Grant Goddard's Blog, page 7

October 2, 2023

Radio is my bomb? : 2003 : the DAB digital radio customer complaint hotline, The Radio Authority

The Bomb Squad arrived in vans, ran into the Holborn office block and up its staircase to the eighth floor. We watched events unfold from the car park below, the assembly point to which our organisation of forty-odd people had been evacuated an hour earlier.

That humdrum morning had been interrupted by a large cardboard box delivered by Royal Mail to our office. It was not particularly heavy but had lots of stamps on the outside with a ‘Belfast’ postmark. If you were a celebrity or public figure whose opinions were widely distributed, you might anticipate threats would occasionally be made against your life. If you had a desk job in a little-known British government quango, your greatest work challenge might normally be choosing where to lunch. However, that morning, the box’s addressee Soo Williams was taking no chances. The emergency services were called.

Eventually, the ‘suspicious package’ was removed by ordnance experts and exploded elsewhere. It was found to contain nothing but paper. Printed petitions signed by hundreds of Belfast citizens demanding that religious community radio stations be licensed locally. Williams’ name had been written on the box due to her recent promotion by The Radio Authority to manage the launch of ‘community radio’. Returning to our desks after the false alarm, I ruminated what those god-fearing citizens who had toiled to gather so many signatures might have thought of having been suspected by the recipient of being terrorists.

That morning’s event exemplified the disconnect between the regulator of the radio industry and the public it was supposed to serve. Someone with an interest in the UK community radio movement would have known that tiny unlicensed radio stations had existed for years on both sides of the Irish border, broadcasting church services and information to their communities. Indeed, one history argues that the Catholic Church in Ireland was “the world’s largest pirate radio operator”. However, few of The Radio Authority’s desk-bound administrators demonstrated interest in the medium they were employed to regulate. I was the only employee to have worked in a community radio station (licensed in a 1970’s experiment), having been a founder member of the Community Radio Association two decades previously. But now, within this dysfunctional workplace, I was regarded as the office junior … at the age of forty-four.

Back at my desk, I returned to taking regular phone calls from members of the public dissatisfied with the new-fangled DAB ‘digital radio’ receiver they had just purchased. I never quite understood why the switchboard regularly passed such calls to me, as I bore no responsibility for DAB radio, and my colleagues in the Development office suffered no such impositions. It was already self-evident to me that the rollout of this new radio technology had been disastrous for listeners, though I was expected to defend the system, and worse … to blame the listener for its inadequacies.

Staff were issued with a ‘helpful’ sheet of topics to raise with complainants about DAB. Suggestions to be made to members of the public experiencing difficulties tuning into stations on their new receiver included:

move your radio nearer a windowlisten to the radio in an upstairs roomyour residence might be constructed of the wrong materialsyour residence might be located in a valleyyour residence might be located in a dense urban areayour residence might be in an apartment block or a basementyou may need to install a rooftop antenna.Many callers were understandably baffled and annoyed by these ‘answers’ to their problems, proffering a torrent of abuse or hanging up. Many had spent around £90 on a portable DAB receiver and expected it to deliver what the industry’s marketing had promised – ‘crystal clear’ reception of a wide choice of radio stations. The most popular receiver, the ‘Pure Evoke-1’, had been designed to be portable and had no socket to even attach the suggested external antenna, let alone the connectivity to update and improve its software. And why did it resemble a wooden post-war radio in an era when connected mobile phones were looking increasingly futuristic?

One of my callers’ commonest gripes was the result of DAB radios having been marketed and sold nationwide, even though many parts of Britain had yet to be connected to the DAB transmission system. In this instance, all I could suggest was that the consumer return their receiver to the shop and demand a refund because no digital stations were yet audible locally. I too shared this problem because, although The Radio Authority had denied me its Christmas cash bonus in 2002, I had received the DAB radio gifted to all staff. It remained in its box as I was living in Brighton, where DAB transmissions had yet to arrive.

The root of the dissatisfaction with DAB radio was not the technology itself, which had been a smart European innovation, but the way it had been implemented by Britain. Those critical roll-out decisions had been made by people like the ones in my workplace: administrators who had no experience working within the radio industry, encouraged by technologists keen to promote anything ‘digital’ with an evangelical fervour, oblivious as to whether consumer demand was evident. At the top of this unholy group of conspirators were government civil servants who mistakenly believed that Britain and British industry could dominate global markets by adopting a technological standard in which the rest of the world had shown scant interest. Meetings of this cabal seem to have merely intensified their cult-like determination.

The stumbling block their paper plan faced was the disinterest of the commercial radio industry itself which, at that time, was profitable and had expressed no dissatisfaction with its existing, robust FM radio transmission system. When The Radio Authority advertised the first national DAB multiplex licence in 1988, it faced the very real possibility that no radio companies would submit bids. To avoid this embarrassment, the regulator had to ‘strongarm’ Britain’s largest radio group into making the only application. GWR Group plc’s then chief executive Ralph Bernard later admitted:

“GWR was encouraged to apply for the national [digital] licence, and was under some pressure to invest in the opportunities for a national licence from the then regulator [The Radio Authority]. Had we not done it, there would be no national DAB platform now. Not only that, [the regulator] did not know what they would have done on the question of national radio stations with regard to the opportunities given by the then government to renew their national licences for a further period of time if they were to commit to going digital. But how can you [do that] if there are no opportunities to go digital because there is no national multiplex? When I put that question to The Radio Authority, I was told that the answer was: ‘We don’t know what would happen – there is no Plan B’. It was just an assumption that someone would go for [the national DAB multiplex].”

“When we were seduced into believing that this was going to be the only [national digital] licence, we realised that there would be substantial losses, but the payback would be when you have the opportunity to be the only player in the national market for DAB. When it’s The Radio Authority, an agency of government, you tend to believe what you are told. On that basis, the investment was justified and, at the time, getting it through my Board was not easy.”

Having rescued the regulator from potential embarrassment in its ill-judged pursuit of the DAB dream, Bernard naturally now held some sway over The Radio Authority and its decisions. There evidently did exist such a thing as a free lunch for its senior managers when Bernard would invite them to The Ivy restaurant in anticipation of outcomes coincidentally beneficial to his business. On two occasions at the regulator, my actions threw a spanner into this cosy relationship and I suffered consequences (written up here and here) from my bosses, despite me having acted in what I believed was the public’s interest. I learnt to my professional cost that I was supposed to be a ‘civil servant’ to commercial interests, not to our citizens.

How did the story end for commercial radio? Badly. GWR Group plc’s subsequent merger with Capital Radio Group plc, both profitable public companies prior to their investment in DAB, proved a financial disaster, their DAB assets were divested for a song, an offshore investor acquired the merged business and Bernard exited the industry. This tragedy was repeated in the lower echelons of the radio business when the entire UK commercial radio industry had to be rescued by private investors. Most local radio stations that had existed since the 1970’s were replaced by national ‘brands’. Local content all but disappeared. Thousands of radio professionals lost their jobs.

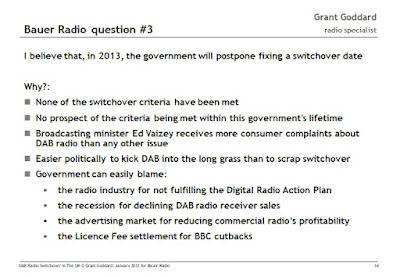

How did the story end for DAB radio? Even worse. In a presentation I was commissioned to make to the board of the second largest radio group in 2012, I predicted that the government would kick the much heralded ‘digital radio switchover’ date into the long grass. I was pooh-poohed by the company’s technologists at the meeting, but my predictions came to pass … while theirs turned to dust. Naturally, I was never invited back. British commercial radio’s enormous investment in the disastrous DAB platform impoverished the entire sector, reducing it to little more than a jukebox music service for listeners who lacked Spotify accounts.

The deluded dream finally died in 2016 when ‘Pure Digital’, the ‘great white hope’ of British designed DAB radio receivers (though manufactured in China), was sold to Austrian company Aventure AB for £2.6m, following its £7.9m loss during 2015/6 as a result of declining receiver sales.

