Philip Sandifer's Blog, page 53

April 14, 2017

Shabcast 31 (Chatting 'Species' with Josh)

Happy April 14th to you all. The Shabcast is back once again (slightly more structured and sobre than last time), featuring the return of one of my favourite semi-regular guests, our very own Josh. This episode is a tie-in with his last essay, and features the two of us chatting about Species (1995), perhaps the very definition of a movie that is really interesting despite being pretty bad. Josh's redemptive reading is fascinating, and we also ponder such imponderables as why people like Ben Kingsley and Forest Whitaker agreed to be in it, why cars explode when they crash in movies, and why this film goes out of its way to feature a scene where Natasha Henstridge stares bemusedly at a stuffed fox. Plus there are the usual digressions. H. R. Giger, dinosaurs, Captain Kirk, Avital Ronell, etc.

Happy April 14th to you all. The Shabcast is back once again (slightly more structured and sobre than last time), featuring the return of one of my favourite semi-regular guests, our very own Josh. This episode is a tie-in with his last essay, and features the two of us chatting about Species (1995), perhaps the very definition of a movie that is really interesting despite being pretty bad. Josh's redemptive reading is fascinating, and we also ponder such imponderables as why people like Ben Kingsley and Forest Whitaker agreed to be in it, why cars explode when they crash in movies, and why this film goes out of its way to feature a scene where Natasha Henstridge stares bemusedly at a stuffed fox. Plus there are the usual digressions. H. R. Giger, dinosaurs, Captain Kirk, Avital Ronell, etc.

Download the episode here. Beware spoilers and triggers.

Also, here are some links to things we mention:

Here is the Vimeo video comparing Species to David Lynch's Mulholland Drive.

And here's the (excellent) article about how and why Kirk is misremembered, by Erin Horáková at Strange Horizons.

April 12, 2017

Sensor Scan: Species

[image error]1995 was a major turning point in my association with pop culture. It was the year my family first got satellite TV, and while this meant I finally had access to television besides three channels of varying degrees of snow for the first time ever, it also meant the end of my association with Star Trek for five years.

I've of course told this story a lot, but it bears repeating one more time. In the 80s and early 90s, Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine had an unusual direct-to-syndication deal, whereby they would be included as first-run series as part of a syndication package local affiliates of the major national networks could bid on to fill gaps in their programming schedule, which would otherwise include stuff like game shows or reruns of popular series from past decades. For those outside of the US, in this country our national networks have local regional partners for every municipal area, and while they all get the network's primetime shows, stuff like local news and weather will be different station to station. Back in those days the syndicated shows were different too, which could lead to weird things, like, say Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine competing with each other (and sometimes even reruns of each other) because two different local affiliates for two different networks decided to air them both in the same timeslot. It...wasn't always the best system, let's say.

But even though I only had three channels, it never bothered me. I've never been a huge TV person (partly because of this), so I didn't care. I had PBS, cartoon shows and Star Trek. What more could I possibly want? But all that changed in 1995 with our shiny new satellite dish. And while it was certainly exciting to have so many new channels to explore, it came with a serious price. In the mid-90s, the satellite provider my family used didn't offer local channels, instead providing a generic national version of PBS and the networks with no regional content whatsoever. This included syndication, so that was the abrupt end of my association with Star Trek on television, I thought forever (while Star Trek Voyager was sold as an exclusive to UPN, Paramount's ill-advised attempt to make a network to compete with ABC, NBC, CBS and FOX, UPN wasn't included in our satellite package either until Voyager had ended. In fact, we didn't get UPN until midway through Enterprise's first season).

This also means that 1995 is where I drop out of Vaka Rangi's narrative, effectively for good. I'll pop by to check in on Star Trek every so often over the next half-decade (usually with a somewhat baffled and concerned expression on my face) and it will always be something I default to saying I broadly like, but my fever for adventure At the Edge of the Final Frontier will be nowhere near this intense again. My passion will briefly return to flashpoint levels once TNN picks up Star Trek: The Next Generation reruns in 2000 and the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine DVD box sets are announced three years later, but I've already talked a lot about that in the Next Generation section. I'll also have an Indian Summer romance period of sorts with Enterprise's first few seasons, and then the 2009 movie will kickstart a period of nostalgic self-reflection and contemplation that will eventually lead me, well, to Vaka Rangi and Eruditorum Press. But here in 1995, that all may as well be a lifetime away. From this point on, my interests will take me elsewhere.

But I won't leave without sharing one last examined memory with you. I want to show you where I went after Star Trek.

Upon getting my shiny new satellite dish, the places I gravitated to first were Cartoon Network, Nickelodeon and The Discovery Channel. Cartoon Network helped foster my love of animation and animation history (a project unto itself), and Nickelodeon was fun because I got to see what youth culture out in the real world was like (this was back before Nickelodeon made cartoons) but The Discovery Channel was great because it was the first time I had 'round-the-clock access to documentary nonfiction. I absolutely ate that up, and the kinds of shows I watched there are still the shows I prefer to watch if given the opportunity today (also, we were speaking earlier about Multimedia CD-ROMs and I can't tell you how many Discovery Channel-branded interactive CD-ROM suites I had. None of them worked properly, of course). Though I liked the history and archaeology programmes (remember, I had long been a fan of Robert Ballard's oceanography work), my absolute favourites were the nature documentaries. Perhaps it's because of where I grew up, but the natural world has always been one of my oldest loves and it's something I try to be mindful of every day. The quiet, informative and relaxing tone of those old documentaries were really compelling to me not just as educational tools, but as media sensory experiences.

But alongside all these new documentaries and cartoons I was watching, I also naturally saw a lot of commercials. There were commercials of all sorts, of course, but some of the earliest ones I remember seeing in crystal clarity on my 80s CRT thanks to my satellite service were for movies coming out in the summer of 1995. And they were certainly a weird bunch: There was Outbreak, a movie about the CDC fighting a pandemic that I think involved brushfires and was an action movie for some reason, the third Die Hard movie (I hadn't seen either of the first two), Unzipped, an...unexpected documentary about supermodels and the fashion industry, Congo, a movie based on one of Michael Crichton's earliest works that, in hindsight, was made probably just to compete with Steven Spielberg's 1993 Jurassic Park movie (which I had seen, or was at least well aware of thanks to my interest in paleontology) Judge Dredd (which Eruditorum Press readers most assuredly know more about than I do) and Batman Forever (I've already written about my history with the two Tim Burton Batman movies, and you can say what you will about the two Joel Schumacher ones, but I'll tell you what: The trailer for this one at least was a trip and a half at the time). And then there was Species.

Of all the movies that came out that summer, only one truly managed to capture my imagination, and that was Species. I recognised Batman, of course, and I was interested in Congo because it was about an African rainforest and gorillas and had a female lead and that seemed cool, but Species was what I was really interested in and Species was what I wanted more than anything: That film absolutely lodged itself in my psyche from the trailer alone and it's never really left. Perhaps you're familiar with Species and its...reputation, and, if so, I'll let you decide for yourselves what you think that says about me. But at the time I thought Species was simply mesmerizing: I could tell from the commercial it was science fiction, and since the only science fiction I really knew in 1995 was Star Trek and perhaps the odd video game, Species was unlike anything I'd ever seen before. The title and the trailer both evoked zoological and natural history themes, and, given what I was getting more into in 1995, that definitely caught my attention. And then of course, there was everything else about it.

I want to handle this as delicately as possible without implicating myself in any direction, but it's impossible to talk about Species without talking about sex and sexuality. And believe me, we'll get to the meat of that in due time. To start with, I'll just say I definitely noticed the sex (as profoundly unsexy as that first trailer is in a lot of ways: It tries to sell the movie as a 90s thriller on par with everything else that came out that summer, which it is. Sometimes.) and that was certainly part of the reason I was so interested in the movie, but not for the reasons you probably think I was. In spite of its reputation, most of what's sexy about Species is actually what it doesn't show and conveys only through implication: It leaves the bulk of that kind of stuff to your imagination, and I maintain the movie is generally speaking more nuanced and subtle then it gets credit for being. I suppose I intuited the sexual themes in Species the same way I did Jadzia Dax's sexuality in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and was subconsciously drawn to it that way.

