Philip Sandifer's Blog, page 52

April 28, 2017

The Anti-Potter, Part 2: Jeremy Corbyn and the Billionaire's Authorthority

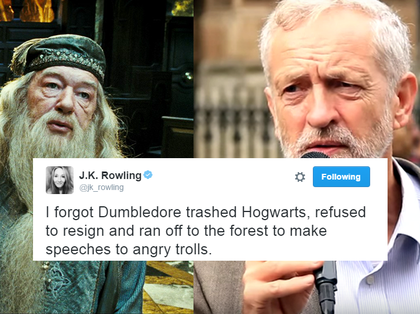

Should Jeremy Corbyn somehow manage to win the United Kingdom’s General Election on 8th June, J. K. Rowling will be forced to take a principled stand against his rule. Which will presumably mean that she’ll go and sulk in a tent for several months. After all, she’s been vocal, even vociferous, in her opposition to his leadership of the Labour Party since before it started.

Well… it might not be a tent. She’s a billionaire, remember. This is something that people seem to forget, at least in effect. But I imagine sulking would form a large part of it, even if it took place in very comfortable surroundings. And snarking on Twitter. That would be a big part of it too. She’s done a lot of that about Corbyn already. She has tweeted and retweeted truckloads of declarations of his unelectability, his incompetence, etc. She piled on in the fake ‘Labour anti-semitism’ row, in which a handful of incidents - ranging from the piffling to the wantonly misconstrued to the fabricated - were talked up by the media into the chimera of a Labour Party stuffed with raging Jew-haters, with Corbyn as either Anti-Semite-in-Chief (Ken Livingstone presumably being his deputy) or as a passive permitter of all the internal Labour Party kristallnachts. (This is all the more reprehensible, by the way, because there is evidence that anti-semitism is on the rise out in the real world. But, surprisingly enough, it’s mostly not coming from Left-wing people who have issues with Israel.)

This isn’t to say that Corbyn is perfect. I’m not here going to elaborate a full position on Corbyn. If I did, I’d have many complaints to make. But let’s just state something: when Labour loses on 8th June, the largest single factor will be Corbyn’s unpopularity, which is largely a media artifact. I mean, you don’t have to especially admire Jeremy Corbyn to realise that when this manifestly sincere man is widely considered less competent, likeable, and trustworthy than Theresa fucking May - a woman he routinely trounces during PMQs; a woman so blatantly machiavellian that she does the Skeletor laugh, on camera, in the House of Commons - something funny is going on somewhere.

Of course, one expects the Right-wing press in Britain (which is almost all of it) to vilify the Labour leader, and especially to vilify Corbyn, a man with a long-history of principled socialist activism and campaigning. The British Right-wing press thought Ed Miliband was a Marxist. To them, Corbyn must look like an absolute lunatic. Seriously, this is what they think. Anyone who departs so far (which, by the way, is nowhere near far enough for me) from the Westminster consensus (i.e. the dogma of neoliberalism) must simply look, to them, like a twisted nutcase. But the fact is, he looks like a twisted nutcase to most of the ostensibly Left-leaning British press, i.e. the Guardian, the Independent, and some magazines… well, just the New Statesman, if we’re honest. (The Indy’s claim to be on this list is really just down to the fact that they have one or two left-leaning columnists.) Consequently, he looks like a twisted nutcase to many of their readers.

The real damage to Corbyn, at least from the direction of the media, and at least if we just shelve the issue of the BBC, has been done by this supposedly Left-leaning press. And this is the quarter with which J. K. Rowling has chosen to loudly align herself. Just the other day she retweeted a Sarah Ditum article from the News Statesman website, trashing Corbyn once again.

Now, I’m not one to criticise somebody for snarking on Twitter. God, no. That’s a person’s God-given right. I’ve even been known to indulge in it myself occasionally. But of course, when J. K. Rowling snarks on Twitter, people pay attention. Lots of people. I’m not even criticizing that, particularly. If I had that kind of platform, I’d use it. Damn skippy, I would. And she’s entitled to her opinion, and to promote it as loudly as she likes… and, naturally, since she’s a woman on the internet, she’s been nastily attacked for having opinions and defending them, which is wrong, and people shouldn’t send abusive tweets when she annoys them, etc etc etc. (I trust, by now, you all know how sincerely I mean all that, despite my casual way of saying it.)

But the reasons for Rowling’s influence… or maybe I mean ‘influentialness’... are interesting. There are a lot of people who pay attention to her not just because she wrote some books they love, but also because she says a lot of things they like. She’s outspokenly liberal, and even mildly leftyish, on social issues. She makes a big deal of paying her taxes… which is a baseline minimum requirement really, but which our world makes seem like something special. Like it or not, a lot of people like being able to cite her as being ‘on side’. They like the idea that someone they admire, someone who created characters they treasure, is with them, on the side of progress, etc. This is an understandable impulse. Most of us a prone to it from time to time, in one form or another. I’ve certainly enjoyed the knowledge that an artist I like agrees with me about stuff.

But Rowling, owing to the ridiculous and disproportionate success of her Harry Potter books, punches way above her weight in terms of influence and culturally-perceived moral authority. Really… the books aren’t that good. Not even the first three, which are genuinely good examples of the kind of thing they’re content to be: kids’ books. But it’s more than just their success. It’s also the fact that they are self-consciously and self-proclaimedly moral tracts about ‘tolerance’. Especially as they go along, the books acquire a thematic obsession with notions of tolerance and intolerance, freedom and persecution, and specifically of these things in relation to social attitudes to inborn identities. The whole ‘mudbloods’ thing escalates from being a sub-theme in the second book to being the main signifier of the evil of Voldemort. He is evil because he is a racial purist. When the import of the ‘mudbloods’ thing was ‘Draco Malfoy bullies Hermione because he thinks he’s better than her because of something about herself she can’t change - that’s horrible’ everything was fine. That’s a nice moral for a kids’ book. (Though I question how much impact it has. Bullies don’t perceive themselves as bullies. There will have been kids who were bullies at school who read that and rooted firmly for Hermione.) But when it becomes the basis for texts which imagine themselves to be complex meditations on prejudice… well, things get sticky.

But it’s this muddled project - and it really is very badly muddled - of using the Potter stories for the purposes of pontificating about tolerance that leads at least part of Rowling’s audience to prize her words and thoughts on issues of social justice. But this is a very, very bad idea. I say this not just because of her resolute opposition to an actual socialist leading the Labour Party, or just because she’s a billionaire Hollywood mogul (and thus in a different social class to most humans, with manifestly different and opposed interests to the rest of us), but even just by what’s in her books.

Apart from stuff I talked about last time (i.e. the ambivalent attitude to literacy: snobbery towards the illiterate combined with suspicion towards any concept of literacy as engagement in ideas, particularly oppositional or marginal ideas) there are other huge issues, some of which I’ve mentioned before in other pieces.

The books are filled with sentient ‘magical creatures’ who reflect ‘other’ races. The Elves, the Giants, the Centaurs, the Goblins… and I do mean other races, because the standard human being in Harry Potter is white. I’ll get into the specific problems with these representations another time. Suffice to say… it ain’t pretty. In fact it all gets as racist as all fuck. For now I want to take a little digression…

*

I confess to having been irritated by the whole ‘Black Hermione’ thing. Not by the decision to cast a Black actress as Hermione in the Cursed Child play. I don’t care about that, except insofar as I’m just generally glad when I see culture getting less smotheringly white. Nor am I referring to the longstanding habit of some to depict Hermione as Black or Asian in their fan-art. I think that’s usually quite nice. No, I mean the attendant phenomenon of people insisting that Book!Hermione is Black, or that it is possible to interpret Book!Hermione as Black. Because… well, sorry and everything… but she isn’t, and it isn’t. Book!Hermione is white. Because everyone in Harry Potter is white until Rowling tells us otherwise, either specifically (i.e. “Angelina Johnson was a Black girl”) or tacitly… by, say, calling a character “Padma Patil”. The Hermione-is/could-be-Black brigade often hinge their ‘arguments’ on a line in one of the books (Prisoner of Azkaban, I think…) in which Hermione is described as “very brown”. The trouble there is the context. You know, that stuff that enables us to understand what is happening and/or being said to us? Firstly, if Hermione is “very brown” because she just is, why are we being told about it? Why bring it up, apropos of nothing? And why now, suddenly, in Book 3? Secondly, she’s just come back from a foreign summer holiday. That’s the immediate context. Rather than opening the possibility of Hermione being a Black or Asian person, I’d say the line is definitive proof of her whiteness. I’m all for letting the reader construct their own reading… but when you start trying to ‘prove’ your reading using textual evidence that actually refutes your case… I mean, nobody would stand for it if I used isolated and context-free lines from Henry IV to prove that Falstaff is actually an extremely brave soldier.