With the advantage of hindsight, the entire DAB debacle now seemed like a rehearsal for the similar self-harm caused by Brexit a decade later. Men in suits with little or no experience of working in the real world of commerce pursued a fever dream regardless of its practicality, oblivious to its outcomes but buoyed by their mistaken sense of superiority. Their project was to foist a uniquely ‘British’ solution on the population that would purposefully diverge the UK from the rest of the world (British DAB radios would not even function in France). Their words and documents were stuffed with misinformation and downright lies that supposedly supported their theories. Without their posh accents, they could have been mistaken for used car dealers.

Despite the wilful destruction of the commercial radio sector’s economic value, talent, creativity and public service that they had fomented, many of Britain’s DAB ‘protagonists’ went on to be lauded with industry awards, honours and lucrative jobs. For anyone who followed the Brexit disaster, it will sound like all too familiar a story.

September 25, 2023

The trophy son : 1969 : Charles Church & IMIC Properties Limited, Camberley

It was the summer of ’69. My father had insisted I accompany him to his meeting. He had driven us to a wooden gateway on the south side of Lightwater Road that led into fenced farmland. He pulled in, parked our Rambler station wagon on the roadside where, on that warm sunny morning, the man we had come to meet was already waiting. My father introduced himself and then me:

“This is my son, Grant, who will be starting at Strode’s School in September.”

My father had heard stories about this local man and his wife having bought a house, moved in, then repaired, modernised it in contemporary style and furnished it stylishly before selling it a year later at a handsome profit. They had then repeated this process … twice. The strategy Americans call ‘flipping’ was unknown in Britain at the time, but this story had fascinated my parents during recent years, being a practical route to amass capital when mortgages were difficult to obtain for self-employed professionals. My parents might have enthusiastically copied this tactic, had they not already two school-age children. Finally, my father had requested an initial meeting with Charles Church.

In 1965, Australian state-owned airline Qantas had bought twenty plots of land in Camberley out of more than 200 for sale that had formed the grounds of Copped Hall, the estate of retired Captain Vivien Loyd. Between the Wars, in a small factory on Frimley Road, he had manufactured tanks sold to twenty foreign armies, as well as an ultralight plane known as ‘The Flying Flea’. Loyd even produced an engine-powered lawnmower called ‘The Motor Sickle’ that was exhibited at the 1950 Smithfield Show. Qantas built modern detached houses with large gardens in a generously landscaped development named ‘Copped Hall Estate’ intended for occupation by its pilots flying from Heathrow Airport, a twenty-mile drive away. However, for reasons unknown, its houses were never used.

One of these properties, at 18 Green Hill Road, served as the location for the 1969 film ‘Three Into Two Won’t Go’ directed by (Sir) Peter Hall, starring Rod Steiger and Claire Bloom. Scenes of the street showed overgrown front gardens of empty houses on this ‘ghost’ estate, seemingly ideal for a movie shoot. Except that filming was disturbed by noise from tanks driving around the Ministry of Defence’s vast 18-hectare wooded, hilly tank testing ground a mere hundred yards away on the other side of ‘The Maultway’ main road, a legacy of Captain Loyd’s enterprise. Sandwiched between Camberley and Lightwater, the land is still used for this purpose but is now shared with local dogwalkers and bikers.

Eventually, Qantas decided to appoint a local estate agent to try and sell its unused houses, despite their location on the periphery of Camberley, three miles from its town centre and lacking a regular bus service. This was an ideal opportunity for Church and his wife to purchase one, and then another, to transform them into more marketable homes with ‘all mod cons’ that were demanded during the 1960’s. We lived three-quarters of a mile away from the entrance to this estate, on the opposite side of Upper Chobham Road, enabling my curious parents to observe goings-on there.

Church had been born more than a decade after my father and was very smart, having attended grammar school and studied civil engineering at university before starting his first construction contracting business, Burke & Church, in 1965. My father’s background could not have been more different, having left school at age fourteen and taken an apprenticeship with Redland Cement in Bracknell. He had studied quantity surveying at ‘night school’ and eventually started his own home-based business, producing drawings for renovations and extensions to local houses, offices and factories. By 1967, he had created ‘Architectural Drawing Services Limited’ in a small Camberley High Street office where he had ‘graduated’ to designing entire buildings. His business stationery appended the initials ‘AFS, ARIBA’ to his name even though he held no architectural qualification.

What Church and my father did have in common was that both had been building their first houses, both unusually modern for Camberley, simultaneously in 1967. Both had wives who were intimately involved in their businesses. Both aspired to modern interior designs. Indeed, I seemed to have spent much of my childhood sat on Heals of Tottenham Court Road’s wooden rear staircase that curled around one of those old ‘cage’ lifts, awaiting my parents to finish their endless perusal of state-of-the-art furniture. The two men’s skills were complimentary. Church knew how to build houses. My father knew how to design them.

So why had I been dragged along to the pair’s initial meeting? It was because my father lacked the formal education of Church but was desperate to portray himself as an equal. I had passed the ‘Eleven Plus’ examination that summer though my parents had decided not to send me to Camberley Grammar School, located opposite the infant and junior schools I had attended the last six years and the obvious, most local choice. Instead, I was to be sent to a grammar school in Egham that required a two-mile journey from our house to Camberley station, followed by a thirty-minute train ride. I was offered no say in their decision. Why was my school journey about to be made so arduous for the next seven years? Because Church too had attended Strode’s School and my father had waited to arrange this meeting until my parallel future there had been secured.

In addition to his design skills, my father could prove helpful to Church because he had amassed significant experience over the years ensuring his renovation designs were approved by the local council’s planning committee. He had joined ‘The Camberley Society’ and was attending their monthly meetings to hobnob with the local ‘great & good’, much to the disdain of my mother. Somewhere in his life, my father had adopted a neutral middle-class accent which, along with his smart suits, seemed sufficient proof to convince people he was indeed an ‘architect’. His speech contrasted starkly with that of his older brother who spoke like a character from ‘East Enders’, though success in the building industry had rewarded him with a detached house in Farnborough that had separate in and out driveways. On the handful of occasions I accompanied my father to visit his brother, I was sent up to his daughter Janet’s room, the first person I met who attended a private school. Although the same age, we had absolutely nothing in common.

After that summer’s initial introduction, Church and his wife Susanna became regular visitors to our bungalow which my father had designed and built in a Frank Lloyd Wright style with much glass and bare brickwork. The two couples became friends and my father set up a company to formalise their partnership. I was told to find a suitable name. I leafed through my copies of ‘Billboard’ magazine, the voluminous American weekly music industry publication I bought from a newsstand on the corner of Oxford Street and Regent Street whenever we visited London. I spied an advertisement for the International Music Industries Conference organised in Cannes (forerunner of ‘MIDEM’) which was abbreviated to ‘IMIC’. The company was to be named ‘IMIC Properties Limited’.

Houses were designed. Houses were built. Houses were sold. Profits were shared. My father bought an American Motors Javelin sports car. Both he and Church started flying lessons separately at nearby Blackbushe Airport. I accompanied my father on one occasion and hated the experience. Nevertheless, it remained my task to regularly test my father’s knowledge necessary to obtain his pilot licence, which is the reason I can recite the NATO phonetic alphabet to this day. For a short while, life was good.

In 1971, our family started to fall apart. My mother had terrible bruises on her face and the toilet door of our house had been kicked in as a result of my father’s temper. By 1972, he had left us for good. After an entire childhood having been required to work in his business, providing skills in mathematics, finance and administration that he lacked, I no longer wanted to even talk to him. He responded by making his family’s life as difficult as possible, stealing back every gift he had ever bought us, starving us of funds and dispossessing me and my baby sister.