Species also had a truly formidable-looking female lead, and I'm not talking about Marg Helgenberger.

I can't remember if I saw Species that summer or not (I can't see how I would have): It *might* have been one of the rare movies we got second run at our little village cinema, back when we still had one, but I'm sure I would never have dared go see it even if we did. Even then I knew this was something I probably wasn't “supposed” to like as much as I was starting to think I probably did. Most of my understanding of Species at the time was derived from watching the trailer whenever it showed up during commercial breaks and making educated guesses about what kind of movie it was and what it was trying to say based on what little information I had. And that commercial really was the bulk of what I had: I wasn't getting science fiction magazines anymore at this point, and even though Species was the big tentpole sci-fi movie of 1995 and was heavily profiled in all of them, I never knew that until years later long after I got the Internet, mostly doing research for this project, in fact.

Either way, for better or for worse, this where my interest in science fiction led me for the next several years. With no new Star Trek to watch, it turned out to be Species that more or less defined how I viewed science fiction and my experience with the genre from 1995-2001. It kind of became a closet fandom of sorts for me. In fact, Species was so influential on my critical development that it shaped how I reread Star Trek after I went back to it. It's more a topic for the sequel (which I will not be covering) because it came out the same year, but remember that Star Trek Phase II book Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens wrote? You know, the one that had the complete original script for “The Child” included as an Appendix? Yeah, that came out the same year as Species II. I was *absolutely* comparing and contrasting those two, and they sort of...cross-pollinated each other in my mind. Over the years, I would occasionally catch glimpses of Species and its sequels on the Sci-Fi Channel where they would show up as weekend shlock features every so often, always with more than a slight twinge of embarrassment at having done so. But it wasn't until much later that I actually got to watch the movie all the way through from a critical perspective and fairly evaluate what it did and didn't do: I knew Species was going to have to be a major milestone for Vaka Rangi from the very beginning, and thankfully, it's really not bad. Wonky and full of plot holes, but not bad.

As some of you may know, Species is very intimately connected to the Alien series. Some would call it a spiritual successor to the original Alien, others would call it a shameless ripoff. Which of the two it is I'll leave you to decide for yourselves. I personally think it's a little bit of both. In fact, knowing I was absolutely going to have to cover Species once I hit 1995 is the reason why I even bothered to look at Alien and Aliens as part of Vaka Rangi in the first place, even before I remembered the Tasha Yar-Private Vasquez connection, because to really understand what this movie is doing (or trying to do), you need that context. If you'll recall, the big thing that was special about the original Alien (and significantly less so its sequels) is that it was a sexual horror movie: It takes Western culture's hangups about sex, as well as its patriarchal oppression, and throws all that back at it in the form of a lumbering penis monster. It *literally* shoves it back down its throat. Screenwriter Dan O'Bannon said his primary goal was “to make the men in the audience uncomfortable”: Alien is a movie that shows how monstrous rape culture is by turning rape culture into a monster.

And Species is a sexual horror movie too, just like Alien. In fact, I'd argue it's more one than any of the Alien sequels or franchise films and comes the closest of any of them to being a true follow up to what that first movie achieved. Species had a very painful and difficult birth, even by Hollywood standards, and some of this does blunt its effectiveness: It has a tendency to be laughably incoherent at points and it does basically go off the rails spectacularly in its final act, but when it's good it's really good and gets at some truly compelling ideas. The cornerstone of the whole film is Sil, played first by a young, pre-Dawson's Creek Michelle Williams, and then by Canadian model-turned-genre queen Natasha Henstridge, in her debut performance. Sil is the result of a covert government experiment to genetically engineer a new life-form out of human and alien DNA (no, not that kind, but you wouldn't be too far off in thinking so). Her handlers get cold feet though, and decide to “terminate the experiment” (read: gas her) at the start of the movie. Needless to say, Sil doesn't take that well and breaks out, going on the lam to survive and setting off a nationwide manhunt.

Half the movie thinks Sil is its leading lady. The other half thinks she's its Great Beast to Be Slain. I think she's the heroine.

Sil's alien form was designed in part by H.R. Giger, who was brought on to oversee some of the visual look of the film. It wasn't a fun experience for him, and he wrote at great length about how he felt creatively constrained by the whole process. But Giger, just by his mere presence here, can't help but invoke Alien (certainly the filmmakers wanted him to), even though he tried very hard to differentiate the two films. In particular, Giger wanted Sil to be a kind of defining statement for a side of his work that hadn't gotten mainstream respect yet at that point: Its feminine side. Sil was meant to be an “aesthetic warrior”, “beautiful, but also deadly”. Partly as a result of this, the twist Sil brings to the sexual horror formula is that while Alien depicted a certain type of sexuality as horrifying, Species depicts a certain, different kind of sexuality as horrifying diegetically and it wants us to think about the ramifications of that. Unlike the Alien, Sil doesn't stand in for rape culture, but what is, to my eyes, a perfectly innocent flavour of feminine sexuality. As the characters in the movie never tire of pointing out, Sil wants to mate and have a baby, an idea that she likes and feels nice to her. And that's it.

The script tries to paint this as a kind of invasive biological attack on humanity because Species originated as a pitch about an alien invasion through “wetware”, and the project on the whole has a somewhat bonkers grasp of natural selection and a somewhat worrying fixation on evolutionary psychology. But we never get any indication in the finished product that this is something Sil actually wants: She doesn't seem to want to hurt anyone (though the movie is inconsistent about this because it's inconsistent about everything) and generally just seems more interested in exploring herself and her desires in privacy and safety. Natasha Henstridge deserves a ton of credit here (as does Michelle Williams) for bending over backward to make Sil sympathetic, even when the script plainly doesn't want her to be, and it's really hard not to cheer for her when the actresses are left to their own devices. Thanks to Sil's powers of rapid growth and maturation, she grows to adulthood in days and picks up a lifetime of experience in hours: So here's a young woman coming of age into a world that hates and fears her who knows, as a hybrid who's neither fully one or the other, she's never going to fit in anywhere.

That alone could lead into some potentially really interesting discussions about diaspora and second-generation immigrants, but that's a discussion someone will have to have somewhere else. What I want to focus on, because I can't help but focus on it, is the sexual component. Because the real reason Sil is hated and turned into a monster is because she's a woman who has feminine desires. Her sexuality and sexual agency is feared and scorned and depicted as dangerous and threatening. There's a lot of ways you could interpret that from a feminist perspective and most them admittedly aren't terribly appealing, but I choose the redemptive tack that the movie is on our side...at least for enough of its runtime to leave the right impact. It *wants* us to notice that Sil is being hunted just because she's feminine and she's different and people don't understand her. It *wants* us to feel bad about that, and to feel for her innocence and her desire. At least, that's what I think Natasha Henstridge wants. Part of that comes from the fact that the rest of the cast is delightfully incompetent and unlikable (I mean hell, “Our Heroes” open the film by trying to gas a little girl to death because they were scared of her for no obvious reason), but most of it is, again, due to Sil herself.

That Species does, on one level, depict those selfsame feminine desires as monstrous can be read a number of different (negative) ways. This could be saying that all femininity or feminine agency is bad (which doesn't really gel because the back half of the movie really wants us to get behind Marg Helgenberger's Laura Baker and her romance with Michael Madsen's Preston Lennox wherein she is very much depicted as the proactive agent), or perhaps it's saying it's bad that 90s RIOT GRRL feminism has made women afraid to embrace certain desires. Or maybe it's a criticism of that very criticism. I personally don't think any of these hold though, because again, Sil is so sympathetic for so much of the movie. But also, consider the unique physiology she inherits from her...species: Perhaps because Sil matures at such a rapid rate and possesses incredible healing powers that allow her to come back from any injury, pregnancy, childbirth and development are casual things to her and can happen within the span of a few hours. And they're pleasurable to her. Isn't the movie then saying that women can enjoy being pregnant and having children without that defining everything about who and what they are? Isn't that a good thing?

