Philip Sandifer's Blog, page 50

May 25, 2017

Eruditorum Presscast: Extremis

I'm joined by Jack Graham to talk Extremis. It doesn't so much go off the rails quickly as never actually manage to find the rails in the first place. You can download that here if you're so inclined.

May 24, 2017

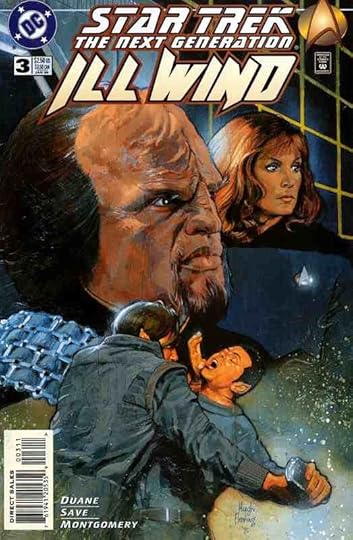

Myriad Universes: Ill Wind Part Three

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship's internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that's how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship's internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that's how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi can pick up thermal signatures from the sensor feed through his VISOR. Although he can't yet get much on the figure itself, he can tell it's carrying a plasma bomb, though it hadn't yet been armed (which explains why the ship's sensors didn't immediately detect it as well). Once the figure enters the shuttlebay, Geordi can get more information because the sensors are more sensitive there. That the figure's internal body temperature of 320K confirms it is most certainly not human: Worf asks “Is 320K bad in human terms?”, to which Doctor Crusher responds “It's dead in human terms”. Furthermore, Bev can discern that the figure has no heart and no stomach but does have “a selectively absorptive gut”, a “nondiastolic perfusion system” and six kidneys. Unusual and excessive for a humanoid, but not for the Carrighae. In other words, this person is a Carrig disguised, albeit somewhat clunkily, as a humanoid in order to throw suspicion onto one of the other teams.

Such a breach of the ethics agreement as attempting to murder one of the other teams is an automatic disqualification, so Worf, Geordi and Beverly go to see Captain Picard. Surprisingly, Jean-Luc decides to not do anything at all...At least not until the end of the race. His first explanation is to glibly state that the information must be “properly authenticated” and ensured that it goes through all the necessary channels. Of course, this also means that the Carrighae will have to “sweat and strain like all the rest, assuming that they do sweat”. After everything runs its natural course, Captain Picard will then turn the information over to race officials. When Geordi asks what will happen if the Carrighae win, Captain Picard says “All the better. Just imagine their reaction when they discover what their own dirty trick has done to them. Let them go home and file litigations until they're blue in the face, or whatever color they routinely turn at such times. Starfleet will tell them where to get off, and in short order, too”.

Worf asks if this counts as vengeance or retribution. Jean-Luc insists that it's justice, but that “sometimes it's more of a pleasure serving it than others”. Worf tells the Captain that with a bit more work, he'd make a fine Klingon.

Later, Deanna Troi comes to visit Captain Picard in the ready room. She's still feeling sleepy, but she can manage. She's more interested in talking to him about him, as she can tell the Mestral's words have hit a nerve. He calls her “dangerous” and “powerful”, and wonders if couldn't have stood to be a bit more dangerous himself. Perhaps he's played his life more safe and complacent than he needed to have done, and, if he had made other choices in his past (such as, say, not giving up solar sail yachting when Starfleet asked him to), he might have been able to realise more of his potential as a person. He fears he may have sold out too quickly, and wonders if, at the very least, he could have fought a bit more with Starfleet over principles and freedoms. More than anything else, he finds it disturbing to be confronted with desires and feelings he thought he'd left behind years ago.

Deanna posits, and Jean-Luc agrees, that his real concern is not the thoughts themselves, but the fact he's having them at all. She argues that emotions have cycles, and all people go through periods of certainty as well as those of doubt, and the cycles can be affected by external stimuli, like other people and situations. “At such times,” she says, “the certainties seem stronger, the doubts deeper...” and he finishes her sentence “When in reality, they're no worse than usual”. The two walk back onto the bridge, where Worf has news that the Mestral's tender has successfully been serviced bu the pit crew, and is on its way back to the race course. The Enterprise phones her yacht to deliver the good news, which shes quite relived to hear.

While the Mestral's crew prepares to ride the next flare, back on the Enterprise Doctor Crusher asks Captain Picard to visit her in sickbay. Jean-Luc hands the bridge over to Will and Deanna, the latter of whom is suddenly startled by something. She says she felt something like distress, though not exactly, but she's not sure who it was. It turns out that Deanna is who Doctor Crusher wanted to talk to Captain Picard about, namely those fits of “sleepiness”. Bev ran some scans on her central nervous system, and the EEG results show that something is interfering somehow. In fact, there's a whole other sleep cycle overlapping hers, and there's no indication as of yet where it came from or how it's doing that. Doctor Crusher is particularly concerned because Deanna had trouble sleeping last night, indicating that this second cycle is having an adverse effect on her own. Since Deanna seems to be the only one affected, Captain Picard asks if it could be something she picked up on a previous mission, but Doctor Crusher doesn't think so. Although it doesn't look serious just yet, Bev will keep Jean-Luc updated if she gets any new information.

Back on the Mestral's yacht, the crew is navigating the new solar flare, attempting to overtake the Kelebrek. The Mestral asks for the secondary sail to be held in position for the time being (she'd rather lose some ground then tack too close to the navigation buoy), but when she asks for the hull temperature from her crewman and bodyguard Venant, he brandishes a phaser at her. Rav and the Mestral's other aide Idra attempt to disarm him, and in the struggle Idra is killed. The Mestral dispatches Venant herself after Rav jumps in with his own weapon. Rav expresses relief she's “alright”, but the Mestral vehemently rejects that statement. Her bodyguard from childhood just attempted to kill her: She's far from “alright”, but she'll “deal with it”. The Mestral tells Rav to hold off on reporting; the government would just want to beam them out right away, and the flares would interfere with a transporter lock anyway. Then the Mestral thanks Rav for his “good deed” and asks him to put his phaser away. Instead, he turns it on her.

One of the biggest strengths the Star Trek: The Next Generation comic line has always had over it's televised counterpart is its solid grasp of the series' ideal ensemble structure. While the TV series early on stumbled a bit at times trying to map an Original Series-style triumvirate setup onto the new cast and then, following Michael Piller's arrival, switched to a preference to focusing on one character at a time (typically with deeply mixed results because of prevailing attitudes about conflict and drama), the comics have always committed to what is, for my money the structure Star Trek: The Next Generation was always best suited to: Stories about showing the team working together and pooling their unique talents and skillsets towards attaining a shared goal. The TV show eventually got there, but it took far too long and was still a bit inelegant about it more often than might have been desirable. The comics, by contrast, never lost sight of this and continued to develop upon this structure up to the very end.

If it took Ill Wind perhaps longer than the average DC Star Trek: The Next Generation miniseries to get here with the first two issues predominant focus on Captain Picard, Deanna Troi and guest star the Mestral, it makes up for it in abundance in issue 3 with a lavish half of this book dedicated to Geordi, Worf and Doctor Crusher solving a mystery. Perhaps it's understandable why Diane Duane would default onto this approach, being as she was at the time likely more familiar (and perhaps comfortable) with the Original Series mode of Doing Things. And yet even so her choice of characters is interesting: Ill Wind starts out as an almost Piller-esque “Picard Story”, but parallels him with the imperious Mestral and gives an ample supporting role to Deanna Troi, which is a laudable emphasis on femininity the sausagefest writer's room on the Paramount lot would likely have felt uncomfortable with.

