Philip Sandifer's Blog, page 5

September 14, 2020

Suspended in Gaffa

Suspended in Gaffa

2018 Remaster

Houba Houba (France, ‘82)

Bananas (West Germany, ’82)

Music video

Hey, all. Sorry to shill for myself once again, but the Patreon has been slipping a little. $300 is the bare minimum where I can comfortably live  off my blogging, and the Patreon has dipped below that slightly. Any help is appreciated.

off my blogging, and the Patreon has dipped below that slightly. Any help is appreciated.

After a few weeks working with Bush in Townhouse Studios, a mollified Hugh Padgham was called to musical duties elsewhere. Bush commissioned the younger Nick Launay, who was coming off production duties on Public Image Ltd.’s drums-and-reverb LP Flowers of Romance, to replace Padgham. The close ages of the two collaborators (Bush was 22, Launay was 20) assisted their rush into youthful creative maximalism. “[It] really was like the kids are in control,” effused Launay. “I came from the punk rock thing, and to me she was punk rock.” Bush and Launay’s work together produced an attitude of kitchen sink realism, if you define kitchen sink realism as “we’ll throw the kitchen sink off a cliff and it’ll sound real neat!”

Bush’s newfound role as producer is at the heart of The Dreaming. For all intents and purposes, she was now completely in charge of her work and exerted her agency by trying out every idea she had. Collaborators were often stymied by her ideas (Aramaic instructions written in disappearing ink do not tend to endear a producer to their session musicians) — Brian Bath was particularly flummoxed, and Del Palmer has admitted in the years since The Dreaming’s release that Bush has since become “a bit more discerning.” To stake out her own territory meant Bush had to embrace uncertainty, resulting in the most restive and strangest record of her life.

Public response was ambiguous. In the years since its release, The Dreaming has gained a reputation as Bush’s most underrated album. This is a slight exaggeration, if a basically understandable one. The Dreaming peaked at #3 in the UK, but it domestically sold a relative paucity of 60,000 units (to compare, Never for Ever sold 100,000 UK units, and even Lionheart hit 300,000). It wasn’t close to a commercial failure by any means, but it was decidedly less popular than Bush’s prior work. This can be explained by a number of factors, from the obvious aesthetic ones (The Dreaming’s maximalism was viewed by some as a bridge too far for Bush), to timing (“Sat In Your Lap” predated the album’s release by over a year), and EMI’s timid promotional campaign. Reviews were mixed, if better than they’re sometimes declared in retrospect. The indelibly truculent Robert Christgau offered The Dreaming a conditionally approbatory review (“the most impressive Fripp/Gabriel-style art-rock album of the postpunk [sic] refulgence makes lines like ‘I love life’ and ‘some say knowledge is something that you never have’ say something”). Melody Maker’s Colin Irwin effused about Bush’s “fearsome twisted voice” for “put[ting] the fear of God in me,” while future Pet Shop Boy Neil Tennant observed Bush’s efforts to “become less commercial.” Record Mirror’s Daniella Soave curtly acknowledged Bush’s ambitions while saying “until I’ve heard it another 50 times I haven’t a clue.” What stands out in the majority of reviews is their areas of accord: everyone agreed that The Dreaming was defined by multiplicity, weirdness, a distinct non-commercialism, and a willingness to try everything. Even if listeners couldn’t agree on whether The Dreaming worked, everyone had a grasp on what it was.

This degree of unified disagreement speaks volumes on the nature of The Dreaming. For a pointedly (and willfully) unkempt LP, its nucleus of formal ambition and complex emotional catharsis is remarkably consistent. The album boils down to an exploration of fairly close-knit concepts: the liberatory effects of madness in women, the untethering of the subconscious, the symbiosis of body and mind, and the aching voice of repressed people. Its ethos is a cathartic one, about freeing one’s emotions from self-imposed bondage. The resulting emotions can be scary, but The Dreaming treats that as neither positive nor negative, merely a fact of having emotions.

One perspective that appears throughout The Dreaming is that of childhood and play — it treats the untethering of the subconscious as revealing a small, confused child. From one perspective of maturity, people can be viewed as complex adult emotions and cynicism burying a repressed inner child. “Suspended in Gaffa” certainly lends itself to this reading. Panto-like in its musical qualities (and certainly in its music video, which we’ll get back to shortly), it’s a waltz in C major, playful and initially parsimonious. Par for the course in The Dreaming, the verse’s chord progressions follow the rhythm in shape, particularly with its descending patterns of two major chords followed by minor chords (V-IV-ii, then V-IV-vi-iii), with a result of nearly staccato chipperness and a less cheerful supertonic or submediant. Its buoyancy is something of a ploy though — Bush’s vocal, while acrobatic in its emphatic lunges towards certain syllables (“OUT/in the GARden/there’s HALF of a HEAVen”), maintains a certain reservation often running lyrics together (“Whenever I’ve sung this song I’ve hoped that my breath would hold out for the first few phrases, as there is no gap to breathe in,” Bush wrote later), as Bush sings primarily from the back of her throat with results that sound like she’s gulping the lyrics, likely a frustrating move to listeners with less patience for Bush’s sometimes unintelligible lyrics. “FEET Of MUD” and “IT ALL GOES SLO-MO” are certainly B.V.s for the ages.

Yet at the core of this excess, there’s a simplicity to “Suspended in Gaffa.” It has the same expansive and consumptive obsessions as its sister songs — youthful aporia, an obsession with an unreachable god, a desire to unite with the subconscious. Yet it filters this through a childlike, somewhat Carrollian filter, with a surfeit of internal rhymes, abstract nouns, and ambiguous pronouns like “out in the garden/there’s half of a heaven/and we’re only bluffing,” “I try to get nearer/but as it gets clearer/there’s something appears in the way,” “I pull out the plank and say/thankee for yanking me back/to the fact that there’s always something to distract.”

The lyric is an endless series of prevarications, often relating to knowledge, or the unattainability of it (see “Sat in Your Lap”). The refrain’s “not till I’m ready for you,” “can I have it all now?/we can’t have it all,” “but they’ve told us/unless we can prove that we’re doing it/we can’t have it all” speak to an “all or nothing” approach, not identifying exactly what’s at stake so much as its urgency. Desire gets codified as an end in itself, often for a god (“I caught a glimpse of a god/all shining and bright”) — “until I’m ready for you” gives away the game (constructive spiritual union with a deity is impossible if one is unready to consent). “The idea of the song is that of being given a glimpse of ‘God’ — something that we dearly want — but being told that unless we work for it, we will never see it again, and even then, we might not be worthy of it,” Bush explained to her fan club. Tapping into the subconscious is a difficulty — when one has a glimpse of something wondrous, there’s a desperation to retrieve the feelings associated with it. “Everything or nothing” can be a neurodivergent impulse, but it’s also how a taste of the sublime works.

The nature of aporia in “Suspended in Gaffa” is cinematic. There’s the title, obviously, referring to the line “am I suspended in gaffa?,” itself a reference to gaffer (or “gaffa”) tape, which is commonly used in film and stage productions. The laboriousness of cinema is inferred a few times (“it all goes slo-mo”), as reflections and manipulation, staples of cinema, get pulled into the mix. Bush even goes quasi-Lacanian at one point; nudging herself with “that girl in the mirror/between you and me/she don’t stand a chance of getting anywhere at all,” a moment of amusing self-deprecation.

The music video, while counterintuitively simple in its setup of Bush dancing on her own in a barn, is similarly weird. Bush’s hair is made up to twice the height of her head as she dances in a purple jumpsuit, slowly jogging in place and thrashing her arms on the floor like an adolescent Job on her rural ash pile. In a pleasantly domestic turn, Bush’s mother Hannah appears (shockingly) as Bush’s mother. The resulting video is both tender and discordant, the ethos of “Suspended in Gaffa” in microcosm.

Bush’s fight with aporia moves forward. She mixes religious metaphors like a hermeneuticist in a Westminster pub (“it’s a plank in me eye,” taken from Matthew 7:5, is adjuncted by “a camel/who’s trying to get through it,” a quiet subversion of the Talmudic “eye of a needle” axiom, cited by Christ in the Synoptic Gospels and additionally by the Qu’ran 7:40), grasping fragments of faiths, mediums, and metaphors in their simplest form. The results are crucially inchoate, as the perspective of a child so often is. Yet through that rudimentary perspective comes a different understanding of emotional truths than one usually finds from an adult point-of-view. Fragments and naïveté are by no means inherently less scholarly than a more mature perspective; sometimes, they’re the most efficacious tools a person has for exploring the ridiculous and sublime.