The use of textual evidence is interesting in that it suggests a certain mindset on the part of fans. It simply isn’t enough for them - or at least for a certain type of them - to interpret the books the way they like. They want their interpretations to be ‘true’ or ‘correct’. And the reason they turn to Rowling - either in the text of the books, or in person - for settlement of the issues is because they think she gets to say who’s right and who’s wrong. Ironically, they have fallen back onto the idea of the authority of the author in an attempt to validate their own act of creative reading. And this is something they have learned from Rowling and her books. Because they books are written as collections of immutable facts about a place that Rowling alone fully knows and controls. This is partly why so many Potter fans go into ecstasies about Rowling’s use of continuity, and her ostensible mastery of the principle of Chekhov’s pistol. What she actually does, generally, is rifle through the bric-a-brac of previous books, find something she can re-use, and then act like its appearance in the earlier book was carefully-planned foreshadowing. This is important to her, and to her fans, because it reinforces the idea that Rowling has absolute knowledge of all the ‘facts’ about the Wizarding World, which is a coherent place with a past and a future, all of which is contained within the mind of the Omniscient Author. (I’d be tempted to suggest that this impulse comes from a subconscious awareness of the very historylessness of the Wizarding World that I talked about last time. It’s a defensive overreaction.). The experience of reading the books, if one buys into this perspective, is the experience of being told things, having things explained to you, by an authority figure who has total mastery over all the facts. The adventure becomes the gathering of all the facts, the accumulation of ‘knowledge’, the consumption of information. This is further reinforced by the fact that Harry spends a huge amount of his time being told things, and having things explained to him, by authority figures… whether is is eavesdropping on them from under his Invisibility Cloak, or listening to yet-another long-winded infodump from Dumbledore.

Rowling wouldn’t want to flout her own vocal social liberalism by appearing to step on the idea of a Black Hermione. Indeed, Rowling has embraced Black Hermione, or at least the possibility of Black Hermione, or at least the validity of interpreting Hermione as Black… which is interesting, and which must’ve hurt her. Not because she’s racist. I believe she’s genuinely a conscious anti-racist. It’s rather because she considers the Potter books to be dispatches from a universe of ‘facts’ about the Wizarding World that she keeps stored inside her head. This can be seen in the way she has imparted information about the pasts and futures of the characters, and nuggets of data about ‘what really happened’, since the publications of the books. The most notorious of these is, of course, her ‘revelation’ that Dumbledore was gay. (Again, we won’t go into that here, but trust me… it’s coming.)

(I should acknowledge that much of what I’m saying has been anticipated by others, especially by Dan Hemmens at Ferretbrain.)

Rowling has - in my opinion quite shamelessly - exploited the Black Hermione thing to try, once again, to make her Potter stories seem redolent of far more liberalism than she actually evinces in them. Whiteness is absolutely the default assumption in the books. Now, I don’t actually have much of a problem with this. It’d be unfair to single Rowling out for special opprobrium. But I don’t like that many, including Rowling, seem to want to deny it. And it becomes an issue when millions of people think of these particular stories as a primal cultural narrative, a moral-political touchstone… and specifically a touchstone of tolerance and anti-racism. (I will have more - and angrier - things to say about this at a later date.)

But again, the even more fundamental issue here is one of authority. Or… if I may once again indulge my habit of coining awkward new words… Authorthority. Authorthority is when people think of stories as dispatches from a world The Author knows exclusively and fully; of reading as the act of slowly being fed a list of facts about an unreal place by The Author, who is the ultimate arbiter of what is ‘true’ in that place. This is a bad way to train people to think, especially if you’re then feeding them your pronouncements about racism and politics and tolerance, etc. And this is as good a description of how millions of people - including, disturbingly, Rowling herself - seem to experience the Potter stories. Which is less than ideal when the ‘facts’ about tolerance and intolerance and politics that are being fed to the readers are, to be honest, pure liberal bourgeois ideology. (This sort of thing is hardly unfamiliar to any genre fan, least of all Doctor Who fans… and yet we have the luck to have no over-arching Author figure, just a succession of ‘stewards’ towards whom we tend to feel little reverence… precisely because we tend to think that they have temporary charge of something that is, in some way, ours. This isn’t always entirely healthy, to put it mildly, but it’s a different type of unhealthy to Authorthority as it appears in Rowling and Potter.)

Now, clearly, if there’s one figure in the Potter books who has any authority to decide what is or is not true, it’s Albus Dumbledore. But this power is not in opposition to Rowlings, to The Author’s Authorthority. It is Rowling’s Authorthority. Dumbledore’s manipulations, omissions, and explanations are Rowling’s - to us, the readers, who spend almost all of all the books seeing everything from the perspective of Harry, who is the main subject of Dumbledore’s manipulations, omissions, and explanations. Clearly, then, Rowling thinks - albeit unconsciously, I’m sure - of Dumbledore as being her spokesman, her mouthpiece… as her method of controlling the flow of ‘facts’ about the world she’s created… and more, as the authority figure who settles things one way or the other. He is her Authorthority, personified. Consequently, he is also her way of informing the reader about what’s right or wrong in morality and politics. In fact, he does this constantly.

All the more reason for Rowling to be perturbed by the fact that people often say Corbyn reminds them of Dumbledore. (God, I’m being really mansplainey today. But at the end of the day, I think the fact that she’s a billionaire capitalist is far more pertinent than the fact she’s a woman.)

Of course, Corbyn is not actually remotely like Book!Dumbledore, or even particularly like Film!Dumbledore. Nevertheless, he reminds many people of the Dumbledore that lives in their heads.

Book!Dumbledore (and Film!Dumbledore, who is a softened version, but still basically the same character) isn’t a wise, clever, compassionate, fair-minded battler for truth and justice. Going by the text, he’s a capricious, foolish, selfish, reckless, cynical, manipulative, calculating old autocrat who enjoys unearned privilege and, the odd gesture aside, never does anything about injustices he knows to be wrong. He allows children under his care to be abused in various ways - from the psychological abuse of ‘sorting’, to punishments which put them in direct physical danger.

As with several things, this sort of stuff isn’t a problem when we’re reading whimsical kids’ books. It becomes a problem when the books bloat - in several senses - and Rowling starts thinking she’s writing serious and dark political Fantasy set in the same silly world of the early books. It forces us to start asking questions about that world that were simply inappropriate if we’re just reading jokey kids material.

Dumbledore unabashedly plays favourites, allowing Harry to get away with outrageous infractions because he adores him, presumably because he believes Harry to be inherently superior to all the other kids. He says as much, even at one point claiming that Harry’s blood is worth more than his. (Again, I’ll pass over this here, but we’ll be coming back to this another time.) Meanwhile, he has relentlessly lied to Harry, kept things from him, and cynically raised him to be slaughtered at the appropriate time, manipulating and grooming Harry to the point where he is psychologically primed to sacrifice himself.

(Rowling is, of course, manifestly unaware of the fact that she actually wrote Dumbledore as a total bastard, much as she is unaware that she wrote Harry as a selfish little shit. As it happens, I agree with her on one thing: I really don’t think there’s much similarity between Dumbledore and Corbyn. Dumbledore and Theresa May, however...)

