Philip Sandifer's Blog, page 6

August 4, 2020

Leave It Open

The first song to have a demo completed for The Dreaming (“Sat In Your Lap” was initially released as a standalone single), “Leave It Open” introduces much of the album’s ambition and cadences. Another treatise on the nature of thought and repression, Bush develops and inverts her previous metaphysical ideas about the world, presenting it as a frightening and hostile sphere yet treating interaction with it as an inevitability, and even a relationship where a person’s interiority can have input. As the refrain stipulates with a degree of bellicosity, “harm is in us, but power to arm.” In “Leave It Open,” Bush creates an ethos of wondrous fear, where allowing the self to become a vessel for something Other is an act of submissive reclamation of human potential.

Let’s start counterintuitively (in the spirit of The Dreaming) with the coda of “Leave It Open”, which sees Bush proffering a rare, aphoristic thesis statement in the form of a repetitive double-backmasked chant: “we let the weirdness in.” Amusingly, upon release this was Bush’s most controversial coda, with listeners calling into Bush’s television and radio interviews attempting to guess what distorted words Bush is singing (“we paint the penguins pink” is the best one). “We let the weirdness in” sounds unlikely — it’s disjointed, with abstractions and syntactic ambiguity. As my friend Rohanne points out on the brilliant Kate Bush podcast Strange Phenomena, The Dreaming sees Bush shifting from writing character narratives to reorienting her songwriting around concepts and abstractions. What is “the weirdness?” And how are we letting it in? “Leave It Open” concludes on a note of imprecision and unknowability. But the song also begins there — the verses and refrains are similarly disjointed in their grammar: “with my ego in my gut/my babbling mouth would wash it up.” The clauses are unclear in their relationship to their object and subject, phrasing abstractions in a way that suggests they’re corporeal stimuli. “Wide eyes would clean and dust/things that decay, things that rust” suggests bodily fluidity. The aversion to coherent speech and language is almost Burroughsian: language is a virus, and can only be allowed through in a broken, primal form, taking after a rhythm track. The Dreaming’s incipient nucleus of uncertainty creeps forth.

Moreso than “Sat In Your Lap,” “Leave It Open” emphasizes a theme that pervades The Dreaming in its exploration of madness as a feminist liberation. It sees Bush unharnessing herself from the tyranny of rational thought and conventional speech in favor of “letting the weirdness in.” An infusion takes place, with the song mostly looking at forms of opening and closing (“my door was never locked/until one day a trigger come cocking”). “Leave It Open” describes physically allowing unknowable things into one’s mind and body. Bush’s vocals are an entourage of different voices, with her lead vocal a tremulous inhalation (“watched it weeping/but I made it stay”), and her B.V.’s a series of childlike, high-soprano shouts (“but now I’ve started learning how!”). She uses extreme parts of her vocal range, the muscular and traditionally masculine “deep” end, and the (allegedly) feminine voice she’s often caricatured as having. There’s no single, definitive “Kate Bush voice” at work in this, nor a traditional idea of how women in pop music are supposed to sound. As Bushologist Deborah Withers writes, “becoming is an empathetic, expansive act and pivots on issues of receptivity and interconnectivity.” In the verses, Bush sounds afraid to breathe. “With my ego in my gut” even suggests the holding of breath (quite a departure from two songs ago), as the first verse describes a fear of unleashing one’s psyche on the world: “my door was never locked,” “wide eyes would clean and dust,” a series of declarations each ending in “I keep it… shut.” You can’t harm me, she says. I’m not saying a word.

“Leave It Open” flaunts its abnormality, from its weird syntax to its mix mostly consisting of heavily processed vocals, a booming rhythm section, and a rather agonized guitar part even by Alan Murphy’s standards. Once again, it’s built around its primal 4/4 drumbeat (somewhat reminiscent of Queen’s “We Will Rock You”), mostly locked into Preston Heyman’s shells. Bush’s vocal clearly tracks it, as her emphasis continually meets the downbeat (“WITH my ego IN my gut…”). Even the piano is a percussive instrument here, offering stabbed chords mostly to accentuate the drums, sticking to a narrow and mostly conventional chord progression in G minor, i-V-IV-VI (although it’s not without Bush’s chromatic flare — she plays D and C, the respective V and IV degrees of G melodic minor, and end the progression on Eb, the VI of G natural and harmonic minor).

The results are both claustrophobic and resounding, hemming itself in to create an atmosphere of confrontational release. A purging happens: rather than knowledge being something that you never have, Bush allows it to seep in on its own time, declaring throughout the second verse “I leave it open.” The body becomes a kind of tap for outside forces and radical change, letting them through with patience and silence. Queer people might relate to “Leave It Open’s” description of keeping the closet shut, and letting the exponential strangeness of their minds and the world harmonize. At once, the body stops tensing and so does the mind, letting the unknown pour through (“narrow mind would persecute it/die a little to get through it”). Despite being more intense and discordant than “Sat In Your Lap,” “Leave It Open” is weirdly anthemic and optimistic: allowing the weirdness is a way to discover new ways of being. Rigidity gives way to tranquility. Maybe the weirdness is the crack in everything, as Leonard Cohen once said. It’s how the light gets in.

Bodily inertia has been a focal point of these last few songs — even “Army Dreamers” is about death and loss. Specifically, bodies become inert as a form of self-defense. “Leave It Open” offers an alternative: perhaps it’s OK to let the body rest and allow outside forces through; “I kept it in a cage/watched it weeping/but I made it stay,” as if the body is a vessel for the mind and the things external to it. Bush touched on this idea in a newsletter at the time, writing “like cups [what is it with The Dreaming and cups?], we are filled up with feelings, emotions — breathing in, breathing out. The song is about being open and shut to stimuli at the right times. Often times we have closed minds and open mouths when we should have open minds and shut mouths.” One wonders if Bush has ever encountered meditation or contemplative spiritual practices, as this is pretty much the same premise. It’s also the crux of dissociation, the psychological reaction where the brain shuts down to protect itself from triggers. There’s a reason the brain is both able to shut down and be alert — varying defense mechanisms react to different stimuli.

Bush is far from alone in her treatment of women’s creativity as a psychological flood. The 1970s had been populated by such literature, including French feminist writer Hélène Cixous’ classic 1975 essay “The Laugh of the Medusa.” In the essay, functionally an artistic feminist manifesto, Cixous expounds on the trauma inherent in women’s subdued role in patriarchal history, calling for women to “put [themselves] into the text — as into the world and into history — by her own movement.” She frames writing as a radical act that gets performed in private (not dissimilar to the crux of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own), serving as a reclamation of history and a subversion of the Western canon, treating the true capabilities of women as “luminous torrents,” and at once point shockingly paralleling “Sat In Your Lap” with the declaration “I too, overflow.” Most striking is the way “The Laugh of the Medusa” frames women’s liberation as a way of dealing with trauma; that unleashing one’s self into the world is the way to combat misogynistic suppression. History is made of women’s silence and private lives, she argues: “A world of searching, the elaboration of a knowledge, on the basis of a systematic experimentation with the bodily functions, a passionate and precise interrogation of [one’s] erogeneity.” Most tellingly, she observes that women have been made to think of their own femininity as monstrous and fight it in the finite but immense arena of the mind.

The self-proclaimed non-feminist Kate Bush taps into this idea aptly. She may not think her ideas are feminist (and indeed, they often aren’t), but the number of liberationist feminist missives she inadvertently pens over the years are countless. As Cixous declares “we have been turned away from our bodies,” Bush turns the body inside out. She suggests a new mode of being, allowing whatever may come into one’s presence to fill a person up. It’s not quite an act of expulsion, but nonetheless “Leave It Open” prescribes a sort of bodily tranquility, allowing one’s body to welcome the world and quit shutting it out. Perhaps this exposure to the Other will allow us to unleash ourselves on the world more fully. Trauma and queerness will not be silent. They will rend the ether. We’ll let the weirdness in, but afterwards the weirdness is going to need serious therapy.

Backing tracks laid down at Townhouse Studios, Shepherd’s Bush, London in May ’81. Overdubs recorded at Odyssey Studios, London in August ’81, and at Advision Studios, Fitzrovia, London from January through March ’81. Mixed at Advision from March through May ’81. Released on The Dreaming on 13 September ’82. Personnel: Kate Bush — vocals, piano, Fairlight. Preston Heyman — drums. Jimmy Bain — bass. Alan Murphy — electric guitar. Ian Bairnson — acoustic guitar. Hugh Padgham — engineering. Image: Sheryl Lee as the late Laura Palmer experiencing a beatific (?) vision in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992, dir. David Lynch/D.O.P. Ron Garcia.)