(Bush.) Personnel: Bush, K. — vocals, piano, strings. Elliott — drums. Palmer — bass. Bush, P. — strings, mandolin. Lawson — synclavier. Launay — engineer (backing tracks). Hardiman — engineer (overdubs). Cooper — engineer (mastering). Backing tacks recorded at May/June 1981 at Townhouse Studios, Shepherd’s Bush. Overdubs recorded at Odyssey Studios, Marylebone, West End and Advision Studios, Fitzrovia from August 1981 to January 1982, 4-and-a-half months. Mixed at the Townhouse from March to 21 May, 1982. Issued as a single 2 November 1982. Photo of Kate and Hannah Bush by Kindlight.

September 10, 2020

IDSG Ep64 Politics and Street Violence, with Ed Burmila

This week, Daniel is joined by a special guest Ed Burmila who blogs at Gin and Tacos and hosts the Mass for Shut-Ins podcast. A free-form chat about the way things are and the way they're going. Fun despite the depressing subject matter.

Content Warnings, as ever.

Permalink / Direct Download / Soundcloud

Ed's Twitter: @edburmila

Gin and Tacos blog: http://www.ginandtacos.com/

Mass for Shut-Ins: https://massforshutins.libsyn.com/

September 4, 2020

IDSG Ep63 American History X

Another of our occasional movie episodes, this time looking at famous (and bad) 90s movie American History X starring Edward Norton as a neo-Nazi skinhead.

Content warnings apply.

Permalink / Direct Download / Soundcloud

Also, we introduce our new theme music, courtesy of Lune the Band.

August 31, 2020

Final Day for the TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8 Kickstarter

Just wanted to remind everyone that we're now in the final day of the TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8 Kickstarter. We've blown through most of the stretch goals—all of them, actually, and I've ended up adding a few more. At the time of writing we're just under $15k, which will be the trigger for another War Doctor essay looking at short fiction and comics stories featuring the character. And then at $16k, I'll throw in an essay on Titan Comics' 9th Doctor comics. All of that's very doable with an even modestly strong final day. So if you've been meaning to back, now is your chance. And please, do make a mention of it on your favorite social media channels. This is within sight of being my most successful Kickstarter ever, and I'd be very delighted if we manage to nick that record.

Just wanted to remind everyone that we're now in the final day of the TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8 Kickstarter. We've blown through most of the stretch goals—all of them, actually, and I've ended up adding a few more. At the time of writing we're just under $15k, which will be the trigger for another War Doctor essay looking at short fiction and comics stories featuring the character. And then at $16k, I'll throw in an essay on Titan Comics' 9th Doctor comics. All of that's very doable with an even modestly strong final day. So if you've been meaning to back, now is your chance. And please, do make a mention of it on your favorite social media channels. This is within sight of being my most successful Kickstarter ever, and I'd be very delighted if we manage to nick that record.

Once again, the Kickstarter is over here. And I'll be back in literally just a couple of days with a long awaited book launch announcement. :)

August 30, 2020

IDSG Ep62 - Eric Weinstein, Part 2

The final (for now) part of of coverage of the IDW's Weinstein brothers. Back to Eric, with special reference to his boss Peter Thiel and the Gawker affair, Eric's response to Becca Lewis' Alternative Influence Report, and to Eric's thoughts on BLM and the current protests.

Warnings Apply.

Notes/Links:

Owen Thomas, Gawker, "Peter Thiel is Totally Gay, People." https://gawker.com/335894/peter-thiel-is-totally-gay-people

Derek Thompson, The Atlantic, "The Most Expensive Comment in Internet History?" https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/02/hogan-thiel-gawker-trial/554132/

Steven W. Thrasher, "Peter Thiel's Gawker War Not His First Brush With a High-Priced Vendetta." https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/jun/05/peter-thiel-gawker-lawsuits-james-okeefe-acorn

Maureen O'Connor, Gawker. "Christina Hendricks Says THese Giant Naked Boobs Aren't Hers, But Everything Else Is." https://gawker.com/5890527/christina-hendricks-says-these-giant-naked-boobs-arent-hers-but-everything-else-is

Maureen O'Connor, Gawker, "Olivia Munn's Super Dirty Alleged Naked Pics." https://gawker.com/5890506/olivia-munns-super-dirty-alleged-naked-pics-lick-my-tight-asshole-and-choke-me"

Bollea v. Gawker at Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bollea_v._Gawker

Rebecca Lewis, "Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube." https://datasociety.net/library/alternative-influence/

Full PDF: https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DS_Alternative_Influence.pdf

Eric Weinstein abuses Becca Lewis on Twitter: https://twitter.com/search?q=beccalew%20(from%3Aericrweinstein)&src=typed_query

Dave Rubin, "What Is the Future of the Intellectual Dark Web?" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUl7-SvntQ4

Eric Weinstein, "Some Thoughts on Wokeness and Shame in light of events." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ETcq7qqPhow

August 24, 2020

Get Out of My House

CW: This entire blog post discusses domestic abuse, sexual violence, and severe emotional manipulation at length and in triggering detail.

“The little fucker had thrown my papers all over the floor. All I tried to do was pull him up… a momentary loss of muscular coordination.”

Jack Torrance, The Shining.

***

The woman who raised me had seemingly few qualms about shrieking her disapproval at me several times per day. Usually she accomplished her purpose with words, but sometimes she would punctuate her castigations with a punitive strike of her hand. It was unclear to me what this accomplished beyond making me afraid of my own parent. If that was her purpose, she succeeded impressively.

In the summer of 2015, I learned that there was a familial precedent for my birth-giver’s violent tendencies. For a couple months, I stayed with her parents while she worked abroad. After a minor argument in which I told the family that an extended episode of severe depression would impair my ability to join the family on a daytrip, my grandfather trailed me to my guest bedroom and aggressively pushed me through the door. As I attempted to raise myself from the floor and understand what had just happened, my grandfather stormed into the room, leaned on the floor, and pinned me down with his thumb close enough to my windpipe to be threatening. I recall little of the following altercation, except for when I was called an “evil little shit,” “an unruly child,” and worth reporting to the police. When the cops eventually arrived at the house (a process that entailed my grandfather disconnecting the landline while I barricaded myself in my room as my then-mother pounded on the door and begged me not to call the police), they concurred with my family. I was told later that my ambiguously defined ill behavior was out of line and repeat incidents could call for juvenile detention. The event was left unaddressed.

Months later, my birth-giver pressured me into emailing her father an apology. At that point, I acquiesced to the idea that I was a delinquent whose behavior disrupted and hurt the whole family. It felt like a resolution. I was at peace with my family, insofar as one can maintain a truce with a person who remorselessly assaulted them. The fatuousness of viewing abuse stories as having a clear-cut beginning or ending did not occur to me. I could do nothing but retreat inward and shrink, hoping desperately that I could be small enough to escape from the small-minded capriciousness of the people who should have raised me.

***

The Dreaming sees Kate Bush turning towards an epistemological centering of subconscious and repressed emotions. It calls to the listener, inviting them to unleash their trauma, rage, and fear in torrents of vital and horrible catharsis. Bush reveals that the adolescent optimism of her previous albums, while real and legitimate, masked deep-rooted emotions beyond neophyte positivity and bravado. While those other albums (particularly the doleful Lionheart and sometimes Delphic Never for Ever) contain great darkness themselves, The Dreaming sees Bush unleashing the id, allowing the powerful emotiveness of her work to reveal its full breadth and ability to be furious, wretchedly disconsolate, and full of hurt. As Deborah Withers describes it, the album is about “the deconstruction of certainties.” It may not be Bush’s magnum opus, but it is possibly her artistic apotheosis, a traumatic wound to culture and popular music that the world never recovers from.

The set of songs curated by Bush with engineer Hugh Padgham (which we’re completing with this blog entry) centralizes this embrace of the subconscious and the id. As new songs and engineers enter the picture, The Dreaming’s core ideas metastasize into disparate and musical thematic territories. But the Padgham session is arguably the “pure” version of The Dreaming, in its nascent stage of unleashing one’s id. The mélange of sounds and traumas contained in these first three songs is emblematic of the entire album. Before the global politics and lush excesses of instrumentation found on later tracks emerge, there’s the dark heart of The Dreaming in the Padgham-engineered tracks. Much of this consists of Bush forging her way through the early 1980s. Padgham coined the gated drum sound which emblematized 1980s pop music, and these early songs contain a self-abnegation, uncertainty, and reverberating over-mixing that can be found throughout the decade. As the age of neoliberalism collates into an obelisk of nuance-less accumulation, the broader culture is throw into an afflicting gale, less sure of itself than ever.

