Grant Goddard's Blog, page 8

July 23, 2023

The unmagical mystery tour : 1973 : Piggott’s Manor, Letchmore Heath

There was a loud knock on the front door. Who could be visiting unannounced after dark? Certainly not Mr Dickinson from ‘The Pru’ who always called during daylight hours to collect monthly premiums in cash for our insurance policy. The opened door revealed two men in uniform whose van parked outside had a strange aerial on its roof. What had my father done? Was he about to be forcibly dragged away from our suburban Orgonon? No. The men said they were from the Post Office’s Radio Interference Service and were investigating a recent spate of complaints from residents in surrounding streets of strange patterns interrupting their television viewing. Could they come in and inspect our equipment?

My parents’ enthusiasm for modern gadgets had equipped our living room with one of Camberley’s first state-of-the-art Bush colour televisions to receive the ‘BBC2’ service launched earlier in 1964. It had required the installation of a different aerial on the roof and an amplifier to successfully receive the UHF signal from a far transmitter. Although our own television reception had been fine, the men from the ministry believed that the amplifier must be faulty, transmitting interference instead of receiving signals, a problem they had sleuthed to our house. We were required to switch off the amplifier and temporarily refrain from watching BBC2. Hullabaloo and Custard had sold us a technicolour dream though I was now to be deprived of my daily look through the square or round window with Big Ted and Jemima.

The technical problem was eventually fixed and our BBC2 viewing resumed, even after the annual Licence Fee was doubled to £10 in 1968 for the 20,428 UK households that owned a colour TV, a dismal figure that betrayed the initial failure of the technology’s launch. We missed the first black-and-white BBC1 transmission of ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ on Boxing Day 1967 because we always spent the holiday at my grandparents’ house next door, stoically without a television. Instead, we gathered in our living room expectantly on 5 January to watch BBC2 repeat the programme in colour. This film premiere had been trailed as an artistic triumph for the world’s biggest pop group.

My parents owned all The Beatles’ albums to date and had watched their films at the Camberley Odeon. Earlier that decade, my father had bought a second-hand Uher reel-to-reel tape machine and had recorded the group’s performances broadcast live on the BBC Light Programme with a microphone held to the speaker, while his family was ordered to remain silent. The resultant tapes were played repeatedly in our house at high volume, years before homemade audiocassette compilations became possible and decades before Spotify would offer the same outcome at the press of a mouse button.

Once the 52-minute film of embarrassingly indulgent pop icons acting sillily in and around a bizarre coach trip had ended, we looked around to gauge each other’s reactions. It had been an incomprehensible and barely entertaining viewing experience, we agreed. The next day at school I wrote a short account of our evening in my ‘day book’ and drew an accompanying colour picture. No classmates had watched the film. My female teacher likely presumed my parents to be hippies. Our home’s complete collection of Beatles albums came to an abrupt halt. My mother transferred her musical affections to non-stop Herb Alpert.

After this artistic disappointment, The Beatles faded from my childhood. I learned that John Lennon had moved into a mansion (‘Tittenhurst Park’) in nearby Ascot when one of my father’s clients was appalled to discover the identity of his new neighbour. I recall our family being dragged along by my father to walk around Bruce Forsyth’s house on Wentworth Drive as a possible home, the estate agent spouting that a Beatle lived nearby (Tittenhurst Park is 1.6 miles away). I was excited by our potential neighbour but appalled to contemplate a home adjacent to a golf course in the middle of nowhere. Luckily it never happened.

Years passed during which our family circumstances changed irreversibly. One morning in 1973, my father turned up unexpectedly at our home and insisted I accompany him on a trip. I adamantly refused but my mother insisted I go, hoping I might learn something about my father’s current ‘circumstances’. Only months earlier, he had quit our home for good and since had done his best to humiliate and impoverish his former family. He had even gone to court to demand regular access to his two-year-old daughter whom he had never wanted in the first place. One Friday a month, he would turn up and drive off with my baby sister, leaving my mother fretting inconsolably the whole weekend as to whether we might ever see her again. What ‘childcare’ my father provided at weekends we never learned, as he had been notably absent in his other children’s upbringing and his new lover was a mere teenager.

There was no conversation during our car journey. Not LITTLE conversation, NO conversation. My father talked though I said absolutely nothing. He still drove his left-hand-drive American Motors Javelin AMX sports car as fast and recklessly as he ever had, breaking speed limits, overtaking on blind corners and generally terrifying me. Only the air conditioning kept me cool. I hated being there. Since leaving our home, my father had ignored me, ignored my birthday, ignored Christmas and sustained his total disinterest in my life. I had no respect for him because he had never done anything to earn respect from me. He seemed not to have the faintest idea of what a father should say or do for his children. Tellingly, after he had left, I never missed my father at all. Rather than tears, I felt relief. Why would I miss someone who had only ever used my talents to further his own greedy ambitions?

After an hour and a half of stoney silence, we had travelled past Elstree and arrived before a huge mock-Tudor mansion in extensive grounds. He parked facing the front of the house and its luxurious lawns, telling me he had to go inside for a meeting and would leave me in the car for a while. I was just pleased not to have to suffer any more of my father’s dangerous driving and not to have to be in the company of someone who had always felt like a stranger to me. I switched on the car radio and listened to music.

I saw lots of people all dressed in similar orange medieval-style robes coming and going from the mansion and walking along its driveway in singles and in groups. I had never seen anything like it. Not in Britain anyway. I had seen photos of Buddhist monks in picture albums of faraway lands. But it felt eerie to be seated in a car in deepest rural Hertfordshire, surrounded on its driveway by people who looked as if they had materialised en masse from another dimension and a different time. What was I doing here and, more to the point, what was my father doing here?

Only later did I learn that Beatles member George Harrison had recently purchased this property with its seventeen acres of land, then known as Piggott’s Manor, and donated it to the Hare Krishna religious movement that had outgrown its Hindu temple in central London. The property was renamed Bhaktivedanta Manor and immediately attracted a huge volume of visiting devotees, the religion’s membership having been boosted by Harrison’s very public advocacy since The Beatles years. In the present day, 60,000 visitors annually are reported to attend its religious festivals.

For me, the irony of our visit that day was that my father’s life could not have been further from the altruistic philosophies of the Hare Krishna movement. I knew he had no interest in religion and had probably never even visited a church. If he was here, it must have been for his professional advice as a quantity surveyor. Perhaps modifications were necessary to this mansion as it had functioned as a nurses’ training college since 1957, owned by St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. How could he have hustled this appointment? We knew from my father’s court papers that he claimed now to be living in the gated, 420-property St George’s Hill estate in Weybridge, home to many pop and entertainment celebrities, including John Lennon (before his move to Ascot) and Ringo Starr.