But for my purposes today, the most salient issue is that Dumbledore is wedded to the status quo, despite his occasional and two-faced criticisms of it. He never challenges the inherently undemocratic nature of Wizarding society. He has never actually done anything substantive about the abuses he fitfully acknowledges Wizards have committed against oppressed groups in their society. He happily stands by while his society wipes people’s minds - indeed, he does this himself at one point, to one of his own pupils, to protect himself from impeachment. Because him no longer being Headmaster of Hogwarts would change things, you see… and above all else, that must be stopped. That really is the quintessential moral imperative of Dumbledore, and of Harry, and of the books: things mustn’t change. (I know, I know, Hermione and SPEW… but that’s yet another of those cans of worms I’m going to open some other time.) That’s why Voldemort is evil: he wants to change things. That’s why Dumbledore is good: he wants to preserve things just as they are, injustices included. After all, we can remember to denounce the injustices occasionally, and maybe Hermione will get into the Ministry of Magic, and that’ll sort everything out. I’m told Rowling has dispatched yet more fact parcels about events after the books in which she says Harry and Hermione become great reformers. I’ll just remark that a) nothing like that is in the books, and in the books anyone who wants to change anything is always either evil or stupid, and b) they’re presumably still doing it from within the status quo… so the first thing to do, if you want to change anything, seems to be to accept the profoundly undemocratic Ministry as an inevitable fact of life. Hmm.

The Corbyn/Dumbledore comparison violates - at least potentially - Rowling’s Authorthority, her power of veto. As I say, what always seems to matter to Rowling is whether or not people are getting their ‘facts’ right about the Wizarding World. To her, there is one correct interpretation of the Potter stories, and she is the arbiter of it. For her readers, the reading consists of the act of slowly and passively waiting for J. K. Rowling to reveal this interpretation to you. And she does this by getting you to slowly and passively wait for her to reveal fact after fact after fact about the Wizarding World. Furthermore, if the facts she reveals clash with her official and licensed interpretation of events and characters, then she either studiously avoids noticing this, or - if pushed - is always ready with a retcon. What is important, at every stage, is that the readers are ‘on message’. She will occasionally ‘allow’ a creative reading where it appeals - Black Hermione for instance - but even that is telling. Fans take the idea to her and she sanctions it. This process is important to both.

This same approach is extended to the real world, hence her habit of using metaphors and analogies drawn from her own books to illustrate points about current politics. This isn’t just a habit she’s recursively picked up from her readers, through being in near-constant contact with them via social media. It’s even more recursive than that, because they themselves picked up the impulse to do it from the books.

And this is because, as the books progress, Rowling becomes ever more obsessed with the idea that they are dark and serious treatises on racism and prejudice and authoritarian government, etc, and impassioned pleas for tolerance and equality, etc. As I say, we’ll examine such claims for the books a bit more carefully another time. Suffice to say, this idea doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. But that itself works, because the kind of political consciousness displayed in the books is quintessentially centrist and mainstream liberal… which means, in practice, that it is superficially progressive but actually based on a total unquestioning acceptance of the economic, gender, and racial hierarchies of the status quo, of Western capitalism and imperialism.

I’d even go so far as to suggest that her Authorthoritarian mind-set is a function of what seems to be a fundamental impulse to defer to power, to say that ‘what is’ - certainly in terms of the basic structure of society - is right, by definition.

Rowling has, to anticipate later posts, literally reified the status quo, described it as magical, and depicted it as a glorious fantasyworld that is unquestionably better than this one… and yet is almost indistinguishable from this one. (Remember what I said last time about the effable mirror, the cameo reflection.) She has literally turned an idealised ideological reflection of the world we currently live in into a heavenly version of itself, specifically designed for mass consumption as magical wish-fulfillment. A lot of the wish-fulfillment comes from the idea that we can expect that heavenly version to provide any socially liberal progress we desire. Paradoxically, we are always reminded that Rowling’s world is dark and scary… and yet the only ostensibly dark and scary things in it are either the people it has crushed and subjugated, or those who want to change it in some way. Once again, as I described way back in the Merlin essay, the thing to do if you want progress is not to try to change the world, that makes you bad or stupid, but rather to wait for a fundamentally good status quo to eventually provide.

And there you have it. really. Corbyn - for all his many real faults - is someone who wants to change the world in some way. He’s not a revolutionary… but, as I say, the point is that he looks like one to people like Rowling. He wants to do more than be the personification of a benevolent status quo, the way Tony Blair was (a million or so dead brown people aside). This is the heart of the problem that people Blair (who has been going around telling people to vote against his own party, but who routinely still gets fawned over by the supposedly left-leaning media), and the Guardian and the Indy and the NS, and the Labour Right and most of the Labour PLP, have with Corbyn. And it’s the heart of the problem Rowling has with him.

Let me remind you once again: the woman who is regarded as being ‘on the Left’ and ‘progressive’ etc, and as a powerful moral voice, and even by some as an arbiter of moral truth, is a billionaire Hollywood mogul capitalist. Does that make her an inherently terrible person? No, that’s not what I’m saying. But it does mean that she has a totally different perspective on the world to almost all of the rest of the human species, a perspective based on totally opposed and conflicting interests.

Rowling has spoken out to defend the welfare state… and this is an instructive thing to look at. In so doing, she has often used her own story. But her story is a fluke series of events in which a single mother on benefits won the publishing contract lottery, published some above-average kids books, and then some below-average fantasy books notionally in the same series, sold the rights to Warner Bros., and happened to become a billionaire as a result. She is not typical. She is not a meaningful illustration of why we need social benefits and the welfare state. It’s almost as if she thinks the point of welfare is to help people to eventually become massively financially successful, rather than to help them… y’know… survive and retain some degree of dignity. The end-result of providing people with the welfare state and benefits seems to be, ideally, that they will go on to become productive members of capitalist society, either as billionaire entrepreneurs or, at least, as happy wage earners and taxpayers. It is, as is often the case, unfair to single Rowling out. These are hardly unusual assumptions on the liberal-left reformist side of things. However, as is also often the case, she’s an instructive illustration simply because she’s so vast and dense a cultural event. And the illustration reveals her fundamental reliance on the ideology of the capitalist status quo. Here, for instance, it is the myth of meritocracy. Ironic, given that in her books she recycles a version of the Calvinist ‘Doctrine of the Elect’. But then, as Weber pointed out, there are points of convergence between Calvinist doctrine and the ideology of capitalism (though he got the sequence wrong if you ask me). In the Doctrine of the Elect, some people are just saved - and that’s just the way it is. In the doggerel version, this becomes a way of saying that some people are rich because they’re just… well… better.

*

I suspect Rowling’s fundamental problem with Corbyn is that she perceives him as weak, as a failure. And there is literally nothing she hates more than weakness and failure. Seriously, read those fucking books. They detest weakness and weak people. There is nothing in those books but contempt for anyone who is weak, who fails. This is why Gryffindor is clearly the only really good house to be sorted into: it’s the house of the strong. Slytherin prizes success at any cost, so you’d think that, by my take on her, she’d like them too… but remember: they lose all the time. The definition of the contemptible.

Rowling’s primary howl against Corbyn has always been the main mantra of the supposedly-left anti-Corbyn media: that he’s “unelectable”. This has, as I say, become a classic self-fulfilling prophecy. Of course, Corbynism was always a gamble on a long game. I knew that when I signed up to it, just as I knew there’d be sell-outs and compromises along the way. Corbyn is a genuine socialist but he’s a reformist, working within the parliamentary system and not actively trying to overthrow capitalism - so he and I have fundamental disagreements. But imagine what could’ve been achieved by now if even just the supposedly left-media had swung behind him. Not by slavishly praising him no matter what he did, but simply by giving the poor fucker a chance, by not systematically misrepresenting and undermining him. Imagine if the Right in the Labour Party hadn’t launched a farcical coup against him which fatally undermined his public image. Imagine if people like Rowling hadn’t, from the start, anathematised and belittled him, declared him simultaneously a clown and an authoritarian. But then, we couldn’t expect anything but what we got… precisely because people, including Rowling, act according to the perceptions of the world, which are shaped by their place in the world, by their class positions and allegiances. (That is, of course, precisely the sort of observation almost entirely missing from the Potter books. Yes, rich and posh people are snobbish in those books, and the middle classes act very middle class… but it’s because of inborn, innate qualities. Ironically, given the books’ ostensible opposition to prejudice based on bloodline, in the books people’s personalities are in their blood. But again, I’m going to come back to this.)

The irony is that Corbyn is almost certainly going to lose on 8th June, not because he’s weak - fucking hell, you only have to look at the sheer stubborn grit he showed when he refused to resign, something Rowling criticised him for! - but precisely because he is hated by people, like Rowling, who perceive him as weak. And they make sure to perceive him that way because they are filled with even more fear and loathing by the idea that he - and the latent socialist idea he represents - might actually be, or might one day become, strong.