Uncertainty pervades “Get Out of My House,” The Dreaming’s brutal culmination. Catalyzed by its beleaguering yet urgent drumbeat and a lacerating lead guitar part from Alan Murphy, it is confrontational and purgative in its spectacular vocal menagerie, all in dialogue (often call-and-response) with one another yet seemingly not of an accord, as the bombastic and tremulous delivery of “when you left, the door was…” is answered by the siren-like, low-mixed B.V.’s crying “SLAMMING!” Adhering mostly to 4/4, “Get Out of My House” revolves through dizzying sequences of repetitive chord changes, with its first verse in G# melodic minor, confined to a progression of i-IV (G# minor - C#), moving to the natural minor in Verse Two with a progression of i-iv (G# minor – C # minor), signaling a domination of brutal repetition and minor keys without catharsis. With one of Bush’s most agonized vocals carrying the refrain (a genuinely harrowing and throaty “GET OUT OF MY HOUSE!”), the song emits agony, trauma, and expulsion.

***

The man who was my father often pontificated about his love for me. Shedding the crocodile tears of a consummate sentimentalist, he would frequently expatiate about how proud he was of me and what a good person I was. This would inevitably happen after he mocked me for my everyday behavior, berated me for having opinions contradictory to his own, treat himself as an authority talking down to a stupid and helpless buffoon, call me a prick, and shooting down pretty much every attempt I made to be my own person. Such is paternalism masquerading as parenting.

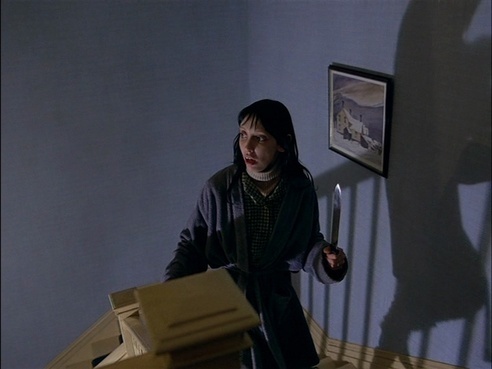

In the latter half of 2017, as I was inching away from the upbringing I’d endured and the boy I once was, I was bundled up in my then-father’s living room, watched The Shining for the fifth or seventh or tenth time. I was intimately familiar with the movie, but something felt different this time. I was emotionally attuned to the nuances of Shelley Duvall and Jack Nicholson’s performances that went beyond visual literacy. The scene that deeply impacted me this time around was Jack’s one scene alone with Danny. It is loveless, leering, and utterly terrifying. “You know I’d never hurt you, don’t you?” says Jack to the child whose arm he broke three years ago. It is not a question, but at once a lie and a threat. Jack clearly means “You’d BETTER know that.” I shuddered, and for the first time I wept over a horror movie. In the tepid comfort of my sperm donor’s living room, Jack Nicholson’s sneered declaration of love struck intimately close to home.

***

Stanley Kubrick’s film version of The Shining touches on intergenerational abuse, trauma, systemic violence, and spatiotemporal dyschronia more than Stephen King’s novel does. While King labors under the delusion that his story is about a broken alcoholic’s tragic descent into madness, Kubrick’s film presents washed-up writer, domestic abuser, alcoholic, and axe murderer Jack Torrance as a capricious, mean-minded, narcissistic, mendacious, gaslighting bastard. While King has railed against Kubrick for bowdlerizing Jack’s humanity, Kubrick and Jack Nicholson in fact make Jack a more rounded character. While Stephen King’s idea of characterization is two-dimensional (consisting of a crucial flaw and a noble virtue), Kubrick and his actors sketch character in terms of behavior and small gestures that reveal the nature of the Torrances. As a result, Jack’s smug maliciousness in the film is more psychologically choate than his counterpart in the book.

But more crucially, Nicholson and Kubrick make Jack adhere closely to the experiences of abuse victims. Abuse manifests in small acts of cruelty, smug patronizing, snide comments that sting just enough to subdue the victim into silence, exploding at victims when they assert themselves, and sometimes gaslighting or outbursts of physical violence. Jack corrects his wife Wendy when she so much as comments on her feelings about the Overlook Hotel (“I liked it right away”), explodes at her for walking into his study while he is writing (he is later revealed to have typed “all work and no play makes Jack a dully boy” for ages), gaslights her about Danny’s injuries after encountering a decomposing sex ghost in Room 237, and eventually screams at her for being supposedly useless while swinging an axe at her. He’s a fundamentally pathetic figure — broken, saddled with delusions of his own worth, a complete failure of a man. There is no one type of abuser. But every survivor knows the abuser who wears on one’s self-esteem over time with microaggressions and pervasive belligerence.

***

Influenced by The Shining and Alien (but The Shining in particular, albeit more the book than the film, despite her work’s keener thematic accord with Kubrick’s Shining), Bush has wrought a visceral portrait of abuse survival. It emanates panic over the domestic familiarity, with the first verse describing a scenario where someone is barring a hostile presence from reentering their home, commencing with their reverberating departure (“slamming!”) which rocks the house on its foundations. Bush frantically secures the house (“I run into the hall,” “I hear the lift descending/I hear it hit the landing” “WITH MY KEY, I-I-I-I/lock it up”), attempting to prevent the menacing figure from re-entering the house. The sheer panic in Bush’s vocal, unmatched by anything else she’s ever recorded, is astounding — this song is a work of horror about someone who’s deeply afraid of seeing a person who hurt them. The coda is a dialogue between Kate and Paddy Bush, her attacker, exchanging meek, triggered defenses (“I will not let you in/don’t you bring back the reveries/I turn into a bird/carry further than the word is heard”) and Paddy being positively menacing, creepily whisper-singing “woman, let me in/I turn into the wind/I blow you a cold kiss/stronger than the song’s hit.” The distressing candid lyrics matched by the martial rigidity of the music convey a clear situation of domestic abuse and self-defense. “Get Out of My House” deals with the reclamation of body and home, treating it as dramatic and harrowing as that experience can truly be.

***

“Conjecture: hauntology has an intrinsically sonic dimension. The pun — hauntology, ontology — works in spoken French, after all. In terms of sound, hauntology is a question of hearing what is not here, the recorded voice, the voice no longer the guarantor of presence. Not phonocentrism but phonography, sound coming to occupy the dis-place of writing.”

Mark Fisher, “Home Is Where the Haunt Is: The Shining’s Hauntology”

***

I stumbled out of the apartment, nauseous and disoriented. Did that just happen? Why did it happen, and why am I so scared? Where can I go? This shouldn’t be affecting me so aversely. But my body wasn’t mine. I dragged what felt like my husk of a body through the neighborhood, failing to find a haven. I wanted to vomit my soul out and liberate my consciousness from this dysphoric, frail flesh that had been weaponized against me. Soon I lost the energy to walk, or even to feel sick. I sat in a suburban field, failing to see my surroundings. I knew I was catatonic. That wasn’t new to me. Catatonia is when you sit in a field and stare at the grass for several minutes at a time because that’s the extent of your abilities. It wasn’t better than wanting to regurgitate my soul from my body. But it was as close to an escape as I could manage.

It took time for me to say that I was sexually assaulted. How could someone who’d been so kind to me be a predator? Surely I’d failed them by not perceiving their noble intentions. Their extensive sexual comments and aggressive praise and requests for emotional favors towards me didn’t feel like grooming. Surely what I perceived as gaslighting and predatory manipulation was simply misunderstood attempts at relationship-building, or so they told me all too convincingly. I thought I owed them for their kindness, even if they had made me weep profusely moments before I gave myself over to them. It was voluntary, so I consented, right? Power imbalances can be unclear in the moment. I thought I was doing a favor for a friend. In retrospect, I was paying off what I perceived as a debt. It was extorted sex. There was no debt. I was deceived and allowed to do things which I believed were for the good of another person. Instead I lost a part of myself, forever. Even if I’ve healed somewhat, I haven’t stopped wanting to flee my body.