Evidently, my father’s business partnership with Church must have disintegrated at around the same time though, to their credit, both he and his wife maintained contact with my mother, offering her support and practical assistance. Charles Church Developments Limited was launched by the couple in 1972 and became one of Britain’s most successful housebuilding enterprises. IMIC Properties Limited was forcibly dissolved in 1980. By then, my father had disappeared, owing thousands in unpaid court-ordered maintenance to our family. He was eventually found by US Immigration to be living illegally in Arkansas and deported. His debts to us were never paid.

On 1 July 1989, at the age of forty-four, Charles Church was killed when, after broadcasting a mayday call, the Spitfire [G-MKVC] he had restored crash landed near Blackbushe Airport. By then, he was reportedly one of the richest two-hundred people in Britain with a fortune of £140m. My mother attended his funeral. It was a tragic conclusion to the beginnings of an exciting business opportunity for my father that I had witnessed at that roadside rendezvous two decades previously … but which had ultimately impoverished the rest of our family.

September 18, 2023

If you go down to the lemon groves today, you’re sure of a big surprise : 2017 : Mar Menor, Spain

The motionless car stood sideways across the road with its four doors wide open. A road accident? Moving nearer, nobody was visible either in the car or on the roadway. The engine was running and its headlights were bright, but there was no sign of another vehicle or an obstruction the car could have hit. If not a traffic accident, then what had happened?

I was taking my daily early morning run, normally uneventful, along a straight, flat tarmacked ‘agricultural road’ that led three kilometres out of the Spanish village as far as the shore of the Mar Menor inland sea. When the summer heat became this oppressive, runs proved feasible only during the darkest hour just before dawn. Other than an occasional farmer on his tractor, the roads were empty at that time of day as village life did not awaken until ten o’clock. Something about the car up ahead of me was definitely not right.

Wherever I found myself in the world, my morning constitutional involved an outdoor run. This exercise regime had been thwarted only in Moscow where, after several attempts, I was choked by engine fumes and endangered by cars driven along pavements; and in Cambodia where even a short walk in its humid heat immersed you in a sauna-like furnace. I had started running regularly forty years ago as a university student to relieve stress, initially circling the little used 400-metre Maiden Castle racetrack alongside the River Wear a few times, then having built up my regime daily until it reached dozens of laps.

At school, a weekly three-mile cross-country run had felt akin to punishment during Wednesday afternoon ‘Games’ in winter for the thirty of us disinterested in playing team football. Regardless of what the weather might throw at us, PE teacher Graham Taylor would send us out on the footpath up Coopers Hill, passing the John F Kennedy Memorial, the site of the Runnymede signing and Langham Pond, to return to our school Playing Fields more than an hour later. For a cheap thrill at the outset, boys would hold hands in a line and the end one touch the electrified fence alongside the A30 Egham By-Pass, awaiting the periodic pulse that sent a shock through each of us in turn. I am grateful to Taylor for having unwittingly initiated my fitness regime, despite his indifference in the face of my disdain for competitive sport. When I visited his office on my final school day after seven years to purchase a yellow ‘Strode’s’ sweatshirt, he scoffed: “Why would you want that now?” I still have it almost half a century later!

Not that I was wearing it in Spain that morning as, even before dawn, it was already way too hot. As I ran closer towards the car in the darkness, I could see it positioned across the roadway to shine its headlights into the neat rows of the unfenced lemon groves that stretched for miles on both sides. I was close enough now to make out that the car’s back seat and passenger seat were piled high with … lemons. Aha! Even Clouseau would have deduced that I had stumbled across a lemon thief operating under cover of darkness in the middle of nowhere. Despite my temptation to stick around and view the perpetrator, I had no desire to be shot at dawn. Instead, I ran on into the darkness, reached my end-point where sunrise was emerging over the sea, paused and returned along the same route to find the thief long gone as daylight was starting to seep across the landscape.

Friday was ‘street market day’ along the village’s ‘High Street’ where, that week, I spotted a stall with a man selling loose lemons, rather than those from marked agricultural crates. Was he the fruit bandit whose nocturnal handiwork I had witnessed? I never knew and, apparently, neither did the pair of municipal police who ambled through the market. It was an example of the combination of audacity and pettiness apparent in Spain. In the centre of another village, already I had watched an old woman nonchalantly rip out plants from a municipal flowerbed in broad daylight and carry them home, apparently unconcerned who might be watching. Do the Spanish even have a word for ‘shame’?

During another early morning run on the same route, I was surprised to find a woman’s matching check bra and knickers on the ground at the edge of the lemon grove in the middle of nowhere. My initial instinct was to leave the road and walk into the grove to convince myself this was not a horrific crime scene. Then I realised it might not be construed as civic duty for the police to find me possibly standing over the remains of one of the five thousand women murdered annually in Spain. So, yet again, I simply ran on … after photographing the evidence.

The only regular sign of life I saw on my route out of the village during daily runs was a group of men who stood outside the ‘Sport Bar’ at six in the morning on weekdays. They would await the arrival of minivans whose drivers shouted out the number of men required for that day’s work in the surrounding fields. As I passed the group, they would jeer and shout at me as if the notion of an old man running in order to maintain his health was a completely alien concept to them … which in rural Spain it probably was.

There was a memorable morning when, following their usual taunts, one man emerged from the crowd and started to run alongside me. I was not intimidated. I imagined he might continue a short distance, tire quickly and return to his mates. However, once we reached the limit of the village’s lit streets, he continued into the darkness of the lemon grove. Now I began to feel intimidated, particularly as he insisted on running so close beside me that our elbows touched, despite the unlit road being sufficiently wide for two vehicles. If I were to stop running, or to say anything, I was worried that he might turn on me, so I continued and ignored him.

After a while, he switched to running behind me, but so close that I could feel his breath on the back of my neck. It was a stupid and dangerous move, as he could have easily tripped me up, so I responded by picking up my pace to pull away. This must have been misunderstood as a challenge rather than self-preservation, as he caught up, then ran closely beside me once again, then switched to running inches in front of me. If I had maintained my speed, I would have been in danger of stepping on his heels and tripping up both of us. I slowed my pace and watched as he continued to run on ahead into the darkness beyond. He must have felt so proud that day to brag to his mates how, during a quarter-hour, he had run faster than a foreigner three times his age. Angry and upset, I cut short my usual routine, turned around and re-entered the village on a longer route to avoid the ‘Sport Bar’. After that, I ensured that my morning run never passed there again.

Even everyday village life proved a challenge. Each occasion my wife and I shopped in its supermarket, we would be the only customers in the checkout queue humiliated by having to empty out the contents of our knapsack and handbag. We observed locals in its aisles pocket items from shelves with apparent impunity because it seemed self-evident that only foreigners were thieves. We also aroused ire because we paid by debit card, which the checkout person would insist on grabbing from us, inspecting this strange technology and ramming it into a prehistoric machine that only functioned sporadically and required a wait of several minutes to display ‘approved’.

Having spied a poster for an ‘open day’ at the village’s modern theatre building, we thought it would make an interesting diversion. However, before our visit inside had even reached the auditorium, we were confronted by an angry group of women who ordered us out of their building. Many such municipal projects become ‘white elephants’ created by the mayor’s ego simply to impress his chums and the electorate, regardless of practicality or cost. Belonging to neither category, we were evidently not welcome. From its published schedule, this particular theatre only staged productions on about a dozen days per year.

To make explicit this village’s unfriendliness to outsiders, it would have been an easy task to simply stick two huge posters on the outside of their building that state in big red lettering ‘DO NOT ENTER FOR NO MEMBER OF THE SOCIAL CLUB’ in English. That is exactly what the village’s social centre had done to ensure that no foreign tourist dared to cross its threshold, pointedly warning in a language we found no local spoke.

Scuttling back to our rented terraced house near the village centre, we were left to the mercy of our neighbours. On one side was a couple in their fifties who argued and watched television late at maximum volume. Friday evenings, a minibus would arrive to unload a group of primary school age children into their tiny house. Group sing-songs at high volume ensued … continuously. In pyjamas, I knocked on their front door at two o’clock in the morning to ask politely if the tuneless singing could be curtailed. The door was slammed in my face. At three o’clock, I knocked again as the noise had continued regardless. Nobody answered. Their ‘party’ ended at dawn. By afternoon, the minibus would return and take away the children. Some kind of cult?