But hey, what do I know? I’m just an angry troll, apparently.

*

Oh, we’re at the end. (The irony is that my Potter posts are getting longer and longer and longer.) So it’s time for me to kill of a beloved regular character, because I want my readers to understand that I have a profound understanding of the reality of death. Daniel, you're up. I was going to kill off Jane (I picked her at random) but I'm not sure female main characters really matter enough to kill.

*

P.S. I wrote a bit about the whole 'mugwump' thing but I cut it for reasons of space (ha!) and also because it didn't quite fit anywhere. My Patreon backers will get exclusive access to it. (Hint hint.)

April 27, 2017

Eruditorum Presscast: Smile

Another Thursday, another Eruditorum Presscast, this time with Daniel Harper and I talking about Smile, which neither of us disliked particularly, and which both of us found loads to complain about.

If that sounds fun, listen here. If that doesn't sound fun, LISTEN ANYWAY OR WE'LL TURN YOU TO FERTILIZER.

April 26, 2017

Permanent Saturday: Axis Mundi

In Garfield, everything has a voice, or has the potential to have one. Birds, mice, spiders and household appliances (not to mention cats and dogs) all have readable internal dialogue. Everything has a soul. Everything is a potential spiritual agent. Naturally it's only the animals, plants and objects who display regular awareness of this fact, because Garfield is about Western modernity and we as humans have forgotten such things in our society. Recall, however, that it is us as the audience who have privileged access to the thoughts and concerns of these creatures even as the humans in the strip do not. There's hope for us yet.

(Of course, the strip goes back on forth about this depending on what makes the better joke on that day. If you are still looking for the laws of physics underlining the “Garfield universe” you are manifestly missing the point of this series and are approaching it utterly the wrong way.)

This level of awareness comes, however, at the price of extremely heightened empathy. Those who feel deeply their connection to the myriad other souls in nature may also find their feelings of suffering and loss to be magnified as well. Especially in the West and Westernized cultures, where collective institutionalized violence and depersonalization have become so normalized. Garfield himself expressed concern over this in a strip decades ago: Jon once asked him “Wouldn't it be great if these walls could talk? Imagine the stories they could tell”. To which Garfield responded (for our benefit, of course, not Jon's) “Every time a light bulb burned out it would be like a death in the family”. Hearing the voices of others compels you to listen, and to treat the speakers with the same respect and personhood you would wish for yourself.

This is the scenario the first panel sets the audience up for. Garfield stands over the tree stump, implied to be of the same tree he is frequently seen climbing, wondering what happened to it. Garfield and this tree have a relationship which, like his relationship with the dog next door, is humoursly likened to a human nine-to-five punchclock job. Garfield climbs the tree and goes next door to get barked at by the dog because that's what he “does”, in the modern definition of the word: When we ask what a person “does”, we're really asking how they sell their labour because of how ubiquitous capitalism has become to Westernism. So the joke in those situations is pointing out the absurdity of the way we schedule our lives in Western modernity by showing how silly it is when other animals and plants, who are no less “natural” than humans are at their core, engage in the same behaviour. It's grafting a Western capitalist kind of relationship onto a fundamentally innate, intimate natural one.

But that's all tangential, because that's not what this joke is about. It is, however necessary context for Garfield's reaction in the first panel. There's a quote in one of the last episodes of the UK version of The Office where Martin Freeman's character muses about how ironically poignant office coworker relationships are: We work our lives away every day, and, as a result, we get to know the people we work with far better than we do the friends and family we *choose* to spend time with, simply because of the clockwork regularity with which we see them, and the sheer scope of how long that time truly is. This is the first part of Garfield's concern: His daily schedule has been disrupted and he's taken aback first by that, but moreso by the unexpected absence of someone who was a constant part of it. If you and I have an unspoken agreement to meet for breakfast every day in the same place, you would naturally be confused and worried if one day I didn't show up in that place, even if it turned out I was just seated a few tables down.

But the tree isn't just absent as Garfield's dialog (which, reading left to right as we do in Western cultures, is the first thing we see in the strip) would first imply. We next see that Garfield is looking a a tree *stump*, which would imply the familiar tree is in fact dead, killed when someone cut it down. Loss and the accompanying grief is certainly the ultimate disruption of our daily schedules, which casts Garfield's opening question about where the tree has gone into an entirely different light. At first glance, this seems like a shockingly unexpected traumatic upheaval of Garfield status quo, something akin to the strip we saw a several weeks ago depicting the aftermath of a gigantic sinkhole opening up in the comforting familiarity of the Garfield yard/garden set. But that strip was ultimately a subversion, leading to a gag about Garfield's narrative logic. And this strip turns out to be a subversion too, though a somewhat more subtle one.

The second panel gives us the necessary anticlimax. The tree is thankfully not only still alive, but also apparently *on vacation*, a punchline that is fulfilled in panel three where the tree tells us it's moonlighting as a surfboard in Hawai'i. Note first how there's a bonus throwaway joke in the form of a muted visual gag: Once again flagged by an absence following the conclusion of an event we don't get to see (the hypothetical felling of the tree), we're left with the baffling implications of how a tree *cut itself down* and somehow flew itself to the Hawaiian Islands. But that's not the actual primary joke here, that's just context-The real joke is at the expense of our fears of death and loss. We know, of course, the tree is still alive, and this is a cleverer storytelling trick than is probably immediately apparent. Far from being dead, the tree is merely somewhere else in a different state, in this case in the form of a surfboard.

Being a surfer myself (or someone who fancies they know their way around a board and have a loose understanding of the culture at the *very* least. I do, after all, currently live in the *very* landlocked mountains), I want to firstly commend this turn of phrase. Because if the tree was fashioned into a surfboard, this means it *must* be a paipo or alaia; traditional wooden surfboards. Most commercial surfboards produced for Western audiences in California and Australia and the like are all made out of fiberglass, epoxy and foam in an industrial process so eco un-friendly it should most certainly attract outrage from the supposedly environmentally conscious surfing culture. Paipos and alaia (the only real difference is whether the board in question is a long- or shortboard) are made out of repurposed wood through traditional sustainable methods, and were the original boards used in surfing going back to time immemorial. That the tree went to the Hawaiian islands is even better (the surfing joke could have worked just as well at Huntington Beach, Oceanside or Bondi), because Hawai'i is the birthplace of not just the wooden surfboard, but surfing itself: Garfield didn't just make a surfing joke, it made a surfing joke that flags an understanding and respect for the actual history of the sport. The Paws, Inc. staff is nothing if not meticulous.

If we read the tree as “dead” (which we shouldn't, because it's not, at least not as we understand the term, but for immediate sake of argument let's do), then this means, in the language we as Westerners are most accustomed to, it's been given a “second life” in the form of a surfboard (nicely, a tool designed to help humans better move in sync with natural rhythms). But a more accurate description of what's happened is that the tree's life-consciousness has transmuted from one form into another: First from the tree, then to the board. Which is a much closer fit for a non-western, non-modern understanding of what we call “life” and “death” actually are: Predicated on a deep connection to natural cycles and feminine deep time, this understanding of reality posits that conscious experience does not cease, but constantly shifts around changing form as it goes. If we were to pair this with the fact the tree has been reshaped into a board, we might catch a glimpse of a truly primordial form of magic: The building of anything is always nothing more or less than the reshaping of matter. Creation always comes from somewhere else, and is the act of channeling and radiating energy in new ways: Inventive transformation and transmutation.

And crucially, the joke works even without the surfing connection. While we may think of a tree stump as being “a dead tree”, the tree's roots are still planted in the ground and can still grow new shoots. In fact, a common practice in responsible forest management called coppicing involves deliberately cutting a tree so that its stump can regrow, a practice which helps increase and preserve biodiversity. It's common in our society to draw an arbitrary line between humans and nature, a nasty artefact of at least so-called Enlightenment philosophy. The hand-wringing that humans are an unnatural blight on the world who are a wholly corrupting influence that the ecosystem could do just as well without is merely the dark mirror of the “Benevolent Stewardship” strain of Christian thought, wherein the West thought they were ordained by God to Lord Dominion over the beasts. It conveniently ignores the long history, particularly in the Americas, of native peoples using simple techniques (such as coppicing) to alter their environment in beneficial, yet sustainable ways (not to mention the fact nonhuman animals and plants, by their very existence do too). The entire Canadian landscape, as well as that of New England, was reshaped by First Nations peoples in the time before Europeans arrived-The colonialists were just too ignorant to notice. There's hardly such a thing as an “unspoiled wilderness”, but we can make healthy ones by working with our environments instead of against them.