Did I meet George Harrison? No. Was I invited inside the mansion to hold the end of my father’s tape measure, a task required of me since I could walk? I honestly cannot remember. What happened next? I know he drove me home … again in silence. I was so consumed by the pointlessness of our father/son ‘road trip’ that almost everything else that had occurred was immediately eclipsed in my mind. Why had he insisted I accompany him? Was he trying to impress me? Was he trying belatedly to demonstrate his credential as a father? Or had he imagined I could help him secure a new client? I have no answers. It became our final day spent (un)together.

Half a century later, I was watching the 1969 Beatles footage in the fascinating 2021 ‘Get Back’ documentary when I noticed a Hare Krishna member who had accompanied George Harrison sat cross-legged on the floor of the group’s recording session. Memories of one of the strangest and most unrewarding days spent with my father came flooding back.

December 16, 2013

DAB Radio Switchover: Dead As The Dodo

I continued to write about DAB – in press articles, in analyst reports, in my blog, in my book 'DAB Digital Radio: Licensed To Fail' – and to talk about DAB in radio and TV interviews. I did this not because I was 'anti-DAB' or a 'campaigner' (as some described me), but because my work as a media analyst requires me to carefully examine the facts and figures and to document their consequences. I had nothing to gain personally from stating evident truths.

Between 2004 and today, the UKradio industry could have scrutinised the growing collection of analyses that demonstrated DAB consumer take-up was failing. It could have taken firm, decisive action to transform DAB radio from failure to success. It chose not to. Instead, I found myself on the receiving end of abuse, slander and libel.

Two years ago, I stopped writing about UKradio in this blog because 'Jimmy's and 'John's were pasting my analyses into their press articles, blogs and corporate statements, uncredited and without permission. Those same people then e-mailed me to ask why I was no longer updating my blog!

I write today only to bookend this blog. In recent months, it has been interesting to witness some of my 'critics' make a 180-degree turn and suddenly herald the imminent non-event of DAB radio switchover, whilst citing my analyses (uncredited) in support of their newly adopted viewpoint.

I wrote about DAB because I consider that this single issue has contributed more to the decline of the UKradio industry than all other sector issues combined. Thousands of experienced radio professionals have lost their jobs. Hundreds of genuinely local radio stations have disappeared. Much radio in the UK has become a shadow of its former self. The medium is suffering rapidly declining appeal to those aged under 30. The industry that I have worked in since 1972 is on the rocks. Most of the blame for this sorry state of affairs can be laid directly at the UK radio industry's single-minded pursuit of DAB since the 1990s, at the expense of all other objectives and at a cost of more than £1bn.

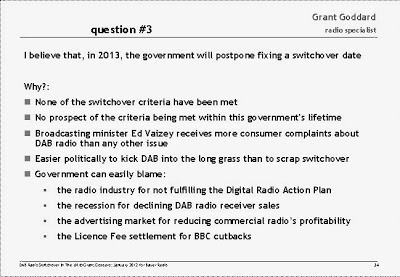

Excerpt from client presentation by Grant Goddard in January 2012

Excerpt from client presentation by Grant Goddard in January 2012In 2011, I had been invited by the government's Department of Culture, Media & Sport [DCMS] to participate in a consumer panel as part of its consultations about DAB switchover. Addressing an audience of industry stakeholders, I predicted that the government would kick the DAB radio switchover decision into the long grass in 2013. I made the same prediction in my presentation to the board of one of the UK's largest commercial radio companies [see above].

After the close of the DCMS stakeholder session, its chairperson, a civil servant in the DAB radio switchover section, leaned over to me and said something along the lines of: "You really shouldn't be writing the things you do. People don't like it, you know, and it is making them angry."

She is one of a select group of people in DCMS, Ofcom, Digital Radio UK, the BBC and RadioCentre who have earned their livings by pumping out factually incorrect reports supporting their fiction that DAB radio is a massive UK success story and that DAB switchover is inevitable. Public money and BBC Licence Fees have paid many of these people for years to mislead the public and the media about DAB radio.

Anyone with knowledge of the UK radio industry and training in statistics could have concluded from available data during the last decade that the implementation of DAB radio in the UK was headed for disaster. My analyses were not 'rocket science'. What riled the army of DAB propagandists was that my published analyses directly contradicted their bullshit. The final e-mail sent to me by the chief executive of the Digital Radio Development Bureau (forerunner of Digital Radio UK) said:

"If you are going to deliberately mis-use the information we provide to you to construct as negative a view as possible with cheap shots like those below then we just won’t co-operate with you in the future."

He saw only "cheap shots", rather than evidential analysis, in my 2008 Q2 commercial radio sector report published by Enders Analysis, which had said:

"Although it remains the most popular platform for digital radio, ‘DAB’ usage seems to be steadfastly stuck at 9.0% of total commercial radio listening, dwarfed by the continued dominance of analogue radio (69.2%). Whilst 87% of households now have access to digital TV, and 67% have access to the internet, DAB penetration remained static at 27.3% in Q2 2008. Sales of DAB receivers have failed to continue the momentum demonstrated in Q1 2008, unit sales having slowed to 108,000 in June 2008, their lowest monthly level since June 2007. With sales of DAB receivers still concentrated mainly in the Christmas period, the imminent danger is that the hardware’s relatively high average ticket price, combined with the effects of the consumer ‘squeeze’, could impact the much needed winter 2008 sales peak (552,000 units sold in December 2007).

Despite the sterling efforts of the Digital Radio Working Group (convened by the Department for Culture, Media & Sport) over the past eight months, the radio industry, as yet, seems no closer to finding an immediate solution to the problem of slow DAB take-up than it was a year ago. Although all parties agree that it is ’content’ that will drive consumers to purchase DAB radios, the major radio groups have still not unveiled any plans to stimulate the consumer market with new digital radio brands."

Five years on, the numbers may have changed but the unresolved problems with DAB radio remain exactly the same. My analyses and predictions during the last decade have proven correct … while a small army of DAB propagandists have been paid handsomely during that time to produce a massive volume of 'South Seabubble' hot air about DAB radio, partly paid for from public funds. Doubtless they will be rewarded for their failure.