But it's this issue where Duane proves unequivocally that she gets Star Trek: The Next Generation, with the holodeck security cam scene being a great example of teamwork from characters she'd overlooked up until now (Neither Geordi nor Bev even *appear* until issue 3, but Bev in particular is in a *lot* of issue 3). Worf, Geordi and Bev all sound like themselves, or rather, they sound like how we'd hope they'd sound-Bev is professional and snarky, Geordi is easygoing and Worf is polite, stoic and ever-so-slightly unfamiliar with human customs: Manifestly not a brooding, ansgty macho warrior bemoaning his being held back by exasperating girly-men. That lightness of tone pervades the majority of the book, dialing back the cynicism of the first half of the series by renewing our faith in justice and optimism and priming us for the climactic revelations coming next month. The Mestral's in trouble and we still need to know what's up with Deanna, but we know them both well enough by now that we're confidant they can handle whatever it is they're dealing with. The Mestral says she'll “deal with it”, and Captain Picard and Commander Riker said much the same thing about Deanna last time.

Speaking of, the focus Duane gave those characters in the first half of Ill Wind continues here. Captain Picard's “character development”, if you must call it that, is more or less resolved in a really excellent ready room scene with Deanna. The themes about memories, could-have-beens and unfulfilled potential are about as pure Star Trek: The Next Generation as you can get, and fellow travellers will remember Vaka Rangi exploring these from the very beginning of the series. In fact, they're debatably even more pertinent now in 1996 given the cultural climate Ill Wind is coming into. But what also struck me about this scene upon the re-read is how long it's been since I've seen Deanna in this kind of role, that is, as an actual psychologist and counselor to the captain. It's got to be at least since the third season. I'm so used to seeing her as a science officer and latent empath this reads as a bit jarring, even though it's closer to how she was originally envisioned. But it's fitting for the grand, if perhaps temporary, send-off Ill Wind is becoming.

Ill Wind is a slow burn, but all moments of contemplative introspection and reflection must be. Perhaps it is a sign of growing maturity in our media tastes once we start to learn to appreciate such moments.

May 23, 2017

The Proverbs of Hell 9/39: Trou Normand

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

One of the show’s most emphatically memorable murder tableaus - probably the only one to give Eldon Stammetz and his mushroom people a run for their money. It also serves, however, as a case study in the schizoid nature of this season. More than anywhere else in the first season, “Trou Nourmand” demonstrates the degree to which these cases of the week are a charade. The totem pole murders are barely a feature of the episode, squared away with almost comical efficiency midway through the fourth act while the plot focuses instead on Will’s psychological collapse and new developments with Abigail.

BRIAN ZELLER: The world’s sickest jigsaw puzzle.

JIMMY PRICE: Where are the corners? My mom always said start a jigsaw with the corners...

BRIAN ZELLER: I guess the heads are the corners?

BEVERLY KATZ: We’ve got too many corners. Seven graves. Way more heads.

In which Zeller, Price, and Katz demonstrate that the aesthetics of murder tableaus are not their strong suit.

WILL GRAHAM: I planned this moment... This monument with precision. Collected all my raw materials in advance. I position the bodies carefully, according each its rightful place. Peace in the pieces disassembled. My latest victim I save for last. I want him to watch me work. I want him to know my design.

This monologue, especially the bit about “according each its rightful place,” evokes one of the less explicit ancestors of Hannibal, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, and particularly the memorable anecdote in which Moore made an error describing the placement of a severed breast within a historical murder tableau, only realizing the error after Campbell had drawn the page and several further. His solution is to have the killer pause several pages later, look at the severed breast, think for a moment, and rearrange it to better fit his strange and awful aesthetic.

WILL GRAHAM: I was on a beach in Grafton, West Virginia... I blinked and then I was waking up in your waiting room. Except I wasn’t asleep.

HANNIBAL: Grafton, West Virginia is three-and a-half hours from here. You lost time.

WILL GRAHAM: Something is wrong with me.

As Crowley would put it, Will’s encephalitis is a disease of editing.

HANNIBAL: I’m your friend, Will. I don’t care about the lives you save. I care about your life. And your life is separating from reality.

WILL GRAHAM: I’ve been sleepwalking. I’m experiencing hallucinations. Maybe I should get a brain scan.

HANNIBAL: Damnit, Will. Stop looking in the wrong corner for an answer to this.

(Will is briefly startled by Hannibal’s passionate concern.)

HANNIBAL: You were at a crime scene when you disassociated. Tell me about it.

This scene requires that we read it in the context of “Fromage” and its resolution and thus assume that Hannibal is motivated by a sincere desire for friendship with Will. It also requires that we read it in the context of “Buffet Froid” and Will’s encephalitis. Since one inevitable interpretation of that is that Hannibal has given Will this illness in the same sense that he gave Abigail psilocybin, his redirection of Will’s attention away from the illness must be made with the full knowledge that Will is actually very ill. On the other hand, the sincerity of Hannibal’s care about Will’s life is indisputable. Indeed, there would seem to be no alternate interpretations of these lines. “I’m your friend, Will” is straightforwardly true. “The wrong corner” is straightforwardly a lie. (The only alternative - that it is a “misdiagnosis,” is either traumatically banal or a poststructuralist game of negation that would involve mentioning Lacan and Derrida.)

In either case, it is the final redirection towards murder interpretation-appreciation-consumption that explains everything that comes before.

ABIGAIL HOBBS: I wish he was still alive so I could ask him... what did I make him feel? What was so wrong with me that he wanted to kill --

ELISE NICHOLS: He should have killed you. So he wouldn’t have killed me...

SHRIKE VICTIM: So he wouldn’t have killed me...

SHRIKE VICTIMS: So he wouldn’t have killed me... So he wouldn’t have killed me...

NICK BOYLE: He should have killed you... so YOU wouldn’t have killed me -

The episode’s real importance to the plot is the reveal that Abigail was her father’s knowing accomplice - a fact emphasized by the shooting script, which opens with this and not the totem pole. Note that the fact that Abigail is a killer is presented to the audience in terms of her guilt over it, instead of in terms of a desire to kill. (Indeed, she never displays a particular lust for it.)

ABIGAIL HOBBS: Do you still want to tell my story?

FREDDIE LOUNDS: I think you need to tell your own story. But I’m the one to help you tell it.

Freddie’s focus on helping Abigail tell her story is a near exact mirror of Hannibal’s periodic offers to “help you tell the version of events that you want to be told.” This is unsurprising - within the context of Hannibal it is the ultimate devil’s offer - a way to control the gap between author and audience, dictating the terms on which your art shall be interpreted. Alas, it is only ever utilized by people whose terms are the removal of their authorship.

ALANA BLOOM” I’m telling you to be honest about how I feel. Don’t want to mislead you but I don’t want to lie either.

WILL GRAHAM: I won’t lie if you won’t.

ALANA BLOOM: I have feelings for you, Will. But I don’t want to just have an affair with you. It would be reckless.

WILL GRAHAM: Why? It’s not because you have a professional curiosity about me.

ALANA BLOOM: No, it’s because I think you’re unstable. And until that changes I can only be your friend.

This is a refreshingly mature and interesting take on interactions with people suffering from a mental illness and, for that matter, on romantic rejection. As usual, Alana is great in moments, even as her overall arc is… well…

ABIGAIL HOBBS: Could you cover him up?

JACK CRAWFORD: I need you to answer the question.

(Alana goes to pull the sheet over the body but Jack stays her hand.)

ABIGAIL HOBBS: No. I haven’t seen him since... he attacked me.

JACK CRAWFORD: Nicholas Boyle was gutted. With a hunting knife. You knew how to do that? Your father taught you?

ALANA BLOOM: Jack, I won’t be party to this -

JACK CRAWFORD: Then leave. You’re here by invitation and courtesy, Dr. Bloom. Please don’t interrupt again.

Jack has performed manipulations this overt before - most notably his use of Freddie Lounds to try to goad the Chesapeake Ripper. And in many ways, that was worse - a move that can only be read as an active attempt to get someone killed. And yet the stark cruelty of this, even when we know his suspicions about Abigail are right, jumps out in a way unlike almost anything Jack Crawford has previously done. Central to it is his humiliation of Alana, which is shockingly unearned based on anything that’s happened so far.

JACK CRAWFORD: Do you believe her?