August 1, 2020

TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8 Kickstarter

At long and wearied last, it's time for the Kickstarter for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8, covering the Paul McGann and Christopher Eccleston eras of the series. The Kickstarter is over here waiting to accept your money. The base goal is a somewhat higher than before $5000, largely because I've learned my lesson about shipping physical rewards. Also, there's a lot fewer physical rewards. But all of this is technical shop talk, and this should be about publicity, so let me change hats and be a proper hype woman for myself.

At long and wearied last, it's time for the Kickstarter for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8, covering the Paul McGann and Christopher Eccleston eras of the series. The Kickstarter is over here waiting to accept your money. The base goal is a somewhat higher than before $5000, largely because I've learned my lesson about shipping physical rewards. Also, there's a lot fewer physical rewards. But all of this is technical shop talk, and this should be about publicity, so let me change hats and be a proper hype woman for myself.

This book will cover the two attempts to bring Doctor Who back—the ultimately disastrous US revival in 1996, and the massively successful UK one in 2005. It begins with a lot of hope and ends with a lot of hope, and everything in the middle is one of the most gloriously tangled messes in the history of the series, comprising multiple irreconciliable timelines, feuding lines, and a lot of very, very daft shit. If Volume 7 is a story about how to get cancelled and still be a triumph, Volume 8 is a story about how to score an absolutely massive and medium-changing hit television show despite doing literally everything wrong for nearly a decade.

And yet in that tangled web of errors there's so much that's fascinating. Works by Kate Orman, Jon Blum, Paul Magrs, Lloyd Rose, and Lawrence Miles abound. Paul McGann's consistently deft performance that somehow works even when he's sleepwalking through some of the most dire scripts Big Finish has ever written. And just a staggering amount of stuff that is so brain-meltingly weird that you wonder how on Earth anybody thought this was what you should do with Doctor Who.

As it stands, the book should include almost all of the blog posts from the McGann and Eccleston eras. (As with McCoy, there's a few that were frankly filler to deal with the fact that three novels a week was an unsustainable pace, and I'm likely to cut those.) And then, with stretch goals, there are several more. The stretch goals are roughly organized in phases, proceeding thusly.

Through $7000, they add the Now My Doctor essays that sum up the respective eras of the television show. No Eruditorum Kickstarter has ever failed to hit this sort of tier, and I can't imagine it's going to be a problem this time. It'd be bizarre not to have these.

Starting at $8000 are a triptych of essays about the War Doctor era. Due to my continuing refusal to write new essays on Big Finish material, these will consist of a Day of the Doctor essay (almost certainly working in the novel this time), an essay on the book Engines of War, and a Now My Doctor essay. (Might I slip in an essay on the Eleventh Doctor comics run dealing with the War Doctor? No active plans to, but you never know.)

At $11,000, we get to the canon essays. These are big and fun. How Many Time Wars Were There? Does the Eighth Doctor have a Chronology? So Was He Half Human? All of these questions will be delved into with thoroughness and a love of knocking over tables and making a mess. These are consistently some of my favorite essays to write in the books, and I'm really hoping we get all three.

$14,000 is an odd duck—a Pop Between Realities essay on Spiceworld, the Spice Girls film, and more broadly on New Labour. This is a bit of scene setting I missed doing the blog, and it really needs unpacking, so I'm hoping we can get this in there.

And finaly, at $15k and $16k, a pair of novels I'd like to add in: Lloyd Rose's acclaimed City of the Dead, and the Faction Paradox classic Book of the War.

All of these, I think, are fun essays that I actually want to write. So hopefully we'll plow through a good chunk of stretch goals and get to fill out the book with all sorts of goodies.

This was a weird era to write about, but it has some of my favorite writing in Eruditorum, especially the Eccleston season, which has multiple mad, gonzo essays, including two that are going to be glorious nightmares to try to format for print. I am thoroughly excited to clean them up and get them into an Official Version, and to finally bring the TARDIS Eruditorum books into the new series.

So if this is something you want to read, and if you want to financially support my work, I implore you to go back the Kickstarter. Once again, the link is right here. Thank you, as ever, for your support.

July 31, 2020

IDSG Ep60 - Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying

This week, Daniel and Jack discuss Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying, two alumni of the Intellectual Dark Web, their 'origin story' as 'public intellectuals' in the Evergreen College kerfuffle of 2017, and their current views on Black Lives Matter and Trans Rights as expressed in their Dark Horse podcast. Jack gets angry and giggly.

Next week, we will move on to Bret's brother Eric Weinstein.

Content Warning.

Permalink / Direct Download / Soundcloud

Bari Weiss, "Meet the Renegades of the Intellectual Dark Web." https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/08/opinion/intellectual-dark-web.html

Bret Weinstein homepage: https://bretweinstein.net/

Heather Heying homepage: https://heatherheying.com/

Evergreen State College at Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evergreen_State_College

Programs and Courses at Evergreen. https://www.evergreen.edu/academics/programs

Bret Weinstein Explains the Day of Absence on Joe Rogan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-st73zhZL3A

Bret Weinstein on Tucker Carlson, May 26 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_j9nFced_eo

Jacqueline Littleton, "The Truth About the Evergreen Protests." https://medium.com/@princessofthefaeries666/the-truth-about-the-evergreen-protests-444c86ee6307

Noah Berlatsky, "The Real Free Speech Story at Evergreen College." https://psmag.com/education/the-real-free-speech-story-at-evergreen-college

"Another Side of the Evergreen State College Story." https://www.huffpost.com/entry/evergreen-state-college-another-side_b_598cd293e4b090964295e8fc?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAEpQrgKs2MwkdM5iym8soDVnkkpQYbq3YKgw6fp62JA2xw_v_vSfS_O1EkcMNbbaM_leOCssfRJspZ8CiodkDerxlEWdw5vx3Vdmoe-2UFbmTkYSkhEMWWDMBaa_48LFSb6BMWtFz2X1xbCSS51b_fYIFe27hfLdLeFCj232fAlS

Nancy Koppelman, "Bret Weinstein's Second Act." https://medium.com/@nancykoppelman/bret-weinsteins-second-act-from-liberal-arts-professor-to-public-intellectual-88471fdb2518

"The Intellectual Dark Web Goes to Washington." https://theoutline.com/post/4717/the-intellectual-dark-web-goes-to-washington?zd=1&zi=ft4wuqma

The Dark Horse Podcast: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCi5N_uAqApEUIlg32QzkPlg

"Overlooked No More: Valerie Solanas, Radical Feminist Who Shot Andy Warhol." https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/obituaries/valerie-solanas-overlooked.html

William Simon U'Ren Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Simon_U%27Ren

William Simon U'Ren Plaque in Oregon City: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Simon_U%27Ren

Mariame Kaba, "Yes We Mean Literally Abolish the Police." https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/opinion/sunday/floyd-abolish-defund-police.html

For fun:

Majority Report, 19th July 2020, ‘Weinstein Bro Politely Calls Dave Rubin a Paid Shill’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4uSlbqSXVA

Potholer54, ‘Did Covid-19 Start in a Chinese Lab?’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ab-r0capbzk

July 27, 2020

Sat In Your Lap

We did it. I hit $300 on the Patreon because of your support. Thank you so much to everyone who pledged (all 98 of you),  shared the link, contributed to reaching the goals, or was just kind and supportive. This is quite literally life-changing for me. I can making a living off my passion without having to compromise financial security or my mental health. You people are amazing and I am indebted to you all. To be clear, $300 is a minimum though. I'm a disabled trans woman, and people will inevitably drop their pledges. Continued support would be great. But in the meantime, thank you. My life is better for your support.

shared the link, contributed to reaching the goals, or was just kind and supportive. This is quite literally life-changing for me. I can making a living off my passion without having to compromise financial security or my mental health. You people are amazing and I am indebted to you all. To be clear, $300 is a minimum though. I'm a disabled trans woman, and people will inevitably drop their pledges. Continued support would be great. But in the meantime, thank you. My life is better for your support.