Selected writings on DAB radio:· Hey Hey, You You, Get Off Of My [DAB Radio] Multiplex, November 2004· Channel 4: Radio Ambitions Aim Too High, Enders Analysis, July 2007· Digital Radio Switchover: Somewhere Over The Rainbow?, Enders Analysis, October 2007· The Future Of Digital Radio: Is It DAB?, Enders Analysis, January 2008 · Tuned Into The Future Of Radio, Broadcast, June 2008· DAB Radio: Nice Platform, Shame About The Take-Up, Enders Analysis, June 2008 · The Second National Digital Radio Multiplex: Waiting For Godot?, Enders Analysis, October 2008· Channel 4 Radio: Six Feet Under, Enders Analysis, October 2008 · The Digital One Radio Multiplex: Desperately Seeking Subsidy, Enders Analysis, October 2008 · Talking Radio: Grant Goddard [Channel 4 Radio], Broadcast, October 2008· In The Ditch With DAB Radio, The Register, December 2008· Digital Radio In The UK: Progress And Challenges, EBU 3rd Digital Radio Conference, June 2009· Germans And Swiss Snub DAB, The Register, London, July 2009· 'Digital Britain' And The Radio Sector, egta Radio Newsletter no.16, November 2009· Submission To House Of Lords Select Committee On Communications: Inquiry Into Digital Switchover Of Radio, January 2010· DAB Radio In The UK: It Ain't What You Do, It's The Way That You Do It, Radio Today 'e-Radio', April 2010· DAB Is Dead, Index On Censorship, June 2010· The First Annual Not 'The Ofcom Digital Radio Progress Report' Report, August 2010· DAB Digital Radio: Licensed To Fail, Radio Books, October 2010· Response to Ofcom consultation: 'An Approach To DAB Coverage Planning', UKRD Group Ltd. et al, September 2011 · Low Digital Take-Up Of Local Commercial Radio Prevents Digital Radio Switchover In UK, Seeking Alpha, October 2012

August 14, 2011

Growing DAB radio usage in the UK. Confused? You should be!

"The digital revolution shows no signs of slowing down, and not even the radio airwaves are set to maintain their analogue tradition, as a new [RAJAR] study suggests."

Hardly. This news story was interesting because it achieved two simultaneous feats of confusion:

• 'DAB radio' and 'digital radio' are two different things. 'DAB' is the platform on which the UK radio industry bet the farm in the 1990s. 'Digital radio' is radio received on any platform that is not analogue (AM/FM) and includes the internet, smartphones, digital TV … and DAB

• The fact that DAB listening is growing does not necessarily mean that it is replacing analogue listening at a rapid rate of attrition. Why? Because DAB listening, even after 12 years, is still at a remarkably low level.

These confusions are not accidental. At every opportunity, statements made by Digital Radio UK have sought to confuse the public by referring to 'digital radio' as if it means precisely the same as 'DAB radio.'

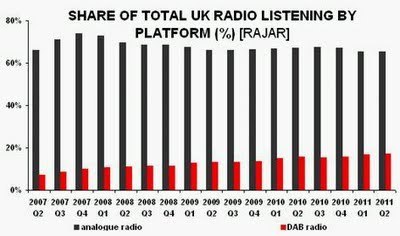

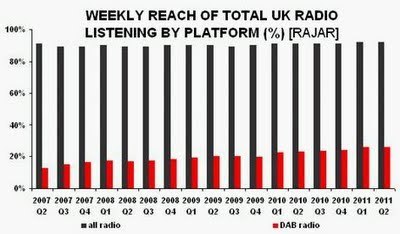

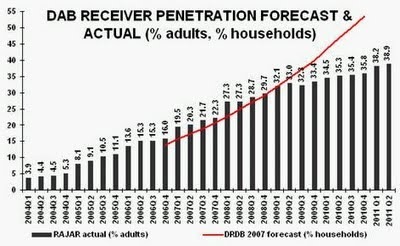

A look at the graphs below of the latest RAJAR data illustrate clearly that the "analogue tradition" in radio remains so dominant that the real question to be asked is: how come DAB usage is still so low after so many years and after so much money has been invested in content, transmission systems and marketing?

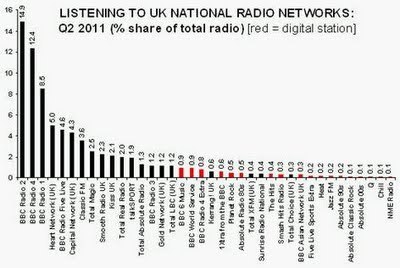

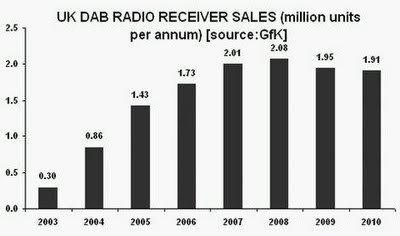

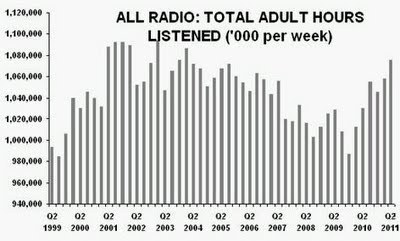

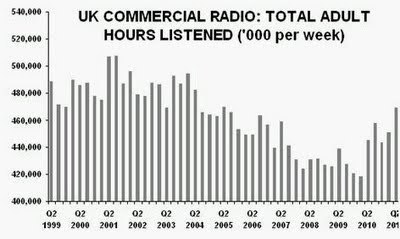

The adage 'a picture speaks a thousand words' has never been more true than with DAB/digital radio usage. The four graphs above – all taken from the industry's latest RAJAR data – say it all by showing:

The adage 'a picture speaks a thousand words' has never been more true than with DAB/digital radio usage. The four graphs above – all taken from the industry's latest RAJAR data – say it all by showing:• how little impact DAB radio has had on analogue radio usage in the UK

• how slow the rate of growth is of DAB receiver take-up and of digital radio station listening.

Far from radio losing its "analogue tradition," as the news article asserted, the old FM/AM platforms look, from these data, to be as strong as ever in the market.

One hint that some digital radio stations on the DAB platform could be on their way out is the BBC's latest decision to aggregate listening for Radio 4 and Radio 4 Extra in RAJAR. It had been doing this from the outset for Five Live and Five Live Sports Extra, on the premise that 'Sports Extra' was only a part-time broadcast station.

I would not be at all surprised to see the BBC:

• similarly aggregate Radio 2 listening with 6 Music

• similarly aggregate Radio 1 listening with 1Xtra

• downgrade its digital radio stations from full-time DAB broadcast stations to online, on-demand 'extra content' available via RadioPlayer, iPlayer and applications.

