Grant Goddard's Blog, page 5

March 19, 2024

Mister Soul Of Jamaica … and Thamesmead : 1938-2008 : reggae artist Alton Ellis

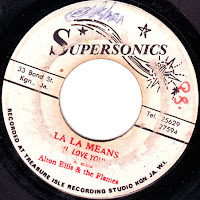

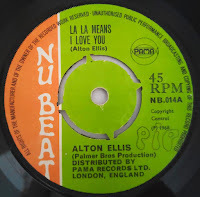

The first record played on the first week’s show of the first reggae music programme on British radio was a single by Alton Ellis, a magnificent singer/songwriter too often overlooked when reggae legends are named. I immediately fell in love with his soulful voice, his perfect pitch and his beautifully clear enunciation, rushing out to buy ‘La La Means I Love You’ [Nu Beat NB014], unaware it was recorded two years earlier. Like many of Ellis’ recordings, this was a cover version of an American soul hit (despite the label’s songwriter credit), though Ellis distinguished himself from contemporaries by also writing his own ‘message’ songs with striking lyrics and memorable hooks. My next single purchases were noteworthy Ellis originals:

‘Lord Deliver Us’ [Gas 161] included an unusual staccato repeated bridge and lines that demonstrated Ellis’ humanitarian pre-occupations, including “Let the naked be clothed, let the blind be led, let the hungry be fed” and “Children, go on to school! Be smarter than your fathers, don’t be a fool!” Its wonderful B-side instrumental starts with a shouted declaration “Well, I am the originator, so you’ve come to copy my tune?” that predates similar statements on many DJ records.

‘Sunday’s Coming’ [Banana BA318] has imaginative chord progressions, a huge choir on its chorus and lyrics “Better get your rice’n’peas, better get your fresh fresh beans’’ that locate it firmly as a Jamaican original rather than an American cover version. Why does it last a mere two minutes thirty seconds? The B-side’s saxophone version demonstrates how ethereal the rhythm track is and shows off the dominant rhythm guitar riff beautifully. It’s a masterclass in music production.

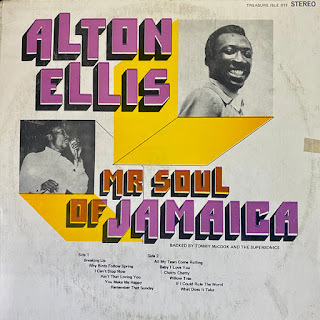

It was only after Ellis had emigrated to Britain in 1973 that a virtual ‘greatest hits’ album of his classic singles produced by Duke Reid was finally released the following year, entitled ‘Mr Soul Of Jamaica’ [Treasure Isle 013]. I recall buying this import LP in Daddy Peckings’ newly opened reggae record shop at 142 Askew Road and loved every track on one of reggae’s most consistently high-quality albums (akin to Marley’s ‘Legend’). It bookended Ellis’ most creative studio partnership in Jamaica when Reid had to retire through ill health.

What was it that made Ellis’ recordings so significant? Primarily, as the album title confirms, it was that his voice uniquely sounded more ‘soul’ than ‘reggae’, occupying the same territory as Jamaica’s ‘Sam & Dave’-like duo ‘The Blues Busters’. I have always harboured the sentiment that, if he had been able to record in America during the 1960’s, Ellis could have been a hugely popular soul singer there. Maybe label owner Duke Reid shared this thought, having recorded ‘soul’ versions of some of Ellis’ biggest songs for inclusion in a 1968 compilation album ‘Soul Music For Sale’ [Treasure Isle LP101/5]. However, at the time, reggae was a completely unknown genre in mainstream America, so Reid’s soul recordings remained unknown there. [The sadly deleted 2003 compilation ‘Work Your Soul’ [Trojan TJDCD069] collected some fascinating soul versions by Reid and other producers.]

Secondly, Ellis’ superb Duke Reid recordings were backed by Treasure Isle studio house band ‘Tommy McCook & the Supersonics’ whose multitude of recordings during the ska, rocksteady and reggae eras on their own and backing so many singers/groups demonstrated a tightness and professionalism that is breathtaking. Using only basic equipment in the studio above Reid’s Bond Street liquor store, engineer Errol Brown produced phenomenal results for the time, operating a ‘quality control’ that belied the release of dozens of recordings every month.

Finally, Ellis’ recordings displayed a microphone technique that was unique in reggae and demonstrated his astute knowledge of studio production techniques. At the end of lines, he would sometimes turn his head away from the microphone whilst singing a note. Because Jamaican studios were not built acoustically ‘dead’, Ellis’ head movement not only translated into his voice trailing off into the distance (like a train pulling away) but also allowed the listener to hear his voice bouncing off the studio walls. ‘Reverberation’ equipment to create this effect technically was used minimally in studios until the 1970’s ‘dub’ era, so Ellis seemed to have improvised manually. Perhaps he had heard this effect on American soul records of the time?

On one of his biggest songs from 1969, ‘Breaking Up Is Hard To Do’ [Treasure Isle 220], you can hear Ellis use this effect during the chorus when he sings the words “everybody knows”, particularly just prior to the fade-out. It is similarly evident on Ellis’ vocal contribution to the brilliant DJ version of the same song, ‘Melinda’ by I-Roy [Crystal A-1112] recorded in 1972.

The same vocal technique is audible on other songs including ‘Girl I’ve Got A Date’ [Treasure Isle DSR1691] in which Ellis elongates the word “tree” into “treeeeee”, as well as “breeze” into “breeeeeeze”, whilst moving his head away from the microphone.

I had always been intrigued by Ellis’ recording technique but had not thought anything more of it until, entirely by accident half a century later, I found startling 1960’s footage recorded at the Sombrero Club on Molynes Road in Half Way Tree, Jamaica. Backed by Byron Lee’s Dragonaires, an uncredited vocal group I presume to be ‘The Blues Busters’ performed their 1964 recording “I Don’t Know” [Island album ILP923] during which one of the duo (Lloyd Campbell or Phillip James) moves his head away from the microphone at the end of lines, similar to what can be heard on Ellis’ recordings.

This started me searching for 1960’s footage of Ellis performing live. Sadly, I found nothing (either solo or in his previous duo with Eddie Parkins as ‘Alton & Eddy’ [sic], similar to ‘The Blues Busters’) to see if he emulated this vocal technique on stage too. For me, it remains amazing that the smallest characteristics audible in a studio recording (particularly from analogue times) can offer so much insight into the ad hoc techniques adopted to overcome the limitations of available technology. The ingenuity of music production in Jamaica during this period was truly remarkable.

Prior to emigration, Ellis had toured Britain in 1967, performing with singer Ken Boothe. Whilst in London, he recorded a single ‘The Message’ [Pama PM707] in which he raps freestyle rather than sings, fifteen years prior to Grandmaster Flash’s hit rap track of the same name, and declares truthfully “I’m the rocksteady king, sir”. Its B-side pokes fun at “English talk” that he must have heard during his visit. The backing music is the clunky Brit reggae of the time, but Ellis’ subject matter is fascinating for its innovation.

1971’s ‘Arise Black Man’ [Aquarius JA single] includes the lyric “From Kingston to Montego, black brothers and sisters, arise black man, take a little step, show them that you can, ‘coz you’ve got the right to show it, you’ve got the right to know it”. The verses and chorus “We don’t need no evidence now” are backed by a big choir. It’s a phenomenal tune despite not even having achieved a UK release at the time.

The same year, ‘Back To Africa’ [Gas GAS164] has the chorus “Goin’ to back to Africa, ‘coz I’m black, goin’ back to Africa, and it’s a fact’ backed by a choir once again. There’s an adlibbed interjection “Gonna stay there, 1999, I gotta get there” that predates Hugh Mundell’s seminal song ‘Africans Must Be Free By 1983’.

Again in 1971, Ellis re-recorded his song ‘Black Man’s Pride’ [Bullet BU466], previously made for producer Coxson Dodd [Coxson JA single], with it’s shocking (at the time) chorus “I was born a loser, because I’m a black man”. The verses are a history lesson in slavery: “We have suffered our whole lives through, doing things that they’re supposed to do, we were beaten ‘til our backs were black and blue” and “I was living in my own land, I was moved because of white men’s plans, now I’m living in a white man’s land”. I consider this phenomenal song the direct antecedent of similarly themed, outspoken recordings by Joe Higgs (‘More Slavery’ [Grounation GROL2021]) and Burning Spear (“Slavery Days” [Fox JA pre]) in 1975. If only Ellis’ song was as well-known as Winston Rodney’s! [In some recorded versions, “loser” was replaced by “winner” and the song retitled ‘Born A Winner’.]

