Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog, page 50

December 21, 2022

Were the Wright Brothers the First to Fly?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Humankind has envied birds and other flying animals for millennia. The sheer exhilaration, the freedom, the ability to eschew busy airports and pricey flights… wings certainly are quite the evolutionary boon! There’s a reason why one of the most-ballyhooed superpowers displayed in comic books and other media is flight.

In Scott Lobdell and Pascal Alixe’s “Red Hood and the Outlaws #14,” per CBR, Superman takes just seconds to fly from the distant Pluto to the Earth he so loves. Considering that the distance between the two is 2.66 billion miles (4.28 billion km) at the furthest point of their orbit, it’s clear that this is infinitely far beyond anything that’s even remotely realistic. That’s part of the fantastical appeal of flight, though.

For the first bold pioneers of aviation, vehicles that could actually carry us into the air may have seemed equally impossible. Through their perseverance and ingenuity, though, some of the furthest reaches of the globe are accessible. We can enjoy travel on a scale that would have seemed far beyond our reach just a century ago.

Who do we have to thank for this? For many, the Wright Brothers are considered the true pioneers of flight. The truth is, however, the successful siblings actually weren’t the first humans to achieve flight!

The Wright Brothers Take OffWilbur and Orville Wright were born in April 1867 and August 1871 respectively, the sons of Church of the United Brethren in Christ minister Milton Wright. The brothers’ creative flair was first evident in the printing presses they developed together, but they set their sights on even loftier ambitions.

According to one brilliant story, the brothers’ ground-breaking work in the field of aviation was partially inspired by a simple toy their father had gifted them when they were boys. It was, per History, a simple paper and bamboo helicopter, “powered” by means of a rubber band. Seemingly inconsequential as the gift may have been, it reportedly sparked something in their young minds: an interest in flying machines and a drive to create their own.

Wilbur, left, and Orville Wright sit on the porch steps of their Dayton, Ohio, home in June 1909. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The outlet goes on to explain that the little helicopter had been inspired by Alphonse Pénaud, who himself was dreaming up flying machines over in France. The year was 1878, incredibly early in the history of aviation, but one thing was absolutely certain from this little story: the concept of flight did not begin with the legendary sibling duo. Not by a very long shot. They were not the first to achieve flight, either.

The Legendary Siblings’ AchievementsThe Wright Brothers’ story is certainly the most iconic and popular, though, when it comes to the topic. Their work faced all manner of challenges, but the technically and mechanically gifted brothers found ways to overcome them.

How, they wondered, to design wings that could successfully both get and stay aloft? They found the answer to this in nature: Emulate the angles at which birds hold their wings. It wasn’t until December of 1903 that one of their designs could achieve flight, and very brief flight it was: 59 seconds with Wilbur at the helm. History defines this achievement very specifically: “the first free, controlled flight of a power-driven, heavier-than-air plane.”

When considering who flew first, it’s a very important distinction. The Wrights, the outlet went on, were certainly at the forefront of aviation. Their success, then, was limited (particularly at first) by those who didn’t trust these newfangled flying machines, or perhaps didn’t see them as very practical. Much more would be needed than a demonstration of less than a minute, after all.

Historic photo of the Wright brothers’ third test glider being launched at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, on October 10, 1902. Credit: NASA on The Commons Via Wikimedia Commons.

Per NASA, the pioneering pair weren’t able to successfully take off and land back in the same location until September of 1904, in a new model of their Wright Flyer. The journey was 1 minute and 36 seconds long, which was still, while a remarkable engineering feat, far from any practical use in a wider sense. It was only the following year, with the Wright 1905 Flyer, that they succeeded in achieving sustained flight of more than a half-hour.

From there, the siblings firmly established their place in aviation history. As the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum reports, their pioneering efforts resolved some of the major conundrums that would-be pilots faced. The concept of “wing-warping” was their true masterstroke. By developing a way of adjusting the angles of the wings, they avoided the problem of lift having an uneven effect on both wings, and so on the craft itself. Sustained and stable flight of a motor-powered airplane that was heavier than air, then, was indeed first achieved by the Wright brothers.