Garfield's modus operandi has been, since day 1, to satirize banal Western capitalist malaise by showing how ridiculous it looks when nonhuman actors, creatures who have not forgotten their inner fundamental naturalism, act out the same sorts of rituals. With Garfield's opening question now turned thoroughly on its head, today's strip is an elegant and perfect demonstration of this: Casually reminding us of our own roots on a multitude of levels, the cat asks not the plaintive “Where did you go?”, but rather the inquisitive “Where are you now?”. A subtle difference, yet a truly profound one.

Original Strip: April 18, 2017

April 24, 2017

The Proverbs of Hell 5/39: Coquilles

COQUILLES: Coquilles are shells, referring either to shellfish like oysters or to casseroles served in a shell-shaped dish. The poetic meaning would involve something about how people are just shells for the higher angelic spirit within. The crass (and likely intended) meaning is a visual pun based on what happens when you flay wings off of someone’s back.

COQUILLES: Coquilles are shells, referring either to shellfish like oysters or to casseroles served in a shell-shaped dish. The poetic meaning would involve something about how people are just shells for the higher angelic spirit within. The crass (and likely intended) meaning is a visual pun based on what happens when you flay wings off of someone’s back.

POLICE OFFICER: Do you have a history of sleepwalking, Mr. Graham?

WILL GRAHAM: I’m not even sure I’m awake now.

The best interpretation of this line, of course, is that even Will has noticed the weird way in which the sky moves at the wrong speed and fucking stags keep showing up, and has come to realize he lives his life in a strange and murderous dreamscape. Either way, though, he’s right.

HANNIBAL: I’d argue good old-fashioned post traumatic stress. Jack Crawford has gotten your hands very dirty.

WILL GRAHAM: Wasn’t forced back into the field.

HANNIBAL: I wouldn’t say forced. Manipulated would be the word I’d choose.

Manipulation is a vital yet inchoate topic in Hannibal, and this line sets up much, both about the next episode and about Jack. Later in the episode, as Jack tells Will that he’d feel guilty about all the murders he didn’t help stop if he returned to teaching (a statement designed in part to ensure he would), the blunt reality that Jack is an exceedingly manipulative man. This does not mean that his genial and reasonable persona is a facade - he is legitimately a good person who seeks to make the world a better place by preventing murders. But his goodness is ruthless, and he does not question it, which can and does prove tragic for those pulled along in its wake.

JACK CRAWFORD: Mr. and Mrs. Anderson according to the register. Mutilated, displayed. Thought it might be the Chesapeake Ripper but no surgical trophies were taken.

This marks the first mention of the Chesapeake Ripper, setting up “Entrée,” where that plot finally begins in earnest. This is a somewhat odd decision - this plot starts up early enough to have clearly been in mind all along, and yet it’s curiously and conspicuously absent from the initial setup, in ways that, through the first four episodes, actively fail to make sense. The biggest of these, of course, is a matter of narrative necessity - Will can’t make the obvious connection between the copycat killer and the Chesapeake Ripper because the end-of-season plot hinges on him not noticing it. Nevertheless, the fact that Will has clearly been consulted on this case at some point seems like something that should have come up in his early conversations with Jack.

JACK CRAWFORD: Who’s mocking who here?

WILL GRAHAM: He’s not mocking them. He’s transforming them.

Budish’s killings are a tacit mirror of Francis Dolarhyde’s, with the person being transformed through the acquisition of wings being the victim instead of the killer. Notably, where Dolarhyde seeks to transform into a demonic figure, Budish transforms his victims into angels, furthering the sense of him occupying the negative space around the absent (and as of yet unmentionable) Dolarhyde.

WILL GRAHAM: I need a plastic sheet to cover the bed.

In a show full of grim comedy beats, this may be the grimmest, played with sublime reluctant awkwardness by Hugh Dancy.

HANNIBAL: At my table, just the cruel deserve cruelty, Mrs. Crawford. Which is why I employ an ethical butcher.

BELLA CRAWFORD: An ethical butcher? Be kind to animals and then eat them?

HANNIBAL: I’m afraid I insist on it. No need for unnecessary suffering. Human emotions are gifts from our animal ancestors. Cruelty is the gift humanity has given itself.

JACK CRAWFORD: The gift that keeps giving.

Hannibal’s account of cruelty contradicts itself, though in a Luciferian way as opposed to an incoherent one, where the words “need” and “unnecessary” carry a near-infinite weight of ambiguity. And yet there is the sense of a genuine principle being expressed here - Hannibal is consistently shown to have genuine affection for Bella, and his insistence on defending his ethics appears to come out of a genuine desire for her good favor. And it is worth stressing that there are significant ways in which Hannibal’s self-defense is true. Nowhere is he shown demonstrating physical sadism, for instance - he does not relish killing his victims in particularly agonizing ways, or work to prolong agony. When he mutilates people, it tends to be with surgical precision and anesthetic agents. The conceptual agonies he’ll inflict on people are limitless, and he is in no way averse to necessary suffering, but he has no interest in physical pain for the sake of it, and indeed is inclined to view it as rude.

Notably, the line also calls back to Will’s assessment of the crime scene, where he describes being flayed as the killer’s “gift” to his victims.

HANNIBAL: A tumor can definitely affect brain function, even causing vivid hallucinations. However, what appears to be driving your Angel Maker to create heaven on Earth is a simple issue of mortality.

WILL GRAHAM: Can’t beat God, become him.

The third possibility, of course, is the one that Hannibal takes: can’t beat God, become the Devil. The prospect is unmentionable within this episode, ultimately erased by the way in which the Angel Maker's crimes are an inverted version of Dolarhyde's. (That and the need to focus on cancer instead.)

HANNIBAL: Jack gave you his word he would protect your head space. Yet he leaves you to your mental devices.

WILL GRAHAM: Are you trying to alienate me from Jack Crawford?

Blatantly yes, although it’s difficult to divine Hannibal’s motivations in doing so. Generally speaking, Hannibal has seemed inclined to push Will deeper into his work for Jack, deliberately opting not to intervene to protect Will’s mental health. Indeed, Jack most certainly did not promise to protect Will’s headspace - he farmed the job out to Hannibal. The best guess if one insists on an in-universe explanation is that Hannibal is trying to cut Will off from his support systems, but treating Jack as a support system instead of as a force pushing Will deeper into the sordid dreamscape is bizarre. The realistic answer is probably that it’s a somewhat sloppy bit of writing designed to make the episode’s closing scene more of a payoff.

BEVERLY KATZ: So he makes angels out of demons.

JIMMY PRICE: How does he know they’re demons?

WILL GRAHAM: He doesn’t have to know. All he has to do is believe.

And yet he’s right - the victim in question was impersonating a security guard, and Budish somehow identifies this. Given that his victim selection is elsewhere shown to be “he kills the people who appear to him with burning heads,” this becomes the point where it is impossible to deny that there is a supernatural dimension to the show. The only remaining ambiguity is whether Hannibal is a supernatural creature, which, if Budish gets to be, is hardly much of an ambiguity.

BELLA CRAWFORD: Women who love their husbands still find reasons to cheat on them.

HANNIBAL: Not you. Yet you seem more betrayed by Jack than your own body.

BELLA CRAWFORD: I don’t feel betrayed by Jack. And there’s no point being mad at cancer for being cancer.

HANNIBAL: Sure there is.

Bella’s illness is expanded from a subplot in Silence of the Lambs. She becomes, however, the show’s first rock solid female character, in part on the back of Gina Torres’s performance, but mostly on the back of the fact that, unlike Alanna Bloom, it’s always clear what she’s doing in the plot. Her animated fatalism is a coherent position that imparts a distinct and complimentary flavor to the overall show. Hannibal’s declaration that it makes sense to be mad at cancer for being cancer is one of the quieter revelations of his hubris: the idea of being angry at a raw force of nature comes naturally to him. Fittingly, then, this episode shows Hannibal seeming to have a better grasp on the killer’s pathology than Will does.