I first discovered Ellis’ song ‘Good Good Loving’ [FAB 165] as the vocal produced by Prince Buster for a DJ track by teenager Little Youth on the 1972 compilation album ‘Chi Chi Run’ [FAB MS8] called ‘Youth Rock’. At the time, I was crazy about this recording, combining a high-pitched youthful talkover with a solid rhythm and Ellis’ trademark voice in the mix. I will be forever mystified as to why the DJ seems to refer to “Cool Version by The Gallows [sic]” in his lyrics!

In 1973, Ellis released the song I never tire of hearing, ‘Truly’ [Pyramid PYR7003], that benefits from such a laid-back rhythm that it feels it could come to an abrupt stop at times. It is one of Ellis’ simplest but most effective songs and has become a staple of reggae ‘lovers’ singers since, employing wonderfully unanticipated chord changes. It sounds like a self-production, even though UK sound system man Lloyd Coxsone’s name is on the label. This should have been a huge hit record!

There are so many more Ellis tracks from this fertile early 1970’s period that make interesting listening, recorded for many different producers and released on different labels. Sadly, no CD or digital compilation has managed to embrace them all. I still live in hope.

After Ellis moved permanently to Britain during his late thirties, he must have struggled in the same way as some of his contemporaries, trying to sustain their careers in the ‘homeland’. Despite UK chart successes, Desmond Dekker, Nicky Thomas, Bob Andy and Jimmy Cliff were very much viewed as one-off ‘novelty’ hitmakers by the mainstream media rather than developing artists. Worse, Ellis had never touched the British charts. Neither did the majority of reggae tracks produced then in British studios sound particularly ‘authentic’ to the music’s audience, let alone the wider ‘pop’ market. Ellis performed at the many reggae clubs around Britain but the rewards must have been limited.

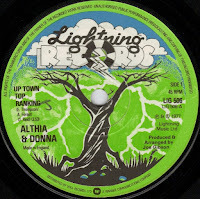

Ellis’ British commercial success came unexpectedly when another ‘novelty’ reggae single shot to number one in the UK charts in 1977. Its story is complicated! The previous year, Ellis’ 1967 song ‘I’m Still In Love With You’ had been covered in Jamaica by singer Marcia Aitken [Joe Gibbs JA pre]. A DJ version by Trinity over the identical rhythm followed called ‘Three Piece Suit’ [Belmont JA pre]. Then two young girls, Althia & Donna, recorded their debut as an ‘answer’ record to Trinity on the same rhythm and called it ‘Uptown Top Ranking’ [Joe Gibbs JA pre]. Other producers released their own ‘answer’ records, rerecording the identical rhythm, all of which could be heard one after the other blaring from minibuses’ sound systems in Jamaica at the time. Unfortunately for Ellis, Jamaica had no songwriting royalty payment system in those days.

I remember first hearing ‘Uptown Top Ranking’ as an import single on John Peel’s ‘BBC Radio One’ evening show. Even once it had been given a UK release [Lightning LIG506], Ellis was still omitted from the songwriting credit by producer Gibbs. Legal action followed and eventually Ellis was rewarded with half of the record’s songwriting royalties (for the music but not the lyrics), a considerable sum for a UK number one hit then. The same track (re-recorded due to producer Joe Gibbs’ intransigence) was then included on an album that Althia & Donna made for Virgin Records the following year [Front Line FL1012] that had global distribution, earning Ellis additional royalties.

Also in 1977, Ellis produced twenty-year-old London singer Janet Kay’s first record, a version of hit soul ballad ‘Lovin’ You’, released on his ‘All Tone’ label [AT006] that, prior to emigration, he had created in Jamaica to release his own productions. Ellis’ soul sensibilities and music production experience inputted directly into the creation of what became known (accidentally) as ‘lovers rock’, a uniquely British sub-genre that perfectly blended soul and reggae into love songs recorded mostly by teenage girls. This ‘underground’ music went on to dominate British reggae clubs and pirate radio stations for the next decade, even pushing Kay’s ‘Silly Games’ to number two in the UK pop singles chart two years later.

Into the 1980’s and 1990’s, Ellis continued to release more UK productions on his label, including a ‘25th Silver Jubilee’ album [All Tone ALT001] in 1984 that revisited nineteen of his biggest hits, celebrating a career that had started in Jamaica as half of the duo in 1959. I recall Ellis visiting ‘Radio Thamesmead’ in 1986, the community cable station where I was employed at the time. He was living on London’s Thamesmead council estate and was interviewed about his label’s latest releases.

On 10 October 2008 at the age of seventy, Ellis died of cancer in Hammersmith Hospital. He had been awarded the Order of Distinction by the Jamaica government in 1994 for his contributions to the island’s music industry. I continue to derive a huge amount of satisfaction from listening to his many recordings dating back to the beginning of the 1960’s and wish he was acknowledged more widely for his outstanding contributions to reggae music.

Now, when I think of Alton Ellis, I recall my daily car commute into work at KISS FM radio, Holloway Road in 1990/1991 with colleague Debbi McNally, us both singing along at the top of our voices with my homemade cassette compilation playing Alton Ellis’ beautiful 1968 rocksteady version of Chuck Jackson’s 1961 song ‘Willow Tree’ [Treasure Isle TI7044].

“Cry not for me, my willow tree … ‘coz I have found the love I’ve searched for.”

March 11, 2024

You can’t tell me what I’m doing wrong… : 1976 : And Mother Makes Four, Camberley

“Why are you choosing a university so far away?” aunt Sheila demanded of me. “You should commute from home to Guildford so you can help your mum.”

I was seething. It was the first time we had spoken in years and THIS was her ‘advice’ to me? How dare she! It was three years since my middle-aged father had walked out on our family to shack up with a runaway teenage bride. Following his departure, he had apparently visited Sheila and poisoned her mind against her younger sister, my mother, so that the pair exchanged not one word for decades thereafter. Just when my mother had needed sisterly support to survive a difficult breakup and resultant hardship, Sheila had frozen her out. But she still felt able to tell me how to run my life?

There had been a time, between 1967 and 1969, when I had walked round to Sheila’s home every afternoon after school. My parents had moved house, now too far away for me to simply catch a bus, so I would wait at Sheila’s between four and six o’clock until one of them arrived after work to pick me up. My lovely older cousin Keith would play me his Jimi Hendrix records on their living room stereogram until the arrival of his father from work at Solartron, a defence contractor in Farnborough. Suddenly, us children would be quickly ushered out into the garden (“Quick! I can hear his car,” Sheila would shout), or the kitchen if it was raining, because taciturn uncle Fred apparently required domestic solitude without the distraction of his three children (plus me). Even as a nine-year old, I viewed this household’s behaviour as bizarrely disciplinarian.

According to my mother, in the early 1950’s her father had forced a pregnant Sheila to marry Fred. That rift evidently never healed. Even by the 1970’s, when the couple and their children gathered with us at our grandparents on family occasions such as Christmas, Fred remained sat in his parked car on the street outside for hours, like a vampire uninvited to cross the threshold. A dozen of us relatives would be sat scoffing our dinner around my grandparents’ old wooden dining table, extended once a year by me pulling out its two extra leaves, while Fred was abandoned outside literally in the cold. It was a family feud that had started before I was born and which everybody since had politely ignored and refused to explain. Ours was a family at (passive aggressive) war.

How dare Sheila lecture me about my education choice! I had already been impacted by my parents having selfishly selected a secondary school at the opposite end of the county, saddling me for seven years with a horrendous commute that took at least two hours daily to journey home. I had been denied a voice in that decision and paid the price, marooned so far from my school that I had not one local friend. Now this was MY time to determine MY future. Besides, nobody in our family had gained a school certificate, let alone attended university. Sheila worked as a ‘dinner lady’ at my former primary school. Upon marriage, Sheila and Fred were offered a post-war semi-detached council house on the Old Dean Estate where they remained their entire lives. I wanted more for my future than that.