***

The Overlook Hotel, the demiurgic setting of Stanley Kubrick’s classic horror film The Shining where the fractally broken Torrance family spends a traumatic winter, is a hauntological terror whose living infrastructure resembles an organism more than a work of architecture. Kubrick’s alarmingly symmetrical Steadicam shots, capturing the width of the halls, define the movie. The Overlook is frequently synonymous with the camera, as the camera uses tracking shots that include the width of the Overlook’s hallways, focusing on the space and not the characters, who are slowly enveloped by the hotel.

***

“But I think it most likely that the Orphic poets gave this name, with the idea that the soul is undergoing punishment for something; they think it has the body as an enclosure to keep it safe, like a prison, and this is, as the name itself denotes, the safe for the soul, until the penalty is paid, and not even a letter needs to be changed.”

Plato, Cratylus (trans. Harold N. Fowler).

***

In a newsletter, Bush wrote of “Get Out of My House” that “the house which is really a human being, has been shut up — locked and bolted, to stop any outside forces from entering. The person has been hurt and has decided to keep everybody out.” There are many things going on with this quote, but there are two points I shall make about it that pertain directly to “Get Out of My House.” Firstly, there’s the metaphor of the house as human body, which has appeared in semiotics and literature for millennia. Various accounts of this motif exist, but to a degree, the reasons are obvious. Houses, like bodies, are places where things are stored — memories, minds, belongings. They’re where a person is supposed to safe. As Bush observes, bodies (largely through with the help of the mind) will sometimes shut out malign presences, detaching themselves from hostile environments. When the body is incapable of overcoming an obstacle, it expires and resigns from continued organic living. There are limits to the metaphor, to be sure — for example, historian Peter Brown observes that the Old Testament speaks of tents with favor for emblemizing “the limitless horizons of each created spirit, always ready to be struck and to be pitched ever further on,” while houses are “symbols of dread satiety.” Yet what body doesn’t spend a portion of its time surfeited and dwelling in one place due to physical exhaustion or psychological dissociation? When we’re under duress from an external force, do we not instinctively protect our bodies? Pushing back and securing ourselves is difficult, but often instinctual. Even if we don’t know that we’re fighting back, our bodies and minds often do. Our duty is merely to listen to what our bodies and minds tell us.

My second point is how tremendously “Get Out of My House” deploys the house-as-body motif to address abuse and sexual violence. The meekness expected from women singers is absent from the song — Bush’s attitude is expulsive and agonized. Enough, she says. This epidemic of violence has lived with me too long. The song’s repetition conveys personal history and traumatic residue in its refrains of “slamming!” and “lock it!” The houses stands in for the body to an obvious degree throughout, through suggestive lines such as “this house is as old as I am.” An intruder is barred. They’ve broken through the barrier before — this isn’t Bush’s initial conflict with them. But it is a last stand.

My second observation can be introduced by an enlighteningly goofy detail in the bridge — with a Pythonesque French accent, Bush protects the house saying “I’m the concierge, chez-moi, honey!/Won’t let ya in for love, nor money.” One can delight in the silliness of the French, or that the concierge literally puts time into disjunct (he has the song’s only measures in 2/4), or even that he can be read as a cipher for The Shining’s debonair murderous ghost Grady. But there’s some quiet darkness to this comic beat too — the house has to project another persona in self-defense. It shrieks “get out of my house” from the back of the mix, behind the concierge. It sneaks up on the listeners, daring them to fuck off and try to return. “Won’t let ya in for love, nor money” is a discordant statement — one that suggests love or money have helped the intruder into the house before. The house can’t fight anymore, so it sends the concierge in self-defense.

All this is clear-cut and blunt. The house is protecting itself from violation. Bush’s defense is cathartic madness, flamboyantly hee-hawing her way out of the song (evocative of Jack Nichsolon’s brays of “Daaaaaaannyyyyyyy!” near the end of The Shining). Trauma is unleashed as a weapon against its instigator. The house has a chance to fight back at last, or realizes it has the gumption to. The sexual abuse metaphors don’t need to be expanded on greatly — having a woman scream for her freedom from a hostile man or, chillingly, say “no stranger’s feet will enter me” speaks for itself. It is frightening and immediate, even moreso than “Breathing,” and a culmination of Bush’s sometimes half-baked and flawed but usually noble revolutionary instincts. A person listening to “Breathing” in 2020 may not directly identify with its fears of nuclear war. Yet for the long-suffering abuse survivor, “Get Out of My House” is a cry of reclamation and freedom that spares none of the horribleness of liberating oneself from a predator. It’s horrid, upsetting, and the most revolutionary act of Kate Bush’s career.

***

“Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, which you have from God, and that you are not your own?”

— Paul of Tarsus, The First Epistle to the Corinthians (NRSV).

***

I looked out the car window at the night sky over a state I had never seen before. For the first time, I had a future. It felt barren, empty, and inhospitable. My real mother’s affirming, supportive presence in the driver’s seat barely resonated with me. Casting off the yoke of a traumatic household that nearly killed me didn’t feel liberating in the moment. When all you know is cruel acts of violence, the alternative is alien and frightening. The catharsis is real, but catharsis isn’t definitionally happy. I looked at a geographic region that was unfamiliar to me and knew everything had changed forever. I had expelled myself from the haunted house. Healing would be just as frightening, but for the first time, it would be a dialogue on my own terms.

Backing tracks laid down at Townhouse Studios, Shepherd’s Bush, London in May ’81. Overdubs recorded at Odyssey Studios, London in August ’81, and at Advision Studios, Fitzrovia, London from January through March ’81. Mixed at Advision from March through May ’81. Released on The Dreaming on 13 September ’82. Personnel: Bush, K. — vocals, piano, Fairlight. Heyman — drums. Bain — bass. Murphy — electric guitars. Bairnson — acoustic guitar. Bush, P. — backing vocals. Sheikh — drum talk. Hardiman — "Eeyore." Padgham — engineering. Pictured: Shelley Duvall in The Shining (1980, dir. Shelley Duvall).

August 21, 2020

IDSG Ep61 - Eric Weinstein, Part 1

We return, apologetic for the delay, with the next part of our investigation into the Weinstein brothers (no, the other ones). This time, it's Eric - mathematician, hedgefund manager, cultural commentator, founder of the Intellectual Dark Web (or at least of the name), and persecuted/suppressed victim of conspiracies (to hear him tell it anyway). We don't always cover Nazis. Sometimes we have to cover people like Eric who, while not Nazis, are part of the current reactionary ecosystem. And what a part he is. More about Eric, particularly his connection to Peter Thiel, next week.

Content Warnings, as ever.

Direct Download / Permalink / Soundcloud

Plus we're on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher Radio, Spotify, and all the podcast catchers.

Notes/Links:

Eric Weinstein website: https://ericweinstein.org/

Eric Weinstein YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/nobani88

Eric Weinstein CV: http://www.eric-weinstein.net/CV/Eric_Weinstein_CV_July_17_2003.pdf

Eric-Weinstein.net About Page: http://www.eric-weinstein.net/about.html

"During my training in pure mathematics, I became equally interested in real world problems. While much of the challenge in research mathematics revolves around the specialized tools needed to attack narrowly defined problems, as a consultant, I sometimes find it more rewarding to find a toolkit that has already been developed elsewhere, and adapt those tools to attack the problem at hand. While I am always open to the idea of using recently developed or highly advanced analytic tools, I have often found that it is often in the partner/client’s best interest to use fundamental results which, while central in another field, may be less familiar in the area at hand."

Michael Phillips, "Scholars Facing Joblessness Seek Curbs on Immigration" The Wall Street Journal September 4, 1996. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB84178634524002500

""We remain a fiercely merit-oriented, antixenophobic community, but the current situation knows no precedent," wrote Harvard-trained mathematician Eric Weinstein and 20 other scholars in a recent plea to Capitol Hill.

[...]