The first we knew of our opposite neighbour’s business was our living room filling with smoke from an unidentifiable non-tobacco drug. I traced it to the electricity meter on the party wall, built so thinly that smoke from next door seeped through holes made for cables connecting the adjoining houses. Thick insulation tape had to be purchased to block the gaps around the meter and prevent us suffering involuntary highs. Noises from this neighbour’s kitchen, audible through the wafer-thin wall, sounded as if he was chopping vegetables all afternoon … but then it continued through the night. Eventually it dawned on us that he was a drug dealer cutting up supplies for customers. Why else would he drive a black sports car with gold wheel rims, darkened windows and a windscreen inscribed ‘PSAddicted’ that was parked out front? Not the kind of delinquent with whom to raise a neighbourly complaint, even though we often passed him sat outside on his front doorstep during daylight, openly smoking drugs.

One day there was a flurry of activity outside his house, including a brief visit from a local policeman. Later, a smartly dressed, middle aged man arrived and we could hear loud discussions inside the house surprisingly in French, a language never previously heard there. We could make out the lawyer instructing the dealer that he had a stark choice: negotiate with the family of the young girl he had hit while driving his car outside the local school and pay them an amount sufficiently persuasive to drop a prosecution; or flee to his native North Africa. We did not stick around long enough to learn of Kid Charlemagne’s fate.

Had we been staying in Sodom or Gomorrah? God may not have inflicted a plague of locusts on this village but he had dispatched its inhabitants a stern warning by infesting the whole place, not just the odd house, with cockroaches. You could exit your home in the heat of the noonday sun and see large bugs scuttling up the exterior walls and along the streets, totally oblivious to daylight or humans. Because household drains had been constructed without U-bends, the vermin could travel with ease through the sewers into buildings. Everything that we witnessed there resembled a biblical tableau … of a godforsaken village that was determinedly stuck in feudal times.

September 11, 2023

Baby, we were bored to death : 2000 : FM radio station market, Toronto

Why does Toronto have such insipid and boring radio? Our city is vibrant, artistic, culturally diverse and entertaining, so why is none of that reflected in our uninspired radio stations? Travelling in Europe and North America as a radio consultant, I listen to a lot of radio and it is tragic to concede that my own city has some of the most boring radio stations known to mankind.

Opportunities to change this sad state of radio in our city are everywhere, but have too often been ignored. When Shaw Communications purchased 'Energy 108' a couple of years ago, it could have reinvented the station as a cultural focus for Toronto's young people. Instead, Shaw fired 'Energy's most knowledgeable DJ's, introduced Sarah McLachlan songs once an hour (in a dance music format?) and changed the name to … 'Energy 107.9'. Wow! How many minutes did it take the marketing department to devise a strategy that unambitious?

Rogers Media's purchase of 'KISS 92' last year was a complete no-brainer. Can you name any other city of similar size in North America that has had no Top Forty radio station for a period of even a few months? And yet Toronto suffered this malaise for several years. Even if Rogers had hired a helium-voiced bimbo DJ to front a Top Forty format, it still could have captured a huge audience hungry for what used to be called 'pop music'. And that is exactly what they did. 'KISS's ratings are noteworthy, not just for the hordes of spotty grade nine students who naturally gravitate towards Backstreet Boys soundalikes and terrible Canadian techno. But the station's substantial audience over the age of twenty is a sad reflection of the lack of any other remotely exciting music station in Toronto. For those of us past our teen years, 'KISS 92' at least makes you feel good to be alive, compared with other FM music stations that treat listeners like senile geriatrics with one foot already in the grave.

One would hope that 'KISS 92's runaway success might encourage its competitors to try and become a little more imaginative in their programs. The signs so far are not particularly encouraging. 'EZ Rock 97' revamped its daytime line-up last week to introduce even more soporific DJ's and has changed its slogan from 'My Music At Work' to 'Soft Rock Favourites'. Station owner Telemedia appointed a new Program Director drafted from its Calgary operation to oversee these changes. Yes, Calgary – that hotbed of radical, imaginative radio formats! 'EZ Rock' looks certain to retain its nickname of 'Radio Slumberland' in our household.

Milestone Radio, scheduled to launch next year, has an incredible opportunity to turn its black music format into an exciting, inclusive station that could electrify the city. After all, black culture has never been so predominant, nor so imitated, in mainstream music and arts. With imagination, Milestone could be a very successful radio version of 'City TV'. Whether its owners can grasp that challenge, let alone succeed with it, depends upon the station's ability to overcome three obstacles. Milestone's programming plans are the obvious product of committee debate, with too many worthy (but commercially disastrous) ideas generated by individuals who have particular axes to grind. Its recent effort to recruit a Program Director in the US rings alarm bells that Milestone is creating a cookie-cutter US-style urban music station that would reflect nothing of Toronto (listen to 'WBLK' for days on end and you will learn absolutely nothing about Buffalo, but everything about 'strong songs'). And lastly, the spectre of minority shareholder Standard Broadcasting might be waiting quietly in the shadows for Milestone's ambitious plans to fail in the first year, so that it can take control and resurrect the station as a smooth-jazz format, fitting perfectly alongside its mind-numbing 'MIX 99'.

As for 'Edge 102' and 'Q-107', their owners should have been bold enough to extinguish these dinosaur formats years ago. There is so much exciting new music in the world, but you will certainly never hear any of it played on these two stations. The malaise is so bad that Toronto radio critic Marc Weisblott felt obliged to apologise in a recent column (radiodigest.com) for spending so much time listening to New York City radio via the internet. No need to apologise, Marc. Our only ray of hope is that one fine morning, some bold senior executive in Shaw/Corus, Standard, CHUM or Rogers might suddenly understand that radio which is stimulating and challenging can also be a commercial success. I would prescribe that executive a quick radio listening visit to any major city in the world to understand the potential. Otherwise, Toronto radio is condemned to be a mere revenue-generating asset designed to send us all to permanent sleep with yet another Celine Dion or Bryan Adams song.

[Submitted to Toronto weekly what’s on paper, unpublished]

September 4, 2023

Flying home for Christmas … eventually : 1995 : Sheremetyevo Airport, Moscow

“Ground staff have told me our plane is four inches too close to the gate,” the pilot announced in a tone midway between bewilderment and exasperation. “I have had to order a tow truck which will attach to the aircraft to pull it backwards, so I apologise that it will be some time before we can all disembark.”

‘Some time’ turned out to be more than an hour, during which all us passengers could do was wriggle in our seats and wait it out. The British Airways flight from London had passed uneventfully until then. However, once in airspace beyond the former Berlin Wall, absolutely anything could happen … and often did. Foreigners’ time and money proved irresistible commodities dangling like low fruit on a tree labelled ‘FLEECE ME’ that offered easy pickings for ‘communist’ opportunists who post-Glasnost had metamorphosed into ‘biznessmen’.

Welcome to Moscow! If it looks like a metropolis, is busy like a metropolis and makes the noise of a metropolis, then it must be a … but looks are deceiving. Moscow resembled one of those Wild West film sets constructed years ago in the deserts of Spain and Italy where convincing Main Street facades hide the vacuum of an absent third dimension. Some apparatchik in the Kremlin’s Department for Urban Construction must have been ordered by their Great Leader to build Russian cities just like ones he had viewed in ‘King Kong’, without either of them having ever set foot inside an American skyscraper … or airport. From the outside, everything might look normal, but nothing inside actually functioned correctly.