Also, I personally always imagined this gave Sil an enhanced level of empathy and sensual maturity connected to her sexuality...Just like the Deltans and the Betazoids in Star Trek. This is the part of the movie that really does tie into the original theme of the human race potentially driven to extinction by introduced species: Sil isn't a monster, she's actually better than us, and that's what truly scares the human characters, even if they'd never admit it. Sil is pure, uninhibited feminine energy and creative power unbridled from Western patriarchy, and that positively terrifies Xavier Fitch and his crack team of US government stooges. Best to kill off that which you don't understand (and what has been more othered and less understood throughout human history than woman?) quickly so as not to bother yourself with a potentially serious challenge to your worldview and entitlement. Sil is life force and the combinatory energy of becoming in its purest and most supercharged form, and she is not in the least bit embarrassed, ashamed or intimidated by it. Whether or not this prospect terrifies *you* as well might determine how you understand what Species is saying.

Of course, Species then wants to have it both ways. It wants Sil to be this, but to also be a horrible monster we don't feel bad about seeing killed off in a spectacular and exciting fashion, leading to the movie's truly messed up and upsetting climax. This constant confused balking about its own thesis statement, probably due to its difficult production that likely passed through a few too many different hands a few too many times, is what ultimately undoes the film. It's a classic “too many cooks” problem, resulting in something I get the distinct impression was not quite what any one creative party involved with it wanted it to be. But even so this is still a movie I really enjoy and have a lot of tender feelings about. Whenever I rewatch it I surely laugh at the countless plot holes and janky exposition (I love how, by the way, Forest Whitaker's character Dan gives a shout-out to The Discovery Channel in one such scene) and the cast, all of whom (save Natasha Henstridge and Michelle Williams) are clearly taking the piss out of the whole hot mess. But I also can't help but see the the good in the film too: There's a germ of something truly brilliant and inspired here. No, more than a germ: It's in full bloom if you know where to look. I believe in Species and in Sil, more than I believe in a lot of things.

Back when I was getting into Species, I had no idea about the Alien connection. I'm not even sure I knew what the Alien series *was* in 1995. So what most people probably saw as an unrepentant and exploitative knockoff, I saw as something really intriguing and new. But more than anything else, it was Sil who fascinated and inspired me. Maybe it's because there weren't any real leading ladies in science fiction at the time who weren't part of an ensemble (at least none that I would have been aware of) that she stood out to me, though I'm guessing her sexuality was equally as important...Probably more so. I'd never seen anyone that forward or...open in pop culture before, at least not in a way that wasn't masked behind some kind of euphemistic metaphor (like Dax and Deanna). But I want to backpedal away from this a bit before I end up in a compromising position I can't recover from, and there is more about Sil I resonate with besides that.

Chief among them is her upbringing, or rather, her lack thereof. Sil may be brilliant (she has the savant-like ability to read an entire book just by glancing at the the pages, and can pick up difficult skills and concepts just by watching other people), but she's cripplingly ignorant when it comes to human culture and social interaction, especially in the West. This isn't her fault; she had a very sheltered and isolated childhood (she grew up in a literal cage after all), but it means that once she escapes into the real world her straightforwardness and honesty gets her into trouble and she starts from a handicap when it comes to social interaction. In fact, Sil spends a lot of time watching TV to try and get a better understanding of the world she finds herself in...which may or may not be to her benefit. As an only child living alone in the Actual Wilderness whose sole window into the outside (human) world was television and pop culture (and before 1995, and even after, secondhand pop culture at that) this really left a big and lasting impression on me. For this, and other reasons, I genuinely, honestly saw a lot of myself in Sil...and a lot of her in me.

Because I relate to her on so many different levels, I guess I kind of...refuse to accept some of the ways Species seems to want to characterize Sil. I feel compelled to defend her actions whenever and wherever possible, though that doesn't mean I blind myself to the actual intent of the text either (however that said piecing together what the actual “intent” of something like Species is proves to be unusually difficult, even for a movie, because so many people were pulling the project in so many different directions it's not altogether clear the *movie itself* knows what it wants to be). I'd never seen a character quite like Sil anywhere before, and I don't think I've seen one since either. I desperately want her to get a happy ending, because if she gets away, there may still be hope for me yet.

In my head, I have a version of this story I like and accept and is “canon” to me and that tends to override my more base critical tendencies. This is, I suppose much like Star Trek: Deep Space Nine - Hearts and Minds, a work I am altogether too close with to provide what I guess you'd call “proper critique. I think my reading of Species is a good and valid one, but I wouldn't force anyone else to subscribe to it if they don't want to or can't make themselves. This movie is something of a mess and I readily admit that, but it's stayed with me longer than most things for a reason. Species is kind of the definitive example of how I feel about the overwhelming majority of Vaka Rangi: If you don't share the exact unique and perverse positionality and circumstances that I do, a whole lot of this probably isn't going to make sense to you. All I can hope for is that I do a decent enough job *explaining* myself in a way you don't find totally repellent.

Why any of you are still reading, I may never understand, but thank you if you are.

April 10, 2017

The Proverbs of Hell 3/39: Potage

POTAGE: A thick soup, and a rather striking shift in the heartiness of courses that would probably destabilize a meal coming before egg and oyster courses. In this case, it flags the fact that this is an episode concerned entirely with the larger arc as opposed to with a killer-of-the-week.

POTAGE: A thick soup, and a rather striking shift in the heartiness of courses that would probably destabilize a meal coming before egg and oyster courses. In this case, it flags the fact that this is an episode concerned entirely with the larger arc as opposed to with a killer-of-the-week.

WILL GRAHAM: I like you as a buffer. I also like the way you rattle Jack. He respects you too much to yell at you no matter how much he wants to.

ALANA BLOOM: And I take advantage of that.

For all the problems with her character (see next note), Alana is quickly established as intelligent and competent. But even here there’s a certain drabness to her effectiveness, which stems at best from authorial fiat and at worst because he’s unwilling to yell at a woman. And given Jack’s relationships with other female characters, at worst is more likely. As for Alanna taking advantage, well, it’s tough to identify when she does this as opposed to either going along with Jack or protesting ineffectually.

ALANA BLOOM: Brought you some clothes. Thought a change would feel good. I guessed your size. Anything you don’t want keep the tags on. I’ll return it. And I brought you some music, too.

ABIGAIL: Your music?

ALANA BLOOM: If there isn’t anything you like, I got a stack of iTunes gift cards. I’ve got a stack of gift cards. I don’t do well redeeming gift cards.

ABIGAIL: Probably says something about you.

ALANA BLOOM: Probably does.

But what? To some extent this question has no answer. Alanna is after allthe show’s great cipher, a character whose purpose is first to prevent the show from being a complete sausage festival (quite the job), and second to be whatever else the show happens to need. This sort of characterization gestures broadly to the motiveless quirkiness of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, a role Caroline Dhavernas and Bryan Fuller had already explored and complicated more than a decade earlier in Wonderfalls. Hannibal, however, is not a place where pixies thrive, and these traits never quite add up to anything sensible.

ABIGAIL HOBBS: I don’t know how I’m going to feel about eating her after all this.

GARRET JACOB HOBBS: Eating her is honoring her. Otherwise it’s just murder.

The obvious reaction to this is the oft-giffed “cool motive, still murder” bit of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, but that’s manifestly not the ethical system Hannibal means to be working under. This is played as a desperate justification, a point emphasized by the original script, which had Elise Nichols’s body visibly mounted on the wall in this scene, thus moving the revelation that Abigail knew what her father was up to forward by several episodes. But the scene also plays Abigail and her father’s relationship as one with real tenderness, affection, and love. As before, the show is taking the idea that his cannibalism is a means of honoring his victims utterly seriously. Garret Jacob Hobbs isn’t wrong to insist that what he does isn’t “just murder.”

WILL GRAHAM: This copycat is an avid reader of Freddie Lounds and TattleCrime.com. He had intimate knowledge of Garret Jacob Hobbs’ murders. Motives, patterns. Enough to recreate them and arguably elevate them. To art. How intimately did he know Garret Jacob Hobbs? Did he appreciate him from afar, or did he engage him? Did he ingratiate himself into Hobbs’ life? Did Hobbs know his copycat as he knew him?