The problem with national broadcast BBC radio stations, whether analogue or DAB, is that the BBC Charter insists they must be made available universally to all Licence Fee payers. Given the huge cost of extending the BBC's national DAB transmission multiplex to near-universal coverage equivalent to FM radio, particularly at a time when the BBC is having to cut budgets massively, it would be more sensible to downgrade '1Xtra', '2Xtra' and '4Xtra' to 'red button' status whereby they offer additional content on a part-time basis. The consumer would access these Extra 'stations' via a complementary platform (IP) rather than the BBC having to shoulder the financial burden of programming them as 24-hour broadcast entities.

It would prove a convenient solution for the BBC. As it found with 6 Music last year, public controversy surrounds any decision to close a radio station, however small its audience in absolute terms. Alternatively, by pursuing the 'Extra' route, the digital stations can be re-branded, re-purposed and re-platformed away from expensive, fixed-cost DAB and towards IP, where the cost of delivery varies proportionately with the number of people using it. What better way to deliver value for money to Licence Fee payers? And what better way not to face public wrath for 'closing' a digital radio station.

As BBC Radio 2 DJ Steve Wright said on today's Broadcasting House show:

"Maybe full digitisation [of radio from FM/AM to DAB] may well take thirty years …"

As the graphs above demonstrate, there IS slow growth in DAB usage, but the rate is insufficient to replace analogue radio as the dominant consumer platform any time soon. It's time for BBC strategy to catch up with that reality.

August 6, 2011

UK DAB radio receiver sales fell in 2009 and 2010, but "digital radio sales have held up - they are flat" insists Mr Switchover

Out in the real world, as opposed to the imaginary world inhabited by Digital Radio UK, the notion that 'DAB radio' will replace AM/FM radio is already a dead duck. The only believers still worshipping 'DAB' seem to be Digital Radio UK, RadioCentre, Ofcom and government civil servants.

The evidence is transparent. The number of DAB radio receivers sold in the UK fell year-on-year in both 2009 and 2010 (by 6% and 2% respectively). These data are collected by GfK and supplied to Digital Radio UK. These numbers, together with a nice colour graph, were distributed at last month's RadioCentre members' get-together. These are industry data of which Digital Radio UK is perfectly aware.

The evidence is transparent. The number of DAB radio receivers sold in the UK fell year-on-year in both 2009 and 2010 (by 6% and 2% respectively). These data are collected by GfK and supplied to Digital Radio UK. These numbers, together with a nice colour graph, were distributed at last month's RadioCentre members' get-together. These are industry data of which Digital Radio UK is perfectly aware.Yet, Digital Radio UK's chief executive insisted in this interview on national radio that "digital radio sales have actually held up – they are flat year-on-year." This is untrue. 'Down' is not 'flat.' 'Down' is 'down.' DAB radio receiver sales peaked in 2008 and have been falling since. DAB receiver sales in 2010 were 8% below that 2008 peak. That is clearly not 'flat.'

I wonder how it is that:

• The chief executive of a high-profile marketing organisation can appear on Radio 4 (audience: 11m adults per week) and flatly state something that he must know not to be true?

• The board of Digital Radio UK does not haul him in and remind him that his job description is to 'persuade' consumers of the value of DAB, not deceive them?

• A substantial proportion of this organisation's funding is derived from the BBC Licence Fee, so the public is effectively paying for an executive to tell them untruths about consumer take-up of DAB radio?

You & Yours

BBC Radio 4

29 July 2011 @ 1200

Ford Ennals, chief executive, Digital Radio UK [FE]

Wiiliam Rogers, chief executive, UKRD [WR]

Q: Are you not disappointed with the lack of a rise in [DAB] radio sales?

FE: No, I think what the Ofcom report confirms is the solid progress that is being made. We see growth in overall digital listening, we see growth in terms of the number of homes that have a digital radio receiver in there. So, 40% of all homes now have a DAB receiver in them, we know that 47% of all listeners are listening to digital radio every week, and we have seen growth in digital listening. So I think progress is being made. I think we are in a difficult sales period for overall retailers and we have seen a decline in overall consumer electronics sales. Digital radio sales have actually held up – they are flat year-on-year. We have now sold 13 million DAB digital radios, but the key thing, just lastly, to remember is that you can receive digital radio via digital television, via a computer or, indeed, via a smartphone and many, many households and consumers have those.

Q: William Rogers, are you surprised by the lack of increase in interest in digital radio?

WR: No, not in the least. And I think we have to remember that Ford, with respect to him, is being a little disingenuous because, of course, the switchover is about people being forced to move way from analogue and onto DAB. So that's the issue we need to focus on. And what this report highlights, and I'm personally delighted to see it, is it really does shine a light on the shambles that is this proposed DAB migration.

Q: But things aren't that bad. There are increases in radio usage, as Ford has just indicated.

WR: Well, hang on a minute. The whole premise behind the switchover is that it will be, quote, consumer led. And the one thing we know from these statistics is that, whatever else it is, it's not being consumer led. As your reporter quite rightly said earlier, of the eight-and-half million radio devices sold in the twelve-month period we are talking about, four out of five of them did not have a DAB receiver capacity. And, more interestingly, of those people who were asked whether they were likely to buy a DAB set at any time in the next twelve months, four out of five of them said they were not likely to. So the consumer is making it very clear what they want and, after eleven years, it's time this thing was put to bed.

Q: Ford Ennals, one of the things that we constantly hear from listeners is the whole issue of reception. That's really what, I think, the message is that we get from people. That is what they are worried about. Whether they approve or not [of DAB], what they say is an awful lot of people can't get them [DAB radio signals] and, if they can get them, they can't get them consistently.

FE: Well, I think, where the industry and the broadcasters are absolutely unified and agreed is that digital is the future of radio in the UK. And I think it's just a matter of the timetable and the transition path for that. One of the big issues is, as you have said, is about coverage and about the ability of everyone to get a strong [DAB] signal. Now, what Ofcom have done is developed a plan to extend coverage, both of the local services and the national services, so that people can receive those services and get more confidence. But there is a direct parallel here with TV and digital television – I ran the TV switchover programme – and, back in 2006, the majority of TV sales were analogue and only 75% of the population could get digital television. Now, what happened over the next few years is we saw a very swift transition and we saw transmitters built out that so everyone could get digital TV. We'll see the same on radio.

Q: What about that, William? We don't jump 'til we have to. We don't buy 'til we have to.