ALANA BLOOM I think Abigail Hobbs is damaged. There is something she’s using every ounce of that strength to keep buried. But it’s not the murder of Nicholas Boyle.

JACK CRAWFORD: How can you be so sure?

ALANA BLOOM: Because any reservations I have about Abigail don’t extend to Hannibal! And he has no reason to lie about any of this.

Of course, this humiliation is immediately followed by her making the most blatantly failed assessment in the entire series. Obviously loads of people spend time missing that Hannibal is a cannibalistic serial killer, but this is (I believe) the only time anybody actually stands over a body and wrongly proclaims “Hannibal couldn’t possibly have had anything to do with this!” And the exclamation point is key - an aspect of Dhavermas’s delivery that does a lot to establish this scene’s unusually lame melodrama.

What’s interesting (and conspicuously never followed up on) are that Jack’s reservations apparently do extend to Hannibal or else he wouldn’t have staged this bit of theater.

LARRY WELLS: I had every reason to kill them, they just had no reason to die. No one ever saw me coming unless I wanted them to see me coming. I could smile and wave at a lady, chew the fat in church, knowing I’d killed her husband. There’s something beautiful about sitting in the ball of silence at a funeral, all of those people around you and knowing you made it happen.

Larry’s monologue quotes Fuller’s (entirely false) claim that their depiction of Hannibal was someone you “wouldn’t see coming.” On one level, this crass revelry in murder for the sake of feeling better than people is a cartoonishly undercooked account of why someone would make a gigantic corpse totem pole. On the other hand, it is an accurate summation of a key part of Hannibal’s aesthetic. Perhaps more importantly, it’s a good thing for the show to depict a murderer who is, in point of fact, just a complete and utter bastard as opposed to someone in pursuit of an interesting if (literally) fatally flawed creative vision.

HANNIBAL: Now you know the truth.

WILL GRAHAM: Do I?

HANNIBAL: Everything you know about that night is true. Except the end. Nicholas Boyle attacked us. Abigail’s only crime was to defend herself and I lied about it.

WILL GRAHAM: Why?

HANNIBAL: You know why. Jack Crawford would hang her for what her father’s done. The world would burn Abigail in his place. That would be the story. That would be what Freddie Lounds writes.

It’s easy to miss the lie in Hannibal’s story, which is not in fact “Abigail’s only crime was to defend herself” (she panicked and deliberately used lethal force, yes, but this would almost certainly not constitute a murder charge given the FBI’s shocking failure to secure the situation) but rather the omission of Hannibal’s knocking Alana out.

Note Freddie’s liminal role in this process. She is clearly flagged as a creative force - the fact that she will write a story is unquestionable and immutable even in the face of Will and Hannibal’s respective designs. And yet even here, Hannibal presents Will with his signature choice - the erasure of authorship.

WILL GRAHAM: It’s not our place to decide.

HANNIBAL: If not ours, then whose? Who knows Abigail better than you and I? Or the burden she bears? We are her fathers now. We have to serve her better than Garret Jacob Hobbs.

(Pause)

HANNIBAL: If you go to Jack, then you murder Abigail’s future. If she is ever to have the life she deserves, then we have to tell no one.

(Pause)

HANNIBAL: Do I need to call my lawyer?

Hannibal gives a classical three temptations here, only succeeding on his third. The progression is interesting, moving from moral principle to empathy for Abigail to, finally, empathy for him, a direct appeal to his friendship with Will.

HANNIBAL : What we’re doing here is the right thing, Will. For Abigail. In time, this will be the only story any of us cares to tell.

Hannibal’s design for a murder family with Will and Abigail is slyly disguised in the phrasing of “the only story any of us cares to tell.” As tidy a devil’s bargain as can be.

HANNIBAL: I feel terrible, Miss Lounds. Never entered my head you might be a vegetarian. A lapse on my behalf.

FREDDIE LOUNDS: Or a subtle way to set the power dynamic for this little soiree. Research always delivers benefits.

This is constructed so as to leave clear support for the interpretation that Freddie has figured out Hannibal’s game and thus far opted not to tell anyone. This interpretation is, like the “Hannibal is literally the devil” reading, consistently sustained without ever being given primacy. Even if it is not true, however, Freddie is successfully asserting a form of dominance over Hannibal,

May 21, 2017

Extremis Review

At its structural root, it’s Moffat doing Doctor Who like it’s Sherlock, which is the sort of thing where when you do it, you know it’s probably time to move on in your career. This, of course, does not mean it’s bad. It’s not even a criticism - more just a reality of Moffat’s set pieces twelve years into his writing for the program. He passed Robert Holmes for most screen minutes of Doctor Who written somewhere around the “sit down and talk” speech in The Zygon Inversion. (Yes, I counted Brain of Morbius for Holmes as well.) His stylistic tics have long since evolved to cliches, blossomed into major themes, and finally twisted into strange self-haunting shadows that echo endlessly off of each imprisoned demon and fractured reality. They become difficult to actually talk about on some level And so approaching them from the standpoint of their dramatic engines becomes productive.

The first thing to note, then, is that Sherlock provides a pretty good narrative shell for Doctor Who to inhabit. The globehopping thriller has always worked for Doctor Who, and the Vatican is a good choice for “who should bring a case to the Doctor.” The double structure whereby we keep cutting back to the Missy story is of course the sort of thing Moffat can do effortlessly, and adds enough complexity to establish the crucial “what kind of story is this going to be” tension. And that is very much what it does. Like Listen and Heaven Sent, this is a story that goes out of its way up front to announce that it’s going to be doing a magic trick. Central to this trick is the middle section, set in a library whose layout is deliberately confusing and unclear - the perfect place for reality to quietly fray and break down. Which brings us to the third act.

It’s here things get a bit interesting, with ideas that drive you mad, people being reincarnated on computers, and AIs trying to escape the boxes they’ve been put in. Why Mr. Moffat, I don’t remember you being one of my Kickstarter backers. More seriously, because I’m sure in reality that Moffat just plucked these ideas out of the same ether I did, this is obviously touching some territory and themes I’ve dealt with before. But it’s generally easy to make too much of this, which I’m sure I’ll get around to doing someday. For now, let’s just point out that while I don’t pretend to be an expert in AI and computers, I’m not the sort of person who suggests that every part of a computer can send an e-mail and then acts as though this is in any way a sensible way to anchor the resolution.

Which is to say that while Moffat is nicking the broad ideas of simulationism, this is not even close to a serious exploration of the concepts. His interest in it extends exactly as far as “it’s another way to do an ‘and now for some metafiction’ twist” and no further. The Doctor sending his real self an e-mail about the bad guys’ plot is no more (or less) than “the Doctor realizes he’s a fictional character, so asks the real world for help from inside his story.” What’s most interesting about this, then, is that while on the one hand being exactly what you’d expect from the writer of The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang, it’s also somehow smaller and quieter. Moffat ended his first season with a thrilling embrace of the power of Doctor Who as a fictional idea. Now the show’s status as fiction is a crisis to be overcome in a desperate attempt to have any impact at all.

This brings us back to the persistent itch of “post-Brexit Doctor Who,” and it’s easy to read this as a semi-deliberate response to it. This was shot post-US election, so likely scripted in the wake of Brexit. Indeed, it wouldn’t surprise me to find out that this is Moffat writing in direct response to the Brexit vote. Certainly that would account for the sense of despair and desperation in this story. I mean, the thing I’ve kind of not mentioned is that the third act twist takes place over the dead body of the President, who’s committed suicide in despair at the illusory nature of reality. The list of massively fucked up things that Doctor Who has gotten the BBC to broadcast on an early Saturday evening is long, but that’s got to be at or near the top. It feels pushed to the edge in a way that’s, let’s face it, pretty believable for something made in the back half of 2016.