Demo

Sat In Your Lap (single)

Sat In Your Lap (LP version)

MV

Dance rehearsal (fragment, Looking Good Feeling Fit)

The aftermath of Never for Ever was a period of burnout for Bush. Prone to depressive burnouts after the completion of projects, she found herself drifting into a nadir of fruitless ennui, which she deemed “the anti-climax after all the work.” Completing Never for Ever in May 1980, Bush, not for the last time, put significant space between herself and the public, taking a holiday after an exhausting several months of recording. By the time Never for Ever was released in September, Bush was only just recovering from her creative inertia. Her timing was auspicious, as Never for Ever not only became her first #1 LP in the UK but the country’s first ever #1 studio album by a female solo artist ever. Never for Ever’s success was accompanied by heaps of promotion by Bush, including the usual run of performing songs on talk shows as well as signing albums for hundreds of fans at a time. Now she had more creative agency than she had previously, touting Never for Ever as “the first [album] [she] could hand to people with a smile.” Kate Bush the prodigy who sang “Wuthering Heights” was already a distant memory, transforming into Kate Bush the great 1980s British songwriter.

Yet Bush’s listlessness and struggle to write songs persisted for some time. It’s not hard to see why — the stress of Never for Ever’s production and the attention of the British public would be enough to put a damper on anyone’s creative output. It took seeing other musicians at work to get her motivated again. In September, Bush and her boyfriend Del Palmer attended a Stevie Wonder concert at Wembley Arena. Wonder was in a period of creative renewal himself. Having recently turned out a rare Motown flop in the distinctively titled Journey Through “the Secret Life of Plants”, he’d rebuilt confidence with his delightful Hotter than July LP. The concert broke Bush out of her writer’s block — “inspired by the feeling of his music,” as she later wrote, Bush got back to work on her songs, and forged a path towards her next album.

Bush’s work to date was largely harmonic, built around what notes went together interestingly on the piano. Rhythm was secondary for her: it’s hard to think of a rhythmically powerful song on Bush’s first three albums. Her preparations for Kate Bush IV had thus far consisted of little bits of melody, but without a focal center. After the Wonder concert, she realized she needed to start her songwriting from the rhythm track upwards. At home, she programmed a rhythm into her Roland drum machine (according to my friend Marlo, the Roland on her demo from the period sounds like a CR-78, and woe to anyone who disagrees with Marlo on drum machines), and “worked in [a] piano riff to the hi-hat and snare.” A demo resulted: “Sat In Your Lap,” Kate Bush’s first solo production, was in its nascency.

“Sat In Your Lap” wasn’t always Bush’s first self-produced song. For a time, she entertained bringing in experienced producers, including long-standing David Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti, going so far as to spend a day in the studio with him. The collaboration went nowhere, and Visconti has grossly remarked “all I can remember is the Bush bum.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bush decided to take on the producer role herself, with the intensive collaboration of a series of engineers. The first set of sessions for the album that would be The Dreaming were staged at Townhouse Studios in May 1981. Her collaborating engineer was Hugh Padgham, a producer for Phil Collins and XTC known for the “gated drum” sound that would define 80s pop (compress the drums, use a recording console’s “gate” to remove their reverb, resulting in a kind of sound vacuum. See Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight”). Bush and Padgham’s time in Townhouse was productive yet short-lived. Padgham is rare among Bush collaborators in having negative feelings about working with her, grumbling about her tendency to overpack a mix and experiment rather than having a concrete, straightforward vision. After laying backing tracks for three songs, Padgham moved on, dissatisfied with his latest gig but having indelibly marked the sound of The Dreaming.

Bush’s ad-libs, piano riffs, and rhythm track came together quickly in the studio, quicker than any other song on The Dreaming. Having a drum-centric engineer like Padgham was incredibly useful for her, as the early recording of Bush’s rhythm track showed. “Sat In Your Lap” is heavily percussive, built around its drum sound and brass section (initially synthesized on a Yamaha CS-80). The partially syncopated drumbeat (“dum-DUM-dum-DUM”) is Preston Heyman’s most memorable to date, a fine translation of the demo. The frantic, almost pharyngeal rhythm track has a kick drum so guttural and suppressed (though not apparently gated) that it can easily be mistaken for one of Bush’s vocal onomatopoeias. The track’s sonic menagerie (Bush’s recurring motif of musical instruments as bodily extensions lives to a maniacal extent), a veritable ensemble of screams, tinny horns on the Fairlight CMI, swishing bamboo sticks (thanks to Paddy Bush and Preston Heyman) childlike whispers, “HO-HO-HO’s,” and bellows of “JUST when I think I’m king!”

What better to bring Bush out of a period of creative stagnation than a missive to psychological stagnation? Or even better, a tremendously loud, busy, and clamorous one. Amidst the song’s sheer volume is a narrative of inertia and stillness. Bush deploys a childlike whisper in the verses, a canny juxtaposition with the rhythm track’s masculine percussiveness, indicating juvenile trepidation as she watches adults go about their lives: “I see the people working/I see it working for them/and so I want to join them/but then I find it hurts me.” The verses are terse observations from an unmoving figure, grounded in a desire to catch up and have a powerful mind: “I see the people happy/so can it happen for me?,” “I want to be a lawyer/I want to be a scholar/but I really can’t be bothered,” “I want the answers quickly/but I don’t have no energy.”

The verses are similarly sclerotic, sticking to its home key and mode of Ab Dorian closely, with an incessant chord progression of i-VII (Abm7-Gb), a relatively conservative doublet of chords that seem paranoid about wandering away from the key’s tonic (limiting a verse to its key’s tonic and subtonic is uncharacteristically parsimonious for Bush), and even staying in 3/4 the whole time. The refrain sees a return to Bush’s harmonic and rhythmic weirdness. Her predilection for following up a key’s tonic chord with the tonic of the parallel key lives as ever, as she maneuvers from Ab minor’s IV chord (Db) to Ab major’s iv (Db minor). The refrain otherwise sticks to a fairly conventional Ab minor (IV-iv-i-IV), with a smattering of Bushian time signature changes (it mostly sticks to 4/4, with a bar in 2/4 at the tail end of “some say that knowledge is something sat/in your lap” and “ho, ho, ho”). The post-chorus breaks with Ab Dorian, modulating to Db Mixolydian (a major key alternative to Dorian mode) with “JUST when I think I’m KING!”, dallying with chords not present in the key (A) and owning its unified disjointedness.

“Sat In Your Lap” conveys both frantic motivation and fearful inaction — it is enticed by the busy and productive activities of people and intimidated by the energy exerted in them, perhaps suggesting a character outwardly compelled to be a productive adult too soon (it’s possible Bush could relate). It is at once rapid, careening at 146 BPM, and petrified with fear. The music video (Bush’s first without director Keef Macmillan) swerves between stillness and freneticism. During the verses, Bush is mostly seated in a white dress, while the refrains see her cavorting with dancers in dunce caps. Former “gifted and talented” children drained by adults’ external compulsion to excel may encounter a kindred spirit in “Sat In Your Lap.” Yet even in its inertia lays a search — despite the emotional shutting down, the desperate need for knowledge and truth is genuine and constant.

The incessant refrain, consisting of Bush screaming (with occasional variations) “some say that knowledge is something sat in your lap/some say that knowledge is something that you never have,” makes the preoccupation with knowledge clear. Holy shit, says Bush, look at all this cool stuff adults do! And all these neat religious and philosophical paths! “Some say that heaven is hell/some say that hell is heaven!” Is anyone right? The sheer quantity of faiths can be incredibly disorienting to an adult. The comparable power that spirituality can have over a child is often formative.

Spirituality often works at a snail’s pace. Things that become deeply engrained in a young believer’s mind at an early age will only become clear to them several years later. A child confronted with gods can have a variety of emotional responses: indifference, awe, fear, befuddlement, joy. Sometimes a child is deeply moved by what they witness and feel. Yet with that, there can be complete physical inertia — shock and over-saturation, or interior silence and contemplation. For instance, the Hebrew Bible’s prophet Ezekiel responds to his first apocalyptic vision by sinking into days of catatonia. Bush’s answer to the mind-body problem is a symbiotic one — it’s an ouroboros, with no strict origin point, the body and the mind depending on one another. Once “Sat In Your Lap” taps into this idea of

Complicating this is the partial secularity of the song’s search. Her questions aren’t any less spiritual for it — some of the most spiritually complex people I’ve ever met are confirmed atheists, and Kate “I don’t think I’ve really found a niche” Bush hardly seems like a Bertrand Russell-esque non-believer. Ever the aesthete, Bush claims that she’s primarily drawn to the iconography of faith: “such powerful, beautiful, passionate images!” as she said of her Roman Catholic upbringing. Her first ever published writing was a poem about the Crucifixion. In a 1979 interview, she prodded a possible belief in a God, opining that God was “a label for people to put all their belief and love into,” and that putting such emotional effort into one’s relationships with people causes one to “reach an aim.” For all the theological crudeness of this idea (it boils down to little more than a hippie’s plea for everyone to just get along), Bush is (characteristically) unintentionally right. There’s a deep emotional center to faith and prayer. Contemplative and meditative traditions are built on unifying one’s emotional state with spirituality. This doesn’t make the experiences any less real — feelings are facts of life. An empirical understanding of any societal phenomena has to grasp its emotional basis: the values and emotions it appeals to.