However, there were those who flew before them, and to whom they owe a tremendous debt. Creativity breeds creativity, after all, and the brothers may never have achieved what they did without the aviation geniuses who came before them.

Earlier Flight PioneersOne such person was the German Otto Lilienthal. Born in 1848, Lilienthal’s work was a huge influence on the Wright brothers. His Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst (“Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation”), published in 1889, tackled a subject that became central to the brothers’ work: the wings and how they should be adapted.

Like the Wrights, Lilienthal was an adept mechanic. A combatant in the Franco-German war, he used his expertise to develop a flight school and tackle that very same question of how to achieve flight and what to do with the wings.

Lilienthal’s flying machines were not airplanes, but gliders. He developed around 16 of them that he personally flew over 2,000 times, tweaking and altering his brilliant designs along the way. The standard glider he created was a glorious device, complete with a tail and multi-sectioned wings which were described as being based on “the outspread pinions of a soaring bird.”

A flight of Otto Lilienthal on his artificial hill, artist’s impression. Credit: Richard Neuhauss Via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The glider, however, was a fragile confection of wood and cotton, and left its pilot incredibly vulnerable. Sadly, Lilienthal proved this himself in August of 1896, when it failed him. He died the day after from injuries sustained during a crash.

Lilienthal was, however, flying in the century before the Wright brothers did. Much further back still, the early 1500s, the legendary Leonardo Da Vinci published a study similar to Lilienthal’s. It was called Codex on the Flight of Birds, and, yet again, explored the ways in the which the wings of birds and principles behind them could be adapted to create flying machines for humans. He famously drew up a design for a flying machine, but it was never built.

Balloon Animals and Other Feats of FlightIn September of 1783, History goes on, Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier and brother Joseph-Michel sent a curious trio of animals (a sheep, rooster, and duck) on a brief expedition into the sky in one of their marvelous balloons. Later that year, two humans followed on a half-hour flight.

Nicholas Louis Robert and Jacques Alexander Charles followed just days after, in a brilliant hydrogen balloon of their own. This flight was around four times longer than that of the Montgolfiers, and firmly established 1783 as the year that people first took to the skies in powered hot-air balloons.

“Ascension de Charles et Robert, aux Tuileries, le 1er décembre 1783.”

Were these, then, the first true flights? It depends how you define the term, really, but it’s absolutely certain, again, that the Wright Brothers weren’t the first to take to the air.

Not First, but Lasting NonethelessTheir innovation was crucial is so many ways; to the United States Army for instance. The Wrights’ Flyer was contracted to the military to the tune of $30,000 (at the time) after achieving a 45 mph romp at Fort Myer in July of 1909. The army was thus in a great position to created advanced aircraft for use during the looming World War I.

Their technology, and the constant refinements it would go through at their hands and those of others, saw aviation advance at a speed that was truly remarkable. In June 1919, a little over six months after the end of the conflict, history’s first transatlantic flight was made (not by Charles Lindbergh, by the way).

The aviators who took this once-unimaginable journey were two Brits who served in the armed forces, Captain Sir John Alcock and Lieutenant Sir Arthur Whitten Brown. The iconic duo made the trip in a Vickers Vimy, a newly-developed bomber that had opened up the possibility of longer flights with its ample fuel storage. The flight from St John’s, Newfoundland, to County Galway, Ireland, took 16 hours and 28 minutes in total.

Wilbur Wright, who had died in 1912, did not live to see this aviation milestone. Though neither he nor his brother (who lived on until 1948) made this particular ground-breaking trip, their earlier efforts, and those who came before them in turn, certainly laid the foundation for it to happen.