WR: Look, look. Let's be clear about this. Ford Ennals is paid to market the DAB switchover, so I understand why he has to say what he has to say, because the message from this report is clearly embarrassing for him to make a case which clearly doesn't exist. There are a number of points we have to remember. First of all, the comparison with TV switchover is plainly an absurd point to make. They are not remotely, in any way shape or form, similar. And people are choosing not to endorse DAB as an alternative [to FM/AM]. The critical thing we have to understand here is three elements. First of all, ….

Q: You'll have to confine yourself to one because we are really tight for time.

WR: Okay, the fundamental problem with this whole process is that you cannot migrate an entire sector if the [DAB] platform you have chosen does not have the capacity to allow you to do so. And there are scores of radio stations in this country who will be denied the opportunity to move to a DAB platform, because the choice was wrong in the first place.

Q: A ten-second response.

FE: Just finally. People love digital radio. We've seen it with [BBC] 6 Music and we saw the campaign to save 6 Music. We've seen it with the response to Radio 4 Extra. And they'll continue to enjoy it in the future.

Q: I'm sure our postbag and our e-mails will be as big as usual. William Rogers and Ford Ennals, thank you both very much indeed.

...................................

Point of information:

Ford Ennals was chief executive of Digital UK, the TV switchover marketing organisation, from April 2005. He announced his departure in November 2007, the same month that the first UK region entirely switched off analogue television broadcasts.

August 3, 2011

UK listening growth demonstrates radio's strengths in a multi-tasking world

'All radio' listening (1,076m hours per week) is at its highest since 2003. Adult weekly reach is 91.7%. Each listener spends an average 22.6 hours per week with 'radio.' These are impressive numbers. In this respect, it is important to remind ourselves that the RAJAR definition of 'radio' excludes:

'All radio' listening (1,076m hours per week) is at its highest since 2003. Adult weekly reach is 91.7%. Each listener spends an average 22.6 hours per week with 'radio.' These are impressive numbers. In this respect, it is important to remind ourselves that the RAJAR definition of 'radio' excludes:• 'listen again' consumption of broadcast radio (online catch-ups of 'The Archers', for example)

• all podcasts

• listening to pure online radio stations

• listening to online music streaming services or personalised online radio (Last.fm, Spotify, etc).

If these additional 'radio' consumption sources could somehow be added to the RAJAR data, it looks likely that, using a wider definition, 'radio' would be performing at an all-time high. This is not at all surprising in our time-precious, multi-tasking world. Radio proves the perfect aural accompaniment to online social activities, whereas it is nigh impossible to watch television or read a newspaper at the same time as you browse the internet. Radio is a secondary medium – it never monopolises your time.

Commercial radio has benefited from this uplift in total radio listening. Total hours listened to commercial radio (470m per week) have risen from what is beginning to look like a nadir in early 2010.

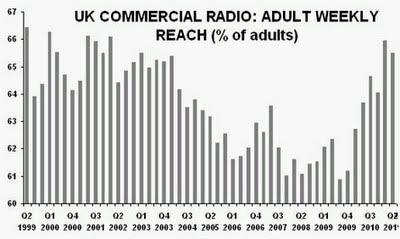

During the last two quarters, commercial radio's adult weekly reach has jumped above the 65% threshold (65.5% in Q2 2011) that had not been breached since 2003.

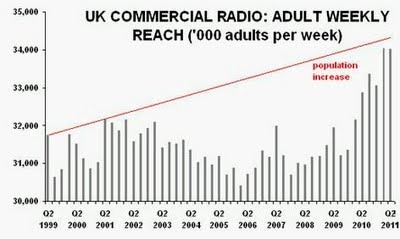

During the last two quarters, commercial radio's adult weekly reach has jumped above the 65% threshold (65.5% in Q2 2011) that had not been breached since 2003. In absolute terms, commercial radio's adult weekly reach has almost caught up with the UK population growth experienced since 1999, rising to 34m in Q2 2011, marginally below its all-time high the previous quarter.

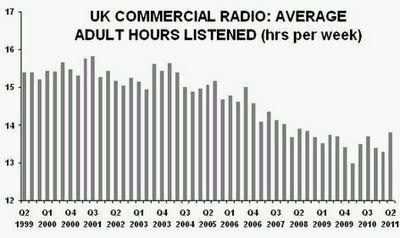

In absolute terms, commercial radio's adult weekly reach has almost caught up with the UK population growth experienced since 1999, rising to 34m in Q2 2011, marginally below its all-time high the previous quarter. The remaining stumbling block for commercial radio is that its average hours consumed per listener remain stubbornly low (13.8 in Q2 2011). As noted previously, young people are spending less time with radio [see blog]. Commercial radio's audence is considerably more youth-orientated than BBC radio, which is why the average length of time for all adults listening to commercial radio remains in the doldrums.

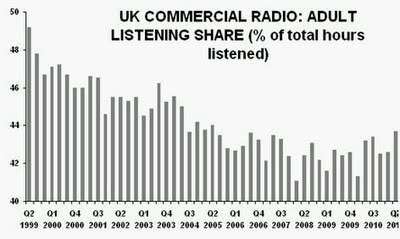

The remaining stumbling block for commercial radio is that its average hours consumed per listener remain stubbornly low (13.8 in Q2 2011). As noted previously, young people are spending less time with radio [see blog]. Commercial radio's audence is considerably more youth-orientated than BBC radio, which is why the average length of time for all adults listening to commercial radio remains in the doldrums. With all this good news for the commercial radio sector, you might imagine that its share of total radio listening had started gaining in leaps and bounds at the expense of the BBC. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The BBC has benefited just as much as commercial radio has from the overall increases in radio listening. As a result, everyone's volumes are 'up' and the share of commercial radio versus BBC radio has remained relatively constant. In Q2 2011, commercial radio's 43.7% share was certainly an improvement on the situation in 2008, when it had looked as if the 40% barrier might be plumbed for the first time.

With all this good news for the commercial radio sector, you might imagine that its share of total radio listening had started gaining in leaps and bounds at the expense of the BBC. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The BBC has benefited just as much as commercial radio has from the overall increases in radio listening. As a result, everyone's volumes are 'up' and the share of commercial radio versus BBC radio has remained relatively constant. In Q2 2011, commercial radio's 43.7% share was certainly an improvement on the situation in 2008, when it had looked as if the 40% barrier might be plumbed for the first time. In fact, the BBC's sustained strength in radio is becoming increasingly understated as more and more 'radio' listening is attributable to 'listen again' on-demand usage and podcasts. The BBC dominates the content available on both these platforms, whilst commercial radio's offerings remain relatively sparse. At present, neither platform is measured within RAJAR. If they were, commercial radio's share would undoubtedly be diminished further.