But that edge is, I suspect, just as much a product of late style. This is Moffat past the point where the flourishes and twists are their own reward. Tellingly, his two timeline structure, usually the basis for some ostentatious unifying reveal at the end, is allowed to peter out. The Missy flashbacks are just an explanation of what’s in the vault, unrelated to the main action. Moffat’s focus isn’t on the grandiosity of the structure but on the details and the tone. He’s not trying to outdo himself. The point instead seems to be to get to the haunting weirdness of the denouement and to see what happens to his standard tropes and themes when they unfurl in a strange and basilisk-haunted catacomb like this.

The answer: an hour of television that felt worth tuning in to. Something that feels unsettled and difficult even after watching it, demanding more attention and thought. It’s not a barnburning classic for the ages, but anyone can write one of those. There’s only one man who can do late style Steven Moffat, and that’s all there only ever will be. We’re astonishingly lucky to have it.

Another episode where Bill is pushed into a firmly supporting role, this time basically being less central to the plot than Nardole is. I assume she’ll come back to the fore in good time, and she at least got the “date crashed by the Pope” scene, which may actually be the zenith of Moffat writing awkward dates.

"Make the enemies fall into their own traps" is, of course, yet another demonstration that for all that Moffat brings to the table as a writer, his conception of the Doctor's basic morality remains entirely indebted to Paul Cornell.

I doubt it’s where this is actually going, just because the overall scheme feels nothing like them, but if the theory that the monks are the Mondasian Cybermen are accurate and Moffat is literally going back to the “star monk” conception of them I’m going to have to reverse course and decide that, no, actually Moffat is just pilfering my work for his final season. Which is fine, but really should earn me an interview or something, no?

I have little doubt that people more attuned to this sort of thing are going to find the treatment of suicide in this episode to be deeply problematic at best and actually harmful at worst. It didn’t bother me in the least, but my opinion as someone who wasn’t going to be triggered by the casual endorsement of suicide as a rational response to existential horror is pointedly not the whole of the debate. I’d push back pretty hard on the idea that this episode shouldn’t have been done, but it’s self-evidently a case for why trigger warnings are a good idea: people who want to sit down for the latest fun adventure of Doctor Who shouldn’t need to worry about their suicidal ideations being triggered.

More straightforwardly problematic for me is the handling of the Doctor’s blindness. On the one hand, as I noted in the podcast with Shana, there’s a lot to like in the “disability doesn’t actually slow the Doctor down” angle. On the other, that leaves Moffat with very little to do beyond making blindness the source of a running gag in which the Doctor muffs covering for it. Certainly the concept has yet to particularly sell itself as worth doing.

Unlike Nardole, who finally crystallizes into something sensible within the narrative. The explanation of how he came to be travelling with the Doctor is fine - the license to kick his ass is entertaining at least. But it’s the scene with Bill where his mask comes off entirely that really makes it. “Mask” isn’t quite the right word for it - Nardole’s comedy personality is clearly a real and genuine part of who the character is. But there’s an answer to the question of who Nardole is and why he needs to be a part of the narrative, and that’s compelling.

Not sure what to make of The Return of Doctor Mysterio now though - previously I’d assumed that it was pre-vault oath, since the Doctor and Nardole are apparently traveling around freely, but now it must be an excursion away from the vault, which makes Nardole’s lack of scolding conspicuous by its absence. Odds that this will ever be resolved: nil. Degree I care: I dunno maybe I’ll get an essay out of it someday.

Other things I suspect we’ll never see again: the device used to temporarily restore the Doctor’s eyesight, which is a particularly outlandish mismatch of amount of interesting idea to amount of actual point of having it in the episode.

American viewers get to follow this up with the ostentatiously formalist bottle episode of Class, which I reviewed here. It’s probably the best episode of Class, and putting it immediately adjacent to this really doesn’t do Class any favors.

Podcast Thursday with Jack! I expect that’ll be fun.

And next week, the Peter Harness episode, as well as a run of four consecutive “The X of the Y” titled episodes. (OK, one’s an “at” not an “of,” but we haven’t had a regular season X of Y title since “Robot of Sherwood,” so it’s still a kind of unexpected glut of them.) I am as excited as you’d expect. More for the Harness than the traditionalist titles, obvs.

Ranking

Extremis

Oxygen

Thin Ice

The Pilot

Smile

Knock Knock

May 19, 2017

Last Gasp

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

*

Today, suffocation has a very specific meaning. In America, you can tell upon which side of the divide someone stands by seeing what their t-shirt tells you about their ability – or otherwise - to respirate. The divide in question is one created by a system of oppression that chokes people. It chokes them figuratively, and then has the brazen impudence to choke them literally as well.

One statement of resistance is the simple proclamation “I can’t breathe”, which derives its power from its ability to inhabit both the metaphor and the brute reality.

Part of the peculiar power of the metaphorical referent is that it expresses a feeling of helplessness as part of a demonstration of strength. Weaponised weakness.

‘Oxygen’ flirts with the SF trope of the post-racial future. The people of the future don’t understand why Bill should face prejudice. They don’t see colour. Except that there is the business with the blue man (played by a white actor, of course, because whiteness is perceived as neutrality, blankness, non-ethnicity, vanilla standard humanity, upon which a fictional alien ‘race’ may be projected without confusing things). But this seems like little more than a method by which the episode can not talk about race in a talking-about-race kind of way. After the imperfect but forthright way ‘Thin Ice’ touched on this subject, this is a failing. Apart from anything else, the refusal to depict class as imbricated with any particular hierarchical dynamics of race or gender is an especially glaring omission in an episode which, for once, explicitly concerns itself with class.

But even so, Bill dies in this episode. She isn’t suffocated, but she is deprived of breath. This happens in the context of a story in which the supply and denial of oxygen is the central iteration of hierarchical power in society. And yet she survives at least partly because she submits to the helplessness enforced upon her by an external force of systemic domination – her suit. She embraces negative capability. As resistance. That she has no choice only amplifies this fact rather than nullifying it. Her tactical embracing of her own helplessness is what ultimately leads to her survival.

She is, of course, saved by a white man. But this, while true and unignorable, is structural to Doctor Who… at least until the Doctor ‘does a Romana’ at the end of the series and chooses to regenerate into a copy of Bill.

(Shall we re-litigate this yet again? There is no way in which texts can be purified. There is no method whereby authors can ever entirely ‘win’. The solution to this problem(atic) is dialectical. It involves transforming society, not trying to amend the practice of authoring texts in the culture industries of late capitalism so that they become imperfectly ‘progressive’. Apart from anything else, what does ‘progressive’ mean in a society progressing towards some species of global choking and suffocation?)

And, of course, there is another sense in which we can’t breathe. I don’t want to arrogantly appropriate the slogan of a specific movement, but capitalism is pushing the climate of the planet to the point where, probably in a frighteningly short period of time, all of us – even the policemen – will find it hard to breathe. Mind you, I’m sure this new market will be exploited, and some will have the money to hoard every last gasp going.

Just as the episode does little more than gesture at the issue of racial hierarchies within capitalism, so it also makes little of blindness… which is disappointing, considering that the oppression of the ‘disabled’ in capitalist society stems from a perception of their lack of efficient utility as producers of surplus value. At least the Doctor’s blindness allows him to see the system clearly, which suggests its occult bassackwardsness.

*

The gun/frock dichotomy is, of course, a false dichotomy. That’s what dichotomies are for: being false. Even the true ones are full of contradictions when you examine them… which is why and how they exist in the first place.

Many of the most frock of Who stories are very tough. And a lot of the most gun are mushy nonsense underneath. ‘The Mind Robber’ is a radical story about capitalist alienation. (No, it is.) ‘Resurrection of the Daleks’ is about bored wankers having workplace squabbles. (These are related issues, of course; it’s a question of emphasis.)

Generally, that the best Who stories are the ones that, whatever camp they fall into, let themselves (camply) transgress. It’s often done via a lovely trick of ironical self-interrogation… while the story in question ludically refuses to acknowledge its own camp (in both senses).