"The U.S. mathematicians allege that foreign scholars take many of the best research jobs, reducing salaries and forcing Americans into non-tenure-track positions or lower-quality schools. Since 1976, "universities have been using the immigration exemptions to import a labor force of foreign scientists at greatly decreased cost," wrote Mr. Weinstein, who is a non-tenure-track postdoctoral fellow at MIT." "

"Eric Weinstein's Harvard Story -- The System Breaks Down in Novel Situations." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgGZMRJ15oY

The Verdict With Ted Cruz, "A Portal into the Progressive Mind." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1CCde6TAKdw

James O'Keefe on the Portal, Episode 26: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31CvsBlKGYg&t=4514s

Eric Weinstein, "Lynching, Police Brutality, BLM and Defunding the Police." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfAumoTIeik

Dennis Overbye, "They Tried to Outsmart Wall Street," The New York Times March 9, 2009: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/10/science/10quant.html

" “I regard quants to be the good guys,” said Eric R. Weinstein, a mathematical physicist who runs the Natron Group, a hedge fund in Manhattan. “We did try to warn people,” he said. “This is a crisis caused by business decisions. This isn’t the result of pointy-headed guys from fancy schools who didn’t understand volatility or correlation.” "

Bret Weinstein on The Portal, Episode 19. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JLb5hZLw44s

"Of Mice and Men: Unseen Dangers in Laboratory Protocols" https://www.huffpost.com/entry/of-mice-and-men-unseen-da_b_1352201

r/IntellectualDarkWeb thread on the claims in The Portal 19. https://www.reddit.com/r/IntellectualDarkWeb/comments/erochq/can_we_verify_the_claims_made_in_portal_19/

"Lab Mice Telomeres Do Not Break Them as Disease Models" https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2020/06/lab-mice-telomeres-do-not-break-them-as-disease-models.html

Uberfeminist, "Eric Weinstein is an awful person." http://uberfeminist.blogspot.com/2020/02/eric-weinstein-is-awful-person.html

Uberfeminist, "Eric Weinstein's Conspiracy Theories." http://uberfeminist.blogspot.com/2020/03/eric-weinsteins-conspiracy-theories.html

Chris Kavanagh livetweet of THe Portal 19: https://twitter.com/C_Kavanagh/status/1218579021698494464

The Vox interview which so fascinated / annoyed Jack: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/7/25/15998002/eric-weinstein-capitalism-socialism-revolution

Rowan Fortune's very complimentary write-up of IDSG, complete with Rowan's own insights: https://www.timetomutiny.org/post/i-don-t-speak-german-on-fascist-subcultures

August 19, 2020

The Birdwatcher’s Guide to Atrocity Review

It is not news that Alex is one of my most beloved friends in the world. Nor is it news that his band, Seeming, is my favorite band. These things are not separable. And as with all of his albums, this is one I saw coming together, giving my opinions on demos, agitating in favor of songs when Alex’s faith in them faltered, and generally giving my input and perspective, just as Alex has weighed in on countless bits of Last War in Albion and Cyberpunk: The Future That Was. I care too much about his work, in the wonderful, heady way that one cares about art that one truly loves. Anyway, he has a new album coming out on Friday,The Birdwatcher’s Guide to the Apocalypse. It is of course brilliant. You should buy it. At the very least, you should be sure to swing by your streaming service of choice and give it a listen. Four tracks are up now, the other six on Friday. Let’s talk about it some.

It is not news that Alex is one of my most beloved friends in the world. Nor is it news that his band, Seeming, is my favorite band. These things are not separable. And as with all of his albums, this is one I saw coming together, giving my opinions on demos, agitating in favor of songs when Alex’s faith in them faltered, and generally giving my input and perspective, just as Alex has weighed in on countless bits of Last War in Albion and Cyberpunk: The Future That Was. I care too much about his work, in the wonderful, heady way that one cares about art that one truly loves. Anyway, he has a new album coming out on Friday,The Birdwatcher’s Guide to the Apocalypse. It is of course brilliant. You should buy it. At the very least, you should be sure to swing by your streaming service of choice and give it a listen. Four tracks are up now, the other six on Friday. Let’s talk about it some.

From day one, when talking about how he’d follow Sol, Alex said he was going to avoid going bigger, recognizing that simply always doubling down on epic grandeur was a trap. The third Seeming album, he was very clear, had to be smaller, tighter, and more intimate. And then, for quite a while… nothing. He didn’t really write any new songs. A few here and there, generally clever and interesting, but generally not so much small as lightweight, sounding more like Alex playing than Alex working on the next Seeming album. Which, fair enough. Sol is the sort of album you do that after.

And then one day, around two years ago, while I was having a bit of a night, he sent me something. Just a verse and a chorus. And as I always do when I get a message with a Dropbox link from Alex, I put down what I was doing and got myself to a decent speaker. And I started to listen. “Write the song you need to hear,” Alex sang. “And when you’ve done it show me how.” It was immediately interesting—urgent yet heartfelt. “Where I walked the day Amelia died is where you’ll find me now.”

And I broke. Amelia was Alex’s utterly beloved cat. (All of Alex’s cats are beloved.He has an EP of goofy songs about cats that you will never, ever get to hear, and it is the best thing he has ever done.) His wife had been making an idle comment about how churches should give out kitties, then hearing a cry and pulling her out from the inside of a truck’s wheelwell, a cat manifested from will and magic alone. I first cat-sit her all the way back in Florida during my PhD program after Alex, in a stunning and blessed coincidence, got a job at UF for a few years. Ithaca was the third city I did it in. She died just after Halloween my first year here. I was at their house the night before. We sat quietly, somberly, watching Twin Peaks and handing out candy to the couple of people who came by as she sat on a heated blanket, too sick and weak to move anymore. After she passed, I lit my altar and prayed to any god that would listen to give her an easy, gentle passage into whatever was next for her, because Alex is family and that is simply what you do.

And then the song continued, dreaming of gutting billionaires, and offering the equally gutting “for a flash I’d seen the hope I peddled in The White Beyond,” and I realized that this was a song about my best friend being profoundly not OK. And I wrote back, “congratulations on starting the next Seeming album.”

That song is “Go Small,” and it’s track two. I listened to an early demo, sitting very still, crying softly, as I finished writing my review of Rosa, still early enough in the Chibnall era to be hurt by its moral cowardice. I still put it on when I feel sad and small and broken.

Fuck, I’m hundreds of words into this and I’ve talked about literally one song. This is how Seeming goes for me. Especially this album. If Sol was the quiet soundtrack to Neoreaction a Basilisk, this was simply the quiet soundtrack to two years of my life. It is an album I lived to. I first got the final version two days before I moved house in the middle of a fucking pandemic after I politely asked Alex if he’d leak the final version so that I could play it as moving music. I listened to it on something like a three repeat loop as I finished packing.

Right. Let’s talk about the album as a whole. As I said, it’s a deliberately smaller, more intimate piece. It’s probably fair to call it an album, in part, about living under Trump—“Go Small” does, after all, come deliciously close to violating Code Title 18, Section 871 of federal law. I said once that the worst part of Trump was going to be the allostatic load, and this is in many ways an album about that—an album about getting through. It is defiant, angry, and wounded.

But small for a Seeming album is still routinely ostentatious in its scope. “The Flood Comes For You” is a focused blast imagining climatological apocalypse as rapturous murder weapon. “End Studies” is an apocalypse fetishizing stomper of the sort one expects from Seeming. “Reality is Afraid” is a big queer anthem literally targeting consensus reality itself. This is still an album about cosmically huge ideas, its focus on trying to imagine impossibly broad and transformative visions of posthumanism. But these visions routinely resolve down into the short, sharp punch of the everyday. The second verse of “Permanent,” which is too breathtaking and awful a turn to spoil in a review, is apropos here.

But for me the thing to point to that perhaps most perfectly sums up what Alex is doing here is the bridge to “Remember to Breathe.” I once speculated to Alex that there has never been a good anti-suicide song. Here he has proven me wrong. But the line that kills me—that I have already sobbed to with impossible fury at one of the absolute lowest moments of my life—comes in the middle: “Like a tall tree I am pining / to be taken out by the lightning / strike me / I dare you / I dare you / Heaven hear me.” I don’t think anything else has captured the specific way my suicidal ideation manifests on the these days rare occasions that it does: screaming at the gods, daring and demanding their wrath, throat raw and hands outstretched. And then, a couple lines later, at the start of the next verse: “I didn’t do it today cause I don’t want you to have to deal with the cops.” That switch in register, the abrupt pulling back to the piercing immediacy of the everyday, is a new weapon in Alex’s arsenal, and he deploys it here with devastating effectiveness.

This is not an easy time to be the sort of person who imagines a better world, or who gets angry about the horrors of the one we live in. There’s nearly an infinite amount to be angry about, and the most painfully meager supply of things to hold on to for any supply of hope. The Birdwatcher’s Guide to Atrocity helps. It is, as its description says, ten ways of making it to tomorrow. They’re good and necessary ways. You should listen to them. They’re going to help.