In fact, the BBC's sustained strength in radio is becoming increasingly understated as more and more 'radio' listening is attributable to 'listen again' on-demand usage and podcasts. The BBC dominates the content available on both these platforms, whilst commercial radio's offerings remain relatively sparse. At present, neither platform is measured within RAJAR. If they were, commercial radio's share would undoubtedly be diminished further.At present, this status quo (using RAJAR's anachronistic definition of 'radio' as purely live and broadcast) suits both parties. The BBC does not wish to be seen to be even more dominant than it already is (54.0% of radio listening in Q2 2011). Commercial radio does not wish to be seen to be weaker than it already is (43.7%) in comparison to the BBC.

And who pays for RAJAR? The BBC and commercial radio. So we are stuck with an old fashioned metric that does not measure radio consumption in the 21st century sense of what we now call 'radio,' but which keeps both its paymasters happy … particularly as neither the BBC nor commercial radio would currently wish to demonstrate publicly the increasing popularity of online 'radio' consumption – which remains the biggest long-term external threat to them both.

July 28, 2011

UK commercial radio sector revenues Q1 2011: local advertising hits 10-year low

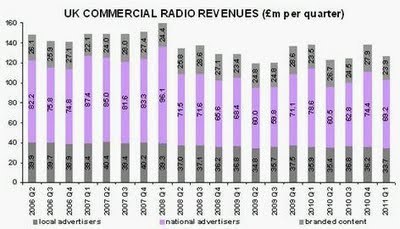

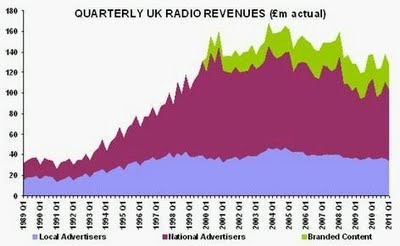

A large part of the problem is the coalition government's swingeing cuts to its marketing budget since May 2010, which have afflicted commercial radio advertising much more significantly than other media [see blog]. Additionally, and very worryingly, in Q1 2011, revenues from local advertisers fell to their lowest level for a decade, even at a time when local radio might be thought to be making client gains from the decimation of the local newspaper industry.

As has been suggested here previously [see blog], the strategy of the largest commercial radio owner, Global Radio, to transform its local stations into 'national' brands would seem to be a recipe for disaster at a time when:

• the national advertising market for radio is shrinking so rapidly (down 34% in real terms between 2004 and 2010)

• the BBC continues to dominate the national radio marketplace with exceptionally well-funded, ubiquitous brands [see blog]

• Ofcom's market research points to overwhelming demand from consumers for more local radio rather than more national radio [see chapter 4(d)]

• many local commercial radio offices have been closed just as local newspapers have closed in many local markets.

TOTAL UK COMMERCIAL RADIO REVENUES:

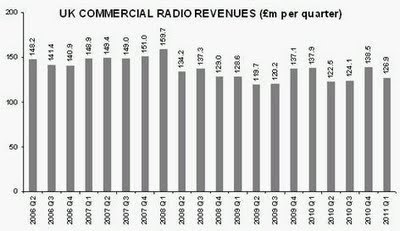

TOTAL UK COMMERCIAL RADIO REVENUES:• Q1 2011: £126.9m (£137.9m in Q1 2010)

• Down 8.0% year-on-year

• First year-on-year decrease since Q3 2009

UK COMMERCIAL RADIO NATIONAL REVENUES:

• Q1 2011: £69.2m (£78.6m in Q1 2010)

• Down 12.0% year-on-year

• First year-on-year decrease since Q3 2009

UK COMMERCIAL RADIO LOCAL REVENUES:

• Q1 2011: £33.7m (£35.9m in Q1 2010)

• Down 6.1% year-on-year

• Lowest quarter since Q1 2001

Although the quarter-on-quarter trend during the last three years appears to be relatively flat, once the data is viewed in the longer term, it is apparent that the commercial radio sector has been unable to grow its revenues back to the peak achieved in 2004. Adjusted for inflation, the 'real' peak occurred in 2000 and, by 2010, commercial radio total revenues had fallen by 33%.

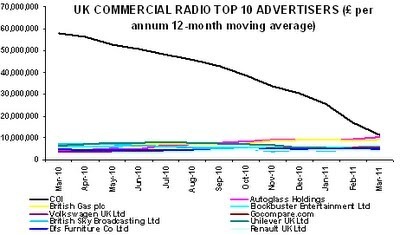

Although the quarter-on-quarter trend during the last three years appears to be relatively flat, once the data is viewed in the longer term, it is apparent that the commercial radio sector has been unable to grow its revenues back to the peak achieved in 2004. Adjusted for inflation, the 'real' peak occurred in 2000 and, by 2010, commercial radio total revenues had fallen by 33%. Following the impact of the 'credit crunch,' the subsequent blow to the sector caused by the government's slashed expenditure on commercial radio advertising from its Central Office of Information [COI] has been catastrophic. COI spend on radio in the twelve months to March 2011 was down 80% year-on-year. In the year to March 2010, the COI had been the radio sector's biggest advertiser by a factor of eight but, only one year later, it had been diminished to almost par with the second biggest radio spender, Autoglass.

Following the impact of the 'credit crunch,' the subsequent blow to the sector caused by the government's slashed expenditure on commercial radio advertising from its Central Office of Information [COI] has been catastrophic. COI spend on radio in the twelve months to March 2011 was down 80% year-on-year. In the year to March 2010, the COI had been the radio sector's biggest advertiser by a factor of eight but, only one year later, it had been diminished to almost par with the second biggest radio spender, Autoglass. In June 2011, the government confirmed that the COI will be axed altogether, offering no respite to the commercial radio sector. According to The Guardian:

In June 2011, the government confirmed that the COI will be axed altogether, offering no respite to the commercial radio sector. According to The Guardian:"Instead the government intends to run advertising and marketing activity out of the Cabinet Office, hiring about 20 extra staff to complement existing communications teams."

With local advertising revenues having hit a decade-low in Q1 2011, and national revenues having fallen 34% in real terms between 2004 and 2010, surely it should be time for commercial radio to ask itself:

• is the current local-station-turned-national-network policy the appropriate strategy for the current advertising market?

• is the current local-station-turned-national-network policy the appropriate strategy to satisfy radio listeners?