Another animating tension of “Sat in Your Lap” is its emotional fluidity while nominally discussing knowledge: “some say that knowledge is something sat in your lap,” or knowledge is “something that you never have.” These are largely apophatic definitions of knowledge, defining it as an elusive force. The rampant emotiveness pervades a search for knowledge. “In my dome of ivory/a home of activity/I want the answers quickly/but I don’t have no energy” sees a desire for knowledge colliding with aporia and sensory overload. Without a clear path forward, sometimes the only trajectory is acceleration and exhaustion.

As the only answer to the unanswerable is sublime incoherence, the song’s coda is hermetic descent into sensory overload. Iconography blurs (“Tibet or Jeddah,” “to Salisbury/a monastery”) in a tendency that’s strong in the last couple verses, as Bush inverts Psalm 23 (“my cup, she never overfloweth”), dabbles in desert-dwelling, monasticism, cathedrals, and with “some grey and white matter,” the human brain (grey and white matter oversee the brain’s connection to the spinal cord). “Sat in Your Lap” concludes with inconclusiveness: its dance is in the terrifying glory of befuddlement. Asceticism is a cerebral process as well as physical: the brain responds to the body’s state. Bush is engaging with some genuinely fascinating systems of thought here: for all the approaches to the mind/body problem that have been formulated, responding to it with “isn’t scholastically-caused sensory overload a kind of asceticism?” is new.

Recorded at Townhouse Studio 2, Shepherd’s Bush in May 1981; mixed through June. Issued as a single 21 June 1981; released again as the opening track of The Dreaming on 13 September 1982, over a year later. Music video also released in July ’81. Like every other song on the album, never performed live. Kate Bush — vocals, piano, CMI, production. Hugh Padgham — engineer. Nick Launay — engineer (mixing). Preston Heyman — drums, bamboo sticks. Jimmy Bain — bass. Paddy Bush — backing vocals, bamboo sticks. Ian Bairnson — backing vocals. Gary Hurst — backing vocals. Stewart Avon-Arnold — backing vocals. Geoff Downes — CMI trumpets. Photo: Kindlight.

July 23, 2020

Of Human Bondage Ep. 1: Dr. No & Patreon Update

Hi all! I want to start this post with a quick update regarding the Patreon. The outpouring of support from friends and readers  has been truly astounding. I cannot describe the thrill of waking up yesterday and realizing I would soon be able to live off my writing. The support of my community, the chance to fully dedicate myself to my craft, and not having to resort to a re-traumatizing job in order to survive makes for a tremendous feeling of support and gratitude. I cannot thank you all enough. You are amazing and have literally, materially changed my life.

has been truly astounding. I cannot describe the thrill of waking up yesterday and realizing I would soon be able to live off my writing. The support of my community, the chance to fully dedicate myself to my craft, and not having to resort to a re-traumatizing job in order to survive makes for a tremendous feeling of support and gratitude. I cannot thank you all enough. You are amazing and have literally, materially changed my life.

Yet we musn't declare victory too early. $300 is the goal at which I'll feel safe living off Patreon, and at time of writing we're just $17 short of that. Lots of folks have stepped in to get me to the $300 mark with promises to undertake various projects. Here are some things that will happen if I hit $300 on Patreon:

El will review Revolution of the Daleks. This is the only way she will do so.

Jack will write about the Big Finish audio Brotherhood of the Daleks, featuring the Doctor's ties to Karl Marx. Yes, really.

My dear friend Will Shaw, author of the Black Archives book on The Rings of Akhaten and New Atheism, will write an undoubtedly delightful missive on the terminally execrable Sam Harris.

James Wylder will write queer monster stuff! With spiders!

Several other people have made offers I can't recall off the top of my head, so let's go with "& more!"

I literally cannot overstate how much getting to this tier would mean to me or how delightful any one of these little projects would be. So please back, or you can't back, share the link. This is already putting me on a path to stability.

In other exciting news, you can now listen to Of Human Bondage, the podcast where Kit Power, Sam Maleski, and myself discuss the James Bond movies of Eon Produtions. It's an unusual Bond project, in that none of us are terribly sympathetic or reverential about our source material (what do you think we are, firing squad fodder?). Yet we retain a strange fascination with James Bond, having intelligent and riotously funny conversations about the pathologies and psychosexual weirdness of upper-class British white men that these films and Ian Fleming's novels serve as a lens towards. It's one of the most fun and cathartic projects I've ever engaged in, and feedback so far has been positive. Check it out. It's a good time.

And thank you, everyone.

July 22, 2020

IDSG Ep59 The Heimbach Maneuvre / News Roundup

In this bumper episode, Daniel tells Jack all about the recent response to us by Matt Heimbach and Jesse Morton on their Walk on the Right Side podcast. Also, we do a news roundup, taking in Camilla Long, Lauren Southern, Andrew Neil, Ben Shapiro, Tim Pool and Hank Hill; Tucker Carlson and his writer Blake Neff, recently revealed as a racist forum poster; the arrest of Steven Baca; and the latest scary developments in Portland as ICE/DHS start black-bagging protestors, featuring the rise to instant fame of Tazerface. Also... the triumphant return of Cantwell News.

Content Warnings Apply.

Permalink / Direct Download / Soundcloud

Notes/Links:

Cantwell's additional charges. https://www.fosters.com/news/20200714/jailed-white-nationalist-from-nh-faces-more-charges

Blake Neff exposed: https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/10/media/tucker-carlson-writer-blake-neff/index.html

Tazerface16 assulted. https://twitter.com/PDXzane/status/1285037835058180097?s=20

Tazerface aka "Chris David" describes the assault: https://twitter.com/chadloder/status/1284999020188807168?s=20

Chad Loder thread on ABQ militia shooting: https://twitter.com/chadloder/status/1272715820938850304?s=20

Steven Baca arrest: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/16/albuquerque-militia-shooting-protest/

Take a Walk on the Right Side Episode 6. https://anchor.fm/take-a-walk-on-the-right-side/episodes/Episode-6-Pandemic--Protests-and-Reciprocal-Radicalization-Gone-Wild-egk0ah/a-a2m68bt

Also, sorry about forgetting to announce the last episode here. Here's a link to Episode 58, Transphobia and The Right Stuff: https://idontspeakgerman.libsyn.com/website/58-transphobia-and-the-right-stuff

In the Name of the Fa

There will be a new episode of IDSG along later today. In the meantime, here is a substantially re-edited and rewritten/updated section of something I wrote and originally published for supporters only at my Patreon. As it happens, the subjects discussed below have a fair bit of relevance to the main topic to today's forthcoming new IDSG.

*

On 31st May 2020, President Donald Trump tweeted:

“The United States of America will be designating ANTIFA as a Terrorist Organisation.”

The statement is meaningless in real terms. As has been widely remarked, ‘ANTIFA’ (even Trump’s use of all-caps is telling of where he’s getting his ‘information’) is not an organisation at all. It is not a group of people who do things; it is a way of doing a certain thing, namely: opposing fascism. To be specific: it is a strategy of direct action for confronting fascists, fascism, or things deemed liable to incite or encourage the growth of fascism. It is a diffuse, rhizomatic, leaderless cloud of people; connected not by membership or hierarchy but by shared goals and tactics - and even that very broadly. Nor, as has also been widely remarked, does Trump - or indeed ‘The United States of America’ (whatever he might mean by that) - have the ability to ‘designate’ (whatever he might mean by that) anybody or anything ‘a Terrorist Organisation’. (...though Attorney General William Barr subsequently indicated that Trump’s threat - which he has made before - might be implemented in some form. Since this was originally written, mysterious hybrids of ICE and the DHS have started their Orwellian black-bagging of protestors. The lack of clarity and formal legal powers was never going to be a problem. Indeed, the mutation of nebulous reaction and state gangsterism into intensely codified and punctilious legality, with liberals and centrists always taken by surprise, is a fascistic hallmark.)