No, which is the closest Hannibal manages to come to consuming Hobbs. The real pleasure of this scene, however, is Hannibal’s intense appreciation for Will’s unknowing understanding of him, or perhaps more accurately Mads Mikkelsen’s ability to convey this appreciation entirely through gesture and facial expression in a way that gives the scene a dramatic arc. But it is not difficult to see why Hannibal would appreciate Will’s assessment - while Will hedges on the hierarchy of Hobbs and Lecter, the question is whether Hannibal elevated Hobbs’s style, not whether art is a higher style. Certainly it’s not a position that Hobbs would accept - from his perspective, Hannibal’s killings, fueled by sadism instead of love, would be “just murder.” But Will does not seem to consider this position - to him, art is self-evidently a higher form of killing, an assumption so obvious he doesn’t even think to interrogate it.

ABIGAIL: Does that mean I’m sick, too?

FREDDIE LOUNDS: You’ll be fighting that perception. Perception is the most important thing in your life right now.

This sets up Hannibal’s manipulation of Abigail at the episode’s climax (although he isn’t here for this line of dialogue, and thus can only know it if one ascribes supernatural abilities to him), but it’s also far more true than Freddie realizes. It would be more apropos still were she to use the phrase “public imagination,” save for the fact that the perception/imagination that ought concern Lounds is very specific in nature.

JACK CRAWFORD: “It’s not very smart to piss off a guy who thinks about killing people for a living.” Know what else isn’t very smart? You were there with him and you let those words come out of his mouth.

HANNIBAL: I trust Will to speak for himself.

And, more to the point, he wants to encourage Will to identify as a guy who thinks about killing people for a living. But the surface-level content of Hannibal’s statement is interesting as well, highlighting the way in which his treatment of Will does not actually involve any sense of responsibility for Will’s well-being or actions. Which is obvious enough to the audience, but, crucially, really should be obvious to Jack as well.

ABIGAIL: So you pretended to be my dad?

WILL GRAHAM: And people like your dad.

ABIGAIL: What did that feel like? To be him?

WILL GRAHAM: It feels like I’m talking to his shadow suspended on dust.

As with many of the show’s more cryptic lines, this interpolates a bit of Harris’s books, where the phrase describes a mostly unsuccessful effort on Will’s part to conjure an image of his quarry. Here it is impossible to parse, save for its sense of ghosts and distance, establishing that the Chesapeake Gothic dreamscape the show takes place in is not a mere convention of cinematography but a fairly direct representation of Will’s lived experience.

ABIGAIL: Can you catch somebody’s crazy?

ALANA BLOOM: Folie a deux.

ABIGAIL: What?

ALANA BLOOM: A French psychiatric term. “Madness shared by two.”

This is obviously a commentary on where things are going with Will and Hannibal, although the circumstances that Abigail describes would generally be referred to specifically as folie imposée, in which one person imposes their madness on another. This is certainly what Hannibal has in mind for Will, but in practice they will form the far more fascinating folie simultanée, in which two separate psychoses come to intertwine and mutually influence one another. In effect, then, the difference between artistic influence and artistic collaboration.

HANNIBAL: One cannot be delusional if the belief in question is accepted as ordinary by others in that person’s culture or subculture. Or family.

This quote, which is almost straight from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, is conspicuously present in the Wikipedia entry on folie a deux, where it’s quoted almost immediately after the imposée vs simultanée distinction. (And yes, this feature of the article predates “Potage.”) Hannibal’s attempt to dissuade Abigail of the idea that her murder (or, if one wants to take an expansive view of what Hannibal is and is not aware of, Will of his, since he tacitly responds to Will’s flashback to Hobbs) is the product of madness is simply motivated: Hannibal does not consider his to be. Or more accurately, he does not consider the categorization relevant to him. And by dint of his newfound familial bond with Will and Abigail, it does not apply to them either.

MARISSA’S MOTHER: Marissa. Come home.

MARISSA: Stop being such a bitch.

As justifications for Hannibal’s murders go, this may be the most specious. He is admittedly looking for an excuse at this point, given that a second copycat murder will increase pressure on both of his current projects, but all the same, it’s unusual for Hannibal to kill someone who isn’t actually rude to him or anyone he cares about.

I could have talked about this in either of the last two entries, but I was waiting for one where I was running a bit short on points for commentary, so here we are. The Stag is the core of Will’s complex dream-mythology of Hannibal, a set of images and hallucinations that will ripen and evolve deliciously over the course of the series. Its origin, obviously, is in Cassie Boyle’s murder, which eventually turns out to be a little odd given that Will has been involved in hunting the Chesapeake Ripper as well. But of course, Cassie Boyle’s murder was for him, “gift-wrapped” as he put it to Hannibal, and so it’s that, not the Ripper, that begins to create an image of Hannibal inside of his head.

Eventually this iconography will evolve, but we’ll get there when it happens.

HANNIBAL: Was he? This isn’t self-defense, Abigail. You butchered him.

ABIGAIL: I didn’t...

HANNIBAL: They will see what you did and they will see you as an accessory to the crimes of your father.

ABIGAIL: I wasn’t.

HANNIBAL: I can help you, if you ask me to.

The Luciferian temptation involved here, complete with the heavily performative move of making Abigail ask for the help that he’s already offered, is a routine move for Hannibal, although it lacks what will become the defining line. On one level this is straightforward manipulation: Hannibal seeks to create a sense of debt and obligation in someone by dint of injecting himself into a situation where they kill someone. (Often a situation he’s helped engineer, though his involvement in the Nicholas Boyle situation is negligible.) The hidden factor in the resulting devil’s bargain is that Hannibal’s targets generally wrongly assume Hannibal would be as reluctant to kill them as they would be to kill him. Note also, however, the superhuman perception and creation of a plan involved in Hannibal’s knocking Alanna out. As with everything, it doesn’t strictly require that we read Hannibal as possessing supernatural abilities, but it’s a lot easier than trying to work out what Hannibal’s actual moment-to-moment thought process would be here.

ABIGAIL: They think who called the house was a serial killer. Just like my dad.

HANNIBAL: I’m nothing like your father. I made a mistake. Something easily misconstrued. Not unlike yourself.

Hannibal is pushed to an outright lie here, although he mixes it with a deeper truth in his disavowal of the similarity between himself and Abigail’s father. We have already unpacked the substance of this distinction. Hobbs’s killings are based out of mere pathology, some unresolvable issue in his emotional relationship with Abigail that required cannibalistic murder to work through. Hannibal, on the other hand, has contempt for his victims, which allows him the distance needed to create art. The vehemence with which he rejects the comparison, however, reflects his underlying anxiety about the accusation, an anxiety also reflected in his need to replace Hobbs for Abigail in lieu of actually consuming him.

April 8, 2017

Saturday Waffling (April 8, 2017)

Just a heads up to everyone in case you're just sort of sitting there going "oh, the Patreon always hits whatever goal Phil sets," we're currently only $1 over the threshold where I'll be reviewing the next season of Doctor Who. And that's because someone upped their pledge from $1 to $9 to ensure it would happen. Basically, what that means is that if anyone's payment doesn't go through at the end of the month, reviews will stop. Meanwhile, We're a whopping $19 away from me doing podcasts for every episode, which is starting to look like it probably won't. So this is a post, a week before the series starts, where I conspicuously link the Patreon in the hopes that you'll go contribute.

I know that the world is awful and there are better things to spend money on than this site. And I'm honestly OK with not doing podcasts, or hell, not doing reviews. The idea of watching Moffat's last season with the same intellectual privacy I watched his first has a real appeal. Equally, the podcasts were a blast last year and it just wouldn't feel like a season of Doctor Who without it completely taking over the site, y'know? So I hope you can find a buck or two in your budget to toss towards the Patreon, because I'd like to do these things. But they take time, and there isn't enough of that in my life at the moment.

In other news, work continues on both Neoreaction a Basilisk and Eruditorum Volume 7. The former will be out this summer, the latter hopefully this year. I'll get back to Last War in Albion after Neoreaction a Basilisk is out the door, but that's occupying my "write extra stuff" time. (Well, this month I'm just being naughty and writing the first chapter of my cyberpunk book because I haven't had time to write something for myself in a year now and I deserve it.)

Anyway. Thanks to everyone who does support the site, and who supports Jack and Josh in their endeavors. It's a pleasure writing for you all. And if you do want Eruditorum Presscasts for Season Ten of Doctor Who, here's that conspicuous Patreon Link again.