British Airways flights into Moscow transported a mix of world weary ‘road warriors’ who destressed holdups like this by finalising PowerPoint presentations on their laptops, and rich Russians who could afford the luxury of avoiding the discomfort and safety record of their national airline. Whilst the former passengers travelled light, all the better to avoid border guard interrogations, the latter boarded with clutches of overflowing shopping bags stamped with logos of the most expensive shops in Knightsbridge and Bond Street. Cabin crew had apparently given up informing such ‘frequent oligarch flyers’ that their voluminous purchases should be packed into a suitcase for storage in an overhead locker. Those unlucky enough to be seated next to a fur-coat clad, Gucci/Prada clotheshorse made you feel like an impoverished Bob Cratchit half-hidden at the back of a seasonal Harrods shopwindow display.

Without hesitation, Sheremetyevo is the worst airport I have ever encountered. Even Mombasa’s departure ‘lounge’, where you sit cross-legged on hot tarmac under an open canopy, comes a distant second place. During my years shuffling between radio stations owned by Metromedia International Inc at eight locations within five countries, I took an average two flights per week, routed through various European airports, but was required to visit Moscow more frequently than other destinations. Unfortunately. Most airports at least attempt to ensure their travellers’ journeys are as frictionless as possible, whereas Sheremetyevo’s apparent priority objective dreamt up within some arcane Five Year Plan was to inflict as much pain as possible on its customers.

I soon realised that around half a day had to be anticipated just to navigate the few hundred metres between deboarding the plane and the airport exit … on a good day! There were no queues organised for passengers to pass through the twin hurdles of passport control and customs checks, merely a sea of hundreds of people tightly packed into an open concourse, all jostling to exit. Some Russians simply pushed through the crowd to the front. Nobody chastised them. In Russia, those who had the power used it … ruthlessly. Nobody said a word. We all stood in silence, crushed by those around us, some smelling of vodka or BO. Russians pretended you did not exist as they trod on your foot or elbowed you out the way. Sometimes it could take three hours to be pushed along to the front.

To keep my claustrophobia at bay whilst trapped in this sea of inhumanity, I would stare upwards at the arrival hall’s high ceiling. It offered no comfort. The entire roof space had been covered with thousands of identical sliced aluminium tubes to create a vast honeycomb pattern. However, any artistic pleasure from this aesthetic was overshadowed by my observation that several of the tubes were missing. This discovery created a further phobia that, were another of those metal tubes to fall from that significant height onto the waiting crowd, its acceleration would result in serious injury for anyone below. Life in Russia was precarious at the ‘best’ of times, but death by sub-standard Russian glue smeared onto an airport ceiling was not what I wanted on my Death Certificate.

Eventually exiting the terminal building, an awaiting Metromedia driver would always enquire why it had taken me so long to appear, as if he imagined I must have been dawdling for hours in the Duty Free or supping cocktails in the airport bar. If only! All I wanted was to be somewhere where I was not surrounded by an impatient crowd who you feared might shoot you dead if you so much as acknowledged their presence or made eye contact. This ‘airport run’ was the only guaranteed occasion that Metromedia would provide me with a driver because there existed no navigable public transport or marked taxis to travel the 29km route to the city centre, and aggressive freelance drivers accosting travellers outside the terminal were, at best, likely to rob you or, at worst, dump your body in a ditch.

My visits to Moscow would last weeks or months at a time. Every day was stressful, not because of my work, but because the environment was so dangerous and unpredictable. One of my American work colleagues was arrested on a Moscow street and thrown in jail overnight for doing … nothing. Drivers were randomly stopped by uniformed men, often pretending to be officials in cars equipped with flashing blue lights, in order to extract bribes or on-the-spot ‘fines’. Even walking along a city street was unsafe because some vehicles used the pavement to accelerate around traffic jams or red traffic lights. Laws, if they existed at all, were routinely flouted with impunity.

In 1995, I was determined to reach home by Christmas, having booked a British Airways flight from Moscow to London for the morning of 20th December. At the airport, finding it was delayed, I sat in the departure lounge’s transparent plastic walled ‘waiting room’ and plugged my laptop into the power socket to finish some last-minute work tasks. Within minutes, a security guard entered the room, admonished me aggressively for stealing electricity and confiscated my UK/Russia plug adapter. You learnt to bite your tongue in these regular confrontations where exertion of ‘power’ demonstrated neither logic nor reason. Eventually the flight was called, so we handed in our handwritten exit visa forms and walked to the gate. Hours passed. No plane appeared. We were herded to the bar area where we were offered one free drink.

Many more hours passed. By now, it was dark outside and snowing. A British Airways person appeared and finally admitted that the flight had been cancelled for reasons unknown. We were to stay overnight in a hotel and board a replacement flight the following morning. However, before then, three challenges remained. We were herded to a baggage area where we were confronted with a mountain of suitcases from which we had to identify and recover our luggage without assistance or checks. Then we had to wait at immigration control where the day’s exit stamp in our passport had to be identified and cancelled with, you guessed it, a further rubber stamp over the top. Finally, we were confronted with a table on which a cardboard box had been placed, in which had been dumped all our exit visa forms. Without assistance, passengers had to sift through this pile of papers to find their own document to take it back for reuse tomorrow. Only then could we exit the airport.

I had no understanding of where we were meant to be going. I simply followed the person in front of me out of the terminal where I could see a long line of people dragging suitcases, snaking along an uphill pathway in the pitch black, the snow and the minus fifteen temperature. It was a ten-minute trudge until we reached the assigned hotel where, being British, we queued politely at the reception desk for room keys. By now, it was eleven at night and we had wasted twelve hours at the airport, where we had only been offered one drink each. I rang room service and ordered a pizza from the menu which I was told would arrive within thirty minutes. It did not. I rang room service again, only to be told that my order had not been fulfilled because British Airways passengers were not entitled to hotel food. By then, I had discovered that neither were we allowed to make international phone calls from the room’s phone, so our loved ones would have no idea why we had not already arrived home. Gggggggrrrrrrrr! At midnight, tired and hungry, I fell into bed in my clothes as it required too much effort to open and partially unpack my suitcase.

The following morning, we were finally allowed to eat for free from the hotel breakfast buffet bar. In the light of day, we all looked crumpled and exhausted by the interminable wait for a flight that had yet to materialise. Assembled together in the lobby, we were eventually led back out into the snow to snake our way down the narrow pathway to the airport, dragging our luggage. Humiliatingly, we had to repeat all the airport processing formalities already endured the previous day: check-in, luggage weighing, passport control, submission of yesterday’s visa form and customs checks. Would the plane even arrive as promised? Some of us voiced fears that an airport ‘Groundhog Day’ might strand us here through the holidays. Thankfully, the promised plane arrived at the gate, we applauded it with relief and, by the time we were seated on board, it felt as if we were half-way to British firmament. There was much relief when we finally arrived at Heathrow in time for Christmas.

Of the many times I passed through Moscow airport, there was only one occasion that could be called positive. I had coincidentally been booked onto the same incoming flight as an American senior Metromedia executive. The corporate travel department must have assumed that we both warranted some kind of ‘VIP’ service, despite me being a lowly European contractor. Immediately after exiting the plane at Sheremetyevo, we found officials holding up cards with each of our names who took us aside from the other passengers. Led along a separate corridor, we were taken to a large empty room where we were told to sit on huge throne-like chairs around its perimeter. Each of our flight’s handful of VIP’s was assigned an official who took our passport and completed entry visa. After only ten minutes, he returned with our suitcases and our passport that had been stamped appropriately without us even having been interviewed. As we were whisked away swiftly to the terminal exit, I tried to calculate how many dozen occasions I had wasted an additional two or three hours in the midst of the madding crowd just to escape this airport. How the other one percent lives!