When Sheila told me I should stay home to ‘help’ my mother, she had no idea what that ‘help’ had entailed during recent years or the toll it had already taken on my teenage life. As the eldest of three children in a newly single-parent household, I had to be the first to rise every weekday morning and the last to go to bed, usually after midnight. On top of a lengthy school commute requiring bus and train connections, teachers gave two homework subjects to fulfil every weekday night. My mother held down a full-time day job and an evening office cleaning job, requiring me to babysit my two siblings after school, as well as undertake ‘parental’ duties such as teaching my baby sister to read and write, along with hours of play on our living room floor. I thoroughly enjoyed providing her with the attentions that my parents had failed to offer me as a child, but my homework had to remain untouched until she fell asleep. (Daytimes during term time, while my brother and I attended school, our retired maternal grandparents generously looked after my sister at their house.)

The other aspect of my ‘help’ was the task of managing my mother’s financial and legal problems. When household bills and reminders arrived by post, she refused to acknowledge them, preferring to stuff them unopened into a drawer. To her, out of sight literally meant out of mind. I had to organise all her paperwork into folders, challenge incorrect charges, negotiate overdue payments and stave off court appearances and bailiffs. I corresponded with the government’s Inland Revenue tax authority, claimed benefits to which I discovered low-income families were entitled and visited the Post Office fortnightly to cash the ’Family Allowance’ voucher book. The volume of correspondence meant I soon became adept at forging my mother’s signature on letters and forms I prepared.

At the same time, I had to tackle the fallout from my parents’ separation and subsequent divorce. Without consulting me, my mother stupidly had decided, for the division of the couple’s assets, to appoint a local solicitor who had previously been used by my father in his erstwhile property business. The outcome was predictably disastrous. The court awarded her significantly less than half the value of the family home the couple had built themselves brick-by-brick in the mid-1960’s, along with no interest in her husband’s self-employed business in which she had undertaken all the bookkeeping for decades. It rested with me to sit in libraries, searching through legal texts until I could prove her solicitor had failed to adequately represent my mother’s interest. I then made after-school appointments with a brace of legal practices nearby, meeting each puzzled solicitor in my bottle green blazer, until I found one who was prepared to initiate action against a fellow lawyer for breach of Law Society rules.

This was the ‘help’ I had been providing my mother the last three years. Although aunt Sheila had been invisible during that time, her eldest daughter Lynn had volunteered to be fairy godmother to me and my siblings, virtually living at our house, cooking meals and looking after us while our mother worked. I had recently been forced into my first ill-fitting suit to attend her church marriage to a salesman for ‘Smith’s Crisps’ (proud of his company car!). Having no children and no longer working, Lynn became the sensible adult sister our hard-up family had never had and made an immense difference by keeping us alive and together during those difficult times. Her invaluable contribution during our hours of need has never been forgotten.

Aunt Sheila had failed to understand that my reason for going away to university was to reduce the burden on my mother’s precarious finances. At the moment, her earnings were having to pay for my upkeep. My father had been ordered by the court to provide maintenance payments for his children but he was forever in massive arrears. Another of my jobs was to phone Farnham County Court once a month (which necessitated arriving late for school) to remind its clerk that my father’s payments were months’ behind and he needed to be threatened. It was a fruitless task. Worse, on my sixteenth birthday, my cruel father had petitioned the court to reduce my maintenance payments to £1 per annum on the grounds that I should take a job. The stupid court agreed, oblivious of my goal to obtain the education my parents had never had.

I had already made attempts to reduce the financial burden. The local council was now paying for my termly railway season ticket to travel to school (but not for the buses). My mother had always prepared sandwiches for me to take in a Tupperware box for my lunch. To cut this cost, I applied for free school lunches, something I had never eaten before. Eventually the school agreed, I entered the dining room for the first time but the staff forbade me to sit on the benches with my classmates. Instead, I was ordered to sit at a tiny table in the corner of the room with three other boys from lower years (out of a school of 300) who were similarly entitled to ‘free school meals.’ I argued that this policy was discriminatory against us ‘poor’ students. I was told where to go. That became my first and last school dinner. I had to return to taking sandwiches.

Attending university away from home meant that I would receive a ‘full grant’ from Surrey County Council that included my costs of accommodation and travel there and back each term. I realised how expensive living costs would be in London so I had to rule out applying to universities there. That left plenty of institutions across the rest of the country. There would be downsides to moving away. I knew I would miss my family terribly, particularly my little sister whom I had looked after from a baby to become a smart, lively four-year old. There had been a time earlier in her development when she had invented her own non-English words for everything and my presence had been required by our family to ‘translate’ what she meant. My mother had even taken her to the doctor, fearing a speech problem, but she eventually grew out of that habit.

Speaking to me the way she had, aunt Sheila appeared oblivious to our family issues. She was equally oblivious to the fact that universities had to choose YOU, not the other way around. To me, at that time she seemed to inhabit a safe suburban bubble. Whereas, since my father’s departure, our family was being tossed around by circumstance, never certain of what further calamity might arrive around the corner. I could not explain all this to Sheila. I was livid with what she had said but I just walked away. Despite me having had to assume domestic responsibilities beyond my teenage years, she had chosen to address me in such a condescending adult tone. Why did she seem in thrall to my dreadful father who was so eager to make life as difficult as possible for his former family? I never understood.

Once I had completed my first term at university, I bought a Kenwood food mixer for my mother for Christmas, to replace the broken one she had been gifted in the 1950’s and treasured. As a small child, she would offer me its ‘K’ shaped mixing element to lick off the excess cake mix. This was the most expensive present I had given her, having saved up through miserliness with my initial student grant. I was pleased to be contributing financially to our household for the first time, rather than being a financial burden. Now, at the end of each term, I would arrive at my mother’s home and have to spend the first few days answering all the bills, demands and legal threats she had ignored and hidden away during previous months. Somebody had to do it. Sometimes it felt as if my life might never be my own.

These days, on the rare occasion I hear the brilliant number thirteen pop chart hit ‘Captain of Your Ship’ by ‘Reparata & The Delrons’, I am transported back to 1968 when I would sing along with the kitchen radio tuned to ‘BBC Radio One’ in Sheila’s house after school. Good times never seemed so good.

February 27, 2024

Land of a thousand cockroaches : 1986-1987 : Deptford Housing Co-operative, London

“Gimme your money!” he shouted, pointing a pistol at me. He had jumped out from behind some bushes. It was a dark winter evening. I was alone. Nobody was about. I was ten metres from the entrance to New Cross railway station, about to return home, having walked my girlfriend to her train after an evening together. Street lighting beyond the railway was abysmal. I jumped with surprise. It was my first mugging. It was my first year living in London. I was aware of the advice: hand over your wallet and do not argue. I knew the fate of Thomas Wayne.

Except that I had no wallet to give. I had a five-pound note in the left pocket of my black Levi 501’s and some loose change. That was it. No credit cards. In London, I knew to carry as little as possible. I had not carried a wallet since an embarrassing incident in 1978 when I had parked my little yellow Datsun at the end of Upper Gordon Road, opposite Elmhurst Ballet school, and walked into the town centre. Within the hour, I returned to the car and drove home, only to receive a phone call from Camberley police station. Somebody had picked up my wallet from the gutter and handed it in. It must have fallen from the side pocket of my jacket as I stooped to enter the car. I had no idea it was missing. I collected the wallet and found it intact. I have never forgotten that anonymous ‘good Samaritan’. After that, I gave up carrying a wallet.

Later that same year, I had robbed myself through carelessness as a twenty-year old student union vice-president. Following an extensive survey of the photocopier market, having used such machines since the 1960’s, I decided that the Rank Xerox 3600 was the most modern and robust to rent and install on the mezzanine level of the student building in Durham. Once the company’s technicians had set it up and departed, I was so keen to test it that I wanted to make the first copy. However, I had not been carrying any papers so I reached into my pocket and pulled out the only banknote I had. It was £50 because, in the pre-debit card era, I would withdraw £100 monthly from Lloyds Bank’s cash machine opposite Dunelm House. I put the note on the platen, pressed the button and out came a perfect monochrome copy which I then rushed off to let my peers admire. Minutes later, I realised I had left the £50 note in the machine and returned to find it … gone. The copier’s first student user must have been delighted!

Now, accosted in the midst of South London high-rises, within seconds I had to decide how to react. I had no wallet. If I were to offer my meagre five-pound note, this highwayman might become angry and violent. It was never a good idea to argue with a man pointing a gun at you. I stared at my mugger, his face mostly hidden by a blue bandana. He was barely five feet tall. Was he even an adult? 1981’s ‘Stand and Deliver’ music video flickered in my head (no relation). I recalled childhood streets that encompassed Gibbet Lane where, times past, robbers like him on the main road to London had been hanged. I took the rash decision to simply turn and walk away … briskly. I might be shot in the back. I might be attacked from behind. My heart was beating so fast but I knew not to break into a run. And, incredibly luckily, nothing at all happened.