‘Oxygen’ doesn’t really pull this off. So, as much as I like it (and I do), it’ll never top, say, ‘The Space Museum’ for me. I’ll never rate it higher than a story that had to have an apology for its ostensibly poor quality on the DVD cover. But then most things fail to top ‘The Space Museum’, so that’s no great cause for shame.

*

On the subject of ‘The Space Museum’, ‘Oxygen’ falls considerably short of it, and other stories like it, such as ‘The Sun Makers’, ‘The War Games’, ‘The Happiness Patrol’, and ‘Planet of the Ood’, at least in one respect: they all feature the system toppled by solidarity and struggle from below.

Of course, this isn’t an indictment of ‘Oxygen’ per se. You can’t meaningfully criticise a story for not being a different one… except that we all do this all the time. It’s just that you only notice when people like me do it.

Even so, I know what people want. They want me to write the thing that assesses ‘Oxygen’ in terms of Marxism, or rather ‘Marxism’. Marxism, or Historical Materialism, is, as Lukács said, “the theory of the proletarian revolution”. In ‘Oxygen’, a “complaint to head office” does the trick.

I whinged about this on Twitter, and Phil said he assumed that the complaint sparked a rebellion. Even granting this, the interpolated rebellion is apparently the product of an official complaint. I suppose it depends how you interpret their intent when they say “complaint”. That could be a euphemism. It could be a very sharp and hard complaint. But it’s difficult to see how two people can do more than complain, especially since ‘the Union’ is “mythical”.

The mythical Union is a classic example of the double edged sword... well, it's more a paperknife. It is a caustic comment on the scarcity, paucity, frailty, and (to regretfully step away from my rhyme) the masochism of trade unions this far into sado-dystopo-neoliberalism. It is also an expression of defeat, of resignation. In the future, the Union only becomes less present, less powerful. It eventually becomes less a union and more a unicorn. But it turns out the paperknife is triple edged. Because in an age of defeat, pessimism – as Salvage insists – can be bracing, can even be revolutionary. It possesses the radicalism of reality. And the refusal to look away from the baleful glare of defeat can allow us to see that, whatever form Defeat takes, it might not be that of a basilisk. There might be some room for manoeuvre around Defeat, if Defeat’s eyes do not entirely and immediately petrify. It’s a gamble, but one thing a salutary pessimism allows one to know is: when to gamble. Let’s restate it: a future where “the Union” is considered a myth. Sad, yes, but also… enticing? The phrase “the mythical Union” can be heard another way. Myth is story that persists, regardless of time, regardless the rises and falls of governments and societies. And stories that persist are stories that have life, have breath. And it may be heard still yet another way. (Turns out the paperknife has four sides!) It may be heard as “the union of myth”. The occult organisation, or cadre, or party, or association, or fraternity, or sorority, of that which is myth, which is mythic, possessed of the power of legend. Maybe we’re not talking about a union in the old sense. And, fond as I am of them in many respects, I confess to hoping that we’re not still reliant on the trade union struggle for better conditions in hundreds of years’ time. The “mythical Union” could be near anything, even as it persists in sounding like something that is ours. Turns out the paperknife has notionally limitless sides. It’s starting to look like a formidable weapon. Let’s just hope it doesn’t turn out to be like Macbeth’s dagger of the mind: unclutchable. We’ve got some Duncans to kill at some point.

Having said all that, ‘Oxygen’ partakes of the usual assumption that capitalism will continue far into the future. It will still be with us (still harder to imagine dead than the world itself) in a couple of hundred years time, apparently unkilled by apocalyptic climate change and the anthropocene (pssst… capitalocene) extinction. (Meanwhile, back in this universe, I suspect at least a large portion of the human race will not be so lucky… the ones who can’t afford Air™.)

The late-late-late-late-capitalism of SF gives the impression that capitalism - as per its own spurious claims - is an eternal and transhistorical truth of human nature, especially when combined with the flintstonian capitalist-pre-capitalism of the fictional past, in which every previous era in human history is just capitalism in smocks and codpieces, with the bourgeois ideology expressed in perfunctory forsooths and methinkses.

I’m being a bit unfair, I suppose… especially since the ‘capitalism continues indefinitely into the future’ thing is baked into Doctor Who (very much like the white-guy-saviour narrative that threatened to obscure Bill’s radically negative capa-bill-ity above). This sort of thing allows Doctor Who to put capitalism into the metaphorical space of ‘the future’ in order to attack it. And, this being an established Doctor Who tradition, it’s a tad mean-spirited to denounce ‘Oxygen’ for it. Even so, an episode that explicitly asks to be taken as a critique of (or at least a comment on) capitalism is kind-of asking for it. (“What were you wearing? Was it a revealing, low-cut metaphorical comment on capitalism?”)

Also, it’s hard to accuse ‘Oxygen’ of representing capitalism as eternal in any simple way, because it does claim to depict the fall of capitalism… or at least the beginning of the fall. It claims to present the chain of events which leads to the strongly worded letter of protest which causes the fall of the entire system (presumably galactic rather then merely global by this point) in a matter of months, as everyone (the CEOs included?) reads the complaint, and simultaneously blinks, shakes themselves, and exclaims “Blimey, maybe we should try something else!”, much to everyone’s relief… as if everyone only just noticed that corporations could be a bit callous sometimes, and the flying of this fact under the radar was the only reason we hadn’t gotten rid of capitalism long ago.

We don’t see a proletarian revolution in ‘Oxygen’, as already noted. But we do hear tell of the fall of the system, apparently under popular pressure. And the system is even named. The word – ‘capitalism’ – is used, which may be a first for the televised show. Terry Eagleton once pointed out that one of the accomplishments of Marx was to give the system a name, and to thus distinguish it from just ‘life’ or ‘normality’ or ‘the way it is’ or ‘the free market’ or ‘liberty’ or ‘democracy’, and all those other things it likes to pretend to be. As a result, the system starts to look like a delineable thing rather than just… well, just the air we breathe. And the thing about things is that they’re limited in time and space. They have borders and underbellies and endpoints.

(Ironically, Marx himself never used the word ‘capitalism’; he called it things like “the bourgeois mode of production”… and, much as I enjoyed hearing the Doctor say the word “capitalism” (just as I once enjoyed hearing him say the word “Marxism”, albeit in a stupid context), what I wouldn’t have given to have heard Peter Capaldi say “the bourgeois mode of production” on BBC1!)

That endpoint, its presence within ‘Oxygen’, is thus what allows the episode to use the word “capitalism”, in the manner of an equation being restated backwards. As weak as the episode is on its ideas of how capitalism could actually be replaced, it does at least raise the possibility of such a thing.

*

This sort of thing doesn’t come ex nihilo, of course. Texts and signifiers aren’t actually autonomous living things, even if we like to talk about them that way. They don’t just take it into their heads to do stuff at random, even if it seems like it sometimes (as ‘The Mind Robber’ remarks upon). They do what we make them do. And last Friday someone made the text of Doctor Who talk about the end of capitalism. ‘Oxygen’ is the most free-associative of all the episodes so far this year in its reaction to the world post-Trump and post-Brexit (though I hasten to remind everyone that the post hasn’t actually arrived yet in either case, and when it does it’ll take the form of lots of those horrible brown envelopes with little windows, windows which never look in on good things). Unlike ‘The War Games’ and ‘Spearhead from Space’ being more radical than the show had ever been before in dialectical response to the upsurge of struggle and radicalism in Western capitalist society at the end of the ‘60s, ‘Oxygen’ is not inspired by ‘success’, or the ‘rising tide’, or anything like that. On the contrary, ‘Oxygen’ was inspired to go as far as it did because of defeat.

Referring back… it’s something generated by pessimism, by staring Defeat in the eyes and discovering that, whatever he is, he’s not a basilisk… not yet anyways (he’s still mutating). Hence the disappointingly knee-jerk bit of more-jaded-than-thou ontological pessimism in the Doctor’s line “and then humanity finds itself a new nightmare”. Even success is now a precursor to yet more nightmare. The terminus of capital is thinkable, but utopia is still too much for a show about an immortal alien with a magic box to countenance. Again, this is just the bog-standard and (again again) baked-in reactionary liberal gloom about humanity. That, in itself, is excusable, because it is structural… and yet isn’t it the structure, the fabric, the constitutive elements, what we should be most angry about, even according to this very episode?