August 28, 2023

Don’t play that song for me : 2004 : unusual FM radio formats, Phnom Penh

Here in Phnom Penh, there are seventeen radio stations on the FM dial, even though Cambodia’s capital city has a population of less than a million. But you are more likely to hear a song by Britney Spears or Madonna on the 'BBC World Service' (100 FM here) than on any of the local FM stations. Only one, 'Love FM' 97.5, plays Western music and its playlist stretches solely from the obscure ('Pretty Boy' seems to be the most requested song) to the bizarre (New Kids On The Block?). The rest of the local stations play exclusively Cambodian music. It’s radio, Jim, but not as we know it. Several hundred hours of radio listening suggest two Cambodian programme formats that could be adopted in the West:

KARAOKE CALL-IN RADIO

Most stations in Phnom Penh have a daily show or two of karaoke call-in. Each station employs a pair of singers (one male, one female) who sit in the radio studio with a standard karaoke CD machine plugged into the mixing desk. Listeners call in to a mobile phone number which is also routed to the desk. Most stations have no Telephone Balance Units or 'clean feed' system, so callers can only hear the presenter by keeping the volume of their radio turned up, which leads to howling feedback (considered normal here) during every call. Stations with Optimod-style audio processing suffer ever worse feedback loops.

There is no pre-screening of callers. There is no delay system. You hear the mobile phone ring in the studio. The presenters answer the phone on-air, ask the caller’s name, where they are calling from, and the song they wish to sing. While one presenter finds and cues the appropriate karaoke CD, the other chats amiably with the caller about the reasons they have chosen the particular song. The song starts, one of seemingly hundreds of Cambodian love songs that are all male/female duets. If the caller is female, the station singer sings the male verses, and prompts the caller to sing the female verses. If the caller is male, the reverse applies.

The karaoke machine adds echo to the singer’s voice. It is no exaggeration to say that most callers have no sense of either melody or rhythm. The majority are absolutely appalling singers and seem to have no sense of shame exhibiting their complete lack of ability on-air. Conversely, all the radio station singers are excellent, not only at singing but also at treating every caller with dignity and respect. Each caller is allowed to complete their selected song, despite their obvious lack of talent, the howling feedback and the poor-quality audio (most callers use analogue mobile phones). At the end of the song, the presenters thank the caller and, as soon as they end one call, you hear the mobile phone ring again, and they move immediately to the next caller.

Because there is no pre-screening, some callers inevitably are put directly on-air who want a different radio programme, a different radio station, or the local pizza delivery service. The presenters treat even the mistaken callers with the same respect. Each karaoke show continues in this fashion for several hours, punctuated only by batches of hideous commercials, each lasting two minutes and using more voice echo than the average King Tubby dub plate. At the end of the show, the two station singers get to sing a song together, without the humiliation of having to duet with an out-of-tune, out-of-sync caller bathed in feedback.

GRIEVANCE DROP-IN RADIO

In a country where the legal system rarely delivers results that resemble natural justice, the majority of the population look elsewhere for ways to resolve their problems. What better medium than a radio station? At the same time, in a country where the news agenda is dominated by ruling politicians’ pre-occupations, what content can journalists safely use to fill time in their news bulletins? The answer for both the people and the journalists is to air relatively minor grievances from the population that in no way threaten the government’s rule.

For state radio, this means sending journalists to distant provinces to interview farmers about agricultural problems or minor disputes with their neighbours. The results are passed off on-air as 'news'. Imagine if 'You & Yours' replaced the 'Today' programme on 'BBC Radio Four'. In Phnom Penh, where hard-pressed commercial radio stations can barely afford to employ journalists, some stations sympathetic to opposition parties operate an open-lobby system. Citizens who have grievances to air simply turn up at the radio station, their complaint is recorded, and then broadcast unedited and without context. The results are startling for a Westerner accustomed to hearing only carefully produced 'packages' of balanced opinions or only short sound bites of real people’s voices emanating from cosy UK radio stations.

This week I heard a woman sobbing and moaning her way through an unedited ten-minute monologue, explaining how her husband had allegedly been abducted by a criminal gang and disappeared. Last week, on another station, I heard a widow sobbing uncontrollably and threatening to set fire to herself and her children because ownership of the radio station belonging to her dead husband had just been awarded to another man by the municipal court. Both broadcasts moved me to tears, despite being in a language I cannot understand. Why? Because I cannot remember hearing such raw emotion spilling out of my radio set (except in drama) for a very long time.

The majority of our phone-in shows have become carefully packaged entertainment while our grievances seem trivial compared to the tribulations suffered by people here. Because the majority in Cambodia still have no access to a telephone, the radio station drop-in provides an important forum for aggrieved citizens to voice their anger and emotion. Listening to these raw, unedited voices has reminded me of the potential emotional power embodied in the radio medium, and the need for programme producers back home to play less safe, allowing more real voices on the radio that can move listeners to tears.

------

After several more months on this diet of karaoke and tear-jerking stories, I anticipate that my return home to a menu of 'BBC Radio One' and 'Capital FM' will quickly reveal such 'professional' stations to be wearing the Emperor’s New Clothes. All faux excitement and faux dialogue with listeners, but nary a raw emotion in sight … or sound.

[First published in 'The Radio Magazine', May 2004]

August 21, 2023

Give them a foot and they’ll take a metre : 1972 : Bill Beaver, Camberley & Alicante

It was the summer of rock’n’roll. Bill Haley. Buddy Holly. Chuck Berry. Fats Domino. The Big Bopper. Now, every time I hear one of their songs, I am reminded of a summer vacation never to be forgotten … for all the wrong reasons! Certainly, much of it had been spent lazing on a lounger beside a swimming pool, immersed in an interesting book I had brought along. However, my ears had been battered for days by continuous rock’n’roll, blasted at maximum volume from a tinny cassette machine leant against the wall of a Spanish villa’s veranda. This was not the preferred soundtrack of my teenage years.

At age fourteen, ‘oldies’ from a decade earlier already belonged to a bygone generation. I was obsessed with contemporary pop music and, since the occasion Jim Morrison had dropped his leather pants onstage, every Thursday a slice of my pocket money crossed the counter of a Frimley High Street newsagent for ‘Disc & Music Echo’, ‘Record Mirror’, ‘Sounds’, ‘NME’, ‘Melody Maker’ and ‘Blues & Soul’. I devoured their every word cover-to-cover, as well as teen magazine ‘Fab 208’ that my grandparents bought for older cousin Lynn but offered me a sneaked read. These publications’ preoccupation with the newest music (aligning perfectly with their most lucrative advertisers, the major record companies) reinforced my youthful music snobbery, as dismissive of rock’n’roll as I was of The Andrews Sisters.

Our family’s summer sojourn read like a rejected script for ‘Benidorm’. Following his impulsive visit to a Camberley travel agent to book a package holiday to Spain for the five of us, my father had handed me a pocket guide to Spanish, anticipating my fluency by the time we arrived. Although I shouldered the mantle of family administrator, this expectation proved unrealistic considering my recent struggle at school to learn French, where I had come bottom of the class during my first two years. As the teacher insisted on seating us in his classroom in rank order of our most recent termly exam result, I was placed in the front row due to my consistently dismal performances. By the time our charter flight touched down in Alicante, I had just about mastered Spanish numbers, greetings, shopping etiquette and the ordering of ‘steak and chips’.

Arrived at our hotel in the Albufereta district, the receptionist confessed that the promised restaurant and swimming pool were still ‘under construction’. Our two adjacent bedrooms on an upper floor lacked air conditioning and offered a view of only the hotel’s ongoing noisy building works. Daily pills my father took for high blood pressure had insufficient efficacy to stop him raising hell with the hotel’s management, to no avail, tipping his mood into a very un-holiday rage. To escape the confines of our half-finished accommodation, one hot afternoon we all trooped down to the beach, only for my months-old sister to put a handful of sand in her mouth. She cried, my mother panicked, my father shouted, screaming that he would never take his family to a beach again … a threat he kept.

After that incident, my father decided to hire a small Seat car so that we could explore Spain beyond the coast. One day he drove us inland to a random small village where we disembarked and wandered around in the heat of the blazing sun. It resembled a sand-blown ghost town from a television Western where everything was closed up, my parents having no knowledge of Spain’s daily siesta. The odd elderly person we encountered stopped what they were doing to stare pointedly at us, as if we resembled aliens arrived from another galaxy. They understood that only mad Brits and package holiday families came out in the midday sun. Feeling somewhat intimidated and having found nothing to do there, we retreated to the hire car to return to the ‘civilisation’ of our hotel.