Home was five minutes’ walk away. On the payphone inside the front door, I immediately called 999 to report the incident. While I was sat waiting in the kitchen for a police officer to arrive and take my statement, one of my female co-tenants arrived. I explained breathlessly what had just happened. She quietly recounted that she had suffered the same experience in precisely the same place, a few days previously, and had been relieved of her handbag. Had she reported the robbery? No. I was aghast. Why not? I waited several hours, no police arrived. In the weeks and months that followed, my crime report was never followed up. I lost my faith in ‘the Met’ that night.

What the hell was I doing living in this rundown, sometime scary part of London? It was desperation. In January 1986, I had taken my first job in London, managing a job creation scheme at ‘Radio Thamesmead’. The daily commute by coach and multiple trains from my mother’s home in west Surrey to southeast London was hellish, consuming four to six hours per day. My government pay was too low to afford private rented accommodation in London. Neither could I register for council housing because I was not already dwelling in a London borough. I consulted ‘Yellow Pages’ directories in Camberley library and typed individual letters to every housing co-operative in London, enquiring whether I could rent a room. There was only one encouraging reply, from ‘Deptford Housing Cooperative’, telling me it would contact me when a place became available.

Months passed without a word. I wrote again. I was invited to a meeting. I was eventually offered a three-metre by three-metre room in a ten-person house at a reasonable rent. I took it. My travel-to-work time was cut from hours to minutes and my cost to very little as I was journeying the opposite direction to suburban commuters. The morning trains I was now taking to work were almost empty, whereas I would never forget my first day at Radio Thamesmead when, changing trains at London Bridge station, I had been knocked down the staircase of platform six by a hard briefcase wielded like a battering ram by a descending bowler-hatted gentleman. It had been my first lesson in commuter rage.

Some of my nine new housemates were lovely, some not quite so. Before my arrival, they had jointly decided at a ‘house meeting’ to rent a colour television from ‘Radio Rentals’ but, within weeks, it had disappeared one night from the living room, allegedly stolen and fenced by housemate Knollys. There were characters. One young bearded dropout seemed to model himself on ‘Citizen Smith’, railing against capitalism whilst living on benefits, wearing a denim jacket covered in badges and smoking roll-your-owns. One young woman attended a friend’s Berber wedding in the mountains of Algeria and returned with amazing photos and stories.

My room in the house was thankfully dry and secure, though somewhat noisy as it was adjacent to the railway line. However, I quickly learned never to use the ground-floor kitchen. Switching on the kitchen light triggered a loud sound like the noise of a receding wave washing pebbles down a beach. I learned it was made by cockroaches scuttling to hide from the light, a phenomenon new to me. Not dozens of them. Hundreds! We contacted the housing manager who ordered a pest control specialist to come and fumigate the kitchen. Days later, the noise was still occurring. If you opened any kitchen drawer, you could watch them scatter.

A further visit by pest control was organised. This time, the kitchen and adjoining living room were fumigated simultaneously and cordoned off-limits for a whole day. We were more hopeful. But hope proved not enough to kill the vermin. Within days, the expert had to be recalled to examine our evidence that bugs were still present in massive numbers. He looked. He saw. He told us: “the only way to get rid of them now would be to demolish the building”.

Demolition was not going to happen. Our house was in the middle of a terrace of eight three-story units on Rochdale Way that had only been constructed in 1978. Yet already our unit should have been condemned as unsanitary. But notification to health inspectors would have made all ten of us homeless. Instead, we suffered the bugs and I saw some housemates continue to use the kitchen for preparing meals, despite the evident health risk.

Filth and crime quickly became my initial impressions of London living. When my cassette deck developed a fault, I returned it to the nearest branch of ‘Comet’ in nearby Lewisham which agreed to repair it under guarantee and return it within a fortnight. A month later, I was still waiting. The shop stonewalled me for a few weeks more before admitting that its lorry, with my equipment inside, had been stolen. Would I accept a brand-new replacement? Yes, I would and selected a top-of-the-range model that would substitute perfectly for my vanished bottom-of-the-range purchase.

After having started work in Thamesmead in January 1986, it had taken until September for me to be offered this room in Deptford, six miles away. However, my one-year work contract there ended in December, after which I took a seasonal job at ‘Capital Radio’ in central London. Then, in the new year, I started a long commute three days a week to work at ‘Ace Records’ in Harlesden, twice as far away on the opposite side of the city. Once again, most of my earnings were being spent on travelling to work. I would have saved more money if I could have used my house’s kitchen, rather than having to buy takeaway meals every evening.

It was time to find somewhere to live nearer my new workplace, hopefully a self-contained flat rather than another house share. My one year in Deptford had proven interesting – Deptford High Street market, Pearlie kings and queens, Jamaican patties, second-hand record shops, pirate radio, nearby Greenwich Sunday market – but it would be nice to sleep soundly without worrying whether thousands of cockroaches could climb the staircase overnight to invade my bedroom. I started buying the weekly ‘Willesden Chronicle’ local newspaper from the stand outside Harlesden station to scan the small ads. Presently, my house was not a home.

February 19, 2024

Mining for radio news in an editorial black hole : 2004-2007 : Paul Boon, The Radio Magazine

Magazine editors. What do they do? “They create editorial calendars, develop story ideas, manage writers, edit content and manage the production process…” according to Google. Makes perfect sense. Except sometimes…

Journalism started for me in 1976 when I volunteered for student newspaper ‘Palatinate’ and attended regular meetings under editor George Alagiah who managed a team of section editors, discussed ideas for stories and sub-edited our writing efforts. Subsequently I contributed articles to many publications, including ‘rpm Weekly’, ‘City Limits’, ‘For The Record’, ‘Jazz Express’, ‘Broadcast’, ‘Music Week’, ‘Jocks’, ‘NME’, ‘Now Radio’, ‘Music & Media’ and ‘Radio World’, whose editorial systems worked in much the same way. There was dialogue, there were meetings, story ideas were passed upwards and downwards, teamwork and editorial direction were de rigueur.

In late 2004, lifelong radio industry buddy Bob Tyler called to say he was relinquishing his job as news editor of ‘The Radio Magazine’ and asked if I wanted to take over. I was desperate for paying work, having just returned from a poorly paid freelance contract in Cambodia and then been hung out to dry by ‘BBC World Service Trust’ whose promise of further, more lucrative work never materialised. I had been applying for radio-related job vacancies but none had resulted in an offer. This was the second occasion that Tyler had passed on his editorial jobs to me, for which I remain eternally grateful.

I knew ‘The Radio Magazine’ as the only weekly publication for the UK radio broadcast industry, published as a colour A5 booklet. In May 1986, it had been launched as a scrappy paid-for fanzine named ‘Now Radio’ by Howard Rose, former pirate radio presenter under the aliases Crispian St John and Jay Jackson, filled with gossip and opinion for wireless ‘anoraks’. In October 1992, I had begun to publish a weekly four-page ‘Radio News’ newsletter which I photocopied and distributed for free by mail to a small group of people I thought would be interested, not as a competitor to Rose but complementary since my focus was hard news, information and statistical analysis of ratings.

Unexpectedly, within weeks of my newsletter’s debut, Rose relaunched his fanzine as ‘The Radio Magazine’ with a new layout and new features that looked remarkably similar to mine, such as an events calendar and analysis of ratings. This seemed somewhat coincidental, given his fanzine’s prior six-year, 177-issue history. Any ambition to eventually transform my tiny newsletter into a paid-for magazine had been effectively scuttled, so I persevered for twenty issues before ceasing publication. Unfortunately, ‘good ideas’ prove impossible to copyright and I had already learnt to my cost that the radio industry included people not averse to taking credit for my innovations.