• how much longer can the 'slash and burn' strategy (as pursued by GWR, then by GCap, now by Global Radio) be applied to the commercial local radio industry before there is simply nothing left to cut?

• how much more shareholder value can be destroyed in commercial radio before revenues fall faster than costs can be cut?

A question I was asked by one senior radio executive last week was: how will all this commercial radio 'slash and burn' end? I wish I knew. Of one thing I am certain: it must eventually end in tears once the net book values of dozens of commercial radio licences have to be written down by millions of pounds in the accounts of their owners.

This process has already started tentatively:

• Global Radio valued its licences at £333m on 31 March 2010, after having swallowed a £54m 'impairment' write-down in 2008/9

• in 2009/10, the Guardian Media Group suffered an 'impairment' of its radio licences by £64m and now values them at £68m

• Times of India looks likely to have to take as little as £20m for Absolute Radio, a national station it had acquired for £53m only three years ago.

We have to anticipate more write-downs like these.

At some point, even millionaires must not enjoy watching as their radio assets are reduced to dust by shrinking audiences/revenues. But what can be done when those same owners have already starved the goose that had once laid the golden local commercial radio egg?

[Historical data from some previous quarters have been revised marginally at source]

July 23, 2011

Andy Parfitt leaves BBC Radio 1 on a high: separating the man from the myth

At the time Parfitt took on the controller job in March 1998 at Radio 1:

• its share of listening was 9.4%, compared to 8.7% in Q1 2011

• its adult weekly reach was 20%, compared to 23% in Q1 2011

• its average hours per listener per week were 8.1, compared to 7.8 in Q1 2011.

One metric did demonstrate a healthy increase – Radio 1's absolute weekly reach was up from 9.7m adults in Q1 1998 to 11.8m in Q1 2011. However, part of that increase is attributable to the UK adult population having grown by 9% in the interim. Certainly, more adults listen to Radio 1 now than in 1998, but for shorter periods of time, and so the station's share of total radio listening has declined.

Given this impasse to the improvement of Radio 1's ratings, I was surprised to read in the BBC press release announcing Parfitt's departure that:

"Appointed Controller, BBC Radio 1, in March 1998, Andy has led Radio 1 and 1Xtra to record audience figures …"

… and surprised to read Parfitt's boss, Tim Davie, declaring that:

"Andy has been a fantastic Controller and leaves Radio 1 in rude health – with distinctive, high quality programmes and record listening figures …"

The one person still working at Radio 1 who should know for sure that "record audience figures" had not been achieved during the last quarter, last year, the last decade or during Parfitt's entire tenure is Andy Parfitt. Why? Because, between 1993 and 1998, Parfitt had been chief assistant to then Radio 1 controller Matthew Bannister, a turbulent period during which the station's audience was decimated by a misguided set of programme policies that failed miserably to connect with listeners.

The one person still working at Radio 1 who should know for sure that "record audience figures" had not been achieved during the last quarter, last year, the last decade or during Parfitt's entire tenure is Andy Parfitt. Why? Because, between 1993 and 1998, Parfitt had been chief assistant to then Radio 1 controller Matthew Bannister, a turbulent period during which the station's audience was decimated by a misguided set of programme policies that failed miserably to connect with listeners.Between the end of 1992 and March 1998, when Parfitt took over from Bannister (whom the BBC had promoted to director of radio), Radio 1's:

• share of listening fell from 22.4% to 9.4%

• adult weekly reach fell from 36% to 20%

• average hours listened per week fell from 11.8 to 8.1

• absolute adult reach fell from 16.6m to 9.7m.

Radio 1 lost an incredible 58% of its listening, and 7m listeners, within that five-year period, a calamitous disaster from which the station has never recovered [see graph above]. Since then, Parfitt has kept the ship relatively steady, having been appointed in 1998 as a safe pair of BBC hands for Radio 1 after the tragedy of Bannister (who had come from Capital Radio via BBC GLR and had a fantastic track record in news radio, but not in music radio).

Never again will Radio 1 achieve a weekly audience of 17 million adults, as it had done in 1992. Those days are long gone. In recent years, fewer young people are listening to broadcast radio, and they are listening for shorter periods of time. Sadly, radio does not prove as exciting for them as the internet, games or social networking.

Of course, it would have been nice for any incumbent to leave the Radio 1 job on a 'high.' But, unfortunately, it was never going to happen with Parfitt, or probably with any successor. Radio 1's 'golden age' was wilfully destroyed twenty years ago. Nevertheless, somewhere, somebody in the BBC must have decided to invoke the notion of Parfitt's "record audience figures," regardless or not of whether they were a fact.

What surprises me is that every BBC press release must have to pass through endless approvals – within the originating department, in the press office and in the lawyers' office – before it reaches the public. Did nobody out of the dozens of people that must have checked this particular press release ask the simple question: can you substantiate this "record audience figures" claim?

RAJAR radio audience data are publicly available for all to see. Anyone from the BBC could have checked and found that, using every radio listening metric known to man, Radio 1's "record audience figures" were all achieved two decades ago, rather than at any time during Parfitt's tenure. Maybe they didn't check. Or maybe they did, but pressed ahead anyway.

The ability to play fast and loose with numbers and statistics, particularly those that can be said to be at an 'all time high,' might appear to be endemic within the UK radio industry. I have highlighted similar instances of the industry's abuse of statistics in other claims. Now that the consumer press only seems interested in 'radio' stories involving celebrities, and now that the media trade press has been reduced to recycling radio press releases, 'myth' can quite easily be propagated as 'fact.'

I am reminded of a passage in my new book about KISS FM when, two decades ago, I had asked my station boss why an Evening Standard profile of him and his car had featured a vehicle that was not the one he owned or drove.

"It seemed to make a better story," he told me.

July 18, 2011

When is a consultation not a consultation? When Ofcom consults about radio

Ofcom’s consultations on radio are increasingly like that. Ofcom pretends it is going to listen. It doesn’t listen. And then it does whatever it wanted to do in the first place. Mmmm. Surely that is not really a consultation at all.

[image error]

In June 2011, an Ofcom consultation asked six questions about a proposal by Now Digital (owned by radio transmission provider Arqiva) to extend the coverage of its Exeter and Torbay DAB multiplex to North Devon. One of those questions was:

“Q6. Do you consider that there any other grounds on which Ofcom should approve, or not approve, the request from Now Digital? Please explain the reasons for your view.”

However, Ofcom had apparently already decided that its ‘consultation’ was not a genuine consultation at all, when it explained:

“Before deciding whether to agree to Now Digital’s request, Ofcom is legally required to seek representations on the request from any interested parties. … Provided that the request meets the terms of the statute, the decision whether or not to agree to the request is at Ofcom’s discretion.”