My father tried to rescue our totally unedifying village visit by driving back along the picturesque Alicante seafront. Confronted by a small roundabout, he drove around it at his usual excessive speed in the wrong direction and collided with a car headed towards us. Nobody was hurt but the encounter caused visible damage to the front of both cars. The Spanish driver jumped out and understandably raged at my father, whose short fuse had been smouldering since the hour of our arrival. My translation skills were demanded, unrealistically as the pocket guide lacked a chapter on Spanish expletives. While the two drivers locked in verbal combat, the four of us sat on the low wall along the edge of the brightly tiled Alicante promenade. Passers-by stared. My baby sister was screaming. My mother was crying. The sun was baking us.

After a while, a police car arrived. My father was offered two choices. Either he could be arrested and taken to the police station to face a charge of dangerous driving, or he could pay the other driver to repair his car. While we remained sat on the promenade, my father accompanied a policeman to the nearest money exchange bureau to swap our remaining British ‘Travellers’ Cheques’ for Spanish pesetas. In the heat, it seemed like an eternity until he returned, paid the driver and we could all depart the scene of the crime. Our hire car was damaged but fortunately driveable, though there remained the problem of what to explain to the hire company at the end of our holiday from hell.

Our more immediate problem was how to survive the remainder of our fortnight now that almost all our money had been used to pay the angry driver. British credit cards might have launched in 1966 but had not been offered to families like ours. Debit cards would not exist until 1987. The limited amount of cash or Travellers’ Cheques you were permitted to take abroad had to be inscribed on the last page of your passport. Transferring funds from a British bank account to Spain, while you were in Spain, was an impossibility. During the following days, I escaped the worsening parental arguments at our hotel by finding a nearby newsagent where I would sit cross-legged on the floor for hours, looking through piles of imported DC comic titles never seen at home. I also found a record shop where I used pocket-money I had secreted to buy a Spanish 1971 James Brown picture-sleeve single (‘I Cried’) unreleased in the UK.

That summer’s rock’n’roll soundtrack was a consequence of my father’s solution to our predicament. While we would continue to sleep in our package holiday’s half-finished hotel, he had hustled an invitation to spend our remaining vacation daytimes at the nearby villa of one of his business associates. We lounged beside an Olympic-size outdoor swimming pool whose shallow end was bizarrely three times my height. The towering villa’s doorways were big enough to drive through a truck. Its rooms were the height of a church and the living room resembled a ballroom. We had traded our building-site hotel for a newly built mansion that could have easily served as a set for ‘Land of The Giants’ or the inspiration for a new ‘The Borrowers Abroad’ sequel.

The owner had purchased the plot of land, ordered a custom plan for a villa from an architect in Britain, brought the designs on paper to Spain and given them to local builders to construct during his absence. Returning only once it had been finished, he was astonished to realise that his plan’s dimensions in ‘feet’ had been misinterpreted as ‘metres’, resulting in the building and pool being three times their intended size. It was too late to remedy the error and too expensive to demolish it and rebuild. Planning regulations? What were they? The accidentally gigantic villa was there to stay … and we were now its guests.

It was the owner’s two sons, around a decade older than me, who had wired up a cassette machine outdoors to play their favoured rock’n’roll music. Though our three hosts hung around the villa and pool all day, they mostly ignored me quietly reading my book in the shade. Even the pool’s shallow end was too scary for a non-swimmer like me, however much they tried to persuade me to dive in. They were plainly enjoying their lazy, hazy days of summer on the ‘Costa del Dodgy’. I must have appeared quite a joyless nerd to them.

Our ebullient host Bill Beaver owned a successful car and truck dealership in Camberley, located on an expansive near-derelict triangle of land at the town’s western extreme. He lived in an old-style mansion named ‘Badgers’ Sett’ opposite ‘The Cricketers’ pub on Bracknell Road in nearby Bagshot. His accent was ‘Eastenders’ and his patter was pure Del Boy. My father had lately begun to forge local property redevelopment deals for which Beaver provided the cash, while he ensured local council planning approval for architectural schemes he drafted. My parents had uncharacteristically started hosting dinner parties for Beaver and his wife, despite my mother not warming to the couple’s brash ostentatiousness. My father probably hoped Beaver’s wealth would rub off on him … and, for a while, some of it did.

I had been pressganged into their joint enterprise to calculate the potential ‘return on investment’ of their projects, using my O-level maths studies to amortise the costs over varying numbers of years. One such development site was an anachronistic one-pump petrol station and car repair workshop that occupied a valuable rectangular plot on the busy London Road at Maultway North between Camberley and Bagshot. Owner John Sparks had inherited the business in 1966 upon the death of his father Arthur, though neither had updated its blue corrugated iron shack since 1926 when Arthur’s mother had purchased this large corner plot from the adjacent secondary school sportsground for her son to launch his one-man business.

Once I had calculated the viability of replacing the ramshackle building with flats, including the cost of removing the underground petrol tank and cleansing the polluted soil, the project was determined a ‘go’. However, we had not reckoned on Sparks’ stubborn refusal to sell. Beaver visited him. My father visited him. The Beaver sons visited him. Sparks remained intransigent. Their ‘persuasion’ techniques were evidently not working. Beaver purchased the Jolly Farmer pub on the roundabout opposite the Sparks site. One night it suffered a large unexplained fire. Sparks still refused to sell. In the end, the project had to be abandoned.

Like my mother, I was less in thrall of Beaver’s ‘entrepreneurship’ style than was my wide-eyed father, so the end of our disastrous two-week holiday in Spain and our farewells to his oversized villa came as a welcomed relief. On the flight home, I was seated next to larger-than-life Trinidadian bandleader Edmundo Ross. Despite already loving reggae and Brazilian music, my youthful snobbery regarded Ross as old-school due to his regularity on ‘BBC Radio 2’. Unaware of his fascinating life, I now regret not having chatted with him more.

A short time after our return to Britain, my father left us permanently to set up a new home with a teenage girl only a few years older than me. Our Spanish holiday seemed to have proven his last straw playing ‘happy families’. Children just got in his way. I had no further contact with the Beaver family … and I disowned my father.

In 1986, Tesco and Marks & Spencer jointly purchased a huge 76-acre site on the western fringe of Camberley to build two massive superstores (‘The Meadows’). The adjacent four-acre site, bounded by the London Road, Laundry Lane and Tank Road housed Bill Beaver’s open-air vehicle sales operation and was necessary to developers for a revised traffic flow system that included a new Sainsbury’s Homebase superstore. This plot on the far edge of town had suddenly become Camberley’s most valuable piece of land … to the benefit of its wily owner.

In 1990, John Sparks applied to Surrey Heath council for permission to build a bungalow (for his retirement?) on empty land at the back of his one-man garage. It was granted but never built. In 2014, seventy-eight-year-old Sparks retired, closed his business and sold the land to developer North Maultway Limited which demolished the workshop to build ten flats, for which planning permission was approved the following year. By 2017, the land had been sold to Seville Developments Limited which reapplied for planning permission to build nine flats. Two years later, this permission expired … leaving the former ‘Sparks Garage’ site derelict to this day.

August 12, 2023

One small step for radio, one giant leap for black music radio in London : 1990 : KISS 100 FM launch day

The final few days before KISS FM’s official launch were a blur of frenetic activity and outright panic. It was only at this late date that construction of the three studios was completed by the contractors. Now, at last, they were ready for the engineers from the Independent Broadcasting Authority [IBA] to test and inspect. Much to my relief, their report required only a few minor alterations to the air conditioning system, after which the IBA issued KISS FM with a certificate of technical competence. I affixed it to my office wall, alongside the poster of Betty Boo [I had pinned as my memento of DJ Tim Westwood’s ‘reason’ for reneging last-minute on his scheduled daily daytime show].