HANNIBAL: You’re not unlike this killer.

WILL GRAHAM: My brain is playing tricks on me?

HANNIBAL: You want to feel such sweet and easy peace. The Angel Maker wants that same peace. He hopes to feel his way cautiously inside it and find it is endless all around him.

Hannibal’s line is originally a description of Francis Dolarhyde, continuing the sense of parallelism between them. It is notable that the focus on peace as a physical feeling of tranquility and low stimulation reinforces the suggestion of Will as existing on the autism spectrum. (See also, slightly earlier in the scene, Will contemplating zipping himself into a sleeping bag.)

The stag is revealed as not entirely an imaginary construct as Will sees its literalizing form and visibly comes to the brink of drawing the connection. Not only does Hannibal have a stag statue lying around for seemingly no reason other than poking at Will’s mental constructs some more, but Will clearly recognizes the stag statue as something closely related to what haunts his dreams. This only makes sense if they are not entirely dreams - if, in other words, he’s not entirely awake now.

Further confirmation that Budish is a supernatural being comes in the fact that he was able to do this to himself. This also introduces what will become a recurring trope in the series of serial killers being killed in accordance with their own aesthetic. Usually it will be Hannibal who does this, as part and parcel of his compulsion to dominate his victims, but in this case Budish does it himself, a natural conclusion of his underlying fear. It’s notable, of course, that Budish’s art is nearly mistaken for Hannibal’s at the episode’s outset.

ELLIOT BUDISH: I will give you the majesty of your Becoming.

Once again Budish is used as a tacit invocation of Francis Dolarhyde, for whom the notion of “becoming” is crucial. The scene, however, is heavily reworked from the script and turned into a hallucination on Will’s part, presumably to resolve the problem that the script had Jack Crawford standing in the doorway doing fuck all through this scene and, more broadly, to avoid the rather ridiculous excess of Budish climbing back down after flaying himself. Instead it becomes a confirmation of Will’s claims of deteriorating mental health immediately prior mixed with vague but pleasantly portentious foreshadowing.

JACK CRAWFORD: I don’t want you to be alone. Now or ever.

BELLA CRAWFORD: We’ll beat this together?

JACK CRAWFORD: This is your fight. But I’m in your corner and I’m not going anywhere.

BELLA CRAWFORD: I appreciate that, Jack. But I’m not comforted by it. I know that’s what you need. To comfort me. But I can’t give you what you need.

The writing of Bella’s terminal illness and Jack’s reaction to it is refreshingly nuanced, with Bella consistently written as something other than the perfect and beatific sick person while still remaining sympathetic. Jack, meanwhile, is unflinchingly a good person who says the right things, and yet as with Will his good intentions and the utter defensibility of his actions does not, strictly speaking, matter.

JACK CRAWFORD: What do you want, Will?

WILL GRAHAM: I’m going to sit here until you’re ready to talk. You don’t have to say a word until you’re ready, but I’m not leaving until you do.

This moment of male emotional bonding seems to be the motivation for the episode’s otherwise strained conflict between Jack and Will. This is well outside the show’s wheelhouse, and is inadequately paid off in subsequent episodes, but is nevertheless a nice moment that goes a long way towards finding a basis for Jack and Will’s relationship other than Jack’s exploitation of Will, even if it probably would be more interesting to actually see their scene instead of ending the episode at the stoic male failure to talk.

April 23, 2017

Smile Review

It’s hard to avoid the “damn with faint praise” opening of “well it’s better than In the Forest of the Night.” In a whole bunch of very obvious ways, after all, it is. The balance between the ridiculous and the dramatic is better struck. Cottrell-Boyce sets himself the non-trivial Ark in Space challenge of spending half the episode with nothing but the TARDIS crew wandering around an alien setting figuring out the rules, and he generally rises to the challenge. And there’s a sense that he’s figured out what the program can and can’t do well, and so is avoiding pitfalls like relying almost entirely on child actors or an outlandish visual spectacle that’s ultimately going to amount to throwing some traffic lights in the middle of a Welsh forest and pretending it’s good enough.

The “damn with faint praise” aspect, however, comes from the fact that you can’t actually put the bar much higher than “oh, hey, Cottrell-Boyce avoided fucking up this time.” The script still never soars. Worse, as with In the Forest of the Night, the moments where it tries to soar are generally its weak points. The script has an awkward habit of leering in and insisting that you find it clever, and these bits don’t often correspond to when it’s being clever. The repetition of the “skeleton crew” joke twice in rapid succession and the thickly laid on “can’t you call the police” line are the two most obvious examples. But equally frustrating are the things it doesn’t unpack - the declaration that the Vardies are a form of sentient life isn’t set up nearly well enough, and more broadly the resolution is full of ideas that are actually worth exploring, but that the script has left no time to explore because it wanted to be an ostentatious two-hander for a while.

Another way of looking at this, then, is that Cottrell-Boyce has retreated emphatically to Doctor Who standards. We’ve seen this story before, varyingly as New Earth, Planet of the Ood, Silence in the Library, The Girl Who Waited, and probably a few others I can’t be bothered to think of. And fine, we’ve clearly seen next week’s before as well, but Sarah Dollard can at least be trusted to find new angles on things. Cottrell-Boyce, on the other hand, ends up using the Doctor Who standards to carry the weight that his actual scripting can’t.

The most straightforwardly clear of these standards, of course, is the “new companion sees the future for the first time” template. And this is the clear point of spending more than half the episode as a two-hander - to give Bill a nice long stretch of time to settle in and define herself in the companion role. In this regard, Cottrell-Boyce has been given a rough brief. The last time another writer was handed a new companion’s second story it was Neil Cross doing The Rings of Akhaten, which actually shot quite late in the Series 7 block. Everyone prior had either been by the showrunner or during the Davies era where the showrunner did a full rewrite. Which means that Cottrell-Boyce is stuck writing Bill without really knowing her. To compare with Clara again, the equivalent stories for her were Hide and Cold War - later in the run ones that weren’t about Clara so much and where her characterization from Bells of Saint John and The Rings of Akhaten could cover her lack of depth somewhat. Here there’s no cover save for Pearl Mackie's basic charm and skill (which is admittedly considerable), and the problem is thrown into sharp relief by the degree to which this is the "Bill steps out" set piece. The most obvious clanger is our sci-fi knowledgeable companion not knowing what cryogenic storage looks like, but other than the shoehorned in “two hearts” scene it’s tough to find anything here where Bill isn’t being written as generic companion. Which, again, fine, that’s going to happen for some early episode or another, but why on Earth would you make it this one?

Which brings us back to avoiding the damning with faint praise. Because whatever the flaws of In the Forest of the Night, and it was unequivocally a hot mess, it was at least shooting for something that the show had never done before. And for all the technical smoothness of Smile, it’s a bog standard “companion’s second episode” story approached with ruthlessly workmanlike efficiency and basically nothing else. I’ve always preferred a noble failure to a cheap success, especially with Doctor Who. It may be better than In the Forest of the Night. But much like I’d rather rewatch The Time Monster than The Sea Devils, I’ll take Maebh Arden and her misfit classmates than the banal polish of this any day.

It sure would have been nice to see the emojis premise go to someone who wasn’t a cynical curmudgeon prone to writing lines about “vacuous teens.” Yuck.

For the most part the emoji badges were cut to too often and too pointlessly, being used to make explicit what was already perfectly clear, but a couple of them, most obviously the Peter Capaldi grumpy face emoji, were genuinely hysterical.

So, um, why were the Vardies enraged that one of their Emojibots got blown up given that the Emojibots are explicitly not the actual robots but just interfaces they use? Not, to be clear, that I give a damn about the plot hole, but given that the only reason this was established was for a pretty pointless “now that’s what I call a robot” gag one does wonder what the point of that was.

A somewhat stranger gap in the plotting is the utter incompetence of the colonists. Do they just not know how the Vardies are supposed to work? Is that why a dozen of them grab guns and try to shoot their entire city? I mean, you can see why the Doctor decides to fuck them over in the denouement, but eesh.