Unexpectedly, within weeks of my newsletter’s debut, Rose relaunched his fanzine as ‘The Radio Magazine’ with a new layout and new features that looked remarkably similar to mine, such as an events calendar and analysis of ratings. This seemed somewhat coincidental, given his fanzine’s prior six-year, 177-issue history. Any ambition to eventually transform my tiny newsletter into a paid-for magazine had been effectively scuttled, so I persevered for twenty issues before ceasing publication. Unfortunately, ‘good ideas’ prove impossible to copyright and I had already learnt to my cost that the radio industry included people not averse to taking credit for my innovations.Nevertheless, twelve years later, I was so desperate for income that the opportunity to write for ‘The Radio Magazine’ had to be accepted. Rose had tragically died in 2002 during routine surgery, bizarrely one week after selling his magazine business to Sir Ray Tindle, a local newspaper and radio station owner. Paul Boon had taken over as managing editor and had employed acquaintance Bob Tyler as news editor until now. Boon was asking me what payment I would require to do the job. I quoted him the National Union of Journalists’ rate per word for contributions to the very smallest publication. He responded by saying he would only pay half that rate. I was disappointed but reluctantly accepted his measly offer, reasoning that some income would prove better than none at all. After all, this job might not last long.

At the outset, I decided upon a financial survival strategy for myself. I would need to spend zero to gather news stories because my expenses were not to be reimbursed. This meant no phone calls, no interviews, no travel to meetings. I would have to depend upon second-hand sources I could cull from the internet, newspapers and magazines. In order to maximise my payments, I would submit as many news stories as I could write, since I was to be paid per word written. Doubtless, the magazine must be receiving dozens of press releases from every organisation connected with the UK radio industry. Naturally, as with my previous magazine work, I anticipated these would be regularly forwarded to me by the editor for a quick rewrite…

Except that they were not. I quickly learnt that no press releases, no news tips, no rumours, no nothing was forwarded to me by the magazine. There were no editorial discussions, no phone calls, no meetings, no guidance, no delegation of work. In fact, nothing at all except the odd emailed complaint about things I had written. I started work in December 2004 but, by New Year, Boon wrote a complaint to my predecessor Bob Tyler:

“I've just had David Bain of CFM on the phone complaining about an out-of-context story with the "wrong perspective" which was printed this week. It was a local press story and as we all know local reporters do not understand radio and in this case printed a story which was not factually correct. We then reprinted, courtesy of Grant the same errors. While I know it has been difficult to contact people at stations over the Christmas period I really think these types of story need to be checked out. We are not in the market of producing overtly partisan stories which demoralise staff at stations. I had a similar call from another station before Christmas.” [sic]

Already, I was baffled as to why ‘The Radio Magazine’ functioned unlike any other publication for which I had worked previously. The managing editor was printing my stories mostly verbatim (fine), sometimes chopping their ends to fit a page (okay), changing my headlines (no problem), but otherwise was only communicating with me by forwarding complaints. Another one arrived in April 2005:

“We have been fending off an irate Simon Horne of Virgin Radio who says the article you wrote (Issue 681) was based upon a mis-quote published in the Scottish Daily Record (or similar paper). Furthermore he is upset that he was not contacted over the story to either check the facts or to give them an opportunity to respond.” [sic]

Surely, this sort of beef should have been with the journalist who had originally quoted the complainant’s words, not with me who had merely extracted the quote from a respected newspaper. Normally, you might expect a managing editor to defend their staff when they had evidently done nothing wrong, but Boon’s reaction in a further email to me was:

“We just cannot let this continue. The Scottish press are notorious for getting facts wrong, heaven knows they have some big axes to grind up there. Time would have allowed for a quick call to the appropriate press officer, Collette [Hillier] can give you a list if you don't have one. Even an email would have given us some support. Virgin are advertisers as well as news fodder, so treating them fairly seems only reasonable.” [sic]

Editorial ‘dialogue’ continued in a similar vein for my entire time as under-resourced news editor of the magazine. Every Monday morning, I emailed as many stories as I could muster, receiving no feedback other than occasional complaints from radio industry personnel who did not approve of what had been published. However, I was submitting so many news stories to maximise my earnings that the magazine regularly added additional pages to print them all, week in, week out…

Except for four issues per year when Boon required no news stories from me because, despite my training in statistics, he insisted upon covering the radio industry’s quarterly audience ratings results. Having collated and analysed radio station data since 1980, I regularly attended the RAJAR organisation’s press conferences announcing its latest numbers at a central London lecture theatre. Boon was present too but did not acknowledge me or seek to collaborate.

Apart from Boon (and Tyler), nobody was aware of my role providing the bulk of ‘The Radio Magazine’s editorial content, as a result of its news stories being published without author bylines. At the time, I was content with this arrangement because I was busy applying for full-time jobs in the radio industry and believed that I was unlikely to be offered employment if it were evident that I was reporting everything that was happening within the sector.

My somewhat distant relationship with the magazine continued until March 2007 when I received an unanticipated email from Boon:

“I am sorry to say I have been forced to bring to a close the freelance arrangement we have with you for news stories. I am sorry. […] On a personal note, I’d like to thank you for the detailed and analytical dimension you have brought to your stories covering the radio industry in these stormy times. My thanks once again.” [sic]

It was the first (and last) occasion I received positive feedback from Boon. By then, I had thankfully found better paid work as a media analyst so the resultant loss of earnings was less consequential. However, this apparent ‘warm glow’ of gratitude vanished almost immediately. Prior to my abrupt dismissal, I had registered for a free press pass to attend a forthcoming radio conference whose organisers then contacted ‘The Radio Magazine’ to rightly confirm my credentials. Boon responded to them bluntly:

“Grant Goddard does not work for this publication.”

I wrote to Boon accusing him of “rudeness” because, instead of simply explaining to the organisers truthfully that, since registration, I was no longer news editor, his words connoted I was a liar. Was he already seeking to erase my substantial and transformational involvement in his magazine during the previous two years? My suspicions were far from allayed by Boon’s response to me:

“I think rudeness is rich coming from you, but that is a separate issue. […] Just chill my friend - life is too short!” [sic]

On that sour note, our email correspondence ended once and for all.

In November 2008, Boon started a job with government regulator Ofcom’s radio licensing division in the same role I had held five years previously. Perhaps he was sat at my former desk. Given that I (and predecessor Bob Tyler) had written 90% of his magazine’s editorial, I pondered whether any number of anonymous “detailed and analytical” news stories published in ‘The Radio Magazine’ might have accidentally fallen into Boon’s journalism portfolio. Any number between zero and the 848 I had written? Those words ‘detailed’ and ‘analytical’ might even have figured in Ofcom’s job description for the role.

During Boon’s subsequent “nine-year stint” at Ofcom, his CV states he was:

“Chapter Editor of the radio & audio chapter of Ofcom’s Communications Market Report an annually published in-depth insight into UK radio and audio developments.” [sic]

My work had once again passed through Boon’s hands! In 2003, as The Radio Authority’s staff member with qualifications in statistics, I had undertaken a mammoth project to create for Ofcom the new regulator’s first historical database combining commercial radio licence, audience and financial information in a group of interlocking Excel spreadsheets. My complex formulae had summarised the state of the UK commercial radio industry for the first time, published in Ofcom’s initial annual ‘Communications Market Report’. But uncredited once again.

'The Communications Market 2004 - Radio' by Ofcom from Grant Goddard[None of the hundreds of issues of ‘The Radio Magazine’ appear online. My news stories for the publication are available to read at https://www.scribd.com/lists/3527224/Radio-broadcasting-industry-news-stories-by-Grant-Goddard ]

February 14, 2024

Some men see things as they are and ask "Why … change?" : 2003 : Neil Stock, Ofcom

A colleague would arrive at my workplace some Mondays with evident cuts and bruises. A tragic case of domestic violence? No. He was a loyal fan of Millwall Football Club, a team characterised by its “historic association with football hooliganism” (Wikipedia). Did I overhear anyone comment that it might be considered inappropriate to work in a government quango when resembling the runner-up from five rounds with Mick McManus? No. Colleagues alleged that this young buck was untouchable because he held finance qualifications that his boss lacked, despite their requirement to legally sign off public accounts. That same boss was then promoted to personnel director, despite having demonstrated to me a similar skills deficit, and then to deputy chief executive of our organisation. Ho hum.

Relevant qualifications and experience appeared to be non-essential for appointment to the management class at The Radio Authority. If you possessed ‘the right stuff’, prior employment in a Norfolk chicken processing factory could prove appropriate for a job regulating Britain’s commercial radio industry. One woman in my small crowded office talked incessantly, inserting expletives into every other sentence. Did any colleague suggest this to be inappropriate behaviour, particularly when some of us were interrogating radio station managers by phone and recording our conversations? No. Once, an interviewee enquired if I was calling from home, having overheard swearing in our office. Er, no, I just work in a madhouse.