With only days to go, I held two long, evening meetings with all the part-time DJs to explain what they could and could not do legally on-air. As former pirate DJs, they were unfamiliar with the conventions of libel, slander and other legal niceties which legitimate radio DJs have to learn. It was important for me to emphasise how essential it was for KISS FM to protect itself against prosecution or rebuke by the commercial radio regulator, the IBA. I went through their employment contracts, page by page, explaining what the jargon meant and what implications the clauses had for their radio shows. Also, I had to stress the importance of playing the right advertisements at the right time. This was a contractual requirement that had been relatively relaxed on pirate stations.

The night before the station’s launch, I was still busy putting the finishing touches to the inside of the studio until the early hours of the morning. Although two on-air studios had been built, there was only time to bring one of them up to scratch with all the accessories required for live broadcasts. With only hours to go, the engineers and I were frantically drilling holes in the studio walls to hang the storage racks for audio cartridges used to play advertisements, as well as wiring up the studio lights on the ceiling. I handwrote several large posters in thick felt pen to remind the presenters of the station’s address, its phone number for requests, and what to say about the station’s launch. Then, I had to spend several hours making labels with a Dymo and sticking them onto each piece of equipment in the studio for the presenters to know precisely which button performed which task. Finally, when everything was ready, I drove home and collapsed into bed.

The next morning, Saturday 1 September 1990, was the biggest day of our lives. Some weeks earlier, [managing director] Gordon McNamee had hung a handwritten sign on his office wall that read “X DAYS TO GO” with the number being changed daily. That number was now down to zero and the sign had finally become redundant. The day had arrived at last, whether we were ready for it or not. McNamee and I met at the station in the morning and locked ourselves away inside the production studio. McNamee wanted to perform a countdown to the station’s launch at midday but, in order to ensure that it went perfectly smoothly, he wanted to pre-record it. I set the timer on my digital wristwatch to five minutes and recorded McNamee’s voice, counting down at one-minute intervals from five minutes to one minute, and then counting down the seconds during the final minute until the alarm sounded. It took two attempts to get it right.

After that, we moved to the main on-air studio, taking the tape of the countdown with us. We had decided not to allow anyone other than essential station personnel into the studio for the launch. It was not a big enough room to comfortably accommodate more than a few people, and the presence of journalists would only have made us even more nervous. McNamee had arranged for Mentorn Films, which was making the television documentary about the station, to erect a tripod camera in the corner of the studio to record the whole event. A video link had also been booked to relay the picture live to a large screen in Dingwalls nightclub, where the official KISS FM launch party was being held that day.

With all the tension that surrounded that historic day, we quickly forgot that we were being watched by a video camera from the corner of the room. I spooled McNamee’s countdown recording onto a tape machine and started it at precisely five minutes to midday. McNamee’s countdown was now automatically being superimposed over the music from the test transmission VHS cassette that had been playing continuously for the last ten days. Over the beats of the Kid Frost hip hop track ‘La Raza,’ McNamee’s voice coolly counted down the minutes. At the one-minute point, McNamee counted “59, 58, 57, 56....” and I slowly faded out the music to increase the suspense of the moment. Accompanied by the pre-recorded sound of my digital watch alarm, McNamee said the magic words “twelve o’clock.”

I turned up the microphone in the studio for McNamee to make KISS FM’s live opening speech:

“This is Gordon Mac. There are no words to express the way I feel at this moment. So, with your permission, I’d just like to get something out of my system. Altogether – we’re on air – hooray!”

Everyone in the studio joined in a loud cheer, before McNamee continued:

“Welcome, London. Do you realise it’s taken us fifty-nine months, four hundred and sixty-five thousand, seven hundred and twenty working hours, plus three and a half million pounds, as well as all of your support over the last five years, to reach this moment? As from today, London and everywhere around the M25, within and without, will have their own twenty-four-hour dance music radio station. I’m talking to you from our new studios in KISS House, which is completely different from the dodgy old studios we used to have in the past [laughter in the studio]. The odds were against us. None of the establishment fancied our chances but, with the force of public opinion and our determination, the authorities had to sit up and listen and take notice. Today, I’m being helped by Rufaro Hove, the winner of ‘The Evening Standard’ KISS 100 FM competition. Rufaro was chosen from thousands of people who entered and she will press the button for the first record. But before that, the first jingle.”

McNamee pushed the cartridge button to play a lo-fi jingle from KISS FM’s pirate days. The sound of a telephone answering machine tone was followed by McNamee’s personal assistant, Rosee Laurence, saying:

“It’s me again. I forgot to say – hooray, we’re on. Bye-bye.”

The jingle ended with the sound of a phone being put down. McNamee continued:

“There we go, Rufaro, now you can press the first one. Go!”

The first record played on the new KISS FM was the reggae song ‘Pirates’ Anthem’ by Home T, Cocoa Tea & Shabba Ranks. The song was a tribute to London’s pirate radio stations. The rallying call of the chorus was:

One of the song’s verses narrated the story of pirate radio in the UK:

“Them a call us pirates

Them a call us illegal broadcasters

Just because we play what the people want

DTI tries [to] stop us, but they can’t"

"Down in England we’ve got lots of radio stations

Playing the peoples’ music night and day

Reggae, calypso, hip hop or disco

The latest sound today is what we play........

They’re passing laws. They’re planning legislation

Trying their best to keep the music down

DTI, why don’t you leave us alone?

We only play the music others want”

These lyrics were the perfect choice for the station’s first record. KISS FM’s pirate history may have been behind it now, but the station had proven that pirate broadcasting had been necessary to open up the British airwaves to new musical sounds and fresh ideas for the 1990s. ‘Pirates’ Anthem’ was followed by the personal choice of the Evening Standard competition winner, ‘Facts of Life’ by Danny Madden. In the studio, the atmosphere was electric. It was difficult to believe that the few of us crowded into that little room were making broadcasting history. This was the creation of the dream that some of us thought we might never witness – a legal black music radio station in London, at last. It was difficult to believe we were really on the air.

Next, McNamee thanked “all the original disc jockeys, all the backers, all the new staff and last, but not by any means least, all of the listeners that have supported us over the five years.”

He introduced the record that he had adopted as KISS FM’s theme tune – ‘Our Day Will Come’ by Fontella Bass. The station’s first advertisement followed, booked by the Rhythm King record label to publicise its latest releases. Soon, McNamee’s stint as the station’s first DJ came to an end and his place was taken by Norman Jay, whose croaky voice betrayed the emotion of the day. Jay told listeners over his instrumental ‘Windy City’ theme tune:

“After nearly two very long years, all the good times, all the bad times we shared on radio ... Thanks to all of you. Without your help, this day could not have been possible. On a cold and wet October day in 1985, KISS FM was born. Gordon Mac, George Power and a long-time friend of mine, Tosca, got together to put together a station which meant so much to so many. And thanks to those guys, Norman Jay is now on-air.”

Once Jay was on the air, McNamee said farewell to the rest of us in the studio and left to attend the station’s official launch party at Dingwalls. We stayed in the studio, still thrilled to be part of the celebration of that historic moment and enjoying the music that Jay played. Throughout the rest of the weekend, each KISS FM DJ presented their first show on the newly legal station. Many of them reminisced about the pirate days of KISS FM and played music from that era, when they had last graced the airwaves of London. To the majority of the station’s audience, who might never have heard of KISS FM until now, the weekend’s broadcasts must have sounded rather indulgent. Far from most of the records played that weekend reflecting the cutting edge of new dance music that the new KISS FM had promised, the songs mostly reeked of nostalgia and the station’s former glory days as a pirate station. This brief moment of indulgence was a healing process that was necessary for the station’s staff.

I remained in the studio the rest of the day, helping the DJs to grapple with the unfamiliar equipment and showing them the new systems with which they had to contend. Despite the intensive training they had been given in the last ten days, it had been twenty months since any of them had spoken a word on the radio, let alone presented a professional show. Nearly all the DJs looked incredibly nervous, and several seemed gripped with terror at the prospect of having to present a show from a fully equipped radio studio for the first time in their lives. I stayed there until the early hours of Sunday morning, with only an occasional break for a takeaway pizza.