See you next Saturday, hopefully.

April 7, 2017

Podcasting Round-up

No proper post today, sadly. Too busy. There is some more stuff in the pipeline, and it's not all about Rogue One. But for today you'll have to be content with a round-up of recent podcasts of mine.

No proper post today, sadly. Too busy. There is some more stuff in the pipeline, and it's not all about Rogue One. But for today you'll have to be content with a round-up of recent podcasts of mine.

Firstly, I was recently a guest (again) on the excellent They Must Be Destroyed on Sight! movie podcast, joining Lee and Daniel to talk about the Coen Brothers' 1996 masterpiece Fargo. Check that out here.

(You may recall I wrote something about Fargo once upon a time, that can be found here.)

My previous appearances on TMBDOS (tmbdos!) can be found here (Blood Simple & Blue Velvet) and here (both versions of Nosferatu).

Also, there's Shabcast 30. I gave this a rather desultory write-up when I posted it last week, because I was feeling cheeky. And, it being a little unusual, I wanted listeners to encounter it without any expectations. But it's actually a fun episode, if very, very long. Myself, Kit, and Daniel (with a brief guest appearance by James) discuss Series 1 and the Ninth Doctor... with various detours along the way... while in various stages of inebriation. It's a little early to say, but it may end up being a kind of pilot for a new format, the Drunken Whocast. We'll see.

The most recent Wrong With Authority didn't get the downloading love I hoped for and expected, which is a shame since it's our best yet (as of writing). The gang talk Shadow of the Vampire (y'know... the movie about the making of Nosferatu where the vampire is real) and Gods and Monsters (about legendary horror director James Whale, played by Gandalfneto). Download here. And check out the back catalogue if you haven't already.

And, last but not least, there's the most recent episode of Oi! Spaceman, on which I guested to talk about 'Rose' and 'The End of the World'. Just in case Shabcast 30 isn't long enough for you, you can also listen to more of me talking about Who 2005 here.

Nasdrovia!

April 5, 2017

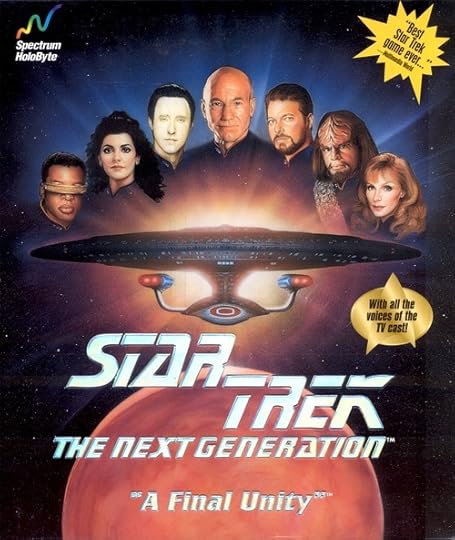

Flight Simulator: Star Trek: The Next Generation - A Final Unity (PC, Mac)

If you enjoy seeing me talk about video games, might I direct you to my new YouTube Channel, where I hope to do a great deal more of that in the near future? I also now have a Patreon of my own to go along with that, so should you choose to support me in any way I will be most gracious.

If you enjoy seeing me talk about video games, might I direct you to my new YouTube Channel, where I hope to do a great deal more of that in the near future? I also now have a Patreon of my own to go along with that, so should you choose to support me in any way I will be most gracious.

We've talked at length about the odd role the PC plays in the history of the video game medium in this project before. In brief, my argument goes something like this: Despite the fact the first widely available interactive electronic games were made as programming experiments for personal computers, they're not, broadly speaking, “video games” in the way I personally conceive of them. There are two discrete traditions that make up what we call “video games” today, and a lot of the tension in video game culture probably stems ultimately from this: One comes from those early PC programming experiments and is largely European in origin, stemming from what is called bricolage couture in French. A branch of this took root in the United States where it syncretized with the liberalism-inspired New Age and Hippie movements and the country's penchant for solipsistic ego-mythologizing to give rise to Silicon Valley.

The other, by stark contrast, traces its lineage to places as disparate as the cathode ray tube manufacturing industry, public houses and amusement arcades and has become most associated with (and defined by) Japan and Japanese culture. The quick and dirty rule of thumb for determining which tradition you're dealing with when you play an electronic game is to pay attention to the basic gameplay, with the divide more or less being over whether the game privileges real-time action or text-driven interaction and logic puzzles. Or, put another way, which does your game more closely resemble at its most fundamental level, Zork or Asteroids? I'm oversimplifying things to a massive degree here, and as the years have gone on there's naturally been a lot of overlap and syncretism between these two styles, and most modern games are pretty hard to peg as being one or the other and not both to some degree. But the divide is still there, and I submit you can't understand the history of the video game industry without being aware of it.

(I would like to stress here that I have never desired to place a *value judgment* on either of these two basic modes of gameplay: I may have my personal preferences, but I think they both have their own situational strengths and weaknesses that deserve to be acknowledged and talked about.)

The PC then is both one possible origin point for the modern video game industry and yet also occupies a weirdly limnal place within it. There's no disputing early PC games were developed by and for a very specific audience [straight, cis wealthy, nerdy (they tend to be the same thing anyway) WASPy men], but the old joke in games journalism was that once consoles became the norm the PC *always* got the shaft with dramatically inferior ports of console games (though ironically enough in recent years, as of this writing, the PC has become the *lead platform* for many developers due to modern consoles becoming, in essence, shitty PCs). By 1995, however, things had changed somewhat. Cyan Worlds' groundbreaking Myst, which blew the door off the PC gaming market by opening it up to an entirely new audience (read: normal people) by dropping players in a world meant to be explored, puzzled over and immersed in (and becoming one of the best-selling video games of all time in the process), was two years old by this point. With the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and SEGA Genesis being seen as children's toys first and foremost in a way even their predecessors had never been (and, in 1995, very much on the way out), the spotlight was now on the PC to deliver interactive electronic experiences for sophisticated adult sensibilities.

Star Trek is actually a really good case study here, as its history of association with the video game industry goes all the way back to the beginning and spans both traditions, but has historically been way more comfortable with one over the other, and not always for the best of reasons. Star Trek's connection to the PC and PC gaming culture is primordial, so a premier Star Trek game for the PC market of the mid-90s had some serious potential for crossover success. The deeply ironic reality then is that Star Trek: The Next Generation- A Final Unity is in a lot of ways Spectrum Holobyte's second draft of Star Trek: The Next Generation - Future's Past and Echoes from the Past, two games for the Super Nintendo and SEGA Genesis, respectively, from last year. All three games feature a treasure hunt to find an ancient artefact of great power, with various galactic powers vying for its control. All three games have you hopping about the galaxy playing all of the Galaxy-class Enterprise, though A Final Unity does weave its errand-running into its narrative noticeably more elegantly than its home console predecessors. All three games involve a Gene Roddenberry-esque Challenge of Worthiness put on by aloof, semidivine aliens in the climax, and all three games feature Spectrum Holobyte's original alien culture, the Chodak, in prominent roles.

Despite being essentially a bigger-budget remake of a game for the “kiddie” home consoles, A Final Unity's status as a PC exclusive got it a lot of attention from “grown-up” fans. Its ambitions become readily apparent once you dig into the history of the project and learn it emerged from the ruins of a canceled game for the 3DO called Star Trek: The Next Generation - A World For All Seasons. The 3DO was a short-lived home console from the fourth generation that set to compete directly with SEGA and Nintendo, overtly marketing itself as the luxury ticket alternative video game system for refined adult tastes, explicitly taking aim at the Genesis and Super Nintendo's reputation as children's toys. The problem was nobody bought a 3DO because it was $700 and the only things you could get for it were bizarre pornography, terrible full-motion video games and ports of stuff you could already play on the PC and didn't cost $700. But A Final Unity leveraged the grown-up appeal of its ancestor, awkward as it was, all the way to the hilt, featuring a fully voiced experience with the entire cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation, a script looked over by Naren Shankar and enthusiastic marketing that talked it up as the “Best Star Trek game ever”.