The ending tease for Thin Ice is interesting inasmuch as it’s just not an approach towards an inter-story cliffhanger we’ve seen lately. It’s a very 1960s Doctor Who approach - something akin to the radiation meter creeping upwards at the end of An Unearthly Child or the Macra claw on the time scanner in The Moonbase. The use of an elephant, which recalls the opening of The Ark, only increases that sense. I wish I could say it worked, but alas it just exacerbated the chaotic jumble of the episode’s resolution.

Right, OK, let’s pick at the resolution a bit. I already groused about a minor plot hole, but it’s worth pointing out why this rankles, which is that the resolution just seems to have no idea what to do. It’s exploding with ideas, many of them quite interesting, but there’s a sense of Cottrell-Boyce just throwing new ideas into the script in a desperate hope that they’ll add up to something. Slave races! Indigenous populations! The ultimate survival of the human race (which is a bit of an odd assertion given that a few scenes earlier it was reiterated that these aren’t the only human colonists, but hey)! It quickly stops being clear what the Vardies are actually supposed to be a metaphor for, instead plunging headlong into Baker and Martin concept vomit. Only somehow I suspect the emoji jokes aren’t going to age quite as well as the lurid 70s thrill of The Claws of Axos.

Man, what’s with me and Pertwee comparisons today?

Another way of looking at this is that the oversignification that comes from Cottrell-Boyce’s unchecked spew of liberal glurge gets interesting in places. For the most part I like Cottrell-Boyce’s inclination to cram in politics like it’s the Cartmel era, even as I find his politics banal as hell. But for every “oppressed underclass as indigenous population” there’s something like the kind of cringey rent joke at the end. Or the episode’s worst conceit, the idea of the Doctor as a policeman.

One political implication I’m particularly amused by is the apparent moral necessity of blowing things up. As I noted on social media this week, Doctor Who’s ethics are historically “don’t punch Nazis, but definitely blow them up, and possibly blow up their entire planet as well.”

Apparently Cottrell-Boyce got the idea for this by asking a scientist what he thought the biggest threat to humanity was and getting the answer AI. Reports suggest that this scientist was robotics professor Andrew Vardy, hence the robot names, but I can only assume he’s got Kit Pedler reincarnated on a computer somewhere and just forwarded the question along to him.

Of course, the end result of Cottrell-Boyce talking to a bunch of scientists is that he came up with the “machines becoming lethal by dint of doing what they’re made for” idea that’s been Moffat’s default setting for twelve years now.

Jane groused about Lawrence Gough’s direction last week. He does better this week for the most part - there are some lovely wide shots and uses of reflections here. But he’s kind of let down by the set design, which alternates between being flat and, in the engine room, weirdly contrived. Still, the Emojibots are a nice design.

American viewers got the second episode of Class tonight. This is the same link as last week, as they were released together in the UK, but here was my review of that. US reviewers seem pretty happy with Class, but then again, so was I at this point, and I stand by thinking this episode was pretty interesting.

Right, that’ll do for this week. Podcast Thursday with Daniel Harper. Proverbs of Hell tomorrow morning. If you like this shit, please consider backing the Patreon. Thanks.

Ranking

The Pilot

Smile

April 21, 2017

Little Window

You were supposed to be getting another Shabcast - with another great guest - this week, but life had other plans. So, having staked everything on that, I am left without an essay to post. So you'll have to make do with the third chapter of one of the novels I'm currently occasionally writing. Here are chapters one and two. My Patreon sponsors saw an earlier draft of this chapter ages ago (under a different title). And if that doesn't make you salivate with an irresistible desire to give me money, I don't know what will.

You were supposed to be getting another Shabcast - with another great guest - this week, but life had other plans. So, having staked everything on that, I am left without an essay to post. So you'll have to make do with the third chapter of one of the novels I'm currently occasionally writing. Here are chapters one and two. My Patreon sponsors saw an earlier draft of this chapter ages ago (under a different title). And if that doesn't make you salivate with an irresistible desire to give me money, I don't know what will.

There were times when Iza envied Ria. Ria didn’t have spiders in her hair, or webs plastered across her face. She didn’t have dust falling into her eyes. She wasn’t losing the skin on her elbows and palms. Her fingernails weren’t splintering as they dug into brickwork. She didn’t have to hold on for dear life. She wasn’t alive. Iza felt guilty thinking this, but thought it all the same.

“This is amazing,” said Ria. For once, she didn’t sound sarcastic or cynical.

There was no room for Ria in the dark behind the walls. But she was there. She had followed Iza into the vertical passageway. Iza could hear Ria’s voice. It was as if she was behind her. But behind Iza there were just cold bricks, bare but for the filth of time and darkness. Iza had her back pressed against them. There was nowhere for Ria to be. Even so, Ria’s voice came from behind her. This was an old trick, of course. Sometimes, in the old days, Ria had spoken to Iza from inside bathroom cabinets, or toilet cisterns, or shopping bags.

“Why didn’t you tell me about this before?” asked Ria.

She spoke aloud. There was, of course, no need for her to keep her voice down.

“I only found out about it after the last time you… left,” whispered Iza. She felt Ria scrutinising her. She felt guilty, despite the fact that she was telling the truth.

“I didn’t leave,” said Ria, “You sent me away. Remember?”

“If I did, I didn’t mean it,” hissed Iza.

She almost told Ria how many times she’d wished for her. Again, she wanted to ask Ria where she’d been, and why she’d stayed away for so long. But this didn’t seem like the time and place.

“We’re here,” whispered Iza.

They’d reached the top.

The cavity ran down the entire height of the house on the right side. It was only just big enough for Iza to squeeze into. Every time she did it, it was a tighter fit. She supposed that was good. She didn’t want to be small forever. But it meant that one day she’d be too big to get in. Too big to make any more secret visits to the top floor of the house. If when that happened… would that mean she’d never see her mother again?

Iza, with Ria somewhere near her, stared into Mary Park’s top floor apartment. The suite she’d chosen to make her sanctuary, her cave, her comfortable oubliette. The fortified place that the woman who wrote books about queens and princesses, and who had once presented television programmes about queens and princesses, had chosen to make into her castle. A turret for a self-imprisoned Rapunzel. London-greyed stucco for stone walls and ramparts. Barred and shuttered windows for arrowslits and embrasures. A lake of silence for a moat. A locked door for a drawbridge. An electronic keypad for a sentry.

Not even Mary’s Personal Assistant - a young woman called Jane Austin, much to her own apparent embarrassment - knew the code to get in. She had to wait for the door to be opened from the inside. And then she had to count to ten, slowly, before coming in, to give her employer time to scuttle out of sight.

Jane had been astonished to learn that Iza didn’t know the code either, which Iza thought was stupid of her.

“I’d be the last person she’d tell,” Iza had said, “after all, I’m the first person she wants to keep out.”

Jane had gone quiet. A perpetually flustered and self-conscious young woman who had worked for Mary since before her seclusion, Jane came and went regularly. She ferried in and out of the apartment anything that needed ferrying. She did all Mary’s shopping… which meant, in practice, that she told the housekeeper Mrs Chatterjee what to buy and then took it up to Mary. She usually stopped and talked to Iza for a while, insisting on making her tea and awkwardly chatting over the kitchen table.

Iza had eventually realised that this was Jane performing another task set by her employer. Iza had made her confess it. Jane had wriggled uncomfortably under Iza’s interrogation, as if being asked to reveal corporate secrets. But Iza had wormed more out of her than ever before. Iza learned that Jane rarely, if ever, saw the inmate of the shuttered tower. She told Iza, with the air of someone divulging a mildly shameful secret, that she and Mary tended to conduct conversations from opposite sides of an internal door, left slightly ajar.

Iza got the feeling that, uncomfortable as she was, Jane was relieved to be talking. And then Iza got it. The conversation made Jane feel that she and Iza were equals. Girls downstairs, talking furtively about the adult upstairs. It meant, for Jane, that she didn’t have to think of Iza as her responsibility. Which suited Iza. She didn’t want to be Jane’s responsibility.