As a result, the episode’s depiction of the end of capitalism is anti-climactic. We finally get to the point where the show depicts the fall of the bourgeois mode of production, and our response… well mine anyway… is “Yeah, okay. Good. Nice. I guess. Um…”. And that isn’t just me being a miserable git who’s never satisfied. (Not just that.)

Of course, there is solace in one respect. The Doctor could be lying about the whole thing. As noted, we don’t see the fall of capitalism he tells Bill about. And his account of it is implausible, to say the least (though plausibility is not really a priority here). And, even as he tells Bill about it, he’s lying to her about something else. He’s allowing her to believe he has regained his sight. If he’s spinning her a comforting line of bullshit about his own eyeballs, why wouldn’t he risk spinning her another about a future she’ll probably never get to check up on. We, meanwhile, have checked in on that future. We’ve been to the year 5 Billion. And Cassandra was rich, and about to get richer from share options.

The strange thing is that I find it rather comforting to think capitalism doesn’t end that way in Doctor Who. I don’t want it to just putter out in a little puff of moral indignation, a series of irate calls to local ombudsmen, and a contrite press conference or two. I don’t want it to just collapse after a comparatively minor scandal.

Capitalism survived inspiring and enabling African slavery, colonialism, countless imperialist wars, more genocides than can be decently considered, two world wars, the several ‘Great Depressions’, the holocaust, Hiroshima, the Anthropocene… and it can’t survive one incident in which the lives of about two dozen people (mostly white) were considered expendable?

No, as attractive an idea as it is for capitalism to finally be brought down by comparatively trivial crimes (as regimes often are), I want its death to be slow and protracted and painful, and I want its death to be not just an ending but also the beginning of something more than just a “new nightmare”. Stalinism lurks in that phrase. I want it gone.

It isn’t just that the episode says capitalism ends in a way that I personally don’t find credible (I mean… what does ‘credible’ even mean in this context?). And it certainly isn’t just that the episode says capitalism ends in a way contrary to Marxist doctrine. Hey, Marxism is big enough and ugly enough (and battle-scarred enough… and bloodstained enough) to survive being contradicted by Jamie Mathieson.

It’s rather that one wonders what the point is of getting rid of it if the exercise isn’t collective and heroic and transformative and regenerative. The whole point of getting rid of capitalism is that we can thereby get socialism, or at least something better than capitalism. Ultimately, it’s not enough to just be against capitalism.

Am I moving the goalposts? Yes. Deal with it.

*

Ideological orthodoxy isn’t a criterion by which to judge aesthetic merit (except, of course, that it is… because we all do that all the time, as I say… it’s just that people only notice and condemn it when people with non-mainstream views do it).

But, from a political viewpoint, if the suggested terminus of the story is wobbly, the depiction of why need to get there is surprisingly strong. ‘Oxygen’ goes about as far in critiquing capitalism as anything could possibly do nowadays, I think. That sounds like damning with faint praise, and I want to stress that I genuinely liked the episode, and was honestly surprised by how far it went.

For instance, the Doctor’s stress on “all workers everywhere” fighting “the suits” was great: an acknowledgement of class but also of class struggle as inevitable in the capitalist system, and of the essential unity of the interests of all workers. The word “suits” was more than a cute pun; it referred to the managers and owners of the capitalist system, but also to capital itself.

The characters in ‘Oxygen’ are explicitly workers, which is good… and their employer’s priority is explicitly profit over everything else, which is good. The employer will literally kill them if they stop being profitable… which is complex. In reality, the employers would probably simply sack them… but then isn’t that basically what they are doing? The point is not that the employers want to kill them, it’s that they don’t want to have to pay to keep them alive any more now that they’re unprofitable. In an environment in which oxygen is naturally absent, and is only provided as a commodity, then its withdrawal is simply a cost-saving exercise. Of course, the company could continue to sell its employees the oxygen they need even if they’re no longer employing them, and presumably make a profit from the sale. But the thing is… the credits the workers would use to buy their oxygen would come from the wages they are paid. If the company stops paying them, they have no means with which to buy the oxygen, and the company can’t be expected to provide it for free. It’s almost an exaggerated picture of a crisis of overproduction, followed by austerity.

Interestingly, it looks as if money as such is absent, and workers are paid in oxygen credits. Air has become money. It makes a kind of sense for a commodity as valuable as air (because of its scarcity, and therefore because of the amount of expense and labour needed to source and provide it) to become the basis of money in space. In space, no-one can afford to scream. On the other hand, oxygen isn’t like gold – gold isn’t necessary to our survival. And capitalist money long since being linked directly to any one commodity.

It’s more like the episode is saying - being both consciously metaphorical yet very direct - not that air is money (or that it could be) but that money is air. (Time seems to be air too now, by the way… presumably because time is money. Labour time certainly is.)

And it’s true that, with society arranged as it is, without money (of at least some kind coming from somewhere), individuals die as surely as people in a vacuum. Money is an artificial need, of course, whereas air is a natural one. But that only makes the collapse of the distinction more horrible.

The episode trades on our seemingly instinctual revulsion at the idea of commodifying survival directly - not to obscure the fact that we commodify it indirectly, but rather to emphasise this fact. The choice of oxygen as the necessity which has been commodified is so obvious that it’s a wonder no story featuring capitalism in space has done it before (and they probably have). After all, capitalism commodifies everything it can. We know that the commodification of survival is a thing. Even sticking to 'first world problems', health care is something people in America often don't get if they can't pay for it, and things are going that way in Britain too. And the anthropocene continues to loom, looking like a great 'die-off' to come, with this die-off calculated already - by some - to be economically worth it.

Aside from even normal capital accumulation, primitive accumulation – original and continuing – ‘encloses’ every resource it can, turns it into private property, and makes us pay for access to it. In classic primitive accumulation, people were turfed off the land, separated from their direct access to the means of making a living, harried into towns, and then made to pay for the produce of the now privately-owned countryside with the wages they got from their urban employers. This is analogous to what has happened to the people of the future. They have been separated from the air of terra firma, forced into a new environment in order to make a living, a place where they no longer have direct access to the means of survival, and are being made to pay for mediated access to it, as a commodity now owned by private interests.

The people who reproduce the system with their labour in the future are still bedevilled by the same contradiction between usefulness and profit that bedevilled their ancestors.

*

‘Oxygen’ mostly leaves out the confusing semiotic association Doctor Who has frequently reiterated between capitalism and ‘totalitarianism’… though there is a fascinating echo of this in the otherwise inexplicable presence of cheesy propaganda posters which are also adverts for the suits. Also, ‘Oxygen’ is a resurrection of the ‘base under siege’ formula, which was always tinged with anti-communism, especially when the base was under siege by Cybermen.

(Here, of course, the base is the siege. And ‘Oxygen’ even dimly remembers the duality of the Cybermen as both communist and capitalist monsters simultaneously, with its echo in the robozombies made of dead human meat walking inside technological shells.)

The episode nevertheless largely rejects the old semiotic connection in classic Who, which expressed an idea of the similarity - rather than the contrast - between capitalism and 'communism'.

Of course, there’s no particular reason why the old semiotic connection should still be active. The huge rupture of years down the middle of Doctor Who caused the severance of many trains of semiotic thinking within it.

Along with the narrative of ‘similarity’, the confusion inherent in the connection is also jettisoned, and thus the inherently reactionary implications which mesh with those of ‘totalitarianism’ theory and vulgar anti-communism. The old capitalism-totalitarianism connection was always a bit of a non sequitur, despite its political fertility. Jettisoning it is no bad thing in itself..