By Chris Littlechild, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON! Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!CARTOON 12-21-2022

December 20, 2022

Colorado 8-Year-Old Becomes Youngest to Ski 7 Continents

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

While most kids are busy trading Pokémon cards and playing Roblox, eight-year-old Maddock Lipp of Golden, Colorado, has done the astonishing. Not content to stick to videogames, he’s spent his formative years exploring the world’s top ski destinations. One of his latest trips saw him skiing in Antarctica, making him the youngest person to ski on seven continents!

How did he achieve this feat? Here’s everything you need to know about Maddock’s incredible journey.

Skiing Seven ContinentsMaddock comes from a family of skiers, which has given the eight-year-old special access to the world’s top ski resorts. While he now holds the unofficial record for the youngest person to hit the slopes on seven continents, he’s not the first to break the ski record books. His sister, Keira Lipp, completed her odyssey of skiing on all the continents in February 2022.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Jordan Lipp (@daddy_kids_ski)

As for Maddock Lipp, he took to the snowy hills of Antarctica on December 1, 2022, tackling Mount Hoegh’s lower portions. This represented the culmination of ski trips worldwide accompanied by his family. He began this journey at the tender age of four and has traveled to nearly every corner of the globe.

Checking Out PenguinsApart from Antarctica, ski trips have included stops in Morocco, Chile, Italy, South Korea, Australia, and his home base of Colorado. Having seen so many different destinations in his childhood, which spot has Lipp enjoyed most? Hands-down Antarctica. He explains, “Antarctica (was my favorite) because I got to ski next to the penguins.”

Maddock Lipp, an 8-year-old boy from Golden, just possibly broke the world record for the youngest person to ski on all seven continents. https://t.co/1INFshMyBp

— Denver7 News (@DenverChannel) December 15, 2022

While traversing the world for skiing has typically ended with the seven continents, a fascinating twist may change all of that. It turns out there is a hidden eighth continent known as Zealandia. Zealandia is located in Oceania and remains 94 percent submerged beneath thousands of feet of ocean. That said, a few of the continent’s tallest mountain ranges stick above the water, including New Zealand.

One More Trip?Will seven-continent skiers use this information to break a world record by cruising the hills of the eighth continent? That remains to be seen. But when it comes to who has the most time to achieve this, Maddock Lipp holds a distinct advantage.

Fortunately, there are plenty of great places to enjoy powder in New Zealand. At the top of many skiers’ bucket lists are The Remarkables, featuring incredible alpine views and expansive runs. Other great island ski destinations include Coronet Peak in Queenstown, known for its well-groomed trails.

Will Maddock or his sister Keira become the first to conquer all eight continents? We’ll have to wait and see. But one thing’s for sure: The Lipp family has earned a well-deserved place as global skiing royalty!

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON! Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!Source: Colorado 8-Year-Old Becomes Youngest to Ski 7 Continents

CARTOON 12-20-2022

December 19, 2022

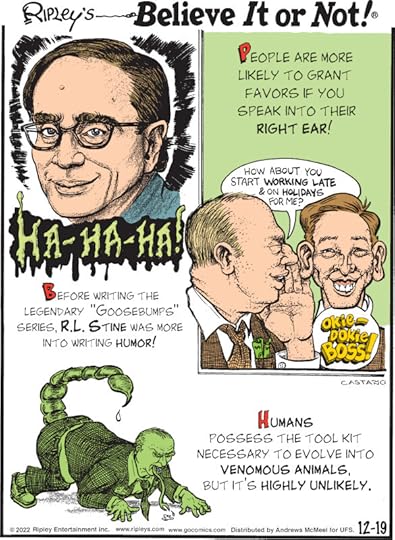

CARTOON 12-19-2022

December 18, 2022

CARTOON 12-18-2022

December 17, 2022

CARTOON 12-17-2022

December 16, 2022

Remains of Last-Known Tasmanian Tiger Found in Museum

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

The remains of the last-known Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) were recently rediscovered at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, after they were missing for over 85 years. The skeleton and skin of the four-legged creature were procured by the museum in 1936 but were unidentified until recently, according to TMAG.

