT rights, things [before Putin] were getting better — there were political lines you couldn’t cross, and now that’s turned around, I think not just for LGBT people. Putin has decided to really rule with a fist.

But the real keyword in that was imploding, I didn’t want to say it [civil society] was destroyed. Some of the aspects are still there — in terms of youth sports leagues — that’s all there, and that’s all intact. But in terms of NGOs, the ability for people to pursue sometimes political things, sometimes non, and freedom of the press — publishing, the banning of books. There’s sort of a larger sense of restriction on culture.

Is the gay community going increasingly underground?

It’s going underground or into exile, if you’re a middle-class person, if you have the resources — a lot of those people are looking into leaving. If you have kids I think it’s insane for you to not be investigating it. Laws like this are not made to be enforced. They’re made to terrify people.

One story I couldn’t fit in was about a lesbian couple with a kid. They were friendly with their neighbors, and their kids all played together. But since the law has passed, the heterosexual couple has decided to supplement their income by blackmailing the lesbian couple. [They’re threatening to turn the lesbian couple in to authorities if they don’t pay a certain amount of money.]

People have gone back into the closet, and there’s a whole generation of people who aren’t going to come out at all.

Given how scary it is to be openly queer in Russia right now, how did you actually meet LGBT people?

I had written about Uganda; I had a lot of connections with LGBT rights organizations. But my method as a writer is I don’t go with lots of important people lined up. I’m interested in regular people. To meet the people who become characters in the story, you go from person to person, you have a lot of conversations until someone connects you to a friend.

I knew going over that I was going to work with a regular translator. Zhenya [a queer activist] was just my kind of translator. He’s not a regular fixer. I knew I needed a queer translator. I’d already made that mistake in Uganda (of having a straight translator). Zhenya had been in exile, and so he was rediscovering his country sort of right alongside me.

In the story we meet a lesbian couple and a gay couple who pose as two separate straight families, who live next door to each other. You write, “In an upper-middle-class neighborhood close to Moscow’s city center, two apartments face each other. Two families, two daughters. They leave the doors open to allow easy access from one to the other.” In fact, the couples have raised two daughters together. So each daughter has two dads and two moms. The arrangement defuses suspicions that the daughters’ parents are all queer. I found this family, and the lengths they go to in order to stay safe, fascinating.

That family is so sad. I don’t know what will happen to them. I don’t think it’s going to be good. I think they will be broken up. Nik was a profoundly square man. This was a family man. Not an activist in any sense. He felt like he’d been pushed to the edge. He had met this woman. They just decided to have a family. That’s what he wanted. He realized as an adolescent that he was gay and also wanted to have a family. Then later he met Pavel, his partner.

You can sense the love he feels for his daughters.

Oh, I mean it really is, it’s very powerful. It’s [being in the closet] sort of — it’s driving him crazy. To me, I have two little kids, the thought of having to teach them that they could never call me father — there’s something so perverse about that.

Of course, in a country like Uganda, things are much worse. But there’s a way this law is like a law out of Russian literature. It’s perverse. It is a truly unnatural law.

You know in Uganda they banned homosexuality. But Russia, in a way, outlawed love. It is literally a crime for you to say that you love your partner as much as a heterosexual person loves her boyfriend. To assert equality is the crime.

While you were in Russia you visited several gay clubs. You used small vignettes of club life to break up your story. What was it like visiting these places given the atmosphere of fear and government crackdowns?

My editor wanted club scenes, and not only am I not a club person, but I was thinking, how am I going to get in? I don’t look… You don’t want me there! And Zhenya, my punk-rock translator, felt the same way. But we did end up there. And we pretty much covered the whole scene in two weeks. I would often go into the club and feel like I’m such a fucking dork here.

A lot of those people [who frequent clubs] feel like the law doesn’t affect them much at all. If you’re 22, unmarried, and living in Moscow, your day can begin at midnight. I met a gay go-go dancer, and he didn’t really know what’s going on in the rest of the world.

And I felt that without these vignettes of club life we have only villains and heroes. But the truth is, not everyone can become Rosa Parks, oppression breaks people.

And on the note of oppression, it seems to operate in a deeply wound-together system in Russia. Could you explain more about what you call the trilogy of Putin, the Russian Orthodox Church, and the homophobic fringe element?

Yeah. The sort of unholy trinity.

The trinity is the flipside to civil society is imploding. [It operates with] a kind of brutal efficiency, which is true of homophobias in all places. We don’t always recognize that it’s not just backwoods evil people hurting queers — in the case of Russia, the state harnesses the church, the church has been so long suppressed and confused about its identity, and then there’s the rabble of the nationalist thugs.

They all get legitimacy from each other. The state needs the legitimacy of the church, the church needs the power of the state, and of course the rabble could use their energy to confront the fact that they don’t have a lot of economic opportunities, or [the thinking goes], “We could just go beat up a faggot and feel better faster.”

Homophobia is a giant bureaucracy of hate.

From your article I came away with the sense that anti-gay lawmakers in Russia learned their tactics from the American right wing.

There are many channels through which this is going. They get it from the American Family Association and the Family Research Council. One Russian lawmaker was deeply informed by the phony social science of the American Right. Homophobia in America is supposedly on the run, but we don’t recognize that some of the phony social science is being churned out by mainline academia as well.

The contemporary right wing is based on ideas, and ideas travel. There’s no conspiracy. There just need to be really awful ideas that can be amplified across other countries. They couldn’t pass the Arizona law [SB-1062], but they can contribute to those ideas becoming law around the world.

The post What it’s like to be gay in Russia appeared first on Matador Network.

Aerial video of a dolphin 'stampede'

Yes, there is such a thing as a dolphin stampede, and, yes, it’s awesome. Dave Anderson, who runs Captain Dave’s Dolphin and Whale Watching Safari in California, managed to capture a “mega pod” (a large group) of dolphins stampeding using a GoPro mounted on a quadcopter drone. He also caught some pretty sick footage of whales from above.

Video like this is enough to convince me that, while Obama’s drones are bombing villages in Pakistan and Yemen, and while Amazon’s drones are murderous sentient death machines, not all drones are bad — we should try to use them as much as possible if it helps us get even more incredible wildlife footage.

The post A drone-mounted GoPro captured this footage of a dolphin ‘stampede’ appeared first on Matador Network.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers