The Last War in Albion Book Two, Chapter Eleven: By Another Mans (Look Upon My Works Ye Mighty)

Quick update on Christine's Patreon. There's been a tremendous response, but she's stalled at around $208 at the time I'm writing this on Saturday. Financial security for her really needs about $300, so if you're at all interested in her amazing Kate Bush work, please check it out. Also, she's got fun intermediate goals: at $225 she'll be doing a podcast with Daniel Harper, and at $250 another with Jack Graham about Alien and The Shining. So please, help my daughter afford an apartment via her Patreon.

Quick update on Christine's Patreon. There's been a tremendous response, but she's stalled at around $208 at the time I'm writing this on Saturday. Financial security for her really needs about $300, so if you're at all interested in her amazing Kate Bush work, please check it out. Also, she's got fun intermediate goals: at $225 she'll be doing a podcast with Daniel Harper, and at $250 another with Jack Graham about Alien and The Shining. So please, help my daughter afford an apartment via her Patreon.

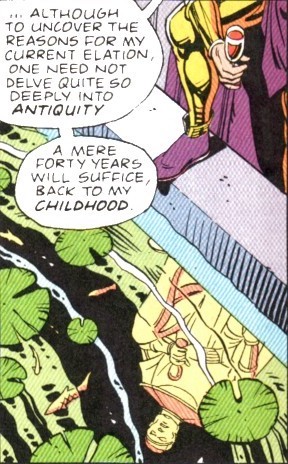

And so at last the story returns to where it began. Grant Morrison has, of course, been ever-present. As already discussed at length, his first professional credit predated Moore by five months. But he has been a shadow presence in the narrative, lurking at the edges, occasionally contriving to intersect it, waiting for his moment to take the stage in earnest. And now at last he arrives having always been here, and it becomes necessary to trace the story backwards, figuring out who he has been all this time.

This is, of course, a strange moment in which to observe Morrison, as he remains resolutely unspectacular. The work through which he will define himself is still ahead, the earliest plausible instances of it not emerging until two months after Watchmen finishes, his American debut still almost a full year away. At this point his greatest accomplishment is Zoids, where he surely acquitted himself well, but where he no more established himself as an impending major talent than Alan Moore established himself as the man about to revolutionize comics with Skizz or Captain Britain. His career at this point has no V for Vendetta or Marvelman, nor even a Ballad of Halo Jones. To read the future out of this moment is to work in implication, finding patterns in the negative space. Getting it right is more about knowing the answer ahead of time than insight.

As a result, it is easy to overreach—to confuse historical event and inevitability. On a very basic level, whatever larger conclusions and patterns are inferred, the answer to how Grant Morrison achieved what he did and how he took up his role in the War is simple: he put a lot of work into writing comics that changed the world. This work did not exist in a vacuum; plenty of extremely talented people have worked just has hard to have an insignificant fraction of the insight. Nevertheless, to treat Morrison’s career as some historically deterministic phenomenon that extended out of Alan Moore’s actions would be an egregious error.

As a result, it is easy to overreach—to confuse historical event and inevitability. On a very basic level, whatever larger conclusions and patterns are inferred, the answer to how Grant Morrison achieved what he did and how he took up his role in the War is simple: he put a lot of work into writing comics that changed the world. This work did not exist in a vacuum; plenty of extremely talented people have worked just has hard to have an insignificant fraction of the insight. Nevertheless, to treat Morrison’s career as some historically deterministic phenomenon that extended out of Alan Moore’s actions would be an egregious error.

So too would it be to suggest, as Morrison repeatedly does, that his career could have happened without Moore. Did Morrison come to writing comics on his own? Yes. Did he have his own interests and influences that, while certainly overlapping with Moore, were nevertheless his, interpreted and responded in ways utterly and necessarily unique to him? Yes. But none of that changes the fact that the career Grant Morrison had existed in a large part because Alan Moore did it first. The wave of Karen Berger edited books that started with Animal Man happened because Alan Moore did Swamp Thing. The genre of literate, politically invested superhero comics for adults that Morrison made his name in originated with Marvelman and V for Vendetta. Morrison admits as much, both in 1985 when he acknowledges that “only the advent of Warrior convinced me that writing comics was a worthwhile occupation for a young man” and much later in Supergods when he describes how he and the rest of his generation hit the American superhero scene in the wake of Moore: “And so we arrived in our teens and twenties, in our leather jackets and Chelsea boots, with our crepesoled brothel creepers and skinhead Ben Shermans, metal tattoos, and infected piercings. We brought to bear on the ongoing American superhero discourse the invigorating influence of alternative lifestyles, punk rock, fringe theater, and tight black jeans. We rolled up in anarchist hordes, in rowdy busloads, drinking the bars dry, munching our hosts’ buttocks (artist Glenn Fabry drunkenly assaulted editor Karen Berger’s glutes with his molars), and swearing in a dozen or more baffling regional accents. The Americans expected us to be brilliant punks and, eager to please our masters, we sensitive, artistic boys did our best to live up to our hype.”

The truth is that it was never Moore’s work that Morrison was imitating, but his career. There are similarities in their works, yes, but the truth is that there are even more similarities between Moore’s work and that of Neil Gaiman, whose early DC comics are much more faithful in their imitations of Swamp Thing than Morrison’s. So why is Gaiman the acknowledged protege and Morrison the despised rival? Again, one answer to this question extends out of specific decisions and choices—specific actions Morrison took in crafting his public persona that alienated Moore, and specific decisions both men made in the face of that antipathy. Another answer, however, is more esoteric, extending less out of decisions anybody made than out of the fundamental cultural relationships in play—a necessary consequence of the particular streams of influence and iconography that both men brought to the precise historical moment they did.

Figure 1140: Grant Morrison's illustration for his article on sword and sorcery comics. (From White Tree #2, 1977)

In this regard, contributing factors. First of all, Morrison was always more straightforwardly rooted in superheroes and genre fiction than Moore. He writes of this love with vivid and tangible passion throughout Supergods, making it clear that superheroes were not merely a genre he enjoyed, but something deep and central to who he was in a way that none of Moore’s comments on childhood love of the genre ever suggested. For Morrison, superheroes were an object of almost religious importance, the “Faster, Stronger, Better Idea” that could fight “the Idea of the Bomb that ravaged my dreams.” As he puts it bluntly in Talking With Gods, during a period in which he didn’t go out or do anything, “I really felt like they’d saved my life in a way.” Even his wider interests tended to circle back to this—a 1977 article for the fantasy fanzine White Tree, to which Morrison also contributed the an ongoing serial entitled Armageddon and Red Wine, tackled the genre of sword and sorcery literature through the lens of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian comics. And indeed, the fact that his 1970s zine work was on fantasy in the general case, in contrast with, say, Alan Moore, who was bouncing around the Northampton Arts Lab dabbling in a broader spectrum of avant garde and performance art.

Even when Morrison, in his account, fell out of love with superhero comics for a couple of years following his disappointment at the 1978 Superman vs. Muhammad Ali (a period, notably, that overlapped precisely with Captain Clyde), his interests stayed broadly in the sci-fi/fantasy niche. Where Moore had roots in the avant garde and the underground comix scene as well, Morrison had more of a singular tap root into the sci-fi/fantasy genre in general, and superheroes in particular. This is not to suggest that Morrison’s roots were comparatively impoverished, although Moore would surely draw that conclusion, nor that Moore’s roots did not also contain deep affection for and knowledge of superheroes. Simply that at the end of the day, Morrison had a loyalty to the specific genre of superhero comics that Moore did not.

A second factor: Morrison was, from the start of his career, also overtly working with magic. This commenced somewhere around the beginning of 1979 when Morrison’s uncle gave him Frieda Harris and Aleister Crowley’s Tarot deck along with a copy of Crowley’s The Book of Thoth. Intrigued, he sent away for The Lamp of Thoth, a British occult magazine of the 80s. He was quickly drawn to the then emerging chaos magic scene, which had largely been kickstarted by the publication of Peter Carroll’s Liber Null the year before. Describing his first ritual, he recounts performing an “invitation to magic,” asking it to let him in. “I got the candles out, I did the magic words, I did the circle, I did the banishing and all that stuff,” he explains. Laying down after, “there was a kind of gravitational point in the air int he room which was drawing all the perspectives towards it as if there was a hole there or a crack. And there was the sense of black oil filling up the folds between the brain.” Scared, he appealed to Jesus, at which point an angelic lion’s head manifested, proclaiming “I am neither north nor south.”

Figure 1141: Grant Morrison's familiarity with magic was evident as early as Gideon Stargrave. (Written and drawn by Grant Morrison, from "The Vatican Conspiracy" in Near Myths #4, 1979)

Lest one believe that this is post facto justification contrived as part of his rivalry with Alan Moore—an accusation Moore leveled in his incendiary “last” interview, where he claims that “several months after I’d announced my own entry into occultism and the visionary episode which I believed Steve Moore and myself to have experienced in January, 1994, Grant Morrison apparently had his own mystical vision and decided that he too would become a magician”—Morrison’s early career work entirely supports his account of things. The Vatican Conspiracy contains a panel in which someone conducts a ritual to consecrate a circle taken from Reginald Scot’s 1584 The Discoverie of Witchcraft, conducted in what is recognizably a Circle of Solomon as described in The Lesser Key of Solomomn. And his 1983 zine Bombs Away Batman contains a page of book recommendations including the Illuminatus! Trilogy, Michael Talbot’s Mysticism and the New Physics, and Aleister Crowley’s Magick. (“Learn to manipulate reality with Old Uncle Aleister. If you’re sceptical it’s your duty to try it out for yourself.”) It’s not even possible to argue that Moore was instrumental in Morrison’s decision to be open about his occult interests: he talks about it in multiple interviews going as far back as 1988, where he talked to Arkensword about his “forays into the occult, specifically into Chaos Magick, the current that's revolutionised the occult world during the last 6 or 7 years.”

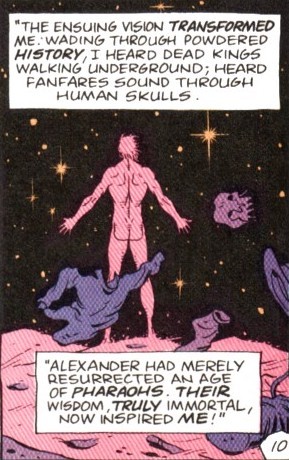

And so all of Morrison’s actions, from his juvenilia through to his calculated and efficient post-Moore assault on the now crumbling gates of the mainstream comics industry, It is true that Morrison’s conception of magic differs from Moore’s; he’s less focused on art as the specific vehicle for magic and more focused on the traditional notion of directly affecting reality—Morrison and his friend Gordon Goudie both recall Morrison magically locating Goudie’s missing guitar in the early 80s. That is not to say that Morrison’s art is not at times overtly magical—he’s been unambiguous about viewing The Invisibles that way—but it means that he does not necessarily view every Zoids script and every Future Shock as a magical spell in the same way that Moore would eventually come to. Nevertheless, he was magically aware, and was viewing the world in a magical way for more than a decade before Moore did.

Figure 1142: Polly Styrene of X-Ry Spex converting Grant Morrison to punkhood on Top of the Pops.

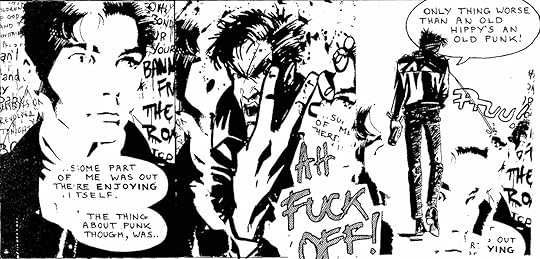

Third: he was a punk. Morrison has told the story of becoming a punk in multiple ways; in a 1988 one-pager called “Born Again Punk” for Heartbreak Hotel he said that “1977 was almost a religious thing—a conversion I suppose,” but in Supergods he dates it to 1978, saying that he’d initially dismissed punk “as some kind of Nazi thing after seeing a photograph of Sid Vicious sporting a swastika armband,” only coming around when seeing X-Ray Spex perform “The Day The World Turned Day-Glo” on Top of the Pops in 1978. In either account, however, the vigor of his newfound passion is clear. Writing in Supergods, he explains that “the world started to make sense for the first time since Mosspark Primary. New and glorious constellations aligned in my inner firmament. I felt born again.”

Figure 1143: Grant Morrison being punk. (Written and drawn by Grant Morrison, from "Born Again Punk" in Heartbreak Hotel #4, 1988)

Morrison was, however, a curious sort of punk. As he admits in “Born Again Punk,” he did not actually dress the part, wryly joking, “I know people who claim to have seen me with spiky hair, a leather jacket and drainies in 1978… maybe while I sat in my bedroom, listening to Peel and ‘Streetsounds’.” And this is backed up—a common refrain of anybody telling early 80s Grant Morrison stories is the extent to which he was a shy and awkward sort of geek. This is not, of course, incompatible with being a punk, but it reflects a sort of aspirational relationship with the brash disruptiveness of punk—one captured in Supergods when he describes how “this, for me, was the real punk, the genuine anticool, and I felt empowered. The losers, the rejected, and the formerly voiceless were being offered an opportunity to show what they could do to enliven a stagnant culture. History was on our side, and I had nothing to lise. I was eighteen and still hadn’t kissed a girl, but perhaps I had potential. I knew I had a lot to say, and punk threw me the lifeline of a creed and a vocabulary—a soundtrack to my mission as a comic artist, a rough validation.”

These factors in mind, turn to how he got to this point. His upbringing as the child of an antinuclear activist has come up before, but it’s worth pausing to look more at his father, who was an extraordinary figure in his own right. Walter Morrison volunteered for the army in World War II out of a hatred of fascism, but quickly came to find that, as he put it, “So I go into the military thinking we’ve got a crusading crowd of people here, who are even more aware than the civilian – that he’s prepared to get a gun and go and fight for that guy. And then to find in that situation that this guy knows less about freedom than what I’d come from, and what I’d been taught. And that everything I had been taught about the baddie, the Nazi and the fascists was plonk there in front of me, in this crowd of people who were supposed to be enlightened, informed and geared up to fight it. So how the hell do you move from that square to the enemy? When you find the enemy’s in your midst?”

These factors in mind, turn to how he got to this point. His upbringing as the child of an antinuclear activist has come up before, but it’s worth pausing to look more at his father, who was an extraordinary figure in his own right. Walter Morrison volunteered for the army in World War II out of a hatred of fascism, but quickly came to find that, as he put it, “So I go into the military thinking we’ve got a crusading crowd of people here, who are even more aware than the civilian – that he’s prepared to get a gun and go and fight for that guy. And then to find in that situation that this guy knows less about freedom than what I’d come from, and what I’d been taught. And that everything I had been taught about the baddie, the Nazi and the fascists was plonk there in front of me, in this crowd of people who were supposed to be enlightened, informed and geared up to fight it. So how the hell do you move from that square to the enemy? When you find the enemy’s in your midst?”

As one might expect from this, Walter Morrison had a difficult time in the army. In one of his most entertaining anecdotes, King George VI came to inspect his unit, and asked him how he liked the Army. As he tells it, “Without much hesitation I told him I didnae like it.” In another instance, after being sent to India, he was informed that his unit would be facing women and child protesters, and given the order to shoot the protesters if they advanced; his response was that he would be the first to open fire, first shooting any soldier that turned his gun on a woman or child and then shooting the officer who gave the order. The result was one of his several stints in the Glasshouse.

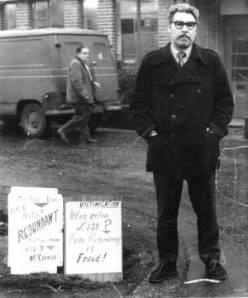

Figure 1144: Walter Morrison protesting.

After the war, Morrison retired to a life of activism. The bomb was his most frequent target, but he was an unrepentant radical, pacifist, and anarcho-socialist. On one instance, after his friend Stuart Christie was arrested in Spain for trying to assassinate Franco, Morrison went to picket the Spanish embassy, where he was promptly arrested and subjected to a lengthy interrogation over his political affiliations. (Christie also largely corroborates Grant Morrison’s story of his father being threatened by men in black, although Christie sets the incident at a protest near the pier at which the nuclear submarines were serviced as opposed to a nighttime visit to the home.)

The influence Morrison’s father upon him is clear enough in his sense of radicalism and the iconoclastic. But their relationship was complicated; it was through his father’s activism that Morrison’s deep fear of the bomb arose, after all. And when he describes his parents’ divorce in Supergods the sense of blame is clear: “Dad’s marital betrayals were more than Mum could handle. Like the cvracked vases that she chucked in the bin for any sign of imperfection, Dad was irreparably fractured. He’d always dug the broken pieces out of the trash and painstakingly Scotch-taped them back together, but in his case the damage was irreversible.”

Figure 1145: Barry Kitson's illustrations for "Osgood Peabody's Big Green Dream Machine" (From Superman Annual 1986, 1985)

In decades to come, Morrison would mine his sense of confusion and pain over the divorce for his Batman run. All of this, however, lay far in the future; in his early career, his only opportunity on the character came in the UK 1986 Batman Annual, in which he published a three-page illustrated prose story alongside one in the equivalent Superman Annual. In this he was once again following in the footsteps of Moore, who’d published a similar diptych the previous year. These pieces are, to be sure, mediocre—particularly the Batman one, entitled “The Stalking,” which is a bland piece about Catwoman breaking into the Batcave marred by a clumsiness of prose. The Superman piece, “Osgood Peabody’s Big Green Dream Machine,” is better, with a sense of endearing absurdity—at one point Peabody, who has invented a machine that can see into people’s dreams and proposes to use it to find Superman’s weakness, is asked whether he sleeps in his labcoat, and offendedly insists that of course he does, and the story ends with the reveal that everyone has actually been looking at Krypto’s dreams, and that the frequent images of bones were not, in fact, symbols of Superman’s underlying fear of death. It’s witty, but clearly juvenile—the work of a writer at the beginning of his career. (Moore, meanwhile, published "For The Man Who Has Everything" the same month.)

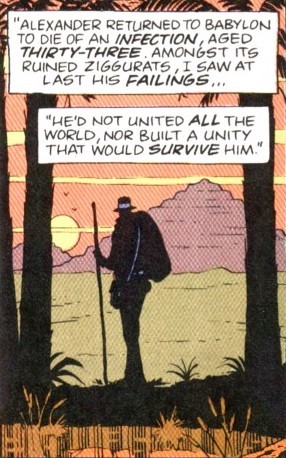

That this would still be true in 1985 when Morrison’s career had begun in 1978 is striking. By 1985 Moore was a titan. Not yet thirty-three, he’d hit it big at DC after revolutionizing the British comics industry, and was preparing to write the work that would end the Cold War. Morrison, meanwhile, had not meaningfully advanced from the upstart teenager who’d landed a comic in Near Myths seven years previous. That magazine had folded, he’d been sacked from the Govan Press, and his comics career consisted of a few Starblazer comics knocked off for spare cash. His career floundered, looking like it would be over in a flash, unnoticed by essentially everyone. And then, in 1985, he returned to the industry to try again. What had happened in the meantime?

That this would still be true in 1985 when Morrison’s career had begun in 1978 is striking. By 1985 Moore was a titan. Not yet thirty-three, he’d hit it big at DC after revolutionizing the British comics industry, and was preparing to write the work that would end the Cold War. Morrison, meanwhile, had not meaningfully advanced from the upstart teenager who’d landed a comic in Near Myths seven years previous. That magazine had folded, he’d been sacked from the Govan Press, and his comics career consisted of a few Starblazer comics knocked off for spare cash. His career floundered, looking like it would be over in a flash, unnoticed by essentially everyone. And then, in 1985, he returned to the industry to try again. What had happened in the meantime?

Figure 1146: Band photo of Grant Morrison and the mixers.

For the most part, Morrison tried to become a rock star. The main vehicle for this was the Mixers, a band spearheaded by Dannie Vallely and Ulric Kennedy in which Morrison played rhythm guitar. The band, named for a throwoaway line in A Clockwork Orange, split the difference between Morrison’s newfound punk interests and the 60s mod aesthetic Morrison was otherwise drawn to—“the Hollies on speed,” as one review apparently described them. Morrison’s account of the band is modest—as he puts it, “We weren’t great musicians, but we had a lot of enthusiasm. The trouble is, everyone was coming from a similar place of damage. We weren’t very good at being a band… we were a kind of crappy band, but we looked beautiful and we sounded really great.”

Given that virtually all that survives of the band are CD-Rs of their 1984 album Speed, Madness, Flying Saucers, which was in turn copied from a cassette tape, Morrison’s boast of quality is difficult to evaluate. Comparing the Mixers straightforwardly to contemporaneous bands like the Smiths or Echo and the Bunnymen runs aground against the fact that those bands had professional studio recordings The Smiths eponymous first album cost six thousand pounds and involved ditching the entire first studio session and starting over; even the handful of Mixers tracks to emerge on CD-released compilations are clearly hastily produced efforts by a bunch of kids on the dole.

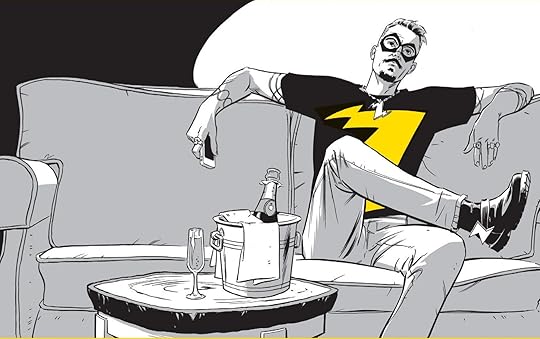

Figure 1147: Grant Morrison in full dandy attire.

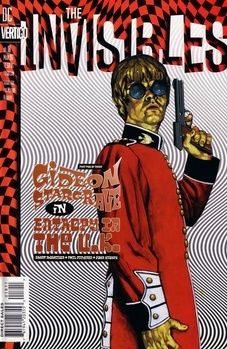

Nevertheless, even the most charitable reading of the Mixers would conclude that they were simply the wrong band for the time. Morrison cultivated a flamboyantly retro mod aesthetic, dressing much like Gideon Stargrave eventually would in The Invisibles—his first real effort at the ostentatious public personality he sought—but in doing so he just missed the New Romantic scene. Similarly, the band’s 60s retro sound might have fit well in glam, which was fundamentally a classic rock revivalism with more flamboyance, but again, was far too late to catch this wave. Instead, as pop music made the swing towards the postpunk influenced second British invasion, the Mixers attempted to jump ahead straight to Britpop and fell into the decade-wide chasm between them, never to be seen again.

Figure 1148: Gideon Stargrave dressed in an outfit directly lifted from Morrison's own past. (Art by Sean Phillips)

But while the Mixers may not have been successful musically, they provided an important stepping stone between the nineteen year-old Morrison—a shy geek drawing comics—and the persona he would eventually craft for himself. As mentioned, his Mixers-era persona was a flamboyant mod—outlandish and brightly colored jackets—Frank Quitely describes it as “dandyish in a kind of very skinny Oscar Wilde kind of way.” As he put it, “I formed a band, and just started to live, and get out, and dress up and be the person I’d always wanted to be.” He’d hang around Glasgow, a “mod shaman” going to pubs like the Rock Garden and reading Tarot for anyone seeking advice.

The band as a whole cultivated a similarly brash attitude. In Bombs Away Batman, Morrison cheekily presents an interview with the band in which they affect a posture of brash arrogance. At one point, Morrison proclaims “the charts are full of dross. I don’t believe there are more than a handful of bands on the whole planet who really care about what’s going on and want to change it. And the so-called ‘subversive’ bands like Crass wouldn’t know subversion if they fell over it, that’s why they never achieve anything.” But the ambition for overall fame was clear—at one point, discussing their hatred of how the musical landscape had fragmented into endless subcultures, Ulric Kennedy proclaims that “we just want there to be a mainstream so everyone likes us.” Within the braggadocio, however, Morrison repeatedly outs himself as someone with more intellectual goals—at one point he muses about how “in all the magazines it’s ‘fun fassions of the ‘50s’ and all the crap. And everyone’s falling for it. It shows you how easy it is to rope the kids in on a general shift towards a puritanical right wing value system—Thatcher and Reagan trying to create the old world again.” Or, at one point, the genuinely amazing exchange in which Morrison and the interviewer, who is, recall, Morrison proceed to finish each other’s sentences in the course of a lengthy reverie on Von Neumann, quantum physics, and the UK music press.

The band as a whole cultivated a similarly brash attitude. In Bombs Away Batman, Morrison cheekily presents an interview with the band in which they affect a posture of brash arrogance. At one point, Morrison proclaims “the charts are full of dross. I don’t believe there are more than a handful of bands on the whole planet who really care about what’s going on and want to change it. And the so-called ‘subversive’ bands like Crass wouldn’t know subversion if they fell over it, that’s why they never achieve anything.” But the ambition for overall fame was clear—at one point, discussing their hatred of how the musical landscape had fragmented into endless subcultures, Ulric Kennedy proclaims that “we just want there to be a mainstream so everyone likes us.” Within the braggadocio, however, Morrison repeatedly outs himself as someone with more intellectual goals—at one point he muses about how “in all the magazines it’s ‘fun fassions of the ‘50s’ and all the crap. And everyone’s falling for it. It shows you how easy it is to rope the kids in on a general shift towards a puritanical right wing value system—Thatcher and Reagan trying to create the old world again.” Or, at one point, the genuinely amazing exchange in which Morrison and the interviewer, who is, recall, Morrison proceed to finish each other’s sentences in the course of a lengthy reverie on Von Neumann, quantum physics, and the UK music press.

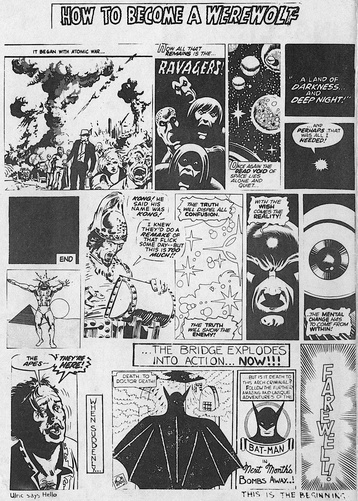

Figure 1149: Cut-Up Comics (Arranged by Grant Morrison, from Bombs Away Batman, 1983)

The ambitious arrogance of this interview is of a piece with Bombs Away Batman, which is probably the best single encapsulation of Morrison’s early 80s obsessions. In addition to a punk collage aesthetic, Morrison finds time to offer book recommendations (in addition to those already mentioned, A Clockwork Orange, High Windows by Philip Larkin, Red Shift by Alan Garner [who he interviewed for an issue of White Tree a half-decade earlier], The Stand, Richmal Crompton’s Wlliam books, Charles Berlitz’s Doomsday 1999, and, inevitably, the Jerry Cornelius books), a page on comics that consists purely of praise for Alan Moore (who “has singlehandedly lifted comics into a realm only partly glimpsed by previous writers,” although even here Morrison can’t resist complaining that he’s unimpressed with the “Warpsmiths” strip), a page of poetry that ends with the encouragement to send in “more of these great poems, especially one about God, the army, and nuclear war. If you can’t write them yourselves try looking through old school magazines or poetry fanzines and copy the best ones—participate!”, and a cutup comic entitled “How to Become a Werewolf.” It’s everything one wants from a young Grant Morrison—a burst of snarky, presumptuous, and intellectualized DIY punk.

The only thing it isn’t, unfortunately, is very much like the Mixers, whose retro songs about the trials and tribulations of love feel nothing like the iconoclastic “I’ll fight the whole damn world” zeal of their rhythm guitarist’s fanzine. And so it is perhaps unsurprising that the band steadily sputtered to a halt. As Morrison tells it, they were “spinning in multicolored circles, devolving to nothing more than posters, threats, and endless vague rehearsals.” Until eventually they’d stopped. Various combinations would try a few side projects over the next few years—the Favues, Ochre 5, and Jenny & The Cat Club, all with basically the same sound, but none left any mark, and by 1985 Morrison’s music career was dead and buried.

The only thing it isn’t, unfortunately, is very much like the Mixers, whose retro songs about the trials and tribulations of love feel nothing like the iconoclastic “I’ll fight the whole damn world” zeal of their rhythm guitarist’s fanzine. And so it is perhaps unsurprising that the band steadily sputtered to a halt. As Morrison tells it, they were “spinning in multicolored circles, devolving to nothing more than posters, threats, and endless vague rehearsals.” Until eventually they’d stopped. Various combinations would try a few side projects over the next few years—the Favues, Ochre 5, and Jenny & The Cat Club, all with basically the same sound, but none left any mark, and by 1985 Morrison’s music career was dead and buried.