What’s In a Name?Also called a thylacine, a Tasmanian tiger is actually a marsupial and part of the kangaroo family. It has been described as having a wolf-like body with stripes on the back, a possum-like tail, a foxlike face, and a belly pouch.

The last-known Tasmanian tiger died on September 7, 1936, at the Hobart Zoo (also known as Beaumaris Zoo) in Hobart. The recently discovered thylacine is not the same one that was famously photographed and filmed and billed as the last thylacine, according to researchers Robert Paddle and Kathryn Medlock. That famous thylacine was in fact the second-to-last living specimen.

Shady Origins Led to Vague RecordsPaddle, a comparative psychologist from the Australian Catholic University, says the last thylacine was a female that was caught by a trapper and sold to the Hobart Zoo in 1936. The zoo did not publicize the procurement of the animal because of the way the thylacine was trapped — ground-based snaring was illegal at the time. The thylacine only survived a few months in captivity, and its body was given to TMAG where it was stored for decades.

According to Paddle: “For years, many museum curators and researchers searched for its remains without success, as no thylacine material dating from 1936 had been recorded in the zoological collection, and so it was assumed its body had been discarded.”

At this stage, thylacines were already known to be rare – but they would not be declared extinct until 1986. Part of the specimen was prepared as a flat skin that showed off the thylacine’s iconic tiger-like stripes. 3/6 pic.twitter.com/QHjIvF0HZb

— TMAG (@tasmuseum) December 7, 2022

Medlock, Honorary Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at TMAG, explained that an unpublished 1936/37 report by taxidermist William Cunningham verified the arrival of the last thylacine at TMAG. Researchers then reexamined all thylacine skins and skeletons in the collection and discovered one in the museum’s education department.

The body of this thylacine was skinned, and its skeleton was divided in a manner that would have allowed museum science teacher AWG Powell to share its anatomy with pupils. The taxidermist had prepared the skin so it would be portable and used as an educational tool.

Using real specimens allows museum visitors to get first-hand experience with native wildlife, and in 1937 classes were delivered to some 7,650 children at @tasmuseum. Past generations of children patting her soft fur may explain the wear on the last thylacine’s forehead. 4/6 pic.twitter.com/xuMnb5V0N8

— TMAG (@tasmuseum) December 7, 2022

TMAG Director Mary Mulcahy called the discovery of the remains “bittersweet.” She explained, “Our thylacine collection at TMAG is very precious and is held in high regard by researchers, with the museum regularly receiving requests to access our mounted specimens as well as thylacine bones, skins, and preserved pouch young.”

The remains of the last thylacine are currently on display alongside two other extinct species: the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet.

A Possible Future for the ThylacineAccording to NPR, the thylacine species met its end after the Australian government promoted hunting in order to protect cattle. Researchers have also found that a lack of genetic diversity may have played a role in its extinction.

However, it’s possible that people in the future may have a chance to see a resurrected Tasmanian tiger. Earlier this year, we covered the news of a research group successfully mapping the DNA of the thylacine’s closest living relative — a numbat. Such information could be used to give the extinct mammal a second chance to roam the Earth.

By Noelle Talmon, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON! Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!Source: Remains of Last-Known Tasmanian Tiger Found in Museum

CARTOON 12-16-2022

December 15, 2022

Earth’s Missing Continent That Took 375 Years to Find

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Some knowledge remains static, while other so-called facts become footnotes in history. For example, the nine planets many of us grew up learning about in school became a mere eight in 2006 because scientists redefined the term “planet.” After the update, poor Pluto got unceremoniously resigned to the “dwarf planet” bin.

Of course, places like Pluto are really far away (between 2.66 and 4.67 billion miles, depending on its elliptical orbit position). Understandably, scientists are still working to fill knowledge gaps exacerbated by distance. But while you might assume we have things fleshed out on Planet Earth, it’s time to think again.