The tweet is pure Trump in that it reeks of truculent political illiteracy, barely concealed sadism, paranoid terror, adolescent performative swagger, and a kind of egomania that can fairly be called Hitlerian since Hitler also messianically equated himself and his emotions with his entire nation. What is remarkable, as ever, is how little it matters. Because, as detached from reality as Trump’s statement may be, it nonetheless serves a very real, tangible political function and gives every appearance of being well crafted to be effective and dangerous. And it manages this, as so often with Trump’s addresses, by being aimed far above the heads of the establishment and the professional pundits. It not being aimed at them, their rebuttals also fail to connect with anything or anyone. It is also characteristic of Trump that he manages to be an incredibly skilled politician via the unexpectedly effective tactic of being an irrational ignoramus. Gibberish though it is, the tweet sends a very definite political message out into the ether where anybody and everybody can hear it and react to it as they choose - and of course Trump knows the kinds of people who will choose to react to it in a certain way, even if they only absorb it with, and as nothing more than, a shrug. One of the characteristics of Trumpism as a fascistic event is the circular mutual radicalisation of Trump's base and the fascistic trend in government.

The ultimate Facebook grandpa, Trump has stumbled bassackwards (via the simple expedient of being staggeringly rich and even more staggeringly stupid, and making a bid for attention and his own show on Fox at the historical moment when the ‘long depression’ was so undermining capitalism and the legitimacy and efficiency of neoliberal government that ‘creeping fascism’ began to appear) into the ultimate Facebook grampa dream: he can spend all day watching Fox News, tweet angrily about the stuff he saw that made him angry, and huge numbers of people will a) listen, b) click Like, and c) sometimes go out and Do Something about it. The Something that they do takes many forms, one of them being the ‘stochastic terrorism’ of the resurgent far-right (though I don’t suggest that all of them are Trump loyalists, or that Trump’s twitter witterings are all that motivates them - far from it.) Indeed, these days the actual fascists of the former ‘alt-right’ are generally disillusioned with Trump, he having failed to deliver the Day of the Rope (as they lovingly call the day after they win the race war and proceed to murder all the remaining black people, gay people, left-wingers, etc) a couple of weeks after his inauguration.

The point is that Trump knows full well what he is doing when he tweets things like this, or like “when the looting starts, the shooting starts”. He is signalling to the troops on the ground - be they cops or national guard or less official groups - in the middle of the protests that they can attack, shoot, beat, maim, arrest, and kill with impunity, as long as the people they do it to are the Enemy. This may not actually be true - I daresay a few officers will find that they do not actually have presidentially-approved blanket impunity from any consequences at all - but it’ll be too late by then. And the rebellion will have been crushed. That’s the plan, anyway. And Trump will enjoy immunity, of course. He will be criticised. He will be repeatedly owned on Twitter by clever liberals. He will be repeatedly excoriated in clever articles. But he will, at the end, suffer no consequences. He never has so far! Indeed, the consequences for him have always been liberating and exciting, in that the radicalisation he engenders comes back to him in the form of permission.

Trump may or may not technically be a fascist depending on your definition (personally I would distinguish between ‘fascism’ and ‘the fascistic’) but he is certainly hoping to make this rebellion (initially against the police murder of George Floyd) - and everything else it stands for, from the catalogue of police killings of African Americans through to the fact that coronavirus is only the latest curse that hits Black America ten times harder than it hits White America - into his Reichstag Fire moment. He does not of course know anything about the Reichstag Fire (he reportedly kept a book of Hitler’s speeches next to his bed but almost certainly didn’t get through it) but he knows instinctively that he needs one.

And here we start to hear the siren song of the liberal centrist who warns that by opposing fascism with ‘violence’ and ‘left authoritarianism’ and ‘attacks on free speech for all’, the antifascist actually helps the fascists! “When you think you’re punching nazis you don’t realise you’re also punching your cause,” we’re informed by Trevor Noah, who described Antifa as “vegan ISIS” (which, like so much of the bilge we get from Noah and those like him, is joke shaped but lacks the internal connections to actually qualify as a joke). He speaks for many. (Though, of course, when we say of Noah and people like him that “he speaks” we actually mean his team of writers.) Far better than barracking them and ‘attacking’ them in the street, far better than shutting them down when they march or organise, far better than protesting when they or their favourite intellectuals are invited to speak on campuses or high-listenership podcasts, we should rather let fascists speak and engage them in reasoned debate, sunlight being the best disinfectant and all that. It might be easy to be seduced by this if one lacked any understanding of what fascism is, or any knowledge of its history. Sadly, lack of understanding of politics or knowledge of history are quintessential traits - one might even say mandatory qualifications - of the species known as the mainstream pundit or opinioneer. Bill Maher claimed victory after inviting Milo Yiannopolous on his show and flattering him in front of millions of viewers, whereas it was actually activists unearthing not-terribly well-hidden dirt on Milo that ended his ascent to respectability in polite reactionary society, and the slow and grinding work of years by antifascists - protesting, haranguing, barracking him everywhere he went - that eventually wore him down to the point where he now scrapes a living working for Alex Jones.

It's worth being very clear about the stakes here: damaged by the catastrophic way he has 'handled' the Covid-19 pandemic, Trump is almost certainly going to attempt to run his campaign for reelection based on scaremongering about, and authoritarian response to, Antifa and Black Lives Matter, which he will confect into hallucinogenic threats to the freedom and security of the nation. The fundamental basis of this strategy is, of course, the widespread authoritarianism and racism (always mixed with other forms of bigotry) that prevail in many sectors of US society, especially among those who constitute Trump's base of existing or potential support. We're talking about nothing less than the mestastacizing of Trumpism into an actual fascist government project (as opposed to a fascistic one... which is bad enough), based on the acceleration of Trumpism's inherent fascistic strain in response to an outbreak of revolt from below. We're already literally seeing it happen on the streets. Nobody should deny that there are heavy lines of continuity between Trumpism and 'normal' American politics, that it emerges from and grows within a deeply racist and authoritarian 'mainstream'. But fascism always does. The point to emphaszie at this moment of intense danger is the rupture. Trump is also poised to deny the result of the 2020 US general election if it goes against him. We are looking directly at the imminent arrival of the worst case scenario.

It's also worth being very clear about the fact that the irruption of struggle from below is what is catalysing this acceleration. But this is not to reprove the struggle from below. On the contrary. It is, or should be, a call to intensify it and align behind it, so that it can continue. Because it is not only good in itself, despite its blowback from the system, it is also the only force that can stop the 'creeping fascism' of which Trumpism is the political spearhead within the tottering and mutating neoliberal capitalist state. It is now too late to stop and turn back. Doing so would not stop the growth of the reaction, any more than the defeats of the waves of strikes and occupations in Italy stopped the arrival of Mussolini, or the defeat of the German revolution stopped the coming of Hitler. On the contrary, these defeats emboldened fascism and Nazism in their bid to reconstitute the capitalist national state to be proof against the internal contradictions which put it in danger from crisis and revolt.

If the protests accelerate, any movements, organisations, slogans, etc, invented and used by the protestors will be seized upon by the reaction, demonized and used to spready the paranoia and authoritarian yearning that legitimises the fascist response. As I say, Trump and Trumpism are already doing this with Antifa and BLM, and will continue to do so. But they will do the same thing, emboldened, probably more strongly, if the protests ebb. And they will be helped at every state by the respectable, sensible, mainstream lefties and liberals and centrists. Because such people find movements from below as threatening as Trump does - precisely because, despite being movements against racial injustice, these are manifestly working class movements from below. The fact that the fascistic strain within the ruling class and those aligned with it will ruthlessly shut down the liberal/centrist strain if given a chance does not mean that the liberal/centrist strain will turn away from a class alliance with fascism, right up to the point of its own destruction. They will see Antifa, BLM, and even the Sandersnistas, as a greater threat, right up until fascism comes up behind them and shoots them in the head. This does not, of course, mean that alliances shouldn't be sought and forged where they can be. On the contrary. The politics that rejects such alliances is equally suicidal and, for all the supposed purity of revolutionary class politics supposedly motivating it, actually derives from a fetishisation of electoralism and reformism. Alliances must be made across the left. But a lot of the people who ought to be ready to join in an anti-fascist united front - at least going by what they say - are not, because they see the cure as worse than the disease, or equivalent.