Apart from anything else, the whole idea that Jane should ‘keep an eye on’ Iza had probably just been a vague handwave of Mary’s. An afterthought. Iza thought it was unfair on both Jane and her. Iza didn’t dislike Jane… though she suspected she only had her job because of her amusing name. She felt more or less the same way about Jane as she felt about Mrs Chatterjee. She was glad both of them turned up regularly, but she didn’t like the pitying way both of them looked at her. Neither of them knew that she actually saw her mother quite a bit. Not even her mother, who always made sure to keep her laptop camera switched off on the rare occasions that she would Skype with Iza, knew how often Iza saw her.

“How many times have you watched her from in here?” asked Ria, almost as if she’d been listening to Iza’s thoughts.

“I don’t know,” whispered Iza.

Even whispering, her voice sent little echoes up and down the cavity, as did her every movement. Ria’s voice didn’t echo.

Truth was, Iza had lost count.

*

In the taxi, on the way home from seeing Dad, Iza realised she hadn’t read a single word of the book. Just the title and the author’s name.

She handled it. She almost opened it to start reading. But no. She and Ria needed privacy. They couldn’t read it together and chat about it as they read, not in public.

That was always how they’d done it in the old days. When there’d been a book or magazine they both wanted to look at, or a film or TV show they both wanted to watch, Iza had found some opportunity to go off and be by herself - at least as far as everyone else was concerned. That way she could chat openly with Ria without people deciding she was mad. The sisters had discovered early on that they couldn’t communicate by just thinking at each other.

In the taxi, Iza had put the book down again, and checked her phone. Still no response from Mum. No messages or missed calls. Now that she thought about it, her last Skype conversation with Mum had been almost a year ago. But then actually talking to Mary was unsatisfying at best.

She held the phone so that Ria could see, but so it wouldn’t look odd to the taxi driver, just in case he looked back. Things like that had happened before.

Once, a few years ago, Iza had conducted a long conversation with Ria in one of the school squash courts, without realising there were sixth-formers in the viewing gallery. Her echoey, one-sided conversation had drifted up through the glass. Iza had been sent to see a counsellor. Iza told her she was rehearsing her lines for the school play. Luckily, the woman had accepted this - relieved to think she didn’t have a case on her hands - and neglected to check with the drama teacher, who probably didn’t even know Iza’s name.

“I’ll cancel the letter to your parents then,” the counsellor had said, smiling. Iza had smiled back.

Even so, word got around. Iza Park talked to herself. But she could live with that. It wasn’t as if the consequences had been dire. On the contrary, most people had just been kinder to her the stranger they thought she was. Getting bullied or taunted, she came to see, was far more about who you were than what you did. Some people could be as strange as they liked and never be at risk. Others would get it no matter how quiet and conformist they were. They unknowingly sent out the wrong kinds of signals, and those signals were picked up by the people who were always on the look out for them. Those same people saw Iza Park’s strangeness and interpreted it favourably. Iza Park was interesting. Iza Park was unusual. Iza Park was artistic and spiritual, probably, they imagined. Iza Park, of course, had a very rich mother who was on TV, and a very rich father who built massive buildings. Iza Park’s mother was a baronet’s daughter, and her father would be a life peer one day. And Iza Park sent no signals. Iza Park was a dead line.

Meanwhile, amongst adults, her parents were a get-out clause of a different kind. Both were almost always somewhere else. He was always rushing from skyscraper to gated community to gentrified street. She was always being chauffeured from location shoot to academic conference to book launch.

If any adult thought there was something wrong with Iza Park, they blamed it on Mary and George Park. Which suited Iza. And it seemed fair, a way for them to help her. A way that would suit them: from a distance, and with no actual effort involved. Iza also found that the less she criticised them, the more other people were willing to do it for her.

The only people who expressed any serious dissatisfaction with her had been her parents themselves. It had soon become clear to Iza that she was not the girl they’d wanted. That girl was outgoing, ambitious, a social butterfly in pupal stage, preparing eagerly for debutantery and ball-attendance, already networking her future career contacts in her house common room. But Iza hadn’t turned out like that. She’d become something different to the little child they’d adored. That child had been as gregarious as a dolphin. A particularly sociable dolphin. The kind of dolphin whose name is always at the top of the list whenever the other dolphins decide who to invite to the next fishing-and-splashing-around party. But as she got older, Iza withdrew, and came to prefer her own company… at least, that was what it looked like to everyone else.

On some level, Iza understood that her relationship with a non-existent sister, who tended to criticise her and analyse her, was probably not what people would call ‘healthy’ if they found out about it. But they persistently didn’t. Adults really weren’t much different to those kids who kept an eye out for the weakness or strangeness of their peers; they saw it in some places, and missed it in others where it simply seemed inappropriate. And in any case, she thought health, like normality, was probably overrated. Healthy people dropped dead from heart attacks while jogging. It happened directly outside their house at least three times a year.

The ambulance and the fallen jogger were long gone by the time the taxi dropped them back in Maude Square. To distract herself, Iza tried again to initiate a conversation with Ria on that topic, but was interrupted by the taxi driver calling her back to tell her she’d left her book on the back seat.

By the time Iza walked inside the house and closed the door, Ria was already in the hall, back on her step at the bottom of the stairs, looking out through the pillars again.

“Get the photo,” said Ria, unsmiling.

“I don’t know where it is,” said Iza.

“Rubbish,” said Ria, “it’s on your bed. You put it down and left it there before we went out. You kept on putting it down and leaving it somewhere and walking off when we were here before.”

“Did I?” asked Iza.

“You put it down in the taxi,” said Ria.

“Yeah but that was just…”

“Photo,”said Ria.

“But don’t you want to…?” began Iza, holding up the book.

“Don’t I want to… what?” asked Ria. Iza followed Ria’s meaningful gaze until she saw that the hand she was holding up didn’t actually have the book in it.

She’d put it down on the hall table the moment she’d walked in. She went to get it.

“I thought you’d want to read…”

“I do,” said Ria, “but you obviously don’t. I think we should just move on to the photo before you finally succeed in losing the book.”

Iza blinked at her. Under Ria’s assessing stare, Iza felt guilty… though she wasn’t sure what about.

This was another old feature of their relationship. The compromise negotiated. Accepted tacitly. With one of them conscious of it and one of them not. Until Ria - the conscious one - broke it. Iza had often raged at herself for understanding herself less well than a girl who wasn’t really there.

“Photo,” said Ria again.

They set off upstairs, Ria in front.

Iza glared at the back of Ria’s head.

“Iza,” said Ria, without turning around.

Iza stopped, wondering if Ria had somehow seen the face she’d pulled.

“Don’t you think you should bring the book?”

Iza went back to the hall table. The book was still there.

The book finally retrieved, they found the photo where Ria had said it would be.

Iza put it in the book.

Iza didn’t open the book.

She felt an almost overwhelming urge to put it down somewhere and walk off.

Only Ria’s gaze stopped her.

“I’m scared,” said Iza.

Ria softened.

“It’s okay,” she said.

“I just feel like…”

She faltered. She couldn’t find the words.

“Like we’re about to do something we shouldn’t do?” asked Ria. “Like we’re about to find stuff out that maybe we don’t really want to know?”

“Yeah,” said Iza, “that.”

“I can’t make you do anything you don’t want to do,” said Ria, holding up her hands.

“But you want to know, don’t you?” asked Iza.

“Yes. Don’t you?”

“Yes, I do. And I don’t. I’m scared to know.”

“You’ve got more to lose than I have.”

It was just a statement of fact. Ria was never nasty about the really serious stuff.

“Maybe we could wait and talk to Mum,” said Iza, buckling, “She might get back to us.”

“To you.”

“Yeah.”

“Okay,” said Ria, “if you think so. You know her better than I do.”

A moment slunk past in watchful silence.

“Do you miss her, when you’re… wherever you go?”

“I don’t go anywhere,” said Ria. “Sometimes I feel like there’s somewhere I could go, or should go, when I’m not here. But I… I can’t find it.”

It was the first time Ria had ever said anything like that. But Iza wanted her question answered.

“But do you miss her?”

Ria scowled.

“Yes,” she snapped, looking down. And then, quietly: “I miss both of them.”

“So do I,” said Iza.

Ria looked up, as if to challenge. Then she saw Iza’s face and looked down again.

“Let’s go and have a look at her,” said Iza.

Ria looked up.