That's debatable, but Star Trek: The Next Generation - A Final Unity is certainly very good and very impressive. There's no doubt I would have loved this had I been able to play it in 1995. Like its two predecessors, A Final Unity plays out as a kind of Next Generation version of the Star Trek: 25th Anniversary adventure game from the early 90s (though once again the space combat portions are sadly nothing to write home about, but I guess that just encourages you to find other, more peaceful solutions to the game's puzzles), and in fact this one wears its pedigree on its sleeve far more than either of the two prior Spectrum Holobyte games. This is due to not just the culture of the platform it found itself on but the tech specs as well, allowing A Final Unity to *look* way more like a, well, a next generation update of that style of gameplay. The fully voiced FMVs (“full-motion” prerendered video sequences) are impressive for the time, and really sell the conceit that this is a lost Star Trek: The Next Generation episode.

From a Star Trek perspective one thing that struck me as interesting is how much the Romulans, and peace with the Romulans, plays into the game's main story. There's a female Romulan commander deuteragonist who crops up every so often and plays a part in the aforementioned climactic Challenge of Worthiness, and her fate is incumbent on your actions as the player. A Final Unity would certainly be an interesting piece to compare with Star Trek: Deep Space Nine - Blood & Honor, except for the curious fact the Romulans aren't actually *called* Romulans in this one, despite using obvious Romulan Warbirds. Instead, they're called "Garidians", supposedly an either an offshoot group or an allied political faction. It makes me wonder if Spectrum Holobyte and Naren Shankar were uncomfortable using the vanilla Romulans for this comparatively more sympathetic portrayal because of how their characterization had been flanderized over the course of the Star Trek: The Next Generation TV show.

I also really want to praise the art design in this game because it's really fun and imaginative. The different planets especially are all wonderfully creative and memorable-My favourites are a surreal alien jungle world and the Chodak security station, which reminds me of Where in Space is Carmen Sandiego?, or maybe the old Looney Tunes Marvin the Martian short “Hare-Way to the Stars”. All of the environments are bright, colourful and animated with impressive detail: The mid-90s was really the last vanguard of hand-drawn graphics in video games across the board before being deprecated wholesale as the industry shifted focus to rabidly chase the dragon of photorealism with polygon graphics at all costs (including, it would seem, their profits and the livelihoods of countless development houses, but that's a story for another place). Star Trek: The Next Generation - A Final Unity shows the video game industry at this transitional point quite clearly, mixing hand-drawn environments and sprite art with computer generated FMVs and prerendered backdrops in certain areas, occasionally to the point of a jarring stylistic clash. In fact, if I were to imagine a home console that would be a good fit for this game, it wouldn't be the 3DO, but the SEGA Saturn, a machine whose fate was defined like nothing else by this historic cultural sea change.

Which brings me back to something I teased above. I said “if I played this game” back in the day I would have loved it. A Star Trek: The Next Generation game in the style of Star Trek: 25th Anniversary? That would have overjoyed me beyond all reason. But of course I didn't play it. I couldn't. I did, in fact, have an up-to-date computer in 1995 (I got it that very year, in fact), but it was a Power Macintosh, a platform well-known of course for its robust gaming pedigree (and for all you non-gamers, I'm being painfully sarcastic). And while there was a Macintosh port of Star Trek: The Next Generation - A Final Unity, I certainly never saw it in stores. That's not to say I didn't look: I was aware of its existence through ads in my comics and magazines and I made a point to look for it whenever I went out shopping. You have to remember I grew up in a very rural area, so pickings for things like video games were slim. We didn't have Internet, and even if we did online shopping wasn't really a thing back then. The nearest electronics store was an hour away and I didn't find out about it until years after this game came out, and the only other option were bookstores and office supply places that occasionally had a small handful of PC games in stock every so often. So sure you could find stuff like Myst, but that was about it.

And that's another thing about PC games: Archival and backwards compatibility are, quite frankly, not what they should be. You wouldn't think this would be the case, what with the PC supposedly being an open platform as opposed to those evil, closed box home consoles and all that. But in the long run, home consoles have proven themselves *far* more resilient and robust in a lot of different areas. PC hardware is designed to break, and planned obsolescence is baked into its very DNA: I have confidence that any Nintendo console I buy that's older than 2001 will probably last until the heat death of the universe. That's just the way those machines were built. But my computer? Well, as of this writing I have a laptop I just bought last year, and it's already having power management issues.

The same is true for the ROM cartridges all the games for those old consoles ran on. While here in 1995 ROM cartridges are going to become the epitome of uncool in just a few months when the launch of the Sony PlayStation introduces everyone to the tantalizing power and storage capacity of the mighty CD-ROM, in twenty years all those hip and fancy "discs" are going to be staring down the spectre of “disc rot”. Disc rot is a decidedly frightening phenomenon wherein the chemicals binding the reflective surface of optical discs decohere, rendering the disc unreadable and irreparable. Counterintuitive as it may seem, all those old, primitive game carts from the 1980s are going to last way longer then the shiny compact discs and DVDs of the 90s, or the Blu-rays of the 2000s and 2010s, and we're facing the very real possibility of entire generations of games, data and other media simply vanishing with no way of preservation or recovery because of our technofetishistic overeagerness to adopt optical discs as “the next big thing” in the 1990s.

So the fact remains, if you're looking to play Star Trek: The Next Generation - A Final Unity today, you're pretty much up a creek. Good luck finding a modern PC that'll even be able to read that 1995 state-of-the-art Multimedia CD-ROM, provided, that is, you manage to track down a copy that still works to begin with. And that's even before you take into consideration operating systems programmed to work on specific architecture: A Final Unity was made for DOS and and an obsolete standard for Mac OS systems, but no modern PC *or* Macintosh is backwards compatible with those systems anymore so your only solution nowadays is really emulation through something like DOSBox. But emulation introduces inauthentic quirks by the very nature of what it does, and if you're like me and view DOS as basically some mystical arcane dead language that requires a doctorate to understand, your only other option is if you're lucky enough to still have a workstation from the mid-90s banging around for some inexplicable reason (as I thankfully do, so I could theoretically run the Macintosh version of this game if I ever found it, though I have no idea if it's properly up to spec), in which case you're hauling out a behemoth of a hardware tower with questionable functionality for a few minutes of curious amusement.

To be perfectly honest, I dread having to cover PC games on Vaka Rangi, because I know all of the games historical enough to warrant talking about are upwards of twenty years old and that it is a near-certainty I'm not going to be able to get them to run without a truly desperate amount of effort, if at all. And if I don't, I'm going to have to make up a bunch of extra stuff tangentially related to the game to cover for the fact I can't talk about it with the authority I can other things. Like I just did here. Meanwhile, I look over at my home console collection and know that I have a plethora of absolutely hassle-free options available for taking anything from the Nintendo GameCube generation and earlier and getting it up and running flawlessly in literally seconds. So I ask you. If you wanted to get a vintage Star Trek: The Next Generation fix in video game form, which of the two Spectrum Holobyte outings I've looked at so far would you feel more comfortable checking out?

I've made my case. But your path, as always, is up to you.

April 3, 2017

The Proverbs of Hell 2/39: Amuse-Bouche

We're currently $11 shy of Doctor Who Season Ten reviews on Patreon, and $31 shy of podcasts. It's probably not quite that bad, as there are some declined pledges from March that will hopefully straighten out, but if these are things you want, please support the site by backing it on Patreon.

We're currently $11 shy of Doctor Who Season Ten reviews on Patreon, and $31 shy of podcasts. It's probably not quite that bad, as there are some declined pledges from March that will hopefully straighten out, but if these are things you want, please support the site by backing it on Patreon.

AMUSE-BOUCHE: Literally “mouth amuser,” its function is much the same as an apéritif, but it is a bite-sized food item and thus more substantial, in much the same way that this episode, liberated from the amount of setup and exposition that “Apéritif” had to do, gets to be. A stuffed mushroom cap would be an entirely appropriate choice of amuse-bouche.

The tiered concrete at which his students sit give the sense of Will having retreated back into the bone arena of his skull.

The show’s distinctive establishing shots are as important as its richly saturated color palette in creating its Chesapeake Gothic atmosphere. The time lapse establishing shots, with clouds whizzing overhead, frame what happens as taking place outside of time, in a fractured dreamscape. Fractured time is a recurring motif in the show, where it serves to indicate the blurring of internal and external landscapes. Here the process is virtually literal.