As it turns out, our planet boasts eight continents rather than the seven you learned about as a kid. Keep reading for the full scoop on why it took scientists nearly four centuries to discover this missing continent and what it means for geography.

A 375-Year-Old Scavenger HuntTwo things stick out when it comes to the hunt for the eighth continent. First, people have talked about it since at least ancient Roman times. Second, it was under our noses all along.

So, what was the hold up? For starters, nobody looked for the mythic Terra Australis until the 17th century. That’s when Abel Tasman set out with a crew of vagabonds who eventually reached the New Zealand coast. There, they had a fatal run-in with the Māori, who sent them packing, never to return.

Abel Janszoon Tasman. Credit: Archives New Zealand Via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The hope of finding a fabled and expansive chunk of land in the southern hemisphere didn’t die with Tasman and his ragtag sailors, though. Other explorers, including Captain James Cook of Great Britain, launched quests to locate it, but to no avail. By the late 19th century, Sir James Hector of Scotland rekindled the mystery after studying an archipelago off the coast of New Zealand.

A Great Continental AreaIn 1895, Hector published a paper with the Royal Society of New Zealand about his findings. In the article, he argued that New Zealand appeared to be “the remnant of a mountain-chain that formed the crest of a great continental area that stretched far to the south and east, and which is now submerged.” Although he made a compelling case for an undiscovered continent, Hector’s findings fell on deaf ears. And most researchers wouldn’t take the concept seriously again for centuries.

James Hector, Scottish-born medical doctor (M.D.), geologist, explorer, head of New Zealand Institute, Geological Survey of New Zealand, and Chancellor of the University of New Zealand.

Then, in 2017, a group of researchers boldly announced the discovery of the eighth continent, complete with a name reminiscent of a Ben Stiller movie: Zealandia. But the bombshell dropping didn’t stop there.

The scientists, including Andy Tulloch of the New Zealand Crown Research Institute, declared the continent 1.89 million square miles in size. (That’s about half the size of Australia.) Yet, despite this scale, the microcontinent has historically been easy to miss because approximately 94 percent of it remains buried beneath 6,560 feet of water.

The Smoking GunHow did scientists conclude Zealandia is, in fact, another continent? Like the swap from nine planets to eight, discovering Zealandia started with redefining the word “continent.” This redefinition effort happened in the 1960s, resulting in criteria like:

A wide variety of rocksA high elevationA thick crustA massive sizeIn all four cases, Zealandia fit the bill. Yet, no public announcement followed. Three decades later, Bruce Luyendyk, an American scientist, decided to give it another go. He declared the sunken continent Zealandia, making a case for its inclusion in textbooks. But more time passed before people started seriously considering any revisions. Ultimately, it took a fascinating feat of politics to motivate further study of the legendary southern continent.

In the 1990s, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea motivated New Zealanders to get to the bottom of the continental mystery. The convention gave nations the right to claim up to 200 nautical miles of territory beyond their Exclusive Economic Zones. That’s when the light bulb went off for New Zealanders: If the island nation could prove it was part of an enormous continent, it could add nearly six times more territory to its sovereign footprint!

Scientific Data Clinched ItA hardscrabble attempt by New Zealand to make its case followed. This involved funding various scientific expeditions to gather data, from rock samples to satellite images and measurements of the crust’s thickness. The final verdict? Yes, Virginia, there is an eighth continent.

New Zealand unlocked one of the most extensive maritime territories on Earth. All told, Zealandia comprises everything from New Zealand to Lord Howe Island, Ball’s Pyramid, and New Caledonia. As for how Zealandia fits into the larger geologic picture, that’s also a compelling story.

Scientists now hypothesize that Zealandia once comprised a portion of Gondwana, an ancient supercontinent that included all the land of the southern hemisphere. While researchers still have a lot to learn about Zealandia and its many mysteries, one thing’s for certain: This submerged continent has rewritten the facts about terrestrial land masses.

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON! Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!Source: Earth’s Missing Continent That Took 375 Years to Find

Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog

- Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s profile

- 52 followers