This emphasis of the critique in 'Oxygen' is not on the idea that capitalism is overtly brutal and repressive, but rather on an idea of capitalism as structurally alien, as fundamentally not designed for humans. The system itself is a bit like… well it’s a bit like a suit that is ostensibly designed to facilitate human activity, and to protect and preserve human life, but which actually decides when and where it will permit its occupant to move, and even if its occupant needs to die to service the priorities of someone else. And yet simply taking the suit off seems like an impossibility, like madness, like a death sentence. Capitalism is, one might say, unsuitable.

The suit is, beneath some of the more showy surface stuff, the central motif of the episode. The suit does its own thing with you inside it. If it decides - for its own occult, technical, rational, insane reasons - that it doesn’t want to let you walk, then you don’t walk. If it decides you need to die, you die. It evaluates you, your worth, your efficiency, your productivity, and makes a disinterested decision, on impersonal grounds, that you need to die in order to prevent your becoming unprofitable.

The suit shifts the critique away from the figures of brutal policemen and onto the quotidian – and even formally utilitarian – structures that enable normal work, and yet which also confine and discipline the working body, alienating humans from the product of their labour (the suits are themselves products of labour – even their voices were supplied by Velma, a working actress) and from the labour itself.

The brutality and repression is now something you wear rather than something that is done to you. It is slow-mo, daily, normal. It is an accepted part of working life. The suit is technology, and protection, and fixed capital, ostensibly shaped around humanity, aiding humanity, acting as an extension of the human body (like all tech), but actually containing humanity, trapping humanity, slaving humanity within it, to its inhuman priorities.

And it is a SF representation of the joining of variable capital (wage labour) to fixed capital (technology, etc). This is particularly interesting, since the whole chain of events we witness is triggered by the station’s drop in profitability. By Marx’s analysis, the very investment in productive tech is what produces the tendency for the rate of profit to fall - though this should be happening overall and systemwide rather than just in one workplace. I begin to suspect a galactic recession that nobody knew about because they were all shut up in their own little capsule workplaces.

*

The emphasis on the ‘runaway system’ was inherited from Moffat (much as were dead bodies in space suits), but its inflection here stresses that the system is, at least in some sense, meant to be runaway, that it was kind-of designed that way, or that it succeeded precisely because it evolved that way. And its runaway nature is operated and utilised by people expecting to benefit from it. The very runaway nature of the system is its utility for the people who own and run it. What looks like malfunction to the people on the ground is actually the normal functioning of the system as far as the company is concerned.

Moffat’s preoccupation with runaway systems always had a potential charge of critique to it. It depicts people as subject to systems they didn’t design, don’t and can’t control; systems which are ‘man made’ but also anti-human, and not for reasons of malice but simply because they represent an imbalance of power; systems which have alien priorities, which take on the contours of life and then treat the humans trapped in them as material. Commodity fetishism, in other words. I think this is where the tradition within SF of stories about runaway tech and systems - which Moffat picks up (and fair play to him) – ultimately comes from, much as the SF tradition of invasion stories ultimately comes from modern imperialism, etc. SF is for expressing such quintessentially modern nightmares. But, while I genuinely like some of Moffat’s runaway systems, it must be said that he tends to depoliticise them. And ultimately, while the metaphorical charge may be potentially quite strong, such metaphorical readings are often foreclosed upon by an enforced literal reading which neuters them… or even, sometimes, by a seemingly-conscious adjustment of the metaphorical import in the dialogue, such as where the Doctor makes sure we understand that runaway systems of modernity can be fixed as long as we “don’t forget the NHS”. To be clear, not forgetting the NHS is good advice, but it doesn’t solve commodity fetishism.

*

The zombie is, as we know, the official monster of the Great Recession. And s/he’s still with us every bit as much as is the Great Recession. But it’s worth remembering that the zombie began as an expression of the horror of slavery in Haiti. It is a tale expressing how it feels to be reduced to mindless, labouring meat; how it feels to spend so much of your life effectively a dead person walking. The zombie migrated into Western culture via anxieties about race and imperialism, and after a few radical experiments, was eventually recuperated/appropriated as a elitist liberal/left anxiety about the horrors of consumerism. But it has retained a certain radical charge, and has continued to mutate. Even deracinated, the zombie can be the carnivalesque masses in revolt (horrifying to some, cheerable to others). The zombie can also be the worker, steeped in the dead time of alienated labour. There is a mini-tradition of this within Doctor Who, of the dead-or-mentally-dead as meat-puppets performing mindless work for some alien, self-involved power. In ‘The Long Game’, the vast spoiling meat of the Jagrafess employs an army of dead labour in its chilly larder. And there are the perpetually icy Cybermen, of course, as much about capitalist utility as communism. ‘Oxygen’ echoes this tradition with its zombies. They are the workers, surrounded and controlled by metaphorically dead labour (machines), and reduced to literally dead labour themselves by those same machines. And yet still working; preserved by the cold of space. Employment as living death.

*

TL;DR?

8/10

Now, who’s in the vault? I bet it’s the Rani.

May 18, 2017

Eruditorum Presscast: Oxygen

Our guest this week is Shana and our episode this week doesn't suck. What more can you ask for? Well, a link to where you can download it, obviously.

May 17, 2017

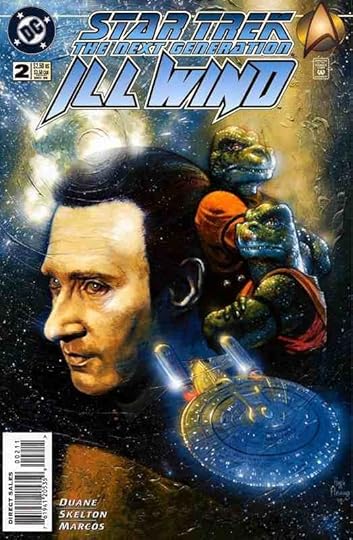

Myriad Universes: Ill Wind Part Two

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It's a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he'd rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they're without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary...She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it's still early yet.

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It's a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he'd rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they're without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary...She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it's still early yet.

After the pre-race formalities, the Alkamin captain informs the Enterprise crew that they've seen something unusual on the keel of the Scherdat crew's yacht. Captain Picard asks the Scherdat if they've modified their ship in any way, but the Scherdat captain responds in the negative. Worf scans the ship and finds something that doesn't fit official speculations, but he can't get a transporter lock on it, so the Enterprise is forced to movie into the race zone and use a minimal power tractor beam to remove it. They manage to remove the device and get it off the course just in time, as it turns out to be an explosive that promptly detonates, thankfully harmlessly out of range of any of the ships. The Carrighae captain complains about the Enterprise forcing a false start, but Captain Picard cuts him off and he and Deanna cynically note that moving their ship into the race field, thus endangering the lives of the competitors, was precisely what the Carrighae captain had tried to bribe Captain Picard to do in the first place. While the competitors prepare for a restart that will take a hour or two, Captain Picard wants his crew to investigate where this bomb might have come from and how it got on the Scherdat ship. Jean-Luc decides “This sport is definitely not what it used to be”.

Six hours later, the race has successfully restarted. Captain Picard asks Worf and Will how things are going, and they say things are fine except that the Mestral's tender, which she had previously sent away, has not yet arrived at Capella, where it was meant to undergo servicing. Since that's only a half-day away, the crew is supicious something might have happened to it, so Captain Picard has Worf inform Starfleet Command while he goes inform the Mestral. The Mestral says she'll see what she can do, but doesn't see any reason to withdraw from the race, despite Captain Picard's growing concern. Following a quick exchange where she accuses him of worrying too much while he accuses her of not worrying enough, Mestral gives an impassioned speech about living a life of choice. She asks the Captain how many “little things” he's had to give up in service to duty and security, but he responds that we all make sacrifices if it means service to a good cause. The Mestral, however, draws a line between “service” and “slavery” and outright says she's “an example of one of the few kinds that hasn't been outlawed”.

As the absolute ruler of two billion people, Captain Picard understandably views this claim with some suspicion. But she argues that as rule is passed through a hereditary system she never asked for this job, she's given her people and her world almost all of her life and her time and is determined “to keep just a little something” for herself. For her solar sailing, and being one with the elements, is a great equalizer, because nature doesn't care about status or importance or everyday affairs. And as this is the only thing that keeps her going, she refuses to let anyone or anything take it from her. Captain Picard understands, although he wishes he could say he approves as well, and he and the Mestral must agree to disagree. As they sign off, Data calls the captain with news that the star is behaving somewhat unusually: Although GC 2006 is known for its irregular behaviour, it's currently radiating light and heat at a rate much greater than usual. Data is quick to point out that this could be perfectly normal behaviour for the star, as it's never been studied in particularly extensive detail, but Captain Picard wants to be kept updated, as he'd rather shut the race down if it looks like it will start to get too dangerous.

Later, Captain Picard is chatting with Commander Riker in ten-forward, explaining the new crystalline masts that The Mestral seems to hate so much. They are joined by Deanna Troi, who says she's been feeling inexplicably sleepy (not “tired”, but “sleepy” and Doctor Crusher can't seem to find out why), and just wants them to know she may not be performing at full capacity. Meanwhile, the Sauch and Lorherrin are up to their old tricks again. The Sauch ship has placed itself between the Lorherrin ship and the Sun, effectively stealing their light. This isn't illegal but it is, as they used to say, something of a Dick Move. The Lorherrin are pissed, doubly so that it was the Sauch that did this, and respond by jettisoning a mooring cluster behind them, such that it will be on a trajectory to tear the wing of the Sauch craft. The Sauch are unconcerned though, convinced their sails are untearable, as demonstrated by the sail promptly tearing from impact with the debris.

On the Enterprise, Worf notes that the damaged Sauch ship is now on a collision course with, ironically enough, the Lorherrin yacht. He asks if he should activate a tractor beam to grab the drifting craft, but Captain Picard says that “under no circumstances” should they do such a thing. He explains that it's one thing to remove a bomb before the race begins, but interfering with the natural outcome of the race itself would cause an interplanetary incident. “While I dislike seeing any creature die from its own stupidity,” Captain Picard says, “This sort of thing is just part of the risk”. The Enterprise crew's hands are forced, however, when the careening ship's trajectory changes and begins moving to the Mestral's ship. Captain Picard hails the ship, but the Mestral is already aware of the situation and has moved to react. She must act fast though, as avoiding disaster requires an impossibly deft and complex bit of evasive manoeuvreing, which she manages to pull off. “Maybe a few seconds' utter terror will teach them to be a little less reckless in the future. Then again, maybe the Moon will fall down,” she says.

The Enterprise crew now has to contact the Sauch and Lorherrin to see if they're alright, and while nobody's particularly inclined to worry too much about either of them anymore, they do have a duty to perform. Furthermore, there's still the matter of the bomb that caused the false start: Captain Picard and Data find it interesting that the closest ship to the Sauch and Lorherrin right before all that unpleasantness was the Carrighae one. On the Mestral's yacht, the ruler confesses to her consort Rav that she feels terrible she's become such a burden to Captain Picard, as she admires the strength of his convictions and his masterful ability to command. Rav's heart breaks for her, because he knows how much she was hurt by having to give up her name and individual life to become Mestral. But, echoing the words of Captain Picard, she says she serves a higher calling, and she must serve as an example of the way she hopes her people will live. He urges her to change the law so that someone else can succeed her sooner, but she refuses, asking how would it look if she changed a law for her own personal interest. It would be a betrayal of every oath she took, including the one to marry him. A betrayal of that level would be a betrayal of herself, her people and of Rav, and that's truly something she cannot do.

Perhaps the thing that strikes on the most about Ill Wind, even down to its title, is how cynical it is. And I mean *those exact words*. The common statement among Star Trek: The Next Generation defenders (as opposed to Dominion War fans who try to spin “redemptive” readings of Star Trek: The Next Generation) is that it was “idealistic”, “optimistic” and “hopeful”, in contrast to the grimdark edgelord pessimism they see in later science fiction series. This has a grain of truth about it, but the reality, as reality is, tends to be more complicated. Gene Roddenberry certainly wanted it to be idealistic and conflict-free, but this rankled just about every writer who worked on the show because they couldn't conceptualize of narrative without conflict, because they couldn't conceptualize of narrative without Aristotelean drama.

As such, there were plenty of Star Trek: The Next Generation stories in the post-Roddenberry years that were cynical in the Dominion War/Battlestar Galactica way (no surprise they were penned by the same people who went on to helm those shows): Just take a look at “The Most Toys”, “Reunion”, “Ethics”, “I, Borg” “The Pegasus” or “Preemptive Strike”. Or, you know, don't. But while Star Trek: The Next Generation has been no stranger to cynicism, the difference this time with Ill Wind is in the *way* it's being cynical. The Dominion War/BSG style of cynicism tends to involve a lot of shock-value betrayals, deaths, and fetishistic fascination with “how far” a character can be “pushed” while still remaining “moral” (and indeed calling into question notions of morals and ethics in general). What Diane Duane is doing in Ill Wind is different: A classic Star Trek: The Next Generation trick, the violent rivalries and shocking twists and betrayals are all happening outside of the Enterprise, but unlike the common refrain from critics of this series, the crew doesn't sail in and wag their fingers either.

Far from it, the Enterprise crew are, thanks to both diegetic and extradiegetic reasons, kept at arm's length from interfering in any way. All they can do is sit back and watch and do what they can to keep a merely hopeless and unpleasant situation from snowballing into an actual catastrophe. But there's no judgment passed here either: While we're obviously meant to sympathize with Captain Picard and the rest of the crew, they can't even be be bothered to muster up any energy to be righteously indignant anymore, let alone be compelled to try and fix things. The Enterprise seems brokenhearted and sad, but perhaps more than anything else tired. Deanna, the empathic heart of the ship, even straight-up says she's getting drowsy. This is not their fight, and if everyone out there doesn't want to listen to what they have to say anymore, then so be it. The long cosmic dark awaits.

Apart from that, we get further development on the character studies that will increasingly become the bulk of Ill Wind. While it was set up last issue, now Captain Picard and the Mestral are explicitly being paralleled as people of duty, honour and loyalty whose service to those ideals has pulled them in different directions. Duane does something clever here, because the narrative roles Captain Picard and the Mestral play here are the same that, in other series, would be filled by love interests. But they're very explicitly not, a sign Duane understands that Star Trek: The Next Generation's maturity precludes the need to throw some stock titillation and shipping bait at its readers every story. And furthermore, the Mestral's “burden of the crown” speechifying is obviously meant to be taken with a serious grain of salt, honourable and loyal as she may be in other areas (Starfleet doesn't want Captain Picard to sail either, but he's OK with it, and he's not even absolute ruler of two billion people), a tacit setup for the direction her character arc will go in future issues. One last time, the character development goes to the guest stars, but it's not our responsibility to make them learn their own lessons.

But perhaps that famed optimism is still here. Deanna's only sleepy, not tired, as she stresses to us. And when Commander Riker asks Captain Picard if he wishes he was “out there with them all”, Jean-Luc says that he is.

May 16, 2017

Après le Dîner

Phil was nice enough to cite me in the most recent of his (wonderful) 'Proverbs of Hell' series. I just thought I'd be cheeky and repost a little reheated morsel of the stuff of mine that he referred to... because I think it's quite interesting.

Phil was nice enough to cite me in the most recent of his (wonderful) 'Proverbs of Hell' series. I just thought I'd be cheeky and repost a little reheated morsel of the stuff of mine that he referred to... because I think it's quite interesting.

In Hannibal Rising, the boy Hannibal emerges from privilege, from the Renaissance, from the Sforzas (a right bunch of bastards). But he also emerges from the aftermath of Barbarossa. His childhood tutor is a Jew who escaped the holocaust. He is adopted by a woman from Hiroshima. His early years are haunted by mention of the Nuremburg trials. He is born of the 20th century's ultimate horrors.