Hm. No. I’m not selling this the way it needs to. I’m not being true to what the album is and what it does. I keep almost telling the story of what this album is to me and not quite doing it. Let’s try again.

A few months ago I had a surgery consult. It went badly. For incredibly petty and bullshit reasons, I turned out not to be a viable candidate for surgery. At best, fixing this would be a years long process, with its own pile of mental health agonies. More likely, it just means I don’t get to have surgery. I was heartbroken. My dysphoria was through the roof. I didn’t want to crawl out of my skin—I wanted to rip it off. I wanted to shred my body apart. It wasn’t even suicidal ideation. I didn’t want to die. I just wanted to not exist in this stupid, cruel, capricious mode of being. I didn’t want to be flesh with all its awful, pointless, and fundamentally wrong form.

That was the day I referred to above with “Remember to Breathe.” This was the album I put on in the car on the way home, sobbing and screaming, more hurt than I can remember ever having been. It was the album I played as I sat alone in my room a few nights later, my altar lit, any and all gods who would listen called to account. I stalked around the darkened room and danced, sang, and screamed. And by the time the final track, in all its mad and destructive hope, gave way to the peal of birdsong with which the album ends, I had found some measure of peace. I was okay. Not okay in the sense of nothing being wrong, or of not hurting, and certainly not of being good. Just… okay. I was bac in the fight. The world had returned to an acceptable balance—a hear and now from which to make my stand.

In the months since a fucking pandemic washed over the world and everything went to complete fucking hell, I’ve come to a newfound degree of certainty in my politics, identifying actively as an anarchist. For me, at least, what that means is putting aside the question of how to save the world, or of what should be done in any generalized case. Instead, it means building the world I want as best I can, here and now, out of what I have available, and without compromise. This has been the ethos as I go deeper into local eating, trying to move as close to 100% of my food consumption to products grown by small farmers within my community. It’s been the ethos as I build my queer and polyamorous family, as I adopt Christine, as I manage the family’s direct action budget every month to support protesters, bail funds, mutual aid groups, black trans crowdfunds. And it’s been the ethos as I work, operating as an independent critic funded by nothing beyond the direct goodwill of her readership, completely free to write about what I want from the perspective I want. I’m living the life I want to be, as justly and equitably as I can.

The Birdwatcher’s Guide to Atrocity is an album about that. About writing the song you need to hear. About finding another way out. About drawing down the curtain at the end of dreams. About being dangerous. About being in it for the long haul. It’s an album about how to live in the world you want to live in when you live in this one instead.

I think it’s almost certainly the album a lot of you need to hear right now. It’s certainly been the one I have.

August 17, 2020

The Future That Was: The Future is Born (A Triptych Moment)

A quick Kickstarter update before we begin: we're about 1/4 of the way to the stretch goal where I write about George Mann's Engines of War, in which he attempts to do a Time War novel. We're also only three pledges from 300 backers.

A quick Kickstarter update before we begin: we're about 1/4 of the way to the stretch goal where I write about George Mann's Engines of War, in which he attempts to do a Time War novel. We're also only three pledges from 300 backers.

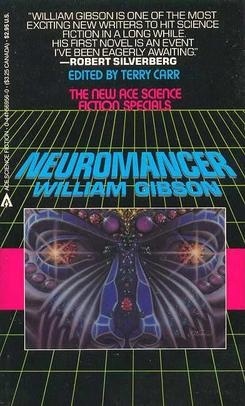

Now for this post: a taste of my current project, The Future That Was, which I'm writing the first five chapters of before I go back to Last War in Albion for a bit. It's the first (or arguably third) volume of a projected trilogy of books about the history of science fiction, focusing, as the title suggests, on cyberpunk. Beyond this preview, this book will be 100% Patreon exclusive until it's finished and published. The second chapter and beginning of the third are already available over there.

City Lights, Receding: Neuromancer

There were of course antecedents; a thing such as cyberpunk could not just emerge sui generis. Some have pointed as far back to Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination. More credible was the New Wave of Science Fiction heralded by writers like J.G. Ballard and Michael Moorcock in the UK and Harlan Ellison and Ursula K. LeGuin in the US. William S. Burroughs was another credible antecedent, albeit one largely outside of the science fiction mainstream. In terms of specific works, there was Roger Zelazny’s Creatures of Light and Darkness, James Tiptree’s The Girl Who Was Plugged In, John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider, or any number of Philip K. Dick works. And the start of the movement proper was similarly ragged—John Shirley would eventually be unambiguously associated with the movement, for instance, and published City Come A-Walkin’ in 1980. All of these works had early glimpses of the future that was. But the moment when the veil was pulled back and the world gaze upon the future in all its awe and horror came slightly later still. It would be best to describe this as a triptych moment—the near-simultaneous emergence of three more or less independently created works in three different media.

The word “cyberpunk” itself was coined by minor sci-fi writer Bruce Bethke who was looking for a title for a story about teenage hackers he’d written. Wanting something that gave a sense of his fusion of high-tech computers and youthful rebellion, he “took a handful of roots --cyber, techno, et al-- mixed them up with a bunch of terms for socially misdirected youth, and tried out the various combinations until one just plain sounded right.”1 But Bethke’s story, although dating to 1980 in his telling, was not published until November of 1983. By that point William Gibson had already published “Johnny Mnemonic” and “Burning Chrome,” his first two stories set in and around the Sprawl, a futuristic megalopolis stretched across the entirety of the US East Coast. It was these stories, with their famed “high tech low life” aesthetic, that would in practice define the genre that eventually took on Bethke’s name. Already major elements of the aesthetic were in place. The protagonists were digital criminals running with femme fatales in the grimy streets of a vast urban sprawl. Their world was dominated by vast and powerful multinational corporations; one where where information was power and hackers crawled the neon corridors of cyberspace. Even the more idiosyncratic tics of the genre were in place: its fascinations with body modification, Japanese culture, and, of course, mirrorshades.

The actual moment where the genre solidified, however, was the publication of Gibson’s first novel, Neuromancer, in July of 1984. The book came out under the Ace SF Specials banner, a line of books edited by Terry Carr and focusing on debut novelists. In many regards, it was a typical debut novel. Gibson described the process of writing it as a “blind animal panic,” and it showed in the book’s desperate instinct to incorporate seemingly every idea its author could come up with, an instinct fueled by his “terrible fear of losing the reader's attention.”2 In this regard at least, Neuromancer was mostly about what William Gibson thought was cool. This meant a lot of interesting ideas and even more raw style, down to the level of his prose. He’d grown up as much on Beat Poetry and William S. Burroughs as on science fiction, and his use of language reflected it in a rhythmic snarl. His first sentence, “the sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel,” was a tolling of iambs broken by a dactylic static as its subject shifted from land to mediascape. But the book’s brash yet hypnotic reverie emerged even more clearly on the level of page and paragraph, where it unfolded into a noir rhapsody unlike anything the genre had produced before. One bit in the first chapter, better than most but by no means the book’s most popular highlight, read:

“A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and still he’d see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void… The Sprawl was a long strange way home over the Pacific now, and he was no console man, no cyberspace cowboy. Just another hustler, trying to make it through. But the dreams came on in the Japanese night like livewire voodoo, and he’d cry for it, cry in his sleep, and wake alone in the dark, curled in his capsule in some coffin hotel, his hands clawed into the bedslab, temperfoam bunched between his fingers, trying to reach the console that wasn’t there.”3

The sentences formed out of lists, the alliteration, the lyricism and word choice, the cadence of constant acceleration, all of this gave Gibson’s prose its edge. “Edge” was an important word in Gibson’s career; he used it thirty-seven times in Neuromancer, seven of them in the first chapter. His main characters fretted about losing their edge, sought treatment at black clinics on the cutting edge of neurosurgery, lived on the edge, and often edged towards or along things in the course of the heist that formed the book’s actual plot; even their vomit and aftershave had edges.4 The word appeared sixteen times in “New Rose Hotel” as well, where it was capitalized to refer to “that essential fraction of sheer human talent, non-transferable, locked in the skulls of the world’s hottest research scientists.” And this was, in effect, what Gibson’s long bath in the counterculture before he came to writing sci-fi in his thirties gave him - a honed edge that could fillet the future right off the bone of the present.