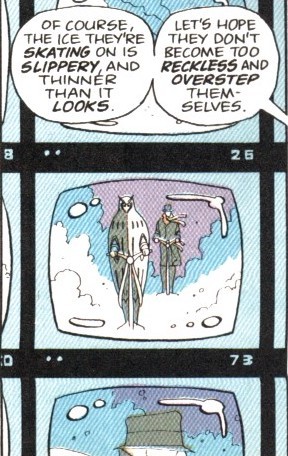

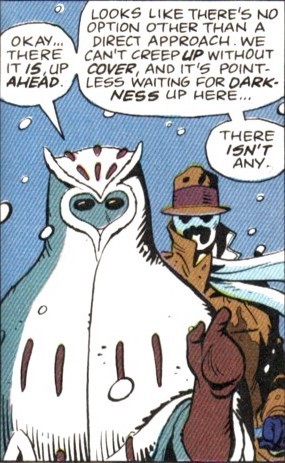

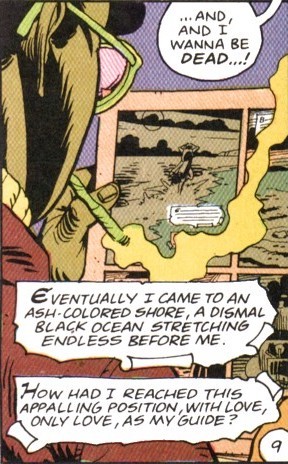

And so Morrison retreated back to comics. This was a slow process, to be sure. He started with “The Liberators” in Warrior, where he had the misfortune of arriving precisely as the magazine folded in February of 1985. A few months later he landed “The Stalking” and “Osgood Peabody’s Big Green Dream Machine,” and at the start of 1986 landed another text piece in Captain Britain and his first Future Shock in 2000 AD. Along the way, he also tried to reactivate various older projects—Gideon Stargrave made a two-page reappearance in the Food for Thought anthology, which also featured the Alan Moore/Bryan Talbot collaboration “Cold Snap” and an extremely early work of Warren Ellis’s from long before he was famous enough to get away with sexually abusing dozens of women. And, of course, he did the series of Zoids strips for Marvel UK, his first work to really catch eyes and turn heads.

Success breeds success, and Morrison soon found other work at Marvel UK. In June of 1987, the same month that Watchmen and Moore’s Swamp Thing run wrapped, Morrison penned a short five-page piece entitled “Meditations in Red” for Action Force Weekly. This mostly served as an introduction to Marvel’s Shang-Chi to set up a run of Master of Kung Fu reprints that would begin the next week, and is basically an infodump with no narrative ideas of Morrison’s own. But what this lacks in cleverness it makes up for in a sort of professional efficiency. Morrison is given a resolutely unglamorous job to do, and he does it. It’s not a job that can be done spectacularly—this is leading into reprints, after all, not some brand new Morrison-penned take on Shang-Chi where he can dramatically recontextualize his origin. But he does it well, clearly, and with at least a few moments of wit.

[image error]

Figure 1170: Steve Yeowell draws Zenith in middle age for "Permission To Land" (In 2000 AD Prog 2050, 2017)

Continuing their assertion of ownership over the character, in 2017, as part of their “Jumping On” issue Prog 2050 running all-new storylines, 2000 AD ran a one-page text story entitled “Permission to Land” by editor Matt Smith, with a single piece of new art from Steve Yeowell illustrating a present-day Zenith. Framed as an in-universe interview with the now fifty year old pop star. He’s promoting a new album, called Chimera, Peter St. John is apparently deceased and with a posthumous memoir that reveals some of Zenith’s role in things, but for the most part there’s not much to it—an empty throwaway of a piece that suggests the concept is better left in the past, and, indeed, with its actual writer, than dragged out thirty years on for an anniversary piece.

But this somewhat pathetic afterlife of Zenith does little to diminish its stature within its historical moment, or even how well most of the original four Phases hold up. As a first major work for Grant Morrison, they show the creator he would be: endlessly innovative, unrepentantly brash, and utterly unintimidated. Does his response to Watchmen equal the original? Of course not. No responses to Watchmen equal it; it’s Watchmen, after all. But what Morrison did accomplish—taking to the pages of one of the magazines Moore had come up via and writing a post-Watchmen comic that offered a fundamentally new take on the genre—is staggering in its magnitude. In one stroke, Morrison declared himself a major talent. Now all that remained was for him to make his move on the US market.}

The Last War in Albion Volume 2 will conclude on August 3rd.

Philip Sandifer's Blog

- Philip Sandifer's profile

- 48 followers