Arriving daily to cross the threshold of our office, I felt like one of those unsuspecting visitors knocking on the front door of ‘The Munsters’ home, only to be invited into a scary otherworld that was bafflingly grotesque. Why did I choose to stay there? Because it was the only job I had been offered after countless rejected applications during months of unemployment. And I knew that my private hell would end soon. In several months’ time, the government would be merging several small regulators, including ours, into one new huge one to which staff would be transferred en masse. Well, with the exception of our only two visible minority colleagues, one of whom was dumped in the new regulator’s basement call centre, the other who was told she would have to apply for advertised vacancies despite her lengthy loyal service to our organisation. Which decisionmaker in our midst did we suspect of having never torn up their dogeared ‘NF’ membership card?

In order to prepare us for employment in a modern state-of-the-art regulator, The Radio Authority’s workforce was sent to a government conference centre to watch our new leader, Stephen Carter, talk us through PowerPoint presentations promising us a bright new future. I left these events finally feeling ‘hope’, though some colleagues seemed to sense ‘tyranny’, preferring the security blanket of a dysfunctional abusive ‘family’ already tainted by a corruption scandal exposed on national television. Preferring paperwork to floppy discs, I suspect nobody in The Radio Authority had even needed to press the ‘PowerPoint’ function on their archaic desktop computers. Why should they bother?

Though I had never witnessed our department required to function as any kind of team, we were all sent on a ‘teambuilding’ awayday organised by one of those faceless global management consultancies. We were told to pull together to solve theoretical problems, to play childish games and express our feelings in ‘breakout’ groups. I was paired with a colleague from my office who admitted her early career objective was to work on ‘BBC Radio Four’s ‘Women’s Hour’ programme, though she had never sought training in radio production. My own ‘learning experience’ from that session was something I had observed before – our privately educated elite expect to succeed in their chosen shiny career without needing to put in any graft as practitioners.

I lacked acting abilities, having always volunteered to organise the sound for school plays, but at our awayday I was picked to roleplay a radio licence hopeful whose latest application had been refused, in dialogue with the officer who had turned me down. Having endured enough of that day’s preposterous exercises, I threw myself into this role, choosing to feign a nasal Northern accent and imitate a persistent applicant from Stoke who felt the Radio Authority was discriminating against him. My colleagues laughed loudly at my desperate attempts to win the argument against my posh counterpart. In fact, my performance was art imitating life. I had heard work colleagues often lampoon the speech of a licence applicant from Stoke, despite his experience in radio broadcasting. Naturally, my play-acting did not dent their snobbishness one iota.

I had not understood how convincing my role had been that day until, during The Radio Authority chairman’s monthly walkabouts round our office, he would greet me using the ‘Wayne’ name of the Stoke persona I had adopted … and neither was he being ironic or witty. I had been renamed. I corrected him each month, but he insisted on addressing me on the next occasion as ‘Wayne’. Though he transferred to the new regulator, the majority of our senior management either were not offered jobs there or decided to accept redundancy, I know not which. Given that some had never used a work computer, preferring to order underlings do the grunt work for them, it was difficult to imagine them integrating within a modern office environment.

Everyone in our department received an email requesting our thoughts on how the radio licence application process could be improved. It had been sent by our team deputy Neil Stock, who had surprisingly been promoted by somebody somewhere to lead the radio division within the new regulator a few months hence. I had lots of ‘thoughts’ on the subject so started banging them out on my desktop computer. I was 875 words into my spiel before suddenly halting, asking myself what the hell I was doing providing free insights from hard-bitten experience. Earlier in my working life, I had spent months writing a radio licence application. Stock had never. That application had won up against 39 competitors. I had started working in commercial radio two decades ago. Stock had never. I had launched a London commercial radio station that had attracted a million listeners per week within its first six months. Stock had never. Might he not be harvesting ideas from his ‘team’ to convince his new paymasters that he possessed some kind of grand plan?

This suspicion was confirmed when, not having initially responded to his request, Stock reminded me repeatedly that he still required my contribution. He knew I considered the present application system deficient in almost every aspect because I had told him as much in previous conversations. However, I had nothing to gain from assisting his meteoric rise through the regulatory ranks without commercial radio experience. As is evident from the raw stream of consciousness I wrote then and reproduce (uncorrected) here, my verdict on my employer’s licensing system was damning as a result of having watched it contribute to an increasingly disastrous commercial radio sector in Britain. But criticising The Radio Authority meant criticising my new boss, so I never replied.

Months later, we had moved to the modern office environment of Ofcom. At last, it felt as if I was living in the present century. However, I sat at my desk day after day doing nothing, sidelined by Stock. Eventually he invited me to join his sub-committee tasked with updating the paper licence application form, which seemed like continued attrition to divine my insights. We met a couple of times, during which I retained my counsel about the disastrous system, since it was evident that Stock contemplated only minor amendments rather than a full-blown overhaul. At the end of our final meeting, Stock concluded our discussions by announcing that the application form would remain exactly as it already was, with only the old logo on the front page to be replaced by ‘Ofcom’. I was still working in a madhouse!

One day, everyone in the radio section received an email from Stock requiring their presence at a team meeting, a novelty as no such meetings had occurred at The Radio Authority. We all filed into the glass-walled room in the middle of our floor, waiting to be addressed. I wrote a header in my notebook and expected to jot some bullet points, but what followed left me open-mouthed and unable to note a single word. The sole topic of discussion was these former Radio Authority employees’ refusal to update their working methods to support Ofcom’s modernisation plan. Everyone in the room who spoke supported this strategy. I said nothing as my jaw had already hit the ground. My colleagues were a rabble of anti-revolutionaries. They wanted nothing to change. They were working in Ofcom’s office, drawing salaries from Ofcom, using Ofcom’s resources to hold this meeting … but they wanted to pretend they were still working at The Radio Authority. It was bizarre!

I was reminded of the ‘Luddites’ I had studied for economic history: textile workers in Nottingham who, between 1811 and 1817, had opposed factory owners replacing their labour with machinery. The government had sent 12,000 troops to quell their destruction of new equipment and violence against mill owners, after passing ‘The Frame Breaking Act’ that had made “machine breaking” a capital crime. Two centuries later, I was in the midst of a middle-class penpusher uprising where their disobedience was probably limited to not clearing their desks of papers before sneaking out to catch an early train home. Instead of armed troops, the most violent official response might be a polite e-mail etiquette reminder.

I returned to my desk in a state of disbelief. I must have attended hundreds of meetings during my working life, but that was the first where the consensus was to refuse to adapt to twenty-first century working methods. It felt like ‘Back to The Flintstones’. They would have been happier NOT to have computer terminals on their desks and a fast internet connection. I seemed to be in a minority of one, surrounded in our open-plan office by a couple of dozen paid-up members of the ‘Popular Front for the Liberation of Radio Regulation Reactionaries’. I was half-expecting a singsong of ‘Power to The People’ during our afternoon tea break.

I was SO disappointed. I had endured a miserable eighteen months’ employment at The Radio Authority, during which I had been shouted at repeatedly, told not to talk about ‘radio’, denied my yearend bonus and had failed my annual review on every criterion. Despite my successful track record in radio, I had been treated like a troublesome child. The only thing that had kept me arriving daily for work in Holborn was the hope that the situation at the merged regulator would prove different. Yet, within weeks of Ofcom’s launch, I was witnessing the same crazy behaviours that my colleagues had carried across the Thames with them to recreate their own private Transylvania. Like Harker, I needed to escape the clutches of these vampires if I were to retain my sanity. Could I tie together enough bedsheets?

February 5, 2024

My elderly mother, secret deregulated telecoms entrepreneur? : 2014 : Virgin Mobile

“Just putting you through, dear.” Thousands of calls received each day demanding telephone numbers of businesses and individuals across the country. Shelves of phone directories and ‘Yellow Pages’ for every area of the UK. Banks of phones with operators wearing headsets sat at desks, staring into flickering screens. An impending deal with the Caribbean island of Nevis to ‘offshore’ customer service to a new call centre opened by the country’s premier where staff could be paid as little as £300 per month. My mother was doing all this?

From the early days of telephony, Britain’s ‘directory enquiries’ service had been a successful ‘public service’ available free by dialling ‘192’ to speak with a helpful human being until … Tory government dogma forced privatisation of the country’s phone system in 1984. You can tell Sid that Thatcher’s promise to Britain’s financially illiterate population that they could sit on their sofa and ‘get rich quick’ by merely purchasing a few shares in former public utilities was an outright lie. In 1991, users of ‘192’ started to be charged for the service, despite British taxpayers having contributed billions since 1912 to build the country’s public telegraphy system. Why were we now required to pay shareholders for the privilege of using a service that generations had already paid for?