So, Ofcom’s 21-page consultation document was really a complete waste of time and money. The decision was already made. And it would be even more of a waste of time and money for anyone to respond. But respond they did.

In July 2011, Ofcom admitted that, out of 234 responses submitted to its consultation, “the vast majority … were opposed to Now Digital’s request.”

Most objected on the grounds that:

• “agreement to the extension of the multiplex would enable the holder of an existing FM local commercial radio licence for Barnstaple to secure the renewal of that licence, precluding the advertisement of a new such licence (which otherwise would have been due to take place forthwith); and;

• the level of coverage of North Devon proposed by Now Digital was unsatisfactory as it would leave 30% of households in the area with no access to radio services in the event of a digital radio switchover.”

[image error]

Did Ofcom care about this volume of public opposition? Not at all. Did it investigate why the share of listening to the merged Heart FM Devon had fallen dramatically to an all-time low last quarter (behind BBC Radio 2, BBC Radio 4, BBC Radio 1 and BBC Radio Devon) [RAJAR, 2011 Q1]? Apparently not. Ofcom explained:

“The [Ofcom Radio Licensing] Committee [RLC] noted the strong opposition to the fact that approval of Now Digital's request would allow Lantern Radio Limited, the holder of the local [Heart] FM commercial radio licence for Barnstaple, to apply for a renewal of the licence and thereby preclude advertisement of a new licence. However, the RLC did not consider that this fact should preclude the granting of Now Digital's request.”

And why not? Because Ofcom’s wholly unrealistic policy objective, for DAB to replace AM/FM radio, is still being doggedly pursued to the exclusion of any wider regulatory issues – consumer choice, market competition or the removal of barriers to sector entry. As well as to the exclusion of the majority of the 234 respondents to this consultation.

To put the same thing in Ofcom’s own weasel words: “What Now Digital Limited sought in its request is provided for in section 54A of the 1996 Act. Agreeing to the request would be consistent with the broad policy aims of that section. Namely, the extension and promotion of local DAB broadcasting with the consumer benefits of greater choice of services.” [emphasis added]

Now Digital promised to launch the first of three new DAB transmitters in North Devon within six months of Ofcom’s approval. And what about the remaining two? Now Digital promised these will be installed “six months after a positive decision in 2013 by Government regarding digital switchover”. Oh, so you mean ‘never.’

The ulterior objective of this proposal was that the promise to build a single new DAB transmitter in North Devon would enable Global Radio to automatically renew its existing FM licence in Barnstaple for a further eight years without a public contest, thus denying any potential new entrants. Ofcom simply rolled over and complied. And what did Ofcom suggest to the complainants who might not have felt that London-based Global Radio was offering them a genuinely local radio station in Heart FM? It stated:

“The RLC recognised the strength of feeling among many respondents to the consultation for there to be an opportunity for an alternative provider of a local radio service in North Devon to apply for a licence … Ofcom is always keen to facilitate new local radio services for listeners where such services are viable and therefore able to offer consumer benefits over the long term. To this end, the RLC noted that, in its response to the consultation, Arqiva stated that there is presently capacity for at least one further new station to be accommodated on the Exeter & Torbay local [DAB] radio multiplex.”

This is patronising rubbish. "Viable"? "Consumer benefits"? Can Ofcom please name any DAB-only radio station that is making an operating profit as a standalone business? No? Because there isn’t one. DAB radio has proven to be one massive financial black hole that has wasted approaching £1bn. Suggesting to consultation respondents that they start their own new local radio station on DAB is akin to Ofcom recommending these correspondents burn down their own houses.

All Ofcom has done is raise two fingers to the people of North Devon in this consultation. If I were Ofcom’s director of radio, Peter Davies, I would not consider booking a holiday in North Devon any time soon.

Unless Global were to return the favour by picking up the tab for his bodyguards?

July 15, 2011

SPAIN: DAB digital radio switched off in most of country

[image error] From 10 June 2011, a new Royal Decree required that DAB broadcasts "must ensure a minimum coverage of 20% of the population," replacing the 50% requirement that had been stipulated in legislation since 1999.

Within the next three years, the government will be able to change this coverage requirement once again if digital radio does not grow its audience share to more than 10% of total radio listening. In the unlikely event that digital radio's audience share ever exceeds 10%, DAB radio coverage will be required to increase from 20% back to 50% of the population.

As reported here in 2010 [see blog], commercial radio in Spain has found no incentive to broadcast on DAB because "the audience is zero." This new legislation relieves broadcasters from having to underwrite an expensive DAB radio transmission system that, to date, had generated no incremental listeners or revenues.

The Decree noted that:

"The development of terrestrial sound broadcasting has been hampered in recent years by, amongst other things, a lack of digital radio receivers which has significantly reduced the audience share initially anticipated and, thus, has jeopardised the possibility for station owners to achieve a return on their investment."

The web site marketing DAB radio in Spain has not been updated since April 2008. The web page for state radio's DAB transmissions no longer exists. It has been reported that DAB radio broadcasts will now be limited to only two metropolitan areas.

[thanks to Eivind Engberg and Wohnort]

July 12, 2011

PORTUGAL: DAB digital radio switched off

RTP explained in a press statement that its decision was the outcome of budgetary constraints and the fact that no commercial broadcasters had agreed to broadcast on DAB. Additionally, it said that "high priced radio receivers had prevented many people acquiring them."

[image error] According to one Portuguese newspaper:

"The DAB terrestrial digital radio system was launched in August 1998 by RTP and by Anacom, which manages the national transmission system. Despite having national coverage, which was decreed by law in July 1998 that permitted broadcasts by all radio stations interested in the platform, DAB never took off in Portugal. Until now, the platform has been limited to relays of existing FM broadcasts by state radio because no commercial radio station signed up. The implementation of DAB also struggled with the fact that there was insufficient supply in the Portuguese market of DAB radio receivers, according to sources consulted by this publication. Apparently, the DAB system was costing €250,000 per annum over more than a decade. The need for RTP to invest in replacing this transmitter network may have weighed heavily on the decision to suspend the service."

GMCS, the Portuguese media regulator, explained in April 2011:

"RTP claims that, despite the significant investment totalling €6.3m to date, the reality is that few Portuguese used the [DAB] system, which leads us to conclude that the allocation of resources to this project does not meet the efficiency requirement and good practice required for public funds."

[thanks to Eivind Engberg and Wohnort]