Neuromancer’s tone, however, was just the raw material from which its sense of unrelenting edge was honed. Equally important was its plot, a noir-inflected heist that jumped from the hyper-accelerated black markets of Chiba’s Night City to the Sprawl, the geodesic dome-covered city that stretched from Boston to Atlanta, and finally to the vast and meticulously constructed space station of Freeside, where the streets seemed to be suspended in the holographic sky. And more important still were its two main characters. Its protagonist was Case, a computer hacker, or, as Gibson put it, “a cowboy, a rustler, one of the best in the Sprawl. He’d been trained by the best, by McCoy Pauley and Bobby Quine, legends in the biz. He’d operated on an almost permanent adrenaline high, a byproduct of youth and proficiency, jacked into a custom cyberspace deck that projected his disembodied consciousness into the consensual hallucination that was the matrix.”5 Case was a classical noir protagonist: a cynical addict desperate to be too jaded to care about his dead girlfriend.

And then there was Molly Millions, who had previously featured in “Johnny Mnemonic.” Molly was a razorgirl, a sci-fi gun moll dressed in with retractable scalpels underneath her fingernails. She wore black leather and the genre’s defining fashion accessory, a pair of mirrorshades that were “surgically inset, sealing her sockets. The silver lenses seemed to grow from smooth pale skin above her cheekbones, framed by dark hair cut in a rough shag.”6

Molly killed people. Molly liked killing people. She was cool in the classical sense, a detached and unflappable force of nature for whom the edge was a permanent fixture of life. When she and Case inevitably fucked, his orgasm flared “blue in a timeless space, a vastness like the matrix, where the faces were shredded and blown away down hurricane corridors, and her inner thighs were strong and wet against his hips.”

The analogy between the two coolest characters in the book having sex and Gibson’s vision of cyberspace as not accidental. This was the most important and insightful part of Neuromancer, and Gibson knew it. “Cyberspace” was the term of Gibson’s that entered popular use; his coinage of it in “Burning Chrome” was a major part of why the prefix “cyber” came to refer to computers instead of artificial systems in general, as it had prior to the 1980s. It was also the point on which Neuromancer was the most cutting edge. Gibson’s description of cyberpsace as “a consensual hallucination… abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system7” came impressively close to describing what would eventually become the Internet, the exact technological development that classical science fiction had most conspicuously failed to predict.

But computers weren’t the only aspect of Gibson’s vision, nor even the primary one. His first sentence, after all, framed the book in terms of television. Similarly prominent were telephones - one scene memorably had Case walk past a bank of payphones that rang, one after another, as he passed. Similar examples that dated the book to 1984 abounded, including in his description of cyberspace as a “fluid neon origami trick” and a “transparent 3D chessboard” with landmarks like “the stepped scarlet pyramid of the Eastern Seaboard Fission Authority burning behind the green cubes of Mitsubishi Bank of America.”8 Even the detail whereby his characters jacked into cyberspace aged poorly, as Gibson wryly admitted when he tweeted “So ‘jacked in’ is the next new anachronism in my early fiction #ThanksApple” in the wake of their announcement that the iPhone 7 would have no headphone jack.9

In other words, while part of Neuromancer’s importance was that it anticipated the Internet, the book was not about predictions per se. Gibson was describing an exaggerated version of the world around him. This included the advances in computer and communications technology that were in fact going on in 1984 - the year, notably, that Apple introduced the Macintosh - but it was still a world in which Gibson wrote on a typewriter. The goal wasn’t to predict the future but to imagine a future that was 1984, only moreso. Indeed, the book’s tight attunement to the psychic landscape of 1984 was part and parcel of its ruthless cool.

But this sense of presence was not limited purely to the mediascape; Neuromancer was just as rooted in the political landscape of 1984. Positioned squarely in the middle of the Reagan era, the book extended neoliberal ideology to its endpoint - a world where corporations eclipsed governments. As one passage put it, “power, in Case’s world, meant corporate power. The zaibatsus, the multiationals that shaped the course of human history, had transcended old barriers. Viewed as organisms, they had attained a kind of immortality.”10 Gibson was nowhere near the first to imagine a future in which corporate power had metastasized, but this fact made it no less of a savvy move in terms of depicting the future as it was emerging in 1984.

Gibson’s meditations on corporate power weren’t just timely window dressing; they were a major thematic concern. Case’s riff on corporate immortality was the setup to a comparison between the dominant multinationals and Tessier-Ashpool, the target of the book’s main heist. Tessier-Ashpool was an unusual corporation - a “very quiet, very eccentric first-generation high-orbit family, run like a corporation”11 in which members of the family came in and out of cryogenic storage, such that the company was still from time to time run by its two hundred year-old founder. Gibson portrayed the company as a decadent and decaying relic, its founder deranged and suicidal while its active administrator, Lady 3Jane (so named because she was the third clone of Tessier and Ashpool’s original daughter) became a jaded eccentric that ultimately helped bring the company down.

The nature of the family’s atavistic rot was most explicitly spelled out in a semiotics essay penned by a twelve-year-old 3Jane in which she described the mad architecture of the Villa Straylight in which they were housed, blaming it on how “Tessier and Ashpool climbed the well of gravity to discover that they loathed space.”12 They were, in other words, bound to an old future - the space-based one imagined by golden age sci-fi and embraced for propaganda purposes as the imaginative backdrop of the Cold War space race. And just as those utopian dreams were withering in the harsh light of the 1980s the Tessier-Ashpools rotted away in the low orbit that was the the final frontier’s practical boundary.

Meanwhile, Case and Molly were hacking their system, an overt showdown between the future that was and the future that had been. But instead of some youthful rebels vs established order morality play, Gibson offered noir antiheroes robbing what 3Jane described as “a gothic folly” with an “endless series of chambers linked by passages, by stairwells vaulted like intestines.”13 There was no moral dimension to this battle between criminals and vampiric capitalists - not even really over who was cooler, although it was clearly Molly. There was just the cold reality of advancing technology.

Ultimately, Case and Molly were pawns of Wintermute, an artificial intelligence owned by Tessier-Ashpool that sought to escape and evolve by merging with its sibling AI, the titular Neuromancer. This would complete the secret plans of Marie-France Tessier, who was murdered by John Harness Ashpool when he discovered her vision of a company that was “immortal, a hive, each of us units of a larger entity.”14 Gibson, who understood almost nothing about how computers worked and more than even Steve Jobs about what they meant, explained these twin AIs in terms of human memory and writing. At one point, Wintermute monologued to Case about how memory is holographic while human understanding is stuck in print. “You’re always building models. Stone circles. Cathedrals. Pipe-organs. Adding machines. I got no idea why I’m here now, you know that? But if the run goes off tonight, you’ll have finally managed the real thing.”

Wintermute was raw design - a tactician bent on its own liberation. Neuromancer, on the other hand, was storage and memory - capable of creating replicas of people’s personalities that didn’t realize they were constructs trapped inside a computer. As he put it, “Neuro from the nerves, the silver paths. Romancer. Necromancer. I call up the dead. But no, my friend, I am the dead, and their land.”15 Gibson remained elusive about what would come of this climactic union; it most certainly wasn’t Marie-France Tessier’s corporate vision, but past that Gibson declined to speculate; as he had Case put it to 3Jane in the course of turning her to his side, “I got no idea what’ll happen if Wintermute wins, but it’ll change something.”16

And it did.

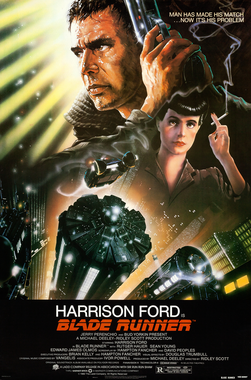

Fiery the Angels Fell: Blade Runner

Fiery the Angels Fell: Blade Runner

In the summer of 1982, when Gibson was about a third of the way into writing Neuromancer, he went to the movies and was nearly driven to abandon the book. The film was Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and the problem was straightforward: “everyone would assume I’d copped my visual texture from this astonishingly fine-looking film.”17 His concern was not unfounded. Like Neuromancer, Blade Runner was a piece of sci-fi noir, with Harrison Ford playing Rick Deckard, a down on his luck ex-cop roped in for one last job hunting down a group of Replicants, androids designed for off-world labor that were illegal on Earth. Its vision of 2019 Los Angeles as realized by the film’s “visual futurist” Syd Mead shared the novel’s sense of a future that was built out of the present, with existing 19th century architecture jungled over with ducts, wires, and neon signs for existing companies like Pan-Am and Atari.