A Labour government in 2003 opened up the previously singular ‘192’ service to ‘entrepreneurs’ who were permitted to charge an arm and a leg for a brief call to request a phone number. The government regulator did nothing to control this legalised extortion until 2015, by which time there were 200 competing private ‘directory enquiry’ services, all allocated phone numbers that started ‘118’. How on earth were the public expected to choose between so many companies charging varying prices for exactly the same information? What had once been a universal free ‘192’ service had been transformed into a costly logistical nightmare for consumers in the name of ‘market choice’. Unsurprisingly, the number of callers to directory services fell by 38% PER ANNUM after 2014.

Visiting my mother’s home, I saw no signs of a ‘directory enquiries’ start-up business in her tiny terraced house in the Home Counties. In fact, her landline phone rarely rang at all and quarterly bills I received listed few calls. Neither was there space in her postage-stamp back garden for a ’home office’ shed. No computer was visible in the house either because, in the 1980’s, her workplace accounts department’s upgrade from handwritten ledgers to huge concertinaed computer printouts had traumatised her, necessitating me to help interpret and reconcile them on our kitchen table. Despite this overwhelming lack of evidence, nothing could convince Virgin Mobile that my mother was not operating a ‘directory enquiries’ business on her phoneline … whose number happened to begin ‘0118’, as did all landlines in the Reading area. It started like this:

• 6 December 2014 @ 1600. I phoned my mother’s landline on my Virgin Mobile phone, its roaming function enabled, to let her know I had arrived safely in Spain. We spoke for 11 minutes.

• 7 December 2014 @ 2004. I phoned my mother again. We spoke for 3 minutes.

• 9 December 2014 @ 1841. I phoned my mother again. We spoke for 13 minutes.

• 14 December 2014 @ 1708. I phoned my mother again. We spoke for 16 minutes.

I tried to use my mobile phone later that week and found my account had been suspended. I logged in online and was surprised to find that Virgin Mobile believed my maximum monthly credit limit had already been exceeded. The four calls to my mother were bizarrely billed as “Roaming Directory Enquiries” with amounts of £30.15, £9.30, £36.90 and £44.76 respectively (plus VAT at 20%). I had regularly called my mother from abroad, where I usually worked, and never encountered this problem previously. Her phone number had not changed. Evidently, a fault must recently have been introduced into Virgin Mobile’s billing system. I expected it to be quickly fixed once I explained the mistake. For heaven’s sake, who would call a ‘directory enquiries’ number and talk for 16 minutes?

I was so so wrong. I am sufficiently ancient to recall a long-gone era when ‘customer service’ meant listening to a client’s problem and then doing the utmost to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion. I am evidently a dinosaur. Call a helpline now and you might speak with someone in the Philippines whose purpose is to never admit corporate liability for any mistake, to direct you to a non-existent web page and to read a lengthy on-screen script (pre-approved by lawyers) that has zero pertinence to your issue. Having been a customer of Virgin Media for more than a decade, I had already suffered pain trying to get the simplest problems fixed. On one occasion, my wife became so angry with its ‘customer service’ that she had demanded the mobile number of its departmental boss and, phoning it, he answered only to explain he was presently aboard his yacht. How the other half live!

I persevered anyway, phoning Virgin’s customer service to complain twice on 18 December and again on 5 January, calls for which I was charged £12.62 because I was abroad. I was attempting to avoid my impending 6 January invoice being mistakenly inflated. I was lied to, told that my query would be investigated and I would be called back within 24 hours. I was disbelieved, told that I must have forgotten that I had used ‘directory enquiries’ to call my mother, even though her landline is ex-directory. I was fobbed off, told that the issue could not be investigated until Virgin had dispatched my next monthly invoice. I was told I could pay the overcharged amounts immediately so as to restore my credit limit, enabling me to make further calls. I was even told that, because my mother's UK phone number started with '0118', she MUST be a ‘directory enquiries’ service. Remarkably, one customer services person admitted that a previous customer services person I had spoken to had lied to me when having promised to resolve the problem.

Virgin’s invoice arrived and included the overcharges, forcing me to submit an online complaint on 9 January. I received an automated confirmation but no response. I sent the same complaint by letter to Virgin’s complaints department in Swansea. I received no response. I was forced to let Virgin take the £145 overcharge from my bank account or my mobile service would never be resumed.

Now I was unable to call my mother for fear of incurring further crazy charges. Though she had a mobile phone my sister had bought for her, she habitually left it in a drawer uncharged. I added cash to my Skype account but 99% of attempts to call her landline failed as I was told her number did not exist, had been disconnected or was permanently ‘busy’, none of which were true. I had to resort to using phone booths in Spanish internet cafés or calling my sister’s mobile when I knew she was visiting my mother, neither of which enabled frequent communication. To my frail mother, it must have seemed like sudden ‘radio silence’ from her eldest son.

By March 2015, having received no response from Virgin, I registered a formal complaint with ‘CISAS’, the organisation arbitrating customer complaints against Virgin Mobile. In April, it responded that “we have received confirmation from the communications provider that they are settling your claim in full” and it “now has 20 working days to provide you with everything you claimed”. That should have been the end of the four-month affair … except that Virgin Mobile did not pay!

You might imagine CISAS would chase Virgin Mobile for payment on behalf of the customer. You would be wrong. My subsequent correspondence with CISAS to inform that Virgin had still not paid was met with indifference: “We note the points and concerns you have raised and will be contacting the company. We will revert back to you promptly…" Except it never did.

In June 2015, I wrote to CISAS again: “You have failed to “revert back to [me] promptly”, as stated in your correspondence below. It is more than a month since I sent my e-mail to you noting that Virgin Mobile had failed to execute any of the agreed remedies from April 2015. It is more than three months since I submitted my complaint about Virgin Mobile to CISAS. You have failed to address the questions raised in my e-mail of 13 May. I continue to be making expenditures as a direct result of Virgin Mobile failing to remedy the billing problem I initially raised with them in December 2014…”

By July 2015, having received no response, I lodged a complaint about CISAS’ inaction to a related organisation named ‘IDRS’. Although I had been informed in March by CISAS that Virgin Mobile had agreed to settle my claim in full, it appeared that, after refusing to pay, Virgin wished to open up a new attack front on my complaint which it suddenly wanted to pursue to the bitter end. There followed a completely bizarre, intense correspondence in which I had to provide a detailed ‘defence’ to Virgin’s accusations in correspondence with an IDRS employee named “Jean-Marie Sadio BA (Hons) Bsc ( Hons) ACIarb” [sic].

Tellingly, Virgin Mobile now claimed to have sent me a letter dated 10 March 2015 in which it had mentioned the value of compensation I was seeking, a value I had not calculated until nine days later when my complaint to CISAS was submitted. Perhaps Virgin’s litigator had been dozing during Law School lectures, after spending too many evenings viewing ‘Hot Tub Time Machine’. The reason I had never received Virgin’s letter was because it was evidently a work of post factum fiction.

Another of Virgin’s fictions in March was its assurance that it had “take[n] action to prevent future overcharges” when I called my mother’s landline. Strange because a short test call I made to my mother on 4 April 2015 was still charged at the exorbitant ‘directory enquiries’ rate. At any point during this gigantic waste of time, all it needed was for one of Virgin’s thousands of employees to have called my mother’s phone number in order to verify that it was not in fact a ‘directory enquiries’ service. I am certain my mother would have been happy to give the Virgin staffer a forthright piece of her mind, had they requested the phone number of the nearest pizza takeaway.

Happy ending? Later in 2015, I did eventually receive the compensation amount from Virgin Mobile I had been promised in March, but only after this ridiculously long and exhausting struggle. What a way to run a railroad!

However, what was not returned to me was the ability to call my mother’s home phone from my mobile without incurring another massive expense. Skype was still rejecting 99% of my calls to her number, despite attempts every few days. In Spain, the waiting time to install a home landline was more than a year. As a result, between December 2014 and the tragic occasion my mother contracted COVID whilst waiting to be discharged from hospital after a successful minor operation and subsequently died at home in March 2021, my ability to communicate with her from overseas had been reduced to almost zero.