HANNIBAL: You saved Abigail Hobbs' life. You also orphaned her. It comes with certain emotional obligations, regardless of empathy disorders.

WILL GRAHAM: You were there. You saved her life, too. Do you feel obligated?

HANNIBAL: I feel a staggering amount of obligation. I feel responsibility. I've fantasized about scenarios where my actions may have allowed a different fate for Abigail Hobbs.

An endearing quirk of Hannibal’s pathology is that, while he certainly will lie when it’s required of him (“Pork,” for instance.), he prefers not to. This speech is one of the most nuanced. The second two claims are reasonably straightforward - especially “I feel responsibility,” although “fantasized” is the funniest of them. The first, however, is the interesting one, simply because it is honest. Hannibal really does feel just as much paternal attachment to Abigail as Will following what happened. Where Will (somewhat wrongly) views her as something like a human version of one of his rescued dogs, Hannibal is well aware that Jack’s suspicions of her are correct, and his paternal attachment is much more similar to her actual father’s. Which is to say, he both wants her as an apprentice and potential meal.

BEVERLY KATZ: Zeller wanted to give you the bullets he pulled out of Hobbs in an acrylic case, but I told him you wouldn't think it was funny.

WILL GRAHAM: Probably not.

BEVERLY KATZ: I suggested he turn them into a Newton's Cradle, one of those clacking swinging ball things.

WILL GRAHAM: Now that would have been funny.

Will’s sense of humor foreshadows his affection for Hannibal, whose aesthetic in his murder tableaus is not entirely dissimilar to making a Newton’s Cradle out of the bullets that killed Garret Jacob Hobbs.

JACK CRAWFORD: Lecter gave you the "all clear." Maybe therapy does work on you.

WILL GRAHAM: Therapy is an acquired taste I have yet to acquire but sure served your purpose. I'm back in the field.

Jack is torn between being too ruthless not to snap up the opportunity to get Will back in the field and too moral not to try to take care of Will. Here he’s confronted with the reality that Hannibal rubber-stamped Will back into the field and chooses to ignore it in the hope that Hannibal proves useful to Will despite having cavalierly tossed him into action. In fact Hannibal represents the least happy medium possible between Jack’s two desires, although it’s safe to say that Will is going to acquire the taste eventually.

As Hannibal transitions into the somewhat awkward case-of-the-week structure it will pretend to have for its first season, it leads with an absolute stunner. Stammetz’s M.O. is brilliantly inventive and weird, and we’ll get to the ways in which it’s a brilliant choice for Hannibal specifically. But it also comes with a spectacularly unsettling visual in the form of the mostly decomposed mushroom people. The body horror involved is as intense as anything Human Centipede (a series I will never cover on Eruditorum Press, but would call the series “Incremental Progress” if I did) has ever offered, and in a way that can clear network standards and practices to boot.

This particularly outlandish choice for an initial case-of-the-week presentation further solidifies the unreality of the show. Simply put, this clearly isn’t happening in the real world.

HANNIBAL: Is it harder imagining the thrill somebody else feels killing now that you've done it yourself?

WILL GRAHAM: Yes.

There is considerable ambiguity over what this difficulty is, and Hannibal does not probe it further. It jars appreciably with Will’s later admission that killing Garret Jacob Hobbs felt good, a fact that seems like it should be more or less equivalent to saying that it’s easy to imagine the thrill of killing. (Or, as Hannibal and Will both put it later, a “sprig of zest.”) Two ways out of this exist. The first is to read “harder” not as performance but as emotional exertion - thinking about killing is more taxing on Will now. This is self-evidently true, and thus fairly uninteresting. The second, meatier option is to read the difficulty in imagining, whether because Will’s own thrill interferes or because his newfound appetite for killing means that the thrill feels as though it is situated in nature instead of in imagination. If killing is simply a desire of meat then it is no longer something that Will’s vision conjures into being when reading a murder: it is simply there, as much a part of the scene as the blood.

HANNIBAL: The structure of a fungus mirrors that of the human brain. An intricate web of connections.

This similarity is obvious and the source of a non-trivial number of sci-fi concepts, but crucially is based entirely on appearance. The physical structure and visual appearance of the nervous system and fungi are indeed similar, but there is no actual similarity of function. And yet this fact seems wholly irrelevant to proceedings. Stammetz’s theories are treated as being roughly as credible as Garret Jacob Hobbs’s love for Abigail. But that’s a controversial extension of human empathy, not science-defying mysticism. But consider Hannibal’s visual aesthetic and the unreality of its spaces. In the context of its gothic dreamscape, the visual resemblance is a substantive one.

Also likely is that while mushroom people can clear standards and practices, the Terence McKenna angle they actually want to go for wouldn’t cut it. On the other hand, “Œuf.”

FREDDIE LOUNDS: I’ve never seen a psychiatrist before and I'm unfortunately thorough. So you're one of three doctors I'm interviewing. It's more or less a bake-off.

HANNIBAL: I’m very supportive of bake-offs.

Hannibal’s propensity to covertly admit to being a cannibalistic serial killer occasionally lead him to make statements about food that are strangely suggestive without actually leading anywhere.

HANNIBAL: You've been terribly rude, Miss Lounds. What's to be done about that?

This is the first time Hannibal’s method of victim selection is alluded to (the fact that Cassie Boyle once blew smoke in his face having been relegated to DVD commentary, although it was a lucky break for him that he knew a rude person in Minnesota that also fit Garret Jacob Hobbs’s pattern). Freddie, of course, is terribly rude quite often, at least by Hannibal’s standards, which makes his continual indulgence of her existence difficult to explain.

WILL: What were you gonna do to her?

ELDON: We all evolved from mycelium. I'm simply reintroducing her to the concept.

WILL: By burying her alive?

ELDON: The journalist said you understood me!

WILL: I don't.

ELDON: Well, you would have. You would have. If you walk through a field of mycelium, they know you are there. They know you are there. The spores reach for you as you walk by. I know who you're reaching for. I know. Abigail Hobbs. And you should have let me plant her. You would have found her in a field, where she was finally able to reach back.

Eldon’s pathology, based, as Hannibal surmises earlier in the episode, on the resemblance between fungus and the human brain, is hazily defined, essentially sketched out entirely in the disjointed monologue Stammetz gives in this scene. Nevertheless, it’s a beautifully multilayered idea. The notion of reaching and connecting people ties directly to Will’s empathy, which is of course what leads Stammetz to target Abigail. But equally important is the fact that Stammetz uses food to make the connection. In an episode whose real purpose is to begin to establish the connection between Will and Hannibal, Stammetz is an extremely apt choice of killers.

WILL GRAHAM: I thought about killing him. I'm still not entirely sure that wasn't my intention pulling the trigger.

HANNIBAL: If your intention was to kill him, it's because you understand why he did the things he did. It's beautiful in it's own way. Giving voice to the unmentionable.

Hannibal’s yearning to connect with Will over the aesthetics of murder is touching. But “giving voice to the unmentionable” is an atypically lame summary of what Stammetz’s work involved. Sure, the possibilities of new communication were central to his gardening, but the idea that he was revealing some gothically suppressed truth is a stretch. In this regard, Hannibal is projecting on Stammetz as much as he is on Will.

HANNIBAL: It wasn't the act of killing Hobbs that got you down, was it? Did you really feel so bad because killing him felt so good?

(pause)

WILL GRAHAM: I liked killing Hobbs.

HANNIBAL: Killing must feel good to God, too. He does it all the time, and are we not created in his image?

WILL GRAHAM: Depends who you ask.

HANNIBAL: God's terrific. He dropped a church roof on thirty-four of his worshippers last Wednesday night in Texas, while they sang a hymn.

WILL GRAHAM: Did God feel good about that?

HANNIBAL: He felt powerful.