The real problem with Antifa as far as respectable, sensible, mainstream lefties and liberals and centrists are concerned is not that they oppose fascism in the wrong way, but that they actively oppose it at all. I don’t mean that such people are secretly pro-fascist. They’re not, though they are objectively pro lots of things that are far from inimical to fascism, being supporters of a system with more in common with fascism than it has against it. No, I mean that they are anti-fascist but only because it is a threat to them and the system they represent and benefit from. In the 30s, Orwell warned the left that “you have got to drive away the mealy-mouthed Liberal who wants foreign Fascism destroyed in order that he may go on drawing his dividends peacefully – the type of humbug who passes resolutions “against Fascism and Communism”, i.e. against rats and rat-poison.” Depressingly little has changed.

The values such people claim to hold dear are expressions of their class position and interests, hence the ease with which they compromise or jettison them routinely when that same system (and their class interests) require it. Moreover, they oppose Antifa for pretty much exactly the same reason they oppose fascism: it represents politics being grabbed by grubby hands, usurped from the hegemony of its proper stewards in the professional political and media classes, i.e. them. This is why, to them, fascism and socialism look like cousin varieties of the same problem, namely: the wrong people, out and about, making nuisances of themselves, interfering in matters that are outside their proper province.

There was much talk after Trump’s election of a revenge by the ‘left behind of neoliberalism’. This proved to be false. In actual fact, Trump’s base is not to be found among the ravaged working classes or unemployed, the ‘left behind’ of neoliberalism, but among the US’s extensive, relatively prosperous, but squeezed middle layer. The average Trump voter is white and college-educated, fairly well-off but subject to all sorts of pressures. Trumpism fails to map directly onto classical fascism in all sorts of ways, but in this it corresponds quite closely, albeit with inevitable distinctions. Trumpism is powered, to an extent, by ‘economic anxiety’, but it is not, by and large, the ‘economic anxiety’ of the worker or the poor, but rather of the petty bourgeoisie who survived ‘08 scathed and never fully crawled out from under it, the prosperous white collar guy who sees his mortgage and insurance and energy bills getting steeper and his savings worth less, and the great layer of functionaries who serve the state in the capacity of enforcers, i.e. the police. Trumpism, like classical fascism (albeit with inevitable differences that some try to use as gotchas to disprove the validity of any comparisons to fascism), is based in the “human dust” of the middle classes, as Trotsky called them. Neither of the working class nor of the ruling class, separated from the great mass of workers by relative prosperity and prestige but far below the ever-more-distant pinnacle of wealth, and frequently fucked-over by establishment politicians, even as their vote is endlessly courted with rhetoric about values. Despite all the claims to break with the discredited politics of the past, Trumpism just pulled over another version of the old ‘values’ trick, disguising itself by going brazenly for the kind of openly racist talk that the establishment abandoned (at least in public) decades ago. All those guys with ‘Blue Lives Matter’ stickers and Punisher decals on their cars were captivated by Trump’s Mexican rapists, the Caravan, and the “not people… animals” of MS-13, just as others before them have been captivated by welfare queens and superpredators and godless teachers preaching the heresy of evolution and contraception.

But here again, we need to be very clear: the animating principle of Trumpism and its social base, and thus of the nascent mass movement sector of American fascism, is authoritarian racism. in this it is a symptom of the fact that US capitalism is based upon the racism which animated settler-colonialism, slavery and imperialism, and which thus organises US capitalism as a deep logic. And, at the moment, the animating principle of the protest movements is anti-racism or, to be more precise, a widespread rejection of that deep logic and the status quo it props up by the victims. The right-wing attempts to paint the entire movement as an emanation of Antifa, with Antifa as mainly white middle-class college kids, is a direct attempt to delegitimate the movement not only in itself but as a bottom-up movement for racial social justice by those oppressed by systemic and state racism. The "anti-antifa is just fa" joke actually gets at a very important point: for a lot of people, especially those in those middle layers who fetishize the 'normal' (the 'normal' being, of course, the baseline authoritarian racism and racial injustice of US capitalism), their fascist politics will be constituted of being anti-antifa, and thus will they arrive back at fa. Just as 'All Lives Matter' is not a racist statement because of its context, so opposition to Antifa (opposition that is, not criticism) is now, in meaning and effect, fascism. And every time the media, or the sensible liberal centrists who are so concerned about free speech, demonize protest by painting it as dangerous authoritarianism, they are thus greasing the slide of the democracy they claim to love down into the pit.

Because all this is happening in the context of a larger-scale process that has been called ‘creeping fascism’. Contrary to myth, neoliberal capitalism has never been about ‘rolling back the frontiers of the state’ in areas other than welfare spending or infrastructure investment. It has always been punitive, carceral and imperialistic. You need the militarised police and the prisons (often privatised) to cope with the social problems that explode once you withdraw social spending. Neoliberalism has always been evolving more and more authoritarian methods of government, including sinister methods of monitoring the movements - physical and virtual - of individuals. But recently, neoliberal ‘democracies’ have been embracing fascistic forms of politics and leadership. For all the continuity that exists between the new form and the old (and Trump is far more like Obama and Clinton than he is different) this is definitely a rupture, not only quantitative but qualitative. Trump is not only worse than what has gone before; he is essentially different. He may or may not be ‘a fascist’ (there comes a point where such technical definitions become shackles rather than tools) but he and the politics he represents are, almost without doubt, ‘fascistic’. Categories are excellent servants and terrible masters. This is a qualitative change that may be partly a result of the slow quantitative build-up of state authoritarianism, and is definitely related to the cultural changes that neoliberalism has wrought on societies where it reigns, whether deliberately in its capacity as a deliberate counter-revolution or blindly via the way it has eroded social bonds and the economic security of millions. At a deep level, the current creeping fascism and the neoliberalism which gave birth to it are both political symptoms of the longstanding economic stagnation and decline of capitalism's ability to sustain profit levels, a 'stagcline' that has accelerated since 2008's crash.

At the same time, the corporate media is more hegemonic (concentrated and centralised) than ever and is spawning more and more demagogic right-wingers with recognisably fascistic rhetoric who are suffered to dwell within the ‘mainstream’, albeit mostly at the edges. This has been happening for a while now, but seems to flowering now, especially in the person of Tucker Carlson (whose head writer Blake Neff was recently found to frequent racist online forums and spout open racism). Carlson is admired by far-right types for a good reason; much of what he says is straightforwardly fascistic - in both content and style - to anyone who knows the ideological markers and ticks of fascism. Fox News may be the rightmost edge of the ‘mainstream’ but it is mainstream, despite its attempts to position itself as a brave outlier up against a left-wing media establishment. Carlson’s quantum leap from standard right-Republicanism to outright fascistic rhetoric is probably a spearhead rather than an endpoint. This sort of ideological drift always has an open field on the right. Fox tends to be pulled rightward by its most successful rightmost voices. Fox has had a rightward-pulling effect on the rest of the US ‘mainstream’ media. And Fox, in the person of Carlson, is trying to outbid a burgeoning right-wing media ecosystem which now includes a groundswell of fascist and fascistic media coming from below via free platforms like YouTube, which is a cesspool of fascistic opinions. So we’re seeing the ideological production system of today’s crisis-ridden neoliberalism being pushed in a fascistic direction by the rising propaganda of an embryonic fascistic mass-movement.

This is not the place to go into this in detail, but it is worth noting that the coronavirus pandemic is likely to speed up the process. Not only have many governments already introduced authoritarian measures for dealing with it (with even the arguably necessary ones worrying in the irresponsible hands of our current rulers), but it has sparked arguably the most catastrophic economic crash in the history of capitalism. The Great Recession of 2008 began an era of slump which Marxist economist Michael Roberts has dubbed the ‘Long Depression’. ‘Creeping fascism’ must be seen in the context of this ‘long depression’. The economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic is orders of magnitude worse than the crash of ‘08 and, in the absence of radical government policies which seem unlikely to materialise, is likely to lead to an even worse and more sustained ‘long depression’. All the political crises ultimately spawned by the ‘long depression’ since ‘08 - crises of legitimacy and deadlock for democratic governments, ‘creeping fascism’, the rise of the radical right, the carnival of reaction that is Brexit, the ascendancy of Trump, the rise of other such fascistic (as distinct from just authoritarian or right-wing) leaders like Modi and Bolsonaro, the ‘post-truth’ phenomenon - are likely to continue, and to be intensified globally, by the post-corona slump into which we’re headed. In tandem with the onrushing climate catastrophe, the corona slump is only likely to accelerate both the rise of fascist movements and the authoritarian, quasi-fascistic drift of the mainstream and the establishment.