In my mind, Virgin Mobile will forever loom large over the final few years of my mother’s life. In this brave new world where global communication is supposed to have been made so straightforward, nothing can replace the loss of personal contact I suffered during the final stages of my mother’s life. COVID travel restrictions forced my absence during her final months on Earth and at her funeral.

[Correspondence from Virgin, CISAS and IDRS not reproduced here due to long 'confidentiality' warning paragraphs]

January 29, 2024

My thwarted career as teenage reggae music journalist : 1972 : Jamaica

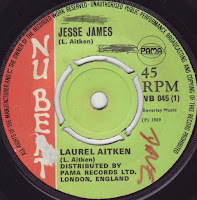

I blame Jesse James. Though cowboys and westerns held zero interest for me, something about the record ‘Jesse James’ appealed, much as an Israeli novelty song ‘Cinderella Rockefella’ the previous year had possessed sufficient charm to become my first ever vinyl single purchase. Months later, having heard this reggae tribute to the outlaw played on ‘BBC Radio One’ or ‘Radio Luxembourg’, I placed my order at the record counter on the first floor of ‘Harveys’ department store in Camberley and, within a fortnight, it arrived. There was no song, merely Laurel Aitken shouting ‘Jesse James rides again’ with gunshot effects over an incessant rhythm. Nevertheless, I had just purchased my first reggae record [Nu Beat NB 045] and I loved it. It was 1969.

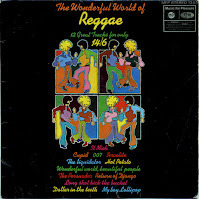

After that, my reggae buying accelerated as fast as pocket money would permit. There was the intriguing instrumental single ‘Dynamic Pressure’ [London American HLJ 10309] recorded at Federal Studio, but so-named as the original had been cut by Byron Lee at his Dynamic Studio. I inexplicably bought the terrible cover version by Brit studio band The Mohawks of ‘Let It Be’ [Supreme SUP 204] for reasons I cannot recall. A recently opened second Camberley record shop in the High Street displayed a rotating stand of reggae albums from which I bought ‘The Wonderful World of Reggae’ [Music for Pleasure MFP 1355] because it cost only 14/6 for twelve tracks. I had been unaware it actually comprised (half-decent) cover versions by London session musicians of recent reggae songs heard on the radio.

In 1970, I bought several reggae singles that had reached the UK charts, including ‘Young Gifted and Black’ [Harry J HJ 6605], ‘Montego Bay’ [Trojan TR 7791] and ‘Black Pearl [Trojan TR 7790], all of which I was to discover later were cover versions of American songs. During this era prior to Jamaican sound engineers’ creation of ‘dub’, most B-sides were straight instrumental ‘versions’ of their A-sides. However, it was the occasional exceptions that offered my earliest insight into the remarkable creativity and fresh ideas issuing from Jamaica’s (and London’s) recording studios:

The B-side of ‘You Can Get If You Really Want It’ [Trojan TR 7777], a straight cover of Jimmy Cliff’s song, was a Desmond Dekker original ‘Perseverance’ with great lyrics over an amazingly fast rhythm track that came to unexpected abrupt halts. I still love it more than the A-side.

The B-side of ‘Leaving Rome’ [Trojan TR 7774], an exceptionally haunting instrumental laced with strings, was another instrumental ‘In the Nude’ with trumpet player Jo Jo Bennett double-tracked improvising over an urgent rhythm. This must have been the first ‘jazz’ recording I had heard and I loved it.

The B-side of ‘Rain’ [Trojan TR 7814], a cover of the Jose Feliciano song, had ‘Geronimo’ wrongly credited to singer Bruce Ruffin but consisted of a man shouting ‘Geronimo’ and ‘hit it’, echoed over a rhythm I later learned was by UK band The Pyramids. It was bizarre but fascinating.

Most significant was the B-side of ‘Love of The Common People’ [Trojan TR 7750], another cover version with a string arrangement overdubbed in the UK by ‘BBC Radio 2’ doyen Johnny Arthy’s orchestra. The instrumental ‘Compass’, credited to producer Joe Gibbs’ studio band ‘The Destroyers’, could not have been more different than the unrelated smooth A-side. It literally changed my life. Essentially it was a jazzy solo saxophone workout, but over an instrumental track drastically different from anything I had ever heard. The walking bass was turned up loud but had been deliberately dropped out of the mix on occasions. The continuous rhythm track had been filtered to leave only its high frequencies and then echo added, making the result impossible to determine which instruments were playing. The whole thing was bathed in enough reverb to sound as if was recorded in a bathroom.

For me, ‘Compass’ was a really radical production, emphasising the bassline and using studio effects to contort other instruments into sounds that were unrecognisable and ethereal. The sound engineer (likely Winston ‘Niney’ Holness at Gibbs’ studio in Duhaney Park, Kingston) had transformed a typical reggae rhythm track recorded (for an unrecognisable song) onto four-track tape into something completely different and incredibly creative, using only a standard mixing desk and some basic electronic effects. It was the first example I had heard of a ‘mix’ that had not tried to reproduce musical instruments as they sounded naturally, but to have deliberately distorted them into unnatural noises that created a whole new audio experience. It was the first track I had heard that stripped a recording down to so few elements: a pumping bass, a bizarre ultra-tinny ‘clop-clop’ rhythm and a booming saxophone. ‘Compass’ was a harbinger of ‘drum and bass’ mixes which reggae would soon pioneer (the first occasion I saw this term used was the B-side of Big Youth’s 1973 single ‘Dock of The Bay’ [Downtown DT 497]).

More than anything, it was ‘Compass’ that hooked me onto reggae at the age of twelve. I played that B-side at home hundreds of times but was desperate to hear more recordings like it. Not easy when you live thirty miles outside of London. Instead, my reggae research started in earnest. From the ‘Recordwise’ record shop owned by Adam Gibbs opposite my school in Egham, I collected weekly new singles release pamphlets distributed to retailers and stared longingly at the many titles of new reggae releases, more of which were issued in the UK during this period than all other music genres added together. I joined the shop’s ‘record library’ which loaned vinyl albums to customers for a fortnight for a small charge. I soon ‘worked’ in that shop during lunchtimes as my knowledge about popular music was becoming encyclopaedic. But, above all, I became obsessive about reggae.

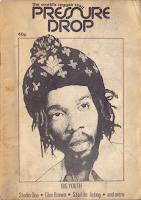

I wrote to ‘Trojan Records’, one of London’s two major reggae distributors, requesting information and was invited to join the newly created ‘Trojan Appreciation Society’ run by two female fans. For my subscription fee, I received monthly Roneo-ed newsletters, some free records and a huge gold metal medallion imprinted with the company’s logo attached to an imitation gold chain, which I wore to school every day under my white school shirt and striped tie for the next five years … until the gold paint had worn off on my chest. I had a fold-out double-sided A2 sheet of all Trojan’s past releases, listed by each of its myriad of weird and wonderful record labels, which I would peruse in awe for hours. I so wanted to hear all this wonderful music, but how?

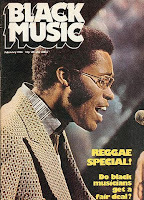

My luck was in. I was already an avid fan of ‘BBC Radio London’ when it launched Britain’s first ever reggae radio show, ‘Reggae Time’ hosted by Steve Barnard on Sunday lunchtimes. To the chagrin of my mother’s attempts to serve our family’s Sunday dinner, I would sit listening with headphones plugged into our hi-fi system, cataloguing a list of every record played each week from the very first show, recording songs onto cassettes. It was my much-needed window into the world of reggae and enabled me to enjoy almost two hours of new releases weekly, interviews with artists and dates of sound system events (inevitably all in London). Doing my homework on weekday nights, I would listen to my cassettes over and over again until I knew the songs by heart. From then, my pocket money was used to buy less well-known reggae records beyond those in the charts and played on mainstream radio. My personal reggae ‘wants list’ inevitably grew longer and longer.

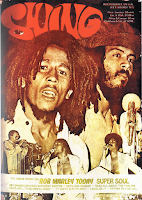

Somehow, I discovered the existence of a music and entertainment magazine published in Jamaica named ‘Swing’. I may have finally identified its address in an international publishing directory in the local library, sending them cash for a subscription and henceforth received monthly copies by air mail. Along with interviews and features, it published advertisements for record shops and record labels in Jamaica, offering a first-hand insight into the island’s reggae industry. I devoured each A4 colour issue and treasured them like valuable artifacts.