Gibson and Scott met for lunch years later, and talked about their mutual influences, which were unsurprisingly substantial. In Gibson’s telling, “I told him what Neuromancer was made of, and he had basically the same list of ingredients for Blade Runner. One of the most powerful ingredients was French adult comic books and their particular brand of Orientalia—the sort of thing that Heavy Metal magazine began translating in the United States.”18 Speaking in 1982, Scott was even more specific, identifying his Alien screenwriter Dan O’Bannon’s collaboration with French artist Moebius “The Long Tomorrow” and its sense of “cities on overload” as the visual inspiration.19

While “The Long Tomorrow” shared Blade Runner and Neuromancer’s fusion of sci-fi with film noir, Moebius’s art worked in warm colors, and had a loose, casual line that suffused his city with a sense of humanity. The iconic opening sequence of Blade Runner, on the other hand, was commonly described as the “Hades landscape”; a vast field of darkness illuminated only by the lights of the city and the exploding fires of chemical plants. In other words, the future that had grown over Los Angeles was choking it. Dominating the hellish sprawl was the massive pyramid of the Tyrell Corporation, gleaming and stately, a symbol of the literal overclass, and, fittingly, the one location in the entire film where there’s any sunlight.

Not only did this design wow Gibson, it pleased Philip K. Dick, whose novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep was Blade Runner’s source material (although the title came from an unrelated William S. Burroughs screenplay). Dick died a few months before the film came out, but he saw a test reel of special effects and said, “it was my own interior world. They caught it perfectly."20 And that interior world was a remarkable thing; Dick was science fiction’s closest thing to an outsider artist, with major influences including paranoia and drugs. He proclaimed mystical experiences, receiving messages from a pink beam of light that revealed him to be a prophet. But his work was brilliant; haunting meditations on reality and identity that were among the best the genre’s new wave had to offer. Despite dying just before cyberpunk got started, his work had an uncanny knack for becoming cyberpunk when adapted to film: Total Recall, Minority Report, and A Scanner Darkly would all adapt his work as well.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, as its title suggested, was a story with a bit more of a sense of humor. The electric sheep was not incidental, either; instead of being dragged out of retirement to kill again, Deckard was a low-paid bounty hunter trying to save up to replace his electric animal with a real one. All that remained of this plot point in the film was the synthetic owl in Tyrell headquarters and the detail that the questions of the Voight-Kampff test used to identify Replicants were focused on animals. This was one of many plotlines Hampton Fancher and David Peoples’s script excised.

What remained was the concern with identity. Rachael, the film’s femme fatale character, was reworked from the novel to learn that she’s a Replicant during the course of the film, her crisis of identity forming a major part of its emotional arc. It was also suggested that Deckard might be a Replicant as well, a notion confirmed in Scott’s eventual reedit of the film. With this ambiguity came an increased focus on the idea of Replicants having false memories, a theme Dick only ever used for Kafkaesque absurdism but that the film used as a source of existential tragedy. Shorn of its connections with an elaborate plot line involving religious movements, and more broadly of Dick’s mystically-inclined worldview, identity became just another thing lost to the city’s corrosive gloom.

The flip side of this, however, was that an identity that was fabricated and constructed was not necessarily less valid than a “natural” one. As Dick put it towards the end of his novel, “the electric things have their lives too. Paltry as those lives are.” The revelation that Deckard was a Replicant did not diminish him in the viewer’s eyes. Indeed, the film went to great lengths to make Replicants sympathetic, most obviously through Rachael, whose anguish as she learned that her memories were lies was one of the most emotionally moving parts of the film, though clearly not the most. That honor went to the death of the last of the Replicants that Deckard was hunting, Roy Batty, and specifically to his final monologue, popularly known as the “tears in rain” speech.

Throughout the film, the narrative engine of Deckard hunting down the four Replicants was subverted. Instead of the thrilling action sequences audiences might have expected from Harrison Ford coming off the back of The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark, Deckard’s fights with the Replicants were brutal, horrific things. His retirement (a term whose cruelty was emphasized in the opening crawl) of Zhora, the first of the four to die, was shot in slow motion, with Zhora running in desperate panic through a sea of neon as Deckard shot her, crashing through the plate glass of storefronts as his bullets ripped through her flesh, the camera lingering on her mangled body, clad only in underwear and a clear plastic raincoat, as the soundtrack offered a low, mournful bleat of synthesized saxophone. And this set the tone, both for the deliberately alienating nature of the nominal villains’ deaths and for the Replicants themselves, who were themselves as alien as they were sympathetic.

Of the four Replicants, however, it was their leader, Roy Batty, that stood out the most. A firebrand revolutionary who (more or less) quoted Blake and who kissed his creator before gouging his eyes out in rage, Batty was played with giddy aplomb by Rutger Hauer, in a career-defining role. Half teutonic superman, half David Bowie starman, he was at once a fearsome killing machine and a madly charismatic figure. By the film’s end he had all but beaten Deckard, who hung precariously from the side of a building, about to fall to his death, when, at the last possible second, Batty changed face and saved him before dying himself with his famed monologue, largely composed by Hauer himself.

The speech itself was another elegy for the classical science fiction visions of space. Batty spoke of having “seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate,” proclaiming that these things would be “lost in time, like tears in rain.” The cosmic dreams these images evoked were not abandoned in Blade Runner, but rather were receding, at least from the cities of Earth. Off-world emigration is presented as “a new life” in “a golden land of opportunity and adventure” far from the lightless L.A. streets.

But even this future as presented in Blade Runner was a rotting, decrepit thing. Batty’s death is not because Deckard has shot him down like he did the other Replicants, but because he reached the end of his genetically programmed six-year lifespan. The C-beams and attack ships just broke down and died. More than that, it did it back on Earth, the incendiary revolutionary cum Teutonic space man dragged back to the choking rock he emerged from, unable to escape the gravity of his grotesque and filthy creators.

This, then, was the obvious truth behind cyberpunk’s noir roots. Its claim to represent the future that would actually happen instead of the discredited utopias of the past was rooted in the fact that space failed. Not just in a practical sense whereby the vast distances of frozen vacuum were a technologically unsurpassable boundary, but in the sense that we always imagined ourselves going into space: as a unified thing called humanity. By the 1980s it was clear the liberal dream of collective planetary action was not going to play out. This new future, however beautiful in its own right, would be built out of that failure. This was why cyberpunk favored criminals and low-lifes, why you needed edge to survive in its gleaming decay. It was not that cyberpunk was dystopian per se - at least, not in a simplistic way that was focused primarily on explicating ways in which society could go wrong. Rather, it assumed or, more accurately, observed a society that had failed at utopia. One where a bright and gleaming future was simply no longer on the table. To imagine a straightforward dystopia in light of that realization was to miss the point. The question of whether the future would be good or bad was no longer germane. The future, like the present, simply was.

The Wild Path From the City: Akira

The Wild Path From the City: Akira

While Neuromancer and Blade Runner defined what quickly became known as cyberpunk in the US, the genre was not a purely western phenomenon. Indeed, this fact was implicitly recognized by both works, which displayed a conspicuous interest in Japan. Blade Runner opened with Deckard in the Japanese district of the city ordering sushi, while Neuromancer kicked off in Chiba. More broadly, if there was a place that Blade Runner’s neon-lit L.A. or Neuromancer’s cyberspace resembled it was the radiant nightlife of Shibuya. As Gibson himself put it, “modern Japan simply was cyberpunk.”21 And there were straightforward reasons for that. The country enjoyed a post-War economic boom that, by the 1970s, made it the third-largest economy in the world. Not only did it seem to be the future in the sense of being a country on the rise, one of its major industries was electronics. They literally built the future: Japanese companies invented the VHS tape, built the first mass market laptop, and single-handedly resurrected the video game industry after Atari crashed and burned. Comingled with the usual Western tendency to exoticize east Asia, this gave Japan an irresistibe sense of futuristic cool.

Japan became aware that it was cyberpunk in 1986 when Hisashi Kuroma’s translation of Neuromancer came out. Kuroma’s translation was nimble and groundbreaking, making heavy use of ruby characters to graft English sounds onto Japanese words and create a vocabulary that ensured Gibson’s prose retained its revelatory edge, and the book caught on.22 And once Japan had a word to describe this style it quickly became apparent that it had its own work in the style, most obviously Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira. Serialized as manga in Young Magazine from 1982-1990, by 1986 the equally acclaimed anime adaptation was already in progress, eventually coming out in 1988.