Just as everyone is in favour of ‘legitimate protest’ (though definitions are thin on the ground and, in practice, very little protest seems to actually be legitimate), so nobody is pro-fascism. At least, nobody admits to it (often not even the fascists). People like sharing that fake Churchill quote about how “the fascists of tomorrow will declare themselves anti-fascists”, seemingly not noticing that it cuts both ways. Whoever actually did say that was kind of right, in that so many of today’s fascists would declare themselves non-fascists and anti-fascists, absolutely opposed to fascism, frequently slandered with comparisons to fascists by the left who - in their desire to silence those who bravely speak the un-PC untruths the world needs to hear - are themselves the real fascists. In fascists, this sort of reasoning is often simply conscious dishonesty, or a kind of self-justified triangulation in the name of higher truths and aims. But the basic thinking isn’t confined to fascists… which is why they use it: it resonates. And, as with racism considered by so many white people, the thinking seems to run thus: Fascism is bad; I’m a good person; ergo I can’t be a fascist. Job done. The fascism that ‘everyone’ is against is the notional, nebulous, contentless, ahistorical, depoliticised, aesthetic fascism which is just mean people who want to tell you what to do. It’s the fascism of Darth Vader and Voldemort. Rowling has, of course, denounced the fascism of both left and right.

In practice, the ‘tolerance’ of the centre turns out to look like this, time and again. This kind of thinking is terrifyingly widespread, not least precisely because it is relentlessly promoted by the capitalist culture industries. We have reached a point where so many people are so politically uneducated and disoriented, as a result of decades of neoliberal cultural counter-revolution (against the high-points of political knowledge, theorising and struggle in the West in the 1960s), that we find people tweeting things about how nice it would be if we could all - communists, fascists, Jews - just agree to tolerate each other and march together with our banners - hammer and sickle, swastika, Star of David - side by side, and all respect each others points of view and right to speak. This looks like tolerance - at least if you don’t actually look at it or think about it. It’s actually a betrayal of the people the fascists want to destroy, a de facto refusal to tolerate them because they commit the unpardonable sin of causing strife through their lack of enthusiasm for being killed. It is also, in practice, an invitation to fascism to rise and keep rising. This is, objectively, a kind of alliance with fascism. History shows us that it is an alliance which happens again and again where fascism rises. It doesn’t get less serious or less enabling. It gets more so. It has been a vital part of fascism’s ascendancy, where it did ascend. This is where equating fascism with all dissent gets you. This is where equating tolerance with goodness gets you.

This is why the mainstream has such an issue with Antifa and active, ‘violent’ antifascism generally. It is not that the people who are prepared to cheerlead for, or tolerate, or try to gradually phase out the manifold horrors of capitalism - poverty, inequality, imperialist war, environmental devastation - are so moral that the sight of violence offends their moist eyes and pristine consciences. The problem is that they are seeing the legitimacy of the monopoly on violence - and more broadly on activity, on power - by the establishment, the capitalist state, challenged from below by ordinary people. That the people in question tend to come from somewhere on the radical left - from revolutionary socialists and communists and wobblies to anarchists and syndicalists - is both to be expected (because the left generally understand fascism and the threat it poses better) and also a further reason for the mainstream to hate and fear them when they see them. Of course, to such people, it looks like “fascism of the left or right” because, to them, their perception buttressed and promulgated by a hundred movies and books and newspaper articles, fascism reduces down to a contextless and depoliticised and ahistorical sort of organised ‘intolerance’; it is the enemy of liberalism and liberalism is the only hope for democracy and fairness; and it rises from below as a sort of excrescence of the ill-educated, its fundamental cause to be found in unchallenged irrationality. Of course it seems to these people like the proper way to deal with it is to endlessly debate it - platforming it all the while - so that it can be disproved and discredited. That way, it goes away because, far from being an emanation of the capitalist system in crisis and deadlock, it is a sort of atavism of the idiotic, people who just need liberal democracy to set them straight. When they see the left, organised and armed, out there fighting the fascists, they see another problem, something in the way of the debate, a barrier between them and both the ideological triumph of liberalism and the monopolistic legitimacy of the liberal state. They see a mass of the great unwashed, brawling, shouting equally threatening slogans at each other. They see politics drained of all content. They see pure form. Ugly form. And they want it cleaned up. And, of course, when they issue the inevitable conclusions from these thought processes for the umpteenth time, and get slapped down by antifascists who’ve heard it all before and know it amounts to fiddling while Rome burns, endlessly reciting that Martin Niemoller poem (with the sympathetic reference to communists decorously censored) while the nazis take your neighbour away, they’re infuriated at being told that they’re not helping, and they interpret the criticism from one tribe of people in black as authoritarianism, a threat to their free speech - this being, of course, the ultimate concern of the middle class writer or intellectual, after they’ve consumed endless reassurances that the main problem with political tyranny is how it impacts on the editorial freedom of middle class writers and intellectuals.

The problem is that this highly convenient morass of ideological confusion not only allows for but promotes the same agenda Trump is now consciously cultivating as a winning strategy. And, more deeply, it both reflects and enables the deep process of which trump is but the symptom, abeit perhaps a decisive one, the process whereby capitalism is attempting to salvage itself by mutating from neoliberalism into a kindred new form of fascism.

Gramsci said that fascism triumphed in Italy because the socialists disdained the spontaneous movements. So my message to socialists would be: don't disdain the spontaneous movements. Align behind them. No spuriously pure class politics must hinder this. This is the class flexing its latent power.

July 20, 2020

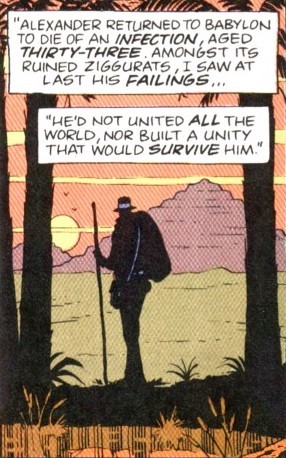

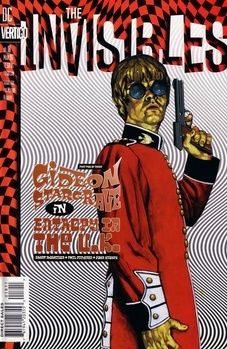

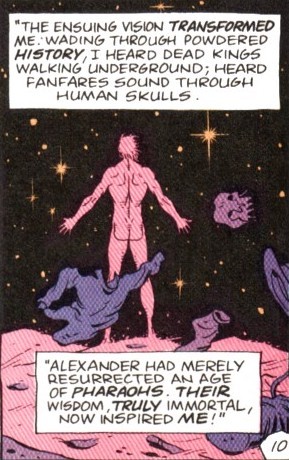

The Last War in Albion Book Two, Chapter Eleven: By Another Mans (Look Upon My Works Ye Mighty)

Quick update on Christine's Patreon. There's been a tremendous response, but she's stalled at around $208 at the time I'm writing this on Saturday. Financial security for her really needs about $300, so if you're at all interested in her amazing Kate Bush work, please check it out. Also, she's got fun intermediate goals: at $225 she'll be doing a podcast with Daniel Harper, and at $250 another with Jack Graham about Alien and The Shining. So please, help my daughter afford an apartment via her Patreon.

Quick update on Christine's Patreon. There's been a tremendous response, but she's stalled at around $208 at the time I'm writing this on Saturday. Financial security for her really needs about $300, so if you're at all interested in her amazing Kate Bush work, please check it out. Also, she's got fun intermediate goals: at $225 she'll be doing a podcast with Daniel Harper, and at $250 another with Jack Graham about Alien and The Shining. So please, help my daughter afford an apartment via her Patreon.

And so at last the story returns to where it began. Grant Morrison has, of course, been ever-present. As already discussed at length, his first professional credit predated Moore by five months. But he has been a shadow presence in the narrative, lurking at the edges, occasionally contriving to intersect it, waiting for his moment to take the stage in earnest. And now at last he arrives having always been here, and it becomes necessary to trace the story backwards, figuring out who he has been all this time.