Taken from Hannibal’s letter to Will late in Red Dragon, this is one of the show’s bolder uses of the books, burning off a fairly iconic moment as the closer to its second episode. The show’s relationship with God is an interesting one. The natural gravity of Hannibal is towards Milton’s Satan, and the show finds itself inexorably drawn towards Christian iconography. On the other hand, the show is decidedly not Christian, and its vision of God is largely established here. It’s not a deistic, distant God - he dropped the roof, as opposed to letting it fall. Rather, it is one of almost malevolent indifference/Otherness. Hannibal actively distinguishes feeling powerful from feeling good, preventing the straightforward reading of an actively evil God who is motivated by a desire for power. And yet God’s reason for killing thirty-four people in Texas remains unknown and unknowable.

Although Hannibal has some ideas.

March 31, 2017

Shabcast 30

March 29, 2017

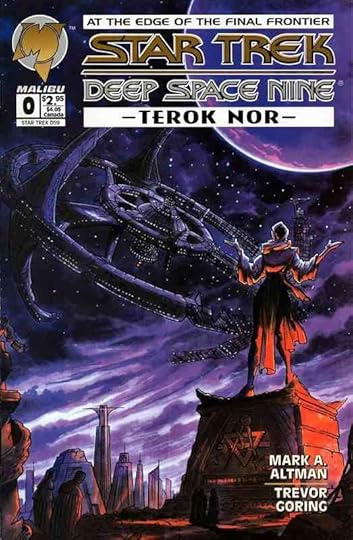

Myriad Universes: Terok Nor

Jadzia Dax and Doctor Bashir are taking time out from a camping trip in the Bajoran wilderness to visit a museum honouring the planet's art, history and culture. Jadzia compliments the beauty of one of the pieces, whereas Julian tries to act like an art critic to impress her with his “knowledge” of different Bajoran styles. Jadzia is exasperated and, perhaps sensing he's fucked up, Julian changes the subject. He asks her if any of her hosts went on class field trips to museums as children. Standing atop a towering balcony, the two gaze down into the museum below, where it just so happens one such field trip is underway right now.

Jadzia Dax and Doctor Bashir are taking time out from a camping trip in the Bajoran wilderness to visit a museum honouring the planet's art, history and culture. Jadzia compliments the beauty of one of the pieces, whereas Julian tries to act like an art critic to impress her with his “knowledge” of different Bajoran styles. Jadzia is exasperated and, perhaps sensing he's fucked up, Julian changes the subject. He asks her if any of her hosts went on class field trips to museums as children. Standing atop a towering balcony, the two gaze down into the museum below, where it just so happens one such field trip is underway right now.

It's a large room, full of gigantic statues, all looming imposingly over the museum guests. A teacher is disappointed in her students, none of whom recognise the figure immortalized in stone before them. Her name was Charna Sar, who she says was a great hero of the Bajoran people whose name has been forgotten. The children wish to hear her story and the teacher obliges, but only on the condition they will continue to tell it themselves. The teacher begins the tale, saying the story of Charna Sar is intimately connected to that of a Cardassian by the name of Kotan Darek. We transition to a flashback, and return to the darkest days of the occupation. Darek has arrived at a prison camp, wishing to speak with a Bajoran prisoner named Charna Sar, which takes the camp's commandant by surprise. Charna is a resistance member who's been captured and sentenced to death, but Darek wants to pardon her, shocking both Charna and the commandant.

As they leave the camp, Darek explains that he's been ordered to construct a orbital space station around Bajor that will serve as an ore processing facility. In addition to being in the resistance, Charna Sar is also Bajor's greatest architect, and Kotan Darek wants her to help him build it, as well as serve as a liaison to the Bajoran labourers. Charna flatly refuses on the grounds the station would further the explotation and enslavement of her people, but Darek protests that the station will in fact automate the mining process, thus making life easier for those on the ground in the mines. Charna still isn't convinced, but complies after Darek threatens to destroy the Barodeem, a library tower containing historical and cultural artefacts dating back centuries with a phaser blast (Darek then claims, however, that he would never have actually done it). The two leave for the station, which is already under construction. Darek says that it will be “the eyes and ears of Bajor and Cardassia's greatest aesthetic triumph”.

Darek takes Charna aboard, showing her a common area under construction, and shows her the opulent quarters she's been assigned, right next to his. After Darek leaves, Charna compliments his taste in clothing, and takes a look at the future Terok Nor's schematics. In keeping with a previous comment she made about the station being “typically Cardassian” and “function over form”, she extends the lengths of the docking pylons and takes a look at the air filtration systems. Meanwhile, Darek is in communication with a Gul Dukar, who is less than pleased with his employing of a Bajoran terrorist to help design their ore processing facility. Dukar says he should be alerting the Obsidian Order, but instead tells Darek to have Charna executed once she's done, to which he agrees.

The next day Darek goes to see Charna first thing in the morning. As they make their way to Operations, Darek says he's found out about the changes she's made to the blueprints, and agrees with her alterations: Both respeccing the ventilation units to alleviate the strain on the Bajoran workers and her other design alterations. Soon, they meet a former comrade of Charna's, a woman named Hester, who's not happy to see her working with Darek, which she views as collaboration. Darek points out that while Charna may see her work on Terok Nor as helping the cause, Hester probably doesn't view it the same way. Charna later goes to try and talk things over with her by way of explaining, but Hester won't hear any of it. That is, unless, she's willing to fight on the frontlines again. Charna gives the Bajoran resistance fighters the schedule of a group of supply ships, which does not go unnoticed. She's formally disciplined in the Cardassian way (that is, brutally), but all Darek wants from her is to promise not to destroy Terok Nor until after it's finished.

Darek takes Charna to his quarters, and shows her a hologram of the Obsidian Order headquarters, which he both designed and built. It was his greatest masterpiece, before Terok Nor, which he wants them to finish as quickly as possible: By working with a Bajoran, he's made powerful enemies within the Cardassain government, and his allies will no longer be able to protect him. Charna is baffled that he would throw away his career for her, and asks him why. “Because we are the same,” Darek says. “Fate has made us enemies, but destiny has allowed us to pursue our love together. The creation of shape and form. To make something new from nothing, the power to build”. “How I would love to believe that”, Charna responds, “But you Cardassians have mastered an art that eludes us Bajorans, the art of destruction”. “That is the way of my species, and I must accept that”, he answers.

One month later, Terok Nor is finished, with both Charna and Darek marveling at how beautiful it is. Even so, Charna doesn't want to be associated with it, claiming it's “a product of Cardassian brutality, not Bajoran ingenuity”. Just then, Darek is summoned to meet with Gul Dukar, but warns Charna of something about him before he goes, though we don't get to hear what it is. In the newly completed prefect's office, Dukar relieves Darek of command without advance notice. The architect is then ordered to move *every Bajoran* on the station to Cargo Bay 6, again with no explanation. Indeed, Dukar even snarls that if he didn't have friends in high places, Darek would be going with them. Dukar presses the Gul for the reasons why, and the infuriated commander spits out that Darek has compromised the safety of the entire station by employing Bajoran construction workers, and now they must all be disposed of. Darek leaves to fulfill his duty.

Gul Dukar takes his young son to watch the execution via viewscreen looking in on the cargo bay. Dukar plans to depressurize the cargo bay, thus suffocating all the Bajorans inside. The child asks why not simply shoot them, and his father calmly explains that this way they can make it look like an accident. “What about the children?”, his son asks. “What of them?” the Gul asks in response. But before he can act, an elite team of Bajoran resistance fighters in stealth suits breaks into the Operations centre. Dukar orders them all killed and fires the first shot, cutting down one of the freedom fighters. The leader of the strike force responds by gunning down the Gul himself. Then Darek exclaims he'll depressurize the bay if they resistance fighters don't drop their weapons, and the leader tells her team to do as he says.

The next day, it's revealed the resistance leader was, of course, Charna Sar, and, of course, Darek knew about it. They both comment on the roles history has forced them into playing. She knows he has to execute him, but he saved her people, which is all she cares about. And when they comment on the fate of Gul Dukar's son, who “will continue the vicious chain, seeking the blood of Bajorans in vengeance for what he witnessed”, Charna implores her equal and opposite to tell the boy and all the others “Tell them what we had together. Bajorans and Cardassians must know that there is something better than hate. Something more than enmity”. He will, and promises to make her death painless. And she knows he will. Darek's last words to her: “Through Terok Nor, Charna Sar, you will live forever...I will miss you”.