This is, of course, a strange moment in which to observe Morrison, as he remains resolutely unspectacular. The work through which he will define himself is still ahead, the earliest plausible instances of it not emerging until two months after Watchmen finishes, his American debut still almost a full year away. At this point his greatest accomplishment is Zoids, where he surely acquitted himself well, but where he no more established himself as an impending major talent than Alan Moore established himself as the man about to revolutionize comics with Skizz or Captain Britain. His career at this point has no V for Vendetta or Marvelman, nor even a Ballad of Halo Jones. To read the future out of this moment is to work in implication, finding patterns in the negative space. Getting it right is more about knowing the answer ahead of time than insight.

As a result, it is easy to overreach—to confuse historical event and inevitability. On a very basic level, whatever larger conclusions and patterns are inferred, the answer to how Grant Morrison achieved what he did and how he took up his role in the War is simple: he put a lot of work into writing comics that changed the world. This work did not exist in a vacuum; plenty of extremely talented people have worked just has hard to have an insignificant fraction of the insight. Nevertheless, to treat Morrison’s career as some historically deterministic phenomenon that extended out of Alan Moore’s actions would be an egregious error.

As a result, it is easy to overreach—to confuse historical event and inevitability. On a very basic level, whatever larger conclusions and patterns are inferred, the answer to how Grant Morrison achieved what he did and how he took up his role in the War is simple: he put a lot of work into writing comics that changed the world. This work did not exist in a vacuum; plenty of extremely talented people have worked just has hard to have an insignificant fraction of the insight. Nevertheless, to treat Morrison’s career as some historically deterministic phenomenon that extended out of Alan Moore’s actions would be an egregious error.

So too would it be to suggest, as Morrison repeatedly does, that his career could have happened without Moore. Did Morrison come to writing comics on his own? Yes. Did he have his own interests and influences that, while certainly overlapping with Moore, were nevertheless his, interpreted and responded in ways utterly and necessarily unique to him? Yes. But none of that changes the fact that the career Grant Morrison had existed in a large part because Alan Moore did it first. The wave of Karen Berger edited books that started with Animal Man happened because Alan Moore did Swamp Thing. The genre of literate, politically invested superhero comics for adults that Morrison made his name in originated with Marvelman and V for Vendetta. Morrison admits as much, both in 1985 when he acknowledges that “only the advent of Warrior convinced me that writing comics was a worthwhile occupation for a young man” and much later in Supergods when he describes how he and the rest of his generation hit the American superhero scene in the wake of Moore: “And so we arrived in our teens and twenties, in our leather jackets and Chelsea boots, with our crepesoled brothel creepers and skinhead Ben Shermans, metal tattoos, and infected piercings. We brought to bear on the ongoing American superhero discourse the invigorating influence of alternative lifestyles, punk rock, fringe theater, and tight black jeans. We rolled up in anarchist hordes, in rowdy busloads, drinking the bars dry, munching our hosts’ buttocks (artist Glenn Fabry drunkenly assaulted editor Karen Berger’s glutes with his molars), and swearing in a dozen or more baffling regional accents. The Americans expected us to be brilliant punks and, eager to please our masters, we sensitive, artistic boys did our best to live up to our hype.”

The truth is that it was never Moore’s work that Morrison was imitating, but his career. There are similarities in their works, yes, but the truth is that there are even more similarities between Moore’s work and that of Neil Gaiman, whose early DC comics are much more faithful in their imitations of Swamp Thing than Morrison’s. So why is Gaiman the acknowledged protege and Morrison the despised rival? Again, one answer to this question extends out of specific decisions and choices—specific actions Morrison took in crafting his public persona that alienated Moore, and specific decisions both men made in the face of that antipathy. Another answer, however, is more esoteric, extending less out of decisions anybody made than out of the fundamental cultural relationships in play—a necessary consequence of the particular streams of influence and iconography that both men brought to the precise historical moment they did.

Figure 1140: Grant Morrison's illustration for his article on sword and sorcery comics. (From White Tree #2, 1977)

In this regard, contributing factors. First of all, Morrison was always more straightforwardly rooted in superheroes and genre fiction than Moore. He writes of this love with vivid and tangible passion throughout Supergods, making it clear that superheroes were not merely a genre he enjoyed, but something deep and central to who he was in a way that none of Moore’s comments on childhood love of the genre ever suggested. For Morrison, superheroes were an object of almost religious importance, the “Faster, Stronger, Better Idea” that could fight “the Idea of the Bomb that ravaged my dreams.” As he puts it bluntly in Talking With Gods, during a period in which he didn’t go out or do anything, “I really felt like they’d saved my life in a way.” Even his wider interests tended to circle back to this—a 1977 article for the fantasy fanzine White Tree, to which Morrison also contributed the an ongoing serial entitled Armageddon and Red Wine, tackled the genre of sword and sorcery literature through the lens of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian comics. And indeed, the fact that his 1970s zine work was on fantasy in the general case, in contrast with, say, Alan Moore, who was bouncing around the Northampton Arts Lab dabbling in a broader spectrum of avant garde and performance art.

Even when Morrison, in his account, fell out of love with superhero comics for a couple of years following his disappointment at the 1978 Superman vs. Muhammad Ali (a period, notably, that overlapped precisely with Captain Clyde), his interests stayed broadly in the sci-fi/fantasy niche. Where Moore had roots in the avant garde and the underground comix scene as well, Morrison had more of a singular tap root into the sci-fi/fantasy genre in general, and superheroes in particular. This is not to suggest that Morrison’s roots were comparatively impoverished, although Moore would surely draw that conclusion, nor that Moore’s roots did not also contain deep affection for and knowledge of superheroes. Simply that at the end of the day, Morrison had a loyalty to the specific genre of superhero comics that Moore did not.

A second factor: Morrison was, from the start of his career, also overtly working with magic. This commenced somewhere around the beginning of 1979 when Morrison’s uncle gave him Frieda Harris and Aleister Crowley’s Tarot deck along with a copy of Crowley’s The Book of Thoth. Intrigued, he sent away for The Lamp of Thoth, a British occult magazine of the 80s. He was quickly drawn to the then emerging chaos magic scene, which had largely been kickstarted by the publication of Peter Carroll’s Liber Null the year before. Describing his first ritual, he recounts performing an “invitation to magic,” asking it to let him in. “I got the candles out, I did the magic words, I did the circle, I did the banishing and all that stuff,” he explains. Laying down after, “there was a kind of gravitational point in the air int he room which was drawing all the perspectives towards it as if there was a hole there or a crack. And there was the sense of black oil filling up the folds between the brain.” Scared, he appealed to Jesus, at which point an angelic lion’s head manifested, proclaiming “I am neither north nor south.”

Figure 1141: Grant Morrison's familiarity with magic was evident as early as Gideon Stargrave. (Written and drawn by Grant Morrison, from "The Vatican Conspiracy" in Near Myths #4, 1979)

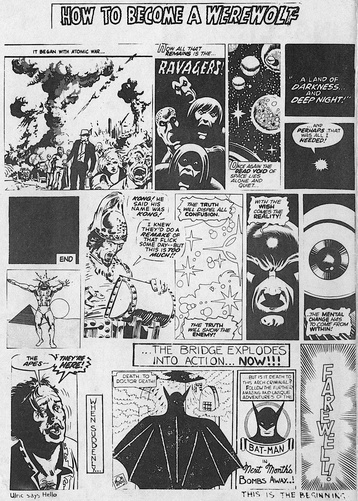

Lest one believe that this is post facto justification contrived as part of his rivalry with Alan Moore—an accusation Moore leveled in his incendiary “last” interview, where he claims that “several months after I’d announced my own entry into occultism and the visionary episode which I believed Steve Moore and myself to have experienced in January, 1994, Grant Morrison apparently had his own mystical vision and decided that he too would become a magician”—Morrison’s early career work entirely supports his account of things. The Vatican Conspiracy contains a panel in which someone conducts a ritual to consecrate a circle taken from Reginald Scot’s 1584 The Discoverie of Witchcraft, conducted in what is recognizably a Circle of Solomon as described in The Lesser Key of Solomomn. And his 1983 zine Bombs Away Batman contains a page of book recommendations including the Illuminatus! Trilogy, Michael Talbot’s Mysticism and the New Physics, and Aleister Crowley’s Magick. (“Learn to manipulate reality with Old Uncle Aleister. If you’re sceptical it’s your duty to try it out for yourself.”) It’s not even possible to argue that Moore was instrumental in Morrison’s decision to be open about his occult interests: he talks about it in multiple interviews going as far back as 1988, where he talked to Arkensword about his “forays into the occult, specifically into Chaos Magick, the current that's revolutionised the occult world during the last 6 or 7 years.”